Abstract

The amino-terminal arginine-rich motif of the phage HK022 Nun protein binds phage λ nascent mRNA transcripts while the carboxy-terminal domain binds RNA polymerase and arrests transcription. The role of specific residues in the carboxy-terminal domain in transcription termination were investigated by mutagenesis, in vitro and in vivo functional assays, and NMR spectroscopy. Coordination of zinc to three histidine residues in the carboxy-terminus inhibited RNA binding by the amino-terminal domain; however, only two of these histidines were required for transcription arrest. These results suggest that additional zinc-coordinating residues are supplied by RNA polymerase in the context of the Nun–RNA polymerase complex. Substitution of the penultimate carboxy-terminal tryptophan residue with alanine or leucine blocks transcription arrest, whereas a tyrosine substitution is innocuous. Wild-type Nun fails to arrest transcription on single-stranded templates. These results suggest that Nun inhibition of transcription elongation is due in part to interactions between the carboxy-terminal tryptophan of Nun and double-stranded DNA, possibly by intercalation. A model for the termination activity of Nun is developed on the basis of these data.

Keywords: Nun protein, transcription termination, RNA binding, DNA binding, zinc-binding motif

The 109-amino-acid Nun protein of bacteriophage HK022 binds to the BOXB sequence in the nascent transcripts of the λpL and pR operons and induces transcription termination (Robert et al. 1987). Nun activity is opposed to the activity of λ phage's own N protein, which binds to BOXB and acts as an antiterminator of transcription. BOXB is part of a larger NUT sequence that includes BOXA, a recognition site for the Escherichia coli NusB and NusE proteins. Host NusA, NusB, NusE, and NusG are required for Nun transcription termination in vivo (Robert et al. 1987; Robledo et al. 1991; Burova et al. 1999). In a purified in vitro transcription assay, Nun arrests transcription on a λ DNA template without releasing the DNA or the RNA transcript (Hung and Gottesman 1995). RNA polymerase (RNAP) in the Nun-arrested complex fails to translocate either away from or toward the promoter, but retains a fully functional catalytic center. The 3′ terminal nucleotide of the nascent transcript can turn over in the arrested complex: It is removed by pyrophosphate and restored by the appropriate NTP (Hung and Gottesman 1995, 1997). Although not absolutely required in vitro, host Nus proteins stimulate Nun arrest and reduce the need for high Nun concentrations.

Nun is a member of the arginine-rich motif (ARM) family of RNA-binding proteins. Other members of this family include the Tat and Rev proteins of HIV, and the N proteins of temperate bacteriophage (Weiss and Narayana 1998). Complexes of these proteins with their cognate RNA sequences are structurally diverse (Weiss and Narayana 1998). The structure of the amino-terminal ARM motif of Nun bound to λ BOXB (A.C. Stuart, M.E. Gottesman, and A.G. Palmer, in prep.) is similar to the λ N–BOXB complex (Legault et al. 1998). BOXB binding by the ARM is inhibited by the carboxy-terminal domain of Nun in the presence of Zn2+; in contrast, complex formation is stimulated by the binding of the E. coli NusA protein to the Nun carboxyl terminus (Watnick and Gottesman 1998).

The present paper investigates the role of specific amino acid residues in the carboxy-terminal domain of Nun in inhibition of BOXB binding and in transcription termination. We demonstrate that histidine residues located at positions 93, 98, and 100 in the Nun protein are required for Zn2+-dependent inhibition of BOXB binding and also play a role in Nun-dependent transcription termination and arrest. Furthermore, we present evidence that a tryptophan residue located at position 108 is necessary to block transcription elongation, possibly by interacting with the DNA template.

Results

1H NMR spectroscopy of carboxy-terminal peptide

To determine whether the three carboxy-terminal histidine residues, H93, H98, and H100, of Nun interact with Zn2+, we synthesized a wild-type 19-residue peptide corresponding to the Nun carboxy-terminal sequence V91–S109 (Fig. 1A) and a mutant H98A 19-residue peptide containing the His98 → Ala substitution. The peptides contain no other residues, such as cysteine, known to be capable of coordinating Zn2+. The interactions of these peptides with Zn2+ were monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy. The chemical shifts of the δ2 and ε1 imidazole protons of histidine have distinctive chemical shifts, near 7 ppm and 8 ppm, respectively (Cavanagh et al. 1996), and are sensitive to the chemical states of the imidazole δ1 and ε2 nitrogen atoms. Thus, they provide a marker for determining whether these residues interact with Zn2+ (Lee et al. 1992).

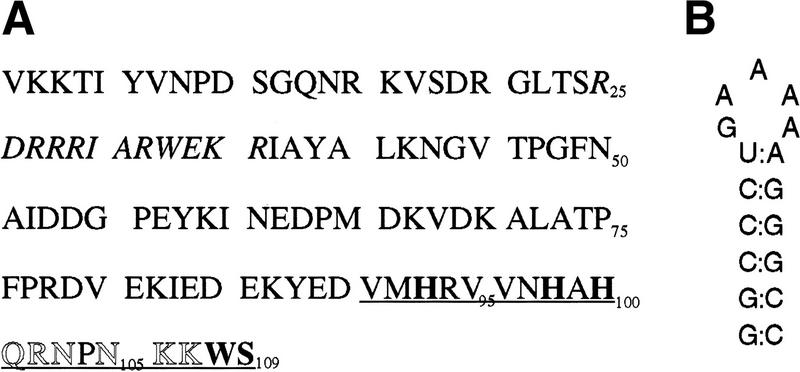

Figure 1.

(A) Amino acid sequence of Nun protein and (B) RNA sequence of λ BOXB. (A) The ARM region is italicized, the carboxy-terminal 19-amino-acid peptide used for 1H NMR spectroscopy is underlined, residues required for optimal Nun activity are in bold, and mutations known to have no effect on Nun activity are outlined. (B) Oligoribonucleotide that includes λ BOXB used in binding assays. The stem was elongated by an additional GC base pair to enhance stability.

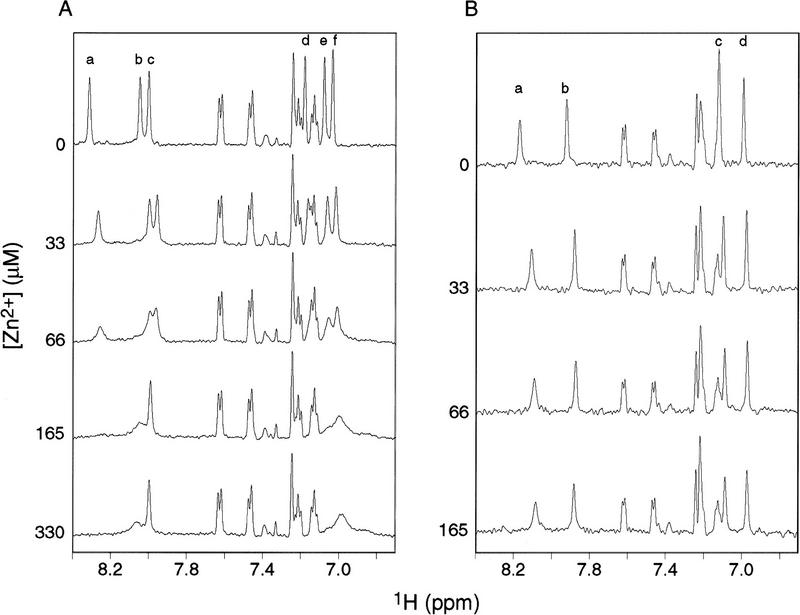

Wild-type (220 μm) and mutant H98A (100 μm) peptides were titrated with Zn2+ from 0 to ∼3 equivalents. Figure 2 shows one-dimensional spectra of the two peptides recorded as functions of [Zn2+]. After the initial addition of Zn2+, the ε1 resonances shifted upfield by ∼0.05 ppm, and the δ1 resonances shifted upfield by ∼0.02 ppm. This shift was not dependent on Zn2+ concentration and most likely represents a slight pH shift rather than interaction between the peptides and Zn2+. More significantly, the ε1 resonances labeled a and b and all three δ2 resonances for the wild-type peptide shown in Figure 2A became broader in a concentration-dependent manner as [Zn2+] was increased. The ε1 peaks a and b and δ2 peaks d and e were unobservable at [Zn2+] ≥ 165 μm. The δ2 peak f broadened and became indistinguishable from a large broad resonance at 7.02 ppm. The ε1 resonance labeled c initially broadened slightly and then narrowed at [Zn2+] ≥ 165 μm. A new broad ε1 resonance became visible at a shift of 8.05 ppm at [Zn2+] > 165 μm. The resonance at 8.05 ppm and the large broad resonance at 7.02 ppm arise from the Zn2+-bound peptide species. In contrast, the spectra for the mutant peptide, shown in Figure 2B, were nearly unaffected by [Zn2+]; only a very slight broadening of the resonances was observed even at the highest [Zn2+]. Twofold dilution of the final wild-type peptide sample containing 660 μm Zn2+ did not affect the NMR spectrum (data not shown); thus, the differences between the wild-type and mutant peptide NMR spectra reflect differences in Zn2+ affinities rather than differences in the peptide concentrations at which the two titrations were performed.

Figure 2.

Zn2+ titrations monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Regions of the NMR spectra containing the histidine imidazole resonances of the wild-type (A) and (B) H98A mutant 19-residue carboxy-terminal Nun peptide (B) are shown as functions of the indicated Zn2+ concentration. The wild-type peptide contains three histidine residues, H93, H98, and H100; the mutant peptide contains two histidine residues, H93 and H100. The wild-type peptide had a concentration of 220 μm and the mutant peptide had a concentration of 100 μm. (A) For the wild-type peptide in the absence of Zn2+, the histidine ε1 resonances have chemical shifts of 8.31 ppm (a), 8.05 ppm (b), and 8.00 ppm (c); the δ2 resonances have chemical shifts of 7.18 ppm (d), 7.08 ppm (e), and 7.04 ppm (f). (B) For the H98A mutant peptide in the absence of Zn2+, the histidine ε1 resonances have chemical shifts of 8.17 ppm (a) and 7.92 ppm (b); the δ2 resonances have chemical shifts of 7.12 ppm (c) and 7.00 ppm (d). For the wild-type peptide, the spectrum recorded at [Zn2+] = 660 μm was unchanged from the spectrum recorded at [Zn2+] = 330 μm; for the mutant peptide, the spectrum recorded at [Zn2+] = 330 μm was unchanged from the spectrum recorded at [Zn2+] = 165 μm (not shown). The individual resonances have not been specifically assigned to particular histidine residues in the Nun sequence. The unlabeled resonances in the spectra arise from the indole protons of W108.

Nun histidine residues have a role in termination

To determine whether Zn2+ binding affects transcription termination, the Nun histidine residues were altered by site-directed mutagenesis to alanine or serine, which cannot coordinate Zn2+, or to cysteine, which can. Plasmids expressing mutant Nun were introduced into an E. coli strain carrying a transcriptional fusion linking λ pL and nutL to a lacZ reporter (Burova et al. 1999). The efficiency of Nun termination was determined by β-galactosidase assay (Table 1). Substitution of H93 with alanine or cysteine or H100 with alanine, serine, or cysteine did not markedly reduce termination efficiency. However, substitution of H98 with alanine or serine virtually abolished termination activity.

Table 1.

Termination efficiency of Nun Zn2+ binding region mutants

| Mutation

|

β-Galactosidase (units)

|

Termination (%)

|

|---|---|---|

| pET21d | 515 | 0 |

| Wild-type Nuna | <1 | 100 |

| H93A | <1 | 100 |

| H98A | 448 | 13 |

| H100A | <1 | 100 |

| H93AH100A | 496 | 4 |

| H98C | 90 | 80 |

Strains were shifted from 32°C to 42°C for 60 min to induce pL and assayed for β-galactosidase. Uninduced levels were ⩽3 Miller units. Nun activity requires H or C at residue 98 and either H93 or H100. The strain used was 8473 (pL–nutL–lacZ).

pT7NunII was used as 100% termination for wild-type Nun.

A mutant substituted at H98 with cysteine retained 80% termination activity (Table 1). Substitution of both H93 and H100 with alanine reduced Nun termination efficiency 25-fold (Table 1), whereas Nun carrying cysteine at both sites was 85% as active as wild type (data not shown). Thus, termination activity requires that residue 98 and either residue 93 or 100 be capable of coordinating Zn2+.

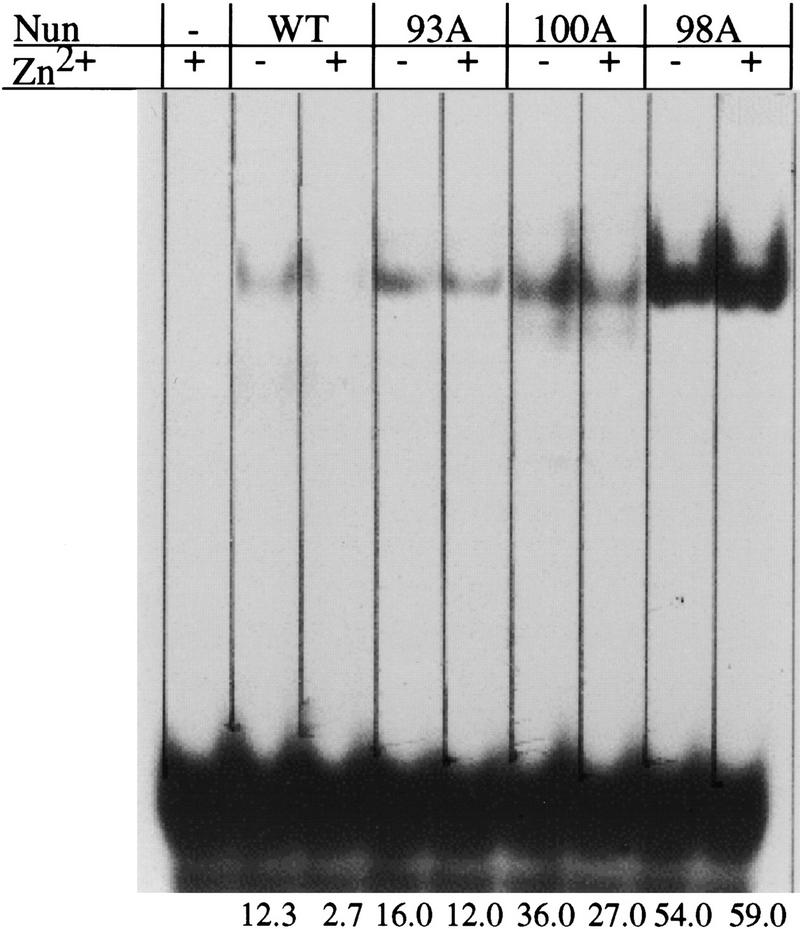

Zn2+inhibition of RNA binding requires the three carboxy-terminal histidines

Wild-type and mutant Nun were purified and tested for RNA binding by gel mobility shift assays (Fig. 3). As reported previously (Watnick and Gottesman 1998), the binding of wild-type Nun to 32P-labeled BOXB was strongly inhibited (four- to fivefold) by Zn2+. The H93A and H100A substitutions stimulated BOXB binding and rendered binding largely insensitive to Zn2+. The H98A substitution also stimulated BOXB binding and was entirely insensitive to Zn2+. These results indicate that Zn2+ coordination to the Nun carboxy-terminal H93, H98, and H100 residues inhibits RNA binding by the amino-terminal ARM motif. These results also imply that all three residues are required for Zn2+ binding.

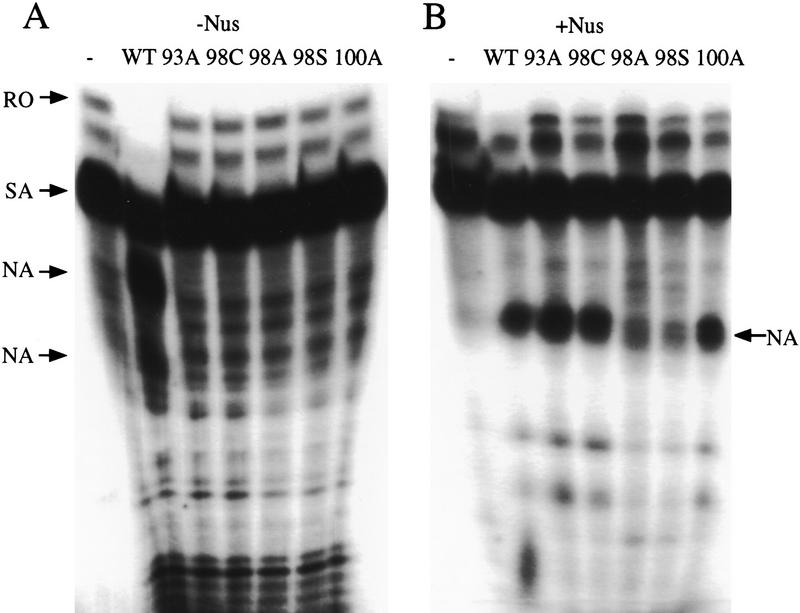

Figure 3.

Gel mobility shift assay. 32P-labeled BOXB (20 nm) was incubated with wild-type, H93A, H98A, H100A, and H98C Nun (500 nm) in the presence and absence of 5 μm Zn2+. The reactions were subjected to electrophoresis on a 7.5% native polyacrylamide gel. The wild-type protein is inhibited from binding BOXB by Zn2+, whereas mutant proteins H93A, H98A and H100A are not.

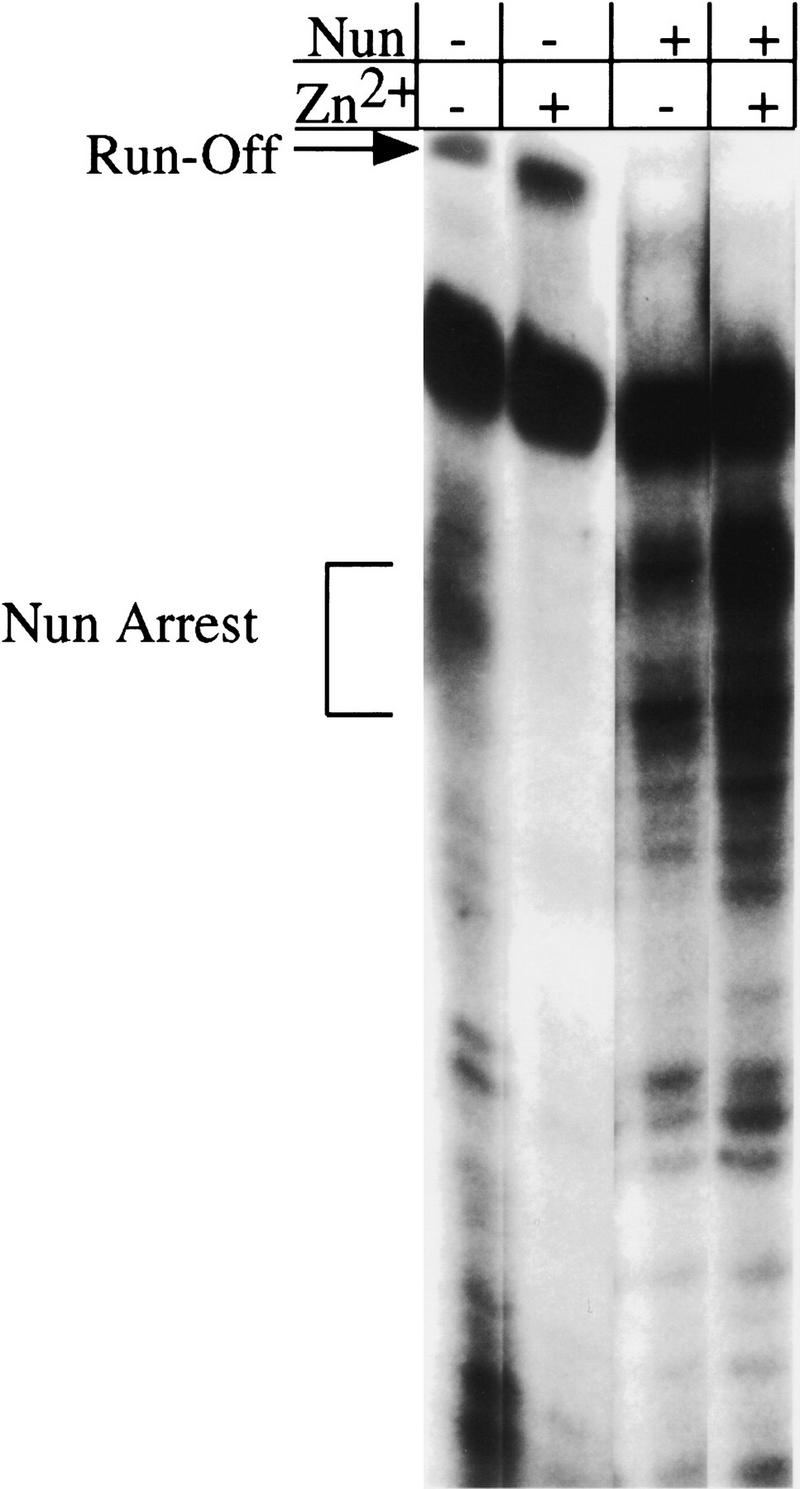

Histidine substitutions affect transcription arrest

The transcription arrest activity of the various Nun mutants was assayed in vitro (Fig. 4). None of the mutant proteins was active in the minimal transcription system (RNAP, Nun, template DNA, and NTPs). E. coli Nus A, B, E, and G factors restored activity to H93A, H100A, H93C and H98C, but not to H98A. This result is consistent with the termination phenotype of these mutants in wild-type nus+ bacteria. As reported previously, Nus factors enhance wild-type Nun activity (Hung and Gottesman 1995). Transcription arrest occurs earlier in the presence of Nus factors, as shown by the promoter-proximal shift of Nun-arrested transcripts.

Figure 4.

In vitro transcription assays for wild-type, H93A, H98A, H100A, and H98C Nun proteins. The transcription complexes were allowed to proceed to the +15 site on the template by withholding UTP. The reaction was then allowed to proceed to the runoff product by the addition of 10 μm NTPs, in the presence or absence of Nun or Nun mutants. Nus factors were added to final concentrations of 5 μm to mimic in vivo conditions (B). The band identified as SA is a spontaneously arrested complex that is sensitive to GreB (Hung and Gottesman 1995). The mutant proteins were capable of arresting transcription only in the presence of the Nus factors in contrast to the wild-type protein, which arrests both in the presence and absence of the Nus factors. (NA) Nun-arrested transcript; (SA) spontaneous (Nun-independent) arrested transcripts; (RO) run-off transcript.

Zn2+ stimulated transcription arrest by wild-type Nun in the minimal system (Fig. 5, lanes 3,4). Addition of Zn2+ enhanced arrest at the promoter-proximal arrest site. Note that the high Nun concentration used in this experiment obviated the requirement for BOXB binding. Zn2+ did not restore arrest activity to any of the Nun histidine mutants in the minimal transcription system (data not shown). Furthermore, Zn2+ also affected transcription in the absence of Nun. The addition of Zn2+ enhanced processivity; RNAP pausing was partially suppressed and the amount of runoff transcript increased (Fig. 5, lanes 1,2). Therefore, the RNAP used in this assay was probably not saturated with Zn2+.

Figure 5.

Effect of ZnCl2 on Nun transcription arrest. Transcription reactions were performed essentially as described in Fig. 4, except that at the elongation step (after +15) ZnCl2 was added, where indicated, at a concentration of 50 μm. Where indicated, Nun was added at 200 nm. The presence of ZnCl2 increased the efficiency of arrest by wild-type Nun, but had no effect on the activity of the mutant proteins.

W108 is critical for transcription arrest and termination

Carboxy-terminal to the histidine residues are three basic amino acids, R102, K106, and K107, followed by the penultimate tryptophan residue, W108. Nun carrying an alanine substitution in any one of these basic residues was termination proficient in vivo (data not shown). However, Nun substituted at W108 with alanine or a larger aliphatic residue, leucine, was inactive. In contrast, replacement of W108 with tyrosine, another aromatic amino acid, was permissible (Table 2).

Table 2.

Termination activity of Nun W108 substitution mutants

| Nun mutation

|

β-Galactosidase (units)

|

Termination (%)

|

|---|---|---|

| pET21d | 515 | 0 |

| Wild-type Nun | 1 | 100 |

| W108A | 587 | 2 |

| W108L | 882 | 0 |

| W108Y | 3 | 98 |

Control strains and all conditions were the same as those used in Table 1. Uninduced levels were ≤3 Miller units.

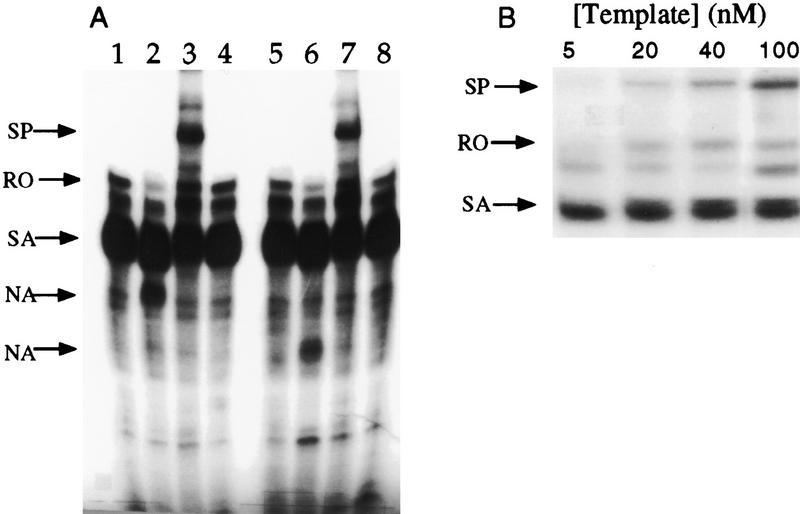

W108A induces template switching in vitro

Purified Nun W108A protein was tested for BOXB binding and transcription arrest. The affinity of mutant protein for BOXB was equivalent to wild-type Nun and was reduced by Zn2+ (data not shown). The phenotype of W108A in the in vitro transcription assay was, however, unexpected. The mutant protein failed to induce transcription arrest in either the minimal or the Nus-supplemented systems. Instead, W108A promoted the formation of a transcript approximately twice the length of the template (Fig. 6A, lanes 3,6). This RNA, we believe, is the product of template switching, which occurs when RNAP transfers to a second template without releasing nascent transcript (Nudler et al. 1996). The H98A mutation, which ablates transcription termination, also prevented template switching in the H98AW108A mutant (Fig. 6A, lanes 4,8). The efficiency of switching is dependent on template concentration (Nudler et al. 1996). RNAP unmodified by Nun can generate the switching product at high (100 nm) template concentrations (data not shown). W108A facilitates the intrinsic switching activity of RNAP so that it occurs efficiently at a fivefold lower template concentration (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

In vitro transcription. (A) In vitro transcription with RNAP in the absence of Nun (lane 1) and presence of wild-type (lane 2), W108A (lane 3), and H98AW108A (lane 4) Nun proteins in the absence of Nus factors (lanes 1–4). W108A Nun induces the production of a transcript approximately twice the length of the DNA template (SP) and does not arrest transcription at the sites where wild-type Nun does. H98AW108A Nun neither arrests transcription nor induces the production of the longer transcript. (Lanes 5–8) In vitro transcription with Nun proteins in the presence of the Nus factors. The Nus factors do not alter the activity of the mutant proteins. (B) Concentration dependence of W108A-induced template switching. Transcription was initiated with a template concentration of 5 nm and allowed to proceed to the +15 site on the template by withholding UTP; subsequently, the reaction was allowed to proceed to completion with the addition of 10 μm NTPs along with W108ANun. In this step, template concentration was supplemented to the levels indicated above the lanes. As template concentration was increased, the amount of the W108A-induced product was also increased. (RO) Runoff transcript; (SA) spontaneous (Nun-independent) arrest; (NA) Nun arrest; (SP) denotes switching product (W108A-induced transcript).

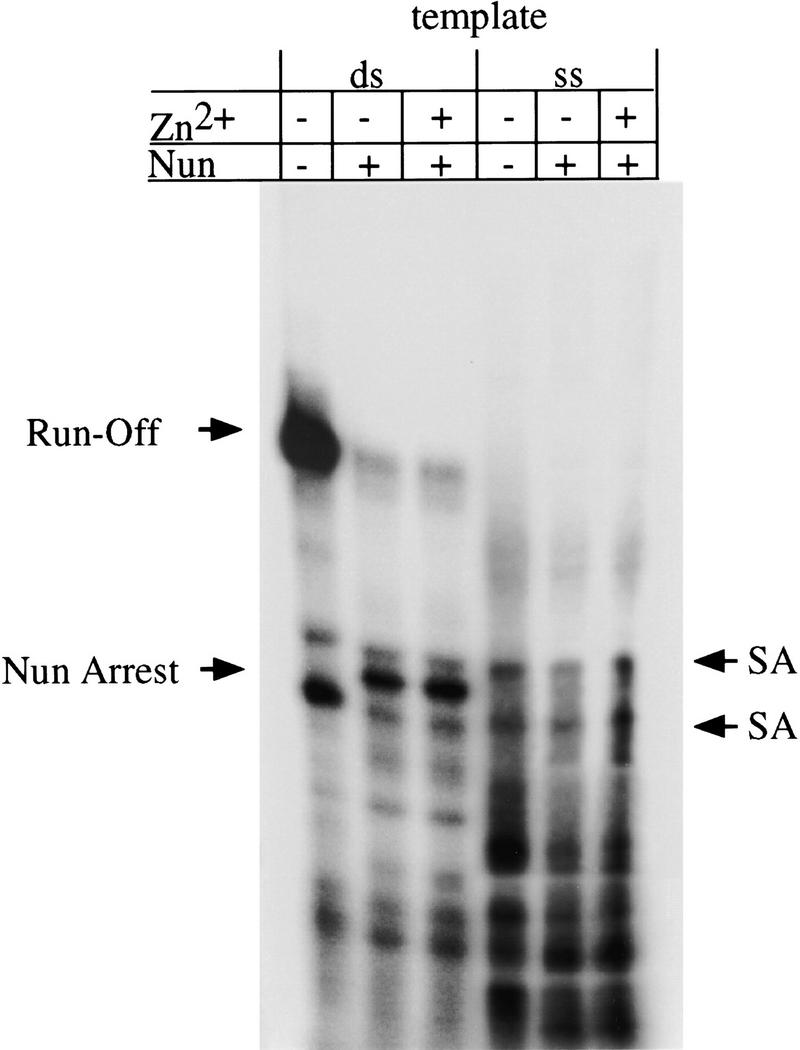

Nun cannot arrest transcription on single-stranded template

The requirement for a planar aromatic amino acid at residue 108 raised the possibility that Nun blocks translocation of RNAP through interactions of W108 with the DNA template. Tryptophan residues generally interact with double-stranded DNA either in base-stacking (intercalation) interactions or as groove binders. Thus, if Nun action requires an association between W108 and DNA template, Nun should only arrest transcription on double-stranded template. To test this hypothesis, we assayed Nun arrest on DNA that included a double-stranded promoter and a single-stranded template region. Nun was unable to arrest transcription on single-stranded DNA (Fig. 7). In contrast to control double-stranded template with the same sequence, no Nun-arrested transcript was visible using the single-stranded template. Furthermore, the bands representing the two spontaneous arrest sites (denoted as SA) flanking the Nun-arrest site are of equal intensities in the single-stranded template reaction in the presence and absence of Nun. This result is in contrast to the double-stranded template reaction in which Nun arrest selectively reduces the intensity of the band representing the promoter-proximal SA site.

Figure 7.

In vitro transcription of single-stranded (ss) and double-stranded (ds) templates. Transcription reactions were identical to those in Fig. 4 except that a doubled-stranded 110-bp template or a template with a 43-bp promoter and 77-nucleotide single-stranded region was used for the double-stranded and single-stranded transcription reactions, respectively. Where indicated, ZnCl2 (50 μm) was added. (SA) Spontaneous (Nun-independent) arrest.

Discussion

HK022 Nun and λ N proteins are similar in their amino-terminal ARM domains but share little carboxy-terminal homology (Weisberg and Gottesman 1999). Analysis of chimeric proteins indicates that Nun termination and N antitermination activities are specified by their carboxy-terminal domains (Henthorn and Friedman 1996). In the present work, we explore the roles of distinctive Nun carboxy-terminal amino acids in RNA binding, transcription arrest, and transcription termination.

We reported previously that Zn2+ inhibits Nun binding to λ RNA (Watnick and Gottesman 1998). Zinc fingers and other zinc binding motifs often participate in protein–nucleic acid interactions (Hanas et al. 1983; Brown et al. 1985; Miller et al. 1985; Preiss et al. 1985; Freedman et al. 1988). These motifs require at least four residues to coordinate Zn2+ (Berg 1990). Our data, based on NMR spectroscopy and RNA binding experiments, suggest that the three carboxy-terminal Nun histidine residues are sufficient for Zn2+ binding. We have not identified a fourth coordinating residue, and, other than solvent water molecules, no obvious candidates currently present themselves. Zn2+ coordination by three histidine residues (and a water molecule) in the active center of carbonic anhydrase has been reported (Christianson and Fierke 1996).

The changes in the 1H NMR spectrum of the wild-type peptide as the Zn2+ concentration is increased suggest a specific interaction between the wild-type peptide and Zn2+ that is absent in the H98A mutant peptide. The broadening of the free histidine imidazole resonances and appearance of new broad resonances during the titration suggests that the interaction with Zn2+ is slow, but probably near the intermediate exchange limit, on the NMR chemical shift time scale. The resonances for W108 are unaffected by Zn2+, which suggests that structural changes in the peptide due to Zn2+ interactions with the histidine residues do not affect the environment of W108.

In the presence of Zn2+, the carboxyl terminus strongly inhibits the association of the amino-terminal Nun ARM motif with BOXB RNA. We presume that Zn2+ alters the conformation of the carboxy-terminal domain so that it occludes the ARM motif. Inhibition by Zn2+ is overcome by binding of NusA to the Nun carboxyl terminus (Watnick and Gottesman 1998). Examples of DNA-binding proteins subject to interdomain regulation have been described previously (Chen et al. 1993).

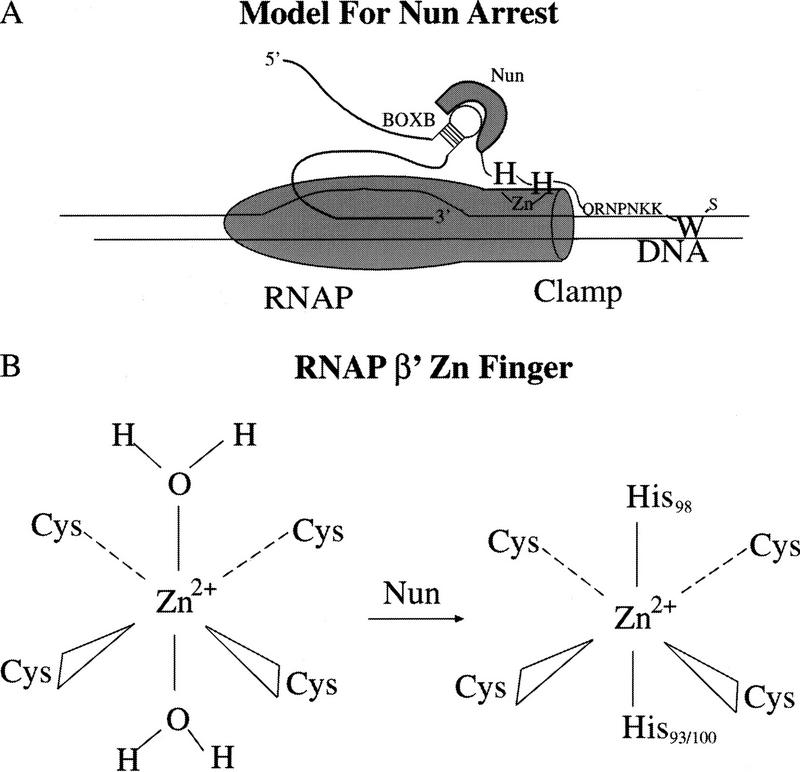

In contrast to RNA binding, Zn2+ stimulates Nun transcription arrest in vitro. Because we have not attempted to remove all Zn2+ from the reaction mixture, Nun-mediated arrest may be entirely Zn2+ dependent. Analysis of alanine substitution mutants indicates that only two of the three carboxy-terminal histidines, H98 and either H93 or H100, are sufficient for Nun arrest or termination. Cysteine substitution of the histidines yields functional Nun mutants, consistent with the hypothesis that Nun activity entails Zn2+ binding to the carboxyl terminus. The RNA binding data, however, suggest that free Nun needs all three histidines to coordinate Zn2+. We propose that a second protein, probably RNAP, provides the other Zn2+ ligands during transcription arrest/termination. Specifically, we propose that the zinc finger at the amino terminus (residues 57–92) of the RNAP β′ subunit and two of the Nun histidine residues participate in the coordination of Zn2+. X-ray absorption analysis indicates that Zn2+ in RNAP is found in atypical octahedral coordination, coordinated by six ligands rather than the usual four (Wu et al. 1992). Because only four conserved cysteines are located in this β′ subunit region, the other two ligands are likely to be water molecules. Two Nun histidines might displace the water molecules and coordinate Zn2+ in conjunction with these four cysteines. This scenario would provide a more stable coordination state for Zn2+, a soft Lewis acid, because the histidine nitrogen is a soft base, as opposed to H2O, which is a hard base.

The β′ subunit zinc finger lies in close proximity to the RNA transcript in the region immediately upstream from the DNA:RNA hybrid (Nudler et al. 1998). The role of the zinc finger in the amino terminus of the β′ subunit of E. coli RNAP in transcription elongation is unclear. In our experiments, Zn2+ enhanced RNAP processivity and stimulated Nun transcription arrest. Association of Nun with the zinc finger might help to stabilize the attachment of RNAP to DNA template. We demonstrated that template switching, which is due to failure of RNAP to dissociate at the end of the template, was stimulated by the arrest-defective Nun W108A mutant. A Nun-arrested complex was stable to 1.5 m KCl, whereas the paused complex from which it was derived dissociated at 0.15 m KCl (S. Hung and M.E. Gottesman 1997, and unpubl.).

Interestingly, the related HIV ARM protein, TAT, has been reported to bind to cyclin T via a zinc bridge (Wei et al. 1998). Zinc also stimulates TAT dimerization. Nun, however, does not appear to dimerize: It does not migrate as a dimer in native gels and binds to BOXB as a monomer as indicated by gel mobility shift assays. Furthermore, BOXB binding increases linearly with Nun concentration, indicating that dimerization is not a factor in Nun activity (Chattopadhyay et al. 1995b).

The penultimate residue of Nun is tryptophan, an amino acid that is usually located in the interior of proteins where it helps to form stable hydrophobic core regions. The location of W108 is consistent with a nonstructural role for this residue. We find that Nun W108A and Nun W108L are unable to arrest or terminate transcription. However, Nun W108A associates with RNAP, as determined by gel filtration (Watnick and Gottesman 1999), and promotes template switching. Template switching by Nun W108A is ablated by the H98A mutation. This evidence, coupled with the finding that wild-type Nun is unable to arrest transcription on single-stranded template, is consistent with the possibility that W108 interacts, possibly by intercalation, with DNA template in the Nun-arrested transcription complex. Several prokaryotic and eukaryotic proteins are known to intercalate into DNA. Intercalation of tryptophan, phenylalanine, methionine, or proline residues into the minor groove induces severe kinks in the DNA helix that play a major part in defining the biological role of the intercalating protein (Rice et al. 1996; Werner et al. 1996; Allain et al. 1999).

We have not ruled out, however, other possible interactions between W108 and the DNA template. For example IRF-1 binds its cognate DNA utilizing, among other motifs, a tryptophan cluster. Three of the five tryptophans in this cluster interact with the major groove of the DNA via hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts with the sugar phosphate backbone (Escalante et al. 1998). We note, however, that the Nun-induced arrest site is not dependent on template sequence, ruling out interactions between W108 and specific nucleotide residues (Hung and Gottesman 1997).

Our model of Nun action is presented in Figure 8. A Zn2+-dependent interaction between the carboxy-terminal histidines and the β′ subunit of RNAP is shown, as well as intercalation of the tryptophan 108 residue into template. A weakly conserved cysteine is found at residue 70, and a histidine is located at residue 80 of the β′ subunit of RNAP (Nudler et al. 1996). These residues are in the same region of the β′ subunit as the putative zinc finger and might be involved in coordinating Zn2+ in conjunction with Nun.

Figure 8.

(A) Model of Nun termination/arrest. Nun first binds to RNAP and coordinates a zinc ion(s) in conjunction with the zinc finger of the β′ subunit of RNAP. H98 and either H93 or H100 displace the two water molecules. The basic residues carboxy-terminal to the histidine residues then position W108 to interact with the DNA template and physically block translocation of RNAP. (B) Proposed model of Nun–RNAP zinc-binding interaction: H98 and H93/H100 displace water molecules coordinated to Zn2+ in β′ amino-terminal zinc finger.

The mode of Nun action described by Hung and Gottesman (1997) is consistent with the mechanism described above. Nun does not interfere with the ability of the RNAP active site to make or break phosphodiester bonds. Rather, it prevents RNAP from forward or backward translocation. Furthermore, we have previously established that wild-type Nun binds to the DNA template via photochemical cross-linking and copper-phenanthroline mediated cleavage, whereas the mutant W108A does not associate with template (Watnick and Gottesman 1999). We suggest that an intercalated or otherwise DNA-bound, tryptophan might act as a brake arm, inhibiting translocation. This interaction, along with Nun–RNAP interactions that enhance the binding of RNAP to DNA template, could account for the ability of Nun to arrest or terminate transcription.

Materials and methods

The H98A, H98C, H98S, H100A, H100C, H100S, W108A, W108L, and W108Y mutations were made via standard PCR mutagenesis techniques with a primer that annealed to the T7 promoter on the pT7NunII plasmid and a 3′ primer containing the desired mutation. The primers used to make these mutations were as follows: H98A,GGCGAAGCTTTTATGACCACTTTTTGTTTGGGTTTCGCTGGTGAGCGGCATTAACAAC; H98C,GCGGCGAAGCTTTTATGACCACTTTTTGTTTGGGTTTCGCTGGTGAGCGCAATTAACAAC; H98S, GCGGCGAAGCTTTTATGACCACTTTTTGTTTGGGTTTCGCTGGTGAGCGGAATTAACAAC; H100A, GCGGCGAAGCTTTTATGACCACTTTTTGTTTGGGTTTCGCTGGGCAGCGTGATTAACAAC; H100C, GCGGCGAAGCTTTTATGACCACTTTTTGTTTGGGTTTCGCTGGCAAGCGTGATTAACAAC; H100S, GCGGCGAAGCTTTTATGACCACTTTTTGTTTGGGTTTCGCTGGGAAGCGTGATTAACAAC; W108A, GCGCCGAAGCTTTTATGACGCCTTTTTGTTTGGG; W108L, GCGCCGAAGCTTTTATGACAACTTTTTGTTTGGG; and W108Y, GCGCCGAAGCTTTTATGAGTACTTTTTGTTTGGG. The H98AW108A double mutant was generated with the same primer as W108A with H98A Nun as a template. PCR products were purified from a 1% agarose gel, digested with NcoI and HindIII and ligated into the pET21d plasmid (Novagen), digested with the same enzymes, and treated with alkaline phosphatase. The H93A and H93C mutations were made by use of the Quikchange mutagenesis technique (Stratagene). The primers used to make the H93A mutation were GAGGATGTAATGGCCAGAGTTGTTAATCAC and GTGATTAACAACTCTGGCCATTACATCCTC and the primers used to make the H93C mutation were GAGGATGTAATGTGCAGAGTTGTTAATCAC and GTGATTAACAACTCTGCACATTACATCCTC.

Mutant Nun proteins were overexpressed and purified in the same manner as described previously for wild-type Nun (Chattopadhyay et al. 1995b; Watnick and Gottesman 1998). RNA binding gel shift assays were performed as described in Watnick and Gottesman (1998).

β-Galactosidase assays were performed in strain ZH1141 (Burova et al. 1999), carrying the λ pL and nutL regions upstream of a chromosomal lacZ reporter, as described. The strains were transformed with plasmids carrying the mutations made in the above procedures. Then, they were grown at 32°C to an OD600 between 0.2 and 0.6. At this time, 2 ml of culture was removed and the cells were centrifuged at 3500g in a Sorvall RC-2B centrifuge, and an additional 2 ml of culture was removed, added to 8 ml of media at 42°C, and incubated for 1 hr. The pellets were resuspended in Z buffer and disrupted with 10 μl of chloroform and 20 μl of 10% SDS. The solutions were the incubated at 28°C for 5 min after which time 200 μl of 4 mg/ml O-nitrophenyl galactopyranoside (ONPG) was added. The solutions were then incubated at 28°C for 2 hr more at which time 500 μl of 1 m CaCO3 was added to stop the reaction. The cells shifted to 42°C were treated in an identical fashion with the exception that the reaction was stopped 5 min after addition of ONPG.

The in vitro transcription assays were performed as described previously with the exception that the template concentration was 20 nm (Hung and Gottesman 1995, 1997). Template switching assays were performed with a template concentration of 5 nm at the initiation step. The template concentrations were adjusted after initiation by supplementing the template to final concentrations of 10, 20, 50, and 100 nm for the elongation step of the reaction. The 110-nucleotide template included λ pL (base pairs 35553–35594) fused to λ base pairs 35423–35492. Double-stranded template was made by annealing two 110-nucleotide complementary oligonucleotides. Single-stranded template was made by annealing an oligonucleotide consisting of λ base pairs 35553–35594 to the 110-nucleotide oligonucleotide described above. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Sigma Genosys.

Peptides for NMR spectroscopy were obtained from Tana Laboratories in lyophilized form. Wild-type peptide consisted of the 19 carboxy-terminal amino acids of Nun,VMHRVVNHAHQRNPNKKWS; the mutant peptide had the sequence VMHRVVNAAHQRNPNKKWS. Lyophilized peptides were dissolved in deuterated Tris buffer (10 mm, pH 7.3; Cambridge Isotopes) in 100% D2O (Isotec) and transferred to a Wilmad 528 NMR tube. The solution was lyophilized, the peptide was redissolved in 460 μl of 100% D2O, and the pH was adjusted to 7.3 (uncorrected for isotope effects). Peptide concentrations were determined by absorption spectroscopy on aliquots removed from the NMR tubes after completion of NMR spectroscopy. The wild-type peptide concentration was 220 μm, and the mutant peptide concentration was 100 μm. Zn2+ titrations were performed by adding aliquots from a 7.6 or 76 mm ZnCl2 (in 100% D2O) stock solution directly to the NMR tube. 1H NMR spectra were recorded for Zn2+ concentrations of 0, 33, 66, 165, 330, and 660 μm for the wild-type peptide and 0, 33, 66, 165, and 330 μm for the H98A mutant peptide. After the titration of the wild-type peptide was completed, the sample was diluted twofold to yield a peptide concentration of 110 μm and a Zn2+ concentration of 165 μm, and an additional NMR spectrum recorded.

1H NMR spectroscopy was performed at 285 K with a Bruker DRX500 spectrometer operating at a Larmor frequency of 500.13 MHz for the wild-type peptide and a DRX600 spectrometer operating at a Larmor frequency of 600.13 MHz for the H98A peptide. One-dimensional NMR spectra were acquired using a Hahn echo pulse sequence. (Rance and Byrd 1983; Davis 1989) The spectral width was 12,500 Hz, the data size was 8192 complex points, and 256 transients were acquired. The data were processed with a Lorentzian-to-Gaussian transformation, zero filled once, and Fourier transformed. The resulting spectra were phased, and the baseline was corrected with a polynomial of order 2. Processing was performed by use of Felix97 (MSI).

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Weisberg, Rodney King, and Stephen Kowalczykowski for their comments and suggestions. This work was supported by grants MCB-9722392 from the National Science Foundation to A.G.P. and National Institutes of Health grant GM37219 to M.E.G.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL gottesman@cuccfa.ccc.columbia.edu; FAX (212) 305-6900.

References

- Allain FH, Yen YM, Masse JE, Schultze P, Dieckmann T, Johnson RC, Feigon J. Solution structure of the HMG protein NHP6A and its interaction with DNA reveals the structural determinants for non-sequence-specific binding. EMBO J. 1999;18:2563–2579. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J. Zinc finger domains: Hypotheses and current knowledge. Annu Rev of Biophys & Biophys Chem. 1990;19:405–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.19.060190.002201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Sander C, Argos P. The primary structure of transcription factor TFIIIA has 12 consecutive repeats. FEBS Letters. 1985;186:271–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burova E, Hung SC, Chen J, Court DL, Zhou J-G, Mogilnitskiy G, Gottesman ME. E. coli mutations that block transcription termination by coliphage HK022 Nun protein. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1783–1794. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh J, Fairbrother WJ, Palmer AG, Skelton NJ. Protein NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and practice. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay S, Hung SC, Stuart AC, Palmer AG, Garcia-Mena J, Das A, Gottesman ME. Interaction between the phage HK022 Nun protein and the nut RNA of phage λ. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995b;92:12131–12135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Smit-McBride Z, Lewis S, Sharif M, Privalsky ML. Nuclear hormone receptors involved in neoplasia: erb A exhibits a novel DNA sequence specificity determined by amino acids outside of the zinc-finger domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2366–2376. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson D, Fierke C. Carbonic anhydrase: Evolution of the zinc binding site by nature and by design. Accounts Chem Res. 1996;29:331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Davis DG. Elimination of baseline distortions and minimization of artifacts from phased 2D NMR spectra. J Magn Reson. 1989;81:603–607. [Google Scholar]

- Escalante C, Yie J, Thanos D, Aggarwal A. Structure of IRF-1 with bound DNA reveals determinants of interferon regulation. Nature. 1998;391:103–106. doi: 10.1038/34224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman L, Luisi B, Korszun Z, Basavappa R, Sigler P, Yamamoto K. The function and structure of the metal coordination sites within the glucocorticoid receptor DNA binding domain. Nature. 1988;334:543–546. doi: 10.1038/334543a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanas JS, Hazuda DJ, Bogenhagen DF, Wu FY, Wu CW. Xenopus transcription factor A requires zinc for binding to the 5 S RNA gene. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:14120–14125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henthorn KS, Friedman DI. Identification of functional regions of the Nun transcription termination protein of phage HK022 and the N antitermination protein of phage γ using hybrid nun-N genes. J Mol Biol. 1996;257:9–20. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung SC, Gottesman ME. Phage HK022 Nun protein arrests transcription on phage λ DNA in vitro and competes with the phage λ N antitermination protein. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:428–442. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— The Nun protein of bacteriophage HK022 inhibits translocation of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase without abolishing its catalytic activities. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:2670–2678. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Palmer AG, Wright PE. Relationships between 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts and the secondary and tertiary structure of a zinc finger peptide. J Biomol NMR. 1992;2:307–322. doi: 10.1007/BF01874810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legault P, Li J, Mogridge J, Kay L, Greenblatt J. NMR structure of the bacteriophage lambda N peptide/boxB RNA complex: Recognition of a GNRA fold by an arginine-rich motif. Cell. 1998;93:289–299. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, McLachlan AD, Klug A. Repetitive zinc-binding domains in the protein transcription factor IIIA from Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1985;4:1609–1614. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudler E, Avetissova E, Markovtsov V, Goldfarb A. Transcription processivity: Protein–DNA interactions holding together the elongation complex. Science. 1996;273:211–217. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nudler E, Gusarov I, Avetissova E, Kozlov M, Goldfarb A. Spatial organization of transcription elongation complex in Escherichia coli. Science. 1998;281:424–428. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiss A, Rosenberg U, Kienlin A, Seifert E, Jackle H. Molecular genetics of Kruppel, a gene required for segmentation of the Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1985;313:27–32. doi: 10.1038/313027a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rance M, Byrd RA. Obtaining high fidelity spin 1/2 powder spectra in anisotropic media: Phase cycled Hahn-echo spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 1983;52:221–240. [Google Scholar]

- Rice PA, Yang S, Mizuuchi K, Nash HA. Crystal structure of an IHF-DNA complex: A protein-induced DNA U-turn. Cell. 1996;87:1295–1306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert J, Sloan SB, Weisberg RA, Gottesman ME, Robledo R, Harbrecht D. The remarkable specificity of a new transcription termination factor suggests that the mechanisms of termination and antitermination are similar. Cell. 1987;51:483–492. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90644-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robledo R, Atkinson BL, Gottesman ME. Escherichia coli mutations that block transcription termination by phage HK022 Nun protein. J Mol Biol. 1991;220:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90104-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watnick R, Gottesman ME. Escherichia coli NusA is required for efficient RNA binding by phage HK022 nun protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:1546–1551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watnick RS, Gottesman ME. Binding of transcription termination protein Nun to nascent RNA and template DNA. Science. 1999;286:2337–2339. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P, Garber M, Fang S, Fischer W, Jones K. A novel CDK9-associated C-type cyclin interacts directly with HIV-1 Tat and mediates its high-affinity, loop-specific binding to TAR RNA. Cell. 1998;92:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg RA, Gottesman ME. Processive antitermination. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:359–367. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.359-367.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MA, Narayana N. RNA recognition by arginine-rich peptide motifs. Biopolymers. 1998;48:167–180. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1998)48:2<167::AID-BIP6>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner MH, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Intercalation, DNA kinking, and the control of transcription. Science. 1996;271:778–784. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Huang W, Sinclair R, Powers L. The structure of the zinc sites of Escherichia coli DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25560–25567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]