Abstract

Caenorhabditis elegans mab-9 mutants are defective in hindgut and male tail development because of cell fate transformations in two posterior blast cells, B and F. We have cloned mab-9 and show that it encodes a member of the T-box family of transcriptional regulators. MAB-9 localizes to the nucleus of B and F and their descendents during development, suggesting that it acts cell autonomously in the posterior hindgut to direct cell fate. T-box genes related to brachyury have also been implicated in hindgut patterning, and our results support models for an evolutionarily ancient role for these genes in hindgut formation.

Keywords: C. elegans, hindgut, T-box, brachyury, development

An important question in developmental biology is how cell fates are allocated in the correct pattern. Developmental patterning requires that certain cells become different from one another at the appropriate time, but there are few molecular clues at present as to how this process is properly regulated. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans provides a unique set of tools for the analysis of cell fate determination because the fate of each cell during development is invariant and well characterized (Sulston et al. 1980, 1983). The effects of mutations on cell fate determination during development can therefore be analyzed at single-cell resolution. Mutations that transform correct cell fates into other, inappropriate, fates are likely to define genes that have key roles in allocating cell fate identity.

Many aspects of C. elegans development have been subjected to genetic analysis. One well-defined set of mutants, Mab (male abnormal), are defective in the development of structures which make up the male tail, the copulatory structure of the worm (Hodgkin 1983). The male tail includes the proctodeum, that houses two sclerotized spicules and associated musculature used for the transfer of sperm, as well as a cuticular fan containing sensory rays used to locate the hermaphrodite vulva during mating (Sulston et al. 1980).

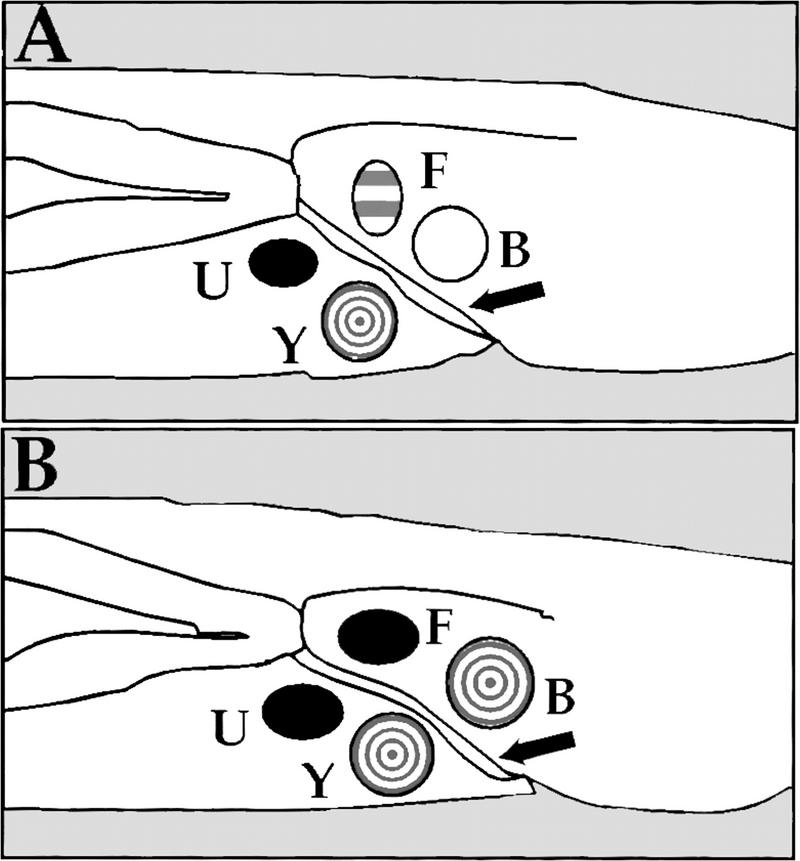

mab-9 mutants form grossly disorganized male tails because of changes in the developmental fates of two posterior blast cells, B and F (Chisholm and Hodgkin 1989). The most obvious defect in mab-9 males results from the blast cell B taking on the lineage fate of its anterior neighbor Y (Fig. 1). As B is the major male-specific blast cell, giving rise to 42 cells that make up most of the internal structures of the male tail including the copulatory spicules (Sulston et al. 1980), the absence of a B lineage in mab-9 mutants results in a grossly abnormal male tail lacking spicules, rendering males incapable of mating. Similarly, the minor tail blast cell F generates an abnormal lineage in mab-9 mutants, which appears to resemble that of its anterior neighbor U (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Cell fate transformations in mab-9 mutants. Schematic of cell lineage fates in wild-type and mab-9 males. The pattern of blast cell identities in L1 males is shown. (A) Wild type. Blast cells B, Y, U, and F have distinct lineage programs that are executed during larval development. These four cells straddle the developing rectum (arrow) in two neighboring pairs, B/Y and F/U, with B and F being the posterior member of each neighboring pair. (B) mab-9 mutant. B takes on the subsequent lineage fate of Y, and F takes on the lineage fate of U. These two cell lineage transformations account for the phenotypes observed in mab-9 mutant worms.

mab-9 does not act solely in males to control the identity of B and F: In hermaphrodites, these two cells do not divide but form part of the structure of the rectum. Consequently, hermaphrodites mutant for mab-9 have hindgut defects resulting in constipation. The normal function of mab-9, therefore, in both sexes, is to provide the hindgut cells B and F with their characteristic identities, thereby distinguishing them from their anterior neighbors Y and U. The Mab phenotype in males can be regarded as a hindgut defect because the parts of the male tail affected are derived from the specialized hindgut blast cells B and F. mab-9 mutants of both sexes are also slightly uncoordinated (Unc) for backward movement (Chisholm and Hodgkin 1989), although the reason for this is unclear.

In this report we show that mab-9 encodes a member of the T-box family of transcriptional regulators. The prototype member of this family of DNA-binding proteins, Brachyury, or T, was originally isolated as a mutation in mouse affecting tail development (Chesley 1935). Brachyury has since been shown to be important for the development of the notochord (Herrmann et al. 1990; Schulte-Merker et al. 1994) and induction of mesoderm (Wilkinson et al. 1990). Brachyury homologs have now been discovered in many other species and have been shown to have conserved roles during development (for review, see Smith 1999). In addition, it has become clear that there is a large family of transcriptional regulators that share a conserved DNA-binding domain, the so-called T-box, with Brachyury (Pflugfelder et al. 1992; for review see Smith 1997). This set of genes can be divided into a number of subfamilies based on the sequence of the DNA-binding domain (Agulnik et al. 1997; Wattler et al. 1998).

There are 19 T-box genes in C. elegans predicted by the completed sequencing project, although there does not appear to be an obvious Brachyury homolog (Ruvkun and Hobert 1998). mab-9 is more similar to T-box genes from other species than it is to other C. elegans T-box genes, many of which are highly diverged. In Drosophila, the Brachyury homolog, brachyenteron (byn), is required for the development of the hindgut (Kispert et al. 1994). The similar function of mab-9 in C. elegans suggests a striking conservation of function between the roles of these two T-box genes during development.

Results and Discussion

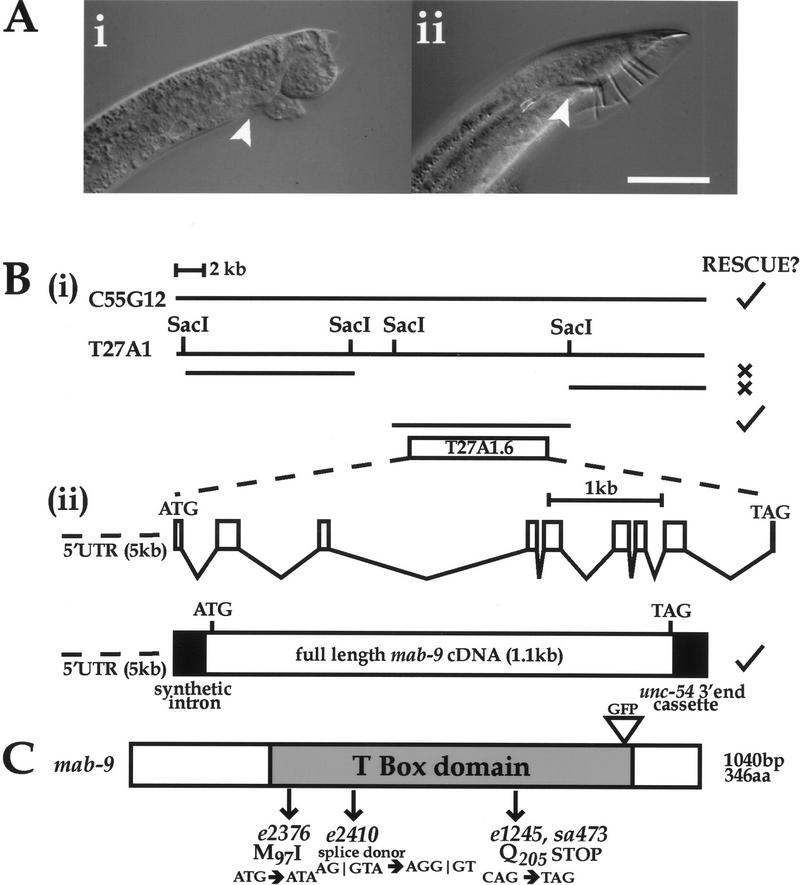

mab-9 encodes a T-box gene

mab-9 was mapped previously to the left arm of LGII between egl-26 and lin-42 (Chisholm and Hodgkin 1989). We refined this map position further using the polymorphic marker veP2 (gift of Ann Rougvie, University of Minnesota, St. Paul) and the physical map position of sup-9 (I. Perez de la Cruz and H.R. Horvitz, pers. comm.). Cosmids from the corresponding genomic region were then injected into mab-9(e2410); him-8(e1489) animals to assay for rescue of male tail defects. Subcloning of the rescuing cosmid C55G12 revealed a 12.9-kb SacI fragment containing a single gene that was capable of complete rescue (Fig. 2A). This single gene corresponds to T27A1.6 (cosmids C55G12 and T27A1 overlap completely; Fig. 2B). T27A1.6 encodes a 346-amino-acid gene (corresponding to a predicted 39.4-kD protein) containing a 200-amino-acid T-box DNA-binding domain (Fig. 2D). A cDNA sequence of this gene has been reported previously as Ce-tbx-12 (Agulnik et al. 1997).

Figure 2.

mab-9 is a T-box gene. (A i) mab9(e2410); him-8(e1489) adult male tail. Note the disorganized appearance of the tail and lack of spicules (arrowhead). (ii) mab-9 (e2410); him-8(e1489); eEx[T27A1.6 + pCes1943] adult male tail. Wild-type appearance is completely restored. Note the properly formed spicules (arrowhead). Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Molecular characterization of mab-9. (i) Cosmid rescue of mab-9 with C55G12. Subcloning was performed on the canonical sequenced cosmid T27A1 and the middle SacI fragment found to rescue. (ii) Genomic structure of the rescuing gene T27A1.6, based on the cDNA sequence. The rescuing cDNA construct, expressed from the mab-9 promoter, is shown below. (C) Domain structure of mab-9. The mutations in mab-9 alleles e2376, e2410, e1245, and sa473 are shown. The position at which GFP was inserted into genomic DNA is indicated. (D) Sequence alignment of T-box domains. The start of the T-box domain of each protein is labeled 1. An alignment of the mab-9 T-box domain (amino acids 76–275 of the whole protein) with those of its two closest relatives, human TBX20 (GenBank accession no. AJ237589) and Drosophila H15 (accession no. X98766) are shown in the first three lines. Identical amino acids are shown in black; similar amino acids are shaded. An alignment with two more distant relatives, Drosophila byn (accession no. S74163, 46% identity) and mouse Brachyury (accession no. X51683, 44% identity) is shown in the bottom two lines. Sequence alignments were performed using ClustalW. The positions of the mutations in mab-9 alleles e2376, e2410, and e1245/sa473 are shown in the above order with an asterisk (*).

To confirm the genomic structure of mab-9 we isolated and sequenced a full-length 1.1-kb cDNA clone from a cDNA library (gift of R. Barstead, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma city). A corresponding fragment was also isolated from N2 worm RNA by RT–PCR as the sole product (data not shown). The cDNA sequence we obtained (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AJ252168) differs in minor detail from that published previously (Agulnik et al. 1997) and is in agreement with the genomic sequence. This cDNA clone rescues mab-9 mutant animals when expressed under the control of the mab-9 promoter, consisting of 5.2 kb of DNA upstream of the initiating ATG (Fig. 2B), although the cDNA rescue is not quite as good as rescue with the genomic construct (data not shown). The genomic structure of mab-9 is shown in Figure 2B and differs slightly at the carboxyl terminus from the Genefinder prediction.

An alignment of mab-9 with its closest T-box relatives, as well as with mouse and Drosophila Brachyury is shown in Figure 2D. T-box genes are characterized by having a large DNA-binding domain of ∼200 amino acids, the T-box domain (Fig. 2C), which is highly conserved between T-box genes from different species. Outside the T-box domain there is very little sequence homology. Analysis of C. elegans T-box genes reveals that they are mostly highly diverged from those described previously from vertebrates, arthropods and ascidians (Agulnik et al. 1997; A. Woollard, unpubl.). Four C. elegans T-box genes, however, mab-9 (T27A1.6), F21H11.3, H14A12.4, and ZK328.6, are much more similar to T-box genes described from other organisms (Agulnik et al. 1997; A. Woollard, unpubl.).

The closest relatives of mab-9 are the human gene TBX20 (63% identity across the T-box region) and the Drosophila gene H15 (54% identity); no functional information is as yet available about these genes. The genomic structure of the T-box domain of many T-box genes is also highly conserved across a wide range of species (Wattler et al. 1998) and typically contains four introns, the first, third, and fourth of which tend to be at identical positions. This conservation of genomic structure suggests a common and ancient evolutionary origin. The intron/exon structure of the T-box domain of mab-9 shares this conserved pattern, whereas other more divergent C. elegans T-box genes lack one or more of them or have them at different positions (Agulnik et al. 1997; A. Woollard, unpubl.).

The mutations found in four alleles of mab-9—e1245, e2410, e2376 (Chisholm and Hodgkin 1989), and sa473 (kindly donated by Helen Chamberlin, Ohio State University, Columbus)—are shown in Figure 2, C and D. The amber stop mutation in e1245 and sa473 confirms genetic data indicating that e1245 can be suppressed by the amber suppressor sup-5 (Chisholm and Hodgkin 1989). The mutation in e2410 is a 2-bp change in the splice donor site at the beginning of intron 4, which would be expected to produce a frameshift. e1245 and e2410 have been shown genetically to be likely null mutations, as the phenotype does not deteriorate when placed in trans to a deficiency (Chisholm and Hodgkin 1989). The molecular lesions found in these two mutations support this view, as the mutant protein in each case would lack most of the conserved T-box domain. The mutation in e2376 results in a single-amino-acid change (M97I) and is associated with a slightly weaker phenotype. Met97 is located at the beginning of the T-box domain and is completely conserved in all T-box genes examined. This residue is therefore likely to be important for DNA binding, as the relatively conservative change of M to I results in considerable reduction of function.

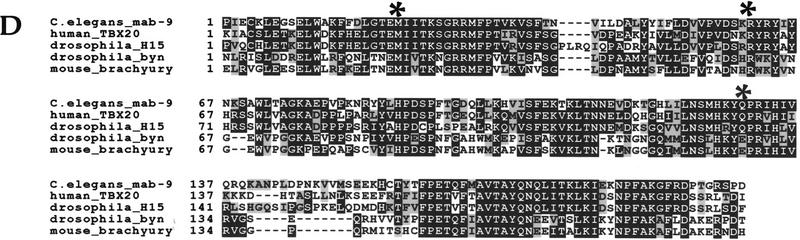

Further confirmation of the null phenotype of mab-9 animals is given by RNA interference experiments (Fire et al. 1998). Gonad injection of double-stranded RNA corresponding to a 600-bp fragment of mab-9 coding sequence results in progeny that phenocopy mab-9 mutants completely (Fig. 3). Hermaphrodite mab-9(RNAi) (RNA interference) animals are constipated and backward Unc to the same degree as the strong loss-of-function alleles e2410 and e1245, whereas males have grossly abnormal tails with no spicules. The penetrance of these phenotypes was found to be up to 100% in progeny hatching 8 hr or more after injection of the parent.

Figure 3.

mab-9 RNAi. (A) him-8(e1489) adult male tail. (Arrowhead) Spicules. (B) mab-9(e2410); him-8(e1489) adult male tail. (C) Male progeny of him-8(e1489) hermaphrodite injected with dsRNA corresponding to part of mab-9. Note disorganized tail and lack of spicules (arrowhead). (D) Hermaphrodite mab-9(RNAi) adult. Note deformed anal region. (Arrowhead) The intestinal lumen, which is distended in these constipated worms. (E) Wild-type hermaphrodite. (Arrowhead) The rectum. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Expression pattern of mab-9

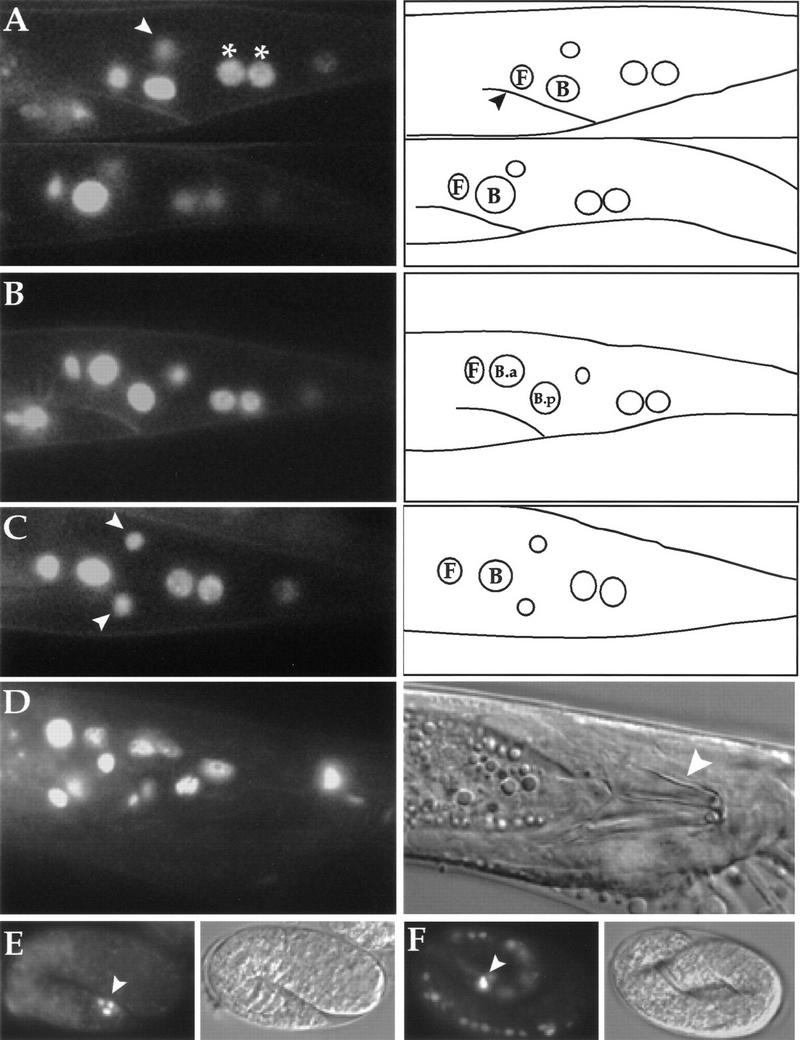

A green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter construct in which GFP was inserted in-frame into exon 7 of the rescuing mab-9 construct was found to retain its rescuing activity when present in mab-9(e2410); him-8(e1489) animals as an extrachromosomal array and when the construct was integrated. This indicates that a sufficient mab-9 expression pattern is maintained under these conditions. The expression pattern of mab-9::GFP is shown in Figure 4. mab-9 localizes to the nucleus and is expressed in very few cells throughout development. In L1 larvae, mab-9::GFP expression is seen in the posterior hindgut cells B and F (Fig. 4A), the two cells that take on inappropriate lineage fates in mab-9 mutants. Note the larger size of the B blast cell nucleus in males (Fig. 4A, bottom left) compared to hermaphrodites (top left), where B is not a blast cell. This is one of the first visible sexual dimorphisms in C. elegans (Sulston and Horvitz 1977). Expression is also seen in two posterior hypodermal nuclei of the large syncytial cell hyp7 (Fig. 4A–C) and in the nervous system, where mab-9::GFP expression is evident in two neuronal nuclei of the lumbar ganglion. Given their relative position between B and hyp7 (Fig. 4C), these are most likely to be the two nuclei of the interneuron PVC (Sulston et al. 1983; White et al. 1986). In addition, mab-9::GFP expression is always observed in a single neuronal nucleus of the head ganglion (not shown). The neuronal and hypodermal expression pattern of mab-9 is the same in males and hermaphrodites.

Figure 4.

Localisation of mab-9. CCD images of mab-9::GFP fluorescence. Posterior is to the right; dorsal is up. (A) (Top left) Hermaphrodite L1 larva, lateral view. (Top right) Tracing with the position of the rectum marked (arrowhead) and the relative positions of B and F nuclei shown. The white arrowhead (top left) indicates one of a pair of neuronal nuclei expressing mab-9::GFP, slightly out of the focal plane. The two posterior hyp7 nuclei are marked with asterisks (*). (Bottom left) Male L1 larva. Note the larger size of the B nucleus. (B) L2 male. B has divided into the larger B.a and the smaller B.p, and GFP expression is seen in both daughters. B does not divide in hermaphrodites. (C) Ventral view, hermaphrodite L3. The pair of neuronal nuclei is now clearly visible in the focal plane (white arrowheads). The relative positions of the B and F nuclei are shown in the tracing at right. (D) Late L4 male, ventral view. B lineage nuclei of cells associated with the spicule expressing mab-9::GFP can be seen in this focal plane. A Nomarski photomicrograph of this image is shown at right, with the spicules marked by a white arrowhead. (E) A 1.5-fold embryo expressing mab-9::GFP in three posterior cells around the presumptive rectum. Nomarski image shown at right. (F) Three-fold embryo expressing mab-9::GFP. Bright fluorescence is observed in the B and F rectal cells (white arrowhead). Expression is also observed transiently in ventral cord nuclei. Nomarski image shown at right (embryo is moving by this stage).

During late L1 in males, B divides unequally to give rise to the larger anterior daughter B.a and the smaller posterior daughter B.p (Sulston and Horvitz 1977). This division can be seen clearly in Figure 4B, where mab-9::GFP expression is observed in both daughters. In late larval males, the expression pattern of mab-9 is more widespread in nuclei of the proctodeum, as a result of cell divisions in the B and F lineages (Fig. 4D). In adult hermaphrodites, mab-9::GFP expression is maintained in the same six cells that expressed mab-9 during larval development (not shown). This suggests that mab-9 may be required for the maintenance of B and F cell fates (and lineages in males), as well as for their primary determination. A construct in which a 5.2-kb mab-9 promoter-only cassette was cloned in front of GFP (vector pPD96.04) was found to have a very similar expression pattern when present in wild-type worms as an extrachromosomal array (data not shown).

mab-9 is also expressed during embryogenesis. mab-9::GFP expression is first seen at the 1.5-fold stage (Fig. 4E), ∼430 min after first cleavage, in three to four nuclei around the presumptive rectum [B, F, and hyp7 (Sulston et al., 1983)]. In threefold embryos (Fig. 4F), mab-9::GFP expression becomes very intense in the nuclei of B and F, and weaker expression can also be observed in nuclei of the ventral cord. This ventral cord expression appears to be transient and is not observed reproducibly as larval development ensues.

The functional significance of mab-9 expression in the nervous system and hypodermis is not clear at this stage. mab-9 mutant worms are known to be slightly backward Unc, a phenotype that is observed in strong loss-of-function alleles (Chisholm and Hodgkin 1989) and in the RNAi experiments described above. It is likely, therefore, that mab-9 has some function in the nervous system.

The Hox gene egl-5, which is required for regional identity within the hindgut and male tail (Chisholm 1991; Chamberlin et al. 1999), is expressed in these tissues (Ferreira et al. 1999) and is therefore a candidate regulator of mab-9 activity. We find, however, that the expression pattern of mab-9::GFP is unchanged in an egl-5(n486) mutant background (data not shown). Similarly, we find that the mab-9 expression pattern is unaltered in a lag-1(q385) mutant background (data not shown). lag-1 is required for the development of the rectum and encodes a homolog of Drosophila suppressor of hairless (Christensen et al. 1996), which is known to activate Brachyury expression in the Ciona embryo (Corbo et al. 1998).

Effects of mab-9 misexpression

The mab-9 cDNA described earlier rescues mab-9(e2410) worms when expressed under the control of the mab-9 promoter. However, when this cDNA is expressed from the strong heat shock promoter hsp-16 (which induces gene expression in all somatic cells), there is no rescue of the mab-9 mutant phenotype either with or without heat treatment. Furthermore, when this construct is present in wild-type worms, induction of mab-9 overexpression by heat shock has deleterious consequences. Heat treatment of young adult worms of the strain eEx88 [hsp16.41::mab-9 + pCes1943] reduces the brood size by ∼63% compared to nontransgenic N2 worms subjected to the same heat treatment [brood sizes: nontransgenic N2, 217 ± 10.7, n = 5; eEx88 (hsp16.41::mab-9 + pCes1943), 81 ± 10.7, n = 5]. This reduction in brood size is caused by embryonic or early larval lethality as judged by the observation of dead embryos and larvae, rather than sterility. Brood sizes of strains not subjected to heat treatment are normal [nontransgenic N2, 267 ± 11, n = 5; eEx88 (hsp16.41::mab-9 + pCes1943), 256 ± 17, n = 5].

Furthermore, hsp16::mab-9 animals that survive the heat treatment are severely backward Unc. Transgenic progeny (larvae and adults) from a hsp16::mab-9 strain subjected to heat treatment coil severely about the posterior when they attempt to move backwards, whereas forward locomotion is relatively normal. Nontransgenic siblings are not Unc (the rate of transmission of the transgene in this strain is ∼70%). This Unc phenotype is again consistent with a possible nervous system role for mab-9, along with the expression pattern and loss-of-function phenotype discussed above. A proportion of transgenic progeny also exhibit a range of other phenotypes including egg-laying deficiency (Egl phenotype) and protruding vulva (Pvl phenotype), although these defects are less penetrant. This indicates that the expression level of mab-9 has to be tightly regulated and limited to very few cells for development to proceed normally.

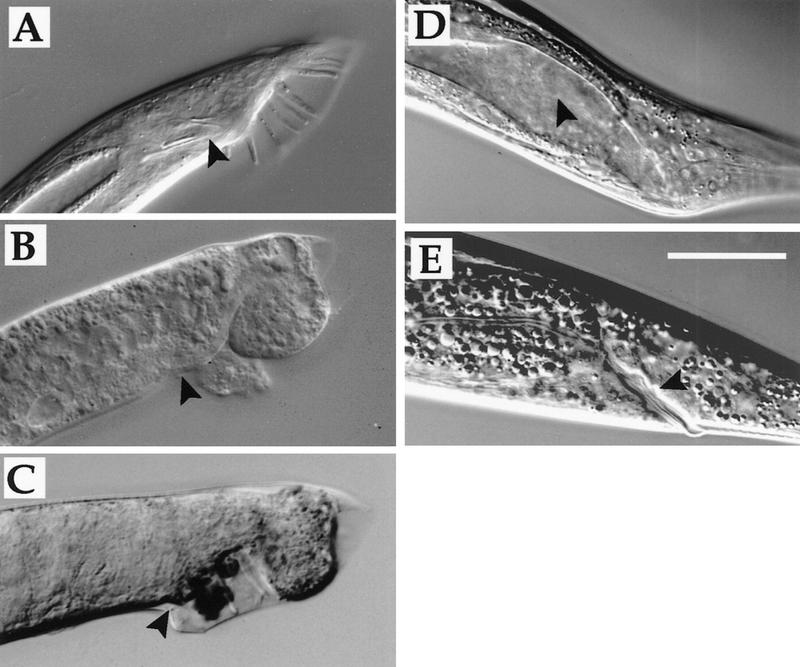

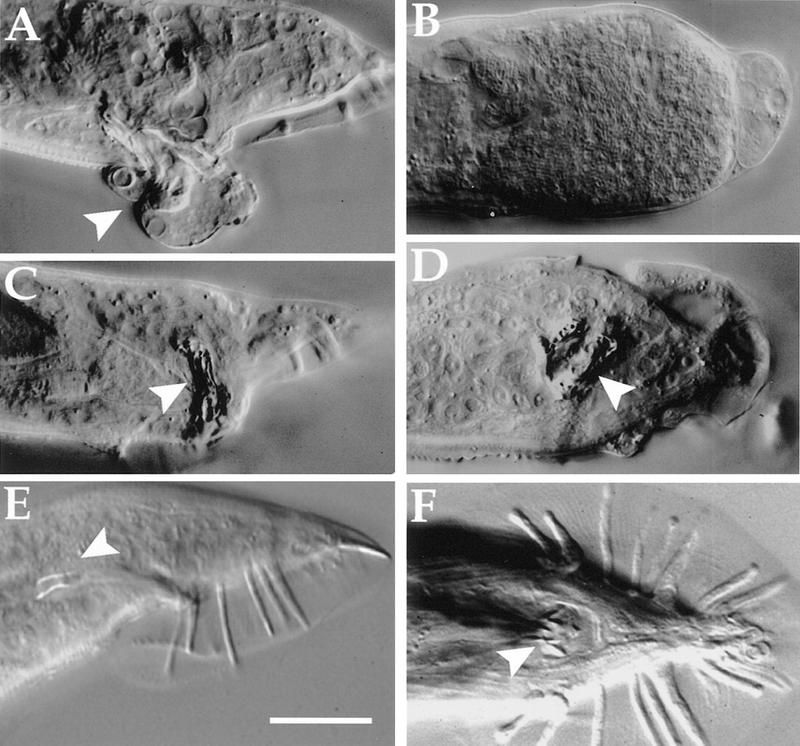

High-level expression of mab-9 in males results in severe defects in tail development of surviving animals (Fig. 5). Some of these males differentiate abnormal refractile masses (Fig. 5C, D), which may be the result of ectopic B-type cell fates.

Figure 5.

Phenotype of worms expressing hsp-16::mab-9. (A–D) Heat-treated adult males of strain him-5(e1490); eEx88 [hsp-16.41::mab-9 + pCes1943]. Note the partially everted rectal epithelium in A (arrowhead) and completely disorganized tail development in B. Abnormal refractile masses can be seen in C (lateral view) and D (ventral view) (arrowheads). Wild-type male tails are shown in E (lateral view) and F (ventral view) for comparison (spicules denoted by arrowheads). Scale bar, 25 μm.

Ancient origin of posterior gut development

mab-9 is the first T-box gene in C. elegans for which a mutant phenotype has been described. There is no obvious Brachyury homolog in the C. elegans genome; however, if BLAST analysis is performed searching the C. elegans genome database with Brachyury homologs such as Drosphila byn, mab-9 comes out with the highest score (A. Woollard, unpubl.). It is striking that the function of mab-9 in C. elegans and byn in Drosophila and other insects (Kispert et al. 1994; Singer et al. 1996) appears to be conserved, at least with respect to the development of the hindgut.

It is well established that Brachyury in mouse and its vertebrate homologs function in the development of the notochord (Herrmann et al. 1990; Schulte-Merker et al. 1994; for review see Smith 1997, 1999). It has been suggested previously that there may be a phylogenetic relationship between the function of byn in the insect hindgut and Brachyury in the vertebrate notochord (Kispert et al. 1994). This hypothesis assumes that the notochord is phylogenetically derived from the stomochord of hemichordates, a structure that evaginates from the gut and leads to the speculation that an ancestral Brachyury-like gene may have specified part of the gut early in evolution. In arthropods, byn became involved in the development of hindgut (and according to this study, mab-9 in nematodes acquired a similar role), whereas in the evolution of chordates, Brachyury, or an ancestral form of this gene, became concerned with the specification of the stomochord (a gut derivative) and eventually the notochord (for further discussion, see Kispert et al. 1994).

One way to test this hypothesis would be to examine the expression pattern of Brachyury in hemichordates. A recent study by Peterson et al. (1999) concludes that Brachyury is not expressed in the stomochord of the enteropneust hemichordate Ptychodera flava at any stage during development. However, although this observation does not support the hypothesis, it does not necessarily disprove it. A Brachyury-like gene distinct from brachury itself could be involved in the specification of the stomochord, or perhaps genes downstream of Brachyury could provide the relationship between notochord and stomochord.

An in-depth survey of comparative data on Brachyury expression has been reported recently (Peterson et al. 1999). This study describes a hypothetical reconstruction of the evolutionary history of Brachyury utilization based on expression data from arthropods, echinoderms, enteropneusts, vertebrates, cephalochordates, and urochordates and concludes that the primitive role of Brachyury was in specification of the posterior gut. The first branchpoint in this scheme was proposed to be the recruitment of Brachyury to the specification of mesoderm, which was thought to occur in all groups except the arthropods. It has since been reported, however, that byn does have a role in mesoderm specification in Drosophila (Kusch and Reuter 1999).

We have now established that a T-box gene related to Brachyury-class T-box genes, mab-9, is concerned with the specification of the posterior gut in C. elegans. Based on this conservation of primitive function we propose that mab-9 may be regarded as the C. elegans Brachyury ortholog. Consequently, it becomes useful to consider the phylogenetic relationship among nematodes, arthropods, and chordates. The classical phylogeny based on morphological criteria (discussed in Blaxter 1998) places nematodes as an outgroup taxon to both arthropods and chordates. This would fit well with our observation that mab-9 is expressed and functions in the posterior gut but not in mesoderm. Some cladistic (Nielson 1995) and molecular (Aguinaldo et al. 1997; Mushegian et al. 1998) phylogenetic analyses, however, challenge the view that nematodes branched off before the arthropod–vertebrate split, and this controversy remains unresolved.

This study shows that mab-9 is expressed in two posterior hindgut cells, B and F, to distinguish these two cells from their anterior neighbors Y and U, respectively. It is noteworthy that B and Y straddle the rectum in a similar position just ventral to F and U. mab-9 therefore functions by distinguishing the posterior members of two distinct but neighboring cell pairs. Two other genes have been identified recently that are required for distinguishing fates within these four hindgut cells. These two genes, egl-38 and lin-48, are also required to make certain cells different from others: egl-38, a Pax type transcription factor, distinguishes F and U from B and Y (Chamberlin et al. 1997), whereas lin-48 distinguishes U from B (Chamberlin et al. 1999). At least two of these genes, mab-9 and egl-38, are transcription factors. The next challenge will be to identify targets of these fate-determining transcriptional controls to establish exactly how these genes might act in combination with each other to pattern the developing hindgut.

Materials and methods

Strains and mapping

All C. elegans strains were derived from the wild-type Bristol strain N2. Genetic manipulations were performed as described (Sulston and Hodgkin 1988). In cases in which male phenotypes were examined Him (high incidence of males) mutant backgrounds were used. mab-9 was mapped previously to the left arm of LGII between lin-42 and egl-26, ∼2.2 cM from sup-9 (Chisholm and Hodgkin 1989). This places mab-9 close to the polymorphic marker veP2. veP2 (cosmid T19G10) was used in three-factor mapping crosses. Sup (non-Unc) non-Mab recombinant males were picked from among the progeny of heterozygote veP2 lin-31 bli-2/mab-9 sup-9 II; unc-93 III, him-5 V and tested by PCR for the presence of veP2 (primers kindly supplied by Ann Rougvie). Of 49 Sup non-Mab males, 33 were found to contain veP2, placing mab-9 <1 cM to the left of veP2. Given the relatively small physical map distances in this part of the genome, cosmids from this region were then injected to test for rescue.

Transformation rescue

Cosmids were injected at concentrations of 2–20 ng/μl into mab-9(e2410); him-8 (e1489) worms as described (Mello and Fire 1995). The plasmid pCes1943 (gift of Diana Janke, University of British Columbia, Varcouner, B.C., Canada) containing the rol-6 dominant marker was coinjected (50 ng/μl) with cosmids so that the dominant Roller (Rol) phenotype could be used as a transformation marker. Stable transgenic lines were picked from F1 animals that produced Rol progeny and males observed for evidence of phenotypic rescue. The cosmid C55G12 was found to rescue when injected at low concentrations (2 ng/μl). This cosmid was then subcloned using standard molecular biological techniques (Sambrook et al. 1989) into pBluescript(+) in three separate fragments using SacI, and the central 12.9-Kb SacI fragment (bp 15351–28223 of the canonical sequenced cosmid T27A1) was found to rescue. This clone (pAW111) was found to contain one complete ORF, designated T27A1.6.

Mutant allele sequencing

A 5-kb genomic fragment covering the mab-9 locus was amplified from wild-type, e1245, e2410, e2376 and sa473 single worms by PCR using the high-fidelity Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). Single-worm PCR was performed as described previously (Williams 1995). Sequences (both strands) of at least two independent PCR products were analyzed.

cDNA analysis

A 1.1-kb cDNA corresponding to mab-9 was isolated from a mixed-stage cDNA library (kind gift of R. Barstead) by PCR using primers just outside of the ORF for Ce-tbx-12 (which corresponds to T27A1.6) predicted by Agulnik et al. (1997). Several clones were sequenced and all were found to differ from the published cDNA clone in small detail. The cDNA sequence reported here (accession no. AJ252168) is in agreement with the genomic sequence reported in AceDB. The cDNA includes an in-frame stop codon just 5′ of the ATG and is therefore judged to be full-length. In addition, this cDNA clone rescues mab-9(e2410) worms when expressed under the control of the mab-9 promoter, albeit slightly less effectively than the genomic construct. The genomic structure of mab-9 predicted by the cDNA (Fig. 2B) differs slightly at the carboxyl terminus from the Genefinder prediction; the Stop codon predicted in the C. elegans genome sequence is spliced out resulting in an extra intron of 841 bp before the final short exon containing only 2 codons prior to the final Stop codon. RT–PCR analysis with primers corresponding to SL1 or SL2 spliced leader sequences failed to yield any product, indicating that mab-9 is not subject to trans-splicing.

RNAi

PCR primers were designed that added a T7 RNA polymerase promoter at the 5′ end of exon 6 (5′-ATTAACCCTCACTAAAGCTAATCCTAAACTCAATGCAC-3′) and a T3 RNA polymerase promoter at the end of exon 8 (5′-AATACGACTCACTATAG CTTTATTGAAATTTCTGCAGG-3′) to amplify a 600-bp fragment of mainly exon sequence that did not share significant homology at the nucleotide level with other C. elegans genes. RNA was synthesized directly from gel-purified PCR product as described (Fire et al. 1998) using 100 to 200-ng template DNA. dsRNA was purified and injected into young N2 adult hermaphrodite gonads at a concentration of ∼1 mg/ml as described (Fire et al. 1998). Injected worms were transferred to fresh plates 6 hr after injection and thereafter every 10–14 hr for 3 days.

GFP fusion

A GFP reporter was excised from plasmid pPD102.33 (kindly supplied by the Fire laboratory vector kit, Carnegie Institute of Washington, Baltimore, MD) and inserted in-frame into the unique BamHI site of mab-9 that resides at the carboxy-terminal end of the T-box domain to produce a mab-9::GFP fusion construct (pAW118) that completely rescues mab-9 worms when present as a transgenic array [strain mab-9(e2410); him-8(e1489); eEx85 (mab-9::GFP + pCes1943)]. Transgenic Rol lines were examined for GFP expression under fluorescence optics. A strain was derived from one rescued line in which the mab-9::GFP array was integrated into the genome, using X-ray mutagenesis as described previously (Mello and Fire 1995). This strain, mab-9(e2410); him-8(e1489); Is34(eEx85), was outcrossed several times and the site of integration mapped to LGIII.

hsp-16 promoter and mab-9 promoter-driven cDNA constructs

mab-9 cDNA was cloned into the heat shock vector pPD49.83 (Fire laboratory Vector kit), which contains the hsp-16 promoter (16.41) followed by a synthetic intron, to produce the heat shock inducible mab-9 construct pAW123. Transgenic N2 or him-5(e1490) lines carrying this construct [+ pCes1943 (rol-6) marker] were picked to fresh plates as young adult hermaphrodites, and plates were heat treated at 33°C for 20 min twice a day (morning and evening). Parent worms were subsequently transferred to fresh plates each day, and each plate was heat-shocked so the whole brood could be monitored. To make a rescuing cDNA construct, the mab-9 promoter region (5.2-kb of 5′-untranslated sequence) was cloned into pPD49.26 (Fire laboratory vector kit) as a PstI–BamHI PCR fragment, upstream of a synthetic intron. mab-9 cDNA was then cloned into this construct downstream of the synthetic intron (SalI–SacI PCR fragment) and upstream of the unc-54 3′-end cassette. This construct (pAW141) was injected into mab-9(e2410); him-8(e1489) worms and Rol lines obtained.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the LMB worm group for advice and discussion, and Shawn Ahmed, Marc Bickle, Mario deBono, and Neil Hopper for helpful comments on the manuscript. We also thank Ann Rougvie for sharing mapping information and markers, Alan Coulson and Ratna Shownkeen for providing cosmids, Andy Fire for providing heat shock and GFP vectors, Bob Barstead for the cDNA library, Helen Chamberlin for sharing alleles and unpublished information, and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for sending strains. This work was supported by the MRC and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL woollard@bioch.ox.ac.uk; FAX 44 (0)1865 275318.

References

- Aguinaldo AM, Turbeville JM, Linford LS, Rivera MC, Garey JR, Raff RA, Lake JA. Evidence for a clade of nematodes, arthropods and other moulting animals. Nature. 1997;387:489–493. doi: 10.1038/387489a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agulnik SI, Ruvinsky I, Silver LM. Three novel T-box genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome. 1997;40:458–464. doi: 10.1139/g97-061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter M. Caenorhabditis elegans is a nematode. Science. 1998;282:2041–2046. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin HM, Palmer RE, Newman AP, Sternberg PW, Baillie DL, Thomas JH. The PAX gene egl-38 mediates developmental patterning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1997;124:3919–3928. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin HM, Brown KB, Sternberg PW, Thomas JH. Characterization of seven genes affecting Caenorhabditis elegans hindgut development. Genetics. 1999;153:731–742. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesley P. Development of the short-tailed mutant in the house mouse. J Exp Zool. 1935;70:429–459. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm A. Control of cell fate in the tail region of C. elegans by the gene egl-5. Development. 1991;111:921–932. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.4.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm AD, Hodgkin J. The mab-9 gene controls the fate of B, the major male-specific blast cell in the tail region of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes & Dev. 1989;3:1413–1423. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen S, Kodoyianni V, Bosenberg M, Friedman L, Kimble J. lag-1, a gene required for lin-12 and glp-1 signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans, is homologous to human CBF1 and Drosophila Su(H) Development. 1996;122:1373–1383. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbo JC, Fujiwara S, Levine M, Di Gregorio A. Suppressor of hairless activates brachyury expression in the Ciona embryo. Dev Biol. 1998;203:358–368. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira HB, Zhang Y, Zhao C, Emmons SW. Patterning of Caenorhabditis elegans posterior structures by the Abdominal-B homolog, egl-5. Dev Biol. 1999;207:215–228. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann BG, Labeit S, Poustka A, King TR, Lehrach H. Cloning of the T gene required in mesoderm formation in the mouse. Nature. 1990;343:617–622. doi: 10.1038/343617a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin J. Male phenotypes and mating efficiency in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1983;103:43–64. doi: 10.1093/genetics/103.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kispert A, Herrmann BG, Leptin M, Reuter R. Homologs of the mouse Brachyury gene are involved in the specification of posterior terminal structures in Drosophila, Tribolium, and Locusta. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:2137–2150. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.18.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusch T, Reuter R. Functions for Drosophila brachyenteron and forkhead in mesoderm specification and cell signalling. Development. 1999;126:3991–4003. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.18.3991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C, Fire A. DNA transformation. In: Shakes D, Epstein H, editors. Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern biological analysis of an organism. London, UK: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 451–482. [Google Scholar]

- Mushegian AR, Garey JR, Martin J, Liu LX. Large-scale taxonomic profiling of eukaryotic model organisms: A comparison of orthologous proteins encoded by the human, fly, nematode, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 1998;8:590–598. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.6.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielson C. Animal evolution. Interrelationships of the living phyla. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson KJ, Cameron RA, Tagawa K, Satoh N, Davidson EH. A comparative molecular approach to mesodermal patterning in basal deuterostomes: the expression pattern of Brachyury in the enteropneust hemichordate Ptychodera flava. Development. 1999;126:85–95. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugfelder GO, Roth H, Poeck B. A homology domain shared between Drosophila optomotor-blind and mouse Brachyury is involved in DNA binding. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;186:918–925. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90833-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvkun G, Hobert O. The taxonomy of developmental control in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1998;282:2033–2041. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte-Merker S, van Eeden FJ, Halpern ME, Kimmel CB, Nüsslein-Volhard C. no tail (ntl) is the zebrafish homologue of the mouse T (Brachyury) gene. Development. 1994;120:1009–1015. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JB, Harbecke R, Kusch T, Reuter R, Lengyel JA. Drosophila brachyenteron regulates gene activity and morphogenesis in the gut. Development. 1996;122:3707–3718. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. Brachyury and the T-box genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:474–480. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— T-box genes: What they do and how they do it. Trends Genet. 1999;15:154–158. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J, Hodgkin J. Methods. In: Wood WB, editor. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. pp. 587–606. [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977;56:110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Albertson DG, Thomson JN. The Caenorhabditis elegans male: Postembryonic development of nongonadal structures. Dev Biol. 1980;78:542–576. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattler S, Russ A, Evans M, Nehls M. A combined analysis of genomic and primary protein structure defines the phylogenetic relationship of new members of the T-box family. Genomics. 1998;48:24–33. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Phil Trans Roy Soc Lond B. 1986;314:1–340. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson DG, Bhatt S, Herrmann BG. Expression pattern of the mouse T gene and its role in mesoderm formation. Nature. 1990;343:657–659. doi: 10.1038/343657a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BD. Genetic mapping with polymorphic sequence-tagged sites. In: Shakes D, Epstein H, editors. Caenorhabditis elegans: Modern biological analysis of an organism. Vol. 48. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]