Abstract

Objectives

To determine if negative cognitions accounted for the associations of sexual victimization with depression and alcohol-related problems among first-year college women.

Methods

Data were collected from 719 first-year college females. Structural equation modeling was used to test if negative cognitive schemas mediated the links between sexual victimization and 2 outcomes.

Results

Sexual victimization was related to higher levels of depression and alcohol-related problems, and negative cognitions partially accounted for these associations. Whether or not the incident happened in a dating context did not impact on cognitions.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that preventing negative cognitions might help offset adverse consequences associated with sexual victimization.

Keywords: sexual victimization, cognitions, coping, college females

Sexual victimization is a significant problem among college students. Rates of sexual victimization are 3 times higher for females in college compared to females of similar ages in the general population.1 In a national survey of college students, 7% reported a completed rape, 10% reported an attempted rape, 11% reported sexual coercion, and 28% reported unwanted sexual contact during the previous year.2 Data from a more recent national survey of college women suggest that approximately 20% experience sexual victimization at some time during their college years.3 Prospective data on sexual victimization among college women are limited. However, one study that surveyed women at the end of each of their 4 years in college found that 31% had experienced some form of sexual victimization during their first year and that rates declined slightly as women progressed through their college years: 27% at the end of their second year, 26% at the end of their year, and 24% at the end of their fourth year.4 These data suggest that it is during the first year of college that women are at the highest risk for sexual victimization.

Women who experience sexual victimization suffer numerous negative psychological and behavioral outcomes.5,6 Victims of sexual violence are at increased risk for depressive symptoms, as found in many studies,7–10 including studies with college students. For example, data collected from college students who participated in the International Dating Violence Study indicated that sexual victimization was significantly associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. This finding held even after controlling for physical and psychological victimization.11 Victims also are more likely than their nonvictim counterparts to evidence alcohol problems.6,12,13 This finding, too, has been supported with college students. For example, college women who had experienced unwanted sexual contact reported having higher levels of alcohol-related negative consequences, consuming more alcoholic drinks per day, and drinking more days each week than did their nonvictimized counterparts.14

Research suggests that those most vulnerable to negative outcomes are those who perceive the traumatic event as having broad implications about the nature of the world and their ability to cope with it.15 Cognitions that include negative assumptions or schemas about one’s self, the world, and other people contribute to poorer psychological adjustment.16,17

Research on the role of cognitive schemas dates back to Piaget’s (1952) work on assimilation and accommodation.18,19 Schema change can be slow or abrupt.19 In the case of changes following trauma, they are more likely to be sudden. Cognitive models of PTSD propose that PTSD results when the experience of the traumatic event will not fit into one’s prior understanding of things.19 Differences in reactions to trauma can be attributed to differences in the "nature and content of schematic representations (p.233)."19 This point is supported by research that highlights the role of posttraumatic cognitions in predicting the psychological consequences of victimization.15,17,20,21

The current study examined the role of negative cognitions in the link between sexual victimization and 2 outcomes, depression and alcohol-related problems. The study adds to the literature by examining this question in a sample of first-year college females and by testing if a cognitive mediating model applied for sexual victimization perpetrated in both nondating and dating situations.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Study participants included 719 respondents who were recruited from the population of females enrolled as full-time students at a southeastern university. Data were collected over the course of 6 weeks at the end of the respondents’ first year as college students. Slightly over half (54%) of eligible women (n=1339) participated in the study. The sample did not differ from the population of first-year females on race or sorority status. However, the sample had a significantly higher grade point average at the end of their fall semester than did the population as a whole. Almost all (99%) of the women were aged 18 and 19 years. Four women were 20 years old. The majority of the women (85%) were white, with the remaining being black (11%) and other (4%).

Women were recruited into the study in 3 different ways: (1) sending an e-mail message to all first-year females inviting them to the student health center to complete an anonymous survey on women’s health; (2) posting flyers around campus inviting participation in the study at the health center; and (3) setting up a data collection site outside of the library and the campus bookstore. The study was approved by the university’s institutional review board. Participants provided written informed consent prior to completing the survey. Students were informed that the survey was anonymous, that it should take approximately 30 minutes to complete, and that they would receive a $15.00 gift card for their time. They deposited completed surveys in a locked box, were given their incentive, signed their names verifying receipt of payment, and were provided a referral sheet for counseling options.

Measures

Sexual victimization

The Sexual Experiences Survey (SES) was used to assess for sexual victimization experienced since school began in August 2006.2 The SES uses behaviorally specific questions to assess for completed rape, attempted rape, sexual coercion, and unwanted sexual contact. The SES is one of the most widely used measures of sexual victimization,4,22–24 and has demonstrated reliability and validity when used with college students.2 Based on their responses, women were classified according to the most severe type of sexual victimization they had experienced. For the current study, both a continuous measure (4 = completed rape, 3 = attempted rape, 2 = coercion, 1 = unwanted sexual contact, 0 = nonvictim) and a dichotomous measure (1 = victim of any type of sexual victimization, 0 = nonvictim) were used.

Dating violence

Using the dichotomous scoring of sexual victimization, we created a 3-level variable: nonvictimization, nondating sexual victimization, and dating sexual victimization. Nondating victimization included incidents perpetrated by strangers, nonromantic acquaintances, and relatives; dating victimization included incidents perpetrated by romantic acquaintances, casual dates, or first dates. Contrast-coding was used, with one contrast variable comparing nonvictims to victims of any type of sexual victimization (−1, .5, .5) and the other contrast variable comparing victims of nondating victimization to victims of dating sexual violence (0, −1, 1).

Negative cognitions

The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI) is a 36-item instrument with 3 subscales that assess for negative cognitions about the self, negative cognitions about the world, and self-blame.15 Responses are made on a 7-point Likert scale. The PTCI has demonstrated internal consistency and test-retest reliability, as well as convergent and discriminant validity. In the current sample, the α’s ranged from .82 to .94.

Depression

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depressed Mood Scale (CES-D), a 20-item self-report measure, was used to assess for depressive symptoms over the past week using a 4-point scale.25 The CES-D has demonstrated internal consistency reliability, test-retest reliability, construct validity, and discriminant validity. In the current sample, the scale’s α was .81.

Alcohol-related negative consequences

The 23-item Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI) was used to assess negative consequences due to drinking. Items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale, and responses were summed across items. The scale has demonstrated convergent and discriminant validity, as well as internal consistency reliability.26 In the current sample, the scale’s α was .90.

Statistical Analyses

Mplus (version 4) was used to conduct 2 structural equation models (SEM).27 The first SEM used the continuous sexual victimization measure as the predictor, and the second SEM used the 2 contrast-coded variables as predictors. Maximum likelihood methods were used to examine the overall fit of the model. Criteria used to evaluate model fit included χ2/df ratio, with ratios less than 3 indicative of good fit, the comparative fit index (CFI) with values greater than .95 indicative of good fit, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), with values less than .06 indicative of better fit.28–30

RESULTS

Among the women surveyed, 18% had experienced some form of sexual victimization (8% unwanted sexual contact, 4% sexual coercion, 3% attempted rape, and 3% completed rape) during the approximate 8 months that had elapsed since the school year started. Among victims, 58% experienced the incident with a dating partner and 42% experienced the incident with a nondating partner.

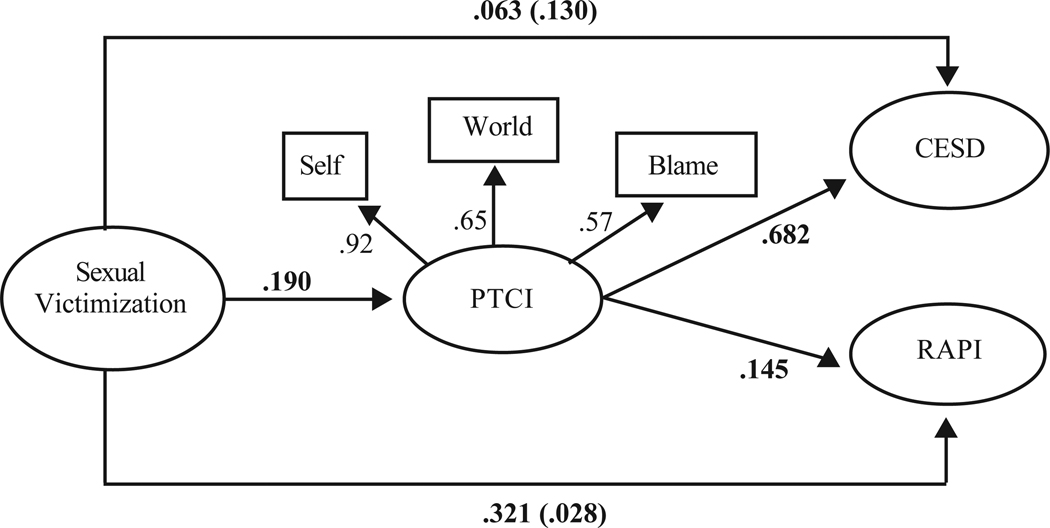

The first SEM tested the associations of sexual victimization, negative cognitions, depression, and alcohol consequences (Figure 1). The SEM demonstrated good fit to the data: χ2 (6, N=719) = 21.92, P<.001; CFI = 0.985; RMSEA = 0.061. Higher levels of sexual victimization predicted higher levels of negative cognitions (t=4.79), and higher levels of negative cognitions predicted higher levels of depression (t=16.88) and alcohol-related problems (t=3.76). The significant indirect effects of sexual victimization on both depression (t=4.57) and alcohol problems (t=2.94) provided support for the mediating role of negative cognitions. However, sexual victimization continued to have significant direct effects on depression (t=2.10) and alcohol problems (t=9.04), suggesting that their associations were not fully accounted for by negative cognitions.

Figure 1.

Structural Equation Model Depicting Mediating Role of Posttraumatic Cognitions in Associations Between Sexual Victimization with Depression and Alcohol-Related Negative Consequences

Note.

Standardized coefficients are reported. Numbers in parentheses are indirect effects. All coefficients are significant at P<.05 level.

The second SEM was similar in its specifications to the first except that 2 contrast-coded variables comparing nonvictims to victims of any type of sexual victimization and comparing nondating victimization to dating victimization were used as predictors. This SEM demonstrated good fit to the data: χ2 (10, n=719=P<0.001); CFI=0.945; RMSEA = 0.056. The first contrast (sexual victimization vs no sexual victimization) predicted higher levels of negative cognitions (t=3.34), and more negative cognitions predicted higher levels of depression (t=12.67) and alcohol problems (t=3.36). The direct and indirect effects of any sexual victimization were significant for alcohol problems (t=4.09 and t=2.40 respectively), but only the indirect effect was significant for depression (t=3.38). The victim-perpetrator relationship did not predict negative cognitions, but did have a direct effect on alcohol consequences (t=−3.51), with nondating sexual victimization being associated with more consequences.

DISCUSSION

Findings indicated that women who had been victimized reported more depression and alcohol-related negative problems than their counterparts did, and part of the reason for this was that they also had more negative cognitions. Both the direct and indirect effects of sexual victimization on the outcomes were significant, indicating that negative posttraumatic cognitions partially, but not fully, mediated the association of sexual victimization and the outcomes.

Our findings are consistent with prior research that has shown that the negative impact of trauma is due, at least partially, to posttraumatic negative cognitions.15,17,20,21 For example, among women experiencing partner violence, negative cognitive schemas pertaining to trust, self-esteem, perceived safety, and intimacy have been found to be significantly correlated with higher levels of posttraumatic stress and general psychological distress symptoms.31 Further, in a study comparing victims of violent crime to nonvictims, victims’ relatively higher levels of psychological distress was partially explained by their negative beliefs about safety, esteem, and trust. That is, victims’ increased risk for psychological distress is due to the negative impact the victimization experience has on their belief systems.17 Of particular relevance is a study that focused on college students. Among students who had experienced a traumatic event in their lifetimes, negative trauma-related cognitions were significantly associated with higher levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms.32

The type of victim-perpetrator relationship was not associated with cognitions. Although this finding was not what we expected, it may be that different types of cognitions are related differentially to the victim-perpetrator relationship. For example, perhaps women victimized by dating partners are more likely than women victimized by nondating partners to experience self-blame, but less likely than their counterparts to experience general fear and distrust of the world. Future research should examine if the type of victim-perpetrator relationship is differentially associated with different types of cognitions.

The study had some limitations that should be noted. The most serious limitation was that the data were cross-sectional. Therefore, we are not able to determine if sexual victimization resulted in changes in the level of negative cognitions. Prospective data are needed that would allow an examination of whether or not sexual victimization was related to changes in cognitions and if previctimization cognitions were associated with psychological and behavioral adjustment. Another study limitation was that the sample was fairly homogeneous (84% white, all first-year females). Thus, it is not known to what extent the findings would generalize to other populations, including upper-level college students and nonstudents. It also is not possible to examine either demographic differences in the prevalence of sexual victimization or differences in its associations with cognition and adjustment variables.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that offsetting negative cognitions following sexual victimization could help reduce victims’ risk for depression and alcohol-related negative consequences. A public health approach to developing interventions for violence against women includes (1) defining the problem and determining its magnitude; (2) identifying the causes of the problem; (3) designing, implementing, and evaluating interventions based on the identified causes; and (4) disseminating promising strategies.33 Our study findings can be used to inform the third step of this framework – designing interventions to address the variables found to be predictive of the onset and maintenance of psychological and behavioral problems associated with sexual victimization.

Our findings suggest that interventions with college females who have been sexually victimized need to include a focus on restructuring negative schemas a woman might have about herself, the world, and her relationship to it. An intervention approach based on the important role of cognitive processing has been used already in interventions with female assault survivors with PTSD34 Evaluation data indicated that providing women with exposure experiences that disconfirmed their negative posttraumatic cognitions helped to prevent posttrauma negative psychological consequences. Our findings suggest that this type of intervention approach could be extended to college students who are sexually victimized, regardless if the experience occurred in a dating context.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant to the first author from the National Institutes of Health (R15AA015687-01A2). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Martie P. Thompson, Center for Research and Collaborative Activities, Clemson University, Clemson, SC.

J. B. Kingree, Department of Public Health Sciences, Clemson University, Clemson, SC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sorenson SB, Stein JA, Siegel JM, et al. The prevalence of adult sexual assault: the Los Angeles epidemiologic catchment area project. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126(6):1154–1164. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55(2):162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher B, Cullen FT, Turner MG. The sexual victimization of college women. 2000. [Accessed October 4, 2008];U.S. Department of Justice, NIJ 182369. 2003 Available at: http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/182369.pdf.

- 4.Humphrey JA, White JA. Women’s vulnerability to sexual assault from adolescence to young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(6):419–424. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludermir AB, Schraiber LB, D’Oliveira A, et al. Violence against women by their intimate partner and common mental disorders. Soc Sc Med. 2008;66(4):1008–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson JR, Hughes DC, George LK, et al. The association of sexual assault and attempted suicide within the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(6):550–555. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830060096013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell JC, Soeken KL. Forced sex and intimate partner violence: effects on women’s risk and women’s health. Violence against Women. 1999;5(9):1017–1035. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(4):260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank E, Turner S, Duffy B. Depressive symptoms in rape victims. J Affect Disord. 1979;1(4):269–277. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(79)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taft CT, Resick PA, Panuzio J, et al. Coping among victims of relationship abuse: a longitudinal examination. Violence Vict. 2007;22(4):408–418. doi: 10.1891/088667007781553946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabina C, Straus MA. Polyvictimization by dating partners and mental health among US college students. Violence Vict. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.23.6.667. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnam MA, Stein JA, Golding JM, et al. Sexual assault and mental disorders in a community population. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):843–850. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, et al. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(5):834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larimer ME, Lydum AR, Anderson BK, et al. Male and female recipients of unwanted sexual contact in a college student sample. Prevalence rates, alcohol use, and depression symptoms. Sex Roles. 1999;40(3/4):295–308. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foa EB, Ehlers A, Clark DM, et al. The posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1999;11(3):303–314. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janoff-Bulman R. Assumptive worlds and the stress of traumatic events: applications of the schema construct. Soc Cogn. 1989;7(2):113–136. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norris FH, Kaniasty K. The psychological experience of crime: a test of the mediating role of beliefs in explaining the distress of victims. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1991;10(3):239–261. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piaget J. The Origins of Intelligence in Children. New York: International Universities Press; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalgleish T. Cognitive approaches to posttraumatic stress disorder: the evolution of multirepresentational theorizing. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(2):228–260. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koss MP, Figueredo J. Change in cognitive mediators of rape’s impact on psychosocial health across 2 years of recovery. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1063–1072. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCann IL, Pearlman L. Psychological Trauma and the Adult Survivor: Theory, Therapy, and Transformation. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gidycz CA, Van Wynsberghe A, Edwards KM. Prediction of women’s utlization of resistance stratgies in a sexual assault situation: a prospective study. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(5):571–588. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greene DM, Navarro RL. Situation-specific assertiveness in the epidemiology of sexual victimization among university women. Psychol Women Q. 1998;22(4):589–604. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA, et al. Assessing women’s experiences of sexual aggression using the sexual expereinces survey: evidence for validity and implications for research. Psychol Women Q. 2004;28(3):256–265. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 26.White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muthen LK, Muthen B. Mplus User’s Guide, Version 2. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmines E, McIver J. Analyzing models with unobserved variables: analysis covariance structures. In: Bohrnstedt G, Borgatta E, editors. Social Measurement: Current Issues. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 1981. pp. 65–115. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDonald RP, Ho MR. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dutton MA, Burghardt KJ, Perrin SG, et al. Battered women’s cognitive schemata. J Trauma Stress. 1994;7(2):237–255. doi: 10.1007/BF02102946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moser JS, Hajcak G, Simons RF. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in traumaexposed college students: the role of traumarelated cognitions, gender, and negative affect. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21(8):1039–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saltzman LE, Green YT, Marks J, et al. Violence against women as a public health issue: comments from the CDC. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(4):325–339. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foa EB Rauch SAM. Cognitive changes during prolonged exposure plus cognitive restructuring in female assault survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(5):879–884. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]