Abstract

Mucosal surfaces are in continuous contact with microbes. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) mediate recognition of microbial molecules to eliminate pathogens. In contrast, we demonstrate here that the prominent gut commensal, Bacteroides fragilis, activates the TLR pathway on T lymphocytes to establish host-microbial symbiosis. TLR2 deletion on CD4+ T cells results in anti-microbial immune responses that reduce B. fragilis colonization of a unique mucosal niche during homeostasis. A symbiosis factor (PSA) of B. fragilis activates TLR2 directly on Foxp3+ regulatory T cells through a novel process to engender mucosal tolerance. Remarkably, B. fragilis lacking PSA is unable to restrain host immune responses and is defective in niche-specific mucosal colonization. Therefore, unlike pathogens whose TLR ligands trigger inflammation, some commensal bacteria exploit the TLR pathway to actively suppress immune reactions. We propose that the immunologic distinction between pathogens and the microbiota is mediated not solely by host mechanisms, but also through specialized molecules evolved by symbiotic bacteria that enable commensal colonization.

Microbes dominate as the most abundant life form on Earth, occupying almost every terrestrial, aquatic, and biological ecosystem on our planet. Humans are no exception. Upon birth, we are permanently colonized by countless microorganisms and throughout our lives associate with numerous additional microbes that range from those essential for health to those causing death (1). Consequently, our immune system is charged with the critical task of distinguishing between beneficial and pathogenic microbes. The human gastrointestinal tract is residence to hundreds of symbiotic bacterial species which produce myriads of molecules that our immune system immunologically tolerates (2). Simultaneously, the mucosal immune system recognizes molecular patterns from invading pathogenic bacteria to efficiently clear infections. Since symbionts and pathogens produce similar molecular patterns, the mechanism(s) for how our immune system distinguishes between the intestinal microbiota and enteric infections remain almost completely unknown.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are evolutionarily conserved molecules that promote immune responses through recognition of MAMPs (microbial-associated molecular patterns) (3). Since their discovery 2 decades ago, significant research has revealed that TLR signaling is indispensable for the proper activation of immune responses during infections. While most studies have addressed a role for TLR function by innate immune cells, it has recently been appreciated that T cells express functional TLRs (4–5). TLR2 signaling by CD4+ T cells promotes inflammatory T-helper 17 (Th17) responses (6). Furthermore, while classically thought to promote immunity, it now appears that TLR signaling on T cells can also restrain immune responses. For example, treatment of CD4+ T cell subsets with a TLR4 agonist increases anti-inflammatory activity and enhances protection from experimental colitis (7). Therefore, it appears that TLRs represent dynamic signaling systems that mediate diverse immunologic outcomes.

The intestinal microbiota is integral for human health, and Bacteroides species represent the vast majority of Gram-negative anaerobes in the human microbiota (8). The beneficial contributions of the prototypical commensal, Bacteroides fragilis, require a single immunomodulatory molecule named Polysaccharide A (PSA) which prevents and cures inflammatory disease (9–11). In this report, we explore the distinct role of PSA as an essential molecular determinant required for commensal colonization. Our findings demonstrate that PSA activation of the TLR pathway directly on Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) induces mucosal tolerance, suppresses anti-bacterial immune responses, and promotes colonization of a unique mucosal niche during homeostasis. Therefore, unlike previously studied TLR ligands of pathogens which lead to clearance of infections, PSA actually promotes microbial colonization through TLR signaling. Our studies reveal a novel receptor-ligand interaction that mediates benefits to both the host and the bacterium, and represent the first example of a molecular pathway for mutualism between microbe and mammal.

B. fragilis suppresses anti-microbial immune responses during gut colonization

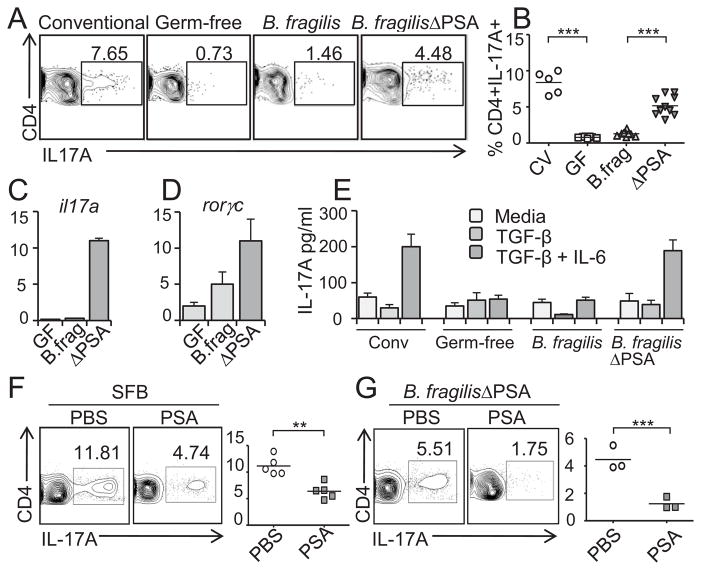

The mucosal immune system employs an arsenal of responses against enteric pathogens including Th17 cells. Intriguingly, Th17 cell development is intimately linked to the presence of the microbiota, as germ-free mice lack these cells in the small intestine and colon (refs. (12–13) and Fig. 1A). Unlike most gut microbes, segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) appear to have the unique property of inducing Th17 cells (14–15). Since most bacteria share common microbial patterns, how do other symbiotic bacteria avoid triggering intestinal immunity? Based on recent findings that specific members of the microbiota have potent immunomodulatory capacities (2), we explored the hypothesis that the prominent gut commensal Bacteroides fragilis evolved molecular mechanisms to suppress Th17 responses during homeostatic colonization. As predicted by previous studies (12, 15–16), we find that B. fragilis mono-associated animals do not appreciably induce Th17 cell development in the colon compared to germ-free controls (Fig. 1A). Remarkably however, colonization with B. fragilis in the absence of PSA (B. fragilisΔPSA) results in significant Th17 cell responses in the gut (Fig. 1A and 1B). Cells isolated from the colonic lamina propria (LP) of B. fragilisΔPSA mono-associated animals display increased secretion of IL-17A in vitro (fig. S1) and elevated transcription of il17a and rorγc, encoding for the Th17-specific lineage differentiation factor RORγt (Fig. 1C and 1D, respectively). Immune reactions were specific, as Th1 cell-associated responses were not observed during B. fragilisΔPSA colonization (fig. S2). We purified CD4+ T cells from MLNs and assayed IL-17A production during in vitro Th17 skewing assays (TCR ligation in the presence of TGF-β and IL-6) (17). Cells from B. fragilis mono-associated animals produced low levels of IL-17A, even in the presence of TGF-β and IL-6, while CD4+ T cells from B. fragilisΔPSA animals displayed elevated levels of IL-17A similar to conventionally colonized mice (Fig. 1E). We next determined whether purified PSA can suppress mucosal immunity to commensal bacteria. Oral treatment with PSA reduced Th17 cell proportions in SFB mono-associated animals (Fig. 1F). Most significantly, administration of PSA to B. fragilisΔPSA mono-associated animals greatly suppressed Th17 cell responses compared to control (PBS) treatment (Fig. 1G). These data demonstrate that unlike SFB, B. fragilis has evolved a molecular mechanism to actively restrain Th17 cell responses during homeostatic intestinal colonization.

Fig.1.

PSA actively suppresses Th17 cell development during B. fragilis colonization. (A) Colonic lamina propria lymphocytes (LPLs) were harvested and stained with anti-CD4 and IL-17A, and analyzed by flow cytometry (FC). Numbers indicate the percentage of CD4+IL-17A+ (Th17) cells. Conventional mice are specific pathogen free (SPF). (B) Compiled data from three independent experiments as in (A). CV: conventional; GF: germ-free; B.frag: B. fragilis; ΔPSA: B. fragilisΔPSA. ***p value <0.001. (C and D) CD4+ T cells were isolated from the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) of indicated animals. RNA was collected and used as a template to determine the relative levels of IL-17A (C) and RORγt (D) transcript. Error bars represent standard deviations (SD) from triplicate samples. (E) CD4+ T cells were purified from the MLNs of indicated mice and stimulated with plate bound anti-CD3 alone (light gray bars; media) or in addition to TGF-β (gray bars) or with TGF-β and IL-6 (dark gray bars). IL-17A secretion was determined by ELISA. These data are representative of three independent experiments. Error bars represent SD from triplicate samples. (F) SFB mono-associated mice were treated orally with either PBS or PSA. Colonic LPLs were isolated and the percentage of CD4+IL-17A-producing cells was determined by FC. Each symbol in the right panel represents an individual animal and shows the percentage of CD4+IL-17A+ cells. **p value <0.01. (G) B. fragilisΔPSA mono-associated mice were treated with either PBS or PSA and the LPLs were isolated and the percentage of CD4+IL-17A-producing cells was determined. Each symbol in the panel represents an individual animal. **p value <0.01.

Tregs restrain Th17 responses during B. fragilis colonization

Recent studies have shown that certain gut bacteria can promote regulatory T cell (Treg) induction (16). Furthermore, Tregs expressing the transcription factor Foxp3 (forkhead box P3) suppress pro-inflammatory Th17 cell reactions. Since B. fragilis has evolved the ability to induce anti-inflammatory gene expression from Foxp3+ Tregs in the intestine (9), we speculated Tregs may prevent immune responses during B. fragilis colonization. To test this hypothesis, germ-free RAG−/− mice (lacking T and B cells) were reconstituted with bone marrow from Foxp3-DTR donors. Under these conditions, all Foxp3-expressing Tregs also express the diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) and can be specifically ablated by administration of diphtheria toxin (DT) (18). Reconstituted mice were mono-associated with B. fragilis to induce development of Tregs (Fig. 2A). Animals were subsequently treated with DT and colonic lamina propria Treg and Th17 cell development was assessed. DT treatment of mice results in almost complete ablation of Foxp3+ T cells (Fig. 2, A and B). Interestingly, when Tregs are ablated in B. fragilis mono-associated mice, Th17 cellular responses are increased (Fig. 2, C and D and fig. S3), demonstrating that Foxp3+ Tregs are required for suppression of Th17 cells during B. fragilis colonization.

Fig. 2.

Tregs suppress Th17 responses during B. fragilis colonization. (A to D) Ablation of Tregs leads to Th17 responses during B. fragilis colonization. Germ-free RAG−/− animals were reconstituted with bone marrow from Foxp3-DTR mice and subsequently mono-associated with B. fragilis. Animals were either treated with PBS (-DT) or diphtheria toxin (+DT) as described (18). Colonic LPLs were harvested following Treg ablation, and restimulated with PMA/ionomycin and Brefeldin A. Cells were stained with anti-CD4, Foxp3, and IL-17A. (A) and (C) show FC plots for Tregs and Th17 cells. Symbols in panels (B) and (D) represent T cell proportions from individual mice within a single experiment, and are representative of two independent trials. ***p value <0.001

PSA activates CD4+ T cells via cell-intrinsic TLR signaling

PSA is an immunomodulatory bacterial molecule that shapes host immune responses (19). Induction of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and interferon-γ (IFNγ) from CD4+ T cells by PSA requires TLR2 signaling (11, 20). While TLR signaling has been predominantly studied in dendritic cells, macrophages and epithelial cells, recent evidence supports a function for TLRs by T lymphocytes (5, 21–23). We sought to determine the mechanism for how B. fragilis suppresses Th17 cell responses during colonization by testing whether PSA functions through TLR2 signaling by dendritic cells (DC) and/or CD4+ T cells. We employed an in vitro culture system using combinations of wild-type (WT) and TLR2−/− immune cells. DC-T cell co-cultures were stimulated with or without purified PSA, and secretion of IL-10 and IFNγ was determined. PSA elicits a significant increase in both IL-10 and IFNγ production when stimulating WT BMDCs and WT CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3A and fig. S4). Almost all IL-10 produced in response to PSA is derived from T cells (fig. S5). However, when TLR2−/− T cells are co-cultured with WT BMDCs, PSA-induced IL-10 production is completely lost, while IFNγ expression is not affected (Fig. 3A and fig. S4), indicating that PSA requires TLR2 expression on T cells to promote IL-10 production. Consistent with previous findings (20), pro-inflammatory IFNγ production is dependent on TLR2 signaling by DCs (fig. S4). However, when TLR2−/− DCs are co-cultured with WT CD4+ T cells, IL-10 production is completely unaffected (Fig. 3A). Therefore, unlike IFNγ responses, TLR2 expression by CD4+ T cells and not DCs is necessary for anti-inflammatory IL-10 production by PSA.

Fig. 3.

PSA directly signals through TLR2 on CD4+ T cells. (A) PSA requires TLR2 expression on T cells for IL-10 production. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) from WT or TLR2−/− animals were incubated with splenic CD4+ T cells. Co-cultures were incubated with TGF-β and anti-CD3. Levels of secreted IL-10 were determined by ELISA. Error bars represent SD from 2 independent assays performed in quadruplicate and are representative of three independent trials. ***p value <0.001, NS; not significant. (B) CD4+ T cells were isolated from wild-type (WT) and the indicated knock-out mice and cells were stimulated as in (A). IL-10 was assayed by ELISA. **p value <0.01. Error bars represent SD for quadruplicate samples and are representative of two independent trials. (C) CFSE-pulsed CD4+Foxp3− cells were cultured in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3, TGF-β, IL-6 and the indicated TLR ligands or PSA. Three days post-culture, cells were restimulated with PMA/Ionomycin and the percentage of CD4+CFSE+IL-17A+ expressing cells were determined by FC. CFSE dilution represents cell proliferation. The panel on the right summarizes data with SD from two independent trials performed in triplicate. **p value <0.01; ***p value <0.001. (D and E) PSA enhances suppressive activity of Foxp3+ Tregs directly through TLR2. CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs were purified from Foxp3EGFP mice (28) and TLR2−/− X Foxp3EGFP mice and stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and TGF-β with PSA or with indicated TLR ligands for 48 hrs. Equal numbers of live cultured Tregs were subsequently incubated with CFSE-pulsed responder cells (CD4+Foxp3−). Numbers along the bottom of (E) represent the ratio of Tregs to T effector cells. Percent (%) suppression is determined by the ratio of proliferating responder cells in each condition relative to proliferation in the absence of added Tregs. Error bars in (E) are SD from a single experiment performed in duplicate and are representative of two independent trials. (F) Purified CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs were stimulated as in (D), and qRT-PCR was performed for foxp3 and il10. Error bars are SD from a single trial in triplicate and are representative of two independent trials.

To determine whether PSA is able to induce IL-10 expression directly from T cells in the absence of antigen presenting cells (APCs), we purified CD4+ T cells and assayed IL-10 secretion. Isolated CD4+ T cells produce IL-10 in response to PSA in vitro (Fig. 3B; WT bars and fig. S6). Additionally, PSA induces IL-10 production from purified T cells in a dose-dependent manner while other TLR2 ligands do not (Pam3CysK, FSL-1, Pam2Cys K, and Zymosan) (fig. S6). TLR2 can function as either a homodimer or a heterodimer with TLR1 or TLR6 (24). We therefore tested the ability of PSA to induce IL-10 from CD4+ T cells in the absence of TLR1, TLR2, TLR6 or MyD88 (a signaling protein utilized by most TLRs). While PSA can induce high levels of IL-10 from WT CD4+ T cells, TLR1−/− and TLR6−/− CD4+ T cells, IL-10 production is lost only from TLR2−/− and MyD88−/− T cells (Fig. 3B), suggesting that PSA does not signal through TLR1/2 or TLR2/6 heterodimers. TLR2 ligands such as Pam3CysK have recently been demonstrated to induce Th17 cell development through TLR signaling on CD4+ T cells (6). To determine whether PSA has this activity, we cultured CD4+Foxp3− T cells under Th17 polarizing conditions in the presence of various TLR2 ligands (Fig. 3C). As previously reported (6), Pam3CysK induced robust Th17 development and proliferation from purified T cells; however PSA did not induce pro-inflammatory Th17 cells (Fig. 3C). These data demonstrate that PSA selectively elicits anti-inflammatory IL-10 production by signaling through TLR2 on CD4+ T cells in the absence of APCs.

TLR2 on Foxp3+ Tregs cells is required for PSA activity

To examine whether PSA directly impacts Treg function through cell-intrinsic TLR2 signaling, we treated purified CD4+Foxp3+ T cells with various TLR2 ligands. The proportion of Foxp3+ T cells was equivalent under all in vitro conditions (fig. S7). To measure Treg suppressive functions, proliferation of non-Treg responder T cells was assayed following co-culture with Tregs stimulated with media, PSA, Pam3CysK, or Pam2CysK. PSA-treated Tregs display increased suppressive capacity compared to media or other TLR2 ligand-treated Treg cultures (Fig. 3D and E). Remarkably, PSA treatment during the culture period maintained Treg activity similar to freshly isolated Foxp3+ Tregs (Fig. 3E; compare PSA to naïve). IL-2 was not produced by Tregs during treatment with any of the TLR2 ligands (data not shown), and IL-2 neutralization had no effect on in vitro suppression (fig. S8). Importantly, the suppressive capacity of PSA-treated Tregs is completely lost when Foxp3+ T cells are deficient in TLR2, indicating that PSA can uniquely induce Treg activity through TLR2 signaling (Fig. 3D and E). PSA directs the development of inducible Foxp3+ Tregs by promoting the expression of IL-10, TGF-β2 and Foxp3 (11). We show here that PSA induced these genes from purified CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs, unlike the prototypical TLR2 ligand Pam3CysK (Fig. 3F and fig. S9). PSA did not however promote anti-inflammatory gene expression from TLR2−/− Foxp3+ Tregs (Fig. 3F and fig. S9). Collectively, these studies show that unlike other TLR2 ligands, PSA potently enhances Treg function and gene expression in the absence of APCs through TLR2 signaling directly on CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells.

PSA suppresses Th17 development through CD4+ T cell-mediated TLR2 signaling

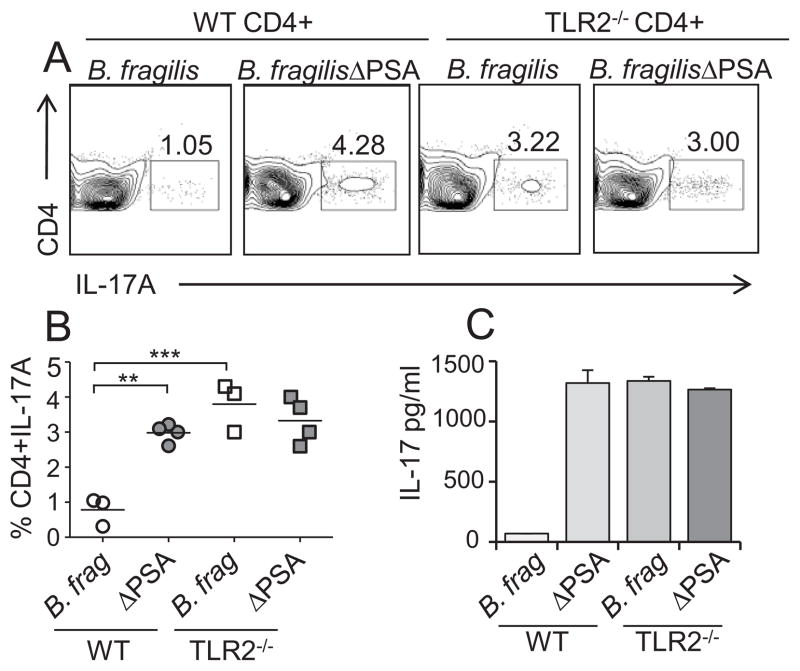

As PSA is required for suppression of Th17 cell responses in vivo, we wished to determine if PSA signals through TLR2 on Foxp3+ Tregs during B. fragilis colonization. Germ-free RAG−/− animals were reconstituted with purified CD4+ T cells from WT or TLR2−/− animals. Animals were subsequently mono-associated with either B. fragilis or B. fragilisΔPSA, and initially Treg profiles were analyzed. Unlike WT animals (TLR2 sufficient) that up-regulate IL-10 expression from Foxp3+ Tregs upon B. fragilis colonization (fig. S10 and (11)), IL-10-producing Tregs are not induced in the gut of B. fragilis mono-colonized animals lacking TLR2 on CD4+ T cells (fig. S10). We sought to determine whether TLR2 signaling on T cells is required for suppression of Th17 responses during commensal colonization. While we observed minimal Th17 cell development in WT mice mono-associated with B. fragilis, significantly increased Th17 cell responses were elicited during colonization of animals with T cell-specific TLR2 deletion (Fig. 4, A and B). Indeed, Th17 cell proportions were similar in animals colonized with B. fragilisΔPSA, regardless of whether the cells have TLR2 expression (Fig. 4, A and B). Consistent with our findings in the colon, considerably more IL-17A is produced in vitro by T cells from MLNs of mice reconstituted with TLR2-deficient T cells compared to animals containing WT CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that B. fragilis actively suppresses mucosal immunity during colonization through engagement of TLR2 directly on CD4+ T lymphocytes.

Fig. 4.

B. fragilis suppresses host Th17 cell responses through T cell intrinsic TLR2 signaling. (A and B) T cell specific TLR2 is required for the ability of PSA to suppress Th17 development. Germ-free RAG−/− animals were reconstituted with CD4+ T cells from WT or TLR2−/− mice and subsequently mono-associated with either WT B. fragilis or B. fragilisΔPSA. Colonic LPLs were isolated and analyzed for Th17 cell proportions by FC. Plots are gated on CD4+ cells. (B) Each symbol represents an individual animal. **p value <0.01; ***p value <0.001. (C) CD4+ T cells were isolated from the MLNs of indicated animals and re-stimulated with plate bound anti-CD3 in the presence of TGF-β and IL-6. IL-17A from these cultures was analyzed by ELISA. Error bars show SD from triplicate samples and are representative of two independent trials.

B. fragilis requires PSA to occupy a mucosal niche in the colon

The microbiota occupies both mucosal and luminal niches during normal colonization of the gut; however, the biogeographic distributions of specific microbial species are poorly characterized. Based on our findings, we reasoned that the functions of PSA were driven by an evolutionary impetus to prevent mucosal immune reactions against B. fragilis, thus enabling a population of bacteria to contact or associate with host tissue. We directly tested this hypothesis. When colonization levels of B. fragilis and B. fragilisΔPSA were determined by microbiological plating of feces for live bacteria, there appears to be no difference in bacterial levels in the gut lumen up to two months post-colonization (fig. S11) (19). Remarkably, we find a population of bacteria that intimately associates with intestinal crypts (Fig. 5A) and therefore in close proximity to host tissue. Whole mount preparations of medial colons were probed for bacteria following labeling with B. fragilis specific anti-sera (fig. S12). 3-dimensional reconstruction of confocal microscopic images revealed micro-colonies of B. fragilis residing within colonic crypts (Fig. 5A). The levels of B. fragilis associated with host tissue represent a fraction of total bacteria as determined by bacterial plating and qRT-PCR (Fig. 5, B and C, respectively), but likely are an important population (approximately 1 million bacteria per animal) that are in direct contact with the host immune system. We speculated that due to close proximity to host tissues, only mucosally-associated bacterial levels would be affected by the host immune responses (such as Th17 cell induction following B. fragilisΔPSA colonization). Colonization levels of B. fragilis at the mucosal surface were determined in WT B. fragilis and B. fragilisΔPSA mono-associated animals. Interestingly, animals colonized with B. fragilisΔPSA display profoundly reduced numbers of tissue-associated bacteria when compared to animals colonized with WT B. fragilis (Fig. 5D). Additionally, treatment of B. fragilisΔPSA colonized animals with purified PSA complemented this defect and increased colonization of the B. fragilisΔPSA mutant to wild-type levels (Fig. 5D). Finally, to determine B. fragilis colonization dynamics in the presence of other Th17 inducing organisms, animals that were co-associated with SFB and WT B. fragilis or B. fragilisΔPSA. Indeed, B. fragilis colonized the mucosal tissues of animals even in the presence of SFB, while the B. fragilisΔPSA mutant remained poorly associated with host tissue (Fig. 5E). Collectively, these data identify a previously unappreciated mucosal niche for B. fragilis, and reveal that PSA is required for maintaining host-bacterial symbiosis in the colon.

Fig. 5.

Mucosal colonization of B. fragilis requires suppression of host Th17 responses. (A) A population of B. fragilis is associated with the colonic mucosa. Colons from germ-free or B. fragilis mono-associated mice were fixed, stained with chicken anti-B. fragilis (green) and nuclear counterstained with DAPI (white) and imaged by whole mount confocal microscopy. Images are similar to five different z-stack images per colon, and representative of 5 mice. (B) Colon sections or luminal contents from B. fragilis mono-associated mice were homogenized and serially diluted to obtain live bacterial counts. CFUs (colony forming units) per gram of tissue were determined after microbiologic plating. Each symbol represents an individual animal. ***p value <0.001. (C) qRT-PCR analysis was performed using Bacteriodes-specific primers on RNA extracted from colon tissue or luminal contents. GF: germ-free; B.frag: B. fragilis. Error bars represent SD from individual mice in the same experiment and are representative of two independent trials. (D) qRT-PCR analysis for B. fragilis was performed on RNA extracted from colon homogenates from indicated animals. The bar furthest to the right shows colonization of B. fragilisΔPSA in animals orally treated with purified PSA. GF: germ-free; B.frag: B. fragilis; ΔPSA: B. fragilisΔPSA. Data shown for 4 animals per group, and are representative of 2 independent trials. **p value < 0.01. (E) B. fragilis is able to colonize the mucosa in the presence of other Th17 inducing organisms. Germ-free animals were colonized with SFB alone, or co-colonized with B. fragilis & SFB or B. fragilisΔPSA & SFB. RNA was extracted from colon homogenates and primers specific for Bacteroides were used to determine the relative abundance of tissue associated B. fragilis. Data shown for 4 animals per group, and are representative of 2 independent trials. *p value <0.05. (F) TLR2 deletion on CD4+ T cells leads to decreased B. fragilis mucosal colonization. Germ-free RAG−/− animals were reconstituted with TLR2−/− or WT CD4+ T cells and colonized with either WT B. fragilis or B. fragilisΔPSA. Colons were prepared and analyzed as in panel (D). **p value < 0.01. (G) Ablation of Tregs leads to decreased B. fragilis mucosal colonization. Germ-free RAG−/− animals were reconstituted with Foxp3-DTR bone and colonized. Two months post-reconstitution animals were treated with PBS (+Tregs) or with DT (-Tregs), and colons prepared as described in panel (D). **p value < 0.01. (H and I) Neutralization of IL-17A increases B. fragilis colonization. Germ-free animals were colonized with B. fragilisΔPSA and either treated with an antibody that neutralizes IL-17A (α-IL17A) or an isotype control. Colon homogenates were analyzed by live bacterial plating (H) or qRT-PCR (I) as described above. Each symbol in (H) represents an individual animal. Error bars in (I) show SD from triplicate samples and are representative of two independent trials. *p value <0.05.

PSA promotes B. fragilis colonization through TLR2

Our studies suggest that PSA induces Tregs through TLR2 signaling to suppress Th17 cell responses and promote mucosal colonization by B. fragilis. To test this model, we measured colonization levels of B. fragilis in animals with TLR2-deficiency in T cells (RAG−/− mice reconstituted with CD4+ T cells). Remarkably, when animals lack TLR2 expression on CD4+ T cells, tissue association by WT B. fragilis in the colon was reduced to the levels of B. fragilisΔPSA (Fig. 5F and fig.S13), demonstrating that TLR2 expression on T cells promotes microbial symbiosis. Accordingly, Foxp3+ Treg ablation in B. fragilis mono-associated animals resulted in significantly reduced mucosal levels of B. fragilis when compared to animals that contain Tregs (Fig. 5G). Bacterial numbers in the lumen of the gut were not altered by Treg ablation (fig. S14), showing the sensitivity of only tissue-associated bacteria to mucosal immune responses. Finally, to functionally determine the role of IL-17 responses on mucosal association, B. fragilisΔPSA mono-associated animals were treated with a neutralizing antibody to IL-17A. While levels of B. fragilisΔPSA in isotype control treated animals remained low, neutralization of IL-17A results in a 1,000-fold increase in mucosally-associated bacteria (Fig. 5, H and I). These data indicate that IL-17 suppression by PSA is a critical mechanism by which B. fragilis associates with its host. Therefore, unlike pathogens that trigger inflammatory responses through TLRs that result in immune responses to clear infections, symbiotic colonization by B. fragilis is actually enhanced by signaling via the TLR pathway promote suppression of Th17 immunity. We conclude that PSA evolved to engender host-bacterial mutualism by inducing mucosal tolerance through TLR2 activation of Treg cells.

Discussion

As the gastrointestinal tract represents a primary portal for entry by numerous pathogens, the mucosal immune system has evolved mechanisms to detect and respond to infectious agents. Toll-like receptors recognize MAMPs expressed by bacteria and coordinate a cascade of innate and adaptive immune responses that lead to clearance of intestinal pathogens (3). Accordingly, mutations in the TLR pathway result in susceptibility to viral and bacterial infections. Although TLRs have classically been studied on innate immune cells, recent reports have demonstrated expression of these pattern recognition molecules by T cells in both mice and humans (6, 22–23, 25). As bacteria contain universally conserved MAMPs, how do commensal microbes avoid triggering TLR activation unlike pathogens? It is historically believed that the microbiota is excluded from the mucosal surface (26). However, recent studies have shown that certain symbiotic bacteria tightly adhere to the intestinal mucosa (14–16), and thus immunologic ignorance may not explain why inflammation is avoided by the microbiota. Therefore, the mechanism(s) by which the immune system distinguishes between pathogens and symbionts is unknown. We report herein that the symbiosis factor of Bacteroides fragilis, PSA, can directly induce the anti-inflammatory function of Tregs by signaling directly through TLR2 on CD4+ T cells. Modulation of Treg activity by PSA restrains intestinal Th17 cell responses during commensal colonization. The functional activity of PSA on Tregs contrasts with the role of TLR2 ligands of pathogens, which elicit inflammation, and thus reveals an entirely new function for TLR signaling during homeostatic intestinal colonization by the microbiota. Paradoxically, while engagement of TLR2 by previously identified ligands is known to stimulate microbial clearance of pathogens, signaling by PSA actually allows B. fragilis persistence on mucosal surfaces. These results identify PSA as the incipient member of a new class of TLR ligands termed ‘symbiont-associated molecular patterns (SAMPs)’ that function to orchestrate immune responses to establish host-commensal symbiosis. Based on the importance of the microbiota to mammalian health (27), evolution appears to have created molecular interactions that engender immunologic tolerance to symbiotic bacteria. In summary, our findings reveal the novel paradigm that the host is not ‘hard-wired’ to intrinsically distinguish symbionts from pathogens, and microbial-derived mechanisms have evolved to actively promote mutualism between mammals and beneficial bacteria of the microbiota.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sara W. McBride and Yue Shen for help with bacterial colonization and germ-free studies. We are grateful to Dr. Alexander Y. Rudensky (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center & HHMI) for the kind gift of Foxp3-DTR mice, and Dr. Lora V. Hooper (UT Southwestern & HHMI) for germ-free Rag−/− mice. We thank members of the Mazmanian laboratory for their critical review of the manuscript. J.L.R is a Merck Fellow of the Jane Coffin Child’s Memorial Fund. S.K.M. is a Searle Scholar. Work in the laboratory of the authors is supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (DK 078938, DK 083633 & AI088626), Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America to S.K.M.

References

- 1.Ley RE, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Cell. 2006 Feb 24;124:837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009 May;9:313. doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medzhitov R. Nature. 2007 Oct 18;449:819. doi: 10.1038/nature06246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manicassamy S, Pulendran B. Semin Immunol. 2009 Aug;21:185. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukata M, et al. J Immunol. 2008 Feb 1;180:1886. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds JM, et al. Immunity. 2010 May 28;32:692. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caramalho I, et al. J Exp Med. 2003 Feb 17;197:403. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckburg PB, et al. Science. 2005 Jun 10;308:1635. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. Nature. 2008 May 29;453:620. doi: 10.1038/nature07008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ochoa-Reparaz J, et al. Mucosal Immunol. 2010 Jun 9; doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jul 6;107:12204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909122107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivanov, et al. Cell Host Microbe. 2008 Oct 16;4:337. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atarashi K, et al. Nature. 2008 Oct 9;455:808. doi: 10.1038/nature07240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, et al. Immunity. 2009 Oct 16;31:677. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivanov, et al. Cell. 2009 Oct 30;139:485. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atarashi K, et al. Science. 2011 Jan 21;331:337. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrington LE, et al. Nat Immunol. 2005 Nov;6:1123. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Nat Immunol. 2007 Feb;8:191. doi: 10.1038/ni1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. Cell. 2005 Jul 15;122:107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q, et al. J Exp Med. 2006 Dec 25;203:2853. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komai-Koma M, Jones L, Ogg GS, Xu D, Liew FY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Mar 2;101:3029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400171101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu H, Komai-Koma M, Xu D, Liew FY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 May 2;103:7048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601554103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sutmuller RP, et al. J Clin Invest. 2006 Feb;116:485. doi: 10.1172/JCI25439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babu S, Blauvelt CP, Kumaraswami V, Nutman TB. J Immunol. 2006 Apr 1;176:3885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooper LV. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009 May;7:367. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith K, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ. Semin Immunol. 2007 Apr;19:59. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin W, et al. Nat Immunol. 2007 Apr;8:359. doi: 10.1038/ni1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.