Abstract

Ubiquitylation targets proteins for proteasome-mediated degradation and plays important roles in many biological processes including apoptosis. However, non-proteolytic functions of ubiquitylation are also known. In Drosophila, the inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (DIAP1) is known to ubiquitylate the initiator caspase DRONC in vitro. Because DRONC protein accumulates in diap1 mutant cells that are kept alive by caspase inhibition (“undead” cells), it is thought that DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation causes proteasomal degradation of DRONC, protecting cells from apoptosis. However, contrary to this model, we show here that DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation does not trigger proteasomal degradation of full-length DRONC, but serves a non-proteolytic function. Our data suggest that DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation blocks processing and activation of DRONC. Interestingly, while full-length DRONC is not subject to DIAP1-induced degradation, once it is processed and activated it has reduced protein stability. Finally, we show that DRONC protein accumulates in “undead” cells due to increased transcription of dronc in these cells. These data refine current models of caspase regulation by IAPs.

Author Summary

The Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis 1 (DIAP1) readily promotes ubiquitylation of the CASPASE-9–like initiator caspase DRONC in vitro and in vivo. Because DRONC protein accumulates in diap1 mutant cells that are kept alive by effector caspase inhibition—producing so-called “undead” cells—it has been proposed that DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation would target full-length DRONC for proteasomal degradation, ensuring survival of normal cells. However, this has never been tested rigorously in vivo. By examining loss and gain of diap1 function, we show that DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation does not trigger degradation of full-length DRONC. Our analysis demonstrates that DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation controls DRONC processing and activation in a non-proteolytic manner. Interestingly, once DRONC is processed and activated, it has reduced protein stability. We also demonstrate that “undead” cells induce transcription of dronc, explaining increased protein levels of DRONC in these cells. This study re-defines the mechanism by which IAP-mediated ubiquitylation regulates caspase activity.

Introduction

Ubiquitylation describes the covalent attachment of ubiquitin, a 76 amino acid polypeptide, to proteins which occurs as a multi-step process (reviewed in [1], [2]). E1-activating enzymes activate ubiquitin and transfer it to E2-conjugating enzymes. E3-ubiquitin ligases mediate the conjugation of ubiquitin from the E2 to the target protein. Repeated ubiquitylation cycles lead to the formation of polyubiquitin chains attached on target proteins. Polyubiquitylated proteins are delivered to the 26S proteasome for degradation. However, non-proteolytic roles of ubiquitylation have also been described (reviewed in [3], [4]). From E1 to E3, there is increasing complexity. For example, the Drosophila genome encodes only one E1 enzyme, termed UBA1, which is required for all ubiquitin-dependent reactions in the cell [5]. In contrast, there are hundreds of E3-ubiquitin ligases which are needed to confer substrate specificity.

Programmed cell death or apoptosis is an essential physiological process for normal development and maintenance of tissue homeostasis in both vertebrates and invertebrates (reviewed in [6]). A highly specialized class of proteases, termed caspases, are central components of the apoptotic pathway (reviewed in [7]). The full-length form (zymogen) of caspases is catalytically inactive and consists of a prodomain, a large and a small subunit. Activation of caspases occurs through dimerization and proteolytic cleavage, separating the large and small subunits. Based on the length of the prodomain, caspases are divided into initiator (also known as apical or upstream) and effector (also known as executioner or downstream) caspases [7]. The long prodomains of initiator caspases harbor regulatory motifs such as the caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD) in CASPASE-9. Through homotypic CARD/CARD interactions with the adapter protein APAF-1, CASPASE-9 is recruited into the apoptosome, a large multi-subunit complex, where it dimerizes and auto-processes leading to its activation [8], [9]. Activated CASPASE-9 cleaves and activates effector caspases (CASPASE-3, -6, and –7), which are characterized by short prodomains. Effector caspases execute the cell death process by cleaving a large number of cellular proteins [10].

In Drosophila, the initiator caspase DRONC and the effector caspases DrICE and DCP-1 are essential for apoptosis [11]–[18]. Like human CASPASE-9, DRONC carries a CARD motif in its prodomain [19]. Consistently, DRONC interacts with ARK, the APAF-1 ortholog in Drosophila (also known as DARK, HAC-1 or D-APAF-1) [20]–[22] for recruitment into an apoptosome-like complex which is required for DRONC activation [20], [23]–[31]. After recruitment into the ARK apoptosome, DRONC cleaves and activates the effector caspases DrICE and DCP-1 [25], [31]–[34].

Caspases are subject to negative regulation by inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) (reviewed in [35], [36]). For example, DRONC is negatively regulated by Drosophila IAP1 (DIAP1) [37], [38]. diap1 mutations cause a dramatic cell death phenotype, in which nearly every mutant cell is apoptotic, suggesting an essential genetic role of diap1 for cellular survival [39]–[41]. DIAP1 is characterized by two tandem repeats known as the Baculovirus IAP Repeat (BIR), and one C-terminally located RING domain [42]. The BIR domains are required for binding to caspases [37], [38], [43]. The RING domain provides DIAP1 with E3-ubiquitin ligase activity, required for ubiquitylation of target proteins [35], [36]. Importantly, the BIR domains can bind to caspases independently of the RING domain [37], [43].

Usually, IAPs bind to and inhibit activated, i.e. processed caspases, including CASPASE-3, CASPASE-7 and CASPASE-9 as well as the Drosophila caspases DrICE and DCP-1 (reviewed in [35], [36]). However, a notable exception to this rule is DRONC. DIAP1 binds to the prodomain of full-length DRONC [37], [38], [43]. This unusual behavior suggests an important mechanism for the control of DRONC activation. Indeed, it has been shown that the RING domain of DIAP1 ubiquitylates full-length DRONC in vitro [38], [44]. It has also been proposed that DIAP1 ubiquitylates auto-processed DRONC [33]. These ubiquitylation events are critical for the control of apoptosis, as homozygous diap1 mutants which lack a functional RING domain (diap1ΔRING) are highly apoptotic [41]. Because the BIR domains are intact in diap1ΔRING mutants, binding of DIAP1 to DRONC is not sufficient for inhibition of DRONC under physiological conditions, and ubiquitylation is the critical event for DRONC inhibition.

Although the importance of DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation of DRONC is well established, it is still unclear how this ubiquitylation event leads to inactivation of DRONC and of caspases in general. Because DRONC protein accumulates in diap1 mutant cells that are kept alive by expression of the effector caspase inhibitor P35, generating so-called ‘undead’ cells, it has been proposed that DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation triggers proteasomal degradation of full-length DRONC in living cells, thus protecting them from apoptosis [33], [38], [45], [46]. However, degradation of full-length DRONC in living cells has never been observed and non-degradative models have also been proposed [44]. Furthermore, ubiquitylation of mammalian CASPASE-3 and CASPASE-7 has been demonstrated in vitro [47]–[49]. However, evidence for proteasome-dependent degradation of these caspases in vivo, i.e. in the context of a living animal, is lacking. In fact, a non-degradative mechanism has been demonstrated for the effector caspase DrICE in Drosophila [50].

Here, we further characterize the role of ubiquitylation for the control of DRONC activation. Consistent with a previous report [44], we find that ubiquitylation of DRONC by DIAP1 is critical for inhibition of DRONC's pro-apoptotic activity. Using loss and gain of diap1 function, we provide genetic evidence that DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation of full-length DRONC regulates this initiator caspase through a non-degradative mechanism. We find that the conjugation of ubiquitin suppresses DRONC processing and activation. Interestingly, once DRONC is processed and activated, it has reduced protein stability. Finally, we show that dronc transcripts accumulate in P35-expressing ‘undead’ cells, accounting for increased DRONC protein levels in these cells. These data refine the current model of caspase regulation by IAPs.

Results

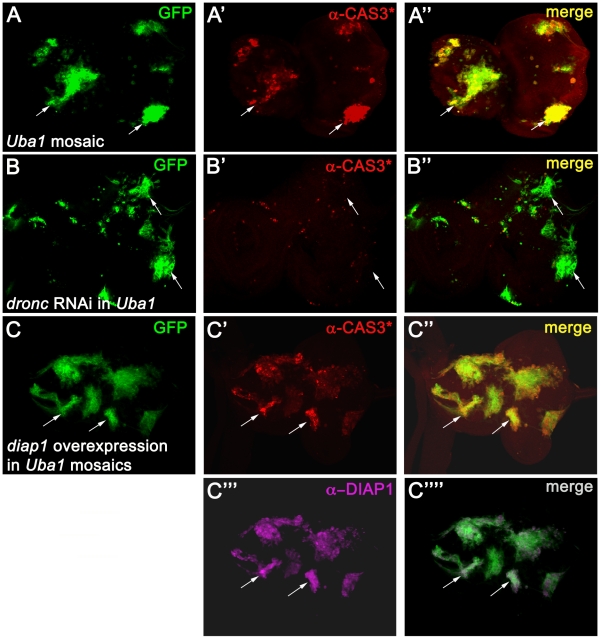

Overexpression of DIAP1 fails to suppress apoptosis of Uba1 mutant cells

It has previously been shown that complete loss of ubiquitylation due to mutations of the E1 enzyme Uba1 causes apoptosis in eye imaginal discs as detected by an antibody that recognizes cleaved, i.e. activated, CASPASE-3 (CAS3*) [5], [51], [52] (see also Figure 1A). Because ubiquitylation of DRONC does not occur in Uba1 mutants, we hypothesized that inappropriate activation of DRONC accounts for the apoptotic phenotype of Uba1 mutants. To test this possibility, we targeted dronc by RNA interference (RNAi) in Uba1 mutant cells in eye imaginal discs using the MARCM system and labeled for apoptosis using CAS3* antibody. In this system, Uba1 mutant cells expressing dronc RNAi are positively marked by GFP. Consistent with our hypothesis, knock-down of dronc strongly reduces apoptosis in Uba1 mutant clones (Figure 1B). Furthermore, we tested clones doubly mutant for Uba1 and ark, the Drosophila ortholog of APAF-1 that is required for DRONC activation (see Introduction). Apoptosis induced in Uba1 mutant clones is strongly suppressed if ark function is removed (Figure S1). These observations suggest that the apoptotic phenotype in Uba1 clones is caused by inappropriate activation of DRONC, presumably due to lack of ubiquitylation.

Figure 1. Apoptosis in Uba1 mutant clones is dependent on DRONC and cannot be inhibited by expression of DIAP1.

Shown are eye-antennal imaginal discs from third instar larvae. Posterior is to the right. In each panel, arrows highlight two representative clones. (A) Uba1 mosaic eye-antennal discs labeled for cleaved CASPASE-3 (α-CAS3*) antibody (red). These discs were incubated at 30°C 12 hours before dissection (see Material and Methods). Presence of GFP marks the location of Uba1 clones (see arrow). (B) TUNEL labeling of Uba1 mosaic eye-antennal imaginal discs expressing an RNAi transgene targeting dronc (UAS-droncIR (inverted repeat)) using the MARCM technique (see Material and Methods). Clones are positively marked by GFP. TUNEL-positive cell death is largely blocked by dronc knockdown (B′ and B″). (C) Strong overexpression of diap1 in Uba1 clones (magenta in C′″) fails to rescue the apoptotic phenotype, as visualized by CAS3* labeling (red in C′). Uba1 clones are marked by GFP due to the MARCM technique. Please note that diap1 is so strongly overexpressed in the clones that we had to adjust the settings in such a way that endogenous DIAP1 in wild-type tissue is below the detection limit (C′″). Genotypes: (A) hs-FLP UAS-GFP; FRT42D Uba1D6/FRT42D tub-Gal80; tub-GAL4. (B) hs-FLP UAS-GFP; FRT42D Uba1D6/FRT42D tub-Gal80; tub-GAL4/UAS-droncIR. (C) hs-FLP UAS-GFP/UAS-diap1; FRT42D Uba1D6/FRT42D tub-Gal80; tub-GAL4.

However, the protein levels of DIAP1 are increased in Uba1 mutant clones [5], [52]. There are two possibilities to explain the apoptotic phenotype in Uba1 mutants despite increased DIAP1 levels. First, the DIAP1 levels may not be sufficiently increased to inhibit DRONC. Alternatively, binding of DIAP1 to DRONC alone may not be sufficient for inhibition of DRONC; instead, ubiquitylation by DIAP1 is required to block DRONC activation, as previously suggested [44]. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we strongly overexpressed diap1 in Uba1 mutant clones in eye discs using the MARCM system and imaged for apoptosis by CAS3* labeling. Surprisingly, despite massive expression of diap1 (>20 fold over wild-type levels; Figure 1C′″), apoptosis still proceeds in Uba1 mutant clones (Figure 1C′), even though expression of the same transgene can block strong apoptotic phenotypes in several apoptotic paradigms (Figure S2). Apparently, overexpression of DIAP1 is not sufficient to inhibit DRONC and to protect Uba1 mutant cells from apoptosis. Because DIAP1 is the key regulator of DRONC and because DRONC is required for the apoptotic phenotype of Uba1 mutant cells, as evidenced by knock-down of dronc (Figure 1B), our data provide genetic evidence that binding of DIAP1 is not sufficient for DRONC inhibition in Uba1 mutant cells.

Consistent with this view, it has previously been shown that DIAP1 does ubiquitylate full-length DRONC in vitro [33], [38], [44]. We tested whether DIAP1 can also ubiquitylate DRONC in vivo. Because the available DRONC antibodies failed to immunoprecipitate endogenous DRONC, we transfected DRONC-V5 along with DIAP1+ or DIAP1ΔRING mutants (CΔ6, lacking the last six C-terminal residues, and F437A changing a critical Phe residue in the RING domain to Ala [53]) and His-tagged Ubiquitin into Drosophila S2 cells. Ubiquitylated proteins were affinity purified under denaturing conditions using Ni columns. The eluates were subsequently examined by immunoblotting with anti-V5 antibodies to detect ubiquitylated forms of DRONC. Under these conditions, DIAP1+ readily ubiquitylates full-length DRONC in S2 cells (Figure 2), whereas the RING mutants DIAP1CΔ6 and DIAP1F437A were significantly impaired in their ability to ubiquitylate DRONC (Figure 2). These results indicate that DIAP1 ubiquitylates full-length DRONC in a RING-dependent manner in cultured cells.

Figure 2. DIAP1 ubiquitylates DRONC in S2 cells.

DRONC C>A–V5 was coexpressed with His-Ub and the indicated DIAP1 constructs in S2 cells. Ubiquitylated proteins were purified and analyzed by immunoblot for ubiquitylated DRONC with V5 antibodies. Co-expression of DIAP1wt leads to higher molecular weight modification of DRONC, while the RING-ligase inactive mutants (CΔ6, F437A) cannot ubiquitylate DRONC. * marks non-modified DRONC that is due to unspecific DRONC:matrix association.

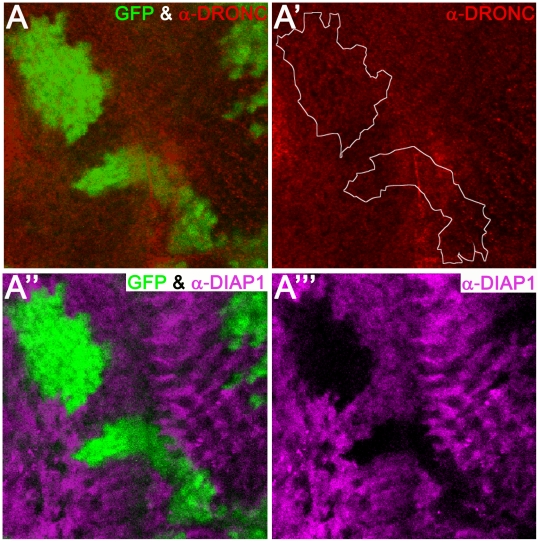

Overexpression of DIAP1 does not induce degradation of DRONC

Because DIAP1 readily ubiquitylates DRONC, it has been postulated that DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation leads to proteasomal degradation of DRONC [33], [38], [45]. However, this has never been rigorously tested in vivo. Therefore, we examined, whether overexpression of diap1 in wild-type animals can influence DRONC protein levels in vivo. To this end, we generated clones overexpressing diap1 (marked by absence of GFP) in eye discs, and analyzed the protein abundance of DRONC. Interestingly, despite high expression of diap1 (Figure 3A′″), the levels of DRONC remained unchanged and were not influenced by DIAP1 (Figure 3A′). The anti-DRONC antibody used in this assay is specific for DRONC (Figure S3). Importantly, the diap1 transgene used produces a functional DIAP1 protein that is able to inhibit apoptosis in several paradigms (Figure S2). Therefore, these data suggest that overexpressed DIAP1 does not target DRONC for degradation in living cells.

Figure 3. Overexpression of diap1 does not trigger degradation of DRONC.

Shown is an eye imaginal disc from a third instar larva. Posterior is to the right. diap1-overexpressing clones are marked by absence of GFP and can be detected using anti-DIAP1 antibodies in magenta (A′″). The boundary between diap1-expressing clones and normal tissue is indicated by a white stippled line in (A′). DRONC levels are unchanged (A′). (A) and (A″) are merged images. Genotype: UAS-diap1/hs-FLP; tub>GFP>GAL4.

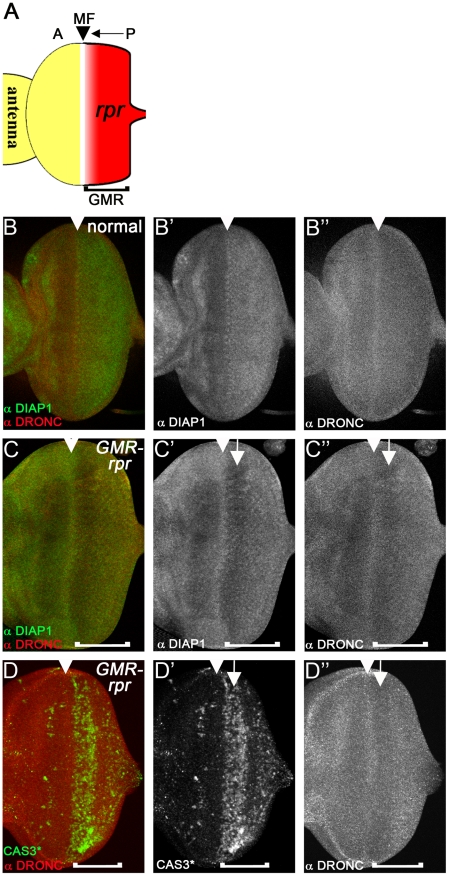

REAPER-induced loss of DIAP1 does not increase DRONC protein levels

Because of the surprising observation that overexpressed DIAP1 does not cause degradation of DRONC, we tested whether removal of DIAP1 changes DRONC protein levels. Expression of the IAP antagonist reaper (rpr) induces DIAP1 degradation and apoptosis [54]–[58]. Therefore, we examined whether RPR-induced degradation of DIAP1 changes DRONC protein levels. If DIAP1 targets DRONC for degradation, we would expect that DRONC protein levels would accumulate in response to rpr expression. Expression of rpr in eye imaginal discs posterior to the morphogenetic furrow (MF) using the GMR promoter (GMR-rpr) is well suited for this analysis. The MF is a dynamic structure that initiates at the posterior edge of the eye disc and moves towards the anterior during 3rd instar larval stage [59], [60] (Figure 4A, arrow). Expression of rpr by GMR is induced in all cells posterior to the MF [61] (red in Figure 4A). Therefore, GMR-rpr eye discs provide a continuum of all developmental stages in which cells close to the MF have only recently induced rpr expression, while cells towards the posterior edge of the disc have been exposed to rpr progressively longer. Therefore, if DRONC accumulates during any of these stages, we should be able to detect it. In wild-type eye discs, DRONC protein is homogenously distributed throughout the disc. Only in the MF, higher levels of DRONC are detectable (arrowhead in Figure 4B″). This high expression of DRONC in the MF serves as an orientation mark. DIAP1 protein levels are low anterior to the MF, but increase in the MF (arrowhead) and posterior to it in wild-type discs (Figure 4B′). In GMR-rpr eye discs, overall DIAP1 levels are reduced in the rpr-expressing domain posterior to the MF (Figure 4C′), but particularly strongly reduced in the CAS3*-positive area (Figure 4C′, D′, arrow) consistent with previous reports [54]–[58]. However, accumulation of DRONC is not observed (Figure 4C″, D″). In contrast, it appears that DRONC levels are also reduced. They are still high in the MF (Figure 4C″, arrowhead), but drop immediately thereafter.

Figure 4. Loss of DIAP1 in GMR-rpr eye discs does not alter DRONC protein levels.

(A) Schematic illustration of the GMR-reaper (GMR-rpr) eye imaginal disc from 3rd instar larvae. The morphogenetic furrow (MF, arrowhead) initiates at the posterior (P) edge of the disc and moves towards the anterior (A) (arrow). The GMR enhancer is active posterior to the MF (bracket) and thus expresses rpr posterior to the MF (red area). (B-B″) Eye disc showing normal protein distribution of DIAP1 (B′) and DRONC (B″). Both DIAP1 and DRONC levels are increased in the MF (arrowhead). (B) is the merged image of DIAP1 and DRONC labeling. (C–C″) Eye discs expressing two copies of GMR-rpr eye disc labeled for DIAP1 (C′) and DRONC (C″). Arrowheads mark the MF. DIAP1 levels are markedly reduced posterior to the MF (C′, arrow). Surprisingly, DRONC protein levels are also reduced (C″, arrow). The brackets indicate the extent of GMR expression. (D–D″) 2×GMR-rpr eye disc labeled for cleaved CASPASE 3 (CAS3*) (D′) and DRONC (D″). DRONC protein levels are reduced in the CAS3*-positive area (arrow). Arrowheads mark the MF. The brackets indicate the extent of GMR expression.

We also related DRONC levels to caspase activation. In the MF, where CAS3* activity is not detectable, DRONC is still high (Figure 4D′, D″; arrowhead), but in the CAS3*-positive area, DRONC levels are reduced (Figure 4D′, D″; arrow). These data indicate that loss of DIAP1 does not cause accumulation of DRONC protein implying that DIAP1 does not induce degradation of DRONC. In contrast, it appears that DIAP1 stabilizes DRONC at least under these conditions (see Discussion).

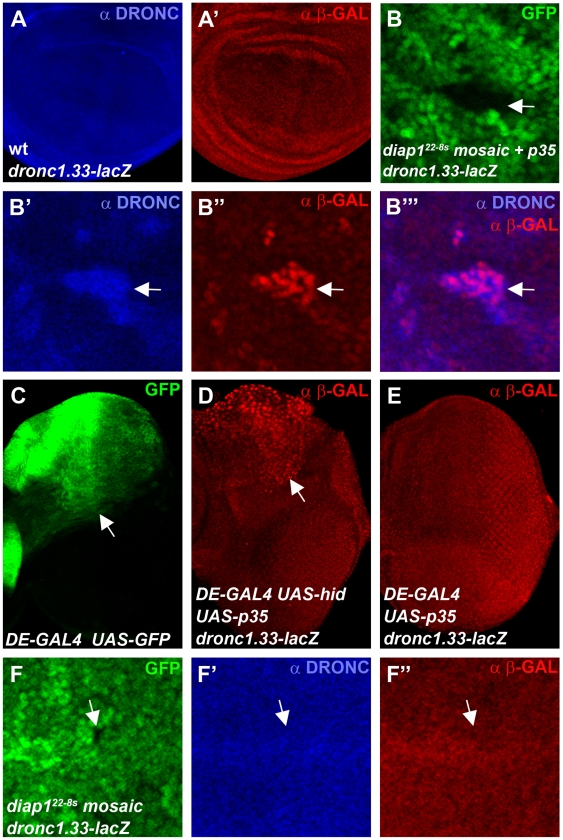

“Undead” diap1 mutant cells induce transcription of dronc

Finally, we analyzed DRONC protein levels in diap1ΔRING mutants which cannot ubiquitylate DRONC [44]. It has previously been shown that clones of the RING mutant diap122 -8s accumulate DRONC protein [45], [46] implying that ubiquitylation by the RING domain of DIAP1 causes degradation of DRONC. We repeated these experiments and indeed confirmed that DRONC levels are increased in diap122 -8s mutant clones (Figure S4). Thus, these results appear inconsistent with the data presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4 in which manipulating DIAP1 levels did not provide evidence for DIAP1-mediated degradataion of DRONC. However, one caveat with the diap122 -8s experiment was the use of the caspase inhibitor P35 which kept diap122 -8s mutant cells in an ‘undead’ condition [45]. It has been pointed out that the ‘undead’ state may change the properties of the affected cells (reviewed by [62]) and in fact abnormal induction of transcription in ‘undead’ cells has been reported [45], [63]–[66]. Thus, to explain the conflicting results between the diap122 -8s data [45] and our data shown here, we hypothesized that p35-expressing ‘undead’ diap122 -8s clones induce dronc transcription, leading to accumulation of DRONC protein. To test this hypothesis, we used a transcriptional lacZ reporter containing 1.33 kb of regulatory genomic sequences upstream of the transcriptional start site of the dronc gene fused to lacZ (dronc1.33-lacZ) [67], [68]. Compared to controls (Figure 5A, 5A′) and consistent with the hypothesis, dronc1.33-lacZ reporter activity is increased in p35-expressing ‘undead’ diap122 -8s cells in wing imaginal discs and matches the increased DRONC protein pattern (Figure 5B′-5B′″). We also produced ‘undead’ cells in eye imaginal discs by co-expression of the IAP-antagonist hid and the caspase inhibitor p35 in the dorsal half of the eye disc using a dorsal eye- (DE-) GAL4 driver (Figure 5C). Similar to wing discs, dronc reporter activity is increased in ‘undead’ cells in the dorsal half of the eye (Figure 5D). Expression of p35 alone does not trigger transcription of dronc (Figure 5E) suggesting it is not the mere presence of P35 which causes dronc transcription, but the ‘undead’ nature of the affected cells.

Figure 5. “Undead” diap1 mutant cells trigger transcription of dronc.

Shown are 3rd instar larval wing (A,B,F) and eye imaginal discs (C,D,E) labeled for DRONC protein levels (blue) and dronc transcriptional activity (red) using the dronc1.33-lacZ reporter (ß-GAL labeling). (A,A′) Co-labeling for DRONC protein (A) and dronc reporter activity (A′) of a wild-type wing disc expressing the dronc1.33-lacZ transgene. (B-B′″) A diap122-8s mosaic wing disc expressing p35 under nub-GAL4 control in a dronc1.33-lacZ background. A mutant clone in the wing pouch is highlighted by an arrow in the GFP-only channel (B). DRONC protein (B′) and ß-GAL immunoreactivity as readout of dronc1.33-lacZ activity (B″) are increased in the same cells and overlap (B′″). Please note that the dronc1.33-lacZ reporter produces nuclear ß-GAL, while DRONC protein appears cytoplasmic. (C) GFP expression in the eye imaginal disc indicates the dorsal expression domain (arrow) of the dorsal eye (DE)-GAL4 driver [95]. (D) Increased dronc reporter activity in the dorsal half of the eye imaginal disc (arrow) in undead cells obtained by co-expression of hid and p35 using DE-GAL4. (E) Expression of p35 alone by DE-GAL4 does not induce dronc reporter activity. (F-F″) A diap122-8s mosaic wing disc in a dronc1.33-lacZ background which does not express p35. diap122-8s mutant clones are marked by the absence of GFP (F). An arrow points to a representative diap122-8s clone in the wing pouch. In the same position, neither DRONC protein (F′) nor dronc reporter activity (F″) are increased. Note, that this clone is present in the wing pouch which has the capacity to upregulate DRONC and dronc transcription in the ‘undead’, p35-expressing condition (see panel B″). Genotypes: (A) dronc1.33-lacZ/+. (B) ubx-FLP; nub-GAL4 UAS-p35/dronc1.33-lacZ; diap122-8s FRT80/ubi-GFP FRT80. (C) DE-GAL4 UAS-GFP/+. (D) UAS-p35 UAS-hid/dronc1.33-lacZ; DE-GAL4. (E) UAS-p35/dronc1.33-lacZ; DE-GAL4. (F) ubx-FLP; nub-GAL4/dronc1.33-lacZ; diap122-8s FRT80/ubi-GFP FRT80.

These observations may explain why DRONC protein accumulates in ‘undead’ diap122 -8s mutant cells, but they still do not rule out the possibility that DRONC protein accumulates in diap122 -8s mutants due to lack of ubiquitylation and thus degradation. To clarify this issue we examined dronc1.33-lacZ and DRONC levels in diap122 -8s mutant clones without simultaneous p35 expression. Without the inhibition of apoptosis by P35, diap122 -8s clones die rapidly. Nevertheless, we were able to recover wing discs which contained small diap122-8s mutant clones. In these clones, neither dronc1.33-lacZ nor DRONC levels are detectably increased (Figure 5F). Notably, these clones are located in the wing pouch in which we observed accumulation of dronc reporter activity and DRONC protein under ‘undead’ conditions (Figure 5B″). Thus, the ‘undead’ condition of p35-expressing diap122 -8s mutant cells causes accumulation of DRONC protein due to induction of dronc transcription, explaining the observations of Ryoo et al. (2004) [45]. In the absence of p35 expression, transcription of dronc and accumulation of DRONC protein are not observed, providing additional evidence that ubiquitylation of DRONC by the RING domain of DIAP1 does not trigger degradation of DRONC.

Ubiquitylation controls processing and thus activation of DRONC in vivo

Our in vivo analysis implies that DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation does not trigger proteasomal degradation of DRONC. To identify the role of ubiquitylation for regulation of DRONC activity, we analyzed the fate of DRONC protein in RING mutants of diap1. Of note, these mutants retain their ability to bind to DRONC, because DRONC binding is not mediated by the RING domain, but by the BIR2 domain [37], [38], [43]. The RING mutant diap133-1s is especially suitable for this analysis because a premature stop codon results in deletion of the entire RING domain but leaves the BIR domains intact [44] (Figure 6A), thus abrogating its E3 activity, but not caspase binding. Importantly, diap133-1s is characterized by a strong apoptotic phenotype, suggesting inappropriate caspase activation [41], [45]. Indeed, we showed previously that diap1ΔRING mutant phenotypes are dependent upon DRONC, because dronc mutants suppress diap1ΔRING phenotypes [11]. Therefore, ubiquitylation of DRONC by DIAP1 is critical to maintain cell survival.

Figure 6. Ubiquitylation controls processing of DRONC.

(A) Top: schematic outline of the domain structure of DIAP1+ (wild-type) and RING-deleted DIAP133-1s. Not drawn to scale. Immunoblots of embryonic extracts of stage 6–9 wild-type (wt) and heterozygous diap133-1s mutants were probed with anti-DIAP1 (upper panel) and anti-DRONC antibodies (middle panel). The RING-depleted diap133-1s allele produces a stable protein (DIAP133-1s) that is detectable by its faster electrophoretic mobility (upper panel). In RING-depleted diap133-1s embryos a significant portion of processed DRONC is present (middle panel) which likely accounts for the apoptotic phenotype of diap133-1s embryos [41]. These extracts were obtained from a cross of heterozygous males and females. Thus, only one quarter of the embryos is homozygous mutant for diap133-1s; yet, processed DRONC is easily detectable. The anti-DRONC antibody is specific for the large subunit of DRONC. Lower panel: loading control. (B) Extracts of imaginal discs from wild-type (wt) and mosaic Uba1 imaginal discs were analyzed by immunoblotting using an antibody raised against the small subunit of DRONC. Clones of the temperature sensitive allele Uba1D6 were induced at the permissive temperature in first larval instar and then shifted to the non-permissive temperature (30°C) during third larval instar 12 hours before dissection (see Material and Methods). This treatment ensures that approximately 50% of the mosaic disc is mutant for Uba1. Although only 50% of the disc tissue is mutant for Uba1, processed DRONC is easily detectable. Lower panel: loading control.

We examined the cause of the diap133 -1s apoptotic phenotype. First, as a control, we determined whether the diap133 -1s gene produces a stable protein in vivo. We chose to analyze stage 6–9 embryos, because normal developmental cell death starts at stage 11 [69]; therefore, stage 6–9 diap133 -1s mutant embryos allow analysis of DIAP1 in the absence of upstream apoptotic signals. In immunoblots of embryonic extracts obtained from a cross of heterozygous diap133 -1s males and females, the DIAP133-1s protein is easily distinguished from wild-type DIAP1+ protein due to its faster electrophoretic mobility (Figure 6A, top panel). The presence of the DIAP133-1s protein suggests that the apoptotic phenotype in diap133 -1s mutant embryos is not caused by instability of the mutant protein. Interestingly, the protein levels of DIAP1+ and RING-deleted DIAP133-1s are similar (Figure 6A, top panel) suggesting that loss of the RING domain does not influence the protein stability of DIAP1 in the absence of pro-apoptotic signals.

Next, we analyzed DRONC protein in extracts from diap133 -1s mutant embryos. Consistent with the data in Figure 4 and Figure 5, we do not detect a significant increase in the protein levels of DRONC in these embryos (Figure 6A, middle panel). However, a significant amount of DRONC is present in a processed form in extracts of stage 6–9 diap133-1s mutant embryos which is absent in control extracts from wild-type embryos (Figure 6A, middle panel). Therefore, DRONC processing, and thus activation, occurs in RING-depleted diap133 -1s mutant embryos despite the fact that the BIR domains of DIAP1 are unaffected. The processed form of DRONC in this mutant of MW ∼36 kDa corresponds to the major apoptotic form of DRONC composed of the large subunit and the prodomain of DRONC [70]. This finding, and the one presented in Figure 1, confirms that binding of DIAP1 to DRONC is not sufficient to prevent processing and activation of DRONC. Instead, the RING domain is required to control DRONC processing. Because the RING domain contains an E3-ubiquitin ligase activity [45], [55]–[58] and because ubiquitylation of full-length DRONC does not trigger proteasomal degradation (Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5), we conclude that ubiquitylation of DRONC by the RING domain of DIAP1 is necessary to inhibit DRONC processing and thus activation.

To further characterize the role of ubiquitylation in the regulation of DRONC processing, we performed an immunoblot analysis with extracts from wild-type and Uba1 mosaic imaginal discs, which, under our experimental conditions, are about half mutant for Uba1 and half wild-type. Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that a significant amount of DRONC is processed in Uba1 mosaic discs (Figure 6B). Thus, these data further support the notion that ubiquitylation of full-length DRONC is necessary for inhibition of DRONC processing.

Discussion

In this paper, we provide three take-home messages. First, we provide genetic evidence that binding of DIAP1 to DRONC is not sufficient for inhibition of DRONC. Instead, ubiquitylation of DRONC controls its apoptotic activity, consistent with the apoptotic phenotype of diap1ΔRING mutants, that retain caspase binding abilities. Second, DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation of full-length DRONC does not lead to its proteasomal degradation; rather, ubiquitylation directly controls processing and activation of DRONC. Interestingly, processed and active DRONC shows reduced protein stability. Third, ‘undead’ cells accumulate dronc transcripts.

Binding of DIAP1 is not sufficient for Dronc inhibition

Based on biochemical studies in vitro and overexpression studies in cultured cells, many of cancerous origin, it was initially proposed that binding of IAPs to caspases through their BIR domains is sufficient to inhibit caspases [71]–[80]. However, when ubiquitylation of caspases by IAPs was described [38], [44], [47], [48], it was unclear what role ubiquitylation would play for control of caspase activity, especially since for none of them, ubiquitin-mediated degradation has been observed (see below). Because the RING domain is also required for auto-ubiquitylation of DIAP1 [54]–[58], mutations of the RING domain would be expected to increase DIAP1 protein levels and protect cells from apoptosis. However, the opposite phenotype, massive apoptosis, was observed [41]. Nevertheless, despite the biochemical studies showing that the BIR domains of DIAP1 are sufficient for interaction with DRONC [37], [38], [43], one could argue that DIAP1ΔRING mutants have lost the ability to interact with DRONC in vivo. While we cannot exclude this possibility due to the inability of our antibodies to immunoprecipitate endogenous proteins, another experiment supports the notion that ubiquitylation is necessary for DRONC inhibition: when wild-type diap1 was strongly overexpressed in an ubiquitylation-deficient Uba1 mutant background, DRONC-dependent apoptosis was not inhibited (Figure 1C), suggesting that binding of DIAP1 is not sufficient for inhibition of DRONC. Instead, ubiquitylation is critical for inhibition of DRONC activity.

DIAP1 does not control protein levels of full-length DRONC

The current model holds that DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation leads to proteasomal degradation of full-length DRONC in living cells [33], [38], [45]. However, our data do not support this model in vivo. This model is based on biochemical ubiquitylation studies without in vivo validation and does not take into account that ubiquitylation often serves non-proteolytic functions [1], [3], [4]. Both overexpression and loss of diap1 does not cause a detectable alteration of the protein levels of DRONC (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5), arguing against a degradation model. The only example where DRONC accumulation has been observed is in P35-expressing ‘undead’ diap1ΔRING mutant cells [45], [46], and we showed here that the ‘undead’ nature of these cells causes transcriptional induction of dronc (Figure 5). Together, these observations argue against a degradation model of full-length DRONC and favor a non-traditional (non-proteolytic) role of ubiquitylation regarding control of DRONC activity. Similarly, DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation of the effector caspase DrICE inactivates this effector caspase through a non-degradative mechanism [50].

Interestingly, in GMR-rpr eye imaginal discs, DRONC protein levels appear to be reduced in apoptotic cells compared to living cells (Figure 4C″, 4D″). Due to the apoptotic activity of REAPER, DRONC is present in its processed and activated form. Reduced protein stability of DRONC has also been reported after incorporation into the ARK apoptosome where it is processed and activated [46]. Combined, these observations suggest that while DIAP1-mediated ubiquitylation of full-length DRONC does not trigger its degradation, processed and activated DRONC has reduced protein stability and may indeed be degraded. It is unclear whether degradation of activated DRONC is mediated by DIAP1, as proposed previously [33]. In GMR-rpr eye imaginal discs, reduced DRONC levels correlate with a reduction of DIAP1 protein (Figure 4C′, 4D′). This correlation indicates that DIAP1 may actually stabilize DRONC protein, at least in part. Alternatively, because DRONC and DIAP1 form a complex [37], REAPER-induced degradation of DIAP1 may result in co-degradation of complexed DRONC in the process. Further studies are needed to determine the cause of decreased DRONC stability in apoptotic cells.

In addition to Drosophila DRONC, mammalian CASPASE-3 and CASPASE-7 have been reported to be ubiquitylated in vitro [47], [48]. However, proteasome-mediated degradation of these caspases in vivo has not been reported. Although a decrease of CASPASE-3 levels has been noted upon overexpression of XIAP, this was shown for an artificial CASPASE-3 mutant, in which the order of the subunits was reversed and the Cys residue in the active site changed to Ser [47]. This catalytically inactive CASPASE-3 mutant is not proteolytically processed [47]. Therefore, physiological in vivo evidence for IAP-mediated degradation of mammalian caspases is lacking.

Moreover, the phenotype of a RING-deleted XIAP mutant mouse is consistent with our data [49]. The XIAPΔRING mutant, which was generated by a knock-in approach in the endogenous XIAP gene, is characterized by increased caspase activity [49]. Intriguingly, the protein levels of CASPASE-3, CASPASE-7 and CASPASE-9 did not significantly change in the XIAPΔRING mutant despite the fact that ubiquitylation of CASPASE-3 was reduced. However, processing of these caspases was easily detectable in XIAPΔRING mutants [49]. These data are very similar to the ones presented here for diap133 -1s (Figure 6), and together strongly suggest that non-proteolytic ubiquitylation controls caspase processing and activity in both vertebrates and invertebrates.

Non-proteolytic roles of ubiquitylation have been described in recent years and are involved in many processes including signal transduction, endocytosis, DNA repair, and histone activity (reviewed in [1], [3], [4]). Two types of ubiquitylation lead to non-proteolytic functions. Monoubiquitylation is involved in endocytosis, DNA repair and histone activity. In fact, mammalian CASPASE-3 and CASPASE-7 have been found to be monoubiquitylated in vitro [48]. However, it is unclear whether DRONC is monoubiquitylated by DIAP1. The presence of high molecular-weight ubiquitin conjugates in vitro (Figure 2) suggests that DRONC may be polyubiquitylated, at least under the experimental conditions [38], [44].

Polyubiquitylation serves both proteolytic and non-proteolytic functions depending on the Lysine (K) residue used for polyubiquitin chain formation. In general, if polyubiquitylation occurs via K48, the target protein is subject to proteasome-mediated degradation. If it occurs on a different Lys residue, such as K63, non-proteolytic functions are induced [1], [3], [4]. The best studied examples of both K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitylation are in the NF-κB pathway (reviewed in [3], [81]). While K48-polyubiquitylation leads to proteasomal degradation, K63-linked polyubiquitin chains act as scaffolds to assemble protein complexes required for NF-κB activation [3], [81]. It is unknown what type of polyubiquitin chain is attached to DRONC, but it is possible that it is not K48-linked. Interestingly, in this context it has been shown that auto-ubiquitylation of DIAP1 preferentially involves K63-linked polyubiquitin chains [82]. By analogy, DIAP1 may ubiquitylate DRONC through formation of K63-linked polyubiquitin chains. This will be an interesting avenue to explore in future experiments.

Conjugated monoubiquitin and polyubiquitin chains can serve as docking sites for factors containing ubiquitin-binding domains (UBD) [2], [4], [83]. The UBD-containing factors interpret the ubiquitylation status of the target protein, and trigger the appropriate response. For example, K48-linked polyubiquitin chains are recognized by Rad23 and Drk2 which deliver them to the proteasome [2]. Other forms of ubiquitin conjugates are recognized by different UBD-containing factors which control the activity of the ubiquitylated protein. Therefore, it is possible that an as yet unknown UBD-containing protein binds to ubiquitylated DRONC and controls its activity. For example, such an interaction could block the recruitment of ubiquitylated DRONC into the ARK apoptosome. Another possibility is that ubiquitylation could block dimerization of DRONC, which is required for activation of DRONC [34].

“Undead” cells trigger dronc transcription

‘Undead’ cells can be obtained by expression of the effector caspase inhibitor P35 [84]. In these cells, apoptosis has been induced, but cannot be executed due to effector caspase inhibition. Nevertheless, the initiator caspase DRONC is active in ‘undead’ cells and can promote non-apoptotic processes [51]. Recent work has suggested that ‘undead’ cells may alter their cellular behavior. For example, ‘undead’ cells change their size and shape, and have some migratory abilities to invade neighboring tissue [62]. They are also able to promote proliferation of neighboring cells causing hyperplastic overgrowth [15], [45], [63]–[66] (reviewed by [85], [86]). Altered transcription of the TGF-ß/BMP member decapentaplegic (dpp), the Wnt-homolog wingless (wg), and the p53 ortholog dp53 has also been reported in ‘undead’ cells [45], [64]–[66]. Intriguingly, while dpp and wg are usually not expressed in the same cells [87], ‘undead’ cells co-express them ectopically, clearly indicating an altered transcriptional program.

As part of this altered transcriptional program, we showed that ‘undead’ cells also stimulate transcription of the initiator caspase dronc (Figure 5). Interestingly, p35 expression in normal cells does not induce dronc transcription suggesting that it is not the mere presence of P35 that induces dronc transcription, but instead the ‘undead’ condition of the affected cells. This transcriptional induction of dronc provides an explanation why DRONC protein levels are increased in ‘undead’ cells. It may also help to explain another observation regarding ‘undead’ cells. It has been demonstrated that although these cells are unable to die, they maintain the apoptotic machinery indefinitely [62], [88]. Therefore, as part of this maintenance program, ‘undead’ cells stimulate dronc transcription. This is likely not restricted for dronc. Martin et al. (2009) [62] also showed that DrICE protein levels remain high in ‘undead’ cells which may also be caused by increased drICE transcription. It is also possible that the induction of dp53 by ‘undead’ cells [66] is part of this maintenance program, because we have shown that Dp53 induces expression of hid and rpr [89] and a positive feedback loop between dp53, hid and dronc exists in ‘undead’ cells [66]. This may all occur at a transcriptional level. The mechanism by which ‘undead’ cells stimulate expression of dpp, wg, dp53, dronc and potentially drICE are currently unknown and are avenues for future research.

Material and Methods

Drosophila genetics

Fly crosses were conducted using standard procedures at 25°C. The following mutants and transgenes were used: Uba1D6 [5]; arkG8 [26]; diap122-8s and diap133 -1s [44]; vps25N55 [90]; droncI29 [11]; UAS-droncIR (dronc inverted repeats) [91]; GMR-rpr [92]; dronc1.33-lacZ [67], [68], ubx-FLP [93], nub-GAL4 [94], DE- (dorsal eye-) GAL4 [95], and UAS-hid [96]. nub-FLP is nub-GAL4 UAS-FLP. UAS-p35 and UAS-FLP were obtained from Bloomington. Uba1D6 is a temperature sensitive allele which at 25°C is a hypomorphic allele, but at 30°C is a null allele [5]. In the experiments in Figure 1, Figure 6B, and Figure S1, Uba1D6 and Uba1D6 arkG8 mosaic larvae were incubated at 25°C; 12 hours before dissection the temperature was shifted to 30°C. This treatment allows recovery of Uba1D6 null mutant clones, which otherwise are cell lethal.

Generation of mutant clones and expression of transgenes

Mutant clones were induced in eye-antennal imaginal discs using the FLP/FRT mitotic recombination system [97] using ey-FLP [98]. In this case, clones are marked by loss of GFP. Expression of diap1 and dronc RNAi in Uba1D6 clones (Figure 1) was induced from UAS-diap1 or UAS-droncIR transgenes using the MARCM system [99]. Here, clones are positively marked by GFP. For induction of diap1-expressing clones in Figure 3, the UAS-diap1 transgene was crossed to hs-FLP; tub<GFP<GAL4 (< = FRT). Clones are marked by the absence of GFP. MARCM clones and diap1-overexpressing clones were induced in first instar larvae by heat-shock for one hour in a 37°C water bath. Expression of UAS-p35 in diap122-8s mosaic discs was accomplished by nub-GAL4.

Immunohistochemistry

Eye-antennal imaginal discs from third instar larvae were dissected using standard protocols and labeled with antibodies raised against the following antigens: DIAP1 (a kind gift of Hermann Steller and Hyung Don Ryoo); cleaved CASPASE-3 (CAS3*) (Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-ß-GAL (Promega). The DRONC antibody used for immunofluorescence was raised against the C-terminus of DRONC in guinea pigs [44]. This antibody is specific for DRONC (Figure S3). Cy3- and Cy-5 fluorescently-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch. In each experiment, multiple clones in 10–20 eye and wing imaginal discs were analyzed, unless otherwise noted. Images were captured using an Olympus Optical FV500 confocal microscope.

Ubiquitylation assays

Schneider S2 cells were co-transfected with pMT-DRONC C>A V5, pAcDIAP1 (wt or CΔ6, F437A, respectively, described in [50]) and pAc His-HA-Ub at equal ratios. Expression of DRONC was induced overnight with 350 µM CuSO4. Cells were lysed under denaturing conditions and ubiquitylated proteins were purified using Ni2+-NTA agarose beads (QIAGEN). Immunoblot analysis was performed with α-V5 (Serotec) and α-DIAP1 antibodies [37], [43].

Immunoblot analysis

For the immunoblots in Figure 6A, embryos were collected, decorionated and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Embryos were sonicated in Laemmli SDS loading buffer while being frozen. The equivalent of 30 lysed embryos was loaded per lane. Immunoblots were done using standard procedures. The anti-DRONC antibody used in Figure 6A is a peptide antibody raised against the large subunit of DRONC. The anti-DRONC antibody used in Figure 6B was raised against the C-terminus of DRONC in guinea pigs.

Supporting Information

Loss of ark suppresses apoptosis in Uba1 clones. Uba1 ark mosaic eye-antennal disc labeled for cleaved CASPASE-3 (CAS3*) antibody (red). These discs were incubated at 30°C 12 hours before dissection (see Material and Methods). Absence of GFP marks the location of Uba1 ark clones (see arrows). There is scattered apoptosis detectable. However, this occurs throughout the disc and does not correlate with the positions of the Uba1 ark double mutant clones. Genotype: ey-FLP; FRT42D Uba1D6 arkG8/FRT42D ubi-GFP.

(TIF)

UAS-diap1 rescues GMR-hid and apoptosis induced in vps25 mutants. Because the UAS-diap1 transgene failed to suppress apoptosis in Uba1 clones (Figure 1C), we tested its ability to inhibit the strong apoptotic phenotype in two other paradigms. (A) Overexpression of the IAP-antagonist hid specifically in the fly eye under GMR promoter control gives rise to a strong eye ablation phenotype due to massive induction of apoptosis [100]. (B) Coexpression of UAS-diap1 partially suppresses the GMR-hid eye ablation phenotype [42]. (C) vps25 mutant clones induce a strong apoptotic phenotype. vps25 encodes an component involved in endosomal protein sorting [90]. The apoptotic phenotype of vps25 and Uba1 as well as other phenotypes caused by inactivation of these genes are very similar, and both mutants were obtained in the same genetic screen [5], [90]. The left panel is the merge of GFP and anti-cleaved CASPASE-3 (CAS3*) labeling, the right panel (C′) displays only the CAS3* channel. White arrows mark a few clones as examples. (D) Overexpression of diap1 completely suppresses the strong apoptotic phenotype of vps25 mutant clones. The experimental conditions applied here are identical to the Uba1 experiment in Figure 1C. The left panel is the merge of GFP and anti-cleaved CASPASE-3 (CAS3*) labeling, the right panel (D′) displays only the CAS3* channel. Genotype: hs-FLP UAS-GFP/UAS-diap1; FRT42D vps25N55/FRT42D tub-Gal80; tub-GAL4. Genotypes: (A) GMR-hid GMR-GAL4. (B) UAS-diap1; GMR-hid GMR-GAL4. (C) ey-FLP; FRT42D vps25N55/FRT42D P[ubi-GFP]. (D) ey-FLP; FRT42D vps25N55/FRT42D P[ubi-GFP].

(TIF)

Specificity of the anti-DRONC antibody. The specificity of the anti-DRONC antibody used for immunofluorescence in Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5 was verified in droncI29 mosaic eye (A) and wing (B) imaginal discs. The droncI29 allele contains a premature STOP codon at position 53 [11]. droncI29 clones were induced using the MARCM system, hence they are positively marked by GFP (arrows). The anti-DRONC antibody does not produce labeling signals in the mutant clones (arrows in A′ and B′, and the merge in A″ and B″), demonstrating that it is specific for DRONC. Genotype: hs-FLP; droncI29 FRT80/ubi-GFP FRT80.

(TIF)

“Undead” diap122-8s cells accumulate DRONC protein autonomously. (A, A′) Using MARCM, p35-expressing, ‘undead’ diap122-8s mutant clones (green) were induced in eye discs and labeled for DRONC protein (red). DRONC protein autonomously accumulates in P35-expressing diap122-8s clones (arrows). Similar results were obtained in wing discs (data not shown). Genotype: hs-FLP tub-GAL4 UAS-GFP/+; UAS-p35/+; diap122-8s FRT80/tub-GAL80 FRT80.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Hans-Martin Herz for the vps25 data in Figure S2; Audrey Christiansen for the outline of eye imaginal discs in Figure 4A; Hugo Bellen, Georg Halder, Sharad Kumar, Hyung Don Ryoo, Hermann Steller, and Kristin White for antibodies and fly stocks; and the Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

This work is supported by NIH grants (R01s GM068016, GM081543) and by an anonymous donor to AB. MB is supported by a fellowship of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Welchman RL, Gordon C, Mayer RJ. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins as multifunctional signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:599–609. doi: 10.1038/nrm1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hicke L, Schubert HL, Hill CP. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:610–621. doi: 10.1038/nrm1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen ZJ, Sun LJ. Nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitin in cell signaling. Mol Cell. 2009;33:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukhopadhyay D, Riezman H. Proteasome-independent functions of ubiquitin in endocytosis and signaling. Science. 2007;315:201–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1127085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee TV, Ding T, Chen Z, Rajendran V, Scherr H, et al. The E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme Uba1 in Drosophila controls apoptosis autonomously and tissue growth non-autonomously. Development. 2008;135:43–52. doi: 10.1242/dev.011288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Degterev A, Yuan J. Expansion and evolution of cell death programmes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:378–390. doi: 10.1038/nrm2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar S. Caspase function in programmed cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:32–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bao Q, Shi Y. Apoptosome: a platform for the activation of initiator caspases. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:56–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riedl SJ, Salvesen GS. The apoptosome: signalling platform of cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:405–413. doi: 10.1038/nrm2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Timmer JC, Salvesen GS. Caspase substrates. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:66–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu D, Li Y, Arcaro M, Lackey M, Bergmann A. The CARD-carrying caspase Dronc is essential for most, but not all, developmental cell death in Drosophila. Development. 2005;132:2125–2134. doi: 10.1242/dev.01790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu D, Wang Y, Willecke R, Chen Z, Ding T, et al. The effector caspases drICE and dcp-1 have partially overlapping functions in the apoptotic pathway in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1697–1706. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chew SK, Akdemir F, Chen P, Lu WJ, Mills K, et al. The apical caspase dronc governs programmed and unprogrammed cell death in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2004;7:897–907. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daish TJ, Mills K, Kumar S. Drosophila caspase DRONC is required for specific developmental cell death pathways and stress-induced apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2004;7:909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kondo S, Senoo-Matsuda N, Hiromi Y, Miura M. DRONC coordinates cell death and compensatory proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7258–7268. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00183-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waldhuber M, Emoto K, Petritsch C. The Drosophila caspase DRONC is required for metamorphosis and cell death in response to irradiation and developmental signals. Mech Dev. 2005;122:914–927. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilpatrick ZE, Cakouros D, Kumar S. Ecdysone-mediated up-regulation of the effector caspase DRICE is required for hormone-dependent apoptosis in Drosophila cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11981–11986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muro I, Berry DL, Huh JR, Chen CH, Huang H, et al. The Drosophila caspase Ice is important for many apoptotic cell deaths and for spermatid individualization, a nonapoptotic process. Development. 2006;133:3305–3315. doi: 10.1242/dev.02495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorstyn L, Colussi PA, Quinn LM, Richardson H, Kumar S. DRONC, an ecdysone-inducible Drosophila caspase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4307–4312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanuka H, Sawamoto K, Inohara N, Matsuno K, Okano H, et al. Control of the cell death pathway by Dapaf-1, a Drosophila Apaf-1/CED-4-related caspase activator. Mol Cell. 1999;4:757–769. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80386-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez A, Oliver H, Zou H, Chen P, Wang X, et al. Dark is a Drosophila homologue of Apaf-1/CED-4 and functions in an evolutionarily conserved death pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:272–279. doi: 10.1038/12984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou L, Song Z, Tittel J, Steller H. HAC-1, a Drosophila homolog of APAF-1 and CED-4 functions in developmental and radiation-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell. 1999;4:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quinn LM, Dorstyn L, Mills K, Colussi PA, Chen P, et al. An essential role for the caspase dronc in developmentally programmed cell death in Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40416–40424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorstyn L, Read S, Cakouros D, Huh JR, Hay BA, et al. The role of cytochrome c in caspase activation in Drosophila melanogaster cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:1089–1098. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dorstyn L, Kumar S. A biochemical analysis of the activation of the Drosophila caspase DRONC. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:461–470. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Srivastava M, Scherr H, Lackey M, Xu D, Chen Z, et al. ARK, the Apaf-1 related killer in Drosophila, requires diverse domains for its apoptotic activity. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:92–102. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mills K, Daish T, Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, Hariharan IK, et al. The Drosophila melanogaster Apaf-1 homologue ARK is required for most, but not all, programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:809–815. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akdemir F, Farkas R, Chen P, Juhasz G, Medved'ova L, et al. Autophagy occurs upstream or parallel to the apoptosome during histolytic cell death. Development. 2006;133:1457–1465. doi: 10.1242/dev.02332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendes CS, Arama E, Brown S, Scherr H, Srivastava M, et al. Cytochrome c–d regulates developmental apoptosis in the Drosophila retina. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:933–939. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu X, Wang L, Acehan D, Wang X, Akey CW. Three-dimensional structure of a double apoptosome formed by the Drosophila Apaf-1 related killer. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:577–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan S, Yu X, Topf M, Dorstyn L, Kumar S, et al. Structure of the Drosophila apoptosome at 6.9 a resolution. Structure. 2011;19:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hawkins CJ, Yoo SJ, Peterson EP, Wang SL, Vernooy SY, et al. The Drosophila caspase DRONC cleaves following glutamate or aspartate and is regulated by DIAP1, HID, and GRIM. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27084–27093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muro I, Hay BA, Clem RJ. The Drosophila DIAP1 protein is required to prevent accumulation of a continuously generated, processed form of the apical caspase DRONC. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49644–49650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snipas SJ, Drag M, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS. Activation mechanism and substrate specificity of the Drosophila initiator caspase DRONC. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:938–945. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Riordan MX, Bauler LD, Scott FL, Duckett CS. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in eukaryotic evolution and development: a model of thematic conservation. Dev Cell. 2008;15:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaux DL, Silke J. IAPs, RINGs and ubiquitylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:287–297. doi: 10.1038/nrm1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meier P, Silke J, Leevers SJ, Evan GI. The Drosophila caspase DRONC is regulated by DIAP1. Embo J. 2000;19:598–611. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chai J, Yan N, Huh JR, Wu JW, Li W, et al. Molecular mechanism of Reaper-Grim-Hid-mediated suppression of DIAP1-dependent Dronc ubiquitination. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:892–898. doi: 10.1038/nsb989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang SL, Hawkins CJ, Yoo SJ, Muller HA, Hay BA. The Drosophila caspase inhibitor DIAP1 is essential for cell survival and is negatively regulated by HID. Cell. 1999;98:453–463. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81974-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goyal L, McCall K, Agapite J, Hartwieg E, Steller H. Induction of apoptosis by Drosophila reaper, hid and grim through inhibition of IAP function. EMBO J. 2000;19:589–597. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lisi S, Mazzon I, White K. Diverse domains of THREAD/DIAP1 are required to inhibit apoptosis induced by REAPER and HID in Drosophila. Genetics. 2000;154:669–678. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hay BA, Wassarman DA, Rubin GM. Drosophila homologs of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis proteins function to block cell death. Cell. 1995;83:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zachariou A, Tenev T, Goyal L, Agapite J, Steller H, et al. IAP-antagonists exhibit non-redundant modes of action through differential DIAP1 binding. Embo J. 2003;22:6642–6652. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson R, Goyal L, Ditzel M, Zachariou A, Baker DA, et al. The DIAP1 RING finger mediates ubiquitination of Dronc and is indispensable for regulating apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:445–450. doi: 10.1038/ncb799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryoo HD, Gorenc T, Steller H. Apoptotic cells can induce compensatory cell proliferation through the JNK and the Wingless signaling pathways. Dev Cell. 2004;7:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shapiro PJ, Hsu HH, Jung H, Robbins ES, Ryoo HD. Regulation of the Drosophila apoptosome through feedback inhibition. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1440–1446. doi: 10.1038/ncb1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suzuki Y, Nakabayashi Y, Takahashi R. Ubiquitin-protein ligase activity of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein promotes proteasomal degradation of caspase-3 and enhances its anti-apoptotic effect in Fas-induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8662–8667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161506698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang H, Joazeiro CA, Bonfoco E, Kamada S, Leverson JD, et al. The inhibitor of apoptosis, cIAP2, functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase and promotes in vitro monoubiquitination of caspases 3 and 7. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26661–26664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schile AJ, Garcia-Fernandez M, Steller H. Regulation of apoptosis by XIAP ubiquitin-ligase activity. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2256–2266. doi: 10.1101/gad.1663108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ditzel M, Broemer M, Tenev T, Bolduc C, Lee TV, et al. Inactivation of Effector Caspases through non-degradative Polyubiquitylation. Molecular Cell. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.025. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan Y, Bergmann A. The cleaved-Caspase-3 antibody is a marker of Caspase-9-like DRONC activity in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:534–539. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pfleger CM, Harvey KF, Yan H, Hariharan IK. Mutation of the Gene Encoding the Ubiquitin Activating Enzyme Uba1 Causes Tissue Overgrowth in Drosophila. Fly. 2007;1:95–105. doi: 10.4161/fly.4285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silke J, Kratina T, Chu D, Ekert PG, Day CL, et al. Determination of cell survival by RING-mediated regulation of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) protein abundance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16182–16187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502828102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryoo HD, Bergmann A, Gonen H, Ciechanover A, Steller H. Regulation of Drosophila IAP1 degradation and apoptosis by reaper and ubcD1. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:432–438. doi: 10.1038/ncb795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hays R, Wickline L, Cagan R. Morgue mediates apoptosis in the Drosophila melanogaster retina by promoting degradation of DIAP1. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:425–431. doi: 10.1038/ncb794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holley CL, Olson MR, Colon-Ramos DA, Kornbluth S. Reaper eliminates IAP proteins through stimulated IAP degradation and generalized translational inhibition. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:439–444. doi: 10.1038/ncb798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wing JP, Schreader BA, Yokokura T, Wang Y, Andrews PS, et al. Drosophila Morgue is an F box/ubiquitin conjugase domain protein important for grim-reaper mediated apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:451–456. doi: 10.1038/ncb800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoo SJ, Huh JR, Muro I, Yu H, Wang L, et al. Hid, Rpr and Grim negatively regulate DIAP1 levels through distinct mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:416–424. doi: 10.1038/ncb793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolff T, Ready DF. The beginning of pattern formation in the Drosophila compound eye: the morphogenetic furrow and the second mitotic wave. Development. 1991;113:841–850. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.3.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cagan RL, Ready DF. The emergence of order in the Drosophila pupal retina. Dev Biol. 1989;136:346–362. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ellis MC, O'Neill EM, Rubin GM. Expression of Drosophila glass protein and evidence for negative regulation of its activity in non-neuronal cells by another DNA-binding protein. Development. 1993;119:855–865. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin FA, Perez-Garijo A, Morata G. Apoptosis in Drosophila: compensatory proliferation and undead cells. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:1341–1347. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072447fm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huh JR, Guo M, Hay BA. Compensatory proliferation induced by cell death in the Drosophila wing disc requires activity of the apical cell death caspase Dronc in a nonapoptotic role. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1262–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Perez-Garijo A, Martin FA, Morata G. Caspase inhibition during apoptosis causes abnormal signalling and developmental aberrations in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:5591–5598. doi: 10.1242/dev.01432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Perez-Garijo A, Shlevkov E, Morata G. The role of Dpp and Wg in compensatory proliferation and in the formation of hyperplastic overgrowths caused by apoptotic cells in the Drosophila wing disc. Development. 2009;136:1169–1177. doi: 10.1242/dev.034017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wells BS, Yoshida E, Johnston LA. Compensatory proliferation in Drosophila imaginal discs requires Dronc-dependent p53 activity. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1606–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.cub2006.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Daish TJ, Cakouros D, Kumar S. Distinct promoter regions regulate spatial and temporal expression of the Drosophila caspase dronc. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:1348–1356. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cakouros D, Daish TJ, Kumar S. Ecdysone receptor directly binds the promoter of the Drosophila caspase dronc, regulating its expression in specific tissues. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:631–640. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abrams JM, White K, Fessler LI, Steller H. Programmed cell death during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1993;117:29–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Muro I, Monser K, Clem RJ. Mechanism of Dronc activation in Drosophila cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5035–5041. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature. 1997;388:300–304. doi: 10.1038/40901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roy N, Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. The c-IAP-1 and c-IAP-2 proteins are direct inhibitors of specific caspases. EMBO J. 1997;16:6914–6925. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Takahashi R, Deveraux Q, Tamm I, Welsh K, Assa-Munt N, et al. A single BIR domain of XIAP sufficient for inhibiting caspases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7787–7790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sun C, Cai M, Gunasekera AH, Meadows RP, Wang H, et al. NMR structure and mutagenesis of the inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein XIAP. Nature. 1999;401:818–822. doi: 10.1038/44617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sun C, Cai M, Meadows RP, Xu N, Gunasekera AH, et al. NMR structure and mutagenesis of the third Bir domain of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein XIAP. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33777–33781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Srinivasula SM, Hegde R, Saleh A, Datta P, Shiozaki E, et al. A conserved XIAP-interaction motif in caspase-9 and Smac/DIABLO regulates caspase activity and apoptosis. Nature. 2001;410:112–116. doi: 10.1038/35065125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shiozaki EN, Chai J, Rigotti DJ, Riedl SJ, Li P, et al. Mechanism of XIAP-mediated inhibition of caspase-9. Mol Cell. 2003;11:519–527. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Riedl SJ, Renatus M, Schwarzenbacher R, Zhou Q, Sun C, et al. Structural basis for the inhibition of caspase-3 by XIAP. Cell. 2001;104:791–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chai J, Shiozaki E, Srinivasula SM, Wu Q, Datta P, et al. Structural basis of caspase-7 inhibition by XIAP. Cell. 2001;104:769–780. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Silke J, Hawkins CJ, Ekert PG, Chew J, Day CL, et al. The anti-apoptotic activity of XIAP is retained upon mutation of both the caspase 3- and caspase 9-interacting sites. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:115–124. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wertz IE, Dixit VM. Signaling to NF-kappaB: regulation by ubiquitination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003350. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Herman-Bachinsky Y, Ryoo HD, Ciechanover A, Gonen H. Regulation of the Drosophila ubiquitin ligase DIAP1 is mediated via several distinct ubiquitin system pathways. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:861–871. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Adhikari A, Xu M, Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin-mediated activation of TAK1 and IKK. Oncogene. 2007;26:3214–3226. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hay BA, Wolff T, Rubin GM. Expression of baculovirus P35 prevents cell death in Drosophila. Development. 1994;120:2121–2129. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bergmann A, Steller H. Apoptosis, stem cells, and tissue regeneration. Sci Signal. 2010;3:re8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3145re8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fan Y, Bergmann A. Apoptosis-induced compensatory proliferation. The Cell is dead. Long live the Cell! Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tabata T. Genetics of morphogen gradients. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:620–630. doi: 10.1038/35084577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yu SY, Yoo SJ, Yang L, Zapata C, Srinivasan A, et al. A pathway of signals regulating effector and initiator caspases in the developing Drosophila eye. Development. 2002;129:3269–3278. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.13.3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fan Y, Lee TV, Xu D, Chen Z, Lamblin AF, et al. Dual roles of Drosophila p53 in cell death and cell differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:912–921. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Herz HM, Chen Z, Scherr H, Lackey M, Bolduc C, et al. vps25 mosaics display non-autonomous cell survival and overgrowth, and autonomous apoptosis. Development. 2006;133:1871–1880. doi: 10.1242/dev.02356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leulier F, Ribeiro PS, Palmer E, Tenev T, Takahashi K, et al. Systematic in vivo RNAi analysis of putative components of the Drosophila cell death machinery. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1663–1674. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.White K, Tahaoglu E, Steller H. Cell killing by the Drosophila gene reaper. Science. 1996;271:805–807. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Emery G, Hutterer A, Berdnik D, Mayer B, Wirtz-Peitz F, et al. Asymmetric Rab 11 endosomes regulate delta recycling and specify cell fate in the Drosophila nervous system. Cell. 2005;122:763–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Morrison CM, Halder G. Characterization of a dorsal-eye Gal4 Line in Drosophila. Genesis. 2010;48:3–7. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhou L, Schnitzler A, Agapite J, Schwartz LM, Steller H, et al. Cooperative functions of the reaper and head involution defective genes in the programmed cell death of Drosophila central nervous system midline cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5131–5136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xu T, Rubin GM. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–1237. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Newsome TP, Asling B, Dickson BJ. Analysis of Drosophila photoreceptor axon guidance in eye-specific mosaics. Development. 2000;127:851–860. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.4.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) for Drosophila neural development. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:251–254. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01791-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Grether ME, Abrams JM, Agapite J, White K, Steller H. The head involution defective gene of Drosophila melanogaster functions in programmed cell death. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1694–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Loss of ark suppresses apoptosis in Uba1 clones. Uba1 ark mosaic eye-antennal disc labeled for cleaved CASPASE-3 (CAS3*) antibody (red). These discs were incubated at 30°C 12 hours before dissection (see Material and Methods). Absence of GFP marks the location of Uba1 ark clones (see arrows). There is scattered apoptosis detectable. However, this occurs throughout the disc and does not correlate with the positions of the Uba1 ark double mutant clones. Genotype: ey-FLP; FRT42D Uba1D6 arkG8/FRT42D ubi-GFP.

(TIF)

UAS-diap1 rescues GMR-hid and apoptosis induced in vps25 mutants. Because the UAS-diap1 transgene failed to suppress apoptosis in Uba1 clones (Figure 1C), we tested its ability to inhibit the strong apoptotic phenotype in two other paradigms. (A) Overexpression of the IAP-antagonist hid specifically in the fly eye under GMR promoter control gives rise to a strong eye ablation phenotype due to massive induction of apoptosis [100]. (B) Coexpression of UAS-diap1 partially suppresses the GMR-hid eye ablation phenotype [42]. (C) vps25 mutant clones induce a strong apoptotic phenotype. vps25 encodes an component involved in endosomal protein sorting [90]. The apoptotic phenotype of vps25 and Uba1 as well as other phenotypes caused by inactivation of these genes are very similar, and both mutants were obtained in the same genetic screen [5], [90]. The left panel is the merge of GFP and anti-cleaved CASPASE-3 (CAS3*) labeling, the right panel (C′) displays only the CAS3* channel. White arrows mark a few clones as examples. (D) Overexpression of diap1 completely suppresses the strong apoptotic phenotype of vps25 mutant clones. The experimental conditions applied here are identical to the Uba1 experiment in Figure 1C. The left panel is the merge of GFP and anti-cleaved CASPASE-3 (CAS3*) labeling, the right panel (D′) displays only the CAS3* channel. Genotype: hs-FLP UAS-GFP/UAS-diap1; FRT42D vps25N55/FRT42D tub-Gal80; tub-GAL4. Genotypes: (A) GMR-hid GMR-GAL4. (B) UAS-diap1; GMR-hid GMR-GAL4. (C) ey-FLP; FRT42D vps25N55/FRT42D P[ubi-GFP]. (D) ey-FLP; FRT42D vps25N55/FRT42D P[ubi-GFP].

(TIF)

Specificity of the anti-DRONC antibody. The specificity of the anti-DRONC antibody used for immunofluorescence in Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5 was verified in droncI29 mosaic eye (A) and wing (B) imaginal discs. The droncI29 allele contains a premature STOP codon at position 53 [11]. droncI29 clones were induced using the MARCM system, hence they are positively marked by GFP (arrows). The anti-DRONC antibody does not produce labeling signals in the mutant clones (arrows in A′ and B′, and the merge in A″ and B″), demonstrating that it is specific for DRONC. Genotype: hs-FLP; droncI29 FRT80/ubi-GFP FRT80.

(TIF)

“Undead” diap122-8s cells accumulate DRONC protein autonomously. (A, A′) Using MARCM, p35-expressing, ‘undead’ diap122-8s mutant clones (green) were induced in eye discs and labeled for DRONC protein (red). DRONC protein autonomously accumulates in P35-expressing diap122-8s clones (arrows). Similar results were obtained in wing discs (data not shown). Genotype: hs-FLP tub-GAL4 UAS-GFP/+; UAS-p35/+; diap122-8s FRT80/tub-GAL80 FRT80.

(TIF)