Abstract

Critical periods are times of pronounced brain plasticity. During a critical period in the postnatal development of the visual cortex, the occlusion of one eye triggers a rapid reorganization of neuronal responses, a process known as ocular dominance plasticity. We have shown that the transplantation of inhibitory neurons induces ocular dominance plasticity after the critical period. Transplanted inhibitory neurons receive excitatory synapses, make inhibitory synapses onto host cortical neurons, and promote plasticity when they reach a cellular age equivalent to that of endogenous inhibitory neurons during the normal critical period. These findings suggest that ocular dominance plasticity is regulated by the execution of a maturational program intrinsic to inhibitory neurons. By inducing plasticity, inhibitory neuron transplantation may facilitate brain repair.

Once in life, a critical period for ocular dominance plasticity is initiated by the development of intracortical inhibitory synaptic transmission (1). Reduction of inhibitory transmission disrupts ocular dominance plasticity (2), whereas the early enhancement of inhibitory transmission promotes a precocious period of ocular dominance plasticity (3–6). After the critical period has passed, however, direct pharmacological augmentation of inhibitory transmission does not induce plasticity (7).

Cortical inhibitory neurons are produced in the medial and caudal ganglionic eminences of the embryonic ventral forebrain (8–10). When transplanted into the brains of older animals, embryonic inhibitory neuron precursors disperse widely (11) and develop the characteristics of mature cortical inhibitory neurons (12). We have used repeated optical imaging of intrinsic signals (13, 14) to examine whether inhibitory neuron transplantation produces ocular dominance plasticity after the critical period (fig. S1).

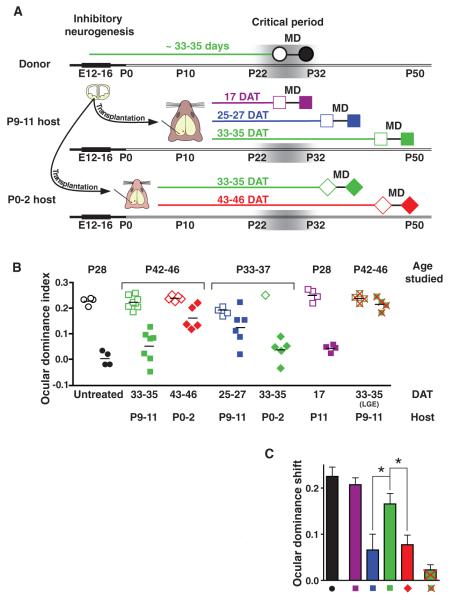

In mice, ocular dominance plasticity reaches a peak in the fourth postnatal week, when cortical inhibitory neurons are ~33 to 35 days old (3, 10) (Fig. 1A). At this age, monocular visual deprivation shifts neuronal responses in the binocular visual cortex away from the deprived eye and toward the nondeprived eye. Throughout this study, we have quantified the balance of cortical responses to the two eyes by calculating an ocular dominance index (ODI). An ODI value of −1 indicates responses dominated by the ipsilateral eye, a value of 1 represents responses dominated by the contralateral eye, and a value of 0 represents equal binocular responses. In untreated mice at the peak of the critical period [postnatal day 28 (P28)], the binocular visual cortex responded more to the contralateral eye, with a mean ODI of 0.22 (Fig. 1B, open black circles). After four days of visual deprivation of the contralateral eye, cortical responses were shifted toward the ipsilateral eye, with a mean ODI value of 0.00 (Fig. 1B, filled black circles).

Fig. 1.

Ocular dominance plasticity induced by transplantation of inhibitory neuron precursors. (A) Experimental design. Cortical inhibitory neurons are produced from E12 to 16. Mouse ocular dominance plasticity peaks at P26 to 28, when inhibitory neurons are 33 to 35 days old. Inhibitory neuron precursors were transplanted from E13.5 to 14.5 donor embryos into host animals of two ages: P0 to 2 (diamonds) and P9 to 11 (squares). Ocular dominance plasticity was assessed 17 (purple), 25 to 27 (blue), 33 to 35 (green), and 43 to 46 (red) DAT by measuring visual responses to the two eyes before (open symbols) and after (solid symbols) 4 days of monocular deprivation (MD). Visual responses were quantified using an ODI. (B) Results of plasticity studies. During the critical period (P28) in untreated mice, monocular deprivation shifted responses toward the nondeprived eye (open versus filled black circles). In P42 to 46 host animals, 14 to 18 days after the critical period, monocular deprivation produced a strong shift in responses 33 to 35 DAT (solid green squares). However, 43 to 46 DAT, monocular deprivation produced a weaker shift in responses (solid red diamonds). In P33 to 37 host animals, 5 to 9 days after the critical period, monocular deprivation produced a stronger effect 33 to 35 DAT (solid green diamonds) than at 25 to 27 DAT (solid blue squares). Transplantation did not alter the effects of monocular deprivation during the critical period (solid purple squares), as compared with untreated controls (solid black circles; Mann-Whitney test, U = 1, P = 0.057). Monocular deprivation produced an insignificant effect at 33 to 35 DAT using cells from the LGE (U = 4, P = 0.343, solid green squares with red crosses). (C) An ocular dominance shift quantified the change in ODI produced by monocular deprivation. Thirty-three to 35 DAT (green) the shift was 2.5 times as high as at 25 to 27 DAT (blue; P < 0.05) and 2.2 times as high as at 43 to 46 DAT (red; P < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test; H = 8.6 with Dunn’s post test). The shift observed 33 to 35 DAT (green) was 77% of that observed in untreated animals during the critical period (black). Error bars represent SEM.

We first examined whether inhibitory neuron transplantation induced ocular dominance plasticity 14 to 18 days after the critical period, at P42 to 46. We transplanted cells from the embryonic day 13.5 to 14.5 (E13.5 to 14.5) medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) into sites flanking the host primary visual cortex at two ages, P0 to 2 and P9 to 11, respectively (Fig. 1A). Host mice that received transplants at P9 to 11 were thus studied 33 to 35 days after transplantation (DAT), whereas hosts that received transplants at P0 to 2 were studied 43 to 46 DAT. Transplantation did not alter the absolute magnitudes of visual responses in the host binocular visual cortex (fig. S2). Before monocular deprivation, host cortex responded more to the contralateral eye (Fig. 1B; P9 to 11 hosts, 33 to 35 DAT ODI mean ± SD = 0.23 ± 0.02, open green squares; P0 to 2 hosts, 43 to 46 DAT ODI = 0.24 ± 0.01, open red diamonds). Monocular deprivation shifted visual responses toward the nondeprived eye 33 to 35 DAT into P9 to 11 hosts (Fig. 1B, ODI = 0.05 ± 0.06, solid green squares). By contrast, monocular deprivation produced much weaker effects 43 to 46 DAT into P0 to 2 animals (Fig. 1B, ODI = 0.16 ± 0.04, solid red diamonds, Mann-Whitney test, U = 1, P = 0.005), consistent with earlier descriptions of the normal decline of ocular dominance plasticity after the critical period (15, 16). These findings demonstrate that transplantation into P9 to 11 animals induces ocular dominance plasticity 33 to 35 DAT, 14 to 18 days after the peak of the critical period.

It remained unclear why transplantation into P0 to 2 hosts did not produce plasticity. We reasoned that the effects of transplantation may have been determined by the age of the host at transplantation (P0 to 2 versus P9 to 11) or by the cellular age of the transplanted population at the time of monocular deprivation (43 to 46 DAT versus 33 to 35 DAT). To distinguish between these possibilities, we transplanted into P0 to 2 and P9 to 11 hosts and then studied plasticity at P33 to 37, shortly after the critical period. Mice transplanted at P0 to 2 were thus studied 33 to 35 DAT, whereas animals transplanted at P9 to 11 were studied 25 to 27 DAT. Monocular deprivation elicited a strong effect 33 to 35 DAT into P0 to 2 hosts (Fig.1B; ODI = 0.04 ± 0.05, solid green diamonds) but produced a much weaker effect 25 to 27 DAT to P9 to 11 hosts (Fig. 1B; ODI = 0.13 ± 0.07, solid blue squares; U = 13, P = 0.035). Thus, transplantation into both P0 to 2 and P9 to 11 hosts could produce plasticity, depending on the age of the transplanted cells at the time of monocular deprivation: Transplantation was effective when the cells were 33 to 35 days old but not when the cells were 25 to 27 or 43 to 46 days old.

These results showed that inhibitory neuron transplantation induced plasticity after the critical period, but they did not establish whether transplantation altered the normal plasticity at the peak of the critical period. We therefore studied plasticity 17 DAT into P11 animals (Fig. 1B, solid purple squares). At this age, monocular deprivation produced similar effects in hosts and age-matched, untreated animals (17 DAT ODI = 0.04 ± 0.01; untreated P28 control ODI = 0.00 ± 0.01; U = 1, P = 0.057). This finding, taken together with the results observed 25 to 27 and 33 to 35 DAT, indicates that transplantation produces a novel period of ocular dominance plasticity, rather than a delay or lengthening of normal critical period plasticity.

To determine whether the effects of transplantation were specific to the introduction of inhibitory precursors from the MGE, we transplanted cells from the lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE), an embryonic ventral forebrain region that produces olfactory bulb inhibitory neurons and striatal medium spiny neurons (17) (fig. S3). The transplantation of E13.5 LGE cells into P9 to 11 hosts did not produce a significant effect on ocular dominance plasticity 33 to 35 days later (Fig. 1B; before monocular deprivation, ODI = 0.24 ± 0.02, open green squares with red crosses; after monocular deprivation, ODI = 0.22 ± 0.03, solid green squares with red crosses; U = 4, P = 0.343). The transplantation of freeze-thawed, dead MGE cells also produced little plasticity (fig. S4; before monocular deprivation, ODI = 0.24 ± 0.01; after monocular deprivation, ODI = 0.19 ± 0.03), further suggesting that the effects of transplantation were specifically caused by live MGE cells (live cell 33 to 35 DAT versus dead cell ODI after monocular deprivation, U = 0, P = 0.006).

Many of our results were obtained by measuring visual responses in the same host before and after monocular deprivation. For each animal, we calculated an ocular dominance shift, the difference between ODIs measured before and after monocular deprivation (Fig. 1C). The ocular dominance shift observed 33 to 35 DAT into P9 to 11 hosts (green) was 77% of that observed in untreated animals during the critical period (black). The effects of transplantation 33 to 35 DAT into P9 to 11 hosts were more than double those produced 25 to 27 DAT (blue) and 43 to 46 DAT (red). These findings indicate that transplantation has its strongest effect on plasticity when the transplanted cells reach a cellular age of 33 to 35 days. This age matches the age of endogenous inhibitory neurons at the peak of the normal critical period (10, 15).

In most of our experiments, cells expressing a red fluorescent protein (DsRed) (18) were transplanted into hosts containing endogenous inhibitory neurons expressing green fluorescent protein (GAD67-GFP) (19). In other experiments, cells expressing GFP (20) were transplanted into wild-type hosts. The transplantation of DsRed cells into GAD67-GFP hosts was done to facilitate the identification of the transplanted and host inhibitory cells in electrophysiological recordings. Transplantation of GFP donor cells into wild-type hosts permitted the detailed histological characterization of the transplanted cells. The effects of monocular deprivation in wild-type host animals 33 to 35 DAT were similar to those observed in GAD67-GFP hosts (fig. S5; wild-type ODI = 0.04 ± 0.03; GAD67-GFP ODI = 0.05 ± 0.06).

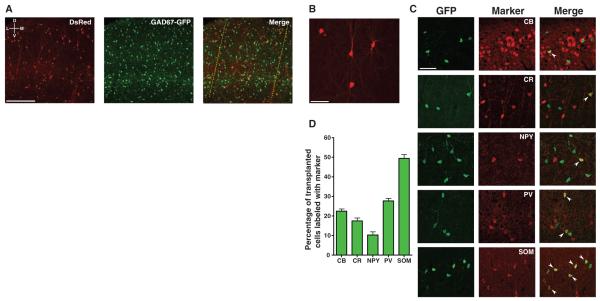

We next examined whether transplanted MGE cells migrated into the primary visual cortex and developed into inhibitory neurons. After the optical imaging experiments, we labeled the borders of host binocular visual cortex with DiI injections and studied the morphologies, molecular pheno-types, spatial distributions, and densities of transplanted cells within the DiI-labeled binocular visual cortex. Across all experimental groups, transplanted cells had migrated into all layers of the host visual cortex (Fig. 2A). Essentially all transplanted cells studied (17 DAT to 43 to 46 DAT) developed morphologies of mature inhibitory neurons (99.8%, Fig. 2B), whereas a very small fraction developed morphologies of glia (0.2%). In P9 to 11 hosts studied 33 to 35 DAT, nearly half of the transplanted neurons (49.5 ± 2.0%) expressed somatostatin, whereas over one-quarter expressed parvalbumin (27.7 ± 1.4%) (Fig. 2, C and D) (21, 22). Smaller fractions of the transplanted neurons expressed calretinin (17.5 ± 1.6%), calbindin (22.5 ± 1.2%), and neuropeptide Y(10.3 ± 1.7%). Awide range of transplanted cell densities were sufficient to induce plasticity 33 to 35 DAT (fig. S6). Variations in the total transplanted cell densities and spatial distributions (fig. S7) could not account for why transplant-induced plasticity was greatest 33 to 35 DAT.

Fig. 2.

Transplanted MGE cells migrate into binocular visual cortex and develop properties of mature inhibitory neurons. (A) Host cortex labeled for transplanted DsRed (red) and host GAD67-GFP (green) inhibitory neurons. DiI injections (red; dotted yellow line for emphasis) labeled the boundaries of binocular visual cortex, as identified by intrinsic signal imaging. Images are oriented with dorsal at top and lateral at left. (B) Detailed view of transplanted DsRed cell morphology. (C) To characterize the expression of inhibitory neuron molecular markers in the transplanted population, E13.5 to 14.5 MGE cells expressing GFP under the beta-actin promoter were transplanted into P9 to 11 wild-type hosts. Transplanted cells were immunostained for GFP (green), calbindin (CB), calretinin (CR), neuropeptide Y (NPY), parvalbumin (PV), or somatostatin (SOM). White chevrons identify colabeled cells. (D) Quantification of marker expression (N = 6 animals). Error bars represent SEM. Scale bars: 250 μm (A), 50 μm [(B) and (C)].

Because of evidence indicating that parvalbumin-expressing inhibitory neurons may regulate critical period ocular dominance plasticity (1, 5, 6), we examined whether the groups studied at 17, 25 to 27, and 43 to 46 DAT had also received transplanted populations that included parvalbumin-expressing cells (fig. S8). At all ages studied, parvalbumin-expressing cells made up a fraction of the transplanted populations and the fraction of parvalbumin-expressing cells increased with the cellular age of the transplanted population. Thus, the lack of plasticity at 25 to 27 DAT and 43 to 46 DAT cannot be attributed to an absence of parvalbumin-expressing transplanted cells in these groups. Instead, the cellular age of the transplanted population determines the effects on cortical plasticity.

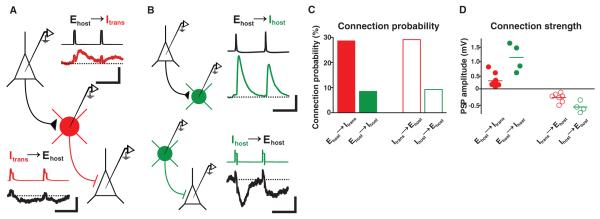

We next examined whether transplanted neurons provided new inhibition to host visual cortex by making whole-cell current-clamp recordings from transplanted and host neurons (12, 23). Transplantation was performed into P0 to 2 or P9 to 11 hosts, and recordings were made from host brain slices at 36 ± 3 DAT (mean ± SD; host ages P43 ± 4), when transplant-induced plasticity was strongest. Transplanted inhibitory neurons (Itrans) received excitatory synapses and made inhibitory synapses with host excitatory neurons (Ehost) (Fig. 3A). We compared the connection probabilities and synaptic strengths of transplanted neurons with those of adjacent host inhibitory neurons in the same slices (Ihost; P45 ± 6; 38 ± 4 DAT) (Fig. 3B). Compared with host inhibitory neurons, transplanted inhibitory neurons were three times as likely to receive synapses from host excitatory neurons, and were also three times as likely to make inhibitory synapses onto host excitatory neurons (Fig. 3C; connection probability Ehost-to-Itrans = 10/35 or 28.6%; Ehost-to-Ihost = 4/47 or 8.5%, P < 0.04; Itrans-to-Ehost = 7/24 or 29.2%; Ihost-to-Ehost = 4/43 or 9.3%, P < 0.05). The synapses received and made by transplanted inhibitory neurons were about one-third as strong as host-to-host synapses [Fig. 3D; synaptic strength, Ehost-to-Itrans EPSPs (excitatory postsynaptic potentials) = 0.34 ± 0.07 mV; Ehost-to-Ihost EPSPs = 1.1 ± 0.24 mV, P < 0.05; Itrans-to-Ehost IPSPs (inhibitory postsynaptic potentials) = −0.24 ± 0.06 mV; Ihost-to-Ehost IPSPs = −0.56 ± 0.09, P < 0.03]. These results demonstrate that transplanted inhibitory neurons form weak but numerous synaptic connections with neighboring excitatory neurons, widely modifying inhibitory signaling in host cortex. The presence of numerous connections between transplanted inhibitory neurons and the host brain may explain why lower transplanted cell densities (fig. S6) were sufficient to induce plasticity.

Fig. 3.

Transplanted inhibitory neurons make and receive numerous, weak synaptic connections. Whole-cell recordings made from fluorescent transplanted inhibitory cells (Itrans, red), host inhibitory cells (Ihost, green), and nonfluorescent putative pre- and postsynaptic pyramidal cell partners (Ehost). Loose-patch stimulation was sometimes used to trigger presynaptic cells. (A) Whole-cell recording from a transplanted inhibitory cell. Loose-patch stimulation of a presynaptic pyramidal neuron evoked EPSPs in the transplanted cell. Transient depolarization of the transplanted neuron evoked IPSPs in a different postsynaptic pyramidal cell. Scale bars: 25 ms, 90 mV (presynaptic); 25 ms, 0.125 mV (postsynaptic). (B) Recordings from pairs of host pyramidal and host inhibitory cells. (Top) Dual whole-cell recording of a presynaptic pyramidal cell and a postsynaptic Ihost. (Bottom) Loose-patch stimulation of a presynaptic host inhibitory neuron and whole-cell recording of a postsynaptic pyramidal cell. Scale bars: 25 ms, 40 mV (presynaptic); 25 ms, 0.25 mV (postsynaptic). (C) Connection probabilities for host-transplanted (red) and host-host (green) cell pairs. Transplanted inhibitory neurons made and received about three times as many connections as host inhibitory neurons (P < 0.05; two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). (D) Connection strengths for all connected host-transplant and host-host cell pairs. Inhibitory and excitatory synapses made and received by transplanted cells were about one-third as strong as synapses of host inhibitory cells (P < 0.05).

Our results show that inhibitory neuron transplantation induces ocular dominance plasticity after the normal critical period. Thirty-three to thirty-five days after transplantation, monocular deprivation produced a shift in visual responses comparable to that observed during the normal critical period (Fig. 1C). However, at shorter and longer intervals after transplantation (25 to 27 and 43 to 46 DAT, respectively), the effect of monocular deprivation was much smaller (Fig. 1C). Thus, transplant-induced plasticity resembles critical period plasticity in two ways: First, transplant-induced and critical period plasticity both peak when the transplanted and endogenous inhibitory neurons reach cellular ages of 33 to 35 days, respectively. Second, both transplant-induced and critical period plasticity are of short duration. Within the binocular visual cortex, the vast majority of transplanted cells expressed the morphological and molecular characteristics of mature inhibitory neurons. Transplanted inhibitory neurons received excitatory synapses from host neurons and made inhibitory synapses onto host neurons. These synaptic contacts were individually weaker but more numerous than those made by host inhibitory neurons.

At a host age when transplanted inhibitory neurons induce plasticity (P42 to 46), the direct pharmacological enhancement of inhibition does not (7). How then, might inhibitory neuron transplantation produce a new period of cortical plasticity? One plausible explanation is that transplanted inhibitory neurons reorganize the cortical circuitry by introducing a new set of weak inhibitory synapses (6), rather than simply augmenting the strength of the endogenous, mature inhibitory connections. This pattern of numerous, weak connections is consistent with the form of developing inhibition predicted to enhance Hebbian plasticity mechanisms during the critical period (24).

Cortical plasticity can be produced after the critical period by the activation of neuromodulatory systems (25, 26) and the manipulation of molecules that promote structural plasticity (27). Each of these manipulations was associated with an accompanying reorganization of inhibitory circuits. Perhaps these experimental manipulations stimulate endogenous inhibitory neurons to form numerous, weak inhibitory synapses similar to those produced by transplanted inhibitory neurons.

It is remarkable that transplanted inhibitory neurons induce plasticity when they reach a cellular age similar to that of endogenous inhibitory neurons during the critical period. This finding suggests (i) that the critical period is regulated by the execution of a developmental program intrinsic to inhibitory neurons and (ii) that embryonic inhibitory neuron precursors retain and execute this program when transplanted into the postnatal cortex. Inhibitory neuron transplantation provides a new experimental preparation for the study of cortical plasticity. Moreover, by promoting cortical plasticity, inhibitory neuron transplantation may facilitate the restoration of normal function to the diseased brain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

28. We thank A. Kriegstein, P. Parker, and members of the Kriegstein laboratory for help with the electrophysiological recordings, R. Romero for assistance with histology, and P. McQuillen for sharing histology equipment. This work was funded by grants R01 NS048528 (A.A.-B.) and P50 MH077972 (M.P.S.) from the National Institutes of Health, grant P0001351 from the Dana Foundation (M.P.S.), and a grant from the Adelson Medical Research Foundation (M.P.S.). D.G.S. was supported by a predoctoral training grant from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. S.P.G. was supported by postdoctoral fellowship EY016317 from the National Institutes of Health. R.C.F. is a recipient of a NIDCD K99/R00 Career Award.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/327/5969/1145/DC1 Materials and Methods Figs. S1 to S9 References

References and Notes

- 1.Hensch TK. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;27:549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hensch TK, et al. Science. 1998;282:1504. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang ZJ, et al. Cell. 1999;98:739. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanover JL, Huang ZJ, Tonegawa S, Stryker MP. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:RC40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-j0003.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagiolini M, et al. Science. 2004;303:1681. doi: 10.1126/science.1091032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugiyama S, et al. Cell. 2008;134:508. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagiolini M, Hensch TK. Nature. 2000;404:183. doi: 10.1038/35004582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson SA, Eisenstat DD, Shi L, Rubenstein JL. Science. 1997;278:474. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nery S, Fishell G, Corbin JG. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:1279. doi: 10.1038/nn971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wonders CP, Anderson SA. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:687. doi: 10.1038/nrn1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wichterle H, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Herrera DG, Alvarez-Buylla A. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:461. doi: 10.1038/8131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvarez-Dolado M, et al. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:7380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1540-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cang J, Kalatsky VA, Löwel S, Stryker MP. Vis. Neurosci. 2005;22:685. doi: 10.1017/S0952523805225178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaneko M, Hanover JL, England PM, Stryker MP. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:497. doi: 10.1038/nn2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon JA, Stryker MP. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:3274. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taha S, Hanover JL, Silva AJ, Stryker MP. Neuron. 2002;36:483. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00966-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wichterle H, Turnbull DH, Nery S, Fishell G, Alvarez-Buylla A. Development. 2001;128:3759. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.19.3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vintersten K, et al. Genesis. 2004;40:241. doi: 10.1002/gene.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamamaki N, et al. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003;467:60. doi: 10.1002/cne.10905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadjantonakis AK, Gertsenstein M, Ikawa M, Okabe M, Nagy A. Mech. Dev. 1998;76:79. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawaguchi Y, Kubota Y. Cereb. Cortex. 1997;7:476. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.6.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonchar Y, Wang Q, Burkhalter A. Front. Neuroanat. 2008;1:1. doi: 10.3389/neuro.05.003.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maffei A, Nataraj K, Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Nature. 2006;443:81. doi: 10.1038/nature05079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gandhi SP, Yanagawa Y, Stryker MP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:16797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806159105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Froemke RC, Merzenich MM, Schreiner CE. Nature. 2007;450:425. doi: 10.1038/nature06289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vetencourt J. F. Maya, et al. Science. 2008;320:385. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pizzorusso T, et al. Science. 2002;298:1248. doi: 10.1126/science.1072699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.