Abstract

Background. Candidemia is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients or patients undergoing invasive treatments. Dectin-1 is the main β-glucan receptor, and patients with a complete deficiency of either dectin-1 or its adaptor molecule CARD9 display persistent mucosal infections with Candida albicans. The role of genetic variation of DECTIN-1 and CARD9 genes on the susceptibility to candidemia is unknown.

Methods. We assessed whether genetic variation in the genes encoding dectin-1 and CARD9 influence the susceptibility to candidemia and/or the clinical course of the infection in a large cohort of American and Dutch candidemia patients (n = 331) and noninfected matched controls (n = 351). Furthermore, functional studies have been performed to assess the effect of the DECTIN-1 and CARD9 genetic variants on cytokine production in vitro and in vivo in the infected patients.

Results. No significant association between the single-nucleotide polymorphisms DECTIN-1 Y238X and CARD9 S12N and the prevalence of candidemia was found, despite the association of the DECTIN-1 238X allele with impaired in vitro and in vivo cytokine production.

Conclusions. Whereas the dectin-1/CARD9 signaling pathway is nonredundant in mucosal immunity to C. albicans, a partial deficiency of β-glucan recognition has a minor impact on susceptibility to candidemia.

In developed countries, candidemia is one of the most prevalent bloodstream infections in hospital settings and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Candidemia is a systemic infection with Candida spp, predominantly Candida albicans, that occurs mostly in patients that are immunocompromised due to neutropenia, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, or invasive surgery, or by total parenteral nutrition [1, 2]. The first line of defense against fungal infections is the innate immune system that initiates recognition and initial elimination of pathogens, and subsequently induces the activation of adaptive immunity. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are expressed by innate immune cells, and they specifically recognize moieties expressed on the surface of the microbial pathogens, designated as PAMPs (pathogen-associated molecular patterns) [3].

The recognition of PAMPs relies on several families of PRRs, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and RIG-I helicases, all acting in concert to activate downstream signaling in innate immune cells, thereby inducing production of proinflammatory cytokines and activation of T-cell responses [4]. In the case of fungal pathogens, it is especially TLRs and CLRs that mediate recognition [3]. Among the PRRs recognizing C. albicans, the archetypal CLR dectin-1 detects β-glucans [5–8], which comprise 40% of the total cell wall of C. albicans. Upon β-glucan recognition, intracellular signaling is induced involving the adaptor proteins spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and CARD9 (caspase recruitment domain family member 9), as well as Bcl-10 and Malt1, ultimately activating the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) [7, 9]. The dectin-1 receptor is expressed mainly by cells of the myeloid lineage (monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils) [7, 10].

Previously, we described a Dutch family with members suffering from onycomycosis and recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, in which genetic studies have demonstrated that the presence of an early stop mutation in the DECTIN-1 gene led to a partial or total deficiency in β–glucan recognition [11]. This genetic defect resulted in impaired recognition of C. albicans and decreased cytokine production by immune cells, especially for cytokines involved in the T-helper (Th) 17 pathway [11]. The support for the hypothesis of an important role of dectin-1 recognition for mucosal anti-Candida defense was provided by the description of another family with a defective CARD9 gene. Interestingly, family members with CARD9 deficiency exhibited a similar clinical phenotype with predominantly recurrent mucocutaneous Candida infections. Nonfunctional CARD9 was also associated with defects in Th17 responses [12]. Of note, patients with nonfunctional dectin-1 appeared not to be predisposed to invasive Candida infection, whereas CARD9-deficient patients were severely prone to develop invasive Candida infections, especially in the brain [11, 12].

These studies implicate the dectin-1/CARD9 pathway as nonredundant in mucosal host defense against C. albicans. However, the role of the dectin-1/CARD9 innate pathway for the host defense against systemic Candida infections has not been directly investigated, although it would be expected to be less important. In the present study, a cohort of patients with candidemia has been studied for the potential association of susceptibility to candidemia with genetic variation in the DECTIN-1 and CARD9 genes. The early stop codon mutation in the DECTIN-1 gene that was previously characterized in the Dutch family described above is a polymorphism with a general allele frequency of 6%–8% in Caucasian populations and 4% in African populations. This polymorphism, which clearly affects dectin-1 function, could therefore be studied as a population-wide potential determinant in susceptibility to candidemia. In contrast, the mutation in the CARD9 gene causing CARD9 deficiency is a very rare mutation, which until now was only found in 1 family [12]. Alternatively, a common genetic variation in the coding region of the CARD9 gene has been detected with a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at amino acid position 12. This nonsynonymous SNP leads to an amino acid substitution from a serine to an asparagine residue. Because of its potential to influence CARD9 function and high minor allele frequency in both Caucasian (53%) and African (25%) populations, this SNP was also selected in this genetic study [13]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine whether these DECTIN-1 and CARD9 SNPs influence susceptibility to candidemia.

PATIENTS, MATERIALS, AND METHODS

Patients

Patients were enrolled after informed consent (or waiver as approved by the institutional review board) at the Duke University Hospital (DUMC, Durham, North Carolina) and Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center (RUNMC, Nijmegen, the Netherlands). The study was approved by the institutional review boards at each study center, and enrollment occurred between January 2003 and January 2009. The clinical characteristics of the patients, both infected and noninfected, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics for DUMC Infected Cohort (n = 291) and Control Cohort (n = 300), Including Caucasian and African-American Adult Patients

| Variable | Infected cohort | Control cohort |

| Mean age (y) | 55.9 | 57.8 |

| Immunocompromised state | 59% | 38% |

| HSCT | 1% | 0% |

| Solid organ transplant | 12% | 2% |

| Active malignancya | 32% | 20% |

| Solid yumor | 23% | 12% |

| Leukemia | 7% | 5% |

| Lymphoma | 4% | 4% |

| Chemotherapy within past 3 mo | 17% | 11% |

| Neutropenia (ANC <500 cells/mm3) | 10% | 4% |

| HIV-infected | 2% | 0.1% |

| Surgery within past 30 d | 43% | 48% |

| Receipt of total parenteral nutrition | 19% | 4% |

| Dialysis dependent | 12% | 7% |

| Acute renal failure | 34% | 22% |

| Liver failure | 25% | 4% |

| Intensive care unit admission within past 14 d | 49% | 34% |

| Bacteremia within past 48 h | 24% | 2% |

| Median baseline serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.3 | 1.0 |

| Median baseline WBC count (cells/mm3) | 10.55 | 8.55 |

| Candida sppb | ||

| albicans | 42% | ... |

| glabrata | 29% | |

| parapsilosis | 16% | |

| tropicalis | 13% | |

| krusei | 4% | |

| Other Candida spp | 3% | |

NOTE. ANC, absolute neutrophil count; DUMC, Duke University Hospital; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; WBC, white blood cell.

Subjects could have >1 species isolated.

Sixteen subjects had >1 species isolated.

To be included in the analysis of susceptibility to infection, infected subjects must have had at least 1 positive blood culture for a Candida species while hospitalized at the participating center. Noninfected controls must have been hospitalized with no history or evidence of candidemia/invasive candidiasis or any invasive fungal infection. Noninfected controls were recruited from the same hospital wards as infected patients so that comorbidities and clinical risk factors for infection would be similar between groups. Intergroup comparisons between the 2 groups of noninfected subjects and between the 2 groups of infected subjects (at DUMC and RUNMC) were performed regarding similarity in genetic distribution of the studied SNPs prior to further statistical analysis of infected versus noninfected subjects. Subjects were excluded from the study if insufficient volume of blood or clinical data were available to allow for analysis.

Genetic Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood using standard procedures. Genotyping for the DECTIN-1 Y238X (c.714T > G, rs16910526) and CARD9 S12N (c.35G > A, rs4077515) polymorphisms was performed by using the TaqMan single-nucleotide assay C_33748481_10 and C_25956930_20, respectively, on the 7300 ABI real-time polymerase chain reaction system (all from Applied Biosystems).

Genetic Association With Clinical Outcomes

Due to the lack of detailed clinical data on the Dutch candidemia patients (n = 40) and controls (n = 51) recruited at RUNMC, the correlations of the genetic data with clinical outcome were performed with the North American patients (n = 291) and controls (n = 300) from DUMC only. Infected subjects at DUMC were followed prospectively for up to 12 weeks following diagnosis of candidemia to determine clinical outcome: (1) disseminated disease, (2) persistent fungemia, and (3) all-cause mortality at 30 days. Disseminated infection was defined as the presence of Candida spp at normally sterile body sites outside the bloodstream (excluding the urine). Persistent fungemia was defined as ≥5 days of persistently positive blood cultures. This analysis was performed in the entire infected cohort, as the progression of the disease once occurring is not expected to differ between European and African-American patients, and race was considered a covariate in the analysis. Variables with P value <.2 were further assessed in a multivariable logistic regression model. Variables with P < .05 were retained in the final predictive model. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were reported for variables that remained significant in the final multivariable model.

Cytokine Stimulation Assays

PBMCs were isolated from healthy volunteers by Ficoll-Paque gradient. Subsequently, stimulation with heat-killed C. albicans was performed for 24 hours, 48 hours, or 7 days. The stimulation time varied for each cytokine, being 24 hours for tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α, interleukin (IL)–1β, IL-6, and IL-8, 48 hours for interferon (IFN)–γ, and 7 days for IL-17 production. For the 7-day culture, the medium was supplemented with 10% human serum. After the incubation time, the above-mentioned cytokines were measured in the supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (purchased from R&D Systems or Sanquin Research).

Serum Cytokine Measurements

Cytokine concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, and IFN-γ in plasma and serum samples obtained from infected patients from day 1 up to day 5 after initial positive blood culture were measured by multiplex fluorescent bead immunoassay (xMAP technology, Bio-Rad) and a BioPlex microbead analyzer (Luminex) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Bioinformatic Analysis

In order to predict the effect on the conformation of the CARD9 protein given the S12N amino acid change, we used HOPE (http://www.cmbi.ru.nl/hope/), a web server that performs automatic mutant analysis. No homology model was produced because no template with enough identity to the CARD9 sequence exists [14]. We also used the Polyphen software in order to determine quantitatively the damage for the protein stability taking into account the amino acid change of the CARD9 SNP [15].

Statistical Analysis

For the analysis of SNPs, statistical comparisons of frequencies were made between infected versus noninfected subjects and of clinical parameters within the infected group using the χ2 test with SPSS version 16.0 software. Data were analyzed for Caucasian descendents separately from African-Americans, as allelic frequencies were expected to differ between these 2 populations. For the analysis of the in vitro PBMC stimulation and in vivo serum cytokine measurements, a Mann–Whitney U test was performed on the DECTIN-1 genotype experiment and a Kruskal–Wallis 1-way analysis of variance was performed on the CARD9 genotype experiment with the use of GraphPad Prism software version 4.00.

RESULTS

Genetic Analysis

Data from adult patients (n = 331 [291 North American and 40 Dutch]) and controls (n = 351 [300 North American, 51 Dutch]) were included in the analysis for genetic association with susceptibility to infection. Data from children were excluded from this analysis because the number of children enrolled (n = 27) was insufficient to analyze this association extensively in a pediatric population, where factors relating to susceptibility to candidemia may differ from those for adults.

The intergroup comparison between the Dutch RUNMC and North American Caucasian DUMC noninfected controls and between the infected subjects recruited at DUMC and RUNMC revealed a similar genetic distribution of the genotyped SNPs, which allowed the groups to be merged into 1 group of noninfected controls and 1 group of infected subjects (data not shown). In contrast, the African-American patients from the DUMC cohort displayed a different genetic pattern, and they were analyzed separately. Genetic distribution of the DECTIN-1 Y238X and CARD9 S12N polymorphisms in the studied patient groups is shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The genotyping of candidemia patients and noninfected matched controls for polymorphisms in DECTIN-1 and CARD9 revealed no significant association with susceptibility to candidemia. After statistical analysis of the Dutch and the North American cohorts separately, again no significant differences were obtained (data not shown). Similarly, no differences were observed when data were analyzed separately in nonneutropenic and neutropenic patients (data not shown). A post hoc analysis of power for the dectin-1 polymorphism demonstrated that we had 86.7% power to detect a 10% difference in frequency in the Caucasian cohort, with 238 infected and 263 non infected subjects, with a 2-sided α = .05. For African-Americans, a post hoc analysis of power for dectin-1 polymorphism demonstrated that we had 76% power to detect a 10% difference in frequency, with 93 infected and 88 noninfected subjects, also with a 2-sided α = .05.

Table 2.

Frequencies of the Genotype of the DECTIN-1 Early Stop Polymorphism Y238X and the Incidence of Candidemia in African-American and Caucasian Patients

| TT (%) | TG (%) | GG (%) | P valuea | ||

| African-American | Noninfected (n = 88) | 95.5 | 4.5 | 0 | .515 |

| Infected (n = 93) | 97.1 | 2.9 | 0 | ||

| Caucasian | Noninfected (n = 263) | 83.4 | 16.6 | 0 | .624 |

| Infected (n = 238) | 83.9 | 15.7 | 0.4 |

P values were calculated with the χ2 test.

Table 3.

Frequencies of the Genotype of the CARD9 Ser12Asn Polymorphism and the Incidence of Candidemia in African-American and Caucasian Patients

| GG (%) | GA (%) | AA (%) | P valuea | ||

| African-American | Noninfected (n = 88) | 44.2 | 50.7 | 5.2 | .305 |

| Infected (n = 93) | 49.5 | 40.8 | 9.7 | ||

| Caucasian | Noninfected (n = 263) | 34.1 | 48.3 | 17.6 | .413 |

| Infected (n = 238) | 40.3 | 43.0 | 16.7 |

P values were calculated with the χ2 test.

In order to study the role of these genetic variants in the clinical outcome of candidemia, clinical parameters on dissemination, persistence, and 30-day mortality of infected patients were correlated with the DECTIN-1 and CARD9 genotype. Because these data were only available for the North American cohort, for these analyses the Dutch patients were excluded. No significant associations between DECTIN-1 and CARD9 polymorphisms and clinical parameters were observed in these analyses (Table 4). Minor differences in the clinical characteristics of the control and candidemia groups have been observed. Although we cannot completely rule out that these differences might have caused the lack of effect of the polymorphisms, from the clinical point of view these differences were not as big as to expect major effects.

Table 4.

Univariate Analysis of the Association Between the DECTIN-1 and CARD9 Polymorphisms With Disseminated Disease, Persistent Fungemia, and 30-day Mortality in the DUMC Infected Cohort (n = 291)

| Genotype | DECTIN-1 Y238X | CARD9 S12N |

| No disseminated disease (n = 268) | 11.6% | 56.9% |

| Disseminated disease (n = 63) | 15.0% | 61.5% |

| P valuea | .46 | .54 |

| No persistent fungemia (n = 280) | 12.1% | 56.6% |

| Persistent fungemia (n = 51) | 12.8% | 64.3% |

| P valuea | .90 | .35 |

| Survivors (n = 238) | 13.4% | 56.8% |

| Nonsurvivors (n = 93) | 9.0% | 60.0% |

| P valuea | .29 | .61 |

NOTE. Numbers are the percentages of patients with each outcome who were found to bear the mutant allele of the particular polymorphism.

P values were calculated with the χ2 test.

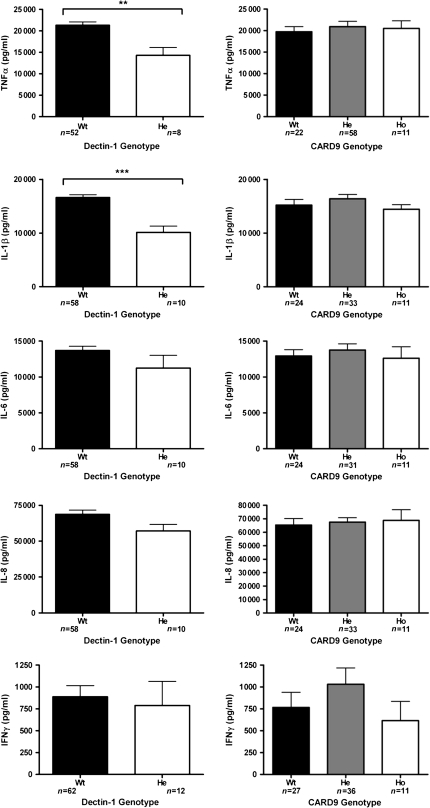

Functional Analysis of Cytokine Profiles

In order to assess the functional consequences of the SNPs in DECTIN-1 and CARD9, both in vitro and in vivo cytokine measurements were performed. The in vitro evaluation was performed by measuring cytokine production upon heat-killed Candida stimulation of PBMCs with different DECTIN-1 and CARD9 genotypes, obtained from healthy volunteers. The results of these in vitro assays are shown in Figure 1. Significant differences in cytokine production were observed between cells obtained from individuals with different DECTIN-1 genotypes, including decreased production of TNF-α (P = .003) and IL-1β (P < .0001), while differences in the production of IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ (Figure 1), and IL-17 (data not shown) were not statistically significant. In contrast, no effect of the CARD9 polymorphism on C. albicans–induced cytokine production was apparent.

Figure 1.

Functional analysis on the stimulation of the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with heat-killed Candida albicans blastoconidia. Cytokine production capacity of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukin (IL)–1β, IL-6, IL-8, and interferon (IFN)-γ was compared between the cells obtained from healthy volunteers bearing wild-type or variant DECTIN-1 or CARD9 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). He, heterozygous; Ho, homozygous; Wt, wild type. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 (Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis 1-way analysis of variance).

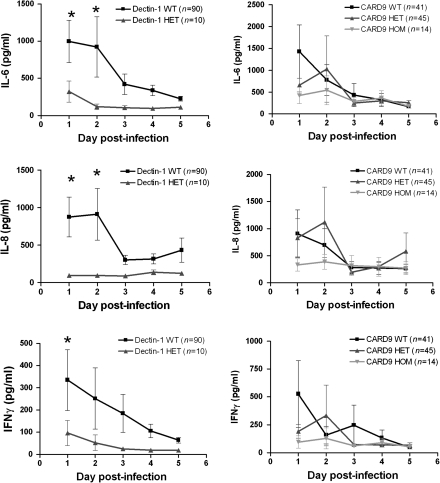

Serum samples collected from infected patients during the first 5 days after initial positive blood culture were measured for concentrations of IL-6, IL-8, and IFN-γ (Figure 2). In general, the IL-6, IL-8, and IFN-γ production decreased over time. Correlation with the genotype of the patients revealed that patients heterozygous for the DECTIN-1 polymorphism had lower cytokine concentrations at the initiation of infection, which remained low throughout the follow-up period. No differences in cytokine-circulating concentrations were apparent between individuals bearing different CARD9 genotypes.

Figure 2.

Cytokine concentrations of interleukin (IL)–6, IL-8, and interferon (IFN)-γ in plasma and serum samples obtained from infected patients from day 1 up to day 5 after initial positive blood culture correlated with the DECTIN-1 or CARD9 genotype. HET, heterozygous. HOM, homozygous; WT, wild type. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 (Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis 1-way analysis of variance).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we assessed the influence of genetic polymorphisms in the genes encoding dectin-1 and CARD9 for susceptibility to candidemia. Patients heterozygous for the DECTIN-1 Y238X polymorphism exhibited moderately lower cytokine responses compared with individuals bearing wild-type DECTIN-1 genotypes, whereas no effects of the CARD9 SNP on these responses were observed. Despite these differences, the genetic variation in DECTIN-1 and CARD9 was not associated with susceptibility to candidemia.

Polymorphisms in several PRRs have been suggested to be associated with a higher risk to fungal infections [16–19]. Recent studies have unveiled genetic variants of DECTIN-1 and CARD9 that predispose to mucocutaneous fungal infections [11, 12]. Individuals heterozygous for the DECTIN-1 Y238X allele have also been shown to display increased colonization with Candida when they suffer from hematological malignancies, leading to more frequent prescription of prophylactic antifungal therapy [20]. However, the role of genetic variability in these genes in susceptibility to candidemia was not known. Therefore, we have investigated whether SNPs in DECTIN-1 and CARD9 are associated with susceptibility to systemic Candida infection.

Dectin-1 is the most important receptor of β–glucans, and it plays an important role for induction of cytokines in human monocytes and macrophages [21, 22]. The DECTIN-1 Y238X polymorphism, the best characterized of the 2 SNPs analyzed in this study, clearly affects dectin-1 function [11], as confirmed by the in vitro cytokine data provided here. However, our data indicate that if patients are heterozygous for this DECTIN-1 polymorphism, neither susceptibility to Candida bloodstream infections, nor clinical parameters such as severity and dissemination of the infection or 30-day mortality, are affected. This might be due to the specific involvement of dectin-1 recognition pathway in mucosal immunity to C. albicans, reflected by the induction of cytokines that are crucial for Th17 responses, including IL-6 and IL-17. In contrast, for an effective immune response to prevent Candida bloodstream infections, proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, or Th1 responses releasing IL-18 and IFN-γ, may play a more important role. Indeed, the production of proinflammatory cytokines after stimulation of cells in vitro with C. albicans was only moderately decreased in individuals heterozygous for the DECTIN-1 Y238X SNP, and these data are supported by cytokine stimulation experiments from individuals with complete dectin-1 deficiency [11]. Unexpectedly, serum cytokine measurements of IFN-γ were found to be lower in patients heterozygous for the DECTIN-1 Y238X polymorphism, although this genetic variant does not seem to confer an additional risk to develop or worsen the outcome of candidemia. Presumably, the relatively high residual circulating cytokine concentrations in individuals bearing the DECTIN-1 polymorphism were sufficient to afford protection against candidemia. It can be therefore concluded that other PRRs and mechanisms of antifungal host defense can compensate for the deficit of dectin-1 function, especially at the tissue level where Candida invasion takes place.

Several explanations are possible for why no association of the CARD9 S12N SNP with susceptibility to candidemia was observed. Because the consequences of the presence of the CARD9 polymorphism for its function have not been studied, one possibility is that this polymorphism only minimally affects the protein structure. A bioinformatic approach may assess the putative effect on the function of the molecule of the amino acid change from serine to asparagine in CARD9. Since in the Protein Data Bank there is no 3-dimensional model of the CARD9 protein available, as well as no modeling template to build a homology model, the analysis was made by comparing the amino acid composition of the protein bearing the mutation with the wild-type protein with the Swift Yasara twinset via the HOPE server [14]. This analysis generated evidence that the amino acid change is important because the mutation is located on position 12 in the CARD domain. These domains occur in a wide range of proteins and are thought to mediate the formation of larger protein complexes via direct interactions between individual CARDs. Moreover, as serine and asparagine differ in size and hydrophobicity and the mutated residue is buried in the core of the protein, this change may also modify CARD9 function. Nevertheless, the Swift algorithm predicted that the polymorphism S12N is “allowed” [23], and the Polyphen algorithm predicts the effect of the serine to asparagine amino acid change as “benign” for protein function, taking into account that this residue position is not conserved through evolution [15], and this is supported by the lack of differences in cytokine production.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that genetic variations in SNPs of the dectin-1/CARD9 pathway have no major impact on the susceptibility to systemic infections with C. albicans. The dectin-1/CARD9 recognition pathway seems therefore to be of high importance for mucosal antifungal host defense, whereas systemic immunity to Candida largely relies on alternative immune recognition pathways.

Funding

This work was partially supported by a Vici grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research to M. G. N, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI-51537 to M. D. J. and AI-73896 to J. R. P.). D. C. R. was funded by the European Commission through the FINSysB Marie Curie Initial Training Network (PITN-GA-2008-214004).

Acknowledgments

All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Perlroth J, Choi B, Spellberg B. Nosocomial fungal infections: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Med Mycol. 2007;45:321–46. doi: 10.1080/13693780701218689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spellberg B. Novel insights into disseminated candidiasis: pathogenesis research and clinical experience converge. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Netea MG, Brown GD, Kullberg BJ, Gow NA. An integrated model of the recognition of Candida albicans by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:67–78. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:135–45. doi: 10.1038/35100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown GD, Gordon S. Immune recognition. A new receptor for beta-glucans. Nature. 2001;413:36–7. doi: 10.1038/35092620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown GD, Herre J, Williams DL, Willment JA, Marshall AS, Gordon S. Dectin-1 mediates the biological effects of beta-glucans. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1119–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown GD. Dectin-1: a signalling non-TLR pattern-recognition receptor. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:33–43. doi: 10.1038/nri1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gantner BN, Simmons RM, Canavera SJ, Akira S, Underhill DM. Collaborative induction of inflammatory responses by dectin-1 and Toll-like receptor 2. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1107–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross O, Gewies A, Finger K, et al. Card9 controls a non-TLR signalling pathway for innate anti-fungal immunity. Nature. 2006;442:651–6. doi: 10.1038/nature04926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid DM, Gow NA, Brown GD. Pattern recognition: recent insights from dectin-1. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferwerda B, Ferwerda G, Plantinga TS, et al. Human dectin-1 deficiency and mucocutaneous fungal infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1760–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glocker EO, Hennigs A, Nabavi M, et al. A homozygous CARD9 mutation in a family with susceptibility to fungal infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1727–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frazer KA, Ballinger DG, Cox DR, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–61. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venselaar H, Te Beek TA, Kuipers RK, Hekkelman ML, Vriend G. Protein structure analysis of mutations causing inheritable diseases. An e-Science approach with life scientist friendly interfaces. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:548. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramensky V, Bork P, Sunyaev S. Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3894–900. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bochud PY, Chien JW, Marr KA, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphisms and aspergillosis in stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1766–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carvalho A, Pasqualotto AC, Pitzurra L, Romani L, Denning DW, Rodrigues F. Polymorphisms in toll-like receptor genes and susceptibility to pulmonary aspergillosis. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:618–21. doi: 10.1086/526500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Graaf CA, Netea MG, Morre SA, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 Asp299Gly/Thr399Ile polymorphisms are a risk factor for Candida bloodstream infection. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woehrle T, Du W, Goetz A, et al. Pathogen specific cytokine release reveals an effect of TLR2 Arg753Gln during Candida sepsis in humans. Cytokine. 2008;41:322–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plantinga TS, van der Velden WJ, Ferwerda B, et al. Early. stop polymorphism in human DECTIN-1 is associated with increased candida colonization in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:724–32. doi: 10.1086/604714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gow NA, Netea MG, Munro CA, et al. Immune recognition of Candida albicans beta-glucan by dectin-1. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1565–71. doi: 10.1086/523110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Netea MG, Gow NA, Munro CA, et al. Immune sensing of Candida albicans requires cooperative recognition of mannans and glucans by lectin and Toll-like receptors. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1642–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI27114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vriend G. WHAT IF: a molecular modeling and drug design program. J Mol Graph. 1990;8:52–6. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(90)80070-v. 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]