Abstract

Study Design:

Resident's Case Study

Background/Introduction:

The reports of spinal accessory nerve injury in the literature primarily focus on injury following surgical dissection or traumatic stretch injury. There is limited literature describing the presentation and diagnosis of this injury with an unknown cause. The purpose of this case report is to describe the clinical decision-making process that guided the diagnosis and treatment of a complex patient with spinal accessory nerve palsy (SANP) whose clinical presentation and response to therapy were inconsistent with the results of multiple diagnostic tests.

Case Description:

The patient was a 27-year-old female triathlete with a five month history of right-sided neck, anterior shoulder, and chest pain.

Outcome:

Based on the physical exam, magnetic resonance imaging, radiographs, electrodiagnostic and nerve conduction testing, the patient was diagnosed by her physician with right sterno-clavicular joint strain and scapular dyskinesis and was referred to physical therapy. Care was initiated based on this initial diagnosis. Upon further examination and perusal of the literature, the physical therapist proposed a diagnosis of spinal accessory nerve injury. Intervention included manual release of soft tissue tightness, neuromuscular facilitation and sport-specific strengthening, resulting in full return to functional and sport activities. These interventions focused on neurological re-education and muscular facilitation to address SANP as opposed to a joint sprain and dysfunction, as initially diagnosed.

Discussion:

Proper diagnosis is imperative to effective treatment in all patients. This case illustrates the importance of a thorough examination and consideration of multiple diagnostic findings, particularly when EMG/NCV tests were negative, the cause was not apparent, and symptoms were less severe than other cases documented in the literature.

Level of Evidence:

Diagnosis, level 4

Keywords: Differential diagnosis, shoulder pain, spinal accessory nerve palsy, sterno-clavicular pain, triathlete

INTRODUCTION

Patients with peripheral nervous system injuries are commonly treated by physical therapists. A peripheral nerve injury is an injury to the nerve root or more peripheral area of a nerve. The presentation of a peripheral nerve injury may include motor loss in muscles innervated by the injured nerve, with or without sensory deficits. The etiology of peripheral nerve injuries includes traumatic events, most often from motor vehicle accidents, lacerations, stretch or compression, and iatrogenic factors.1

The spinal accessory nerve (SAN) is a peripheral nerve that can sustain injury by a traumatic blow, a severe stretch/traction, or laceration during surgery.2–4 The SAN is particularly vulnerable to injury because of its subcutaneous location3,5 as it courses through the posterior triangle of the cervical region which is bordered by the middle third of the clavicle, posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM), and the anterior portion of the upper trapezius.6 The SAN provides motor but not sensory innervation to the SCM and trapezius muscles.2,3 When there is an injury to the SAN, the clinical presentation is labeled spinal accessory nerve palsy (SANP). The presentation of SANP includes shoulder depression, scapular dyskinesis, and dysfunctional movement patterns of the neck and shoulder region caused by decreased strength of the ipsilateral upper, middle, and lower trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles.2,3,7,8

When an upper extremity peripheral nerve injury is suspected, diagnostic testing is frequently used to confirm if nerve impairment is present. Radiographs are often the first diagnostic test used to assess the cervical spine. Radiographic images are used to assess the cervical spine and shoulder complex for bony abnormalities that may contribute to peripheral nerve impairments, but are not appropriate for examining tissue other than bone. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) provides a high level of soft tissue differentiation; however, these images do not assess the functional status of a peripheral nerve so other additional studies are beneficial to completely diagnose nerve pathology.9 Electrodiagnostic studies are more useful for assessing neural pathology than imaging studies. Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) and needle electromyography (EMG) offer valuable information to the clinician regarding muscle innervation, the ability of a specific nerve to transmit neural activity, and the location of a nerve injury. When an injured nerve is tested over time, the tests may provide information regarding muscle re-innervation.10 Electrodiagnostic tests are recommended as the best tools to differentiate radiculopathy from a musculotendinous shoulder injury.9 Differentiating the tissue involved in the pathology can help the clinician in making a differential diagnosis and choosing appropriate interventions. Unfortunately, despite suggestions to use EMG and NCV to detect a SANP,6–8 authors describing the presentation and findings of SANP have reported inconsistent results of electrodiagnostic tests when assessing spinal accessory nerve palsy.2,11 The sensitivity and specificity of electrodiagnostic tests for detecting SANP specifically could not be found in the literature.

The ability to differentiate peripheral nerve injuries from local musculoskeletal injuries is imperative to optimize patient outcomes. The performance of a thorough examination and development of a differential diagnosis list, instead of relying on previous examinations and testing, is what supports the physical therapists ability to facilitate individualized treatment effectively. Since an injury to the SAN involves motor loss without sensory dysfunction, it is often difficult to clinically differentiate SANP from a musculoskeletal dysfunction. A false negative encountered in diagnostic testing makes proper diagnosis even more difficult. In addition, the reports of spinal accessory nerve injury in the literature primarily focus on injury following surgical dissection or traumatic stretch injury. There is limited literature describing the presentation and diagnosis of this injury with an unknown cause. However, by developing a comprehensive list of differential diagnoses and continually assessing patient presentation and response to interventions, physical therapists are ideally suited to make evaluative judgements that can lead to the proper physical therapy diagnosis and treatment of complex patients. Therefore, the purpose of this case report is to describe the clinical decision making process that guided the diagnosis and treatment of a complex patient with SANP whose clinical presentation and response to therapy were inconsistent with the results of multiple diagnostic tests.

CASE DESCRIPTION

The patient was a 27-year-old, left-handed, female nurse and avid triathlete. She had a five month history of right shoulder and anterior chest pain with associated decreased functional ability, including sport participation. The only significant past medical event was a lumbar compression fracture that occurred due to falling from a horse 10 years prior. The patient reported no continued symptoms from the lumbar fracture.

The patient described first noticing her symptoms 3 days after participating in a ninjitsu martial arts class. The symptoms included achy, muscular pain over the right side of her neck and superior aspect of her shoulder and sharp pain over her right anterior chest with movement. She could not remember a specific mechanism of injury but did report that she felt as though she strained her right shoulder and neck during the class. Despite her symptoms, she continued to train for upcoming triathlon competitions with a strenuous training plan, including at least one training session daily, which exacerbated her anterior chest and shoulder pain.

Due to the effect of pain and dysfunction on her training, the patient consulted with her primary care physician one month after the onset of her symptoms. Radiographs and a MRI were performed on her right shoulder within a week of this visit and were determined to be normal. However, the information gained from the MRI may have been limited since it did not image the cervical spine region which also is a potential source of shoulder complex symptoms. Her physician recommended that she cease activities that increased her pain and continue to self-monitor her symptoms. The patient was only partially compliant with this advice as she tried to maintain her training at a level as high as possible without pain.

Over the subsequent 2 months, the patient noted progressively increasing pain with work and training activities, increased asymmetry of her shoulder including depression of the shoulder and increased appearance of bony prominences, and further decline in her ability to train, most notably during swimming and resistance training. Therefore, she returned to her physician for a follow-up examination. After this visit, NCV and EMG studies were performed on her right cervical paraspinal muscles, serratus anterior, levator scapulae, and upper trapezius, from which normal findings were reported. The patient was then referred to a physician, an orthopedic specialist, for a second opinion. Radiographs and a MRI of the right shoulder were repeated and again reported as normal. She was diagnosed with scapular dyskinesis and a right sternoclavicular (SC) joint strain by the physician. Treatment included a local steroid/anesthetic injection to the sternoclavicular joint, which provided mild relief of her pain. Five months following initial onset of symptoms, the patient was referred to physical therapy (Figure 1).

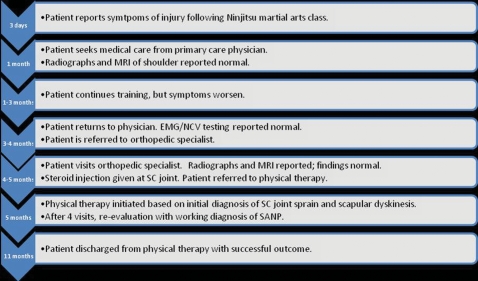

Figure 1.

Timeline of Events.

Examination

During the initial physical therapy examination, the patient complained of sharp anterior chest pain with lifting weights, reaching overhead, and performing push-ups or pull-ups. Pain with these activities was rated verbally at 7 on a 0 to 10 Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS); 10 being the worst pain possible. The NPRS has a moderate to high test-retest reliability (0.67 to 0.96) and responsiveness. A 3 point change is needed to demonstrate true change in pain.12 Her training included swimming, and she also was greatly limited in the ability to lift her head out of the water to breathe, suggesting a deficit in combined cervical motions of extension, rotation and sidebending. Dull, achy right anterior shoulder and right-sided neck pain (rated at 0 to 4 or 5 out of 10 on the NPRS) was noted at rest. The location of her symptoms can be viewed in her initial pain drawing in Figure 2. The patient denied any sensory disturbance including numbness or tingling in the neck, shoulder, or upper extremity. She reported taking over-the-counter Ibuprofen for pain as necessary. The patient's goals were to regain her range of motion in her shoulder and neck and to be able to participate in daily and sport activities without pain.

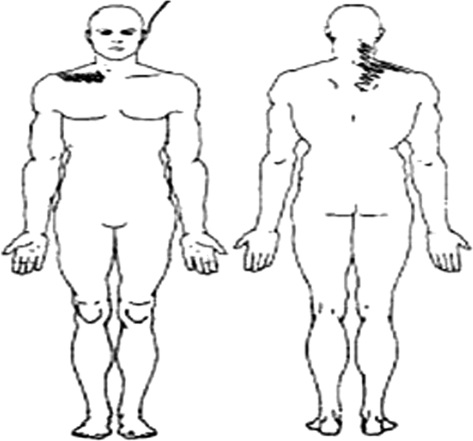

Figure 2.

Initial Symptom Drawing.

The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire (DASH), is an upper-extremity-specific health-related, quality of life functional outcome measure. It is a point-based, subjective questionnaire filled out by the patient that addresses each of the three areas of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model disease-based outcomes.13 It is used to assess difficulty in physical activities including upper extremity function, pain, weakness, stiffness, tingling, and impact on social and psychological health. The percent of disability is calculated with 0% reporting no dysfunction and 100% reporting maximal dysfunction. The DASH has been reported to have good test-retest reliability, validity, and responsiveness for the entire upper extremity.14 The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the DASH is approximately 10 points.15 The patient filled out the DASH questionnaire at her initial examination and during the progress in rehabilitation. Upon initial examination, the patient scored 21.7% functional disability and 100% disability in sport on the DASH.

Upon observation, the patient's gait appeared normal, and she demonstrated normal arm swing of her involved upper extremity during ambulation. Her posture was moderately impaired with a moderate forward head, forward shoulder positioning (right greater than left), and a decreased thoracic kyphosis. Her right shoulder was visually estimated to be depressed approximately 1.5 inches compared to the left shoulder. The right clavicle was in a position of anterior protrusion, with the sternal end superiorly positioned and the acromial end inferior to the left clavicle. According to definitions by Sahrmann,16 the right shoulder girdle was depressed and forward, and the scapula was downwardly rotated. There was moderate atrophy of her right upper trapezius muscle (Figures 3 and 4) and the right SCM.

Figure 3.

Patient Presentation Upon Initial Examination. Note right scapular position and muscular atrophy of Upper trapezius and Sternocleidomastoid.

Figure 4.

Patient Presentation: Posterior. Note right scapular position and muscular atrophy.

Palpation of the right sternoclavicular joint induced significant, sharp, localized pain. Muscular palpation included symptoms of tenderness throughout the right upper trapezius, decreased tissue mobility in bilateral suboccipital musculature, and bilateral cervical paraspinals. Although there was muscular tenderness, concordant signs and symptoms were not reproduced.

Movement testing revealed scapular dyskinesis, notably decreased control of the right scapula on eccentric lowering of the right upper extremity from elevated positions of flexion and abduction. This movement pattern is consistent with a Type III Kibler classification, allowing for superior-medial prominence of the scapular border.17 At that time, there was no distinction made regarding the severity of the symptoms in flexion as compared to abduction motions, as dyskinetic movement was observed in both planes of movement. However, diagnosis is difficult using visual observation of the shoulder complex as a study previously demonstrated physical therapists correctly identifying shoulder movement classification only 57.5% of the time.18

The patient's active range of motion was measured using a standard goniometer (Table 1). Active range of motion was limited for cervical sidebending to the right and rotation to the left, and for right shoulder complex flexion and abduction. Cervical rotation to the right was 70 degrees and 55 degrees to the left with compensatory movements of cervical sidebending and thoracic rotation to attempt full motion. Shoulder complex flexion was 180 degrees on the left and 150 degrees on the right. Active abduction of the shoulder complex was 190 degrees on the left and 150 degrees on the right. Active shoulder flexion and abduction elicited pain at the right sterno-clavicular joint. However, pain was not the active range limiting factor. Lack of strength limited the patient's active range of motion. Right shoulder complex passive ROM was equal to that of the left.

Table 1.

Range of Motion, Initial Examination

| Motion | Left | Right |

|---|---|---|

| Active Cervical Rotation | 55° | 70° |

| Active Shoulder Flexion | 180° | 150° with pain |

| Active Shoulder Abduction | 190° | 150° with pain |

| Passive Shoulder Internal Rotation | 55° | 55° |

| Passive Shoulder External Rotation | 100° | 95° |

The upper quarter neurological examination revealed normal sensation to light touch throughout the upper extremities and upper quadrants and normal biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis reflexes. The general upper limb tension test (ULTT) and compression/distraction were both negative. Strength testing revealed notable weakness on the right (Table 2). Strength grades included 4/5 in right cervical sidebending, 4/5 in cervical rotation to the left, 4+/5 in cervical rotation to the right, 4/5 in right shoulder flexion and abduction. The right upper trapezius strength was 2+/5, right middle and lower trapezius were each 3+/5; while all three portions of the trapezius were 4/5 on the left.

Table 2.

Manual Muscle Testing Findings, Initial Examination

| Muscle or Action Tested | Left | Right |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical side-bending | 5/5 | 4/5 |

| Cervical rotation | 4/5 | 4+/5 |

| Gross Shoulder Testing: flexion, abduction | 5/5 | 4/5, pain at sternoclavicular joint |

| Upper Trapezius | 4/5 | 3+/5 |

| Middle Trapezius | 4/5 | 3+/5 |

| Lower Trapezius | 4/5 | 2+/5 |

Passive joint mobility testing19 revealed decreased mobility in the posterior direction for the patient's right glenohumeral and sternoclavicular joints. With spinal segmental mobility testing,19 the patient presented with decreased right sidebending and left lateral glides at the levels of C2-C6 and decreased joint play in the posterior-to-anterior directions throughout the thoracic segmental levels, when assessed using spring testing. The occipital-atlantal joint was also decreased in passive segmental flexion mobility.

The Hawkins-Kennedy impingement test, Empty Can resistance test, and Drop Arm test were administered to assess supraspinatus pathology. The apprehension test was used to rule out instability, while the Apprehension test, O'Brien's, Speeds test were used to assist in identifying labral or acromioclavicular joint involvement. None of these tests were positive for their intended purpose, but all elicited pain at the SC joint.

Assessment

Significant physical therapy findings included anterior chest and SC joint pain upon palpation and with active movement. The patient demonstrated decreased shoulder complex active range of motion, scapular dyskinesis with elevation, atrophy of the right upper trapezius and sternocleidomastoid, and weakness of the cervical, glenohumeral joint, and scapular musculature. Cervical, glenohumeral, and sternoclavicular joint mobility was decreased and there was decreased muscle activation present in the upper trapezius, while the cervical paraspinals had increased tension. Functional activity limitations included a limitation of her occupational tasks and triathlon training requirements. Electrodiagnostic studies performed on this patient were reported to be negative for nerve involvement, and general upper extremity nerve tension testing was negative. Thus, the initial plan of care was developed to limit the dysfunctional movement of the SC joint and to increase mobility in the posterior direction where mobility was limited in order to decrease pain, improve cervical and glenohumeral active range of motion, and increase strength in the weak cervical and right upper extremity musculature, all to increase patient function.

During the first 4 treatment sessions, intervention included the following: ultrasound to assist with increasing posterior SC joint mobility; manual mobilizations to increase posterior SC joint mobility; posteriorly-directed taping to the SC joint to assist with normalizing arthrokinematic movement of the SC joint; and right shoulder complex strengthening exercises directed at the right scapulo-thoracic and right upper extremity musculature to improve functional reaching and lifting. During this initial treatment plan, outcomes were only mildly successful and the therapist surmised that the extent of the impairments suggested more than a SC joint sprain with scapular dyskinesis. The anterior neck pain and prominent SC joint on the affected side in this patient were consistent with SC joint sprain or subluxation.20 Palpation of the SC joint caused localized pain. Similarly, the pain at the SC joint was reproduced with all shoulder special tests, consistent with primary SC pathology. However, the therapist questioned the potential causes of the muscle atrophy and scapular dyskinesis. Hence, a working list of additional differential diagnoses was generated. This list included long thoracic nerve injury, cervical disc disease with radiculopathy, brachial plexitis, and spinal accessory nerve palsy. Subsequently, the possibility of each of these differential diagnoses in this patient was more thoroughly evaluated.

Patients with cervical disc disease with radiculopathy and brachial plexitis usually report pain in the cervical spine, as well as motor and sensory deficits in the upper extremity.21,22 The patient had no sensory deficits and a negative ULLT. The ULTT has a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 22%,23 therefore, it is an appropriate test to rule out cervical radiculopathy when negative.

Both long thoracic nerve injury and SANP may be caused by a stretch injury to the neck, traumatic blow to the neck, or by iatrogenic factors.2,3,5,6,8 However, due to the difference in neural innervation, these two pathologies present with differences in patient symptoms and impairments. The long thoracic nerve innervates the serratus anterior and the SAN innervates the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles. Key findings with a long thoracic nerve injury include glenohumeral instability, true scapular winging, and pain in the neck, shoulder, and peri-scapular regions.2,5 Additional findings of long thoracic nerve injury include weakness with overhead activities, difficulty with elevation in the frontal plane, and scapular instability with flexion as the serratus anterior fails to stabilize the medial border of the scapula on the thorax.5 In SANP, a constant ache across the shoulder is often noted,7 and downward rotation of the shoulder complex occurs secondary to the remaining tension of the levator scapulae and rhomboids with a lack of opposition of the trapezius.3,7,8 In a complete SAN injury, abduction often is limited to 90° secondary to lack of scapular stabilization and decreased ability to upwardly rotate the scapulae with the upper trapezius.6,8 Scapular dyskinesis occurs in abduction in SANP rather than flexion due to weakness in the middle and lower trapezius muscles.2,7,8

The use of EMG and NCV are reported to be helpful in differentiating between SANP and a long thoracic nerve injury;5–8 however, it appears there are inconsistent EMG/NCV findings in patients with SANP.2,11 Therefore, even with the negative electrodiagnostic findings, the therapist suspected the possibility of a long thoracic and/or SAN involvement at the spinal level in addition to a SC joint sprain. This may have initially been caused by a mild traction injury in martial arts, followed by entrapment due to the reflexive tightness of the surrounding musculature. Important findings included scapular and cervical spine weakness, visual presentation of atrophied trapezius and SCM, and scapular dyskinesis. However, to differentiate between long thoracic nerve palsy and SANP, further examination and special tests were deemed necessary.

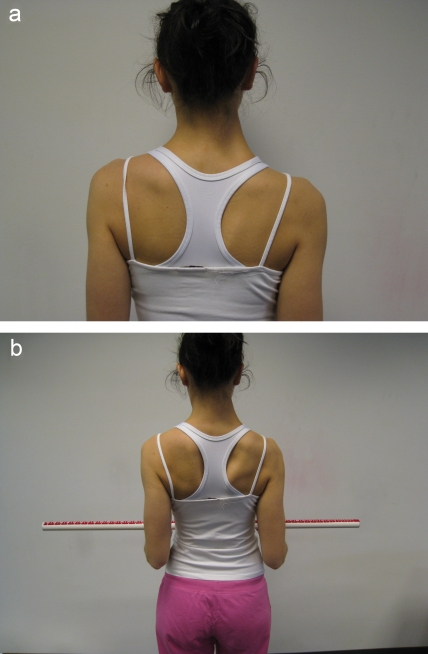

The Scapular Flip Sign is a clinical special test proposed to diagnose SAN pathology.24 This test is performed with the patient holding both arms at their side with elbows flexed to 90 degrees, holding a dowel rod in both hands, and externally rotating both shoulders against resistance. The test is considered positive when the lower and middle trapezii are unable to oppose the pull of the infraspinatus and posterior deltoid, causing the medial scapula to “flip” off of the thoracic wall. This test is different from the Push Up Test for serratus anterior weakness in that the positive Scapular Flip Sign is demonstrating a lack of middle and lower trapezius stabilization, and the Push Up Test demonstrates a lack of serratus anterior stabilization of the scapulothoracic joint.25 The Scapular Flip Sign has not been evaluated for specificity or sensitivity; however, in a case series of patients with SANP, the Scapular Flip Sign was positive in all 20 patients.2 This test, although not specifically named is similarly described by Chan.3 The current patient demonstrated a positive Scapular Flip Sign on the affected extremity, as shown in Figures 5a and 5b.

Figure 5.

a. Scapular Flip Sign: Start Position. b. Scapular Flip Sign: End Position.

Further examination revealed SCM weakness on the right (2+/5 on the right versus 4+/5 on the left). A closer look at the pattern of scapular dyskinesis revealed greater deficits in abduction as compared to flexion. With obvious muscle wasting of the trapezii and SCM, SC joint pain, anterior shoulder pain, shoulder drooping, a positive Scapular Flip Sign, and significant scapular dyskinesis primarily observed during abduction motions, spinal accessory nerve palsy with a secondary sternoclavicular joint sprain emerged as the likely diagnosis. However, it is probable that the injury was incomplete as the patient had partial muscle function of the right SCM and trapezius and right shoulder abduction was greater than 90°.

Intervention and Outcomes

If the SAN is injured iatrogenically or by a penetrating trauma, operative treatment is recommended. Conservative treatment is recommended for patients sustaining a SANP due to a traction injury5,7 or for those whose injuries are incomplete.6 Thus, conservative treatment was continued for this patient following reassessment. The physician was contacted at this point of re-examination, and was in agreement with the findings and treatment plan. For a patient who meets the criteria for conservative treatment, the prognosis for a patient to return to prior levels of functioning with manual nerve entrapment release, muscle re-education, and functional training is normally 4 to 6 months.2 This patient was initially examined in physical therapy approximately five months after the injury, but without treatment, she had not improved. The patient's presentation included a decreased ability to perform activities of daily living and decreased functional ability.

The initial physical therapy interventions included manual posterior mobilizations of the SC joint, tissue mobilizations to increase occipital-atlantal and cervical segmental mobility, and stabilization techniques to the SC joint to assist with normalizing right upper extremity movement and activities of daily living. After hypothesizing SANP as a possible working diagnosis, interventions were focused on improving soft tissue mobility of the muscles surrounding the posterior cervical triangle to release potential SAN entrapment, neuromuscular facilitation of the atrophied musculature, and strengthening of the muscles that allow for elevation and rotation of the right upper extremity. The goals of this treatment were to normalize dysfunctional postures and movements and to release the areas of possible SAN entrapment as it crosses the posterior triangle.

To increase the patient's ability to perform work and training activities, strengthening of the muscles that assist with performance of the limited movement patterns were initially taught and reinforced as, based on other studies, strength gains are thought to occur over 4-6 months.2 Strength training was used to maximize the use of the muscles surrounding the injury that would allow for the patient to perform her functional activities without significant pain or disability. The targeted muscles included the rotator cuff, deltoids, and serratus anterior to assist with glenohumeral elevation and upward rotation of the scapula for functional activities. The deep cervical stabilizing musculature and flexors also were trained to assist with head movements and assist the SCM in order to initiate cervical flexion and rotation.

Throughout the course of physical therapy intervention, neuromuscular retraining of the trapezius and SCM was necessary to initiate recruitment of these muscles secondary to the belief of diminished neural supply. Manual tapping and positioning of the patient's head was used to facilitate muscle activation. Once palpable muscular activation was evident with these techniques, facilitation was performed in more functional positions to mimic sport specific demands.

The patient attended her final physical therapy appointment approximately 6 months after the initial PT examination and approximately 11 months after injury. At that time, she had regained full active range of motion in her neck and shoulder, full strength in her cervical spine and right upper extremity, and returned to recreational and work activities without pain. The right scapulothoracic musculature, including right middle and lower trapezius, improved to 3+/5 with manual muscle testing. She was able to perform all weight lifting activities including bench press and overhead press, and ran the Pittsburgh Marathon in a personal record time, both without pain by May 2009, five months after the initiation of physical therapy. She was able to swim freestyle for 2 laps straight and able to perform 10, non-modified push-ups in a row. The patient also noted that she was now able to examine her backside in a mirror from both directions due to her gain in neck strength and mobility.

The DASH functional outcome measure at physical therapy termination revealed 9.2% functional disability and 31.25% sport disability, compared to her initial scores of 21.67% and 100%, respectively. Each of the changes in score exceeded the MCID for positive changes in functional outcomes on the DASH.15 All special tests were negative, except for the scapular flip sign, which remained positive at discharge.

DISCUSSION

Before a clinician can make a “physical therapy” diagnosis, a thorough examination and thoughtful evaluation is necessary. The Guide to PT Practice refers to the evaluation as a dynamic process.26 The clinician must thoughtfully consider all examination data and as re-evaluation occurs, initial decisions may be reconsidered, change, and/or evolve. To facilitate this process, a differential diagnosis list must be incorporated into the initial evaluation phase. Many pathologies appear similar and without examining all the possibilities, less obvious or less common diagnoses may be missed. This case problem illustrates both the importance of a careful differential diagnosis and constant re-evaluation using examination data.

The patient in this case came to physical therapy with a specific medical diagnosis of right SC joint sprain and a movement dysfunction diagnosis: scapular dyskinesis of non-specific etiology. The shoulder complex dysfunction and pain exhibited by this patient could have been caused by numerous pathologies making a thorough examination imperative. Upon reassessment, the initial differential diagnosis list included long thoracic nerve injury, SC joint strain, cervical disc disease with radiculopathy, brachial plexitis, and SANP. It is important to note that although the EMG and NCV findings were negative, a neurologic origin for this patient's impairments could not be definitively excluded. EMG and NCV findings should be considered along with physical examination to provide a diagnosis and are not independently diagnostic.10

After careful consideration and re-examination, the working diagnosis of sternoclavicular joint sprain and long thoracic and/or SAN involvement was made. In an attempt to clarify the pathology, the therapist consulted with co-workers and searched the literature. At first glance, SANP and long thoracic nerve injuries can appear quite similar due to the involvement of the scapula. However, injury to the long thoracic nerve involves dysfunction of the serratus anterior muscle while injury to the SAN involves dysfunction of the trapezius and the SCM. An important distinguishing detail to this diagnosis is that in a long thoracic nerve injury, true scapular winging occurs primarily when the upper extremity is elevated in the sagittal plane (flexion), while in SANP the prominence of the medial scapular boarder occurs primarily when the upper extremity is elevated in the frontal plane (abduction). In this patient, the scapular dysfunction was most prominent during arm abduction. This distinction helped differentiate between the diagnosis of SANP and a long thoracic nerve injury. However, as previously described, diagnosis is difficult using visual observation of the shoulder complex.18

Kelley et al2 reported that identifying SANP can be difficult and, therefore, proposed the use of the Scapular Flip Test. This positive test, combined with the scapular dyskinesis observed during active range of motion, muscular atrophy, and drooping of the shoulder, led the therapist toward SANP as the final diagnosis.

It is unknown why the EMG and NCV testing was not positive for nerve injury in this case. The testing was performed approximately four months after the injury occurred (greater than the proposed 21 days for EMG/NCV testing).10 It is possible that operator error may have played a role, and the needle may have passed through the upper trapezius to an innervated supraspinatus muscle.2 Other cases described in the literature have reported negative nerve conduction test findings in patients with the diagnosis of SANP, as was the presentation in the current case.2,11

A proper diagnosis guides treatment for optimal outcomes. In this case, once the SANP diagnosis was considered most likely, the treatment plan was modified and became more specific to address issues related to the nerve involvement. With partial function of the trapezius and SCM remaining, it is likely the palsy was incomplete. Therefore, treatment emphasized manual soft tissue treatment of involved muscules and mobilization of bony structures that could be creating tension or pressure on the nerve. Also important was facilitating activation of the affected musculature, and strengthening the surrounding musculature until the trapezii and SCM regained function. Based on the successful outcome of this patient, it appears that the differential diagnosis process was helpful in determining an appropriate diagnosis and effective treatment plan.

CONCLUSION

SANP is a rare and potentially easily missed diagnosis. This case illustrates the importance of a thorough examination and considering multiple diagnostic findings, particularly when EMG/NCV tests were negative, the cause was not apparent, and symptoms were less severe than other cases documented in the literature. Although it appears the process used in this case was beneficial to guiding treatment, it cannot be generalized to all patients. It is feasible that the interventions may have been successful based on the signs and symptoms regardless of the identification of SANP. Also, it cannot be determined which of the interventions was most successful or if there was natural healing that occurred due to the passage of time. Further research is needed to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of the Scapular Flip Test; as well as to examine the same parameters for electrodiagnostics when used for identifying SANP. Conservative interventions for SANP also need to be assessed for their effectiveness.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eser F, Aktekin LA, Bodur H, Atan C. Etiological factors of traumatic peripheral nerve injuries. Neurol India. 2009;57(4):434–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kelley MJ. Spinal accessory nerve palsy: associated signs and symptoms. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(2):78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan PK, Hems TE. Clinical signs of accessory nerve palsy. J Trauma. 2006;60(5):1142–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Toth C, McNeil S, Feasby T. Peripheral nervous system injuries in sport and recreation: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2005;35(8):717–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Safran MR. Nerve injury about the shoulder in athletes, part 2: long thoracic nerve, spinal accessory nerve, burners/stingers, thoracic outlet syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):1063–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berry H, MacDonald EA, Mrazek AC. Accessory nerve palsy: a review of 23 cases. Can J Neurol Sci. 1991;18(3):337–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wiater JM, Bigliani LU. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(368)(368):5–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Akgun K. Conservative treatment for late-diagnosed spinal accessory nerve injury. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2008;87(12):1015–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Polston DW. Cervical radiculopathy. Neurol Clin. 2007;25(2):373–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Echternach J. Introduction to electromyograph and nerve conduction testing. 2nd ed. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bigliani LU, Perez-Sanz JR, Wolfe IN. Treatment of trapezius paralysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:871–877 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kahl C, Cleland JA. Visual analogue scale, numeric pain rating scale and the McGill Pain Questionnaire: an overview of psychometric properties. Phys Ther Rev. 2005;10(2):123–128 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dixon D, Johnston M, McQueen M, Court-Brown C. The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire (DASH) can measure the impairment, activity limitations and participation restriction constructs from the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:114–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beaton DE. Measuring the whole or the parts? Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Outcome Measure in different regions of the upper extremity. J Hand Ther. 2001;14(2):128–146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jean-Sebastien R, MacDermid J, Woodhouse L. Measuring shoulder function: a systematic review of 4 questionnaires. Arthr Care Res. 2009;61(5):623–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sahrmann S. Diagnosis and treatment of movement impairment syndromes. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kibler WB, McMullen J. Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(2):142–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hickey BW. Accuracy and reliability of observational motion analysis in identifying shoulder symptoms. Man Ther. 2007;12(3):263–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaltenborn F, Evjenth O, Kaltenborn T, Morgan D, Vollowitz D. Manual Mobilization of the Joints;, Volume II: The Spine, 4th edition. Minneapolis, Minnesota: OPTP; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Echlin PS, Michaelson JE. Adolescent butterfly swimmer with bilateral subluxing sternoclavicular joints. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(4):4p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Korinth MC. Treatment of cervical degenerative disc disease - current status and trends. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2008;69(3):113–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wendling D. Parsonage-Turner syndrome revealing Lyme borreliosis. Joint, bone, spine : revue du rhumatisme. 2009;76(2):202–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wainner RS, Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ, Boninger ML, Delitto A, Allison S. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination and patient self-report measures for cervical radiculopathy. Spine. 2003;28(1):52–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kelley MJ, Brenneman S. The scapular flip sign: an examination sign to identify the presence of a spinal accessory nerve palsy. APTA Combined Section Meeting. New Orleans, LA. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dutton M. Orthopaedic examination, evaluation, and intervention. New York: Mc-Graw-Hill; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, 2nd Edition Alexandria, Virginia: American Physical Therapy Association; 2003 [Google Scholar]