Abstract

The central enzyme in N-linked glycosylation is the oligosaccharyl transferase (OTase), which catalyzes glycan transfer from a polyprenyldiphosphate-linked carrier to select asparagines within acceptor proteins. PglB from Campylobacter jejuni is a single-subunit OTase with homology to the Stt3 subunit of the complex multimeric yeast OTase. Sequence identity between PglB and Stt3 is low (17.9%); however, both have a similar predicted architecture and contain the conserved WWDxG motif. To investigate the relationship between PglB and other Stt3 proteins, sequence analysis was performed using 28 homologs from evolutionarily distant organisms. Since detection of small conserved motifs within large membrane-associated proteins is complicated by divergent sequences surrounding the motifs, we developed a program to parse sequences according to predicted topology and then analyze topologically related regions. This approach identified three conserved motifs that served as the basis for subsequent mutagenesis and functional studies. This work reveals that several inter-transmembrane loop regions of PglB/Stt3 contain strictly conserved motifs that are essential for PglB function. The recent publication of a 3.4 Å-resolution structure of full-length C. lari OTase provides clear structural evidence that these loops play a fundamental role in catalysis The current study provides biochemical support for the role of the inter-transmembrane domain loops in OTase catalysis and demonstrates the utility of combining topology prediction and sequence analysis for exposing buried pockets of homology in large membrane proteins. The described approach allowed detection of the catalytic motifs prior to availability of structural data, and reveals additional catalytically relevant residues that are not predicted by structural data alone.

Asparagine-linked glycosylation (Ngl) is a ubiquitous, complex protein modification found in all kingdoms of life (2). The key reaction in N-linked glycosylation involves the transfer of a specific glycan to select asparagines in proteins. In eukaryotes, this glycan is later modified, abridged or extended in the ER and Golgi, resulting in a broad range of potential chemical structures. This variability accounts for the involvement of Ngl in diverse cellular functions including protein folding, cell-cell interactions, the immune response, signal transduction, and protein targeting (3-8). In humans, defects in Ngl result in a number of serious illnesses; however, the variability of disease phenotypes complicates diagnoses and hinders informative genetic screens, leaving many of these disorders ill defined (9-11). Conversely, the variable nature of Ngl makes it a useful indicator of cell state: cellular profiles and serum markers of N-glycosylation represent prospective methods for diagnosing disease states or stages of cancer progression (12, 13). N-linked glycosylation has also been implicated in infectious disease, as pathogens often exploit the pathway during infection. Ngl is frequently involved in the maturation and secretion of proteins made by intracellular pathogens; for example, glycosylation of viral envelope proteins allows many viruses to evade immune detection and invade new cells, with key examples including Influenza A and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) (14-17). The bacterial pathogen C. jejuni, a major cause of gastroenteritis, requires its innate Ngl pathway for effective colonization and invasion of host cells (18-20).

Despite its ubiquitous role in biology, studies of N-linked glycosylation have been hindered by a lack of biochemical data on key enzymes involved. Enzymes in the Ngl biosynthetic pathway tend to be either membrane-bound or associated, which can often render structural and biochemical studies challenging. The discovery of a bacterial Ngl pathway in C. jejuni provided an important model for studying the fundamental principles of the pathway (21). The Ngl pathway in C. jejuni shows broad homology to the eukaryotic pathway, which has mainly been characterized in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Both pathways involve a series of glycosyl transferases that act sequentially to afford a specific core oligosaccharide on a polyprenyldiphosphate-linked carrier. The oligosaccharide is transferred to asparagine side chains within the consensus sequence N-x-S/T, where x is any amino acid other than proline. In spite of these similarities, there are several differences between the bacterial and eukaryotic pathways: the consensus sequence in C. jejuni is slightly extended to include an acidic residue at the N -2 position (D/E-x-N-x-S/T); the core oligosaccharide in C. jejuni is composed of seven sugars (Figure 1), compared with the tetradecasaccharide common to most eukaryotes; the polyprenyl carrier in C. jejuni is undecaprenol, while in eukaryotes it is dolichol. In addition, in C. jejuni glycan assembly occurs on the periplasmic membrane as opposed to the ER membrane in eukaryotes (22).

Figure 1.

PglB-catalyzed N-linked glycosylation reaction in C. jejuni. PglB transfers the heptasaccharide GlcGalNAc5Bac (where Bac is di-N-acetyl-bacillosamine or 2,4-diacetamido-2,4,6-trideoxyglucose) from an undecaprenyldiphosphate carrier to asparagine side chains that appear in the sequon D/E-x1-N-x2-S/T, in which x1 and x2 can be any residue other than proline.

The C. jejuni OTase PglB comprises a single 82-kDa protein that shows homology to the catalytic subunit of the eukaryotic OTase, called Stt3 (23-25). PglB shares a structural organization with all Stt3 homologs, with 11-13 transmembrane domains in the N-terminal region followed by a C-terminal soluble domain. The soluble domain projects into the periplasmic space and contains the distinctive Stt3 signature motif: WWDxG, which is essential for function and is thought to play a primary role in catalysis (24). Until very recently, crystal structures existed only for the C-terminal soluble domains of PglB (C. jejuni) and the Pyrococcus furiosus Stt3; however, neither soluble domain is by itself functional, limiting the interpretability of the data (26, 27). In addition, apart from the aforementioned motif, little conservation had been clearly demonstrated between PglB and other Stt3s. The structure of the P. furiosus soluble domain shows an aspartic acid and a lysine (separated by two residues, DxxK) that appear to interact with the WWDxG motif, and mutation of these residues suggests they are also important for enzyme function (26). However, the general frequency of the DxxK pattern makes it difficult to define homologous residues in other Stt3 congeners using sequence analysis alone. A small number of other conserved regions have been suggested that showed decreased glycosylation when mutated (26-28). These studies have generated interesting hypotheses about the importance of additional regions of the OTase although the lack of quantitative biochemical studies has complicated efforts to define the role of these regions in the catalysis of glycan transfer.

Much attention has been given to the soluble domain of the Stt3 proteins, due to the fact that the highly conserved WWDxG motif is located in this region and the recent structural data from the soluble domains (26-28). Lacking, however, was a direct investigation of the biochemical significance of the transmembrane region of PglB and other Stt3 proteins, which would be predicted to be significant in catalysis due to the highly hydrophobic, and membrane-associated, undecaprenyldiphosphate-linked substrates that the OTases act upon. A simple full-length sequence alignment of several Stt3 sequences failed to expose obvious homology in the transmembrane region N-terminal to the WWDxG motif. It was hypothesized that some regions of local conservation may exist within the predicted transmembrane domains, but in general, these regions were not well defined due to the large size of the protein and the low overall sequence conservation. Therefore, to test this hypothesis, computational topology predictions were used to narrow regions of focus, for example to a specific loop between two transmembrane domains. Sequence analysis was then performed on these localized segments. To expand this analysis to a set of 28 non-redundant Stt3 sequences, which included 13 eukaryotes, 7 archaea, and 8 bacteria, a program was developed which accepts a list of homologous protein sequences and the related topology predictions. The program returns the sequence from each homolog that corresponds to a specific topological feature (e.g. the first TM sequence, or the third loop of each sequence). This method allowed topology-driven sequence analysis of a large number of Stt3 sequences, which would have been prohibitively onerous to evaluate manually.

Using this program, we were able to identify substantial homology between PglB and other Stt3s in the N-terminal transmembrane region of the protein, with several motifs that feature between the transmembrane helices showing strict conservation from bacteria to humans. To establish the functional relevance of these motifs, key residues in the motifs were mutated and the resulting proteins were recombinantly expressed in E. coli, purified as cell envelope fractions (CEFs), and subjected to kinetic analysis. Several of the mutants showed a complete loss of activity, while others showed only a partial loss. The structural integrity of the mutants relative to the wild type was probed using limited proteolysis in order to establish that the observed loss of activity for a given mutant was not the result of misfolding or large structural changes. In order to establish whether the mutations influenced the binding of the undecaprenyldiphosphate-linked glycan substrate, the effect of increasing glycosyl donor substrate concentration on catalysis was assessed. It was reasoned that the mutational effects would be most sensitive to the concentration of the glycan substrate in cases where the altered residues directly impacted interactions with this substrate. Results show that effects of certain mutations are directly correlated with substrate concentration; the effect of the mutation becomes distinctly less severe as the concentration of sugar substrate is increased. This substrate correlation provides further biochemical insight into the potential importance of these residues in the binding of the polyprenyldiphosphate-linked glycan.

Coincident with completion of these studies, a 3.4-Å resolution crystal structure was published for the PglB homolog from Campylobacter lari (1). This structure represents a remarkable leap forward in our understanding of the structure and topology of the OTases. The crystal structure provides strong evidence that the aforementioned loop motifs are critical for catalysis and enzyme activity in vivo. Our complementary biochemical evidence demonstrates the importance of the transmembrane region of PglB and indeed all Stt3 proteins for OTase function. Moreover, the utility of combining topology prediction and sequence analysis to identify conserved, functional motifs in large membrane proteins is clearly demonstrated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bioinformatic analysis

Sequences of Stt3 homologs were chosen by searching NCBI Entrez Protein Database for ‘Stt3’ and selecting Stt3 homologs from evolutionarily diverse organisms. The collated set of 28 non-redundant sequences (Supporting Information, Table S1) were subjected to topology prediction analysis via the TMHMM 2.0 server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) (29). Batch topology output was run through our ‘TMH.py’ program, which was written in Python code (provided in Supporting Information, S2). The ‘TMH’ program parsed the topology prediction data and returned output files with each Stt3 GenBank Identifier (gi) number and the predicted sequence ranges for the appropriate topological location (i.e. inside (cytoplasmic), outside, or transmembrane). Each output file and the Stt3-sequence file were directed to our ‘Extract.py’ program, which extracted the region of the sequence corresponding to the specified range indicated for a topological characteristic. The final output file for a specific topological feature showed, for each Stt3 sequence, the gi identifier followed by the sequence range and its corresponding sequence (e.g. >1322489 [1:9] MGSDRSCV \n >1322489 [100:116] ALRNWLGLPIDIRNVC, etc.). Sequence analysis was carried out by selecting a feature of each Stt3 (e.g. the first ‘inside loop’ prediction) and aligning the corresponding sequences using MAFFT (30). The alignments were used to identify conserved motifs within the given feature. The alignments were then manually adjusted for those Stt3 sequences in which the conserved motif did not appear exactly within the residue range predicted by TMHMM, but in a proximal region.

Mutant production, expression, and purification

The QuikChange (Agilent) protocol was used to generate mutations in the PglB gene, and all mutant genes were sequenced to verify specificity and accuracy of mutagenesis. All mutants and wild type PglB were expressed in a pET24a(+) vector from Novagen. All constructs were transformed into BL21-CodonPlus-RIL cells (Stratagene) and grown in 1L of culture overnight. Cell cultures were harvested by centrifugation, washed in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol), re-pelleted, and frozen at −80 °C until needed. For the preparation of Cell Envelope Fractions (CEFs), cell pellets of equal weight were resuspended in 40 mL lysis buffer with the addition of 40 μg hen egg-white lysozyme (EMD Chemicals) and 40 μL EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail III (CalBiochem). Cell suspensions were incubated at 4°C with gentle rocking for one hour and then lysed using sonication with cooling on ice. Specifically, three one-minute sets of one-second pulses at 50% amplitude, with five-minute intervals between each set were employed. Lysates were centrifuged at 6,000 x g for 30 minutes to remove insoluble debris, and the supernatant was then centrifuged at 100,000 x g for 1 hour to pellet the CEF. The resulting supernatant was discarded and the CEF was homogenized in 35 mL of high salt buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 250 mM NaCl, 250 mM KCl, 20% glycerol), incubated at 4 °C with gentle rocking for 1 hour, then pelleted again. Washed CEFs were homogenized in 10 mL of lysis buffer and stored at −80°C until further use.

For western blot analysis, 8 μL samples of CEF (diluted 1:40 in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) were mixed with 2 μL of 5X SDS reducing buffer and boiled for 5 minutes. Five μL of this solution was added to each lane of a 4-15% Tris-HCl pre-stacked gradient gel (BioRad). Gels were run at 150 volts for one hour. Protein was then transferred at 120 volts for 2 hours to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked for at least one hour in a solution of 5% BSA in TBS-T, then incubated for 1 hour in a solution of either: 1) T7 antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase diluted 1:10,000 in TBS-T (EMD4Biosciences), washed with three one-minute washes in TBS-T and a single one-minute wash in TBS and then developed using the 1-STEP BCIP/NBT (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium) developing solution (Thermo Scientific) for roughly 10 seconds or until staining became visible, at which point the nitrocellulose membrane was washed thoroughly with deionized water, or 2) Tetra His antibody, BSA-free (Qiagen) at 0.1 μg/ml in TBS-T, followed by a three one-minute washes in TBS-T, one-hour incubation in Anti-mouse alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody produced in goat (Sigma Aldrich), three one-minute washes in TBS-T and a single one-minute wash in TBS, and development with the alkaline-phosphatase substrate 1-STEP NBT/BCIP. For quantitative western blot analysis, the process was carried out similarly except with optimization of CEF dilution factor to achieve intensities in the range of those of the purified PglB. Ultimately, CEFs were diluted 1:100 and compared against a set of pure PglB internal standards, which had been quantified by measuring ultraviolet absorption at 280 nm. After staining, the nitrocellulose blots were allowed to dry for 10 minutes and then were immediately scanned at 1200 dpi and analyzed using Adobe Photoshop densitometry software. To maximize reliability, sample preparation and western blot analysis were repeated in triplicate, the data were combined and the average relative quantities used. A representative western blot and standard graph are shown in Supporting Information (Figure S6).

PglB Activity Assays

A survey of activity measurements for PglB and all PglB mutants was carried out as described previously (31). Briefly, 10 μL of DMSO was added to a tube containing 6 pmol of dried radiolabeled undecaprenyl-PP-Bac-[3H]GalNAc of specific activity 15 μCi/nmol. The tube was then vortexed and sonicated (water bath) to resuspend the substrate. Then, 100 μL of 2X assay buffer (280 mM sucrose, 2.4% Triton X-100 (v/v), and 100 mM HEPES at pH 7.5), 2 μL of 1 M MnCl2, and 5 μL of PglB CEF were added and the volume brought to a total of 190 μL with water. Reactions were initiated by the addition of 10 μL of 1 mM peptide substrate (Ac-DQNAT-p-NF-NH2; where p-NF is para-nitro-phenylalanine) dissolved in DMSO (32). Aliquots of the reaction mixture were removed at specified time intervals and quenched in 1 mL of 3:2 chloroform/methanol + 200 μL of 4 mM MgCl2. The aqueous layer was extracted, and the organic layer was washed twice with 300 μL of pure solvent upper phase (3% chloroform, 49% methanol, and 48% water with 100 mM KCl). The aqueous extracts were combined and mixed with 5 mL of EcoLite scintillation fluid (MP Biomedicals), the organic phase was mixed with 5 mL of OPTI-FLUOR scintillation fluid (Perkin Elmer), and all fractions were subjected to scintillation counting. All assays were carried out in duplicate or triplicate. For rate comparison assays at varying concentrations of sugar substrate, radiolabeled polyprenyldiphosphate-disaccharide was synthesized at specific activities of 0.15, 1.5, and 15 μCi/nmol according to procedures described previously (31). Thus, each assay (using one aliquot of polyprenyldiphosphate-linked glycan) contained the same level of tritium, but depending on the specific activity a single assay would contain 0.01, 0.1, or 1.0 μM sugar substrate.

Limited Proteolysis

Digestion profiles of wild-type PglB using trypsin, α-chymotrypsin, and proteinase K were compared, with proteinase K showing the clearest production of discrete proteolytic fragments. The incubation time, temperature, and the ratio of PglB to protease were optimized, such that the time-dependent production of discrete proteolytic fragments could be clearly viewed by applying His-tagged western blot analysis. The His-tag antibody was used because the location of the His-tag at the C-terminus of the soluble domain resulted in a more readily identifiable degradation profile. Proteolytic assays were performed at room temperature on CEF fractions that were diluted 1:40 in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5. Two μL of 0.1 mg/mL of Proteinase K (in 4 mM MgCl2) were added to 160 μL of diluted CEF. Aliquots of 20 μL were quenched into 3 μL of 100 mM PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl chloride) in ethanol, at time points of 0, 5, 10, 30, 60, and 180 minutes.

RESULTS

Predicted topologies are similar for PglB and Stt3 homologs

Topology predictions for Stt3 homologs, including PglB, indicate a conserved overall structural arrangement. Stt3 homologs share a large N-terminal multi-transmembrane domain, followed by a C-terminal soluble domain. The predicted number of transmembrane helices varies from 11-13 amongst sequences from various organisms. The topology prediction server TMHMM was used throughout the present analysis (29). Graphical depictions of predicted topologies are displayed in Figure 2 for select Stt3 homologs, chosen to represent the evolutionary diversity of the protein. Some sequences are also predicted to contain a transmembrane domain near the middle of the C-terminal soluble domain, although the majority of these are predicted to simply contain a hydrophobic region at this position. The latter scenario is almost certainly the correct one, as indicated by many studies of the soluble domain (26, 33-35). However, this discrepancy demonstrates the tentative nature of topology predictions, which often differ depending on the specific algorithm used, and thus should be used only as a guide for investigating protein topology.

Figure 2.

Sequence-based topology predictions for Stt3 homologs from archaea (M. voltae), bacteria (C. jejuni, PglB), fungi (S. cerevisiae) and a mammal (H. sapiens). The protein sequence from N-to C-terminus is represented along the x-axis, and the y-axis shows the probability that a given residue appears within a transmembrane domain or outside the membrane. The tall blocks represent predicted transmembrane domains. Predictions and illustrations were generated by the Transmembrane Hidden Markov Model (TMHMM) topology prediction program (24).

Closer inspection of the topology diagrams reveals the consistent presence of two sizeable loops (> 40 residues) located in similar regions of each of the Stt3 topology predictions. One loop of roughly 50 residues appears consistently after the first transmembrane domain; a second loop of roughly 40 residues appears 2-3 transmembrane domains before the start of the soluble domain (Figure 2). Investigation of the sequences corresponding to the first loop reveals a prominently conserved aspartic acid (residue D54 in PglB). While other groups have suggested the existence of conserved residues, a systematic investigation of potential regions of conservation or their functional significance has not been previously carried out (28, 34). Indeed, such investigations are hindered by the difficulty of detecting small motifs within the context of the large and variable full-length sequence. Utilizing the conserved topology of Stt3 homologs, sequences corresponding to a specific topological feature of each Stt3 protein were extracted, and then sequence analysis was confined to these sections. To systematize the approach, a computer program was developed to automatically extract the sequence corresponding to a given topological feature for a series of 28 divergent Stt3 homologs (see Methods).

Identification of conserved motifs

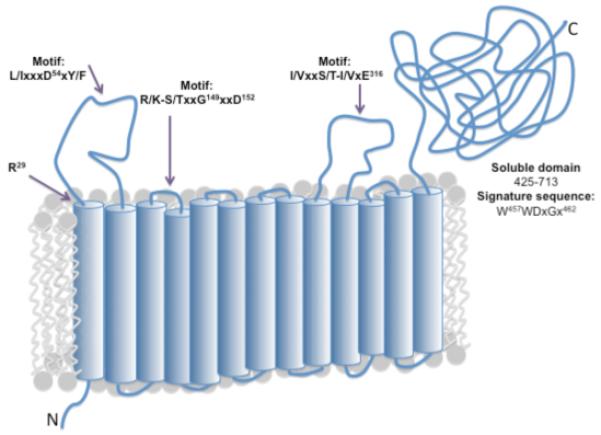

The sequence analysis revealed strong conservation in several Stt3 inter-TM loops, which is not easily detected when the full-length Stt3 sequences are aligned. Abbreviated alignments of these motifs are shown for PglB (C. jejuni) and other key Stt3 homologs in Figure 3. Full alignments can be found in Supporting Information (Figure S3). The first transmembrane helix contains a conserved arginine residue (residue R29 in PglB). The first loop (which would appear in the lumen in eukaryotic Stt3s and the periplasm of the C. jejuni PglB) contains the [L/I]xx[D54]x[Y/F] motif. The third loop, which would be in the ER lumen or the periplasm contains the [R/K][S/T]xx[G149]xx[D152] motif, and the seventh loop contains the [I/V]xxx[S/T][I/V]x[E316] motif. A topology model, shown in Figure 4, was constructed based on a combination of topology predictions for Stt3 homologs and the conserved motifs, and is used to indicate the locations of the identified motifs.

Figure 3.

Alignments of conserved residues and motifs shown in a selection of representative sequences. Full alignments with all analyzed sequences can be found in the Supporting Information (Figure S3). Top left alignment shows a conserved arginine within the first transmembrane domain. The corresponding residue number in PglB (C. jejuni) is designated in superscript. Alignments and conservation histograms shown were made using Jalview multiple alignment editor. (doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033). Histogram shading: light to dark designates most to least conserved.

Figure 4.

Topology model of PglB showing locations of conserved motifs. Model is based on a combination of topology prediction programs (see Methods) and conservation of loop regions, and agrees with topology of the C. lari crystal structure. Thirteen transmembrane helices are followed by a globular domain located in the periplasm. Predicted locations of identified motifs are indicated by arrows. The N-terminus is located in the cytoplasm.

Mutation and kinetic characterization of residues in conserved motifs

In order to investigate the importance of the three motifs in catalysis, site-directed mutagenesis was performed on several conserved residues in PglB. As negative controls, residues (K124 and K351) that would be predicted to appear in non-conserved loop regions were also mutated (Figure 4). All candidate residues were mutated to alanine, and each acidic residue was additionally mutated to its amide-containing complement (Asn for Asp, Gln for Glu), and/or its acidic complement residue (Asp for Glu, or vice versa).

In addition, we investigated the proposal that a DxxK motif is required for OT catalysis (26). The crystal structure of the soluble domain of P. furiosus Stt3 suggests a role for an aspartic acid and a lysine, separated by two residues, fifty residues C-terminal to the signature WWDxG motif; when mutated, a decrease in OTase activity was previously observed (26). Given the natural frequency of the aspartic acid and lysine residues and thus the DxxK pattern within the PglB sequence, it is difficult to surmise functionally equivalent residues in other Stt3 sequences. PglB has three appearances of DxxK in the C-terminal soluble domain: D475xxK478, D519xxK522, and D553xxK556. To establish whether a functionally conserved DxxK motif exists in PglB, each aspartic acid and lysine within these DxxKs were mutated to alanine and analyzed along with the loop mutations.

All mutants were overexpressed in E. coli, as described in Methods. A wild type (WT) PglB strain and a strain containing the empty expression vector (referred to as the ‘blank’) served as the positive and negative controls, respectively. All mutants and WT were expressed with an N-terminal T7-tag and a C-terminal His10-tag. A semi-pure CEF was prepared for each culture, and a fraction of each mutant CEF was run on a western blot alongside the WT and blank. Immunostaining with the anti-His and anti-T7 antibodies confirmed comparable expression levels of PglB in the fractions assayed, and also expression of the full-length protein (Figure 5A). Ideally, each mutant enzyme would be purified to homogeneity for quantification; however, the unstable nature of membrane proteins upon solubilization and purification can result in a source of error with unpredictable effects on activity measurements. Thus, it was considered preferable to use the mutant and wild-type enzymes in the more stable cell envelope fractions and to establish similar enzyme concentrations by using western blot analysis.

Figure 5.

A. Western blot analyses showing comparable levels of PglB wild type and mutants in the cell envelope fractions (CEFs). Each blot included a negative control (‘Blank CEF’) and a positive wild-type PglB control. Western blots were visualized using the anti-tetra-His antibody (which recognizes the C-terminal His10 tag of each mutant) as well as the T7-tag antibody (which recognizes the N-terminal T7 tag of each protein). B. PglB mutants maintain wild-type tertiary structure, as shown by limited proteolysis. A representative western blot showing a typical PglB degradation profile is shown. Lane 1 shows molecular weight standards with benchmark bands labeled to left of blot (kDa). Anti-His western blot analysis was performed on fractions of the proteolysis reaction quenched at 0, 5, 10, 30, 60, and 180 minutes (lanes 2-7). Arrow indicates the location of the full-length PglB band at the start of the reaction. Images of blots for all mutants can be found in Supporting Information (Figure S5).

The activities of PglB and each of the mutants were measured using a radioactivity-based assay, which measures transfer of a radiolabeled glycan from the undecaprenyldiphosphate carrier to a peptide bearing the PglB consensus sequence (see Methods). Results from activity assays for PglB enzymes with mutations in conserved loop motifs and the first DxxK motif are shown in Figure 6. Results from activity assays for mutants with wild-type levels of activity can be found in Supporting Information (Figure S4), along with extended time points for loop mutants. Mutant activity results are summarized in Table 1. Mutants were divided into broad categories based on relative activity level, as follows: WT-level activity (+++), decreased activity (++), activity detectable only with overnight incubation (+), or no detected activity (−).

Figure 6.

PglB activity assays performed on CEFs of inter-transmembrane domain loop mutants. Each assay set included a negative control (‘Blank CEF’) and a positive PglB control (WT). Each plot indicates the mutants assayed in the legend. Shown here are those with mutations in the conserved loop motifs and the D475xxK motif. Assay results for negative-control mutants (K124A and K351A) and additional DxxK motifs are shown in Supporting Information (Figure S4).

Table 1.

Relative activity levels of all PglB mutants tested. Each mutant is listed along with its predicted location. Activity levels are considered null (−) if no activity is seen over the blank CEF background, +++ if levels are comparable to wild type (WT), ++ if levels are distinctly lower than WT, and + if levels are detected only with overnight incubation times.

| Mutant | Location | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| WT | − − − | +++ |

| Blank CEF | − − − | − |

| R29A | between TM domains 1 & 2 | − |

| D54A | between TM domains 1 & 2 | − |

| D54E | between TM domains 1 & 2 | − |

| D54N | between TM domains 1 & 2 | − |

| K124A | between TM domains 2 & 3 | +++ |

| R145A | between TM domains 3 & 4 | + |

| D152A | between TM domains 3 & 4 | − |

| D152E | between TM domains 3 & 4 | ++ |

| E316A | between TM domains 7 & 8 | + |

| E316D | between TM domains 7 & 8 | ++ |

| E316Q | between TM domains 7 & 8 | − |

| K351A | between TM domains 10 & 11 | +++ |

| D475A | soluble domain | ++ |

| D475E | soluble domain | ++ |

| K478A | soluble domain | ++ |

| D519A | soluble domain | +++ |

| K522A | soluble domain | +++ |

| D553A | soluble domain | +++ |

| K556A | soluble domain | +++ |

Mutants maintain tertiary structure

In order to establish that the PglB mutations do not cause activity loss by disrupting folding, mutants that showed a decrease or loss in activity were analyzed by limited proteolysis. Figure 5B shows a western blot representative of the wild-type degradation profile. Before protease is added (time 0) the bands of the major digestion products are already visible at very low levels, perhaps due to endogenous E. coli protease activity. Over time, individual bands appear or change in intensity to give a characteristic profile, which was used to establish structural integrity in mutants with loss of activity. All mutants display similar degradation profiles to the wild-type protein. Blots for all assayed mutants can be found in Supporting Figure S5.

Correlation of mutation effects with concentration of Und-PP-disaccharide substrate

It was determined that the effect of mutants D152E, E316D, and D475A and D475E are inversely correlated with concentration of Und-PP-glycan substrate: at increasing substrate concentrations, the mutant rates approached the wild-type rate (Figure 7). Initial mutant enzyme assays (Figure 6) were performed in the presence of saturating peptide substrate (50 x apparent KM) and a relatively low concentration of radiolabeled disaccharide substrate (0.01x apparent KM), which causes the measured rates to be highly sensitive to changes in binding efficiency of undecaprenyldiphosphate-disaccharide and insensitive to changes in peptide binding. The initial assay was constructed in this manner to test the hypothesis that the conserved loop motifs, given the acidic nature of many key residues, might be involved in metal-ion mediated binding of the diphosphate in the glycosyl donor substrate since PglB is known to require divalent cations (generally Mn(II) or Mg(II)) for activity. Then, in order to establish whether the mutations influenced the binding of the undecaprenyldiphosphate-linked glycan, we assessed the effect of increasing glycosyl donor substrate concentration on catalysis. The initial rates for these mutants were measured at three separate concentrations of this substrate: 0.01, 0.1, and 1.0 μM (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Average initial rates for low-activity PglB mutants assayed at three concentrations of polyprenyldiphosphate disaccharide substrate (0.01, 0.1, and 1.0 μM). Percent of WT rate for each mutant is determined at each concentration, with the average rate of WT set to 100%. Inset: magnification of R145A, D152E, and E316A values for clarity. Rate values shown are corrected for small variations in concentration, as determined by quantitative western blot analysis. Raw rate data can be found in the Supporting Information (Table S7).

Initial western blot analyses ensured that a similar level of each PglB construct was expressed, providing a level of confidence such that mutants could be reliably grouped into broad categories based on activity levels (Table 1). However, to further characterize the partially active mutants by directly comparing initial turnover rates, a more precise western blotting method was used to quantify relative levels of protein (see Methods). It was determined that levels of all mutants were very similar, with a maximum concentration difference of +1.7-fold relative to WT (Supporting Figure S6). The relative levels of each mutant in CEF measured by western blot analyses were reproducible, allowing us to determine and correct for any effects on rate comparisons.

DISCUSSION

Interpretation of PglB mutants in context of kinetic and structural data

The bioinformatic and biochemical data that we report can now be framed in the context of the recent structure analysis of the Stt3 homolog from C. lari, also designated as PglB (1). In this structure, the conserved acidic residues in each loop motif (D56, D154, and E319 of the C. lari PglB) are proposed to form a pocket that accommodates a divalent magnesium cation and the nucleophilic asparagine. The essentiality of these residues is supported by use of an in vivo glycosylation assay, which exploits the gel shift observed upon glycosylation.

The biochemical results that we present provide a more detailed characterization of the residues implicated by the structure, and additionally expose critical residues that are not made evident by the structural data. The aspartic acid in the [L/I]xx[D54]x[Y/F] motif (D54) can be set apart from the other two implicated acidic residues (D152 and E316) by the in vitro activity measurements. In particular, D152 and E316 can both be mutated to their acidic counterparts (D152E and E316D) and still retain activity, albeit at a notably decreased level. This indicates the primary role that the negative charge plays at these sites, as the alanine mutations at these sites show minimal activity, and E316Q showed no activity. In contrast, with D54, we observe that when mutated to alanine, asparagine, or glutamic acid, activity is completely eliminated. This establishes D54 as highly specific for its role in function with respect to both charge and size and suggest a pivotal role in catalysis.

It is also observed that the effects of certain mutations can be directly correlated with substrate concentration; the effect of the mutation becomes less pronounced as the concentration of the glycosyl donor substrate is increased. For example, this is observed with D152E and E316D (Figure 7). For other mutations, including D54 and K478A the increased Und-PP-Bac-GalNAc substrate concentration had little effect. This substrate correlation analysis suggests that these residues are implicated in the binding of the polyprenyldiphosphate-linked glycan. This trend is consistent with the reported structure data showing these residues coordinating the divalent cation, and the hypothesis that the divalent cation is further involved in coordinating the disphosphate of the glycan substrate. Further biochemical analyses using more complex glycosyl donor substrates may help determine the relative effect of the mutations on substrate binding and catalysis.

With respect to the [R/K][S/T]xx[G149]xx[D152] motif, we find that R145 and D152, when individually mutated to alanine, lead to an almost complete loss of PglB activity. Mutation of D152 to a glutamate restores partial activity. In this context, a fundamental role for the aspartic acid at the +2 position to the D152 (D154 in C. jejuni PglB, D156 in C. lari PglB) has been proposed (1). Specifically, this pair of aspartic acids is proposed to represent a ‘DxD’ motif that is characteristic in the glycosyltransferase superfamily GT-C (1, 36, 37). However, the alignments derived from our topology-guided motif analysis suggest that the sequence characteristics in this region of the OTase are not definitively conserved across evolution. Indeed, it is evident from our alignment of the motif (Figure 3, Supporting Figure S3) that the residue +2 to the defined motif is a glutamic acid in almost fifty percent of homologs examined, and this residue is a proline in the seven archaeal homologs that were analyzed in this study. Site-directed mutagenesis data are not yet available to evaluate the kinetic significance of the second aspartic acid in the DxD motif in PglB and the natural frequency of the generic and variable motif leaves significant room for further exploration. Therefore the association with the characteristic GT-C superfamily motif may not be clear.

Interestingly, the arginine (R29) in C. jejuni PglB that appears in the first transmembrane helix, is also conserved and essential: when mutated to alanine, activity is eliminated. In view of this data alone, the role that this arginine may play in PglB function is not clear. However, when the equivalent residue (R31) is examined in the C. lari structure one observes that this arginine side chain appears to be in direct contact with threonine 148 (or T146 in C. jejuni PglB). In this context, we note that this position is highly conserved as a hydroxyamino acid (either a serine or threonine) throughout our 28 examined Stt3 homologs and appears in the [R/K][S/T]xx[G149]xx[D152] motif in the third transmembrane loop (Figure 4). This apparent interaction again highlights the unique ability of this topology-guided sequence analysis to reveal residues key to enzyme function. The high conservation of this hydroxyamino acid and its apparent interaction with the essential arginine in the first transmembrane helix allows us to propose that these residues may be involved in mediating in a conformational shift of the enzyme, as the interaction represents a clear link between the catalytic site and an integral membrane helix. In the future, it will be very interesting to gain a structural analysis of other substrate-bound forms of the enzyme to determine the likelihood of this scenario.

Interpretation of DxxK mutants in context of kinetic and structural data

Of the three appearances of DxxK sequon in the PglB soluble domain, mutations in D475 and K478 negatively impacted PglB activity, while [D519xxK522]and [D553xxK556] alanine mutants showed levels comparable to wild type (Supporting Figure S4). The effect on D475A was more significant than that on K478A (Figure 6), which calls the proposed DxxK motif into question. Considering the enhanced impact of D475A relative to K478A, and the additional fact that this aspartic acid is highly conserved throughout all OTases while the lysine is not (Figure 3), it appears that a ‘DxxK motif’ is not playing an essential role in OTase activity. However, the high level of conservation of D475 and the clear impact of the mutation on activity indicates that this residue is likely involved the OTase function. Interestingly, an increase in the concentration of the polyprenyldisphosphate glycan in the assay steadily attenuated the effect of D475A and D475E on activity, while no such trend is seen for K478A (Figure 7). As in the case of D152 and E316, this trend suggests that mutation at these sites affects the ability of PglB to bind the polyprenyldiphosphate glycan substrate.

Mutants maintain tertiary structure

Limited proteolysis represents powerful tool for identifying flexible, exposed regions of proteins and for studying how tertiary structure (and thus susceptibility to proteolysis) is affected by mutations, substrate presence and many other factors (38-42). Mutants that showed a decrease or loss in activity were analyzed by limited proteolysis to establish that activity loss is not due to misfolding (see Methods), and all mutants assayed display similar degradation profiles to the wild-type protein (Figure 5B, Supporting Figure S5). In addition to reinforcing that the mutants that are analyzed are properly folded, it was of interest to determine the precise location of proteolysis. The three major C-terminal degradation products appear at roughly 50, 30, and 23 kDa, which provides a rough approximation of the cut site. To further narrow the location of the proteolysis sites, N-terminal Edman degradation sequencing of the digestion bands was performed. Using the N-terminal sequencing data and the estimated molecular weights of the fragments, it was determined that the enzyme was being cut at G331/S332 and Y467/S468, yielding C-terminal fragments of 45.5 and 29.3 kDa, respectively.

The structure of the C. lari PglB puts this observation in a structural context and correlates susceptibility to proteolysis with the proposed flexibility and exposure of these regions (1). The first proteolysis site appears just after the exposed loop 5, designated as EL5, which is noted as highly disordered in the C. lari structure (1). The second site occurs just after the WWDxG motif, in a coil connecting two helices. Interestingly, while both of these sites appear in coils adjacent to catalytically important sites, neither site appears prominently exposed in the crystal structure. Nonetheless, the dramatic preference for these proteolysis sites is shown clearly by the discrete banding pattern indicated by western blot. Thus, it is possible that these sites become exposed in an alternate conformation of PglB, which may provide insight into structural changes implicated in substrate binding and release. Indeed, it was proposed that this conformational change would involve movement of EL5 (1). Also, the striking conservation of the WWDxG motif, combined with its proximity to a preferential proteolytic cut site, may indicate that this helix is involved in this conformational change, in addition to the proposed role in peptide/protein substrate binding (1).

CONCLUSIONS

In recent years, it has become abundantly clear that the conserved loop segments between transmembrane domains often play a fundamental role in substrate recognition and/or catalysis (43-46). However, it is particularly difficult to observe sequence conservation in these regions because motifs may be embedded within transmembrane regions that have diverged considerably, thereby complicating sequence alignments. Demonstrated here is a straightforward method for defining these buried regions of conservation applied to the complex integral-membrane OTase PglB. Topology predictions are generated for a list of homologous sequences using freely available software; a designed algorithm then parses each sequence by topological feature. These sequence segments are then more fruitful for detecting regions of conservation through sequence alignment. The systematic nature of the method allows for position-specific sequence analysis of a large number of divergent sequences of a given protein, which is crucial for determining the extent and significance of proposed motifs. These results expose the extraordinary level of conservation that exists in Stt3 homologs from bacteria through humans. Conservation over this evolutionary span implies that these regions play an essential role in the OTase activity. The biochemical data verifies that in PglB, many of these residues are essential for enzyme activity, and through limited proteolysis experiments it is shown that activity loss in mutated PglB is not caused by major structural changes. These combined data indicate a direct involvement of these motifs in protein function.

The recent publication of a medium-resolution structure of the C. lari PglB indicates that these motifs are centrally involved in catalysis (1). Thus, the structural data, combined with the independently acquired alignments and biochemical data, provide compelling evidence for the roles of these motifs in OTase catalysis. Much biochemical work remains to investigate the details of the catalysis. In this context, the limited proteolysis approach will be useful for ascertaining whether the E5 loop is flexible in the presence, as well as the absence, of each substrate, and thus may provide insight into the dynamics of these regions accompanying substrate binding, catalysis, and substrate release. Ultimately, similar studies on eukaryotic OTases will be essential for relating the prokaryotic OTase studies to OTase catalysis universally.

While the structural studies now provide an excellent framework for developing new experiments to investigate N-linked glycosylation, the importance of quantitative, in vitro biochemical assays with defined quantities of pure substrates and precise measurements of enzymatic rates, cannot be overstated. Recently, based on the C. lari PglB crystal structure a mechanism for nucleophilic activation of the asparagine nitrogen has been proposed (1). A challenge in the future will be to acquire structural and biochemical data that are complementary and consistent with specific mechanistic proposals. Currently, the structural data provides valuable information on the residues that are likely to be involved in catalysis, however at the present structural resolution of 3.4 Å, it is not feasible to identify specific hydrogen bonding networks or, distinguish between the nitrogen and carbonyl oxygen of the nucleophilic asparagine amide. Furthermore, due to the crystallization conditions, the C. lari PglB structure was acquired at a pH of 9.4, where activity is very low (47). Lastly, the site of polyprenyldiphosphate-glycan substrate binding, the order of binding and release of substrates and products, and the nature of potential conformational changes, remain to be assessed. These data will be required to enable the development of hypotheses concerning the mechanistic details of the reaction. The structural and biochemical data, when in agreement, will provide an important foundation for unraveling the details of this intricate cellular process, which has eluded geneticists, biochemists, and microbiologists alike for so long.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr. Angelyn Larkin for providing selected soluble domain mutants and members of the Imperiali group for assistance with materials as well as valuable discussions.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by NIH Grant GM039334 (to BI).

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- Ngl

asparagine-linked glycosylation

- OTase

oligosaccharyl transferase

- TM

transmembrane

- CEF

cell envelope fraction

- gi

GenBank Identifier

- TMHMM

TM Hidden Markov Model

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- Ac

acetyl

- Bac

N,N-diacetyl-bacillosamine

- GalNAc

N-acetyl-galactosamine

- Glc

glucose

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- pNF

para-nitrophenylalanine

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION A list of sequences used in alignments and code for sequence analysis and full alignments of STT3 motifs. Quantitative western blot and proteolysis analysis data. Additional activity assays performed on of PglB mutants. Supporting materials (S1-S7) can be found free of charge online at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lizak C, Gerber S, Numao S, Aebi M, Locher KP. X-ray structure of a bacterial oligosaccharyltransferase. Nature. 2011;474:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larkin A, Imperiali B. The expanding horizons of asparagine-linked glycosylation. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4411–4426. doi: 10.1021/bi200346n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fares F. The role of O-linked and N-linked oligosaccharides on the structure-function of glycoprotein hormones: development of agonists and antagonists. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760:560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helenius A, Aebi M. Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:1019–1049. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janik ME, Litynska A, Vereecken P. Cell migration-the role of integrin glycosylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:545–555. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitra N, Sinha S, Ramya TN, Surolia A. N-linked oligosaccharides as outfitters for glycoprotein folding, form and function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudd PM, Woods RJ, Wormald MR, Opdenakker G, Downing AK, Campbell ID, Dwek RA. The effects of variable glycosylation on the functional activities of ribonuclease, plasminogen and tissue plasminogen activator. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1248:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)00230-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J, White AL. Role of N-linked glycans, chaperone interactions and proteasomes in the intracellular targeting of apolipoprotein(a) Biochem Soc Trans. 1999;27:453–458. doi: 10.1042/bst0270453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeze HH. Update and perspectives on congenital disorders of glycosylation. Glycobiology. 2001;11:129R–143R. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeze HH. Human disorders in N-glycosylation and animal models. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1573:388–393. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schachter H, Freeze HH. Glycosylation diseases: quo vadis? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:925–930. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnold JN, Saldova R, Hamid UM, Rudd PM. Evaluation of the serum N- linked glycome for the diagnosis of cancer and chronic inflammation. Proteomics. 2008;8:3284–3293. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potapenko IO, Haakensen VD, Luders T, Helland A, Bukholm I, Sorlie T, Kristensen VN, Lingjaerde OC, Borresen-Dale AL. Glycan gene expression signatures in normal and malignant breast tissue; possible role in diagnosis and progression. Mol Oncol. 2010;4:98–118. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sayce AC, Miller JL, Zitzmann N. Targeting a host process as an antiviral approach against dengue virus. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vigerust DJ, Shepherd VL. Virus glycosylation: role in virulence and immune interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Komarova NL, Nowak MA, Hahn BH, Kwong PD, Shaw GM. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422:307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skehel JJ, Stevens DJ, Daniels RS, Douglas AR, Knossow M, Wilson IA, Wiley DC. A carbohydrate side chain on hemagglutinins of Hong Kong influenza viruses inhibits recognition by a monoclonal antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:1779–1783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.6.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacon DJ, Szymanski CM, Burr DH, Silver RP, Alm RA, Guerry P. A phase-variable capsule is involved in virulence of Campylobacter jejuni 81-176. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:769–777. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerry P, Szymanski CM, Prendergast MM, Hickey TE, Ewing CP, Pattarini DL, Moran AP. Phase variation of Campylobacter jejuni 81-176 lipooligosaccharide affects ganglioside mimicry and invasiveness in vitro. Infect Immun. 2002;70:787–793. doi: 10.1128/iai.70.2.787-793.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szymanski CM, Burr DH, Guerry P. Campylobacter protein glycosylation affects host cell interactions. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2242–2244. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2242-2244.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szymanski CM, Yao R, Ewing CP, Trust TJ, Guerry P. Evidence for a system of general protein glycosylation in Campylobacter jejuni. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:1022–1030. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weerapana E, Imperiali B. Asparagine-linked protein glycosylation: from eukaryotic to prokaryotic systems. Glycobiology. 2006;16:91R–101R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen MM, Weerapana E, Ciepichal E, Stupak J, Reid CW, Swiezewska E, Imperiali B. Polyisoprenol specificity in the Campylobacter jejuni N-linked glycosylation pathway. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14342–14348. doi: 10.1021/bi701956x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan Q, Lennarz WJ. Studies on the function of oligosaccharyl transferase subunits. Stt3p is directly involved in the glycosylation process. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47692–47700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young NM, Brisson JR, Kelly J, Watson DC, Tessier L, Lanthier PH, Jarrell HC, Cadotte N, St Michael F, Aberg E, Szymanski CM. Structure of the N-linked glycan present on multiple glycoproteins in the Gram-negative bacterium, Campylobacter jejuni. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42530–42539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Igura M, Maita N, Kamishikiryo J, Yamada M, Obita T, Maenaka K, Kohda D. Structure-guided identification of a new catalytic motif of oligosaccharyltransferase. EMBO J. 2008;27:234–243. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maita N, Nyirenda J, Igura M, Kamishikiryo J, Kohda D. Comparative structural biology of eubacterial and archaeal oligosaccharyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:4941–4950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Igura M, Kohda D. Selective control of oligosaccharide transfer efficiency for the N-glycosylation sequon by a point mutation in oligosaccharyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13255–13260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.213900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glover KJ, Weerapana E, Numao S, Imperiali B. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of glycopeptides with PglB, a bacterial oligosaccharyl transferase from Campylobacter jejuni. Chem Biol. 2005;12:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen MM, Glover KJ, Imperiali B. From peptide to protein: comparative analysis of the substrate specificity of N-linked glycosylation in C. jejuni. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5579–5585. doi: 10.1021/bi602633n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karamyshev AL, Kelleher DJ, Gilmore R, Johnson AE, von Heijne G, Nilsson I. Mapping the interaction of the Stt3 subunit of the oligosaccharyl transferase complex with nascent polypeptide chains. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40489–40493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim H, von Heijne G, Nilsson I. Membrane topology of the Stt3 subunit of the oligosaccharyl transferase complex. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20261–20267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nilsson I, Kelleher DJ, Miao Y, Shao Y, Kreibich G, Gilmore R, von Heijne G, Johnson AE. Photocross-linking of nascent chains to the Stt3 subunit of the oligosaccharyltransferase complex. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:715–725. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maeda Y, Watanabe R, Harris CL, Hong Y, Ohishi K, Kinoshita K, Kinoshita T. PIG-M transfers the first mannose to glycosylphosphatidylinositol on the lumenal side of the ER. EMBO J. 2001;20:250–261. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Mushegian A. Three monophyletic superfamilies account for the majority of the known glycosyltransferases. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1418–1431. doi: 10.1110/ps.0302103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leandro J, Leandro P, Flatmark T. Heterotetrameric forms of human phenylalanine hydroxylase: Co-expression of wild-type and mutant forms in a bicistronic system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:602–612. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vita C, Dalzoppo D, Fontana A. Limited proteolysis of thermolysin by subtilisin: isolation and characterization of a partially active enzyme derivative. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1798–1806. doi: 10.1021/bi00328a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spolaore B, Bermejo R, Zambonin M, Fontana A. Protein interactions leading to conformational changes monitored by limited proteolysis: apo form and fragments of horse cytochrome c. Biochemistry. 2001;40:9460–9468. doi: 10.1021/bi010582c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fontana A, de Laureto PP, Spolaore B, Frare E, Picotti P, Zambonin M. Probing protein structure by limited proteolysis. Acta Biochim Pol. 2004;51:299–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spolaore B, Polverino de Laureto P, Zambonin M, Fontana A. Limited proteolysis of human growth hormone at low pH: isolation, characterization, and complementation of the two biologically relevant fragments 1-44 and 45-191. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6576–6586. doi: 10.1021/bi049491g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashkenazi A, Viard M, Wexler-Cohen Y, Blumenthal R, Shai Y. Viral envelope protein folding and membrane hemifusion are enhanced by the conserved loop region of HIV-1 gp41. FASEB J. 2011 doi: 10.1096/fj.10-175752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Estrada-Mondragon A, Reyes-Ruiz JM, Martinez-Torres A, Miledi R. Structure-function study of the fourth transmembrane segment of the GABArho1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17780–17784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012540107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCracken LM, McCracken ML, Gong DH, Trudell JR, Harris RA. Linking of Glycine Receptor Transmembrane Segments Three and Four Allows Assignment of Intrasubunit-Facing Residues. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2010;1:482. doi: 10.1021/cn100019g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ponsaerts R, De Vuyst E, Retamal M, D’Hondt C, Vermeire D, Wang N, De Smedt H, Zimmermann P, Himpens B, Vereecke J, Leybaert L, Bultynck G. Intramolecular loop/tail interactions are essential for connexin 43-hemichannel activity. FASEB J. 2010;24:4378–4395. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-153007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma CB, Lehle L, Tanner W. N-Glycosylation of yeast proteins. Characterization of the solubilized oligosaccharyl transferase. Eur J Biochem. 1981;116:101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.