Abstract

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a widely accepted psychosocial treatment for chronic pain. However, the efficacy of CBT has not been investigated within a rural setting. Furthermore, few studies have utilized first-person accounts to qualitatively investigate the key treatment elements and processes of change underlying the well-documented quantitative improvements associated with CBT. To address these gaps, we conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigating the efficacy of group CBT compared to an active education condition (EDU) within a rural, low-literacy population. Post-treatment semi-structured interviews of 28 CBT and 24 EDU treatment completers were qualitatively analyzed. Emerging themes were collated to depict a set of finalized thematic maps to visually represent the patterns inherent in the data. Patterns were separated into procedural elements and presumed change processes of treatment. Key themes, subthemes, and example extracts for CBT and EDU are presented; unique and shared aspects pertaining to the thematic maps are discussed. Results indicate that while both groups benefited from the program, the CBT group described more breadth and depth of change as compared to the EDU group. Importantly, this study identified key treatment elements and explored possible processes of change from the patients’ perspective.

Perspective

This qualitative article describes patient-identified key procedural elements and change process factors associated with psychosocial approaches for chronic pain management. Results may guide further adaptations to existing treatment protocols for use within unique, underserved chronic pain populations. Continued development of patient-centered approaches may help reduce health, treatment and ethnicity disparities.

Keywords: Randomized Controlled Trial, Qualitative Analysis, Chronic Pain, Rural, Low-literacy

Introduction

Chronic pain is a major healthcare concern, with estimated worldwide lifetime prevalence rates exceeding 35%.36 It has been reported that over 205 million Americans have severe headache, back pain, neck pain, or face pain.26 Annual income of less than $25,000, no high school diploma, and rural residency are associated with a greater likelihood of having disabling chronic pain.13,35,40 An abundance of research suggests that low-socioeconomic status (SES) predicts poor pain adjustment.e.g.,1,11,16,21,29,30

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has demonstrated efficacy for a variety of chronic pain conditions and is at least as efficacious as other medically-based treatments.7 Conceptually, CBT for chronic pain is based on the biopsychosocial model,9 highlighting important interactions among biological, psychological, and social variables. The premise of CBT is that patient’s thoughts and behaviors are key processes through which adaptive adjustment to chronic pain takes place. Within primarily White-American urban populations, CBT has been shown to decrease pain, interference due to pain, work absenteeism, and medication use, and improve mood and activity levels.e.g.,17,25,32,44 Psychoeducational interventions have also been shown to be beneficial.e.g.,33,34,48 Moseley and colleagues (2002) theorize that provision of information to patients about chronic pain promotes a reconceptualization of the problem, which may, in turn, improve pain-related outcomes.34 However, the efficacy of CBT or educational interventions for chronic pain has not been specifically investigated within low-SES populations.

To address this gap in the literature, we conducted a community-based randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigating the feasibility and efficacy of a cognitively-focused group CBT program in comparison with an active group education condition (EDU) within a low-SES rural Alabama population. The manualized treatments8,42 were adapted to be culturally sensitive23 and treatment outcome was assessed via quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Although most available efficacy research on chronic pain has focused on quantitative outcomes rather than qualitative outcomes, we additionally implemented a qualitative approach to provide important, augmenting information. The qualitative arm of the study was thought to be particularly relevant considering the unique, understudied and undertreated population that we targeted. Thus, at post-treatment, a semi-structured interview was completed to explore participants’ experiences with the pain management program. Specifically, we examined participant perceptions of salient procedural elements of treatment as well as perceived barriers to treatment feasibility and efficacy. Furthermore, via the qualitative methodology, we sought clues regarding possible underlying change processes associated with the reported quantitative improvement in pain-related outcomes.

Results of this study are to be presented at the forthcoming annual American Pain Society meeting (2011).

Methods

Design

The current study was conducted in three rural Alabama counties (Pickens, Wilcox, and Walker). All participants who completed the 10-week CBT or EDU program were offered the opportunity to participate in a post-treatment, semi-structured interview. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed independently by three experienced coders; the qualitative analytic approach was based on thematic analysis. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama, and informed consent was obtained with all patients prior to participation.

Participants

The sample consisted of adult chronic pain patients with heterogeneous chronic pain conditions living in rural Alabama counties and attending federally qualified (low income) primary health clinics. All 61 patients who completed treatment participated in the post-treatment semi-structure interview. However, due to technological malfunctions (i.e., failure of the digital recorder to record the interview) data from 9 of the interviews were not available for qualitative analysis. Thus, the final sample of 52 interviews (28 for CBT, and 24 for EDU) were ultimately analyzed. See Table 1 for the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Patient demographic characteristics (N=52)

| Variable | Mean (SD) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 53.25 (+/− 12.31) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 20 | |

| Female | 80 | |

| Race | ||

| White-American | 22 | |

| African-American | 78 | |

| Disability Status | ||

| On disability | 49 | |

| Seeking disability | 18 | |

| Not on, not seeking | 32 | |

| Income | ||

| $0 to $12,999 | 57 | |

| $13,000 to $24,999 | 22 | |

| $25,000 to $49,000 | 20 | |

| $50,000 & above | 2 | |

| Employment Status | ||

| Employed | 14 | |

| Unemployed | 54 | |

| Retired | 28 | |

| Home-maker | 4 | |

| Education | 13.0 (+/−2.05) | |

| Reading Grade Level | 7.94 (+/− 3.43) | |

| Primary Pain Type | ||

| Low back pain | 41 | |

| Arthritis | 29 | |

| Headache | 4 | |

| Other (e.g., IBS, Fibromyalgia, Neuropathic Pain) | 16 | |

Interventions

The group-administered, 10-week CBT and EDU intervention protocols were adapted from Thorn (2002) and Ehde et al. (2005) respectively.8,42 The adaptations addressed the limited literacy of the population and tailored the program to rural Alabama patients, remaining sensitive to any adjustments needed based on differences in income, race/ethnicity, and culture (see Kuhajda et al, 2010 for details regarding the adaptation process).23 All EDU sessions focused on providing factual information about pain and its sequelae, but did not include skills-building exercises that were part of the CBT intervention (such as learning skills to deal with thoughts, feelings, and behavior, or participating in relaxation or other behavioral exercises). Groups in both conditions lasted 90 minutes, were led by trained graduate students and licensed psychologists, and sought to maximize patient rapport with therapists, group cohesion, and group discussion related to the weekly topics. Participants in both conditions were given a client manual with materials and handouts they could follow/discuss during sessions, and read between sessions and after conclusion of the intervention period.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

A general outline of the objectives of each CBT session is as follows: Session 1) establish rapport, explain therapy rationale, goals, format and rules, introduce stress-appraisal-pain connection; Session 2) identification of negative automatic thoughts; Session 3) evaluate automatic thoughts for accuracy; Session 4) challenge distorted automatic thoughts, construct realistic alternative responses; Session 5) identify intermediate belief systems, challenge negative distorted beliefs, construct new beliefs; Session 6) identify core beliefs, challenge negative, distorted core beliefs, construct new, more adaptive beliefs; Session 7) relaxation exercise, positive coping self-statements; Session 8) expressive writing or verbal narration of expressive writing exercise; Session 9) assertive communication; and Session 10) review concepts and skills learned, provide feedback about helpful and challenging aspects of the treatment. All learning objectives were presented by the group leaders and interactive skills-building exercises and group discussion followed. Homework assignments included instructions to think, do, and write thoughts and reactions to the assignments.

Education (EDU)

A general outline of the objectives of each EDU session includes: Session 1) establish rapport, explain therapy rationale, goals, format and rules, introduce concepts in chronic pain treatment; Session 2) Gate Control Theory of Pain; Session 3) costs of chronic pain; Session 4) acute versus chronic pain; Session 5) sleep (i.e., normal sleep, sleep disorders, sleep hygiene); Session 6) depression and other mood changes associated with chronic pain; Session 7) pain behaviors; Session 8) pain and communication (i.e., assertive, aggressive, and passive communication styles); Session 9) working with health care providers; Session 10) stages of change, review concepts learned, provide feedback about helpful and challenging aspects of the treatment. All learning objectives were presented by the group leaders and interactive group discussion followed; no homework was assigned to EDU participants.

Data collection

At post-treatment, CBT and EDU completers answered a number of open-ended questions that followed a semi-structured interview format, in a one-to-one setting. Interviews were conducted by a trained member of the research team (i.e., primarily a licensed clinical psychologist or a clinical psychology graduate student) who was not involved in leading the intervention, and lasted between 10- to 45-minutes. All interviews were conducted within one week of the participant completing treatment.

The interview protocol begins with questions designed to build rapport with participants, followed by a series of questions designed to elicit participants’ feedback regarding their direct experiences with the program, and the usefulness and difficulty of different aspects of the treatment. During the course of the interview, the interviewers frequently re-worded, re-ordered, and/or clarified the questions to further investigate topics introduced by the respondent. All interviews conducted were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist. The key interview questions included in the interview were:

What was it that made you decide to go ahead and join the group?

How did you feel about the questions we asked you before and after each group?

Describe for me the most important or useful ways to deal with pain that you learned from the group meetings?

What were some things covered in the group meetings that were not useful for you?

What do you do differently now based on what you’ve learned in the group?

How did you feel about the weekly homework assignments? (CBT Subjects Only)

Analytic Approach

A qualitative analysis of the data obtained in the post-treatment, semi-structured interviews was primarily conducted using a thematic analytic approach using the guidelines described by Braun and Clarke.4 Thematic analysis is a flexible analytic method that refers to the identification and interpretation of recurrent patterns (themes) within the data set that may be either inductively or theoretically generated.4 This qualitative analytic approach is widely used within psychology,4 and health care research in general,39 and is arguably the most commonly employed qualitative strategy in the social sciences.14 First, interviews were reviewed in their entirety by three experienced coders (authors). The coding team then went through an iterative process of independently reviewing sets of 5 CBT and 5 EDU interviews, followed by meeting to discuss, resolve discrepancies, and revise the consensus codebook, until all interviews (28 for CBT, and 24 for EDU) were coded. After coding all of the interviews, each coder independently sorted the codes into potential themes and sub-themes and all relevant coded data extracts were collated within these themes. The coding team then reconvened to compare their identified themes, and to generate an initial thematic map (i.e., visual representation) depicting a consensus of the candidate main themes and sub-themes emerging from the data. The primary author then reviewed the collated coded extracts for each candidate theme, checking that the themes formed a coherent pattern. The validity of each theme and the accuracy of the thematic map were considered in relation to the overarching meaning inherent in the data set as a whole. The coding team then collectively defined and refined the themes to generate final thematic maps. Content analysis was then conducted to calculate the percentages of participants whose statements were contained within each theme.

Results

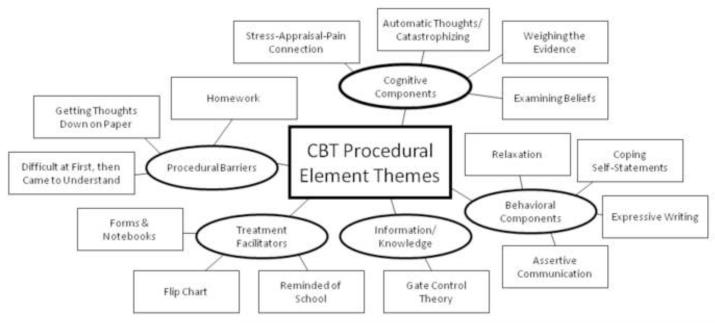

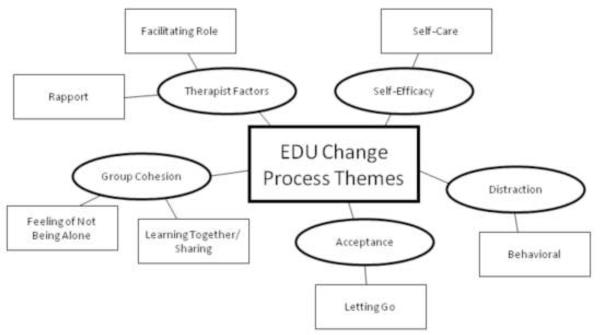

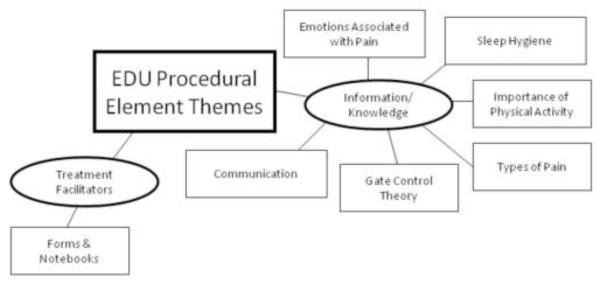

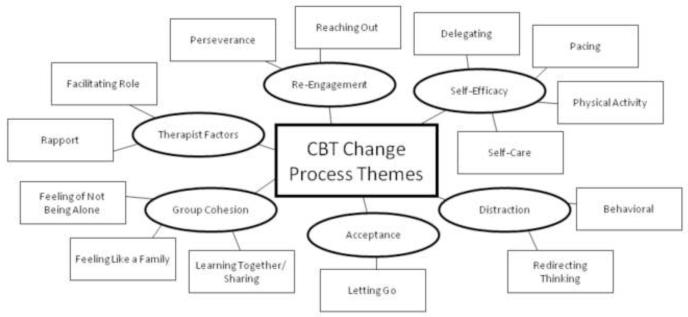

See Figures 1-4 for final thematic maps depicting the patterns that emerged from the data. These patterns were separated into procedural elements and presumed change processes of treatment. Examples of procedural elements of treatment include mention of particular topics covered during sessions, comments regarding specific skills taught, participant acknowledgment of learning tools used to facilitate communication of the concepts, and perceived barriers to treatment. See Table 2 and Table 3 for example extracts corresponding to themes and subthemes for CBT and EDU procedural elements. Examples of presumed change processes include participant acknowledgment of therapist factors such as caring, rapport, or their skillful implementation of the treatment, mention of factors associated with group cohesion, and participant descriptions of psychological factors that have been linked to the conceptual model(s) underlying psychosocial treatment (e.g., improved self-efficacy). See Table 4 and Table 5 for extracts representative of CBT and EDU change process themes and subthemes. Themes and subthemes are reported (in detail below) and include the percentage of participants whose statements were contained within these themes. It is important to note that these percentages are not intended to convey statistical significance; we calculated the percentages in order to determine the relative salience/importance of the emerging themes and subthemes. Participants were not limited in terms of the breadth and/or depth of their responses, therefore participants may have reported information relevant to several themes/subthemes. Hence, some overlap exists in terms of the percentage of participants reporting specific themes/subthemes.

Figure 1.

CBT thematic map depicting procedural elements

Figure 4.

EDU thematic map depicting change processes

Table 2.

CBT procedural element themes and sample extracts from the post-treatment, semi-structured interviews

| Themes | Example |

|---|---|

| Cognitive Components | |

| Stress-Appraisal-Pain Connection | “Where your mind is, your body is, also. If your mind is in a stressful or negative situation, then your body’s gonna suffer from that.” (55 year-old, AA male) |

| Automatic thoughts/Catastrophizing | “The automatic thought process - usually when something jumps in your head, don’t have all the right reason but it end up in there, and you always take the worst and put in there.” (50 year-old, AA male) |

| Weighing the Evidence | “The session of it where you weigh the truth, what really was and what wasn’t, and that was cool because once we looked into it, it really wasn’t as bad as we thought it was.” (50 year-old, AA male) |

| Examining Beliefs | “…the “should” belief are the things that I had embedded so deep inside… just saying, Well, I’ve got to do it, or I should be able to do this, and all these things and just realizing how we can work it and get the problem solved… when we got to the end, we saw that it wasn’t always 100%, that there was a different alternate to work out our problems.” (52 year-old, AA female) |

| Behavioral Components | |

| Relaxation | “…because really once you get your body relaxed and your mind relaxed, the pain kind of smooth away.” (52 year-old, AA male) |

| Coping Self-Statements | “And then the cards that we made, like I have a card in my mirror and I have one over my sink… I mean, I’m not taking them down. On my mirror, it says, Good morning, Beautiful. And when I brush my teeth, I always refer to that one. So that gives me a smile to send me on my way.” (36 year-old, AA female) |

| Expressive Writing | “We had to write about something that was on our mind and had been troubling us. And it brought up a bad memory for me. I didn’t like that. But it was something that I guess you could say it was good to deal with, because I really haven’t thought about it ever since I wrote it that day.” (60 year-old, AA female) |

| Assertive Communication | “I learned not to say “yes” every time somebody asks you to do something. If I say “no,” just say it in a pleasant voice, not like I’m upset or anything. Just say it and say “no” with a smile.” (68 year-old, AA female) |

| Information/Knowledge | |

| The Gate Control Theory | “That is the one that stands out the most, the gates. A lot of times if you understand something, you can cope with it better.” (67 year-old, WA female) |

| General | “Well, it explained a lot. Like I said, we really don’t focus on different things, so it really broke things down. It had a little about our emotions. It just took us through every step about our body that we really wouldn’t - I wouldn’t have ‘thought’ of it.” (52 year-old, AA female) |

| Treatment Facilitators | |

| Forms (Pre- and Post-Session Process Checks) |

“It let you express how you felt and what you were going through. And then, like the things that you learned, they would go over to see that you understood it, or, did you get confused?” (52 year-old, AA female) |

| Notebooks | “Well, it helped me because I’m going back when I get back home, I’m going to review it and all, and I find it’s helpful because I can – if I got pain, I can start thinking about how I can control the pain and all and thinking of different things in the book to do, and I find it’s working.” (73 year-old, AA female) |

| Flip chart | “I liked it so much… she had the little board and she’d call on us to do a different scenario and then you would say it out of the class… and just to sit up there and look at it and then you working through problem-solving, working on through it.” (52 year-old, AA female) |

| Reminded of School | “I took the class as, like I said, pain management. And I went there and I listened at them talk and look at our notes and go over things and it just made me feel a whole lot better because, you know, I didn’t finish school, but coming to the class, it helped me. Felt like I was back in a classroom again and going through classes, and I really love it.” (34 year-old, AA female) |

| Procedural Barriers | |

| Getting Thoughts Down on Paper | “I know I’m getting something, but I can’t put it down on paper.” (60 year-old, WA male) |

| Difficult at First, then Came to Understand | “At first I was having a hard time focusing and I’m like, well, this is not gonna work. Then as I got into it and I began to think, yeah, it really can because I have a lot of stress and when you stress out about a lot of things, this doesn’t help the pain at all.” (48 year-old, AA female) |

| Problems with Homework | “I’ve been out of school for so long, it was hard. But once I got to – you had so much to write about, and I used to always go back and look at things, why you really thought that way, why you really felt that way, and it’s good to have things written down.” (37 year-old, AA female) |

Table 3.

EDU procedural element themes and sample extracts from the post-treatment, semi-structured interviews

| Themes | Example |

|---|---|

| Information/Knowledge | |

| The Gate Control Theory | “When we was talking about that gate, that narrowing that gate and opening that gate, how we could open that gate our own self instead of narrowing that gate. Now, I really liked that part the most because it gave me the idea that I can make this pain worser or either I can make this pain better.” (46 year-old, AA female) |

| Types of Pain | “Because before I took the group, I didn’t know none of that – all the types of pain we talked about and stuff.” (48 year-old, AA female) |

| Sleep Hygiene | “We learned about the sleep patterns and what we should and shouldn’t do before we go to bed.” (45 year-old, WA female) |

| Communication | “The communication part has helped me to talk and communicate with my family peoples, the ones that are inside the home with me, and to communicate with peoples in general. If I’m not having a good day or whatnot, it just helps me to communicate with everybody to not just blurt out something because a lot of times you can hurt somebody’s feelings by doing that.” (46 year-old, AA female) |

| Importance of Physical Activity | “What I learned is that when you’re dealing with chronic pain, you need to try to get up, you need to try to stretch those muscles, you need to try to exercise. You need to try to do something to build your muscle mass up so that way it’ll take the pressure off other parts of your body.” (35 year-old, AA male) |

| Emotions Associated with Pain | “The one that I learned was mostly to deal with my anxieties and depression, because I really had to work hard at that because I would lash out at people when I was in pain and I had to learn how to control that and just try to talk about it more, be more open. I was thinking that they could see my pain, and they couldn’t. I would close myself off, but once I started opening up and talking about it, I could feel the pressure easing off of me.” (47 year-old, AA female) |

| Treatment Facilitators | |

| Forms | “…the jotting down would kind of like refresh your memory of what you talked about.” (55 year-old, AA female) |

| Notebooks | “Without this notebook, I promise you I didn’t know none of this stuff was going on… My book’s helping me in every way to learn more about the facts of chronic pain and how to deal with it.” (46 year-old, AA female) |

Table 4.

CBT change process themes and sample extracts from the post-treatment, semi-structured interviews

| Themes | Example |

|---|---|

| Group Cohesion | |

| Feeling of Not Being Alone | “It’s just good to have someone to talk to and let you know that you’re not alone.” (47 year-old, AA female) |

| Learning Together/Sharing | “You would get so involved, and when you’d get stuck in a spot it looked like everybody knew what you were going through and we’d just kind of help each other to work through the different scenarios and just tell some of the things that we were going through. Again, for me, the being able to speak out.” (52 year-old, AA female) |

| Feeling Like a Family | “I mean, like I said, the group was just like sitting around with friends and just so homely, I mean, especially on Friday. We all looked forward to coming on Friday to sit around, so it just felt like a big family.” (48 year-old, AA female) |

| Therapist Factors | |

| Rapport | “It was very warm, the environment was quite relaxing, their tone of voice captured the audience. We were always on our toes because we wanted to keep up with our professors. So it was just very, very warm and relaxing atmosphere.” (60 year-old, AA female) |

| Facilitating role | “The way they explain and they listen. Even if it was something that we were trying to say, and we couldn’t get it out all together, they related to it. They could help bring it out for us.” (52 year-old, AA female) |

| Self-Efficacy | |

| General | “So it won’t necessarily be that we won’t have any pain after the class is over, but we will know more better how to deal with the pain and not let it take us on instead of us take it on.” (52 year-old, AA female) |

| Self-Care | “And just I guess the main thing I got at the end of the class is just to spend some time for me and to enjoy life. And Dr. Thorn told us a thought that I just guess I’ll carry for the rest of my life: Self-care is not selfish.” (52 year-old, AA female) |

| Delegating | “I’ve also learned about delegating, I don’t have to do everything. I can speak up and say, No, I can’t do this today or I can’t go here or something. And if I don’t do it, everybody’s gonna be okay. Still gonna live, still gonna breathe and go on. So delegating allows me to, yes, be more outspoken with things.” (52 year-old, AA female) |

| Pacing | “I pace myself now. I take my time with everything, do everything at my convenience. Not overdo.” (49 year-old, AA female) |

| Physical Activity | “I learned that we don’t have to rely on medicine all the time. Get up and do exercise and things like that.” (62 year-old, AA female) |

| Distraction | |

| Behavioral | “Well, I find helpful that, you know, even if you’re hurting, you don’t have to just sit around all the time. Try to get up and go and get in conversation with other peoples and things. That’s helped me to forget.” (68 year-old, AA female) |

| Redirecting Thinking | “One thing I learned about dealing with pain is that you don’t need to think about pain all the time. You need to relax yourself and don’t let the worrying take you to another stage that you’re not in.” (59 year-old, AA male) |

| Acceptance | |

| General | “Because of the sessions, it changed my whole attitude on life, changed how I feel about others, changed how I feel about the pain, because I have arthritis and I hardly think about it. If it’s there, it’s there, you know.” (60 year-old, AA female) |

| Letting Go | “A lot of times you get with your thoughts, or get hung up on them, what you feel inside. So really the group explained how each one of those play a part. Stuff that we build up inside of us, how we can let it go. So, it was very helpful, because really when you think about it you don’t go through with your thought and all of that. You just finally let it go.” (52 year-old, AA female) |

| Re-engagement | |

| Perseverance | “But even with the pain, you can rise above it. You continue. You don’t stop.” (55 year-old, AA male) |

| Reaching Out | “I’ll get out more, try to do more social activities… instead of sitting home every day doing nothing, I try to get out and try to help things, help people in the community or in my church.” (48 year-old, AA female) |

Table 5.

EDU change process themes and sample extracts from the post-treatment, semi-structured interviews

| Themes | Example |

|---|---|

| Group Cohesion | |

| Feeling of Not Being Alone | “I was feeling like I was so alone, and I found out better, that other people were going through it, too.” (47 year- old, AA female) |

| Learning Together/Sharing | “It’s better to talk about it in a group and how each, everybody feels, you know. Until then, you know, I didn’t know how I was feeling until I heard all the other ladies tell about their stories and how their pain affects their daily life and stuff. So I understood it then…” (48 year-old, AA female) |

| Therapist Factors | |

| Rapport | “And everybody still did not know you all had a schedule. You all didn’t get impatient or anything. Some people probably had things held in that they just didn’t know how to relate or communicate about, thought nobody wanted to hear. But it was good that you all and the other members that was involved was able to listen to them.” (48 year-old, AA female) |

| Facilitating Role | “Yes, because we don’t get this down here and it was exciting for somebody to come out and take time with us and try to help us learn stuff that we don’t know… And they learned me ways to do and get around that and relax and take time.” (50 year-old, AA female) |

| Self-efficacy | |

| General | “It helped me get control over it. Instead of the pain controlling me, it helped me learn how to control my pain.” (34 year-old, AA female) |

| Self-care | “I made a commitment the last time I was here that I’m gonna start doing better. Even my eating habits, trying to exercise just a little bit to help with the weight problem, and the weight problem will come off a little bit and that will help with the pain. So I’m trying to get an idea of how I can do things and get things going to keep the pain not so bad.” (46 year-old, AA female) |

| Distraction | |

| Behavioral | “For me it was to get up and move around during the day, not lay back there and dwell on the pain. Get up and do some of my normal activities… So once I got up and got stirring around, most of my pain is in my knees, arthritis. And once I got up and start moving around, it’d tend to go away somewhat.” (63 year-old, AA female) |

| Acceptance | |

| General | “I didn’t feel about it at all. It was just something I just wanted to go away, you know. It taught us how to deal with it and how to live life with it.” (48 year-old, AA female) |

| Letting Go | “I found a way through that studying to let that stuff go. There were some things that were just totally out of my power and I had to realize that and I just had to live and be me.” (35 year-old, AA male) |

Procedural Element Themes

Thirty-six percent of the 28 CBT participants and 96% of the 24 EDU participants noted that they found the information/knowledge conveyed to them by the therapist as useful. In CBT, participants’ comments about the importance of the information presented were more general in nature (25%); however, several CBT participants also made specific reference to usefulness of learning about the Gate Control Theory of Pain (14%). Participants in EDU consistently noted numerous specific educative components of the protocol as helpful; key subthemes included information regarding communication (50%), sleep hygiene (29%), the importance of physical activity (21%), learning about common emotions associated with chronic pain (21%), types of pain (17%), and again, the Gate Control Theory (29%).

Seventy-one percent of CBT participants commented that specific cognitive-behavioral skills taught were of benefit. Cognitive component subthemes that were highlighted by participants included the stress-appraisal-pain connection (36%), automatic thoughts/catastrophizing (21%), weighing the evidence (18%), and examining beliefs (46%). Behavioral components were also positively evaluated by the CBT participants. While all behavioral components included in the treatment were commented on, the most frequently mentioned component was relaxation (75%), followed by assertive communication (43%), expressive writing (36%), and coping self-statements (14%).

Eighty-two percent of CBT participants and 92% of EDU participants commented upon factors that facilitated treatment and assisted with learning and patient integration of the concepts within the CBT and EDU treatments. Many participants (57% for CBT, and 58% for EDU) noted that the pre- and post-session process check forms were a useful learning tool that assisted with retention of the concepts presented in group and that these forms gave them the opportunity to communicate/express individual feedback to the therapists. The notebooks containing the session handouts were also positively regarded by the majority of participants (79% for CBT, and 67% for EDU). A treatment facilitator uniquely commented on by CBT participants (18%) was the flip chart used in session (where the therapist noted and collaboratively worked through participants’ examples during the group discussions). Although the flip chart was utilized across both conditions, it seems that for CBT participants it was particularly useful in helping them acquire the cognitive-therapy skill-set. Further, CBT participants (29%) also reported a positive association between the groups and school, and that this was a source of motivation to continue coming to the pain management classes. The narrative link between school and the CBT groups was made by several participants (and it was always a positive connotation), and was not mentioned by any EDU participants. This between-group difference may be due to the interactive processes (between group leaders and participants) involved in working through the take-home learning activities assigned only in the CBT groups. It is possible that this collaborative element cued in CBT participants something that simply receiving information did not.

Notably, procedural barriers to completing the treatment program were only mentioned by CBT participants (68%). Participants’ comments frequently referred to the cognitive components of the program as difficult at first but that they eventually came to understand and were able to work with the concepts (36%). CBT participants also reported difficulties with completing the homework activities that utilized the cognitive therapy column technique (46%), and trouble putting their thoughts down on paper (25%).

Change Process Themes

The majority of participants across both conditions noted that group cohesion (64% for CBT, and 75% for EDU) and therapist factors (54% for CBT, and 50% for EDU) in and of themselves were exceptionally valued aspects of the treatment. Of note, the sub-themes underlying these change processes were mostly shared by participants across both conditions. Shared subthemes regarding group cohesion included a feeling of not being alone (32% for CBT, and 29% for EDU) and learning together/sharing (43% for CBT, and 58% for EDU). Several CBT participants also reported that their group felt like a family (18%). Therapist factor subthemes were rapport (39% for CBT, and 33% for EDU), and facilitating role (29% for CBT, and 29% for EDU).

Participants also described psychosocial constructs that have been posited in the literature as potential mechanisms of change associated with psychosocial treatment. Both CBT and EDU participants stated that the program instigated meaningful changes in terms of self-efficacy (57% for CBT, and 33% for EDU), distraction (32% for CBT, and 8% for EDU), and acceptance (54% for CBT, and 21% for EDU). It is interesting to note that while both CBT and EDU participants mentioned factors associated with self-efficacy and distraction, the nature of these factors differed in important ways between the treatments, as shown by the emerging subthemes. For CBT, subthemes underlying self-efficacy included self-care (39%), delegating (7%), pacing (18%), and physical activity (14%); whereas for EDU, while self-efficacy was touched upon, it was more loosely defined and the only clear subtheme emerging was self-care (21%). Additionally, in regards to distraction, while participants in both conditions reported engaging in behavioral activities to take their mind off the pain (18% for CBT, and 8% for EDU), CBT participants (25%) also reported engaging in redirecting thinking such that they could willfully shift their mental focus away from pain. The nature of pain acceptance on the other hand was similar across conditions, as evidenced by the shared sub-theme of letting go (32% for CBT, and 8% for EDU). One specific change process factor theme that emerged uniquely from the CBT data was re-engagement in meaningful activities (46%). Subthemes pertaining to this theme included perseverance (21%) and reaching out (11%).

Discussion

Determining patient-perceived salient procedural elements of biopsychosocial treatments is not a typical component of clinical treatment outcome research. Yet, identification of key treatment elements and accessing the possible cognitive and behavioral processes of change from the patients’ perspective has both pragmatic and theoretical implications in furthering our understanding of pain and its relief. Qualitative approaches provide a means to identify these treatment components previously inaccessible via traditional quantitative methods. This patient-centered approach is particularly important when considering the translation of empirically supported treatments into real-world clinical settings with vulnerable populations.

Using post-treatment, semi-structured interviews, we investigated how the patients related to the various elements of the CBT and EDU interventions, which allowed for examination of patient assimilation of the concepts and ideas of the respective theoretical frameworks of CBT and education. This is the first study to qualitatively compare two biopsychosocial treatments for chronic pain, thus the results provide insight into the potential common and unique change processes inherent in these therapeutic approaches. The relatively large numbers of interviews included in the qualitative analysis increases the trustworthiness, credibility and dependability of the results.

While CBT and EDU have different therapeutic rationales, they share a similar fundamental backdrop in that they are both psychoeducational in nature. This basic structural commonality was verified by participants in both groups, who noted that the informational component of the groups was helpful. EDU participants, however, went into detailed accounts of the specific information that was useful to them. This is consistent with the conceptual basis of educational interventions which emphasizes factual information, which is thought to be efficacious because it may help the patient understand and reconceptualize the problem.34 CBT participants gave less weight to, and fewer details regarding the benefit of factual information, which mirrors the reduced theoretical importance of knowledge acquisition in CBT.

A critical theoretical component of CBT for chronic pain is promoting a more positive and realistic cognitive appraisal of situations initially judged as stressful, such that negative thoughts are addressed before they cascade and potentially instigate poor pain-related outcomes.42 This rationale is supported by neuroimaging research that has found strong support for the idea that negative cognitions can amplify pain signals and change brain circuitry specific to the perception of pain.e.g.,22,24,38 The adapted CBT manual implemented in the present research explicitly emphasized changing the quality and content of maladaptive, negative thoughts/beliefs. Participants in the current study noted that sessions devoted to each of the cognitive restructuring elements were beneficial; however, examination of intermediate and core beliefs particularly resonated with this population. It is important to note that while overwhelmingly described as helpful, the cognitively-focused sessions also posed the greatest barriers to CBT treatment completion. The CBT program was found to be difficult at first and the traditional column technique worksheets created unique challenges for this low-literacy population. Of note, quantitative analyses (Thorn et al., manuscript in preparation; research conducted in 2007-2010) found that frequency of drop-out was higher in the CBT condition, suggesting that for some participants, these barriers may have been enough to warrant discontinuation of therapy. These findings suggest that further treatment adaptations to simplify and reduce the cognitive load of the cognitive therapy component are necessary, and we are currently piloting the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a refined approach.

Some meta-analytic research has found little evidence for outcome differences between bona fide psychosocial treatments.15,49 Thorn and Burns (2011) suggest that if seemingly different treatments for chronic pain have equitable outcomes, then it is plausible that they do so because of common factors of therapy efficacy.41 A key underlying commonality across psychotherapies is establishing rapport and a sound therapeutic relationship between patient and therapist.12 Participants across both conditions frequently commented on the importance of these factors in relation to their own experiences of treatment, thereby supporting the notion that there are common factors associated with perceived therapeutic benefits for CBT and EDU. In the case of a group therapy approach, rapport among the patients themselves also becomes highly relevant and this was reflected in the data with most participants commenting on the significance of group cohesion. Both CBT and EDU participants felt supported by the other group members throughout the learning process. Additionally, prior to the group, participants tended to believe they were the only ones suffering from the ramifications of living with chronic pain and that their thoughts, emotions and behavioral responses were inappropriate in some way. Thus, a powerful insight arose as a function of the group in that many participants came to understand that they weren’t alone in their situation. It is possible that common factors and treatment facilitators (such as flip charts, process check forms, notebooks etc.) help to build a therapeutic foundation from which patient integration of the procedural elements of treatment occurs, such that cognitive change processes may then ensue.

On the surface, it appeared that both CBT and EDU similarly influenced more specific change process factors as participants in both conditions commented on how the respective program engendered shifts in terms of coping skills pertaining to pain. However, it is important to note that while some EDU participants did report increased self-efficacy, pain acceptance, and use of distraction strategies as a consequence of treatment, the prevalence of these statements was much higher among CBT participants. Furthermore, the general lack of distinct subthemes among EDU participants’ comments suggests the possibility that these skills were not as well integrated or as strongly assimilated into their cognitive schema as they were for CBT participants. The distraction process theme clearly illustrated this proposition. In the context of pain, distraction (by definition) implies a voluntary or involuntary shift in attention away from pain, and constitutes a commonly used coping strategy.31 While participants in both conditions reported using behaviors and activities to take their mind off pain, only CBT participants noted an ability to mentally “shift gears” and redirect their thought processes away from pain. This finding may be associated with another important process factor emerging uniquely from the CBT data pertaining to re-engagement in life activities. CBT participants frequently commented that since the group they were more likely to persevere and continue activities they found enjoyable (despite being in pain), and also that they were returning to social activities they had engaged in prior to the onset of chronic pain. These findings suggest CBT uniquely influenced participants’ appraisals such that they might respond more positively to their situation and believe they can cope and continue to live life with chronic pain.

Overall, it appears that within this rural sample, primarily composed of individuals with low-educational attainment, the information presented in the EDU condition was new, and it allowed participants to gain a better understanding of their chronic pain condition. However, CBT more consistently produced cognitive and behavioral shifts identified by the patients as clinically meaningful. Additionally, results suggest that while common factors are powerful in and of themselves, unique, and specific factors of therapy consistent with the theoretical orientation of CBT are instrumental in patient improvement. A wealth of quantitative research has found that improvements in self-efficacy and pain acceptance are associated with positive pain-related outcomes.e.g.,18,19,20,27,43,45 Given that the current results suggest CBT was more effective and efficient in eliciting changes in these cognitive constructs, it seems CBT may offer benefit above and beyond chronic pain treatments with a purely educative theoretical framework. Gaining understanding (from the patients’ perspective) of the most relevant issues pertaining to treatment is exceptionally important. The data gleaned from the current study provides critical information that may be used to guide future treatment adaptations such that the protocol may be refined to meet the unique needs of low-literacy populations. In this regard, qualitative methods have the potential to provide much richer data than do quantitative methodologies. Continued development and evaluation of patient-centered approaches for use within unique and underserved chronic pain populations seems particularly salient in light of the currently pervasive health, treatment and ethnicity disparities.

Limitations

The target population for this study was rural, minority, low-SES chronic pain patients; these demographics have been shown to represent individuals who are the most vulnerable and undertreated.e.g.,1,5,6,10,13,16,28,35,40 Thus, given that the current sample was drawn from an exemplar underserved population, the results are likely not generalizable to other groups. Additionally, the sample was predominantly middle-aged and female; this is consistent with epidemiological data which indicates chronic pain prevalence is highest among these groups.2,3,46,47 However, it is possible that males and older adults for example may report a different pattern of experiences in relation to participation in a psychosocial intervention for chronic pain. While the lack of ability to generalize our findings to other populations is a limitation, given the historical nature of qualitative studies (i.e., small sample size), lack of generalizability is to be somewhat expected. Future qualitative research with more diverse samples is necessary.

Conclusion

In the last several decades, great strides have been made in the development and conceptualization of biopsychosocial treatments for chronic pain. Diagnostic and assessment methodologies have been clarified and biopsychosocial interventions have been successfully applied. Despite these advances, many patients continue to suffer from persistent pain and associated pain-related concomitants. This is the first study to utilize qualitative methodology within the RCT framework to explore and compare common and specific factors associated with biopsychosocial treatments for chronic pain and thereby paves the way for a new and exciting avenue of comparative efficacy research.

Figure 2.

EDU thematic map depicting procedural elements

Figure 3.

CBT thematic map depicting change processes

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the patients and medical staff that made this research possible. The authors would also like to acknowledge Chalanda Cabbil, Kelly Sweeney, Dana McDonald, Susan Gaskins, and Melissa Kuhajda for their earlier contributions to this research project. Special thanks also to Peggy Linhorst for her transcriptions of the audio recordings.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research and the National Institute of Mental Health, NR010112.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors have no other conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.All AC, Fried JH, Wallace DC. Quality of life, chronic pain, and issues for health care professionals in rural communities. Online J Rural Nurs Health Care. 2000;1:19–34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson HI, Ejlertsson G, Leden I, Rosenberg C. Chronic Pain in a Geographically Defined General Population: Studies of Differences in Age, Gender, Social Class, and Pain Localization. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:174–182. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brattberg G, Thorslund M, Wikman A. The prevalence of pain in a general population. The results of a postal survey in a county of Sweden. Pain. 1989;37:215–22. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chibnall JT, Tait RC, Andresen EM, Hadler NM. Race and socioeconomic differences in post-settlement outcomes for African American and Caucasian Workers’ Compensation claimants with low back injuries. Pain. 2005;114:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day MA, Thorn BE. The relationship of demographic and psychosocial variables to pain-related outcomes in a rural chronic pain population. Pain. 2010;151:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eccleston C, Palermo TM, Williams ACD, Lewandowski A, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003968.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehde D, Jensen M, Engel J, Hanley M, Raichle K, Osborne T. Education Intervention Therapist Manual: Project II: Role of Catastrophizing in Chronic Pain. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynt W. Rural poverty in America. Natl Forum. 1996;76:32–35. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallo L, Matthews K. Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: Do negative emotions play a role? Psychol Bull. 2003;129:10–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldfried MR. Toward the delineation of therapeutic change principles. Am Psychol. 1980;35:991–999. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.35.11.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman PK, Meier BP, Council JR. A comparison of chronic pain between an urban and rural population. J Community Health Nurs. 2002;19:213–224. doi: 10.1207/S15327655JCHN1904_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holstein JA, Gubrium JF. Active interviewing. In: Silverman D, editor. Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice. Sage; London: 1997. pp. 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imel ZE, Wampold BE, Miller SD, Fleming RR. Distinctions without a difference: Direct comparisons of psychotherapies for alcohol use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:533–543. doi: 10.1037/a0013171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen L, Findeis J, Hsu W, Schachter J. Slipping into and out of underemployment: Another disadvantage for non-metropolitan workers? Rural Soc. 1999;64:417–438. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keefe FJ, Abernethy AP, Campbell LC. Psychological approaches to understanding and treating disease-related pain. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:601–630. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Baucom D, Salley A. Spouse-assisted coping skills training in the management of osteoarthritic knee pain. Arthritis Care & Research. 1996;9:279–291. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199608)9:4<279::aid-anr1790090413>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Baucom D, Salley A, Robinson E, Timmons K, Beaupre P, Weisberg J, Helms M. Spouse-assisted coping skills training in the management of knee pain in osteoarthritis: Long-term followup results. Arthritis Care & Research. 1999;12:101–111. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)12:2<101::aid-art5>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keefe FJ, Rumble ME, Scipio CD, Giordano LA, Perri LM. Psychological Aspects of Persistent Pain: Current State of the Science. J Pain. 2004;5:195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.02.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kington RS, Smith JP. Socioeconomic status and racial and ethnic differences in functional status associated with chronic diseases. A J Public Health. 1997;87:805–810. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koyama T, McHaffie JG, Laurienti PJ, Coghill RC. The subjective experience of pain: Where expectations become reality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:12950–12955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408576102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhajda MC, Thorn BE, Gaskins SW, Day MA, Cabbil CM. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for chronic pain management: Adapted treatment manual for use with patients with Limited Literacy. Published online with permission from Guilford Publications; http://psychology.ua.edu/people/faculty/bthorn/documents/TherapistManual-Literacy-AdaptedCognitive-BehavioralTreatmentforPatientswithChronicPain.doc.

- 24.Kupers R, Faymonville ME, Laureys S. The cognitive modulation of pain: hypnosis and placebo-induced analgesia. Boundaries of Consciousness. Neurobiology and Neuropathology. 2005;150:251. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lackner JA, Morley S, Dowzer C, Mesmer C, Hamilton S. Psychological treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:1100–1113. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lethbridge-Cejku M, Schiller JS, Bernadel L. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey 2002. Vital & Health Statistics. 2004;10:1–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Litt MD, Shafer DM, Kreutzer DL. Brief cognitive-behavioral treatment for TMD pain: Long-term outcomes and moderators of treatment. Pain. 2010;151:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayberry RM, Mili F, Ofili E. Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Med Care Res Review. 2000;57:108–145. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McIlvane JM. Disentangling the effects of race and SES on arthritis-related symptoms, coping, and well-being in African American and White women. Aging & Mental Health. 2007;11:556–569. doi: 10.1080/13607860601086520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miech RA, Shanahan MJ. Socioeconomic status and depression over the life course. J Health and Soc Behav. 2000;41:162–176. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miron D, Duncan GH, Bushnell MC. Effects of attention on the intensity and unpleasantness of thermal pain. Pain. 1989;39:345–352. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999;80:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moseley GL. Evidence for a direct relationship between cognitive and physical change during an education intervention in people with chronic low back pain. European J Pain. 2004;8:39–45. doi: 10.1016/S1090-3801(03)00063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moseley GL. Physiotherapy is effective for chronic low back pain. A randomised controlled trial. Aus J Physioth. 2002;48:297–302. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen M, Ugarte C, Fuller I, Haas G, Portnenoy R. Access to care for chronic pain: racial and ethnic differences. J Pain. 2005;6:301–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ospina M, Harstall C. In: Prevalence of chronic pain: an overview. Edmonton AB, editor. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, Health Technology Assessment; 2002. Report No. 28. Prepared for the. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ostelo RW. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Library. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ploghaus A, Tracey I, Gati JS, Clare S, Menon RS, Matthews PM, Rawlins JNP. Dissociating pain from its anticipation in the human brain. Science. 1999;284:1979–1981. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5422.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. third edition. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Portenoy RK, Ugarte C, Fuller I, Haas G. Population-based survey of pain in the United States: Differences among white, African American, and Hispanic subjects. J Pain. 2004;5:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thorn BE, Burns JW. Common and specific treatment factors in psychosocial pain management: The need for a new research agenda. Pain. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.017. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.017, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thorn BE. Cognitive Therapy for Chronic Pain: A Step-by-Step Approach. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thorn BE, Pence LB, Ward LC, Kilgo G, Clements KL, Cross TH, Davis AM, Tsui PW. A randomized clinical trial of targeted cognitive behavioral treatment to reduce catastrophizing in chronic headache sufferers. J Pain. 2007;8:938–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turner JA, Mancl L, Aaron LA. Brief cognitive-behavioral therapy for temporomandibular disorder pain: Effects on daily electronic outcome and process measures. Pain. 2005;117:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turner JA, Holtzman S, Mancl L. Mediators, moderators, and predictors of therapeutic change in cognitive--behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain. 2007;127:276–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unruh A. Gender variations in clinical pain experience. Pain. 1996;65:123–167. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verhaak PF, Kerssens JJ, Dekker J, Sorbi MJ, Bensing JM. Prevalence of chronic benign pain disorder among adults: a review of the literature. Pain. 1998;77:231–239. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vlaeyen JW, Teeken-Gruben NJ, Goossens ME, Rutten-van Molken Cognitive-educational treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled clinical trial. I. Clinical effects. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1237–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wampold BE, Mondin GW, Moody M, Stitch F, Benson K, Ahn H. A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empirically, “all must have prizes”. Pyschol Bull. 1997;122:203–215. [Google Scholar]

- 50.White SF, Asher MA, Lai SM, Burton DC. Patients’ perceptions of overall function, pain, and appearance after primary posterior instrumentation and fusion for idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 1999;24:1693–1699. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199908150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]