Abstract

Background: Sagopilone (ZK 219477), a lipophylic and synthetic analog of epothilone B, that crosses the blood–brain barrier has demonstrated preclinical activity in glioma models.

Patients and methods: Patients with first recurrence/progression of glioblastoma were eligible for this early phase II and pharmacokinetic study exploring single-agent sagopilone (16 mg/m2 over 3 h every 21 days). Primary end point was a composite of either tumor response or being alive and progression free at 6 months. Overall survival, toxicity and safety and pharmacokinetics were secondary end points.

Results: Thirty-eight (evaluable 37) patients were included. Treatment was well tolerated, and neuropathy occurred in 46% patients [mild (grade 1) : 32%]. No objective responses were seen. The progression-free survival (PFS) rate at 6 months was 6.7% [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.3–18.7], the median PFS was just over 6 weeks, and the median overall survival was 7.6 months (95% CI 5.3–12.3), with a 1-year survival rate of 31.6% (95% CI 17.7–46.4). Maximum plasma concentrations were reached at the end of the 3-h infusion, with rapid declines within 30 min after termination.

Conclusions: No evidence of relevant clinical antitumor activity against recurrent glioblastoma could be detected. Sagopilone was well tolerated, and moderate-to-severe peripheral neuropathy was observed in despite prolonged administration.

Keywords: chemotherapy, glioblastoma, phase II trial, recurrent disease, sagopilone

introduction

Despite recent progress with combined chemoradiotherapy, glioblastoma—the most frequent and most malignant form of primary brain tumors in adults—almost invariably recurs [1, 2]. Treatment options for recurrent tumors are limited and depend on the type of initial first-line therapy, the disease- or progression-free interval, tumor size and location and the patient’s general condition. Repeat surgery may be considered for resectable tumors exerting a mass effect [3], while for smaller tumors, re-irradiation is increasingly being considered. Independent of these local treatments, additional systemic therapy is indicated. Among agents with some established, albeit limited, activity are temozolomide [4] and the nitrosoureas lomustine and fotemustine [5–7] and carboplatin [8]. However, single-agent response rates are usually below 10%, with up to 20%–30% of patients still free from progression at 6 months. The rate of patients being alive and progression free at 6 months (PFS6) has been established as a reproducible surrogate end point [9].

New and active agents against recurrent glioblastoma are urgently needed, and a number of classic cytotoxic and targeted agents have been evaluated in this setting. Most recently, bevacizumab has raised a lot of enthusiasm in the treatment of recurrent glioma with reported response rates of 25%–40%; however, whether this translates into substantial prolongation of survival remains to be demonstrated [10, 11].

Sagopilone (ZK 219477), fully synthetic analog of epothilone B, inhibits microtubule depolarization, thus blocking the cell cycle in the G2/M phase and inducing apoptosis [12]. This mechanism of action is similar to that of taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel). In contrast to taxanes, however, some epothilones including sagopilone retain activity also against multidrug-resistant tumors. ZK 219477 is not recognized by cellular efflux mechanisms (ABC transporter) [13], and it crosses the blood–brain barrier [14, 15].

In nude mice, sagopilone almost completely prevented the growth of orthotopically implanted human glioma (U373, U87) or breast cancer cell lines (brain metastases model) [14, 16].

The toxicity profile of ZK 219477, as emerging from phase I studies, basically consists of peripheral sensory neuropathy, mild nausea/vomiting, arthralgia, myalgia, diarrhea, fatigue, alopecia as well as leucopenia and anemia. Peripheral neuropathy, a toxicity common to tubulin-targeting agents, is expected to be the most clinically relevant toxicity of ZK 219477 [17, 18].

Since ZK 219477 crosses the blood–brain barrier, the occurrence of central nervous system toxicity may occur. Two cases of ataxia of central nervous origin were observed at the highest administered, and the maximum tolerated, dose, within a phase I study, but not at doses of up to 16.4 mg/m2 [17].

Maximum concentrations of sagopilone are reached at the end of the intravenous infusion, with rapid distribution into tissues within minutes translating in a prolonged terminal half-life of 2–3 days. The predominant route of sagopilone elimination is via biliary/fecal excretion of metabolites (Bayer Schering Pharma, data on file).

In a small exploratory trial, prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival was suggested in younger patients with heavily pretreated glioblastoma or anaplastic astrocytoma [19].

patients and methods

study design and patient selection

This concerns a one-stage early phase II and pharmacokinetic study exploring single-agent activity of sagopilone in glioblastoma patients at first progression. The study was developed, conducted and analyzed by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC; protocol #26061), in collaboration with Bayer Schering Pharma. Eligible patients were adults (>18 years) with a histologically proven glioblastoma according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification. The tumor must have recurred or progressed after primary therapy [either combined chemoradiotherapy or one line of chemotherapy in case of multifocal disease not amenable to radiotherapy (RT)]. Recurrence must be evaluable and bidimensionally measurable on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with a minimum of 2 cm for the largest diameter. No prior chemotherapy for recurrent disease was allowed. Patients requiring enzyme-inducing antiepileptic therapy were excluded or had to be switched to alternative anticonvulsive therapy, with a washout period of >1 month. Patients had to be on a stable or decreasing dose of corticosteroids for at least 1 week before registration. Other eligibility criteria included a WHO performance status of 0–2, an interval since the end of RT of at least 3 months, no prior high-dose RT >65 Gy (or target lesion outside the RT field), normal hematological function (neutrophils ≥1.5 × 109 cells/l, platelets ≥100 × 109 cells/l) and adequate hepatic [bilirubin <1.5 × upper limit of the normal (ULN) range, alkaline phosphatase and transaminases (ASAT–ALAT) <2.5 times ULN] and renal function (serum creatinine <1.5 ULN). Surgery for recurrent disease was not allowed, unless residual measurable disease was documented by postoperative MRI or computed tomography within <72 h.

All patients gave written informed consent and the study was approved by the local ethics committees of all participating institutions, and the national regulatory authorities when applicable. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. The trial was registered at clinicaltrial.gov (NCT #00424060) and at EudraCT (# 2006-001659-37).

end points and statistical analysis

The primary end point was a composite of either confirmed tumor response according to the Macdonald criteria or being alive and progression free at 6 months [9, 20], an end point we also used in other studies for recurrent disease [21, 22]. Secondary end points included overall survival, toxicity and safety, as well as population pharmacokinetics in a subgroup of patients. Adverse events were recorded according to the National Cancer Institute—Common Toxicity Criteria version 3.0.

Statistical analysis was based on a one-stage Fleming design (P0, success rate ≤8%; P1, success rate ≥23%; type I error = 10%; type II error = 10%), ≥5 successes to be observed to be considered active agent for further investigation. PFS and overall survival was calculated from date of registration until progression or death or censored at last follow-up (updated May 2010) according to the Kaplan–Meier method.

treatment and evaluations

Sagopilone (ZK-EPO, ZK 219477) was administered as a 3-h intravenous infusion every 3 weeks (one cycle). The tubing needed to be polyvinyl chloride free in order to avoid adsorption of the agent. No specific premedication (e.g. antihistamines or antiemetics) was recommended. Sagopilone was provided by Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany.

Baseline tumor imaging by MRI was to be carried out within 14 days before treatment start and after every two cycles. Treatment was to be continued until tumor progression or severe toxicity or patient refusal.

A clinical evaluation including physical and routine neurological examination was carried out before each cycle of sagopilone, with additional weekly clinic visits and complete blood count (CBC) during cycle 1 only. From cycle 2 onwards, a CBC and blood chemistry were carried out before each cycle of chemotherapy, a CBC also on day 15 (±3 days).

The starting dose of sagopilone was 16 mg/m2, and dose reductions in case of ≥ grade 3 toxicity to 12 and 9 mg/m2 were prespecified. Treatment delays for up to 2 weeks due to toxicity were allowed.

pharmacokinetic analyses

Blood for pharmacokinetic analysis was drawn on cycle 1 before treatment start, after 30 min, 5 min before the end of the 3-h infusion, 15 and 30 min after the end of the infusion and then at hours 5, 6, 27 and 168. Samples were collected into tubes containing Pefabloc® SC to prevent ex vivo degradation of sagopilone. Plasma concentrations of ZK 219477 were determined by a validated liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry method using 13C4-ZK 219477 as internal standard. The lower limit of quantification was 0.1 ng/ml.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using a commercially available software tool (EPS-Kinetica™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) without recourse to model assumptions.

results

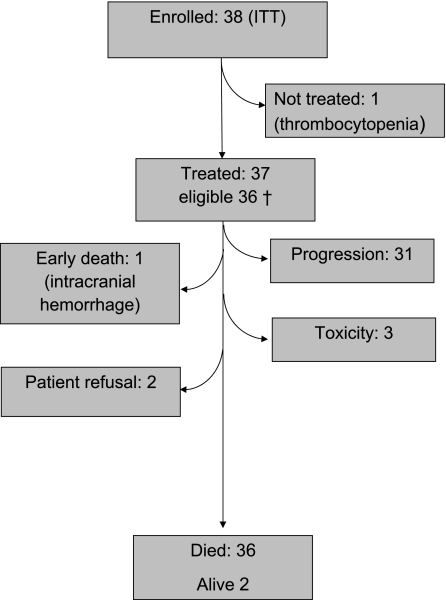

A total of 38 patients were recruited from December 2006 until August 2007; however, 1 patient with grade II thrombocytopenia at baseline never received treatment. Safety is reported on the 37 treated patients including 1 patient who did not meet the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). Tumor response was calculated on the 36 eligible patients who started therapy, and survival analyses were calculated on all 38 registered patients (intent to treat). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Median age was 57 years, and the great majority of patients had a good performance status (WHO 0 or 1). Approximately half of the patients required steroids at enrollment. A total of 100 cycles were administered to 37 patients, with a median of 2 cycles (range 1–6), 9 patients (24%) received 4 or more cycles. On average, 96% of the planned dose intensity was achieved.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Patients (N = 37a) |

| Age, median (range), years | 57 (20–76) |

| Performance status, n (%) | |

| 0 and 1 | 31 (84) |

| 2 | 6 (16) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 28 (76) |

| Female | 9 (24) |

| Prior chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| No | 1 (2) |

| TMZ/RT→TMZ | 35 (92) |

| Other | 1 (5) |

| Prior radiotherapy, n (%) | 37 (100) |

| Concomitant medication at enrollment, n (%) | |

| Steroids | 20 (54) |

| Antiepileptic drugs (non-EIAED) | 17 (46) |

Thirty-eight patients enrolled [1 patient (44 years, performance status of one, after prior TMZ/RT) not treated due to low baseline platelet count; 37 patients treated; 36 eligible].

RT, radiotherapy; TMZ, temozolomide; non-EIAED, non-enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs.

safety and toxicity

Treatment was generally well tolerated, with grade 3 fatigue and grade 3 neutropenia (inclusive 1 neutropenic infection) occurring in three patients (8%) (for details, see Table 2). Nevertheless, severe (grade 3 and grade 4) peripheral neuropathy was reported in two patients (6%), with mild signs of neuropathy recorded after cycle 2, and progression to severe grade 3 or grade 4 neuropathy after cycle 3 and 4, respectively. Grade 2 neuropathy was recorded in 3 patients, and grade 1 in 12 patients, thus almost half of the patients (46%) complained of some, albeit mostly mild, neuropathy.

Table 2.

Adverse events according to Common Toxicity Criteria

| Adverse event | Worst toxicity, No. of patients (%) |

|||

| Toxicity grade | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Hematological toxicity | ||||

| Leucopenia | 12 (32) | 4 (11) | 2 (5) | – |

| Neutropenia | 6 (16) | 1 (3) | 3a (8) | – |

| Thrombocytopenia | 5 (14) | 2 (5) | – | – |

| Anemia | 10 (27) | – | – | – |

| Neutropenic infection | 1 (3) | |||

| Non-hematological toxicity | ||||

| Fatigue | 5 (14) | 1 (3) | 3 (8) | – |

| Nausea/vomiting | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | – | – |

| Diarrhea | 2 (5) | 3 (8) | – | – |

| Neuropathy (peripheral) | 14 (32) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

response and survival

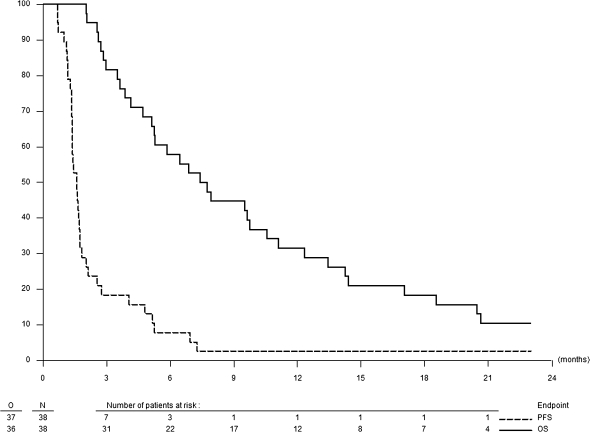

No objective responses were seen. Stable disease as the best response was reported in nine patients (25%). The PFS6 rate was 6.7% [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.3–18.7]; the median PFS was just over 6 weeks, the moment of the first reevaluation imaging (Figure 2). The median overall survival was 7.6 months (95% CI 5.3–12.3), with three patients still alive at the time of the analysis. The 1-year survival rate is 31.6% (95% CI 17.7–46.4).

Figure 2.

Overall and progression-free survival.

sagopilone discontinuation and treatment after progression

The great majority (31 patients, 81%) of patients discontinued sagopilone due to progression. Three patients discontinued due to toxicity (neuropathy, neutropenic infection and unrelated muscle infection) and two patients refused continuation in the absence of severe toxicity. One patient died during protocol therapy due to a non-treatment-related brain hemorrhage, and coagulation parameters and platelet counts were within normal limits. Treatment after progression was at the local investigators’ discretion. At the time of the analysis, 22 patients (58%) received further anticancer therapy, including 4 patients who underwent salvage surgery and 3 patients who received hyperthermia and chemotherapy combined.

pharmacokinetics

Limited pharmacokinetics was carried out on 14 patients; a sample size of 10–15 patients was estimated sufficient for the purpose of determining reliably plasma concentrations in glioma patients and allowing for cross-study validation. One subject was excluded from evaluation due to implausible plasma concentrations at the end of infusion. Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated for 11 patients as the terminal half-life/area under the concentration time curve and derived parameters could not be calculated reliably in two patients.

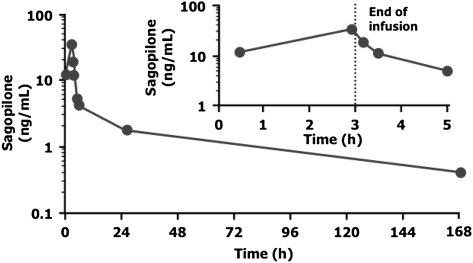

During intravenous administration of sagopilone, maximal plasma concentrations (Cmax) of 33.2 ng/ml were reached at the end of the 3-h infusion (Figure 3). Sagopilone concentrations rapidly declined to ∼30% of peak concentrations within 0.5 h after end of the infusion. After the rapid distribution phase, a long terminal disposition phase followed (mean terminal half-life of ∼53 h). The main pharmacokinetic parameters are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Serum pharmacokinetic profile of sagopilone (n = 11).

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of sagopilone in plasma after single intravenous infusion of 16 mg/m2 sagopilone over 3 h (n = 13 patients)

| Parameter | Mean valuea |

| Cmax | 33.2 ng/ml (58.4%) |

| tmax | 2.92 h (2.75–4.1) |

| AUC(0–tlast) | 234 ng·h/ml (31.3%) |

| AUC (n = 11) | 272 ng·h/ml (26.5%) |

| CL (n = 11) | 111 l/h (28.4%) |

| CLnorm (n = 11) | 58.2 l/h·m2 (24.7%) |

| Vss (n = 11) | 6774 l (36.6%) |

| MRT (n = 11) | 60.9 h (21.9%) |

| t1/2 (n = 11) | 53.0 h (21.1%) |

The geometric mean is given with the geometric coefficient of variation in parenthesis, except for tmax, for which the median and range are presented.

Cmax, maximum plasma concentration; tmax, time to reach Cmax; AUC(0–tlast), area under the concentration time curve (from 0 to the last data point above the lower limit of quantification); CL, total body clearance; CLnorm, body clearance, normalized to body surface area; Vss, apparent volume of distribution during terminal phase; MRT, mean resident time; t1/2, half-life associated with the terminal phase.

discussion

Despite encouraging preclinical data, including almost complete growth inhibition in an orthotopic glioma model, a favorable pharmacokinetic profile of a lipophylic agent with penetration across the blood–brain barrier and tolerable toxicity allowing for delivery of adequate doses [12–14, 16], we could not detect any evidence of relevant clinical antitumor activity in recurrent glioblastoma. Most patients had progressed at the time of first evaluation after only 6 weeks, contrary to a prior report on 15 heavily pretreated and thus possibly very selected patients with recurrent glioma of various histologies, who had received a median of four cycles of sagopilone and achieved disease stabilization in one third of the patients [19]. Compared with previous trials by our group with other agents that were considered ineffective against glioma, the current rate of stable disease at the first evaluation of <30% is lower than expected despite favorable patient characteristics [21–24]. Overall, sagopilone was quite well tolerated, with neurotoxicity being the most prominent side-effect despite prolongation of the infusion time. Recently reported phase I trials identified peripheral neuropathy as a dose limiting toxicity independent of schedule of administration (weekly or 3 weekly) or infusion duration (30 min versus 3 h) [17, 18]. The pharmacokinetic profile established in our study is in accordance with other trials where a 3-h infusion duration was used. As expected, peak plasma concentrations were about fivefold lower with the 3-h infusion duration compared with a 30-min infusion duration.

Despite the absence of efficacy of single-agent sagopilone against recurrent glioblastoma, the overall survival achieved in the current trial is comparable to other reports. Although this may be explained by patient selection and prognostic factors, it also suggests that that second-line salvage therapy may well have a role in the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma, despite the lack of an accepted or established regimen. A recent phase I trial investigated patupilone in conjunction with re-irradiation in 10 patients with recurrent glioma [15]. A median survival of 25.5 months (95% CI 17–33.7) and a median PFS of 13.2 months were reported, indicating that this class of agent may be particularly suited as radiation sensitizers in combination with ionizing irradiation.

Since the inception of our trial, bevacizumab has been identified as a potentially active agent for recurrent glioma. In phase II trials, median survival times of ∼9 months have repeatedly been shown, slightly longer than in our trial [10, 11, 25, 26]. Except for one, none of our patients has subsequently been treated with bevacizumab.

In conclusion, sagopilone has no relevant activity in recurrent glioblastoma. The quest for novel and better agents against malignant glioma continues.

funding

This study was supported in part by an unrestricted education grant from Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin,Germany. EORTC is supported by grants number. 2U10 CA011488-36 through 5U10 CA011488-40 from the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA, and by FOCA from Belgium.

disclosures

RS has served on paid advisory boards or received honoraria for speaking engagements from Schering-Plough, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, OncoMethylome Sciences and Merck KGaA. AT has served on paid advisory boards for MSD. PH has served on paid advisory boards for Novartis, Schering-Plough and Sigma-Tau and has received honoraria for speaking engagements from Schering-Plough and Lilly. MC received grant/research support from Novartis, Roche, Pfizer and Glaxo SmithKline. LB was an employee of Bayer Healthcare while the study was conducted. He holds no shares in the company. HW is an employee of Bayer Healthcare. MJvdB has served on paid advisory boards or received honoraria for speaking engagements from Schering-Plough, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Ark Therapeutics, Siena Biotech and Merck KGaA. AAB has received payment for consultancy and advice by Bristol-Myers Squibb, OncoMethylome Sciences, Roche, Schering-Plough. She has received honoraria from Glaxo SmithKline, Roche and Schering-Plough. JECB, JG, MF, AA, UB, WvdG, TG and DL have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We thank patients for their participation and trust and their families for the support. We would also like to acknowledge the work of the many nurses, data managers and the staff at the EORTC headquarters. We thank the collaborators at Bayer Schering, for input and critical discussions during protocol development, and Detlev Stoeckigt for the pharmacokinetic analyses. We thank Frances Godson for her invaluable editorial support. Its content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the Fonds Cancer (FOCA).

References

- 1.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Gilbert MR, Chakravarti A. Chemoradiotherapy in malignant glioma: standard of care and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4127–4136. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.8554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.BarkerII FG, II, Chang SM, Gutin PH, et al. Survival and functional status after resection of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:709–720. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199804000-00013. discussion 720–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perry JR, Belanger K, Mason WP, et al. Phase II trial of continuous dose-intense temozolomide in recurrent malignant glioma: RESCUE Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2051–2057. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wick W, Puduvalli VK, Chamberlain MC, et al. Phase III study of enzastaurin compared with lomustine in the treatment of recurrent intracranial glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1168–1174. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Franceschi E, et al. Fotemustine as second-line treatment for recurrent or progressive glioblastoma after concomitant and/or adjuvant temozolomide: a phase II trial of Gruppo Italiano Cooperativo di Neuro-Oncologia (GICNO) Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64:769–775. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-0926-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frenay M, Giroux B, Khoury S, et al. Phase II study of fotemustine in recurrent supratentorial malignant gliomas. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27:852–856. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yung WK, Mechtler L, Gleason MJ. Intravenous carboplatin for recurrent malignant glioma: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:860–864. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.5.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong ET, Hess KR, Gleason MJ, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors in recurrent glioma patients enrolled onto phase II clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2572. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4733–4740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wick W, Weller M, van den Bent M, Stupp R. Bevacizumab and recurrent malignant gliomas: a European perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e188–e189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann J, Vitale I, Buchmann B, et al. Improved cellular pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics underlie the wide anticancer activity of sagopilone. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5301–5308. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klar U, Buchmann B, Schwede W, et al. Total synthesis and antitumor activity of ZK-EPO: the first fully synthetic epothilone in clinical development. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:7942–7948. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoffmann J, Fichtner I, Lemm M, et al. Sagopilone crosses the blood-brain barrier in vivo to inhibit brain tumor growth and metastases. J Neurooncol. 2009;11:158–166. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-072). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fogh S, Machtay M, Werner-Wasik M, et al. Phase I trial using patupilone (epothilone B) and concurrent radiotherapy for central nervous system malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:1009–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fichtner I, Rolff J, Soong R, et al. Establishment of patient-derived non-small cell lung cancer xenografts as models for the identification of predictive biomarkers. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6456–6468. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmid P, Kiewe P, Possinger K, et al. Phase I study of the novel, fully synthetic epothilone sagopilone (ZK-EPO) in patients with solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:633–639. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold D, Voigt W, Kiewe P, et al. Weekly administration of sagopilone (ZK-EPO), a fully synthetic epothilone, in patients with refractory solid tumours: results of a phase I trial. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1241–1247. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silvani A, Gaviani P, Fiumani A, et al. Systemic sagopilone (ZK-EPO) treatment of patients with recurrent malignant gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2009;95:61–64. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9890-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macdonald DR, Cascino TL, Schold SC, Jr, Cairncross JG. Response criteria for phase II studies of supratentorial malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1277–1280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raymond E, Brandes AA, Dittrich C, et al. Phase II study of imatinib in patients with recurrent gliomas of various histologies: a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4659–4665. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Bent M, Brandes A, Rampling R, et al. Randomized phase II trial of erlotinib versus temozolomide or carmustine in recurrent glioblastoma. Report from EORTC Brain Tumor Group study 26034. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1268–1274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Den Bent MJ, Grisold W, Frappaz D, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) open label phase II study on glufosfamide administered as a 60-minute infusion every 3 weeks in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1732–1734. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raymond E, Campone M, Stupp R, et al. Multicenter phase II pharmacokinetic study of RFS-2000 (9-nitro-camptothecin) administered orally 5 days a week in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:1348–1350. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreisl TN, Kim L, Moore K, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent bevacizumab followed by bevacizumab plus irinotecan at tumor progression in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:740–745. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins A, Herndon JE, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4722–4729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]