Abstract

Television (TV) viewing is associated with an increased risk in childhood obesity. Research surrounding food habits of tweens largely bypass snacking preferences while watching TV in the home. The aim of this cross-sectional study was to describe snacking prevalence by tween gender, and to describe parental rules surrounding snacking while watching TV at home. Survey data were obtained in 2008 from 4th through 6th grade students (N=1557) who attended 12 New England schools. Complete self-reported measures (N=1448) included demographics, household and bedroom TV ownership, TV watching frequency, snacking prevalence, snacking preferences, and parental rules regarding snacking while watching TV. Comparisons were generated using chi-square analyses. Overall, the majority of children (69.2%) snacked “sometimes” or “always” during TV viewing, with the majority of responses (62.9%) categorized as foods. The most popular food snacks for both genders in this sample were salty snacks (47.9%), with fruits and vegetables ranking a distant second (18.4%). Girls (22.6%) selected fruits and vegetables more frequently than boys (14.7%), P=0.003. Of those drinking beverages (n=514), boys selected sugar-sweetened beverages more often than girls (43.5% versus 31.7%), P=0.006, and girls chose juice more often than boys (12.3% versus 6.1%), P=0.02. Overall, approximately half (53.2%) of students consumed less healthy snacks while watching TV. Interventions for parents and both genders of tweens focusing on healthful snacking choices may have long-term beneficial outcomes.

Keywords: child or adolescent, food and beverage, gender, television

INTRODUCTION

Approximately one in three children in America are currently categorized as overweight or obese, with nearly half of those (17%) meeting criteria for childhood obesity (ie, ≥ 95th percentile of body mass index) (1). Despite awareness of the childhood obesity epidemic, dietary quality of youth in the US continues to decline (2-6). Adolescents consume more fat and sugars from snack foods and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) than ever before (3-5), with increased snacking associated with increased intake (5). Reports suggest that nearly one-quarter of adolescents’ calories may be consumed by snacking (5). Thus, although many Americans eat more energy than necessary (4), the prevalent foods consumed lack essential nutrients.

The home media environment, especially through television (TV), may play a role in the childhood obesity risk. Children spend an average of three to four hours watching TV every day (7), which includes an average of 21 food or beverage advertisements often promoting energy-dense, nutrient-poor options (8). It has also been found that children with TVs in their bedrooms are at higher risk for being overweight (9). At least one study suggests a relationship between the home media environment and eating behaviors. Barr-Anderson and colleagues (10) reported that adolescents with a bedroom TV tended to have lower vegetable consumption (ie, females), lower fruit intake (ie, males), and all reported eating fewer family meals and drinking more SSBs. Overall, youth exposure to TV has been positively correlated with energy intake (11), including snacking (12-15) and meals (16-18), as well as fast-food consumption (19, 20), and negatively associated with fruit, vegetable, and dairy consumption (10, 11, 19, 21) and participation in family meals (10). In fact, the Institute of Medicine recently concluded that American youths are at high risk for being influenced by food marketing on TV (22). Despite these concerns, research to date has not examined snacking patterns in pre-teens while watching TV in the home environment.

Food preferences and dietary intake of youths have also been shown to differ by gender. Research suggests boys consume higher amounts of energy dense fruits and vegetables (e.g., fried potatoes) as compared to girls (2), adolescent boys may drink more SSBs and snack more often than girls (23), and that females report a higher preference of vegetables (24). In line with this research, Caine-Bish and Scheule (25) found that of those from grades 3-12, females tended to prefer fruits and vegetables in the school environment, while males preferred high protein items like meat. Although differences between gender in food habits of youths have been shown in the aforementioned research, none to our knowledge have reported gender differences in snacking preferences while watching TV of those from grades 4-6 while in the home environment. Tweens, which are “in between” childhood and adolescence, differ from younger and older youths physically, cognitively, and socially (26), which makes them a prime target for healthy behavioral interventions.

The aim of this research is to report the prevalence of tween snacking while watching TV, as well as categorize the content of foods and beverages routinely consumed. Gender comparisons for both foods and beverages are described, which may be used in the future to better target healthy eating habits for tweens.

METHODS

Study Design and Subjects

Cross-sectional data in this study were collected from 4th, 5th, and 6th grade students living in New Hampshire (NH) and Vermont (VT) from March to May 2008 to better understand the role that media plays in the nutritional and health habits of tweens by geographic location (e.g. rural and urban), age, and gender. Fifteen public elementary and middle schools were selected by convenience sample to oversample rural schools, in order to reflect the combined states demographic. Classification of location was based on the United States Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC), with eight rural schools rating 7-9 by county on the RUCC, and four urban schools rating 2-3 (27). Each school participating (n=12) was offered a $250 stipend. All 4th-6th graders enrolled in the schools were eligible for participation in the study. Parents were sent an advance letter that detailed the study and procedure, instructing them to call the school or principal investigator if they did not want their child to participate in the study. Three parents called or emailed to request more information about the study, but no parents declined consent. In addition to parental consent, students had the opportunity to decline participation (n=9). The paper-and-pencil surveys were administered to 1557 students by our trained research staff in the classroom, and took approximately 45 minutes to complete. Students were offered token incentives (ie, water bottles, pens, pencils) following completion of the survey. The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College approved the study.

Measures

Media survey questions for this study were based on Brown et al.’s Teen Media project for grades 7-8 (28, 29). These questions were slightly modified to reflect updated TV programming and media devices, and to account for the younger age group using input from 10 focus groups conducted by our research team in 2007 from grades 4–6 from three middle schools in NH and VT (n=115). The survey components addressed here include: 1) demographics, household and bedroom TV ownership, and TV watching frequency, 2) snacking prevalence and frequency while viewing TV, 3) content of foods and beverages reported while viewing TV, and 4) parental rules surrounding snacking behaviors while watching TV.

Demographics, Media Ownership and Usage

Tweens were asked, “What grade are you in?” to determine grade level. Self-identity of gender was established by having each tween indicate if they were a boy or girl. For media ownership, tweens were asked the following open-ended question: “How many of these (e.g., TV with cable or satellite, TV without cable or satellite) are in your house?” For bedrooms, respondents were asked, “Think of things you have in your own bedroom. How many of these are in your bedroom?” Responses were coded as mutually exclusive in the bedroom (i.e., no, yes without cable/satellite, yes with cable/satellite). Frequency of TV watching on school days was measured by asking students, “How many hours do you watch TV on a normal school day.” Answers ranged from < one, to ≥ five hours daily. Based on the American Academy for Pediatrics recommendations (30), responses were collapsed to ≤ two hours and > two hours daily for analyses.

Prevalence and frequency of snacking while watching TV

To measure prevalence and frequency of snacking, tweens were asked, “I eat or snack while watching TV.” The response categories were “Always,” “Sometimes,” “Almost Never,” or “Never.” Data were collapsed into a variable of “low” [Almost never/Never] and “high” [Sometimes/Always] snacking frequency for analyses.

Perceived Parental Rules Surrounding Snacking Behaviors During TV

Parental rules were assessed using two questions: “My parents/guardians tell me when I can eat snacks at home,” and “I have to eat the snacks that my parents/guardians tell me.” Similarly, responses for both questions were “Always,” “Sometimes,” “Almost Never,” or “Never,” and were dichotomized into “low” [Almost Never/Never] and “high” [Sometimes/Always] levels.

Food and beverage content of snacking preferences

Tweens were asked food and beverage preferences with the following open-ended question: “Write 1 or 2 foods that you eat or drink most often while watching TV.” The number of responses was recorded with a range from zero to two. To enable independence of observation assumptions, and because some students (n=113) did not answer twice, only the first item was coded. Based on literature surrounding food and beverage categories of children and adolescents (31-34), items from the first list were organized initially by 1) food, or 2) beverage. The first author (MSM) coded the responses as follows:

Foods

Subcategories for foods were classified as the following: 1) breads/grains including non-cereal breakfast items (e.g., toaster pastries, waffles, pancakes), 2) cereals/cereal bars, 3) soups/sandwiches, 4) confections/candies (eg, candy, gum), 5) convenience/frozen meals/pizza, 6) dairy products (eg, milk, yogurt, cheese excluding desserts), 7) fruits and vegetables, 8) meat and nuts, 9) salty snacks, 10) sweet snacks/desserts, and 11) fast food, and 12) other as specified.

Beverages

Subcategories for beverages were classified as the following: 1) no/low calorie (i.e., unsweetened coffee, tea, water, “diet” drinks, all < 40 calories per serving), 2) milk, 3) juice, and 4) SSB or soda.

Statistical Analysis

All survey data were entered into Microsoft Excel and then analyzed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics (version 18.0.0, Chicago, IL). Subjects with incomplete data were removed for the final analyses presented (n=1448), and only those responding to food (n=873) and beverage (n=514) content were considered for statistical analyses accordingly. Descriptive statistics and frequencies were generated for all variables. Categorical data were analyzed using chi-square tests, with the alpha level set at 0.05 (two-sided).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The 1448 participants ranged from grades 4-6, with approximately one-half of the sample (48.6%) girls (Table 1). Nearly two-thirds (63.2%) of the tweens lived in a rural setting, with the majority (61.9%) reporting three or more TV sets per home. Approximately two-thirds (62.6%) of the tweens in this study reported having a television in their bedroom, with 18.6% of those also reporting cable and/or satellite reception. Nearly two-thirds (64.3%) of the respondents reported watching ≤ two hours of TV per day during the school week, with no differences in viewing frequency by either gender (Table 1), or by school location (χ2=0.01; P=0.96). Boys were more likely than girls (P<0.001) to have a TV with cable or satellite reception accessible in their bedroom. Additionally, 65.3% of boys reported a TV in their bedroom with or without cable or satellite, compared to 59.7% of girls with or without cable or satellite (χ2=4.95; P=0.03). More tweens reported their parents were routinely involved in regulating the timing of snacks (64.5%) versus the content (48.8%), in which parents/guardians told them which snacks they “had to eat/drink.” There were no respective differences in either “low” or “high” parental involvement of snack timing or content by gender (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of tweens by gender.

| Characteristics | Girl n = 704 (48.6)a |

Boy n = 744 (51.4)a |

P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade Level | |||

| 4th | 249 (35.4) | 230 (30.9) | |

| 5th | 226 (32.1) | 238 (32.0) | 0.114 |

| 6th | 229 (32.5) | 276 (37.1) | |

| School location | |||

| Rural | 434 (61.6) | 482 (64.8) | |

| Urban | 270 (38.4) | 262 (35.2) | 0.216 |

| TVs in the Hoem | |||

| 0 | 20 (2.8) | 27 (3.6) | |

| 1 | 104 (14.8) | 118 (15.9) | 0.349 |

| 2 | 150 (21.3) | 133 (17.9) | |

| 3+ | 430 (61.1) | 466 (62.6) | |

| TV in the Bedroom | |||

| No | 284 (40.3) | 258 (34.7) | |

| Yes without Cable/Satellite |

318 (14.5) | 319 (22.4) | <0.001*** |

| Satellite | 102 (45.2) | 167 (42.9) | |

|

Frequency of TV

Viewing Daily During School Week |

|||

| ≤ 2 hours | 443 (62.9) | 488 (65.6) | |

| > 2 hours | 261 (37.1) | 256 (34.4) | 0.290 |

|

Parents regulate

the timing of snacks at home c |

|||

| Low | 238 (33.8) | 276 (37.1) | |

| High | 466 (66.2) | 468 (62.9) | 0.191 |

|

Parents regulate

snack content c |

|||

| Low | 352 (50.0) | 390 (52.4) | |

| High | 352 (50.0) | 354 (47.6) | 0.357 |

|

Snacking

Frequency While Watching TV c |

|||

| Low | 205 (29.1) | 241 (32.4) | |

| High | 499 (70.9) | 503 (67.7) | 0.178 |

Percents add 100 by column for gender.

Based on χ2 test for categorical data, with **p-value significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed),

p-value significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed).

For two level variables: “Low” = Almost Never or Never, and “High” = Sometimes or Always.

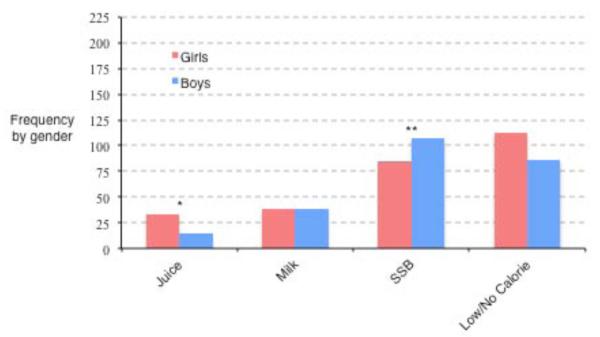

Snacking frequency did not differ by gender, with greater than two-thirds of respondents (69.2%) reporting they snacked “sometimes or always” with TV (Table 1). However, those that reported watching more TV (n=514; 35.7%) also reported snacking “sometimes or always” more often (n=407; 78.7% versus n=595; 59.4%), χ2=34.22; P<0.001. Overall, the sample reported a total of 873 (62.9%) food and 514 (37.1%) beverage snacks. Nearly two-thirds of tweens (n=934; 64.5%) did not report drinking beverages while watching TV. However, among those who indicated consuming beverages (n=514), girls reported drinking more juice (P=0.02), whereas boys reported drinking sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) more frequently (P=0.006). Although girls reported drinking low or no calorie beverages more frequently than boys (41.8% versus 35% respectively), there was no statistical difference (P=0.11). Milk intake did not vary by gender, and comprised 14.8% of all beverages in total. However, the most nutrient dense choices, milk and juice, made up less than one-quarter (24.1%) of the total beverages consumed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Favorite snack beverage categories of tweens by girls (pink/gray) and boys (blue/black) while watching TV (n = 514). SSB=Sugar sweetened beverage. * Chi-square P value < 0.05. ** Chi-square P value < 0.01

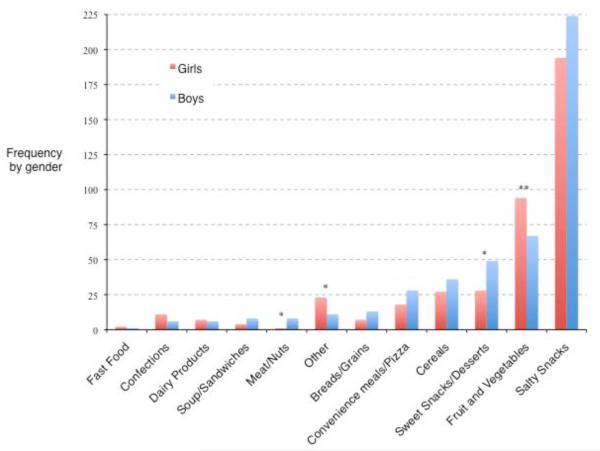

By far, both boys (49%) and girls (46.6%) reported consuming salty snacks most often (n=418), including chips, pretzels, and popcorn (Figure 2). The second most popular category included a range of fruits and vegetables (n=161), and girls (22.6%) reported fruit or vegetable consumption more often than boys (14.7%), P=0.003. Other than desserts/sweet snacks for boys (10.7%), all remaining food categories for both genders were less than 10% of the total. Quick-serve restaurant (ie, fast-food) responses were negligible (n=3). Boys reported eating significantly more meats (P=0.03) and desserts (P=0.04) than girls. Girls, on the other hand, reported snacking on ”other foods” (i.e., mainly dinner, or not otherwise specified), P=0.02, as compared to boys.

Figure 2.

Favorite snack food categories of tweens by girls (pink/gray) and boys (blue/black) while watching TV (n = 873). * Chi-square P value < 0.05. ** Chi-square P value < 0.01

Results from this survey show snacking prevalence “sometimes” or “always” while watching TV to be high (69.2%), and that those watching more TV are more likely to report snacking more frequently. Tween girls tended to select nutrient-dense, lower-energy foods (ie, more fruits and vegetables) more often than boys for snacking while watching TV. However, both genders favored salty food snacks over all other categories. Similar to adolescent reports (5), tweens reported selecting salty snacks over fruits and vegetables nearly three-to-one, and a staggering 32-to-one of salty snacks to dairy products, like yogurt or cheese. For adolescents in 2005-2006, the top-rated snacks of grain, vegetable, and oils groups were tortilla, corn chips, and/or potato chips respectively, with carbonated soft drinks leading the groups of discretionary calories and added sugars (5). Of note, boys in this sample also reported drinking SSBs more often than girls, with girls consuming juice more often. These results are consistent with other research reporting adolescent boys drink more soft drinks than girls (23, 35), and that females consume more juice than males (35). There were no differences between stated parental rules surrounding snacking with TV by gender.

Although the preference of nutrient-poor, energy-dense foods and beverages of children and adolescents is consistent with other research (4,5), this study offers hope that some tweens might be open to interventions encouraging healthful eating, given that fruits and vegetables were a distant second in the food category. These results align with Caine-Bish and Scheule’s study (25) that found girls tended to select fruits and vegetables at school, and boys were more likely to report choosing meat products. In this study, nine students selected meat or nut products (Figure 2); boys reported 100% (n=8) of the meat products, with the remaining answer “nuts” (n=1) reported by a girl.

Differences in snacking behaviors could be attributed to a number of possibilities. Recently, experts concluded that food and beverage advertising alters children’s dietary preferences and choices (22), which may affect boys and girls differently. Anschultz, Engels, and Van Strien recently (12) found that boys 8-12 years old consumed more food when exposed to these cues on commercials, as compared to non-food commercials and female peers. Another possibility could be that pre-adolescent girls perceive worse health than their male peers, which could lead them towards positive lifestyle changes earlier (36). Yet another possibility relates to the prevalence of dieting (i.e., restrictive eating patterns) and negative eating attitudes in pre-adolescent females. Previous research reports the prevalence of female tween dieting ranges anywhere in between 30-50% (37-39), with age-related increasing trends. Although restrictive eating patterns, including vegetarianism, have been associated with increased fruit and vegetable consumption, they have also been correlated with an increased risk of disordered eating behaviors, including binging and unhealthful weight control activities (40). Thus, care needs to be taken in promoting healthful dietary patterns to emphasize a healthy lifestyle instead of an ideal image or weight. Finally, research suggests that for both genders, eating in front of a TV may minimize physiological cues that signal satiety to the individual’s body, which could influence discretionary intake and increase risk for obesity (41, 42).

The present study should be considered in the context of limitations. First of all, although our survey measures contain face validity from focus groups, they have not been measured against a gold standard, given the lack of research on tween segments. Media questions were limited to TV and did not include cell phones, computers, or other media devices. Because TV viewing frequency estimates did not take into account these other non-traditional media platforms, the frequency of watching TV may be underestimated. Secondly, generalizability may be limited due to the regional population sampled. Although rural oversampling was representative in this area, this would not extend to all geographic locations. Future research should encompass a wider scope of children, including body mass indices, from different geographic regions. We also rely on the accuracy of self-reported measures and perceptions, which lend themselves to memory biases and may interject errors of measurement (43). For example, we were unable to discern whether “juice” responses were 100% juice or otherwise, or the accuracy of tween perceptions regarding parental involvement. However, other researchers use similar measures to garner information from youth (9, 18, 28, 44), and although social desirability may bias responses, answers may be more truthful because total dietary recall or intake was not tallied (45). Additionally, we did not assess socioeconomic status, which has been shown to correlate to food accessibility and dietary quality (2). However, we surveyed students in public schools, with greater than 99% participation, suggesting that we captured the general population within these areas. Lastly, amounts or portion sizes of snacks were not collected, and specific nutritional information could not be calculated. Therefore, “nutrient-poor, energy-dense” assumptions come from general categories of foods and beverages. Future research should include quantitative measurements of snacks in the home to determine the absolute and relative contribution of intake during TV viewing, as compared to overall eating patterns in context of parental regulation. Also, future studies should examine the frequency and amount of food intake based on TV food advertising exposure (i.e., amount, type, and timing) in the tween population. Strengths of this study include a large rural sample size of the tween population, as well as snacking habits in conjunction with TV viewing.

CONCLUSIONS

This study found some gender differences in snacking behaviors while watching TV for tweens in 4th-6th grades. Although reported parental rules around snacking-related timing and food content were similar for both genders, the types of foods and beverages consumed varied by gender. Tween girls tended to eat more fruits and vegetables, and drank more juice, whereas boys preferred meats, desserts, and sugar-sweetened beverages. However, the majority of all tweens favored salty-snacks, and roughly one-half of those in middle school could greatly improve dietary selections during a sedentary activity. Given increasing independence and the concurrent development of self-identity during the tween years, awareness of tween preferences can help target healthy eating behaviors during snack times for long-term beneficial outcomes.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007-2008. JAMA. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lorson BA, Melgar-Quinonez HR, Taylor CA. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intakes in US children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009 Mar;109(3):474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicklas TA, Elkasabany A, Srinivasan SR, Berenson G. Trends in nutrient intake of 10- year-old children over two decades (1973-1994) : the Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 May 15;153(10):969–977. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.10.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 Oct;110(10):1477–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center. Food Surveys Research Group Snacking Patterns of U.S. Adolescents: What we eat in America, NHANES 2005-2006. Food Series Research Group Data Brief. 2010 Available from: http://ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=19476.

- 6.Kimmons J, Gillespie C, Seymour J, Serdula M, Blanck HM. Fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents and adults in the United States: percentage meeting individualized recommendations. Medscape J Med. 2009;11(1):26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rideout V, Foehr U, Roberts D. Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8-18 Year Olds. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Menlo Park, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gantz W, Schwartz N, Angelini JR, Rideout V. Food for Thought: Television Food Advertising to Children in the United States. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Menlo Park CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adachi-Mejia AM, Longacre MR, Gibson JJ, Beach ML, Titus-Ernstoff LT, Dalton MA. Children with a TV in their bedroom at higher risk for being overweight. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007 Apr;31(4):644–651. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barr-Anderson DJ, van den Berg P, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Characteristics associated with older adolescents who have a television in their bedrooms. Pediatrics. 2008 Apr;121(4):718–724. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matheson DM, Killen JD, Wang Y, Varady A, Robinson TN. Children’s food consumption during television viewing. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Jun;79(6):1088–1094. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anschutz DJ, Engels RC, Van Strien T. Side effects of television food commercials on concurrent nonadvertised sweet snack food intakes in young children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 May;89(5):1328–1333. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halford JC, Boyland EJ, Hughes GM, Stacey L, McKean S, Dovey TM. Beyond-brand effect of television food advertisements on food choice in children: the effects of weight status. Public Health Nutr. 2008 Sep;11(9):897–904. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007001231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halford JC, Gillespie J, Brown V, Pontin EE, Dovey TM. Effect of television advertisements for foods on food consumption in children. Appetite. 2004 Apr;42(2):221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris JL, Bargh JA, Brownell KD. Priming effects of television food advertising on eating behavior. Health Psychol. 2009 Jul;28(4):404–413. doi: 10.1037/a0014399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blass EM, Anderson DR, Kirkorian HL, Pempek TA, Price I, Koleini MF. On the road to obesity: Television viewing increases intake of high-density foods. Physiol Behav. 2006 Jul 30;88(4-5):597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coon KA, Goldberg J, Rogers BL, Tucker KL. Relationships between use of television during meals and children’s food consumption patterns. Pediatrics. 2001 Jan;107(1):E7. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldman S, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Associations between watching TV during family meals and dietary intake among adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007 Sep-Oct;39(5):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.04.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller SA, Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gillman MW. Association between television viewing and poor diet quality in young children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2008;3(3):168–176. doi: 10.1080/17477160801915935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taveras EM, Sandora TJ, Shih MC, Ross-Degnan D, Goldmann DA, Gillman MW. The association of television and video viewing with fast food intake by preschool-age children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006 Nov;14(11):2034–2041. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boynton-Jarrett R, Thomas TN, Peterson KE, Wiecha J, Sobol AM, Gortmaker SL. Impact of television viewing patterns on fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003 Dec;112(6 Pt 1):1321–1326. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity? National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wouters EJ, Larsen JK, Kremers SP, Dagnelie PC, Geenen R. Peer influence on snacking behavior in adolescence. Appetite. 2010 Aug;55(1):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granner ML, Sargent RG, Calderon KS, Hussey JR, Evans AE, Watkins KW. Factors of fruit and vegetable intake by race, gender, and age among young adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2004 Jul-Aug;36(4):173–180. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caine-Bish NL, Scheule B. Gender differences in food preferences of school-aged children and adolescents. J Sch Health. 2009 Nov;79(11):532–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegel D, Coffey T, Livingston G. The Great Tween Buying Machine: Marketing to Today’s Tweens. Paramount Market Publishing, Inc; Ithaca, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [Accessed October 28, 2010];Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. 2004 http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/RuralUrbanContinuumCodes/

- 28.L’Engle KL, Pardum CJ, Brown JD. Accessing adolescents: a school-recruited, home-based approach to conducting media and health research. J Early Adolesc. 2004;24(2):144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown JD, Pardum CJ. Little in common: Racial and gender differences in adolescents’ television diets. J Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2004;48(2):266–278. [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Academy of Pediatrics Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics. 2001 Feb;107(2):423–426. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batada A, Seitz MD, Wootan MG, Story M. Nine out of 10 food advertisements shown during Saturday morning children’s television programming are for foods high in fat, sodium, or added sugars, or low in nutrients. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008 Apr;108(4):673–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gamble M, Cotugna N. A quarter century of TV food advertising targeted at children. American Journal of Health Behavior. 1999;23(4):261–267. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell LM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ. Exposure to food advertising on television among US children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007 Jun;161(6):553–560. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sutherland LA, Mackenzie T, Purvis LA, Dalton M. Prevalence of Food and Beverage Brands in Movies: 1996-2005. Pediatrics. 2010 Feb 8; doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Storey ML, Forshee RA, Anderson PA. Beverage consumption in the US population. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2006 Dec;106(12):1992–2000. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cavallo F, Zambon A, Borraccino A, Raven-Sieberer U, Torsheim T, Lemma P. Girls growing through adolescence have a higher risk of poor health. Qual Life Res. 2006 Dec;15(10):1577–1585. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Weight control behaviors and dietary intake among adolescents and young adults: longitudinal findings from Project EAT. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009 Nov;109(11):1869–1877. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McVey G, Tweed S, Blackmore E. Dieting among preadolescent and young adolescent females. CMAJ. 2004;170(10):1559–1561. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Packard P, Krogstrand KS. Half of rural girls aged 8 to 17 years report weight concerns and dietary changes, with both more prevalent with increased age. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002 May;102(5):672–677. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson-O’Brien R, Perry CL, Wall MM, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Adolescent and young adult vegetarianism: better dietary intake and weight outcomes but increased risk of disordered eating behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009 Apr;109(4):648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellissimo N, Pencharz PB, Thomas SG, Anderson GH. Effect of television viewing at mealtime on food intake after a glucose preload in boys. Pediatr Res. 2007 Jun;61(6):745–749. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e3180536591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hetherington MM, Anderson AS, Norton GN, Newson L. Situational effects on meal intake: A comparison of eating alone and eating with others. Physiol Behav. 2006 Jul 30;88(4-5):498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papper RA, Holmes ME, Popovich MN. Middletown Media Studies. Florida State University; Tallahassee: 2004. Spring [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eisenmann JC, Bartee RT, Smith DT, Welk GJ, Fu Q. Combined influence of physical activity and television viewing on the risk of overweight in US youth. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008 Apr;32(4):613–618. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klesges LM, Baranowski T, Beech B, et al. Social desirability bias in self-reported dietary, physical activity and weight concerns measures in 8- to 10-year-old African-American girls: results from the Girls Health Enrichment Multisite Studies (GEMS) Prev Med. 2004 May;38(Suppl):S78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]