The migration of health professionals, especially doctors, from the developing (third) world to the developed (first) world has caused much guilty rumination in the host countries, and lamentation in the donor countries. Accusations of immoral ‘poaching’ have been levied, non-poaching treaties have been proposed and financial compensation has been suggested as a remedy.

In all of this uproar, the doctors concerned have made sporadic attempts, in the correspondence columns of journals like the BMJ and the Lancet, to explain their decisions.1,2 Less thought has been given to the historical background, and indeed the historical inevitability, of this phenomenon.

Researching the migration motives of one group of medical migrants led me, a South African medical graduate who migrated to Australia, to consider what common factors might have led these tens of thousands of doctors to leave home and hearth, family and friends, colleagues and careers.

The colonial roots of the problem

The educational policies of the 19th century colonizing powers were mostly laudable. The major colonizers, such as Great Britain, established schools and universities in their new territories. In time, they established medical schools, training indigenous students to the same high standards as their own ‘back home’. The medical schools were staffed with expatriate lecturers, and equipment provided by the colonizing power, which also funded the research. Many ‘home’ universities bestowed their own medical degrees on the local graduates.

But then the ‘winds of change’ swept through the African and Asian colonies. With independence came the end of reliance on the colonizers. No longer did they provide the medical teachers and the equipment, nor the funds for research. The priorities of the political independence movements, and the corruption of many of the new rulers, took priority over the health of the population.

Highly trained doctors (and nurses) began to find that they could no longer practise their professions to the high standards with which they had been imbued by their expatriate teachers. As a result of regressive health policies or neglect or both, insufficient funds were available for salaries, facilities, equipment and research or because of regressive or neglected health policies. And so, coupled with a desire for a better, or at least more stable, life for their families, they began to consider emigrating to countries crying out for more doctors to meet their populations' ever-increasing demand for healthcare.

With hindsight, one could argue that the colonizers erred in training doctors instead of following the examples of Russia and China, with their feldschers and ‘barefoot doctors’. Not only would such frontline health workers have been more effective, in the long run, in caring for the health of their mainly rural populations, but their training is not recognized in other countries, ensuring that they remain at home, working in the conditions and with the people, the illnesses and the problems they know best.

Indeed, a number of former colonies have recently come to appreciate that this route will yield better results than trying to train large numbers of doctors – who would have the potential to emigrate. In Africa alone, Eritrea, Sudan, Swaziland, Uganda, Ghana and Ethiopia have now recognized their need for healthcare workers who are not trained to the high standards of European doctors.

The South African medical migrations

One of the major ‘donor’ countries, over the past 60 years, has been South Africa – but with a significant difference. Whereas the brain drain from most of the colonies has been of indigenous doctors, the South African exodus has been almost entirely of non-indigenous doctors of either European or Indian origins. Why is this so?

No country classified and categorized its people as obsessively and officially as did apartheid South Africa. Not only were people classified into ‘white’ and ‘non-white’, but into several ethnic sub-categorizations. The ‘non-whites’ included Bantu (black), ‘coloured’ (i.e. mixed racial origins), Indian, and Chinese (Japanese were ‘honorary whites’ for trading reasons). Categorization among the whites was linguistic and religious. The Afrikaans-speakers, mostly Calvinists, were distinguished from the English-speakers, who were in turn ‘clustered’ mainly into Catholic, Protestant and Jewish circles.

These categorizations determined, either legally or linguistically, each individual's medical education and, as it transpired, each individual's propensity for emigration. Non-white students could, with few exceptions, attend only the medical school at the University of Natal in Durban. Until 1966, a few were able, with a preliminary BA or BSc, to study at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits – in Johannesburg) or the University of Cape Town (UCT), the medical schools attended by whites whose first language was English. Those whose first language was Afrikaans attended mostly the medical schools in Pretoria or Stellenbosch or later in Bloemfontein, which were totally closed to non-whites.

With language went religion. The result was that Anglo-Protestant, Catholic and Jewish students mainly attended Wits or UCT. And with language and religion went politics. Wits and UCT, with their tiny numbers of non-white students, had a more liberal approach to politics, and were the seats of much anti-apartheid protest. The Afrikaans universities were the repositories of the Calvinism which justified apartheid.

All of these factors come together in the decisions of those South African medical graduates who decided to emigrate. A trickle began in 1948, after the election of a government composed of members with pro-Nazi predilections during World War II. A stream began to flow after the shootings at Sharpeville and Langa black townships in 1960. It swelled to a flood after the shooting of black school students in Soweto in 1976, ebbed and then flowed again in the mid-1980s with the states of emergency as troops fought insurgents on the borders. The flow increased following the release from jail of Nelson Mandela in 1989, when it became apparent that South Africa would be governed in future by a black majority government, and that the apartheid regime, with all its ‘white’ privileges, was doomed.

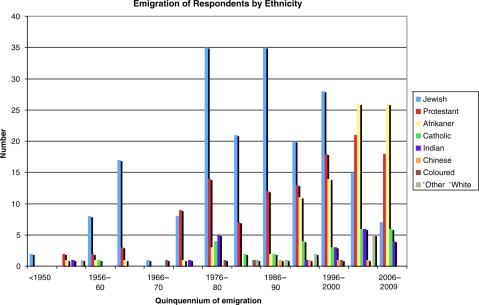

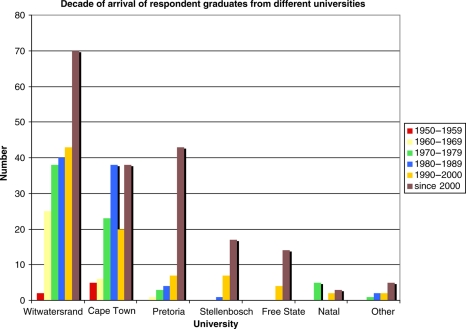

The reasons for these waves of emigration relate directly to the ethnicity of the doctors concerned (Figure 1), to their mother tongues and to the universities they attended (Figure 2). These account for most of the findings of a survey of 469 South African medical graduates, who had emigrated between 1948 and 2008.3 The respondents represented about 23% of all some 2000 migrants – a reasonable sample of the population.

Figure 1.

The ethnicity of migrants over time in relation to the date of their emigration

Figure 2.

The universities which doctors attended, in relation to the date of their emigration

Active recruitment has been the target of much criticism, with suggestions made, among other things, for host countries to deter the immigration of African-trained doctors and for the payment of compensation or an annual ‘rental’ by host countries to the countries of the doctors' origin. But there has been little success to date and little reason to believe that such a system would be practical. Money would not compensate a ‘donor’ country for its loss of skilled health personnel.

‘Agreements’ have been entered into between, for example, South Africa and some countries to limit the emigration of much-needed doctors. In 2003, a Memorandum of Understanding on ethical recruitment was entered into between the UK and South Africa. Several commentators have suggested that a possible solution might be for the host countries to train more of their own citizens, thereby diminishing their need to rely on immigrant doctors.

But whatever arguments are advanced for restricting the brain drain, strong counter-arguments are raised, including by the doctors concerned. Nothing short of draconian totalitarian measures could prevent dissatisfied doctors from emigrating.

Conclusion

South Africa ranks high among the donor countries to the medical workforces in the UK, Canada, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand and Israel. It is, of course, not alone in losing its doctors in the brain drain. Many African countries have lost between 60–80% of their doctors.4 However, South Africa, as the most economically advanced African state, has had more doctors to lose, and almost none have been indigenous Africans.

Many suggestions have been made for trying to stop the global brain drain from poor to richer, more developed countries; none has been effective. As far as the former colonial nations are concerned, it would seem that the die was cast when the colonial rulers established medical schools in their own image. It seems that nothing can now stop the flow. As for the flight of doctors from a South Africa now under black rule, current indications are that this will continue into the foreseeable future.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

PCA is the author of the book A Unique Migration: South African doctors fleeing to Australia

Funding

None

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Guarantor

PCA

Contributorship

PCA is the sole contributor

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Emeritus Professor Laurence Geffen for assistance in the preparation of this essay for publication

References

- 1.Olayemi E. Brain drain: a self-inflicted malady. BMJ 2005 July 1. See http://www.bmj.com/content/331/7507/2 .

- 2.Loeffler IJP Medical migration. Lancet 2000;356:1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold PC, Lewinsohn DE Motives for migration of South African doctors to Australia since 1948. Med J Aust 2010;192:288–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clements MA, Petterson G Medical leave: A new database of health professional emigration from Africa. Working Paper Number 95 Washington, DC: Center for Global Development, 2006 [Google Scholar]