Abstract

A new Drosophila Pax gene, sparkling (spa), implicated in eye development, was isolated and shown to encode the homolog of the vertebrate Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 proteins. It is expressed in the embryonic nervous system and in cone, primary pigment, and bristle cells of larval and pupal eye discs. In spapol mutants, a deletion of an enhancer abolishes Spa expression in cone and primary pigment cells and results in a severely disturbed development of non-neuronal ommatidial cells. Spa expression is further required for activation of cut in cone cells and of the Bar locus in primary pigment cells. We suggest close functional analogies between Spa and Pax2 in the development of the insect and vertebrate eye.

Keywords: Pax2 homolog, eye development, sparkling, cone cells, primary pigment cells, Drosophila

The Drosophila compound eye is a hexagonal array of ∼750 facets or ommatidia, each of which consists of eight photoreceptor cells (R1–R8), four non-neuronal cone cells, three types of pigment cells, and bristle cells arranged in a stereotyped pattern (for review, see Wolff and Ready 1993). The fate of cells in the eye disc is determined during the progressive assembly of individual ommatidia, which is initiated in the morphogenetic furrow sweeping from posterior to anterior across the eye disc during the third larval instar and early pupal stage. Undifferentiated cells are recruited in a fixed sequence to adopt a particular developmental fate based on temporally and spatially restricted signals from previously recruited neighboring cells (for reviews, see Dickson and Hafen 1993; Zipursky and Rubin 1994). In late third instar larvae and early pupae, after the assembly of the eight photoreceptor cells, the four cone cells are recruited into each growing ommatidium. In early pupae, anterior and posterior cone cells induce their neighboring undifferentiated cells to become primary pigment cells (Cagan and Ready 1989). Subsequently, secondary and tertiary pigment cells are incorporated into each ommatidium, followed by elimination of all surplus cells through programmed cell death (Wolff and Ready 1993). Incorrect determination of these cell fates disrupts the ommatidial assembly, leading to a rough appearance of the adult eye as a consequence of irregularly spaced ommatidia.

The retinal precursor cells are recruited by signals that emanate from already differentiating ommatidial cells and that activate the Ras signaling pathway (for review and model, see Freeman 1997). It appears that these signals play a permissive rather than an instructive role (Dickson et al. 1992): They trigger the differentiation of recruited cells in a time-dependent manner as cell fate hinges critically on the specific set of susceptible transcription factors present, whose activity states are modified by selective phosphorylation in response to the signal (Freeman 1997). As a result, these transcription factors activate genes, some of which also encode transcription factors that determine the next steps of a cell’s developmental pathway. Therefore, it is important to identify transcription factors that are expressed differentially in ommatidial cells. While a number of such factors have been characterized to be essential for the correct determination of photoreceptors (for review, see Dickson 1995), relatively few genes are known that encode transcription factors required for the specification of the subsequently recruited cone and pigment cells.

Two genes encoding paired-domain transcription factors, Pax2 and Pax6, have been shown to play crucial roles in vertebrate eye development (for review, see Macdonald and Wilson 1996). Homozygous Sey mice, which are deficient for Pax6 activity, develop no eyes because they fail to initiate retinal development. In Pax2 null mutant mice, no glial cells develop in the optic nerve, and the optic chiasma fails to form as all retinal axons project ipsilaterally, which indicates that Pax2 is required for proper guidance of the retinal axons along the optic stalk and across the ventral diencephalon (Torres et al. 1996). In addition, the optic fissure fails to close in these mice, which produces optic nerve coloboma (Torres et al. 1996). In agreement with the mutant phenotypes, Pax6 is expressed in the optic cup, whereas Pax2 expression is restricted to the optic stalk epithelium from which all glial cells of the optic nerve develop. Thus, in wild-type eyes Pax6 and Pax2 expression is mutually exclusive, which results in a sharp boundary between eye and optic stalk, whereas in the absence of Pax2, Pax6 expression extends from the pigmented retina into the optic stalk epithelium, causing it to differentiate into pigmented retina instead of glial cells (Torres et al. 1996). Although Pax6 plays an essential role in the initiation of eye development in Drosophila (Quiring et al. 1994; Halder et al. 1995a) and probably all metazoa (Halder et al. 1995b), as yet no Pax2 homolog has been identified in invertebrates (Macdonald and Wilson 1996). Because evolution tends to conserve networks of functionally related genes (Noll 1993), it was logical to postulate that, in addition to the Pax6 homolog eyeless (ey) (Quiring et al. 1994), a homolog of the Pax2, Pax5, Pax8 subgroup existed in Drosophila and played a conserved role in eye development.

Indeed, as we report here and show by isolation and molecular characterization, the paired-box gene sparkling (spa) is the Drosophila homolog of the mammalian Pax2 gene. In addition to its structural conservation, spa appears to be conserved functionally in eye development. It is required for proper specification and differentiation of cone and primary pigment cells. Spa may partly exert its function through the activation of cut in cone cells and of both Bar genes in primary pigment cells.

Results

Isolation of a cDNA whose expression is altered in spa mutant eye discs

To complement our attempts to isolate additional Drosphila Pax genes from a genomic library by low stringency hybridization (Noll 1993), we took advantage of a cross-reacting antiserum directed against the Drosophila Pax protein Pox meso (Poxm) (Bopp et al. 1989). This antiserum reacted not only with segmentally repeated mesodermal antigens but also with antigens of the developing peripheral and central nervous system (PNS and CNS), which were also expressed in a segmentally repeated pattern (Fig. 1A). Because the staining of the PNS and CNS remained unaltered in homozygous Df(3R)dsxD+R5 embryos (Fig. 1B), in which the poxm gene at 84F11-12 is deleted (Bopp et al. 1989), the antigens revealed in the nervous system must be different from Poxm. As the expression pattern of the cross-reacting antigen did not correspond to any of those of known Drosophila Pax genes (Noll 1993), it was reasonable to assume that it belonged to a hitherto unknown Pax protein, possibly the Pax2 homolog. To test this possibility, we screened a cDNA expression library, derived from 4- to 8-hr-old embryos, with the anti-Poxm antiserum and isolated a single 3.8-kb cDNA, cpx1, that did not originate from poxm but from a locus at 102F1-2. As expected, when Df(4)G embryos, deficient for this chromosomal region, were stained with anti-Poxm antiserum, they displayed only the Poxm-specific mesodermal pattern, whereas no cross-reacting antigen was detectable (Fig. 1C). In addition, in situ hybridization of embryos with a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled cpx1 probe (Fig. 1D) showed the same expression pattern as the cross-reacting antigen (Fig. 1B). The lack of detectable signal after hybridization of the same probe to homozygous Df(4)G embryos (not shown) corroborated that cpx1 was derived from a gene located at 102F1-2.

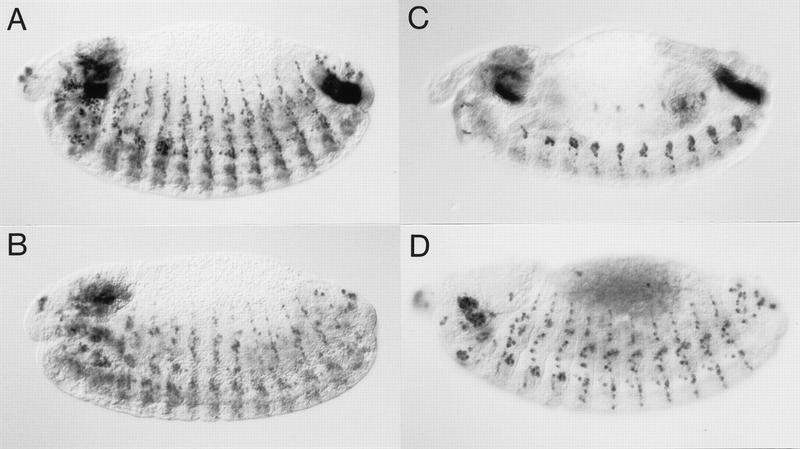

Figure 1.

Cross-reactivity of anti-Poxm antiserum. A heterozygous Df(3R)dsxD+R5 embryo (A), a homozygous Df(3R)dsxD+R5 embryo (B), and a homozygous Df(4)G embryo (C) were probed with the anti-Poxm antiserum to demonstrate the cross-reactivity of the antiserum in embryos lacking the poxm locus (B) or the locus of the cross-reacting antigen (C). A wild-type embryo (D) was hybridized in situ with a digoxigenin-labeled cpx1 cDNA, which encodes the cross-reacting antigen and was isolated by immunoscreening a cDNA expression library with the anti-Poxm antiserum. Lateral views of stage 13 embryos are shown with their anterior to the left and their dorsal sides up.

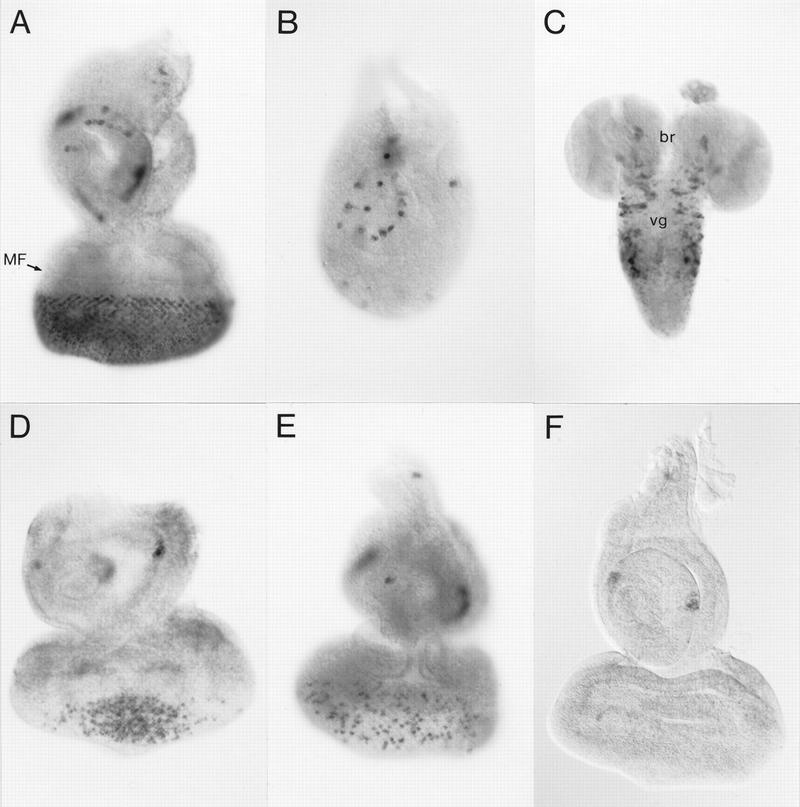

Expression of the gene encoding cpx1 was further examined in the imaginal discs and CNS of third instar larvae. As shown in Figure 2A, cpx1 transcripts are expressed in the posterior portion of the eye disc, with the anterior boundary of expression lagging clearly behind the morphogenetic furrow. In addition, isolated cells of the antennal (Fig. 2A), leg (Fig. 2B), and wing discs (not shown) exhibit strong expression. In the CNS, expression is observed mainly in the thoracic ventral ganglion and in the brain (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Expression patterns of cpx1 in wild type and spa mutants. A wild-type third instar larval eye–antennal disc (A), leg disc (B), and ventral ganglion with brain (C; ventral view) were hybridized with a digoxigenin-labeled cpx1 cDNA. The expression pattern of cpx1 in a wild-type third instar larval eye–antennal disc was compared to that in corresponding discs of homozygous spa1 (D), heterozygous spaA (E), and homozygous spapol mutants (F), using the same DNA probe. (br) Brain; (MF) morphogenetic furrow; (vg) ventral ganglion.

Of the six lethal loci and two recessive visibles that are uncovered by the terminal deficiency Df(4)G (Hochman 1971), only spa shows an eye phenotype; hence, cpx1 might originate from this gene. All spa mutants have rough eyes. The strongest spa alleles also produce unpigmented tarsal claws (Lindsley and Zimm 1992), whose precursor cells are located in the center of leg discs and also appear to express cpx1 transcripts (Fig. 2B). To test whether cpx1 was derived from spa, we examined whether cpx1 expression was affected in late third instar eye–antennal discs of several spa mutants. Indeed, expression is reduced in the weak homozygous spa1 mutant eye disc, or even abolished in dorsal and ventral regions (Fig. 2D). In the dominant mutant spaA/+, cpx1 expression appears mottled, apparently because this dominant allele is able to silence expression of the wild-type spa allele in a manner reminiscent of transvection and position effect variegation (Fig. 2E). It might be significant that the spaA mutation is associated with a translocation T(3;4)UbxA between Ubx and spa (Lindsley and Zimm 1992). Finally, in the strong homozygous spapol mutant, no cpx1 transcript is detectable in the larval eye disc and only few cells express it in the antennal disc (Fig. 2F), whereas its expression is strongly reduced in the center of the leg disc (not shown). These results suggest that cpx1 is derived from the spa gene.

Identification and transcriptional organization of the spa gene

To prove that cpx1 originates from spa, we mapped the exons of cpx1 on the genomic DNA and identified the molecular lesions in the cpx1 transcription unit of two spontaneously induced alleles spa1 and spapol. Using cpx1 as probe, we isolated additional cDNAs from embryonic and disc libraries and the corresponding genomic clones from a λ phage library. Mapping all cDNAs with respect to the genomic DNA by sequencing showed that the longest spa cDNAs consisted of 13 exons, spanning a genomic region of 24 kb (Fig. 3A). The corresponding genomic DNAs of homozygous spa1 and spapol flies exhibited rearrangements characteristic of spontaneously induced mutations. Thus, the spapol mutation is a 1.58-kb deficiency, which removes exons 3 and 4 and flanking sequences, whereas spa1 consists of a 7.5-kb insertion into the same region of intron 4 (Fig. 3A). Because the cpx1 transcript fails to be expressed in third instar eye discs of spapol mutants (see Fig. 2F), these findings further demonstrate that the spapol deletion removes an essential portion of the spa eye disc enhancer. This conclusion was confirmed by experiments, in which the spapol phenotype was rescued completely in a transgenic fly stock by the expression of Spa under the control of its own promoter and enhancer sequences of intron 4 (see Materials and Methods). Deletion of exons 3 and 4 does not result in a frameshift and hence has no apparent effect on the expression of the Spa protein in homozygous spapol embryos or in bristle cells of spapol pupal eye discs (not shown, but see below).

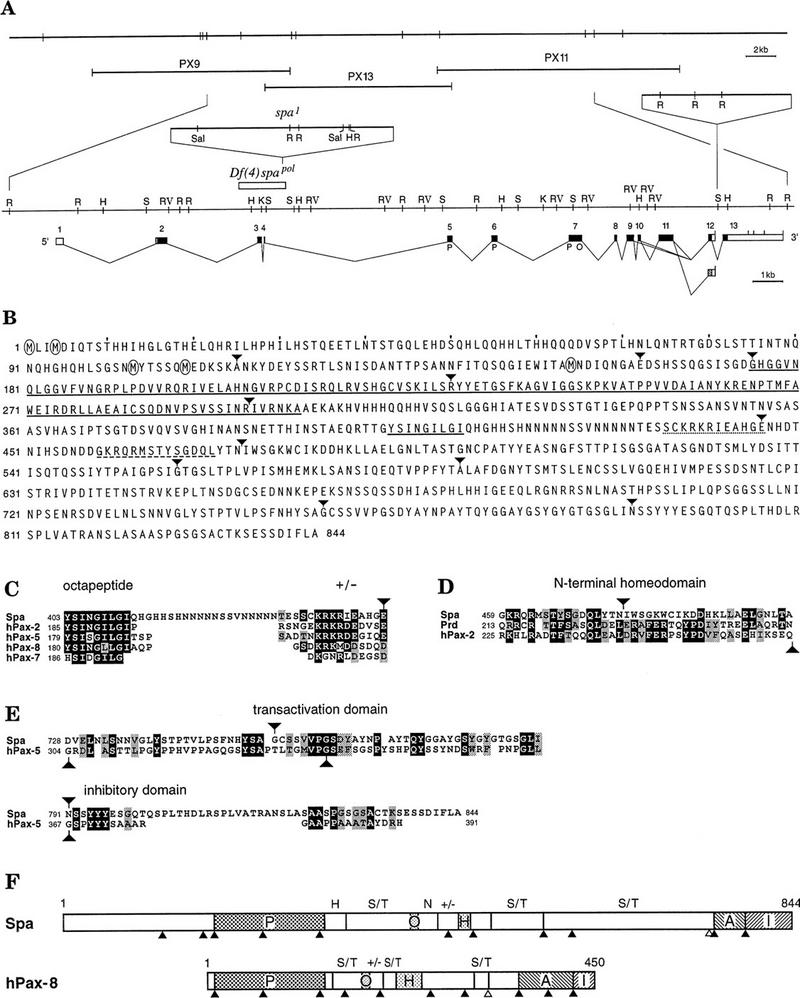

Figure 3.

Structural organization of the spa locus and deduced sequence and conserved domains of the Spa protein. (A) The spa locus is shown with respect to a genomic EcoRI map at the top and three overlapping inserts from a λ DASH II genomic library below. Underneath, an enlarged detailed restriction map of the genomic region spanning the spa transcript is shown, above which two spa mutations, the spa1 insertion and the spapol deficiency, and an insertion polymorphism in intron 12 are indicated. Below the restriction map, the intron–exon structure and the open reading frame (in black; with paired domain P and octapeptide O) corresponding to the longest spa cDNAs from embryos and third instar larvae are depicted, and different splice variants are indicated. In third instar larvae, only two splice variants, which differed with respect to the presence or absence of exon 11, were detected by reverse transcriptase PCR amplification of total disc RNA. Both used the poly(A) addition site in intron 12 and therefore, lacked the putative inhibitory domain encoded by exon 13. Occasionally, an alternative 3′ splice acceptor site of intron 9 is used, resulting in the in-frame deletion of the first two amino acids encoded by exon 10. Abbreviations of restriction sites: (H) HindIII; (K) KpnI; (R) EcoRI; (RV) EcoRV; (S) SpeI; (Sal) SalI. (B) The deduced amino acid sequence of the longest open reading frame encoded by spa cDNAs with encircled methionines indicating the positions of the five potential initiators preceding the paired domain. Underlined are the paired domain and octapeptide by solid lines, a conserved highly charged dodekapeptide by a dotted line, and a peptide homologous to the amino terminus of a homeodomain by a dashed line. (C–E) The conservation of the octapeptide and highly charged dodekapeptide sequences (C), of the fractional homeodomain sequences (D), and of the carboxy-terminal transactivation and inhibitory domains of Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 and Spa (E). (F) The conservation of domains and positions of introns in Spa and Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 proteins. The position of introns are indicated by filled triangles, alternative splice sites by open triangles in Spa and human Pax8. In addition to the paired domain (P), octapeptide (O), amino-terminal portion of a homeodomain (H), transactivation domain (A), and inhibitory domain (I), Ser/Thr-rich domains (S/T), Gln-rich domains (N), and highly charged regions (+/−) are indicated.

The spa gene encodes the homolog of the vertebrate Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 proteins

Sequencing of the isolated spa cDNAs revealed a long open reading frame of 844 amino acids, extending from exon 2 to exon 13 (Fig. 3A). As anticipated, the Spa protein includes a paired domain of 128 amino acids (Fig. 3B). Surprisingly, the paired domain is preceded by a relatively long amino-terminal peptide of 174 amino acids, whereas all known paired domains are located much closer to the amino terminus (Noll 1993). Even the use of the best translational start consensus sequence (Cavener 1987), found at the third of the five methionine codons preceding the paired domain (Fig. 3B), would result in an unusually long 72-amino-acid peptide preceding the paired domain.

The paired domain of Spa is clearly the closest Drosophila relative of the vertebrate Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 paired domains, displaying 88% identity and 91% similarity to the paired domains of mouse or human Pax2 (Table 1). The closest Drosophila relative of the Spa paired domain, the Ey paired domain, exhibits only 73% identity and 84% similarity to the Pax2 paired domain. Additional domains of the Spa protein possess homologous counterparts in the vertebrate Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 proteins. Thus, the octapeptide, present in most Pax proteins (Noll 1993), is extended to a nonapeptide identical to that of Pax2 and closely linked to a highly charged dodecapeptide conserved in Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 (Fig. 3C). In addition, the amino-terminal portion of a prd-type homeodomain, characteristic of Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 (Krauss et al. 1991), has been conserved in Spa although its conservation extends only over 14 instead of 31 amino acids in Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 (Fig. 3D). Most interestingly, a transactivation domain and its inhibitory domain found at the carboxyl terminus of Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8, but in no other Pax proteins (Dörfler and Busslinger 1996), have also been conserved at the carboxyl terminus of Spa (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, Spa and Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 include three Ser/Thr-rich regions at roughly equivalent positions that also may serve as transactivation domains (Fig. 3F; Kozmik et al. 1993). Finally, Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 and Spa have conserved precisely the locations of introns within the paired domain and between the transactivation and inhibitory domain (Kozmik et al. 1993; Sanyanusin et al. 1995; Busslinger et al. 1996; Dörfler and Busslinger 1996). Hence, Spa may be considered the Drosophila homolog of Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8 (Fig. 3F).

Table 1.

Matrix of sequence conservation among paired domains of Drosophila and human/mouse Pax genes

| Pax2 | 0.88 | ||||||||||||||

| 0.91 | |||||||||||||||

| Pax5 | 0.87 | 0.98 | |||||||||||||

| 0.91 | 0.99 | ||||||||||||||

| Pax8 | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.94 | ||||||||||||

| 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.98 | |||||||||||||

| ey | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.72 | |||||||||||

| 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | ||||||||||||

| Pax6 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.95 | ||||||||||

| 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.95 | |||||||||||

| poxm | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.70 | |||||||||

| 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.75 | ||||||||||

| Pax1 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.88 | ||||||||

| 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.92 | |||||||||

| Pax9 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.88 | 0.96 | |||||||

| 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.97 | ||||||||

| prd | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.66 | ||||||

| 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | |||||||

| gsb | 0.61 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.82 | |||||

| 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.88 | ||||||

| gsbn | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 0.82 | ||||

| 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.90 | 0.88 | |||||

| Pax3 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.77 | |||

| 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.88 | ||||

| Pax7 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.94 | ||

| 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.96 | |||

| poxn | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.66 | |

| 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.75 | ||

| Pax4 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.57 |

| 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.70 | |

| spa | Pax2 | Pax5 | Pax8 | ey | Pax6 | poxm | Pax1 | Pax9 | prd | gsb | gsbn | Pax3 | Pax7 | poxn |

The fractions of identical (upper number) and similar (lower number) amino acids among paired domains of the Drosophila genes spa, ey, poxm, paired (prd), gooseberry (gsb), gooseberry neuro (gsbn), and pox neuro (poxn) and the human or mouse genes Pax1 to Pax9 are shown.

In addition to its protein structure, spa has conserved a pattern of differential splicing and protein isoforms reminiscent of that observed for Pax8 (Kozmik et al. 1993). In the 3′ portion of the spa transcript, alternative splice products are generated, in which exon 11 or exons 10 and 11 are skipped (Fig. 3A), producing in-frame deletions of the Ser/Thr-rich region that precedes the carboxy-terminal transactivation and inhibitory domains. This Spa isoform is very similar to those of human and mouse Pax8b, which lack exon 8 and therefore, also part of the Ser/Thr-rich region preceding the carboxy-terminal transactivation and inhibitory domains (Kozmik et al. 1993). In another splice variant of the spa transcript, an alternative 3′ acceptor site is used in intron 11, preceding the most frequently used site by 17 nucleotides and thus generating a frameshift and premature termination at the end of exon 12 (Fig. 3A). Hence, the resulting Spa protein lacks the conserved transactivation and inhibitory domains as do the Pax8 isoforms of the human Pax8c,d splice variants (Kozmik et al. 1993).

The splicing process of spa transcripts is also affected by differential poly(A) addition. In addition to four poly(A) addition sites found in the noncoding trailer of exon 13, three closely spaced poly(A) addition sites, preceded by AATGAA and AATATA, are located about 100 nucleotides downstream of the 5′ splice donor site of intron 12, preventing its splicing (Fig. 3A). Provided that the transactivation and inhibitory domains (Kozmik et al. 1993) have also been conserved functionally in Spa, the resulting truncated Spa protein would be constitutively active as the transactivation domain is retained, whereas the carboxy-terminal inhibitory domain encoded by exon 13 is replaced by two amino acids of intron 12 (Fig. 3E,F). Although no such differential poly(A) addition has been observed for Pax2, Pax5, and Pax8, the Pax8c and/or Pax8d splice variants, in which the transactivation and inhibitory domains are replaced by proline-rich domains (Kozmik et al. 1993), might represent evolutionary variants that execute similar functions.

Localization of Spa protein in nuclei of cone cells, primary pigment cells, and bristle cells

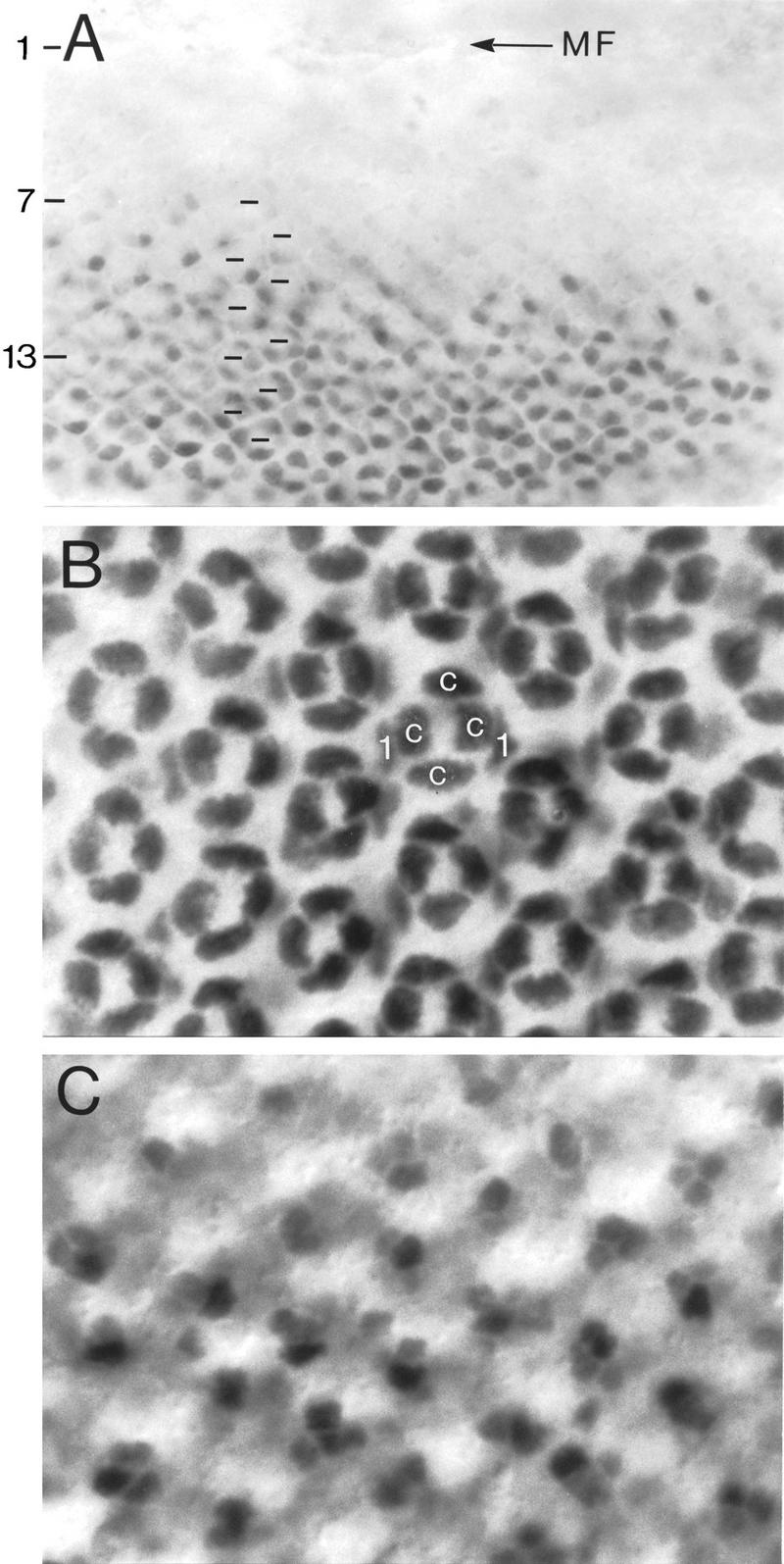

In the developing eye, spa transcripts are first detectable in eye discs of late third instar larvae (see Fig. 2A). Staining such discs histochemically with an anti-Spa antiserum reveals that the anterior margin of Spa expression lags six to seven rows of ommatidial precursors behind the morphogenetic furrow (Fig. 4A), in which the assembly of ommatidia begins (Wolff and Ready 1993). Five rows behind the furrow, the assembly of the eight photoreceptor precursors is complete and the accretion of the future anterior and posterior cone cells first becomes apparent in row 6, whereas a few rows more posterior, the polar and equatorial cone cells are added to the ommatidia (Wolff and Ready 1993). At this stage, the Spa protein is localized exclusively in the nuclei of all four cone cell precursors (Fig. 4A). Thus, expression of Spa in cone cell precursors begins very shortly after their accretion to the growing ommatidial clusters. During early pupal stages, Spa is also found in the nuclei of primary pigment cell precursors (Fig. 4B), which are recruited to the developing ommatidia at this time. In addition, Spa appears in the basally located nuclei of mechanosensory bristle cells (Fig. 4C), which in contrast to all other ommatidial cells are derived clonally from a bristle mother cell at this stage (Wolff and Ready 1993). At no time did we find Spa to be expressed in immature or differentiated photoreceptor cells or secondary and tertiary pigment cells.

Figure 4.

Localization of Spa protein in nuclei of cone, primary pigment, and bristle cells of the developing eye. Spa protein is observed in cone cells of a third instar larval eye disc (A). In a 24-hr pupal eye disc (B,C; dorsal side up), Spa remains detectable in nuclei of cone cells and appears in nuclei of primary pigment cells (B) and bristle cells (C). Horizontal marks in A indicate the regular spacing of the centers of stained hexagonal ommatidial rows 7–16 behind the morphogenetic furrow (MF). The number of ommatidial rows behind the morphogenetic furrow was assessed independently by double-staining for Armadillo, which outlines the growing ommatidial clusters, and Spa and subsequent confocal microscopy (not shown). (B) A more apical optical section than the basal section shown in C. (c) Cone cell; (1) primary pigment cell.

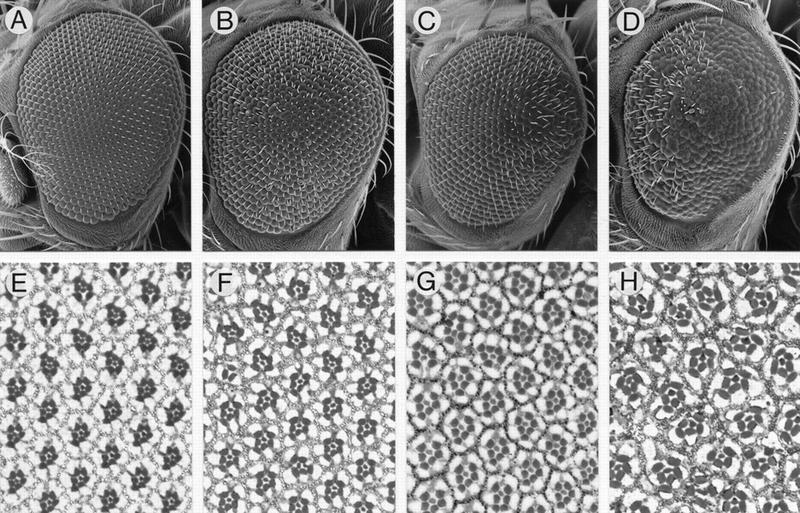

Disrupted surface structure and underlying cellular pattern in spa mutant eyes

To investigate the role of spa in eye development, we compared the external eye phenotype of spa mutants to that of the wild type by scanning electron microscopy (Fig. 5A–D). In wild-type flies, the adult compound eye displays a regular hexagonal array of facets with mechanosensory bristles projecting from alternate facet vertices, usually at the anterior end of each horizontal hexagonal edge (Fig. 5A). Homozygous spa1 adults have a variable rough eye phenotype, which is more extreme at 18°C than at 25°C (Lindsley and Zimm 1992). Eyes of spa1 mutants grown at 18°C reveal many ommatidia with defective corneal lenses and pseudocones, occasionally fused facets, and frequently mispositioned bristles or two bristles protruding from the same vertex, an effect that is most pronounced dorsally and ventrally (Fig. 5B). The external eye phenotype of the dominant spaA/+ mutant is similar to, but less extreme than that of spa1 mutants raised at 18°C, and largely restricted to the posterior portion of the eye (Fig. 5C), whereas it is stronger than that of spa1 mutants grown at 25°C (not shown). The strongest phenotype is clearly exhibited by spapol flies whose eye size is somewhat reduced (Fig. 5D). Their corneal lenses and pseudocones, which are secreted by the cone cells and primary pigment cells, are blurred and irregular, and many of them are fused (Rickenbacher 1954; Oster and Crang 1972; Stumm-Tegethoff and Dicke 1974). In addition, numerous necrotic pits are apparent between an irregular array of ommatidia of variable size. Although initially present, nearly all bristles in the posterior of the eye have broken or fallen off during the first 3 days after eclosion, whereas most bristles in the anterior are misplaced or project as doublets from the same vertex (Fig. 5D; Rickenbacher 1954).

Figure 5.

Disrupted surface structures of spa mutant eyes caused by a disorganized underlying cellular pattern. Scanning electron micrographs of left eyes (A–D) and corresponding histological sections displaying the underlying ommatidial patterns (E–H) of 3-day-old wild-type flies (A,E) are compared to those of 3-day-old homozygous spa1 (B,F), spaA/+ (C,G), and homozygous spapol flies (D,H). Each eye (whole mount or section) is shown with its anterior to the left and dorsal side up.

The regular array of wild-type facets is a direct manifestation of a precise, underlying cellular lattice of ommatidia, whose orientations in the dorsal and ventral halves of the eye exhibit mirror symmetry with respect to a horizontal equator as evident from histological sections (Fig. 5E). To test whether the disturbed surface structures observed in spa mutants is the reflection of an altered underlying cellular pattern, sections of spa mutant eyes were examined (Fig. 5F–H). In the spa1 retina, most ommatidia appear wild type. However, in ∼15% of the ommatidia the number of photoreceptors is reduced or their orientation and types are abnormal (Fig. 5F). Similarly, in spaA mutants some ommatidia have an altered number of photoreceptors (Fig. 5G). The retinal phenotype of spapol mutants is most severe (Fig. 5H), as expected, in which the entire retina is disorganized, which is further enhanced with age. Although many ommatidia of young adults have retained eight photoreceptors, their orientation and positions are disturbed, most rhabdomeres are malformed, and frequently the ommatidia appear fused to each other. Some ommatidia have also lost two to five photoreceptor cells.

Clearly, the external eye phenotype of spa mutants is the result of a disrupted underlying cellular pattern. Because spa is never expressed in wild-type photoreceptors or their precursors, we conclude that the altered photoreceptor phenotype of spa mutants is a secondary effect, probably resulting from a reduced expression of spa in the precursors of cone cells whose thin cytoplasmic extensions interdigitate between the photoreceptor cells (Wolff and Ready 1993).

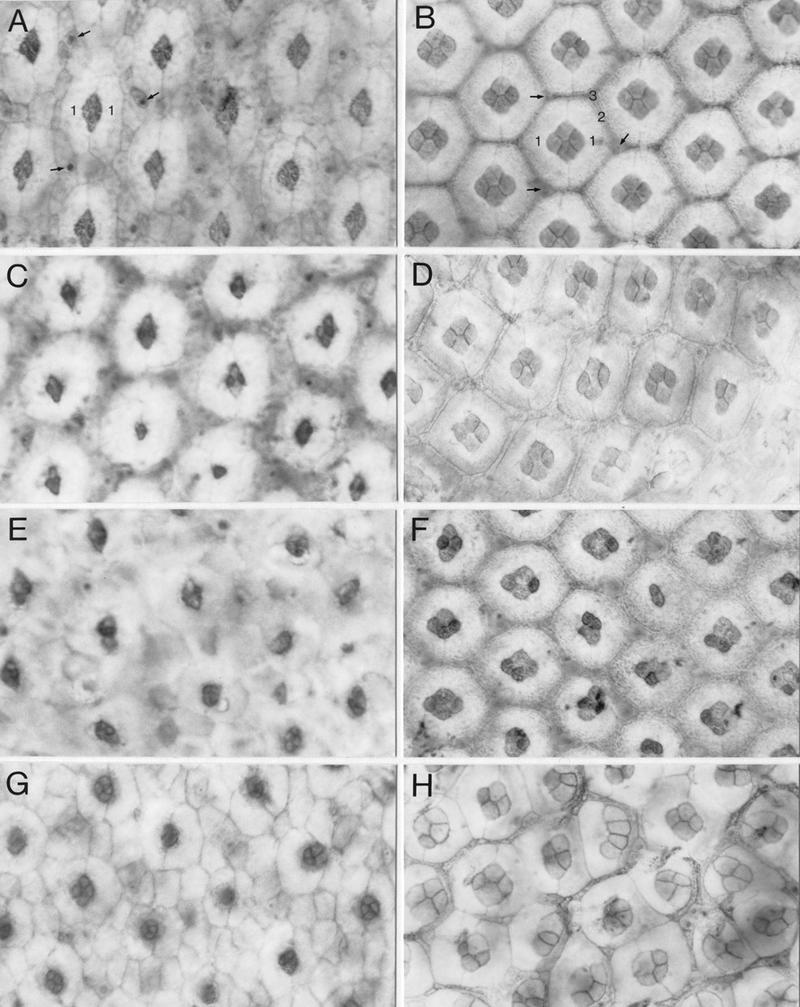

Abnormal development of cone and pigment cells in spapol mutants

As spa is expressed in the precursors of cone cells, primary pigment cells, and bristle cells, we expect to observe in these cells a more direct effect of spa mutations on eye development. Cone cells begin to assemble with the maturing ommatidia 6–11 rows behind the morphogenetic furrow in late third instar eye discs, whereas pigment and bristle cells are recruited only during the first third of pupal life, thereby completing ommatidial assembly (Wolff and Ready 1993). Therefore, we compared the apical retinal surface of wild type and spa mutants during and after completion of ommatidial assembly, 24 and 45 hr after puparium formation (APF) at 25°C (Fig. 6). In 24-hr wild-type pupal eye discs (corresponding to 40 hr pupal discs at 20°C; Wolff and Ready 1993), the two primary pigment cells have enlarged and wrapped around the four cone cells, touching each other at the dorsoventral boundaries, whereas the polar and equatorial cone cells have moved to contact each other apically and separate the anterior and posterior cone cells, with which they display an elongated rhomboid-like configuration (Fig. 6A). At 45 hr APF, the cone and primary pigment cells have expanded their apical profiles, constraining the secondary and tertiary pigment cells into a necklace-like array, and surplus cells have been eliminated (Fig. 6B; Wolff and Ready 1993).

Figure 6.

Abnormal development of cone and pigment cells in spa mutants. Early (24 hr APF at 25°C; A,C,E,G) and mid-pupal (45 hr APF at 25°C; B,D,F,H) eye discs of wild-type (A,B), homozygous spa1 (C,D), spaA/+ (E,F), and homozygous spapol (G,H) flies were stained with cobalt sulfide to visualize their cone and pigment cells at the apical surface of the retina. Examples of primary (1), secondary (2), and tertiary (3) pigment cells and of bristle cells (arrows) are marked in wild-type discs. Discs are shown with their anterior to the left and dorsal side up.

The apical pattern of cone and primary pigment cells is only slightly disturbed in 24- and 45-hr pupal discs of spa1 mutants when they were raised at 25°C (Fig. 6C,D), which is consistent with earlier observations that the spa1 phenotype is less severe at 25°C than at 18°C (Lindsley and Zimm 1992). A few ommatidia have lost one cone cell, whereas their primary pigment cells appear to be normal (Fig. 6D). In spaA mutants, the ommatidia are abnormal only in the posterior portion of the pupal retina (Fig. 6E,F). At the early pupal stage, the four cone cells frequently fail to assemble in the typical rhomboid-like configuration (Fig. 6E), whereas after completion of ommatidial assembly one or two cone cells or one of the primary pigment cells may be missing (Fig. 6F). In the latter case, a single primary pigment cell expands beyond its normal dorsoventral boundaries and attempts to encircle all four cone cells.

The same phenotype, but more extreme, is observed in pupal discs of spapol mutants (Fig. 6G,H). At 24 hr APF, the cone cells retain their immature round shape and fail to adopt the rhomboid-like configuration, and some ommatidia lack one of the primary pigment cells (Fig. 6G). At 45 hr APF, most of the assembled ommatidia are disorganized and their regular lattice is disrupted (Fig. 6H). Although occasionally one cone cell is lost, usually all four cone cells are present but display abnormal sizes and shapes and have failed to form the proper contacts among each other, an effect that is most extreme in ommatidia where only one primary pigment cell is present. Moreover, about half of the ommatidia have lost one of the two primary pigment cells and the remaining primary pigment cell has enlarged and may enclose three of the four cone cells (Fig. 6H). In this case, usually a cell much thinner than a primary pigment cell assumes the position of the second primary pigment cell, but acquires few or no characteristics of a primary pigment cell.

Frequently, no cells remain between primary pigment cells of adjacent ommatidia (Fig. 6H). Thus, it is conceivable that further recruitment of secondary and tertiary pigment cells fails to occur in spapol mutants, whereas these cells appear to develop normally in the spa hypomorphs examined (Fig. 6D,F). Clearly, the abnormal development of cone and primary pigment cells in spapol mutants exerts secondary effects on the recruitment and/or development of the interommatidial secondary and tertiary pigment cells. As evident from the external adult phenotype (see Fig. 5D), many ommatidial bristle cells are misplaced in spapol mutants (Fig. 6H). This effect is not attributable to the lack of Spa protein in bristle cells, as Spa remains expressed in these cells (not shown). Rather, it is also a secondary effect resulting from the disturbed development or absence of primary, secondary, and tertiary pigment cells, which are probably required to constrain and assign proper positions to the bristle cells and to support their differentiation by intercellular signals (Higashijima et al. 1992a).

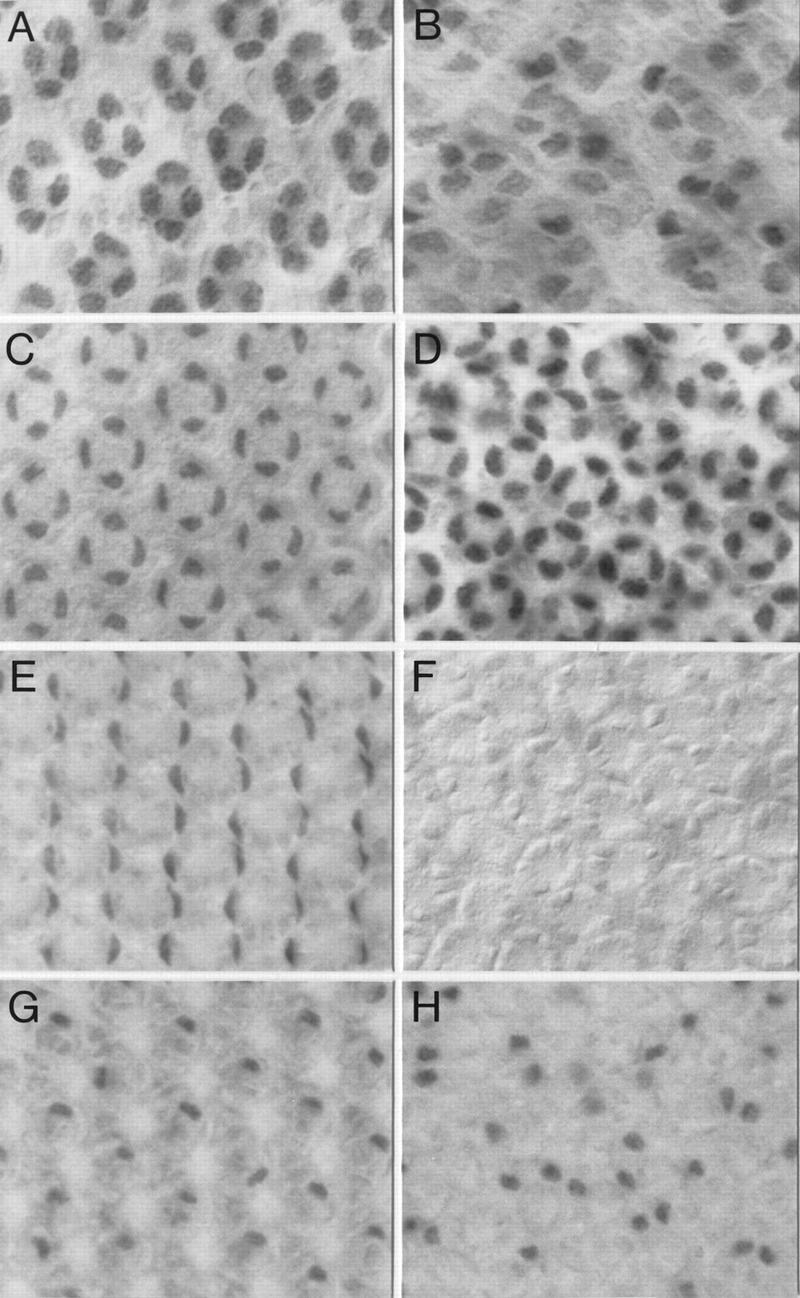

Altered expression of Cut and Bar in cone cells and primary pigment cells of spapol mutants

That cone cells and primary pigment cells develop abnormally in spapol mutants was also demonstrated by the effects of loss of Spa function on the expression of the cell markers Cut, which is expressed specifically in cone and bristle cells (Blochlinger et al. 1993; Dickson et al. 1995), and the two redundant homeodomain proteins, BarH1 and BarH2, whose expression is restricted to primary pigment cells and the glial and neural bristle cells at the pupal stages examined (Higashijima et al. 1992a,b). In 24-hr pupal discs, Cut expression is strongly reduced in cone cells of spapol mutants (Fig. 7B) compared to wild type (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, Cut expression recovers and rises even above wild-type levels 45 hr after pupariation (Fig. 7C,D). The lack of Spa protein in cone cells appears to delay the development of the cells as the shape of their nuclei and the nuclear accumulation of Cut (Fig. 7D) resemble those of earlier stages in wild-type pupal discs (Fig. 7A). This delay may be caused by a late larval and early pupal requirement of Spa for cut activation, which later becomes independent of Spa. Expression of cut in bristle cells, many of which are mispositioned, appears unaffected during these stages.

Figure 7.

Loss of Spa function affects expression of Cut and Bar proteins in cone and primary pigment cells of the eye disc. Cut expression in cone cells of a spapol (B), as compared to a wild-type (A), early pupal eye disc (24 hr APF at 25°C) is reduced. However, Cut expression in cone cells of a spapol mid-pupal eye disc (45 hr APF at 25°C; D) recovers and increases above the level observed in a wild-type mid-pupal eye disc (C). Bar expression in primary pigment cells of a wild-type (E) was also compared to that of a spapol (F) mid-pupal eye disc. Unlike the loss of its expression in primary pigment cells, Bar protein levels appear unaffected in bristle cells of a spapol (H) when compared to that of a wild-type mid-pupal eye disc (G). Note that the S12 anti-BarH1 antiserum used recognizes both BarH1 and BarH2 proteins (Higashijima et al. 1992b).

Expression of both Bar proteins in primary pigment cells (Fig. 7E) is abolished completely in spapol mutants (Fig. 7F). However, it remains unaffected in the irregularly positioned bristle cells (Fig. 7G,H), which continue to express Spa protein (not shown). Previous studies have shown that Bar is required for proper development of primary pigment cells as their numbers appear to decrease when both Bar genes are deleted (Higashijima et al. 1992a). Hence, Spa exerts at least part of its control of primary pigment cell development through its regulation of Bar expression. It is of interest that Bar is also expressed in R1 and R6 precursor cells (Higashijima et al. 1992a), where Lozenge (Lz) rather than Spa is one of its activators (Daga et al. 1996). This is another illustration of the combinatorial principle by which transcription factors determine cell fates.

Discussion

Essential role of Spa in the development of nonphotoreceptor cells of the eye

In search for additional Drosophila Pax genes, we identified the spa gene, discovered by Lilian Morgan in 1934 (Morgan 1947), as an invertebrate homolog of Pax2, Pax5, Pax8. We have also shown that the spa gene, similar to its mouse and human homolog Pax2, is important in eye morphogenesis. In particular, spa is expressed in cone and primary pigment cells for whose proper differentiation it is required. This is evident from spapol mutants, which display the most severe eye phenotype, resulting from the deletion of a specific enhancer that completely eliminates spa transcription in cone and primary pigment cells. In contrast, expression of Spa in bristle cells remains unaffected in spapol mutants, which indicates that it is controlled by a separate enhancer and thus supports the view that the mechanosensory bristles of the eye are developmentally distinct from other ommatidial cells (Wolff and Ready 1993).

In the absence of Spa, the development of cone and primary pigment cells is severely disturbed. Their shapes are altered, their interactions with each other and other ommatidial cells are irregular, and even their number is frequently reduced, which amplifies the disorganization among ommatidial cells. The loss of characteristically shaped primary pigment cells is much more pronounced than the loss of cone cells. Because undifferentiated cells that contact the anterior and posterior cone cells invariably undergo primary pigment cell development (Cagan and Ready 1989), a possible explanation for this enhanced effect of lack of Spa protein in primary pigment cells might be that their development depends not only on their own Spa expression, but also on a signal whose secretion by cone cells also requires Spa function. Despite the severe effects on the differentiation of cone and primary pigment cells in spapol mutants, most cone cells and many primary pigment cells still can be recognized by their apical shapes and positions and are able to secrete the lenses. Therefore, although Spa is clearly required for proper development and differentiation of these cells, other factors exist that implement some characteristics of differentiating cone and primary pigment cells.

Although cone and primary pigment cells are the first, they are not the only ommatidial cells whose development is disturbed in the absence of Spa. The lack of proper development of cone and primary pigment cells and their disorganization in spapol mutants result in secondary effects that may prevent recruitment or development of secondary or even tertiary pigment cells, as the former are frequently missing between the primary pigment cells of adjacent ommatidia. A possible explanation might be that the Spitz signal, which recruits secondary pigment cells (Freeman 1996, 1997), is synthesized in primary pigment cells under Spa control.

Spa expression distinguishes cone cells from R7 cells in R7 equivalence group

According to the model proposed by Freeman (1996, 1997), cone cells are recruited by the Ras signaling pathway activated by the release from neighboring photoreceptor precursor cells of the epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like Spitz signal, which overcomes the inhibitory Argos signal. Cone cell precursors are also competent to become R7 cells in response to the Ras signaling pathway, when the pathway is activated prematurely by a constitutively active Sevenless (Sev) receptor at the time it is normally activated in wild-type R7 precursors (Basler et al. 1991; Dickson et al. 1992). Hence, cone cells constitute, together with R7, the R7 equivalence group (Greenwald and Rubin 1992). However, similar to R7 precursors lacking a functional Sev receptor (Tomlinson and Ready 1986), cone cells are not induced to develop toward an R7 cell fate because the Argos signal prevents them temporarily from receiving a Ras triggering signal (Freeman 1997). Because Spa is not expressed in R7 cells, its expression in newly recruited cone cells distinguishes their fate from that of R7 cells. The spa gene is thus a direct or indirect target of a transcription factor activated by selective phosphorylation through the Ras signaling pathway. Such a factor, whose synthesis would have to precede that of Spa, might be Lz, which is required in photoreceptors R1/R6, R7 as well as in cone cells (G. Shirley and U. Banerjee, pers. comm.) and which helps define the R7 equivalence group by repressing seven-up (svp) (Daga et al. 1996). Indeed, recent results are consistent with such a regulatory relationship between Lz and Spa (G. Shirley, W. Fu, U. Banerjee, and M. Noll, unpubl.).

Spa controls early Cut expression in cone cells and Bar expression in primary pigment cells

The observed eye phenotype of spapol mutants clearly shows that the Spa protein is required for the proper development and assembly of both cone and primary pigment cells rather than for their recruitment. The effects of loss of Spa function on the expression of the cut and Bar loci, which encode homeodomain-containing proteins expressed in cone cells (Dickson et al. 1995) and primary pigment cells (Higashijima et al. 1992a), respectively, further support this conclusion. Although initially Cut expression is reduced severely in cone cell precursors in the absence of Spa, these cells later express Cut and still resemble cone cells; their shape and cellular interactions, however, are much disturbed. In the absence of Lz, cone cell precursors derepress svp, fail to express Cut, and develop toward an outer photoreceptor fate (Daga et al. 1996). Hence, the recovery of Cut expression in spapol cone cells depends directly or indirectly on Lz, yet Lz does not affect Cut expression exclusively through Spa. Accordingly, in contrast to lz null mutants, cone cells do form in spapol mutants and retain some of their differentiative properties such as the ability to secrete corneal lenses, which, however, are frequently defective and fused or display the blueberry-eye phenotype (Basler et al. 1990).

After the accretion of all four cone cells to the developing ommatidia, primary pigment cells are recruited, presumably by the release of Spitz (Freeman 1997) from their neighboring anterior and posterior cone cells (Cagan and Ready 1989). As a result, Spa is again expressed in primary pigment cells where it is required for the activation of both cognate Bar genes. Our findings that Bar expression in primary pigment cells depends completely on Spa and that Spa also plays an indirect role in the recruitment or specification of secondary and of tertiary pigment cells is entirely consistent with the earlier observation that expression of Bar proteins in primary pigment cells is crucial for proper specification of all pigment cells (Higashijima et al. 1992a). The abundant fusion of lenses observed in spapol mutants, which has also been found in deficiency mutants of the Bar locus, might result from the improper development (Higashijima et al. 1992a) or lack of secondary pigment cells. Because neither Spa nor Bar are expressed in wild-type secondary and tertiary pigment cells, Spa might influence the fate of these cells by modulating the expression of the Spitz signal released from primary pigment cells (Freeman 1997).

spa is the Drosophila ortholog of the vertebrate Pax2 gene

As shown here, the spa gene belongs to the Pax2, Pax5, Pax8 subclass of the Pax gene family (Noll 1993; Stuart and Gruss 1995). Not only do these genes encode a highly conserved paired domain and octapeptide and a conserved order and structure of their remaining protein domains, but the locations of the introns within their paired domain and between their transactivation and inhibitory domain have also been conserved precisely (Kozmik et al. 1993; Sanyanusin et al. 1995; Busslinger et al. 1996; Dörfler and Busslinger 1996). In addition, their patterns of differential splicing and protein isoforms are very similar (Kozmik et al. 1993).

Because the three vertebrate genes Pax2, Pax5, Pax8 have arisen by duplications after the separation of deuterostomes from protostomes (Noll 1993), we cannot decide which of these three genes is most closely related to spa merely on a structural basis. However, in terms of its function, spa appears closest to the vertebrate Pax2 gene, as both genes are expressed in the developing eyes (Torres et al. 1996). This adds an additional gene to the list of conserved genes in eye development (Cvekl and Piatigorsky 1996) and supports the idea that eye development in different organisms is under the control of similar genetic cascades (Halder et al. 1995b), in agreement with the general hypothesis that gene networks have been conserved during evolution (Noll 1993). In particular, two Pax genes are now known to be conserved in vertebrate and insect eye development, Pax6 and its Drosophila homolog ey (Halder et al. 1995b) as well as Pax2 (Nornes et al. 1990; Püschel et al. 1992; Keller et al. 1994; Sanyanusin et al. 1995; Torres et al. 1996) and its homolog spa. Interestingly, both Pax genes control eye development in spatially distinct regions in vertebrates as well as in Drosophila. While Pax6 expression in the developing vertebrate eye is restricted to the optic vesicle, optic cup, and lens (Macdonald and Wilson 1996), Pax2 is expressed at the lips of the optic fissure and in the optic stalk epithelium, where its expression forms a sharp boundary to the pigmented retina of the optic cup expressing Pax6 (Torres et al. 1996). Similarly, ey is expressed anterior to the morphogenetic furrow in the undifferentiated part of the eye disc epithelium (Quiring et al. 1994), whereas spa expression in the precursors of cone and primary pigment cells lags well behind the furrow.

Human Pax2 heterozygotes suffer from bilateral optic nerve colobomas, indicating that Pax2 is crucially required for the closure of the optic fissure (Sanyanusin et al. 1995). Pax2 null mutant mice show a more severe eye phenotype. In addition to colobomas, they exhibit extension of the pigmented retina into the optic stalk and agenesis of the optic chiasma (Torres et al. 1996). Thus, it appears that, in the absence of Pax2, the optic stalk epithelium develops into pigmented retina and fails to proliferate and differentiate into glial cells, which populate the optic nerve and are essential for guidance of the retinal axons (Torres et al. 1996).

Assuming that the ancestral photosensory organ of proto- and deuterostomes already expressed Pax2, what might have been the role of such an ancestral Pax2 gene? Although we can only speculate about its role, it is interesting to note that both Pax2 and spa are expressed in accessory cells of neurons, in glial and cone cells. We might consider a cone cell as a kind of neuronal support, or glial, cell that evolved from a more primitive ancestral glial cell. In favor of such a hypothesis, we observed that spa is expressed in glial cells of the developing PNS (W. Boll, W. Fu, and M. Noll, unpubl.). In addition, we found that photoreceptor cells degenerate in spapol mutants, probably because of improperly differentiated cone cells, a situation that is reminiscent of the lack of proper axon guidance of the retinal ganglion cells in Pax2 null mutant mice (Torres et al. 1996). Accordingly, the electroretinogram is absent in spapol mutants (Grossfield 1975), while it is extremely abnormal in heterozygous Krd mice lacking one copy of Pax2 (Keller et al. 1994). Whatever the ancestral role of Pax2 might have been, both Pax2 and Pax6 and their Drosophila homologs spa and ey play important roles in the morphogenesis and regional specification of the vertebrate or insect eyes (Macdonald and Wilson 1996), and spa appears to be the ortholog of the vertebrate Pax2 gene.

Materials and methods

General procedures

Standard procedures, such as isolation and Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA, screening of genomic and cDNA libraries, isolation and subcloning of λ phage and plasmid DNAs, isolation and Northern analysis of poly(A)+ RNA, and in situ hybridization to salivary gland chromosomes were carried out essentially as described (Maniatis et al. 1982; Frei et al. 1985; Kilchherr et al. 1986). A cDNA expression library of poly(A)+ RNA from 4- to 8-hr-old embryos, constructed in the λ UNI-ZAP XR vector using the Stratagene ZAP cDNA synthesis kit (Schneitz et al. 1993), was immunoscreened with a 100-fold diluted rabbit anti-Poxm antiserum (Bopp et al. 1989) according to the protocol supplied by Stratagene. In this screen, one of the spa cDNA clones, cpx1, was isolated. Using cpx1 DNA as probe, additional spa cDNAs were isolated from cDNA libraries prepared from poly(A)+ RNAs of 4- to 8-hr and 8- to 12-hr-old embryos and of imaginal discs. Northern blot analysis showed several bands, mainly between 4.0 and 4.5 kb, in embryos and imaginal discs, probably reflecting the differential splicing and the various poly(A) addition sites used, and indicates that the longest cDNAs are close to full length. This is supported by the fact that six 5′ ends of 15 embryonic cDNAs are located within 10 nucleotides from the 5′ end of the longest cDNA shown in Figure 3A.

Three libraries were constructed in the λ DASH II vector (Stratagene) from homozygous spa1, spapol, and spap65 genomic DNA essentially as described (Frischauf et al. 1983). The spap65 mutation, analyzed in various stocks obtained from three stock centers, exhibited a deficiency identical to that of spapol. Because the spapol stock used was a direct descendant from the original mutant discovered by Hadorn (Rickenbacher 1954), we assume that the spap65 allele has been lost. Wild-type DNA clones of the spa locus were isolated from two genomic libraries, a KrSB1/CyO library prepared in EMBL4 (Baumgartner et al. 1987) and a Df(3R)der25/Df(3R)dcoEGX8 library prepared in λ DASH II by O. Zilian (this laboratory).

All DNA sequences were analyzed on both strands. The full-length cDNAs of spa were sequenced in the pSK− vector with a DNA sequencer model 373A using dye terminators (Applied Biosystems Inc.). All intron–exon boundaries were determined by Southern blot analysis of the genomic clones with cDNA probes and subsequent sequencing across the boundaries.

P-element-mediated rescue of spapol mutants

To rescue the spapol phenotype, a 926-bp SpeI enhancer fragment of spa intron 4 was cloned upstream of a nearly full-length spa cDNA, whose 5′ end had been extended by a spa promoter fragment of ∼330 bp and whose 3′ portion downstream of the EcoRV site of exon 9 had been replaced by the corresponding 5.1-kb genomic EcoRV–EcoRI fragment (Fig. 3A), into the P-element vector PW6 carrying the mini-white gene as marker (Klemenz et al. 1987). Several transgenic stocks carrying a single copy of this spa transgene, such as w; P[w+; spa+]/TM3, Sb; spapol/spapol, showed complete rescue of the spapol phenotype, i.e., the eye phenotype of all adults was indistinguishable from that of wild-type flies (cf. Fig. 5A).

In situ hybridization to whole-mount embryos and imaginal discs

In situ hybridization to embryos and imaginal discs (including the brain and ventral ganglion) with DIG-labeled cpx1 DNA was carried out essentially as described (Tautz and Pfeifle 1989; Schneitz et al. 1993) except that a single-stranded probe was prepared and detected, using a DIG DNA-labeling and detection kit and following the included protocol (Boehringer).

Scanning electron microscopy and histology

Scanning electron microscopy, carried out by Urs Jauch (Institut für Pflanzenbiologie, Zürich, Switzerland), and histological sections of adult eyes were performed as described by Basler et al. (1991). Cobalt sulfide staining of pupal discs was carried out essentially according to Cagan and Ready (1989).

Immunohistochemistry

Rabbit anti-Spa antiserum was generated and purified essentially as described (Gutjahr et al. 1993) except that a spa cDNA fragment encoding a 205-amino-acid peptide (amino acids 308–512 in Fig. 3B) was cloned between the BamHI and EcoRI site of the pGEX–3X GST fusion vector (Pharmacia), expressed, and used for immunization of rabbits. Embryos were immunostained for Spa protein as described (Gutjahr et al. 1993) except that mounting occurred in 85% glycerol, whereas stainings of imaginal discs were performed according to Gaul et al. (1992). The specificity of the anti-Spa antiserum was ascertained by its staining patterns in embryos and eye discs that were identical to those obtained by in situ hybridizations with a DIG-labeled cpx1 probe and that were eliminated in homozygous Df(4)G embryos.

Acknowledgments

Our special thanks goes to E. Hafen, M. Domínguez, and A. van der Straten for their expert advice and generous help, and our colleagues in the laboratory for stimulating discussions and support. We thank J. Alcedo, E. Hafen, K. Basler, B. Dickson, and H. Noll for critical comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to U. Jauch at the Institut für Pflanzenbiologie for the scanning electron microscopy, P. Spielmann for DNA sequencing, and F. Ochsenbein for the artwork. We thank K. Blochlinger for anti-Cut and K. Saigo for anti-Bar antiserum, the Drosophila stock centers at Bloomington, Bowling Green, and Umea for spa mutant stocks, A. Carpenter for the spaA stock, and R. Nöthiger for the original spapol stock. This work has been supported by Swiss National Science Foundation grants 31-26652.89 and 31-40874.94 (to M.N.) and by the Kanton Zürich.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Note added in proof

The GenBank accession number for the longest spa cDNA reported in this article is AF010256.

Footnotes

E-MAIL noll@molbio2.unizh.ch; FAX 011-41-1-635-6811.

References

- Basler K, Yen D, Tomlinson A, Hafen E. Reprogramming cell fate in the developing Drosophila retina: Transformation of R7 cells by ectopic expression of rough. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:728–739. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.5.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler K, Christen B, Hafen E. Ligand-independent activation of the sevenless receptor tyrosine kinase changes the fate of cells in the developing Drosophila eye. Cell. 1991;64:1069–1081. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90262-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner S, Bopp D, Burri M, Noll M. Structure of two genes at the gooseberry locus related to the paired gene and their spatial expression during Drosophila embryogenesis. Genes & Dev. 1987;1:1247–1267. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.10.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blochlinger K, Jan LY, Jan YN. Postembryonic patterns of expression of cut, a locus regulating sensory organ identity in Drosophila. Development. 1993;117:441–450. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp D, Jamet E, Baumgartner S, Burri M, Noll M. Isolation of two tissue-specific Drosophila paired box genes, pox meso and pox neuro. EMBO J. 1989;8:3447–3457. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busslinger M, Klix N, Pfeffer P, Graninger PG, Kozmik Z. Deregulation of PAX-5 by translocation of the Eμ enhancer of the IgH locus adjacent to two alternative PAX-5 promoters in a diffuse large-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:6129–6134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagan RL, Ready DF. The emergence of order in the Drosophila pupal retina. Dev Biol. 1989;136:346–362. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavener DR. Comparison of the consensus sequence flanking translational start sites in Drosophila and vertebrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:1353–1361. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.4.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvekl A, Piatigorsky J. Lens development and crystallin gene expression: Many roles for Pax-6. BioEssays. 1996;18:621–630. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daga A, Karlovich CA, Dumstrei K, Banerjee U. Patterning of cells in the Drosophila eye by Lozenge, which shares homologous domains with AML1. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1194–1205. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson B. Nuclear factors in sevenless signalling. Trends Genet. 1995;11:106–111. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)89011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson B, Hafen E. Genetic dissection of eye development in Drosophila. In: Bate M, Martinez Arias A, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 1327–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson B, Sprenger F, Hafen E. Prepattern in the developing Drosophila eye revealed by an activated torso-sevenless chimeric receptor. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:2327–2339. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson BJ, Domínguez M, van der Straten A, Hafen E. Control of Drosophila photoreceptor cell fates by Phyllopod, a novel nuclear protein acting downstream of the Raf kinase. Cell. 1995;80:453–462. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90496-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörfler P, Busslinger M. C-terminal activating and inhibitory domains determine the transactivation potential of BSAP (Pax-5), Pax-2 and Pax-8. EMBO J. 1996;15:1971–1982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M. Reiterative use of the EGF receptor triggers differentiation of all cell types in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 1996;87:651–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Cell determination strategies in the Drosophila eye. Development. 1997;124:261–270. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei E, Baumgartner S, Edström J-E, Noll M. Cloning of the extra sex combs gene of Drosophila and its identification by P-element-mediated gene transfer. EMBO J. 1985;4:979–987. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischauf A-M, Lehrach H, Poustka A, Murray N. Lambda replacement vector carrying polylinker sequences. J Mol Biol. 1983;170:827–842. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaul U, Mardon G, Rubin GM. A putative Ras GTPase activating protein acts as a negative regulator of signaling by the Sevenless receptor tyrosine kinase. Cell. 1992;68:1007–1019. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90073-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald I, Rubin GM. Making a difference: The role of cell–cell interactions in establishing separate identities for equivalent cells. Cell. 1992;68:271–281. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90470-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossfield J. Bahavioral mutants of Drosophila. In: King RC, editor. Handbook of genetics. New York, NY: Plenum; 1975. pp. 679–702. [Google Scholar]

- Gutjahr T, Frei E, Noll M. Complex regulation of early paired expression: Initial activation by gap genes and pattern modulation by pair-rule genes. Development. 1993;117:609–623. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G, Callaerts P, Gehring WJ. Induction of ectopic eyes by targeted expression of the eyeless gene in Drosophila. Science. 1995a;267:1788–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.7892602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— New perspectives on eye evolution. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995b;5:602–609. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashijima S, Kojima T, Michiue T, Ishimaru S, Emori Y, Saigo K. Dual Bar homeo box genes of Drosophila required in two photoreceptor cells, R1 and R6, and primary pigment cells for normal eye development. Genes & Dev. 1992a;6:50–60. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashijima S, Michiue T, Emori Y, Saigo K. Subtype determination of Drosophila embryonic external sensory organs by redundant homeo box genes BarH1 and BarH2. Genes & Dev. 1992b;6:1005–1018. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochman B. Analysis of chromosome 4 in Drosophila melanogaster. II: Ethyl methanesulfonate induced lethals. Genetics. 1971;67:235–252. doi: 10.1093/genetics/67.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SA, Jones JM, Boyle A, Barrow LL, Killen PD, Green DG, Kapousta NV, Hitchcock PF, Swank RT, Meisler MH. Kidney and retinal defects (Krd), a transgene-induced mutation with a deletion of mouse chromosome 19 that includes the Pax2 locus. Genomics. 1994;23:309–320. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilchherr F, Baumgartner S, Bopp D, Frei E, Noll M. Isolation of the paired gene of Drosophila and its spatial expression during early embryogenesis. Nature. 1986;321:493–499. [Google Scholar]

- Klemenz R, Weber U, Gehring WJ. The white gene as a marker in a new P-element vector for gene transfer in Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3947–3959. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.10.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozmik Z, Kurzbauer R, Dörfler P, Busslinger M. Alternative splicing of Pax-8 gene transcripts is developmentally regulated and generates isoforms with different transactivation properties. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6024–6035. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss S, Johnson T, Korzh V, Fjose A. Expression of the zebrafish paired box gene Pax[zf-b] during early neurogenesis. Development. 1991;113:1193–1206. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley DL, Zimm GG. The genome of Drosophila melanogaster. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald R, Wilson SW. Pax proteins and eye development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:49–56. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan LV. A variable phenotype associated with the fourth chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster and affected by heterochromatin. Genetics. 1947;32:200–219. doi: 10.1093/genetics/32.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll M. Evolution and role of Pax genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:595–605. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nornes HO, Dressler GR, Knapik EW, Deutsch U, Gruss P. Spatially and temporally restricted expression of Pax-2 during murine neurogenesis. Development. 1990;109:797–809. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster II, Crang RE. Scanning electron microscopy of Drosophila mutant and wild type eyes. Trans Amer Micros Soc. 1972;91:600–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Püschel AW, Westerfield M, Dressler GR. Comparative analysis of Pax-2 protein distributions during neurulation in mice and zebrafish. Mech Dev. 1992;38:197–208. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(92)90053-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiring R, Walldorf U, Kloter U, Gehring WJ. Homology of the eyeless gene of Drosophila to the Small eye gene in mice and Aniridia in humans. Science. 1994;265:785–789. doi: 10.1126/science.7914031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickenbacher J. Poliert (pol), eine neue Augenmutante im 4. Chromosom bei Drosophila melanogaster Meig. Z indukt Abstamm Vererbungsl. 1954;86:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyanusin P, Schimmenti LA, McNoe LA, Ward TA, Pierpont ME, Sullivian MJ, Dobyns WB, Eccles MR. Mutation of the PAX2 gene in a family with optic nerve colobomas, renal anomalies and vesicoureteral reflux. Nature Genet. 1995;9:358–364. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneitz K, Spielmann P, Noll M. Molecular genetics of aristaless, a prd-type homeo box gene involved in the morphogenesis of proximal and distal pattern elements in a subset of appendages in Drosophila. Genes & Dev. 1993;7:114–129. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart ET, Gruss P. PAX genes: What’s new in developmental biology and cancer? Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1717–1720. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.suppl_1.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumm-Tegethoff BFA, Dicke AW. Surface structure of the compound eye of various Drosophila species and eye mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Theoret Appl Genet. 1974;44:262–265. doi: 10.1007/BF00278740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D, Pfeifle C. A nonradioactive in situ hybridization method for the localization of specific RNAs in Drosophila embryos reveals translational control of the segmentation gene hunchback. Chromosoma. 1989;98:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00291041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson A, Ready DF. Sevenless: A cell-specific homeotic mutation of the Drosophila eye. Science. 1986;231:400–402. doi: 10.1126/science.231.4736.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres M, Gómez-Pardo E, Gruss P. Pax2 contributes to inner ear patterning and optic nerve trajectory. Development. 1996;122:3381–3391. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff T, Ready DF. Pattern formation in the Drosophila retina. In: Bate M, Martinez Arias A, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 1277–1325. [Google Scholar]

- Zipursky SL, Rubin GM. Determination of neuronal cell fate: Lessons from the R7 neuron of Drosophila. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:373–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]