1. Introduction

Synthetic dyes are used as colorants in the textile, food, plastic and biomedical industries. Globally, about 50,000 tons of textile dyes are discharged to the environment annually [1]. They are the most visible sign of water pollution as some dyes are visible at concentrations as low as 0.005 mg/l [2]. Since some are potential health hazards because they and/or their degradation products are toxic [3], environmental regulatory agencies in several countries have adopted stringent regulations for the discharge of coloured effluents from textile and dyestuff manufacturers. No single conventional technology can remove all classes of dyes [4–5]. They adsorb to activated sludge and are poorly degraded in traditional wastewater treatment. Lignin-degrading enzymes (such as lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, and laccase (phenol oxidase)) of white rot fungi have been shown to degrade a wide range of persistant organic pollutants including textile dyes [6–8].

Laccase has attracted significant interest in the decolorization of textile wastewaters (reviewed in [4]). It is a copper oxidase that efficiently degrades anthraquinone dyes and dyes with phenolic moieties [7–9]. Unlike lignin or manganese peroxidase, laccase requires only molecular oxygen as a co-substrate and may be more suitable biocatalysts for industrial and bioremediation applications. Laccase can degrade phenolic compounds in wine distillery wastewater [10], estrogens in municipal wastewater [11] and textile dyes in textile wastewaters [6]. In the latter investigation, immobilized Coriolopsis gallica laccase decolorized 10 batches of an industrial waste effluent containing Direct Blue 200, Direct Red 80 and Direct Black 22. The removal efficiency decreased as the number of decolorization batches increased and the authors could not identify the cause of enzyme inactivation. Although a few studies have used laccase to decolorize industrial textile waste effluents, there is no kinetic investigation of the effects of effluent components on enzyme activity.

Textile wastewaters contain not only residual dyes, but also auxiliary chemicals such as surfactants, salts, oils and greases. Surfactants are amphiphilic molecules with a polar head and hydrophobic carbon chains. Although a growing number of studies focus on laccase activity in reverse micelles [12–14], few investigations have analyzed the effect of surfactants on enzymatic dye decolorization. Harazono and Nakamura [15] showed that MnP from Phanerochaete sordida required Tween 80, a non-ionic surfactant, to decolorize a mixture of reactive dyes (Reactive black 5, Reactive red 120, Reactive green 5 and Reactive orange 14) but was inhibited by another surfactant, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). The authors thought that inhibition occurred because PVA interrupted the lipid peroxidation which generates reactive radicals. Abadulla et al. [16] reported that Univadine PA (anionic surfactant), Tinegal MR (cationic surfactant) and Albegal FFA (wetting agent) inhibited 2,6-dimethoxyphenol oxidation by Trametes hirsuta laccase by 17.9, 5.2 and 2.3% respectively but the effects on dye decolorization were not examined. Moreover, there are no studies which have examined the effect of surfactants on decolorization kinetics by laccase.

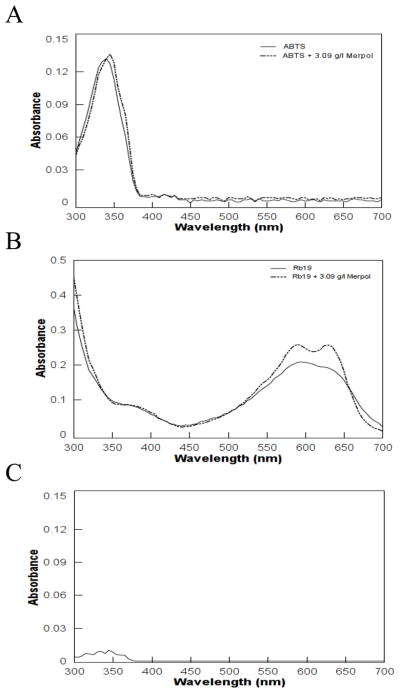

Merpol is a non-ionic, polyethylene oxide surfactant used as a wetting and emulsifying agent to achieve better fabric permeation to allow an even dyeing of textile fabrics. There is no report on the effects of a non-ionic surfactant like Merpol on dye decolorization or decolorization kinetics. Since such a surfactant could be in the dye effluent, it is useful to know whether it affects enzymatic decolorization. This investigation therefore analyzes the impact of Merpol on the decolorization of an anthraquinone dye, Reactive blue 19 (Figure 1A), by laccase from Trametes versicolor and compares the decolorization kinetics with laccase oxidation of 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Structure of (A) Reactive blue 19 and (B) ABTS

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals

2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS), Reactive blue 19, Merpol HCS, Q-sepharose, sodium dihydrogenophosphate, sodium acetate and Trametes versicolor laccase were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Canada (Oakville ON, Canada).

2.2 Enzyme preparation

Four hundred milligrams of lyophilized Trametes versicolor laccase was dissolved in 60 ml of 20 mM NaH2PO4 at pH 7, centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 2 hours, and then filtered with a Whatman paper and Millipore filters (0.45 μM). The filtrate was dialyzed against 20 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7 for 20 hours at a dilution factor of approximately 5,000 then passed through a Q-Sepharose anion exchange column pre-equilibrated with 20 mM NaH2PO4 at pH 7. Laccase was eluted in one step using 150 mM NaCl. The eluate was dialyzed against 50 mM NaOAc/50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 5.

2.3 Enzyme assay and quantification

Laccase activity was determined by monitoring with a spectrophotometer the generation of 2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radicals (ABTS•−) at 420 nm from the oxidation of ABTS [17] at 23 ± 1°C using a Spectramax 250 plate reader with the SOFTmax PRO software package (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale CA, USA). The assay mixture contained 0.5 mM ABTS, 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) and the enzyme aliquot for a total reaction mixture of 180 μl. The path length of absorbance in the well for this volume was 0.5 cm. One unit of laccase activity (U) was defined as the amount of enzyme that formed 1 μmol ABTS•− per minute. Protein concentration was measured by the absorbance at 280 nm and corrected for scattering effects with absorbance readings at 320 nm.

2.4 Dye concentration and spectroscopic analysis

The concentration of Reactive blue 19 was measured with a Unicam UV1 spectrophotometer (Spectronic Unicam, Cambridge, UK) or Spectramax 250 plate reader at the dye’s maximum absorption wavelength (592 nm). The absorbance coefficient was determined to be 10,044 M−1cm−1 (in 50 mM NaOAc/50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 5) with a calibration curve from 0 to 45.3 μM. Spectral scans of the dye or ABTS with (3.09 g/l) or without Merpol were conducted.

2.5 Saturation equilibrium binding

Equilibrium binding assays were done by incubating dye concentrations of 16, 32, 48, 64, 80, 96, 112 or 128 μM at a fixed Merpol concentration of 0.386, 0.773 or 1.03 g/l. The assay mixture was buffered with 50 mM NaOAc/50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 5. Assays were conducted in 96-well plates that were pre-saturated with the surfactant for 4 hours. The dye-Merpol binding was allowed to achieve equilibrium for 45 minutes, after which the absorbance readings did not fluctuate with time. The dye-Merpol complex was monitored with the Spectramax 250 at 630 nm.

2.6 Effect of Merpol on Reactive blue 19 decolorization and on ABTS oxidation and kinetic studies

Initial dye decolorization rates were measured in the presence of 0, 0.773, 1.55, 2.58 or 3.09 g/l Merpol. The decolorization mixture included 120 nM laccase and 100 μM Reactive blue 19. The rate of ABTS oxidation was measured in the presence of 0, 1.55 or 3.09 g/l Merpol. The assay mixture also contained 0.274 nM laccase and 500 μM ABTS. All assays were conducted at pH 5 in 50 mM NaOAc/50 mM NaH2PO4. For the kinetic studies, initial rates were similarly determined for 0 to 400 μM Reactive blue 19 and for 0 to 1000 μM ABTS. The enzyme concentration for each reaction was adjusted until a detectable linear portion of the progress curve could be measured for at least eight minutes (30 minutes assay time). All experiments were done in triplicate and the results shown are averages with the error bars representing the standard error.

2.7 Estimation of kinetic constants

The estimation of kinetic parameters and the inhibition constants were determined by nonlinear least square regression (sums of the squares were minimized with the Gauss-Newton algorithm with equal weighting for each parameters) using the R statistical package (R project for statistical computing, CRAN) and Systat (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Although in the data analysis each data point was fitted to the model, the triplicates were averaged and the model fitted through the average values for graphical presentation.

3. Results

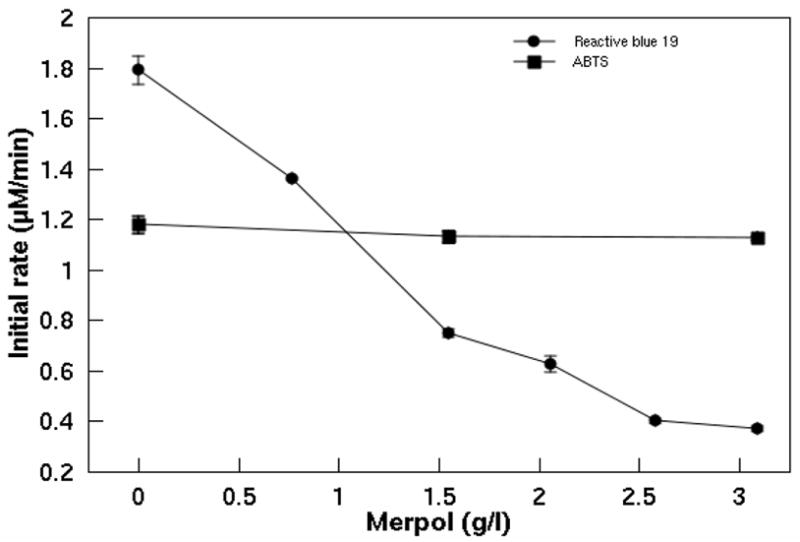

3.1 Effect of Merpol on the rate of ABTS oxidation and dye decolorization by laccase

Increasing the Merpol concentration from 0 to 3.09 g/l had little effect on ABTS oxidation while the rate of Reactive blue 19 decolorization decreased significantly from 1.79 to 0.37 μM/min (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of Merpol on the rate of ABTS oxidation and Reactive blue 19 decolorization by laccase. Concentrations of 0.274 and 120 nM laccase were used for ABTS oxidation and Reactive blue 19 decolorization respectively. The assay mixtures were buffered in 50 mM NaOAc/50 mM NaH2PO4 at pH 5 and a temperature of 22 ± 1° C. Each data point is the average of triplicates and error bars represent the standard deviation.

3.2 Effect of Merpol on the kinetics of ABTS oxidation and Reactive blue 19 decolorization

The Michaelis-Menten rate equation (equation 1) for an enzyme-catalyzed reaction

describes the dependence of the reaction rate (v) on the molar concentration of the free substrate [S] and the total enzyme [E]tot [18–19]. The kcat is the turnover number and is usually expressed the unit of s−1 and KM is the affinity constant as well as the molar concentration of the free substrate that yields a reaction rate equal to half the maximum rate, vmax = kcat [E]tot.

| (1) |

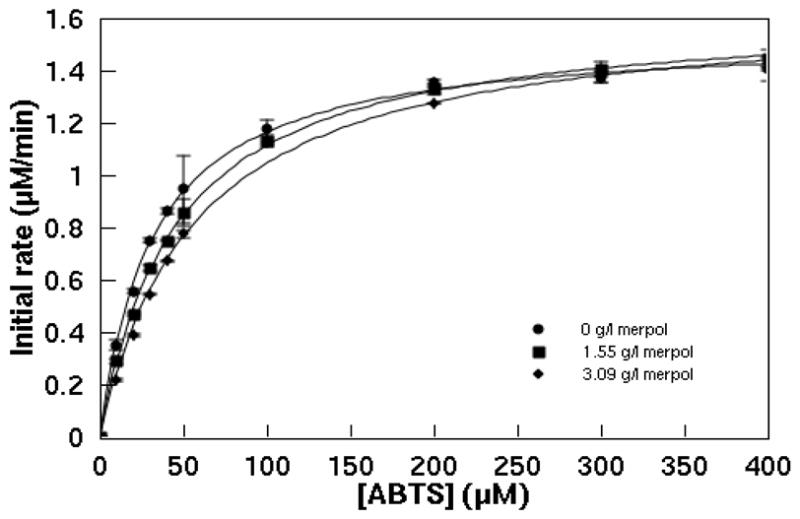

ABTS oxidation by laccase followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics at all Merpol concentrations tested (0 to 3.09 g/l) (Figure 3). Although Figure 3 shows little effect on ABTS oxidation, the kcat increased slightly from 93.6 to 98.3 s−1 and the KM from 32.1 to 54.9 μM (Table 1) indicating that the surfactant reduced the affinity of the enzyme for ABTS while slightly enhancing the enzyme activity.

Figure 3.

Effect of Merpol on ABTS oxidation by 0.274 nM laccase in 50 mM NaOAc/50 mM NaH2PO4 at pH 5 (T = 22 ± 1°C). Comparison of experimental data (each symbol is the average of triplicates and the error bars represent the standard deviation) and the Michaelis-Menten model (equation 1, solid lines).

Table 1.

Effect of Merpol on ABTS oxidation and the decolorization of Reactive blue 19 by 120 nM laccase in 50 mM NaOAc/50 mM NaH2PO4, pH 5. The kinetic parameters for ABTS were determined using the Michaelis-Menten model (equation 1) and for Reactive blue 19 using the derived inhibition model (equation 13).

| Steady-state kinetics

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Merpol (g/l) | kcat (s−1) | KM (μM) | kcat/KM (× 105 M−1 s−1) | n (μmol/g) | Kd (μM) |

| ABTS | |||||

| 0 | 93.6 ± 0.7 | 32.1 ± 1.2 | 29.2 | - | - |

| 1.55 | 95.2 ± 0.7 | 42.0 ± 1.4 | 22.7 | - | - |

| 3.09 | 98.3 ± 1.0 | 54.9 ± 2.7 | 18.0 | - | - |

| Reactive blue 19 | |||||

| 0 – 3.09 | 1.65 ± 0.07 | 537 ± 36 | 80.5 ± 2.2 | 38.3 ± 3.4 | |

|

| |||||

| Saturation equilibrium Reactive blue 19-Merpol binding

| |||||

| Merpol (g/l) | γ630 (l g −1 cm−1) | Kd (μM) | |||

|

| |||||

| 0 – 1.03 | 0.119 ± 0.010 | 44.1 ± 10.1 | |||

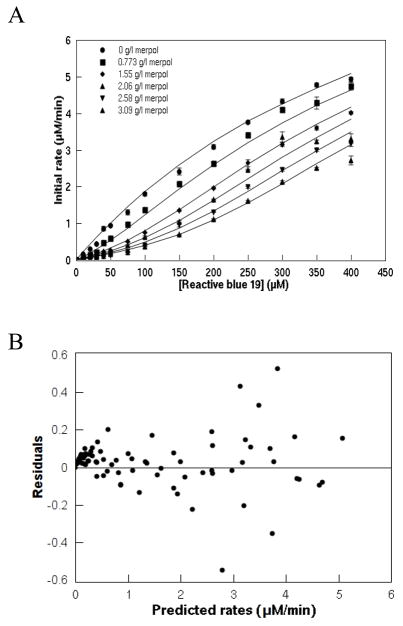

3.3 Spectroscopic analysis of Reactive blue 19 with Merpol

Spectroscopic analysis of Reactive blue 19 without Merpol or laccase showed a maximum absorbance at 592 nm. With the addition of 3.09 g/l Merpol, a second peak appeared at 630 nm. There was a slight but insignificant shift in the spectral behavior of ABTS after Merpol addition (Figures 4A and B) and Merpol alone did not absorb in the visible range (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Spectrophotometric analysis of (A) ABTS, (B) Reactive blue 19, with and without Merpol and (C) 3.09 g/l Merpol alone. The mixture contained 50 μM Reactive blue 19 or 0.5 μM ABTS and 3.09 g/l Merpol in 50 mM NaOAc/50 mM NaH2PO4 buffer at pH 5 (T = 22 ± 1°C).

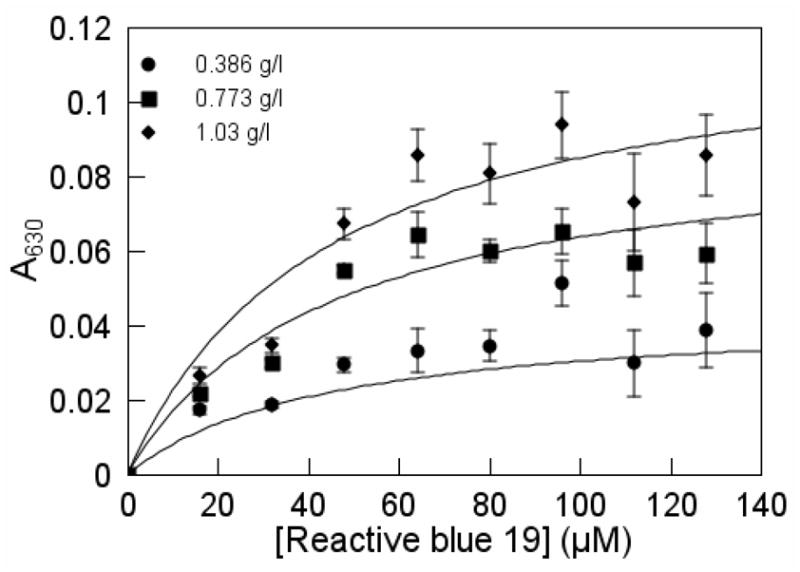

3.4 Saturation equilibrium binding

The dye-Merpol complex was monitored spectrophotometrically at 630 nm in Figure 5 and was calculated by subtracting the absorbance of the dye at that wavelength from the absorbance of the dye-surfactant mixture. As shown in Figure 5, the dye-Merpol complex increased with increasing dye concentration and tended to plateau at high concentrations. The derivation of the model fitted through the points is presented in the next section.

Figure 5.

Saturation equilibrium of Reactive blue 19 and Merpol binding. The assay mixture was buffered with 50 mM NaOAc/50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 5 (T = 22 ± 1°C).

3.5 Estimation of Kd from the saturation equilibrium experiment

The interaction of Merpol (M) and the anthraquinone dye (S, Reactive blue 19) to form a complex (SM) was assumed to achieve equilibrium rapidly and can reach saturation. The strength of binding was characterized by the dissociation constant, Kd from a saturation equilibrium relationship

| (2) |

where [SM] is the concentration of the complex, [M]total is the total concentration of Merpol in g/l and [S] is the dye concentration in molar units. Since the molecular weight of the surfactant is proprietary and its molecular weight was not available at the time of study, neither the concentration of the SM complex nor its absorption coefficient, ε630, could be determined on a molar basis. Thus, the relationship of the absorbance at 630 nm as a function of the dye concentration was modified to yield

| (3) |

where γ is a lumped absorption coefficient equal to 2ε630 with units of l g−1 cm−1. With equation 3, Kd was estimated to be 44.1 ± 10.1 μM and γ to be 0.119 ± 0.010 l g−1 cm−1 (Table 1).

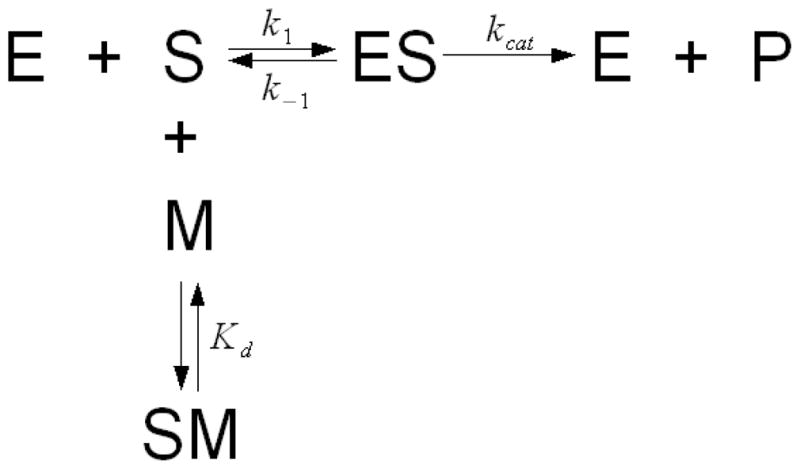

3.6 Kinetic modeling of the effect of Merpol on decolorization of Reactive blue 19 by laccase

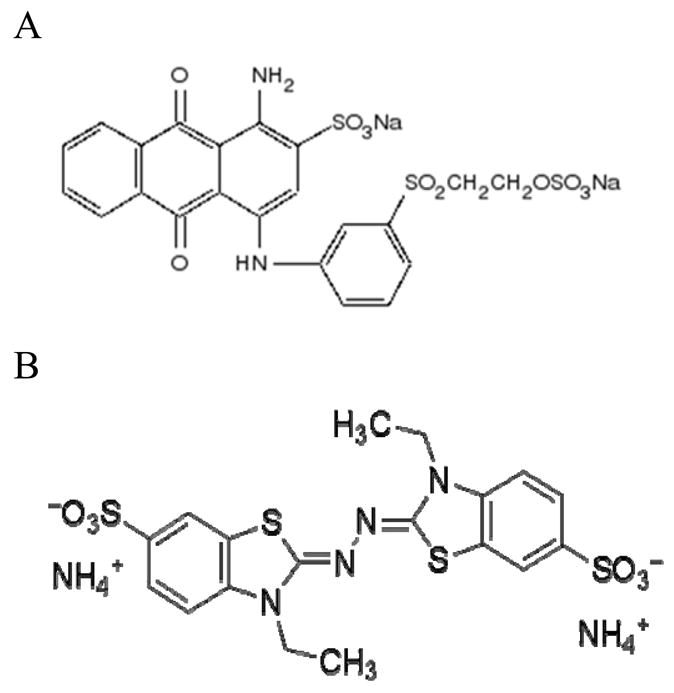

Without Merpol, Reactive blue 19 decolorization also followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Figure 6) but as the Merpol concentration increased, the initial rates decreased and decolorization kinetics became increasingly sigmoïdal. In the presence of Merpol, the dependence of initial rates on the initial dye concentrations did not follow Michaelis-Menten kinetics. Hence, a modified rate equation is hypothesized where the inhibitor (M, i.e. Merpol) binds to the free substrate (S, i.e. Reactive blue 19) but not the enzyme (E, laccase) (Figure 7). Furthermore, the enzyme can convert the free dye only to decolorized products (P) as the dye bound by Merpol is unavailable for decolorization. Since the total dye concentration added to the reaction mixture, [S]T, is the sum of the free dye [S], the enzyme-dye complex [ES] and the dye-Merpol complex [SM] concentrations, [S] can be expressed as

Figure 6.

Inhibition of laccase decolorization of Reactive blue 19 by Merpol (A) and the residual plot (B). The laccase concentration was 120 nM in 50 mM NaOAc/50 mM NaH2PO4 buffered at pH 5. Comparison of experimental data (each symbol is the average of triplicates and the error bars represent the standard deviation) and the substrate depletion model (equation 5, solid lines).

Figure 7.

Kinetic scheme for the inhibition of dye decolorization by substrate depletion.

| (4) |

Given that [S] ⋙ [E], then [S] ⋙ [ES] so that [ES] can be omitted and equation 4 simplified to

| (5) |

where [M]T is the total Merpol concentration. Substituting equation 5 in equation 1, we obtain

| (6) |

The free Merpol concentration, [M], can be estimated as

| (7) |

and the dissociation constant, Kd, for M binding to S is

| (8) |

Solving equation 8 for [SM],

| (9) |

The number of inhibitor (Merpol) binding sites, n (μmol per g of Merpol), is proportional to the total inhibitor concentration [M]T such that

| (10) |

where n is the μmoles of dye bound to 1 gram of Merpol and [M]o is the total surfactant concentration added (in g/l). The correlation between the decolorization rate, the dye and surfactant concentrations was reasonably described by the modified rate equation (Equation 6) (solid lines) which also predicted the sigmoidal kinetic behavior (Figure 6). Kinetic parameters were determined (Table 1) and the number of μmoles of dye bound to 1 gram of Merpol, n, was found to be 80.3 μmol/g.

4. Discussion

The results in this study show that Merpol had little effect on laccase but affected the decolorization of Reactive blue 19. Since Merpol slightly increased the ABTS oxidation rate (~ 5.0%) (Table 1), the surfactant may have a small stabilizing and/or inducing effect on laccase but did not seem to interact with the enzyme significantly. Basto et al. [20] also showed improved laccase stability in the presence of polyvinyl alcohol in the ultrasonic decolorization of Indigo carmine. However in the present study, when Reactive blue 19 was the substrate, Merpol clearly inhibited its decolorization. Although Abadulla et al. [16] did not examine the effect of surfactants on enzymatic dye decolorization, they found that Univadine PA (anionic surfactant), Tinegal MR (cationic surfactant) and Albegal FFA (wetting agent) inhibited the oxidation of 2,6-dimethoxyphenol by laccase. The inhibition was less severe than that obtained with Reactive blue 19. Their highest inhibition of 17.9% was obtained with 2 g/L Univadine PA while with 2 g/L Merpol, Reactive blue 19 decolorization was inhibited by approximately 50%.

Since Merpol had little effect on the enzymatic oxidation of ABTS but significantly inhibited the enzymatic decolorization of Reactive blue 19, the surfactant must have interacted with the dye. This interaction was detected in the absorbance spectral scan by the appearance of a second peak of at 630 nm (Figure 4B) that could correspond to the absorption of the dye-Merpol complex. This wavelength shift was not observed for ABTS. It is also clear that Merpol is not responsible for the second peak since it did not absorb in the visible range.

A model of inhibition by substrate depletion where the dye molecules bind to Merpol molecules to reduce the amount of free dye available to react with laccase describes the decolorization kinetics. This model is in good agreement with the experimental data as seen in Figure 6A and the residual plot also shows no bias (Figure 6B). In addition, the kinetic mechanism is supported by saturation equilibrium binding and spectroscopic data that clearly show that Merpol binds Reactive blue 19. The difference between the Kd estimated from the equilibrium binding experiment and from the kinetic model are not statistically significant (α = 0.05).

The dye may have interacted with the surfactant molecules or with the micelles as all Merpol concentrations were above the critical micelle concentration of 0.5 g/l. It is not clear why the surfactant interacted with the dye but not with ABTS. Although Reactive blue 19 most likely bears a net negative charge at pH 5, hydrophobic interactions with Merpol may be dominant. This may partially explain our results and is supported by Tokuda et al. [21] who has shown that both electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions affected decolorization rates by peroxide bleaching agents in the presence of surfactant molecules.

The proposed inhibition model may also explain the results of Hu et al. [22] where Tween 80 significantly inhibited the oxidation of benzo[k]fluoranthene (BaP) by laccase immobilized on kaolinite. Tween 80 was used to increase the solubility of BaP in order to increase its availability to the enzyme. However, as the apparent solubility increased, BaP molecules were probably entrapped inside the micelles which then presented a barrier between BaP and the immobilized laccase and resulted in an apparent inhibition.

This is the first study to show that enzymatic decolorization can be affected by the interaction between a dye and a surfactant. This is significant since surfactants are common in dye effluents and can affect not only biological decolorization (whether enzymatic or with a fungal culture) but also physical or chemical decolorization processes [21]. The efficiency of the process will most likely diminish with the degree of interaction between the dye and the surfactant and the quantity of the surfactant. This impact would be even greater at low dye concentrations which are typical of most dye effluents. Thus, it is important to better understand the nature of these interactions, not only to predict decolorization but also to determine how these interactions can be minimized and would be useful in developing a commercial process.

5. Conclusions

We have examined the effect of a non-ionic surfactant, Merpol, on the enzymatic oxidation of ABTS and decolorization of Reactive blue 19 using laccase. The surfactant had no significant effects on the enzyme itself as it had no effect on ABTS oxidation. However, Reactive blue 19 decolorization was inhibited with increasing surfactant concentration. Spectral scans of the dye with and without Merpol and analysis of kinetic data showed that decolorization rates depended on the interaction between the dye and the surfactant. The inhibition model fitted the data suitably since the dye concentration decreased as the dye is removed from the reaction as it binds to the surfactant molecule and/or is sequestered into micelles. This is the first study to show this effect in enzymatic dye decolorization.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by a Premier’s Research Excellence Award, Government of Ontario; and the Chancellor’s Award of Queen’s University as well as a Queen’s Graduate Award to P.-P. Champagne.

References

- 1.Lewis DM. Coloration in the next century. Rev Prog Coloration. 1999;29:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Neill C, Hawkes F, Hawkes D, Lourenco N, Pinheiro H, Delee W. Colour in textile effluents-sources, measurement, discharge consents and simulation: a review. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 1999;74:1009–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moawad H, Abd El-Rahim WM, Khalafallah M. Evaluation of biotoxicity of textile dyes using two bioassays. J Basic Microbiol. 2003;43:218–229. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200390025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husain Q. Potential applications of the oxidoreductive enzymes in the decolorization and detoxification of textile and other synthetic dyes from polluted water: A review. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2006;26:201–221. doi: 10.1080/07388550600969936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson T, McMullan G, Marchant R, Nigam P. Remediation of dyes on textile effluent: a critical review on current treatment technologies with proposed alternative. Biores Technol. 2001;77:247–255. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(00)00080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reyes P, Pickard MA, Vasquez-Duhalt R. Hydroxybenzotriazole increases the range of textile dyes decolourizaed by immobilized laccase. Biotechnol Lett. 1999;21:875–880. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nyanhongo G, Gomes, Mester T, Gubitz G, Zvauya R, Read J, Steiner W. Decolourization of textile dyes by laccase from a newly isolated strain of Trametes modesta. Water Res. 2002;36:1449–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(01)00365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Champagne PP, Ramsay JA. Contribution of manganese peroxidase and laccase to dye decoloration by Trametes versicolor. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;69:276–285. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-1964-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu J, Yu J. Laccase catalyzed decolourization of synthetic dyes. Water Res. 1999;33:3512–3520. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strong PJ, Burgess JE. Fungal and enzymatic remediation of a wine less and five wine-related distillery wastewaters. Biores Technol. 2008;99:6134–6142. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auriol M, Filali-Meknassi Y, Rajeshwar DT, Adams CD. Laccase-catalyzed conversion of natural and synthetic hormones from a municipal wastewater. Water Res. 2007;41:3281–3288. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khmelnitsky Y, Gladilin AK, Roubailo VL, Martinek K, Levashov AV. Reversed micelles of polymeric surfactants in nonpolar organic solvents. A new microheterogeneous medium for enzymatic reactions. Eur J Biochem. 1992;206:737–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michizoe J, Ichinose H, Kamiya N, Maruyama T, Masahiro G. Biodegradation of phenolic environmental pollutants by a surfactant-laccase complex in organic media. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;99:642–647. doi: 10.1263/jbb.99.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu ZH, Shao M, Cai RX, Shen P. Online studies on intermediates of laccase-catalyzed reaction in reversed micelles. J Colloid Interf Sci. 2006;294:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2005.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harazono K, Nakamura J. Decolorization of mixtures of different reactive textile dyes by the white rot basidiomycete Phanerochaete sordida and inhibitory effect of polyvinyl alcohol. Chemosphere. 2005;59:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.09.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abadulla E, Tzanov T, Costa S, Robra KH, Cavaco-Paulo A, Gubitz GM. Decolourization and detoxification of textile dyes with a laccase from Trametes hirsute. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3357–62. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.8.3357-3362.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfenden B, Wilson R. Radical-cations as reference chromogens in kinetic studies of one-electron transfer reactions. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1982;II:805–812. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segel IH. Enzyme kinetics: Behaviour and analysis of rapid equilibrium and steady-state enzyme systems. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1993. p. 957. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leskovac V. Comprehensive enzyme kinetics. 1. Kluwer Academic Publishers; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basto C, Silva CJ, Gubitz, Cavaco-Paulo A. Stability and decolourization ability of Trametes villosa laccase in liquid ultrasonic fields. Ultrason Sonochem. 2007;14:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tokuda J, Ohura R, Iwasaki T, Takeuchi Y, Kashiwada, Nango M. Decolorization of azo dyes by hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by water-soluble manganese porphyrins. Text Res J. 1999;69:956–960. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu X, Zhao X, Hwang HM. Comparative study of immobilized Trametes versicolor laccase on nanoparticles and kaolinite. Chemosphere. 2007;66:1618–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]