Abstract

Objective

Social phobia typically develops during the adolescent years, yet no nationally representative studies in the United States have examined the rates and features of this condition among youth in this age range. The objectives of this investigation are to: (1) present the lifetime prevalence, sociodemographic and clinical correlates, and comorbidity of social phobia in a large, nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents; (2) examine differences in the rates and features of social phobia across the proposed DSM-5 social phobia subtypes.

Method

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) is a nationally representative face-to-face survey of 10,123 adolescents aged 13–18 years in the continental U.S.

Results

Approximately 9% of adolescents met criteria for any social phobia in their lifetime. Of these adolescents, 55.8% were affected with the generalized subtype and 44.2% exhibited non-generalized social phobia. Only 0.7% met criteria for the proposed DSM-5 performance only subtype. Generalized social phobia was more common among female adolescents and risk for this subtype increased with age. Adolescents with generalized social phobia also experienced an earlier age of onset, higher levels of disability and clinical severity, and a greater degree of comorbidity relative to adolescents with non-generalized forms of the disorder.

Conclusions

This study indicates that social phobia is a highly prevalent, persistent, and impairing psychiatric disorder among adolescent youth. Results of this study also provide evidence for the clinical utility of the generalized subtype and highlight the importance of considering the heterogeneity of social phobia in this age group.

Keywords: Epidemiology, adolescents, social phobia, subtypes, National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement

Presenting primarily during late childhood or adolescence,1–3 social phobia is a highly persistent and impairing condition.3–5 Although there are numerous community and nationally representative studies of social phobia among adults,3,5 comparatively few general population studies of social phobia exist among youth. Moreover, current information on social phobia in youth is largely derived from studies conducted outside of the United States.4,6–11 To date, no nationally representative studies conducted in the U.S. have examined the prevalence and features of social phobia among adolescents.

Among the small number of studies that have examined social phobia in community samples of youth, available data have uniformly indicated that affected individuals exhibit a high degree of impairment and associated comorbidity.4,6,7 However, results concerning the prevalence, sociodemographic correlates, and course of social phobia have varied substantially across studies. Indeed, lifetime prevalence estimates of social phobia range between 1.4% and 7.3% across recent community surveys.1 Results of studies have similarly differed with regard to the effects of sociodemographic characteristics, with some studies finding social phobia to predominate among female and older aged youth,4,12,13 and others finding no significant effects of gender7,8 or age9 on rates of the disorder. Likewise, whereas some studies have found youth with social phobia to display a persistent course,14,15 others have found a highly variable and remitting course among youth.16,17

Although inconsistent results across studies may be due to dissimilar sampling strategies and diagnostic instruments, such discrepancies may also reflect changes in diagnostic criteria over time18 and/or variations in the clinical presentation of social phobia. Toward this end, few general population studies of youth have applied current diagnostic criteria for social phobia, 4,6,7,9 and fewer still have examined rates and features of the generalized subtype of the disorder.4,10 As well, recent proposals to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) include an additional performance only subtype of social phobia that may be designated when the social fear “is restricted to speaking or performing in public”.19 However, only one previous study has examined the prevalence and characteristics of this subtype in youth.11 In consideration of the shortage of studies that have examined current and proposed social phobia subtypes in young people, an examination of the appropriateness and utility of these subtypes in youth is of particular significance. Further, because social phobia typically develops during the adolescent years,1,2 investigations of this condition at the height of initial onset provide a unique opportunity to understand its early expression and features.3,7

Accordingly, the current study aims to: (1) present the prevalence, sociodemographic and clinical correlates, and comorbidity of social phobia in a large, nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents; and (2) examine differences in these parameters across proposed DSM-5 subtypes of social phobia.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) is a nationally representative face-to-face survey of 10,123 adolescents ages 13–18 years in the continental U.S.20 Information concerning the sampling strategy, participation rates, and instruments in the NCS-A can be found in greater detail elsewhere.21,22 The survey was carried out in a dual-frame sample that included a household subsample (n = 879) and a school subsample (n = 9244).21 The adolescent response rate of the combined sub-samples was 82.9%. Minor differences in sample and population distributions of census sociodemographic and school characteristics were corrected with post-stratification weighting.21

One biological parent/parent surrogate of each participating adolescent was mailed a self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) to collect information on adolescent mental and physical health, and other family- and community-level factors. In families where the full SAQ could not be obtained, parents were invited to complete an abbreviated SAQ via in-person or telephone interviews.21 The full SAQ was completed by 6,483 parents and the abbreviated SAQ was completed by 1,994 parents, yielding an overall conditional response rate of 83.3% (biological parents: 90.8%; parent surrogates: 9.2%) among participating adolescents. All recruitment and consent procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan.

Measures

Sociodemographic Variables

Socio-demographic variables assessed in the NCS-A that were used in the present study include age (in years), sex, race/ethnicity, and the poverty index ratio (PIR). The PIR is based on family size and the ratio of family income to the family's poverty threshold level (<=1.5 poor, <=3, <=6, and >6).

Diagnostic Assessment

Adolescents were administered a modified version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI), a fully structured interview of DSM-IV diagnoses.23 Lifetime disorders assessed by the CIDI include social phobia as well as other anxiety disorders (separation anxiety disorder [SAD], specific phobia, agoraphobia, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder [GAD]), mood disorders (major depressive disorder [MDD], dysthymic disorder), behavior disorders (oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], conduct disorder [CD], attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]), alcohol use disorders (alcohol abuse/dependence) and drug use disorders (drug abuse/dependence). Psychiatric disorders derived from the modified CIDI showed good concordance with a clinical reappraisal subsample.24 Parents who completed the full SAQ provided diagnostic information about three emotional (MDD, dysthymia, SAD) and three behavioral (ODD, CD, ADHD) disorders, whereas those completing the abbreviated SAQ only reported on ADHD. Because prior research indicates that adolescents may be the most accurate informants concerning their emotional symptoms,25 only adolescent reports were used to assess diagnostic criteria for emotional disorders. By contrast, information from both the parent and adolescent were combined and classified as positive if either informant endorsed the diagnostic criteria for ODD and CD, and only parent reports were employed for diagnoses of ADHD.25,26 For those disorders for which parent reports were used, estimation of DSM-IV disorders were based on the full SAQ. Definitions of all psychiatric disorders adhered to DSM-IV criteria and all diagnostic hierarchy rules were applied.

Social Phobia and Subtype Definitions

Twelve social fears representing interactional, observational, and performance situations were assessed among adolescents: meeting new people your own age; talking to people in authority, like teachers, coaches, or other adults you don’t know very well; being with a group of people your own age, like at a party or in the lunchroom at school; going into a room that already has people in it; talking with people you don’t know very well; going out with/dating someone you are interested in; any other situation where you could be the center of attention/where something embarrassing might happen; working/doing homework while someone watches; writing/eating/drinking while someone watches; speaking in class when a teacher asks a question/when a teacher calls on you; acting/performing/giving a talk in front of a group of people; taking an important test/exam or interviewing for a job, even though you were well prepared.

Adolescents met DSM-IV lifetime criteria for social phobia if they endorsed marked and persistent fear in at least one of the 12 social situations assessed and fulfilled all other developmentally-appropriate criteria: (1) exposure to the situation almost invariably provokes anxiety; (2) the situation is avoided or endured with intense anxiety/distress; (3) having the fear causes marked distress or significant interference in functioning; and (4) the fear persists for at least 6 months.27 Past year cases of social phobia included adolescents who endorsed having the social fear(s) to an extensive or impairing degree in the past 12 months prior to the interview. Consistent with DSM-IV/DSM-5 definitions, cases of generalized social phobia included all adolescents with lifetime social phobia who endorsed a majority of the 12 social fears assessed (i.e., ≥ 7). A residual category of non-generalized social phobia included the remaining adolescents with lifetime social phobia who failed to endorse a majority of social fears (i.e., < 7). Further, in adherence with the DSM-5 definition of performance only social phobia, cases of this subtype included adolescents with lifetime social phobia who exclusively endorsed a fear of “acting, performing, or giving a talk in front of a group of people.”

Clinical Features

Severe Cases

Distress and impairment criteria for DSM-IV social phobia of any severity required adolescents to endorse “moderate,” “severe,” or “very severe” levels of distress or “some,” “a lot,” or “extreme” levels of impairment. However, similar to our previous work,22 severe lifetime cases of social phobia were defined by higher thresholds that required endorsement of “severe” or “very severe” distress in conjunction with “a lot” or “extreme” impairment in daily activities.

Past Year Impairment and Days Out of Role

Adolescents with any past year social fear were asked to rate the degree of impairment and disability they experienced during the worst month of the previous year in the areas of household chores, school or work, family relations, and social life (Sheehan Disability Scale).28 The response scale ranged from 0–10 and included verbal anchors of “none” (0), “mild” (1–3), “moderate” (4–6), “severe” (7–9), and “very severe” (10). The maximum value endorsed by respondents across the four areas was used as an indication of past year impairment. An additional item required respondents to estimate the total number of days in the previous year that they were totally unable to carry out their normal activities because of their social fear.

Age of Onset and Duration

Age-of-onset (AOO) information was obtained from adolescents using an assessment procedure created to enhance retrospective recall. Adolescents were asked whether they could remember their “exact age the very first time” they experienced symptoms of the disorder. Adolescents who could not recall their exact age were further probed by progressing up the age range in a step-wise fashion using developmental milestones as steps (e.g., “Can you remember what grade you were in at school?”; “Was it before you were a teenager?”). Experimental research has demonstrated that the emphasis on recall of an exact age coupled with step-wise probing significantly improves the accuracy of AOO data.29 Age-of-offset data were assessed by asking adolescents to report their age “the last time they either strongly feared or stayed away from the social situation(s).” The duration of social phobia was calculated as the difference between age-of-offset and age-of-onset of the disorder. When adolescents reported no age-of-offset, duration was calculated as the difference between age-of-onset and the current age of the adolescent.

Lifetime Treatment Contact for Social Phobia or Other Anxiety Disorders

Adolescents were asked whether they had ever discussed their social fear with a professional (e.g., “Did you ever in your life talk to a medical doctor or other professional about your fear of [this/these situation(s)]?”). Types of professionals included psychologists, counselors, spiritual advisors, herbalists, acupuncturists, and other healing professionals. A dichotomous index of lifetime social phobia treatment contact was generated by positively scoring cases who endorsed seeking treatment for social phobia at some point in their lifetime. Information from all other anxiety disorder sections was aggregated to create a parallel variable of lifetime treatment contact for other anxiety disorders.

Any Lifetime Services

In a separate section of the CIDI, adolescents were asked whether they had received services for any emotional or behavioral problems in their lifetime. Types of services assessed included mental health specialty, general medical, human services, complimentary alternative medicine, or school services. Information about the types of services assessed are described in detail elsewhere.30

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were completed in the SUDAAN software package31 using the Taylor series linearization method to take into account the complex survey design. The Taylor series linearization method is a common technique used to estimate the covariance matrix of regression coefficients for complex survey data.32 We used the Taylor series design-based coefficient variance-covariance matrices for variance estimates and multivariate significant tests. Cross-tabulations were used to calculate estimates of the prevalence, clinical features, and comorbidity. Means were used for continuous clinical characteristics. The age-specific incidence curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to examine demographic correlates of the prevalence of social phobia and its subtypes; regression models included all sociodemographic variables and other psychiatric disorders simultaneously. Adjusted odds ratios were the exponentiated values of multivariate logistic regression coefficients. Confidence intervals (95%) of adjusted odds ratios were calculated based on design-adjusted variances. The design-adjusted Wald chi-square test (for categorical variables) or Wald F test (for continuous variables) was used to examine differences across subtypes and statistical significance was based on two-sided tests evaluated at the 0.05 level of significance.

Results

Prevalence and Correlates

The lifetime prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of social phobia are presented overall and by subtype in Table 1. As is shown, 8.6% of adolescents met criteria for any social phobia in their lifetime. Prevalence rates by subtype indicated that 4.8% of adolescents met criteria for the generalized subtype, corresponding to 55.8% of all adolescents with social phobia. By contrast, 3.8% of adolescents did not meet criteria for the generalized subtype (displayed as non-generalized), equaling 44.2% of all adolescents with social phobia. Approximately 0.7% of adolescents fulfilled criteria for the DSM-5 performance only subtype, representing only 0.8% of all adolescents with social phobia (results not shown, but available upon request). Because of its extremely low prevalence and the likelihood of unstable estimates, further examination of the performance only subtype was prohibitive. For this reason, only generalized and non-generalized social phobia were examined in remaining analyses.

Table 1.

Prevalence Estimates and Demographic Correlates of Lifetime Social Phobia and Subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (N=10,123)

|

Correlates |

n |

Any Social Phobia | Non-Generalized | Generalized | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (SE) | aOR (95% CI) | % (SE) | aOR (95% CI) | % (SE) | aOR (95% CI) | |||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 5,170 | 9.2 (0.7) | 1.17 (0.97–1.42) | 3.4 (0.4) | 0.80 (0.54–1.18) | 5.9 (0.6) | 1.58 (1.18–2.12) | |

| Male | 4,953 | 7.9 (0.6) | 1.00 | 4.1 (0.5) | 1.00 | 3.8 (0.4) | 1.00 | |

| χ2(1) | 2.7 | 1.3 | 9.8** | |||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 13–14 | 3,870 | 6.3 (0.7) | 1.00 | 2.9 (0.4) | 1.00 | 3.3 (0.5) | 1.00 | |

| 15–16 | 3,897 | 9.6 (0.9) | 1.56 (1.23–1.98) | 4.3 (0.6) | 1.47 (1.06–2.02) | 5.3 (0.7) | 1.60 (1.06–2.40) | |

| 17–18 | 2,356 | 10.4 (1.0) | 1.71 (1.22–2.40) | 4.1 (0.7) | 1.38 (0.84–2.29) | 6.3 (0.8) | 1.94 (1.30–2.91) | |

| χ2(2) | 20.3*** | 6.0 | 11.5** | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanics | 1,914 | 8.3 (1.5) | 1.02 (0.64–1.61) | 2.5 (0.4) | 0.66 (0.40–1.07) | 5.8 (1.2) | 1.35 (0.79–2.32) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1,953 | 8.3 (1.5) | 1.03 (0.63–1.66) | 3.3 (1.0) | 0.89 (0.42–1.91) | 5.0 (0.9) | 1.15 (0.73–1.81) | |

| Other | 622 | 10.0 (1.5) | 1.25 (0.87–1.80) | 4.0 (0.9) | 1.04 (0.63–1.74) | 6.0 (1.2) | 1.43 (0.91–2.24) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 5,634 | 8.6 (0.6) | 1.00 | 4.1 (0.5) | 1.00 | 4.4 (0.5) | 1.00 | |

| χ2(3) | 1.6 | 6.0 | 3.7 | |||||

| Poverty Index Ratio | ||||||||

| <=1.5 Poor | 1,717 | 8.3 (0.9) | 0.89 (0.62–1.29) | 2.7 (0.5) | 0.67 (0.41–1.08) | 5.7 (0.8) | 1.07 (0.65–1.76) | |

| <=3.0 | 2,023 | 6.9 (0.8) | 0.73 (0.51–1.02) | 3.0 (0.5) | 0.73 (0.46–1.15) | 3.9 (0.6) | 0.75 (0.48–1.16) | |

| <=6.0 | 3,101 | 8.6 (0.7) | 0.90 (0.69–1.18) | 4.1 (0.4) | 0.98 (0.70–1.38) | 4.4 (0.5) | 0.85 (0.60–1.20) | |

| > 6.0 | 3,282 | 9.6 (0.9) | 1.00 | 4.3 (0.6) | 1.00 | 5.2 (0.7) | 1.00 | |

| χ2(3) | 4.9 | 4.3 | 3.5 | |||||

| Total | 10,123 | 8.6 [0.5) | 3.8 (0.3) | 4.8 (0.4) | ||||

Note: P values are based on Wald chi-square tests. aOR=Models adjusted for adolescent sex, age, race/ethnicity, and poverty index ratio. CI = confidence interval.

p ≤ 0. 01;

p ≤ 0.001

With regard to sociodemographic correlates, the prevalence of any social phobia was significantly associated with age, such that the disorder was 1.7 times more likely to occur in the oldest age group relative to the youngest age group. However, analysis by subtype indicated that the effect of age was present only among adolescents with generalized social phobia, with the oldest adolescents experiencing nearly a 2-fold increased risk of this subtype. Although gender was not associated with the presence of any social phobia, females were more likely to experience generalized social phobia relative to males. Neither race/ethnicity nor poverty was associated with social phobia in any form.

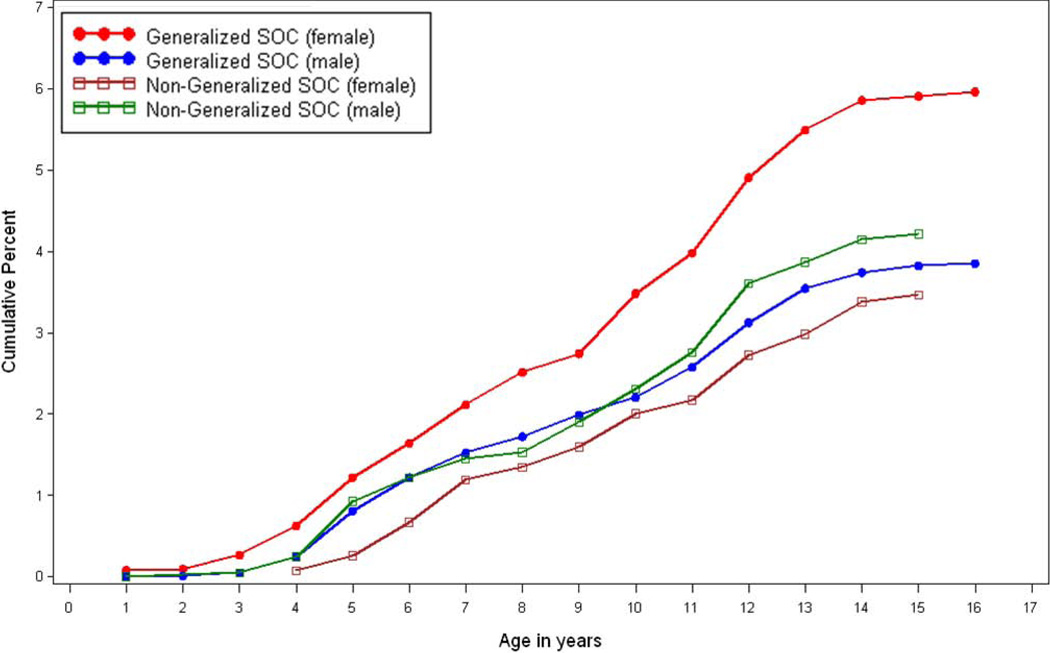

The age-specific incidence curves for lifetime social phobia are displayed by subtype and adolescent sex in Figure 1. The median age of onset of any social phobia was 9.2 years (age-specific incidence curve available upon request). The log-rank test for differences in survival functions indicated that the generalized and non-generalized social phobia curves were significantly different in the overall sample (Wald χ2(1)=2166.5, p<.0001); adolescents with generalized social phobia had an earlier age of onset than did adolescents with non-generalized social phobia (Mdn = 8.7 vs. 9.4 years). While there were no sex differences in the age of onset of non-generalized social phobia, multivariate analyses controlling for age and other psychiatric disorders indicated that males with generalized social phobia demonstrated a significantly earlier age of onset relative to females with generalized social phobia (Wald F(1)=5.0, p=.032). However, examination of the two-way interaction between social phobia subtype and adolescent sex was not significant.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Lifetime Prevalence of Social Phobia Subtypes by Adolescent Sex. Note: SOC = social phobia.

Clinical Features

Clinical features among unaffected adolescents with any social fear and those adolescents with any lifetime social phobia are presented overall and by subtype in Table 2. Demonstrating the clinical significance of the disorder, unaffected adolescents with any social fear uniformly displayed lower ratings across a number of clinical measures relative to adolescents who met criteria for the disorder. On average, adolescents with any social phobia reported a degree of disability in the moderate range (M=5.92), endorsed approximately seven social fears, and reported being totally unable to function for four days out of the last calendar year. After excluding cases of social phobia with onset in the past year, the prevalence ratio (past year of lifetime) indicated that social phobia was highly persistent in these youth; past year social phobia was present in 87.03% of adolescents who had experienced the disorder in their lifetime. As is displayed, adolescents with generalized social phobia experienced a higher degree of clinical severity than did adolescents with non-generalized social phobia on a variety of clinical measures. These adolescents endorsed higher levels of disability (M=6.28 vs. M=5.37, p<0.01) and experienced their disorder for a longer duration (M=6.29 years vs. M=5.61 years, p<0.01) than did those with non-generalized social phobia. In addition, a higher proportion of adolescents with generalized vs. non-generalized social phobia were defined as severe cases (25.31% vs. 9.79%, p<0.001) and had contacted a professional concerning their social fears (12.59%, vs. 3.42%, p<0.01). Despite differences in the rate of treatment contact across subtypes, these values were systematically low for all forms of social phobia. Only 8.55% of adolescents with social phobia (12.59% with generalized and 3.42% with non-generalized social phobia) had ever contacted a professional about social fears in their lifetime.

Table 2.

Clinical Correlates of Any Social Fear and Lifetime Social Phobia and Subtypes

|

Clinical features |

Any Social Feara |

Any Social Phobia |

Non-generalized | Generalized | Generalized vs. Non-generalized |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | F(1) | |

| Sheehan Disability Scaleb | 1.83 (0.28) | 5.92 (0.18) | 5.37 (0.25) | 6.28 (0.24) | 10.2** |

| Number of Fearsb | 1.96 (0.08) | 6.96 (0.16) | 4.53 (0.12) | 8.88 (0.13) | 518.1*** |

| Days Out of Roleb | 0.09 (0.08) | 4.24 (1.03) | 2.04 (0.94) | 5.62 (1.65) | 1.1 |

| Duration (in years)b | n/a | 5.99 (0.20) | 5.61 (0.30) | 6.29 (0.21) | 6.6** |

| % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | χ2(1) | |

| Severe Casesb | n/a | 18.47 (1.85) | 9.79 (1.84) | 25.31 (2.59) | 11.5*** |

| Prevalence Ratio (Past Year of Lifetime)b,c | n/a | 87.03 (2.13) | 84.19 (3.15) | 89.27 (2.35) | 1.7 |

| Social Phobia Treatment Contactb | 1.45 (0.21) | 8.55 (1.40) | 3.42 (1.66) | 12.59 (1.93) | 7.0** |

| Anxiety Treatment Contactb | 3.07 (0.25) | 18.46 (2.18) | 11.77 (2.98) | 23.72 (2.81) | 3.2 |

| Treatment for Any Problemd | 44.74 (1.05) | 60.78 (3.18) | 57.80 (5.47) | 63.20 (4.38) | 0.0 |

Note: Models adjusted for adolescent sex, age, and comorbid anxiety, emotional, and behavioral disorders; Impairment ratings were limited to those adolescents who endorsed any fear within the previous 12 months (n = 952). P values based on Wald chi-square or Wald F test. n/a=not applicable; SE = standard error.

Excluding cases who met criteria for social phobia.

Reports based on adolescent Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; n=10,123).

Cases of social phobia with onset in the past year were excluded from prevalence ratio estimations.

Reports based on adolescent CIDI and parent self-administered questionnaire sample (n=6,483);

p ≤ 0. 01;

p ≤ 0.001;

Psychiatric Comorbidity

The lifetime comorbidity of social phobia with other psychiatric disorders is presented for any social phobia and by subtype in Table 3. Initial univariate models indicated that social phobia was associated with all other psychiatric disorders (results not shown, but available upon request). However, after adjusting for other anxiety, mood, and behavior disorders in multivariate models, social phobia displayed significant associations only with several specific psychiatric disorders. Social phobia was most frequently associated with other anxiety disorders, with approximately one-third to one-fifth of these adolescents also affected with an additional anxiety disorder in their lifetime. Lifetime ODD and drug use disorders were also more common among adolescents with social phobia, representing 17.8% (SE=4.0%) and 20.1% (SE=2.5%) of these adolescents, respectively. Although 18.6% (SE = 1.6%) of adolescents with social phobia also presented with a lifetime mood disorder, adjusted odds ratios indicated that these associations were primarily due to other anxiety or behavior disorders.

Table 3.

Association of Lifetime Social Phobia and Subtypes With Other Mental Disorders

|

Disorder |

Any Social Phobia | Non-generalized | Generalized | Generalized vs. Non-generalized χ2(1) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (SE) | aOR (95% CI) | % (SE) | aOR (95% CI) | % (SE) | aOR (95% CI) | ||

| Anxiety Disordersa | 20.1 (1.5) | 3.46 (2.64–4.55) | 7.3 (0.8) | 3.33 (2.22–5.00) | 12.8 (1.3) | 3.17 (1.96–5.11) | 28.7*** |

| Specific Phobia | 21.5 (1.6) | 2.33 (1.66–3.26) | 8.5 (0.9) | 2.59 (1.60–4.21) | 13.0 (1.4) | 1.91 (1.23–2.97) | 7.8** |

| Agoraphobia | 32.4 (6.2) | 4.00 (2.28–7.02) | 5.5 (2.0) | 1.26 (0.48–3.32) | 27.0 (6.2) | 5.32 (3.24–8.74) | 43.5*** |

| Panic Disorder | 27.2 (4.7) | 2.01 (0.99–4.07) | 6.7 (3.0) | 1.35 (0.37–4.88) | 20.5 (4.1) | 2.26 (1.21–4.22) | 8.0** |

| PTSD | 24.4 (3.9) | 1.38 (0.7–2.61) | 7.3 (1.5) | 2.03 (1.10–3.76) | 17.1 (3.5) | 1.00 (0.46–2.17) | 0.0 |

| GAD | 32.0 (7.0) | 1.84 (0.68–5.03) | 7.7 (3.2) | 1.17 (0.29–4.71) | 24.4 (7.6) | 2.05 (0.61–6.91) | 1.4 |

| SAD | 27.4 (3.2) | 3.19 (2.07–4.91) | 9.3 (1.9) | 2.25 (1.00–5.06) | 18.1 (3.1) | 3.29 (1.96–5.54) | 16.1*** |

| Mood Disordersa | 18.6 (1.6) | 1.48 (0.80–2.74) | 5.3 (0.8) | 1.08 (0.53–2.19) | 13.3 (1.6) | 1.64 (0.79–3.41) | 2.4 |

| Major Depression | 18.7 (1.6) | 1.67 (0.89–3.14) | 5.4 (0.8) | 1.27 (0.60–2.67) | 13.3 (1.6) | 1.81 (0.85–3.83) | 3.1 |

| Dysthymia | 17.4 (3.5) | 0.42 (0.16–1.06) | 3.2 (1.1) | 0.25 (0.04–1.36) | 14.2 (3.3) | 0.51 (0.18–1.45) | 0.3 |

| Behavior Disordersb | 15.2 (2.1) | 1.93 (1.14–3.28) | 5.5 (1.1) | 1.96 (0.79–4.90) | 9.7 (1.8) | 1.75 (0.99–3.09) | 4.7* |

| ODD | 17.8 (4.0) | 1.78 (1.00–3.14) | 5.3 (1.2) | 1.39 (0.72–2.68) | 12.5 (4.1) | 1.90 (0.96–3.73) | 5.1* |

| Conduct Disorder | 16.9 (3.0) | 1.27 (0.80–2.00) | 6.1 (1.4) | 1.62 (0.87–3.00) | 10.8 (3.0) | 1.05 (0.53–2.08) | 0.0 |

| ADHD | 11.7 (2.0) | 0.99 (0.47–2.08) | 4.3 (1.4) | 0.93 (0.30–2.83) | 7.4 (1.4) | 1.06 (0.53–2.10) | 0.0 |

| Substance Use Disordersa | 17.4 (2.1) | 1.82 (1.06–3.11) | 6.1 (1.2) | 1.85 (0.89–3.87) | 11.4 (1.5) | 1.70 (0.90–3.22) | 0.3 |

| Alcohol Use Disorders | 17.5 (2.2) | 0.60 (0.31–1.16) | 4.6 (1.3) | 0.42 (0.20–0.89) | 12.9 (2.0) | 0.83 (0.38–1.78) | 0.0 |

| Drug Use Disorders | 20.1 (2.5) | 2.87 (1.60–5.15) | 7.2 (1.5) | 3.11 (1.47–6.58) | 13.0 (1.7) | 2.36 (1.15–4.84) | 4.2* |

Note: P values based on Wald chi-square tests. ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; aOR=Models adjusted for adolescent sex, age, and other emotional and behavioral disorders (but the disorder of interest); CI = confidence interval; GAD=generalized anxiety disorder; ODD=oppositional defiant disorder; PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder; SAD=separation anxiety disorder; SE = standard error.

Reports based on adolescent Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; n=10,123).

Reports based on adolescent CIDI and parent self-administered questionnaire sample (n=6,483).

p ≤ 0. 05;

p ≤ 0. 01;

p ≤ 0.001

Analysis of psychiatric correlates by subtype showed that the likelihood of comorbidity was consistently greater among adolescents with generalized vs. non-generalized social phobia. In particular, adolescents with generalized social phobia displayed higher rates of specific phobia (12.8%, SE=1.3% vs. 7.3%, SE=0.8%), agoraphobia (27.0%, SE=6.2% vs. 5.5%, SE=2.0%), panic disorder (20.5%, SE=4.1% vs. 6.7%, SE=3.0%), SAD (18.1%, SE=3.1% vs. 9.3%, SE=1.9%), ODD (12.5%, SE=4.1% vs. 5.3%, SE=1.2%), and drug use disorders (13.0%, SE=1.7% vs. 7.2%, SE=1.5%). Patterns of comorbidity by subtype also showed a number of variations. In particular, generalized social phobia displayed unique associations with agoraphobia and panic disorder and non-generalized social phobia displayed a unique positive association with PTSD and a unique negative association with alcohol use disorders. Parallel 12-month comorbidity estimates demonstrated a similar pattern of results, with minor exceptions (not shown, but available on request).

Discussion

Results of this nationally representative study of adolescents indicate that social phobia is a highly prevalent, persistent, and impairing mental disorder among adolescent youth, closely resembling the magnitude and severity of this condition among adults.3–5,33 In addition, findings suggest that while the performance only subtype of social phobia appears to be quite rare among adolescents, generalized social phobia is both a common and clinically relevant form of social phobia in this adolescent age range. Adolescents with the generalized subtype not only evidenced higher levels of severity and disability relative to adolescents with non-generalized social phobia, but they experienced this degree of clinical severity over longer periods.

As reported in our earlier work,22 we found that approximately 9% of youth in the U.S. experience social phobia at some point in their lifetime. Although the prevalence estimate of social phobia revealed in these data approximates previous studies of youth,1 this rate is slightly lower than the 12.1% rate observed among U.S. adults in the National Comorbidity Survey – Replication (NCS-R).34 Nevertheless, converging with findings from both adult3,5 and youth surveys,4,6,7 we found that social phobia in any form was associated with marked levels of impairment and persistence. Likewise, our results regarding the comorbidity of social phobia with other anxiety disorders closely parallel previous community studies of adults34,35 and youth.4,6,7 Our failure to find significant associations between social phobia and mood or alcohol use disorders after controlling for comorbid disorders, however, suggests that these relations may be due in part to other psychopathology. It is also possible that the secondary risk for these conditions among affected individuals is not yet evident during the adolescent years, instead emerging during adulthood.36,37

In line with previous investigations of adults34 and youth,10 more than half (55.8%) of adolescents with lifetime social phobia exhibited fear of most social situations, consistent with the DSM-IV/DSM-V definition of generalized social phobia. In addition to its common presentation, adolescents characterized with generalized social phobia demonstrated greater morbidity and clinical severity relative to adolescents who failed to endorse a fear of most social situations. These youth displayed an earlier age of onset, experienced a higher degree of disability and impairment, and were more likely to have a variety of other psychiatric disorders, relative to adolescents with non-generalized social phobia. Such findings extend prior work with exclusively adult samples,34,38–41 and strongly replicate one previous study of German youth.4 While it is clear that individuals who fear a greater number of situations evidence greater clinical pathology, several previous studies have contested the presence of qualitative (as opposed to quantitative) distinctions between individuals with and without generalized social phobia.34,42,43 Moreover, the matter of whether generalized social phobia is best defined by a particular number of fears or whether it should instead be conceptualized along a continuum of severity continues to be an outstanding empirical question.43,44 Although beyond the scope of this study, future work on this topic will examine how various thresholds may function to identify individuals with more severe and pervasive forms of the disorder.

Providing some support for retaining DSM-5 definitions of generalized social phobia, patterns of sociodemographic correlates appeared to differ across recognized subtypes. Such variations in sociodemographic correlates by subtype may partly explain inconsistent findings of previous community and international studies of youth.4,6–9,12 In line with this notion, general population studies of adults have found a higher proportion of females to evidence generalized social phobia and a greater number of males to evidence non-generalized social phobia.34,42 Further, while both subtypes of social phobia displayed associations with specific phobia, SAD, and drug use disorders, several psychiatric disorders showed unique associations with only one subtype. Similar to our findings, previous studies of youth have also found unique associations between generalized social phobia and agoraphobia4 and between non-generalized social phobia and PTSD.10 Taken together, these results highlight the heterogeneity of social phobia and the need to investigate psychiatric correlates of various presentations in the future.

In contrast to the large proportion of adolescents affected with the generalized subtype, less than 1% of youth with social phobia displayed a fear profile consistent with the proposed DSM-5 performance only subtype. Yet, higher proportions of performance only social phobia have been observed in studies involving participants of older ages.11,39,45 These findings suggest that public speaking (and performance) fears may only become clinically significant with the greater opportunity for avoidance that characterizes adulthood. For instance, whereas youth are often required by caretakers and teachers to engage in public speaking activities, adults retain the ability to avoid such situations. The demand to participate in public speaking activities may provide youth more occasions for exposure, consequently resulting in performance anxiety habituation and lower prevalence rates. Alternatively, it is possible that adolescents who exhibit clinically significant public speaking and performance fears fail to do so in the absence of other clinical-level social fears. Prospective research will be useful in providing further information on variations in the nature and magnitude of social fears across development.

Several limitations of the current study deserve comment. First, given that clinical information on social phobia was acquired exclusively from adolescents via retrospective reports, interview data may be subject to both informant and recall biases. Yet, because the onset of social phobia closely coincides with the age of participants in the present study, respondents may be less vulnerable to such reporting errors.3,7 Further, the current study supplemented interview questions with additional probes that have been found to increase the recall accuracy of psychiatric disorder onset.29 In addition, the cross-sectional study design prohibits examination of longitudinal associations between social phobia and observed correlates, emphasizing the need for prospective general population studies of youth in the future.

Even with these limitations, the current study is the first to examine the lifetime prevalence and associated features of social phobia in a large, nationally representative sample of U.S. adolescents. In addition, this study provides novel information on the scale, impact, and potential utility of the proposed DSM-5 social phobia subtypes among U.S. adolescent youth. In consideration of the extremely low rate of performance only social phobia among adolescents, additional work is necessary to evaluate the impact of modifications to this subtype. For example, some studies involving youth with social phobia have found that approximately one-quarter to one-third are affected primarily with performance fears when a broader definition is employed.11,46 Therefore, revisions to the proposed DSM-5 subtype may benefit from inclusion of a number of additional performance fears appropriate to this age range (e.g., speaking in class when a teacher calls on you, taking an important test or exam, etc.). Quite the opposite, the proposed generalized subtype of social phobia appears to identify a large number of affected youth who experience a distinct illness course and level of clinical severity. Despite the degree of impairment associated with generalized social phobia, it is notable that less than one-fifth of these youth had ever contacted a professional concerning their social fears. Such a substantial discrepancy calls critical attention to the importance of enhancing public awareness and access to evidence based interventions for social phobia in adolescents.47 The observed increase in generalized social phobia as adolescents advance into adulthood further highlights this period as an opportune time for the prevention of future risk.

Acknowledgments

The National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (U01-MH60220) and the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01 DA016558) with supplemental support from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust. The NCS-A was carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: Drs. Burstein, Albano, Avenevoli, and Merikangas and Ms. He and Ms. Kattan report no biomedical or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Marcy Burstein, Genetic Epidemiology Research Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Mental Health

Jian-Ping He, Genetic Epidemiology Research Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Mental Health

Gabi Kattan, Genetic Epidemiology Research Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Mental Health

Anne Marie Albano, Columbia University Medical Center

Shelli Avenevoli, Division of Developmental Translational Research, National Institute of Mental Health

Kathleen R. Merikangas, Genetic Epidemiology Research Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Mental Health

References

- 1.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009 Sep;32(3):483–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beesdo K, Bittner A, Pine DS, et al. Incidence of social anxiety disorder and the consistent risk for secondary depression in the first three decades of life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Aug;64(8):903–912. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittchen HU, Fehm L. Epidemiology and natural course of social fears and social phobia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2003;(417):4–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s417.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wittchen HU, Stein MB, Kessler RC. Social fears and social phobia in a community sample of adolescents and young adults: prevalence, risk factors and co-morbidity. Psychol Med. 1999 Mar;29(2):309–323. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fehm L, Pelissolo A, Furmark T, Wittchen HU. Size and burden of social phobia in Europe. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005 Aug;15(4):453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Frequency and comorbidity of social phobia and social fears in adolescents. Behav Res Ther. 1999 Sep;37(9):831–843. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ranta K, Kaltiala-Heino R, Rantanen P, Marttunen M. Social phobia in Finnish general adolescent population: prevalence, comorbidity, individual and family correlates, and service use. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(6):528–536. doi: 10.1002/da.20422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canino G, Shrout PE, Rubio-Stipec M, et al. The DSM-IV rates of child and adolescent disorders in Puerto Rico: prevalence, correlates, service use, and the effects of impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004 Jan;61(1):85–93. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gren-Landell M, Tillfors M, Furmark T, Bohlin G, Andersson G, Svedin CG. Social phobia in Swedish adolescents : prevalence and gender differences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009 Jan;44(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piqueras JA, Olivares J, Lopez-Pina JA. A new proposal for the subtypes of social phobia in a sample of Spanish adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22(1):67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knappe S, Beesdo-Baum K, Fehm L, Stein MB, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Social fear and social phobia types among community youth: Differential clinical features and vulnerability factors. J Psychiatr Res. 2010 May 29; doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003 Aug;60(8):837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Frequency of panic attacks and panic disorder in adolescents. Depress Anxiety. 1999;9(1):19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bittner A, Egger HL, Erkanli A, Jane Costello E, Foley DL, Angold A. What do childhood anxiety disorders predict? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007 Dec;48(12):1174–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998 Jan;55(1):56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Course and outcome of anxiety disorders in adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16(1):67–81. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Last CG, Perrin S, Hersen M, Kazdin AE. A prospective study of childhood anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996 Nov;35(11):1502–1510. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chavira DA, Stein MB. Recent developments in child and adolescent social phobia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000 Aug;2(4):347–352. doi: 10.1007/s11920-000-0080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Assocation. American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Development. [Accessed 10/01/2010];2010 http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=163.

- 20.Merikangas K, Avenevoli S, Costello J, Koretz D, Kessler RC. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): I. Background and measures. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Apr;48(4):367–369. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819996f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, et al. Design and field procedures in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009 Jun;18(2):69–83. doi: 10.1002/mpr.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Oct;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Green J, et al. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): III. Concordance of DSM-IV/CIDI diagnoses with clinical reassessments. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Apr;48(4):386–399. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819a1cbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grills AE, Ollendick TH. Issues in parent-child agreement: the case of structured diagnostic interviews. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2002 Mar;5(1):57–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1014573708569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green JG, Avenevoli S, Finkelman M, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: concordance of the adolescent version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI) with the K-SADS in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent (NCS-A) supplement. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010 March;19(1):34–49. doi: 10.1002/mpr.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27(2):93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knauper B, Cannell CF, Schwarz N, Bruce ML, Kessler RC. Improving the accuracy of major depression age of onset reports in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1999;8:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011 Jan;50(1):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN: Professional software for survey data analysis. 10 ed. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. 2nd ed. New York City: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler RC. The impairments caused by social phobia in the general population: implications for intervention. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2003;(417):19–27. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s417.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruscio AM, Brown TA, Chiu WT, Sareen J, Stein MB, Kessler RC. Social fears and social phobia in the USA: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2008 Jan;38(1):15–28. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Stein MB. Considering comorbidity in social phobia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003 Dec;38(12):728–734. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0720-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sonntag H, Wittchen HU, Hofler M, Kessler RC, Stein MB. Are social fears and DSM-IV social anxiety disorder associated with smoking and nicotine dependence in adolescents and young adults? Eur Psychiatry. 2000 Feb;15(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stein MB, Fuetsch M, Muller N, Hofler M, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Social anxiety disorder and the risk of depression: a prospective community study of adolescents and young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001 Mar;58(3):251–256. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furmark T, Tillfors M, Stattin H, Ekselius L, Fredrikson M. Social phobia subtypes in the general population revealed by cluster analysis. Psychol Med. 2000 Nov;30(6):1335–1344. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kessler RC, Stein MB, Berglund P. Social phobia subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1998 May;155(5):613–619. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.5.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holt CS, Heimberg RG, Hope DA. Avoidant personality disorder and the generalized subtype of social phobia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992 May;101(2):318–325. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stein MB, Chavira DA. Subtypes of social phobia and comorbidity with depression and other anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord. 1998 Sep;50 Suppl 1:S11–S16. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Gabalawy R, Cox B, Clara I, Mackenzie C. Assessing the validity of social anxiety disorder subtypes using a nationally representative sample. J Anxiety Disord. 2010 Mar;24(2):244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stein MB, Torgrud LJ, Walker JR. Social phobia symptoms, subtypes, and severity: findings from a community survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000 Nov;57(11):1046–1052. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bogels SM, Alden L, Beidel DC, et al. Social anxiety disorder: questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010 Feb;27(2):168–189. doi: 10.1002/da.20670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein MB, Walker JR, Forde DR. Public-speaking fears in a community sample. Prevalence, impact on functioning, and diagnostic classification. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996 Feb;53(2):169–174. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830020087010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hofmann SG, Albano AM, Heimberg RG, Tracey S, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Subtypes of social phobia in adolescents. Depress Anxiety. 1999;9(1):15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albano AM, DiBartolo PM. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Social Phobia in Adolescence. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]