Abstract

Sporulation in Bacillus subtilis is initiated by an asymmetric division generating two cells of different size and fate. During a short interval, the smaller forespore harbors only 30% of the chromosome until the remaining part is translocated across the septum. We demonstrate that moving the gene for ςF, the forespore-specific transcription factor, in the trapped region of the chromosome is sufficient to produce spores in the absence of the essential activators SpoIIAA and SpoIIE. We propose that transient genetic asymmetry is the device that releases SpoIIE phosphatase activity in the forespore and establishes cell specificity.

Keywords: Bacillus subtilis, sporulation, septum, asymmetry, SpollE, ςF

Establishment of cell specificity is a fundamental question in developmental biology that can be addressed by studying primitive differentiation systems such as sporulation in Bacillus subtilis (Errington 1996). In this soil bacterium, starvation induces an asymmetric septation event that leads to the formation of two cells with different fates (Stragier and Losick 1996). The smaller cell (the forespore) eventually matures into a dormant spore that is released into the medium by lysis of the mother cell. Gene expression in the two cells is controlled by the successive appearance of four new ς factors that modify RNA polymerase promoter specificity. The developmental programs of the two cells are tied to each other such that the whole cascade ultimately depends on the activation of the first transcription factor, ςF (Losick and Stragier 1992).

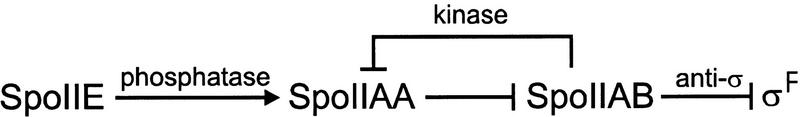

ςF, the product of the spoIIAC gene, is synthesized in the predivisional cell together with the two regulatory proteins SpoIIAA and SpoIIAB. As shown in Figure 1, ςF is held in inactive form by association with the anti-ς factor SpoIIAB (Duncan and Losick 1993; Min et al. 1993). This interaction is disrupted by the SpoIIAA protein after polar septation has occurred and exclusively in the forespore (Diederich et al. 1994; Duncan et al. 1996). SpoIIAA is itself inactivated by phosphorylation by the SpoIIAB protein acting as a kinase (Min et al. 1993), whereas active SpoIIAA is regenerated by the SpoIIE phosphatase (Duncan et al. 1995). Because SpoIIE is also synthesized in the predivisional cell, the establishment of forespore genetic identity relies on the mechanisms delaying SpoIIE-mediated ςF activation until after septation and restricting this activation to the forespore.

Figure 1.

The ςF regulatory pathway. ςF is unable to interact with core RNA polymerase when bound to SpoIIAB, in the predivisional cell and in the mother cell (Duncan and Losick 1993; Min et al. 1993). SpoIIAB can release ςF by binding SpoIIAA in the forespore (Diederich et al. 1994; Duncan et al. 1996).SpoIIAA cannot bind SpoIIAB when phosphorylated by SpoIIAB acting as a kinase (Min et al. 1993). Active SpoIIAA is regenerated by the SpoIIE phosphatase (Duncan et al. 1995) in the forespore (Lewis et al. 1996). Arrows indicate activation, and T-headed arrows indicate inhibition.

It has been proposed that accumulation of dephosphorylated SpoIIAA in the forespore is a consequence of the concentration bias between the SpoIIE phosphatase and the SpoIIAB kinase created by the targeting of SpoIIE to the sporulation septum (Arigoni et al. 1995; Duncan et al. 1995). Additional observations have led to the suggestion that SpoIIE is sequestered on the forespore side of the septum (Wu et al. 1998) or, alternatively, that a putative inhibitor of SpoIIE is excluded from the forespore (Arigoni et al. 1999).

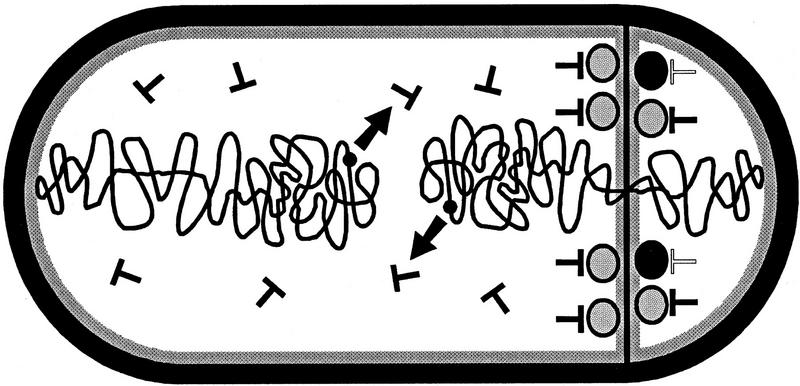

Interestingly, the asymmetric cell division occurring at the beginning of the sporulation process in B. subtilis is accompanied by a transient genetic asymmetry. Because of the extended structure of the DNA in the predivisional cell, the sporulation septum bisects one of the two chromosomes and only about 30% of the genetic material is initially trapped into the forespore compartment (Fig. 2A). The remaining part of the chromosome is transferred into the forespore by a process requiring the SpoIIIE DNA translocase located at the center of the septum (Wu et al. 1995; Wu and Errington 1997). A fixed region of the chromosome, the 30% surrounding the replication origin (Fig. 2B), is always enclosed in the forespore (Wu and Errington 1998) and constitutes its sole genetic material for an interval estimated to 10–15 min (Pogliano et al. 1997). We wondered whether this brief genetic difference between the two cells could be involved in establishing forespore specificity. To address this question, we designed artificial conditions to see whether this transient gene asymmetry could be sufficient to trigger cell differentiation.

Figure 2.

(A) Forespore chromosome partitioning (Wu et al. 1995; Wu and Errington 1997). The two chromosomes issued from the last round of replication are in an extended structure in the predivisional cell (top). A septum is laid down close to one pole and bisects one of the chromosomes, creating transient gene asymmetry (middle). The remaining part of the chromosome is then translocated across the septum into the forespore (bottom). (B) Map of the chromosome indicating the approximate borders (dotted lines) of the region surrounding the replication origin (oriC) initially trapped in the forespore (Wu and Errington 1998). The positions of the spoIIA and spoIIE loci are indicated.

Results

Activating ςF without SpoIIAA

The three proteins SpoIIAA, SpoIIAB, and ςF are encoded by the spoIIA operon located at 209° on the 360° genetic map of B. subtilis, far from the replication origin located at 0° (Fig. 2B). Because of the physical interactions between these proteins (Fig. 1), they have to be synthesized in stoichiometric amounts to ensure normal regulation of ςF activity. We reasoned that moving spoIIAC, the gene encoding ςF, to the region of the chromosome initially trapped in the forespore, and leaving spoIIAB at its normal location, would allow transient accumulation of ςF in the forespore while synthesis of new SpoIIAB molecules would be confined to the mother cell. Then, if the asymmetric distribution of the forespore chromosome lasts long enough, the imbalance generated in favor of ςF in the forespore could be such that some of the ςF molecules would escape inhibition by SpoIIAB, without requiring SpoIIAA counteracting SpoIIAB.

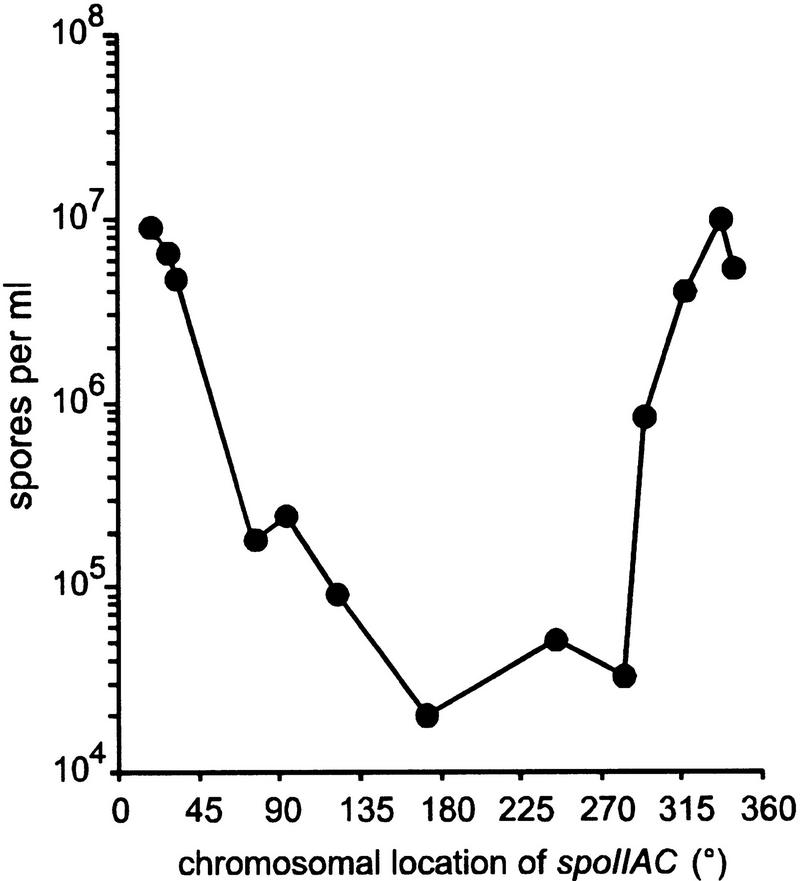

A series of strains was constructed in which the spoIIAA gene was inactivated by an in-frame deletion, the spoIIAC gene at the spoIIA locus was disrupted, and the spoIIAC gene under the control of the spoIIA promoter was integrated at various locations on the chromosome, mostly through insertion into a Tn917 transposon, as detailed in Materials and Methods. (Ectopic expression of spoIIAC at all loci appeared normal as judged from complementation of the spoIIAC defect of an otherwise wild-type strain). These strains were grown in sporulation medium, and the number of heat-resistant spores produced was determined. A typical series of results is shown in Figure 3. Whereas inactivation of the spoIIAA locus normally creates a complete block in sporulation (<10 spores/ml instead of 2 × 108–5 × 108 in wild-type cells), a very high number of spores (5 × 106– 107 spores/ml) was observed when the spoIIAC gene was located in the 300°–40° interval. This location fits very well with the region that is trapped in the forespore by asymmetric septation (Wu and Errington 1998), and it suggests that the bypass of the SpoIIAA product for ςF activation is due to the transient accumulation of ςF in the forespore in the absence of the spoIIAB gene, resulting in titration of SpoIIAB by ςF. A much lower but still significant amount of spores (104–105 spores/ml) was observed when spoIIAC was located outside of the 300°–40° interval and, therefore, was assumed to be always present in the same cell as spoIIAB. It might be that physically separating the spoIIAB and spoIIAC genes creates a slight imbalance in favor of ςF, either because of higher synthesis of ςF from the altered spoIIAC gene, or because interaction between SpoIIAB and ςF is more efficient when they are synthesized in the immediate vicinity of each other. Alternatively, short segments of the chromosome located outside of the 30% surrounding the replication origin might occasionally be trapped in the forespore during asymmetric septation and the spoIIAC gene segregated away from spoIIAB.

Figure 3.

Spore formation in the absence of SpoIIAA. A series of strains deleted for spoIIAA, and in which spoIIAC was inactivated at the spoIIA locus and inserted at various locations around the chromosome, were grown in sporulation medium for about 30 hr, and heat-resistant spore numbers were determined. The experiment was done at least twice and, for most strains, three times. Very similar results were obtained in each case. A typical series of results is shown.

The progress of sporulation in one of the strains in which SpoIIAA could be efficiently bypassed was studied further by electron microscopy. As reported in Table 1, about half of the bacteria harvested 4 hr after the entry into stationary phase showed the classic disporic phenotype of spoIIAA mutants, with forespores at both ends of the cells. However, 14% of the cells had reached the morphological stage where the forespore is fully engulfed by the mother cell, a step that is absolutely dependent on ςF (Londoño-Vallejo et al. 1997). This suggests that the efficiency of ςF activation might be even higher than indicated by the 2%–4% of mature heat-resistant spores produced by that strain and that, in many cells, sporulation aborts later because of some unidentified deficiency, possibly by unregulated SpoIIAB interfering with ςG, the late forespore ς factor (Kellner et al. 1996). Direct measurement of ςF activity indicated that the rate of accumulation of β-galactosidase synthesized under the control of a ςF-dependent promoter was about 10% of that observed in wild type, a result that did not depend on the location of the reporter gene on the chromosome (data not shown).

Table 1.

Phenotypic classes scored by electron microscopy

| Morphological characteristics

|

Wild type

|

SpoIIAA bypassa

|

SpoIIE bypassb

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No septum | 25 | 14 | 29 |

| Central septum | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| Thin septum | 8 | 20 | 13 |

| Thick septum | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Multiple septa | 0 | 3 | 9 |

| Disporics | 0 | 49 | 6 |

| Engulfed forespores | 64 | 14 | 17 |

Values are expressed as percentage of each phenotype in cells harvested 4 hr after the onset of sporulation.

The strain contains an in-frame deletion in spoIIAA and an erythromycin resistance cassette in spoIIAC, whereas an intact copy of spoIIAC is inserted at 317° through the zii83∷Tn917 transposon.

The strain contains a phleomycin resistance cassette in spoIIE and an erythromycin resistance cassette in spoIIAC, whereas an intact copy of spoIIAC is inserted at 317° through the zii83∷Tn917 transposon.

Activating ςF without SpoIIE

The SpoIIE protein has been described as a bifunctional protein, acting as a phosphatase on phosphorylated SpoIIAA molecules, as well as being required for maturation of the sporulation septum (Barák and Youngman 1996; Feucht et al. 1996). Null mutations in spoIIE completely prevent spore formation. Because the presence of spoIIAC in the replication origin region allowed a significant number of cells to bypass the normal regulatory pathway of ςF activation and to sporulate without production of dephosphorylated SpoIIAA, we checked the effect of the absence of SpoIIE in these conditions. Strains were constructed in which the spoIIE and spoIIAC loci were disrupted, and the spoIIAC gene under the control of the spoIIA promoter was introduced at various locations on the chromosome. We found that the presence of the spoIIAC gene at 18°, 33°, and 317° allowed spore production without SpoIIE in the same range as in strains bypassing SpoIIAA (7 × 106–2 × 107 spores/ml). Moreover, electron microscopy analysis revealed that, in addition to the 30% of cells showing the classical spoIIE null phenotype (thick septa and multiple septa), 17% of the cells had completed engulfment 4 hr after the entry into stationary phase (Table 1), suggesting that SpoIIE can be as efficiently bypassed as SpoIIAA for spore morphogenesis. Finally, introduction of a spoIIE mutation in strains engineered to bypass SpoIIAA and harboring the spoIIAC gene at 28° or 337° did not alter significantly their efficiency of sporulation (about 1 × 107 spores/ml).

We took advantage of the possibility to bypass SpoIIE for ςF activation to investigate more about the molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon. The spoIIAB and spoIIAC genes of a spoIIE null mutant were both disrupted and moved to separate positions on the chromosome. The spoIIAB gene, under the control of the spoIIA promoter and together with the spoIIAA gene, was inserted at 324°, a chromosomal location that is trapped in the forespore during asymmetric septation. The spoIIAC gene, under the control of the spoIIA promoter, was introduced at positions that are segregated either inside (33° or 317°) or outside (172° or 194°) the forespore. None of these strains produced any spores, indicating that, for bypassing the regulatory pathway activating ςF, separating the spoIIAB and spoIIAC genes is not sufficient and that spoIIAB has to be initially located outside the forespore.

The identity of the chromosomal segment trapped in the forespore (Fig. 2B) has been described to be dependent on the product of the spo0J gene that would anchor the chromosome to the cell pole before division (Sharpe and Errington 1996). Therefore, we inactivated the spo0J locus in the spoIIE strains harboring spoIIAB at 324° and spoIIAC at 172° or 194°. We expected that in a significant number of cells, the spoIIAC gene would be trapped in the forespore whereas the remote spoIIAB gene would remain in the mother cell and that heat-resistant spores would be produced. However, this was not the case and neither strain was able to produce a single spore, suggesting that the chromosomal region around 324° is always trapped in the forespore, even in the absence of the Spo0J protein. It is unlikely that this complete absence of spore production (as compared to the 5 × 106–107 spores/ml observed in the previous set of experiments) is due to an abnormally high level of expression of spoIIAB at 324°.

Discussion

The importance of transient gene asymmetry

The regulatory pathway controlling ςF activity involves three proteins, SpoIIE, SpoIIAA, and SpoIIAB, and is intimately tied to completion of septum formation. Its complexity seems to be a prerequisite for preventing ςF activation in the predivisional cell, which would block further progression of the sporulation process (Coppolecchia et al. 1991), as well as for relaxing ςF inhibition exclusively in the forespore. Here, we report that most of this pathway can be partially bypassed just by displacing the gene encoding ςF on the chromosome and that the SpoIIAB protein may be sufficient to control ςF activity such that sporulation occurs with 2%–4% of wild-type efficiency. Because a large portion of the chromosome is segregated into the forespore only after septation, unequal division of the sporulating cell creates a transient gene asymmetry that lasts long enough to establish forespore genetic specificity, providing that the genes encoding ςF and its SpoIIAB inhibitor are located in appropriate regions of the chromosome.

An unexpected result of these experiments is that there is no significant difference in sporulation efficiency between cells engineered to bypass SpoIIAA, the antagonist of SpoIIAB, and cells engineered to bypass SpoIIE, the protein activating SpoIIAA. This suggests that the only essential role of SpoIIE in sporulation is to allow formation of active, dephosphorylated SpoIIAA, although it has been described as also being required for septum formation and maturation (Barák and Youngman 1996; Feucht et al. 1996). Electron microscopy studies of bacteria bypassing SpoIIE have confirmed the presence of many cells with abnormally thick septa or multiple septa (which become a prominent feature in cells harvested at later times), whereas bacteria bypassing SpoIIAA showed only thin septa. However, because 30% of the cells bypassing SpoIIE contained either a thin septum or a fully engulfed forespore (Table 1), it appears that the involvement of SpoIIE in septum maturation is indirect and accessory.

Another side result of these experiments is that the Spo0J protein is not involved in specifying the orientation of the chromosome and thus defining the region that is initially trapped in the forespore, as proposed previously (Sharpe and Errington 1996). Because of the remarkable sensitivity of the sporulation assay (six orders of magnitude in our bypass experiments), it can be concluded that the region surrounding 324° is always on the forespore side after asymmetric septation, even in the absence of Spo0J. However, if Spo0J is involved in chromosome organization (Lin and Grossman 1998), its absence might allow additional short DNA segments located outside of the 30% surrounding the replication origin to be trapped in the forespore at a significant frequency, as suggested previously (Webb et al. 1997). Indeed, the main evidence for a centromere-like function of Spo0J was the demonstration that the absence of Spo0J allows some expression of a ςF-dependent reporter gene located in a region of the chromosome normally excluded from the forespore in a strain blocked in the chromosomal translocation process (Sharpe and Errington 1996).

A model for establishment of forespore specificity

The experiments described above indicate that the transient gene asymmetry existing after polar division can create an imbalance between two proteins (in our artificial conditions ςF and SpoIIAB) sufficient to switch on the forespore genetic program in a significant number of cells. We propose that this regulatory device is naturally occurring, acting at the level of the SpoIIE protein. The mechanisms allowing accumulation of dephosphorylated SpoIIAA molecules specifically in the forespore are still a matter of conjecture. The ratio between the two enzymes acting on SpoIIAA in opposite directions, the SpoIIAB kinase and the SpoIIE phosphatase, has been suggested to play a crucial role (Duncan et al. 1995). Therefore, it is intriguing that the genes encoding these two proteins are located at such chromosomal positions (Fig. 2B) that asymmetric septation will effectively create a bias in favor of SpoIIE in the forespore. However, displacing the spoIIE gene at 283°, outside of the region trapped in the forespore, has no effect on sporulation efficiency (F. Arigoni and N. Frandsen, unpubl.), suggesting that additional synthesis of SpoIIE in the forespore is not important for activating ςF.

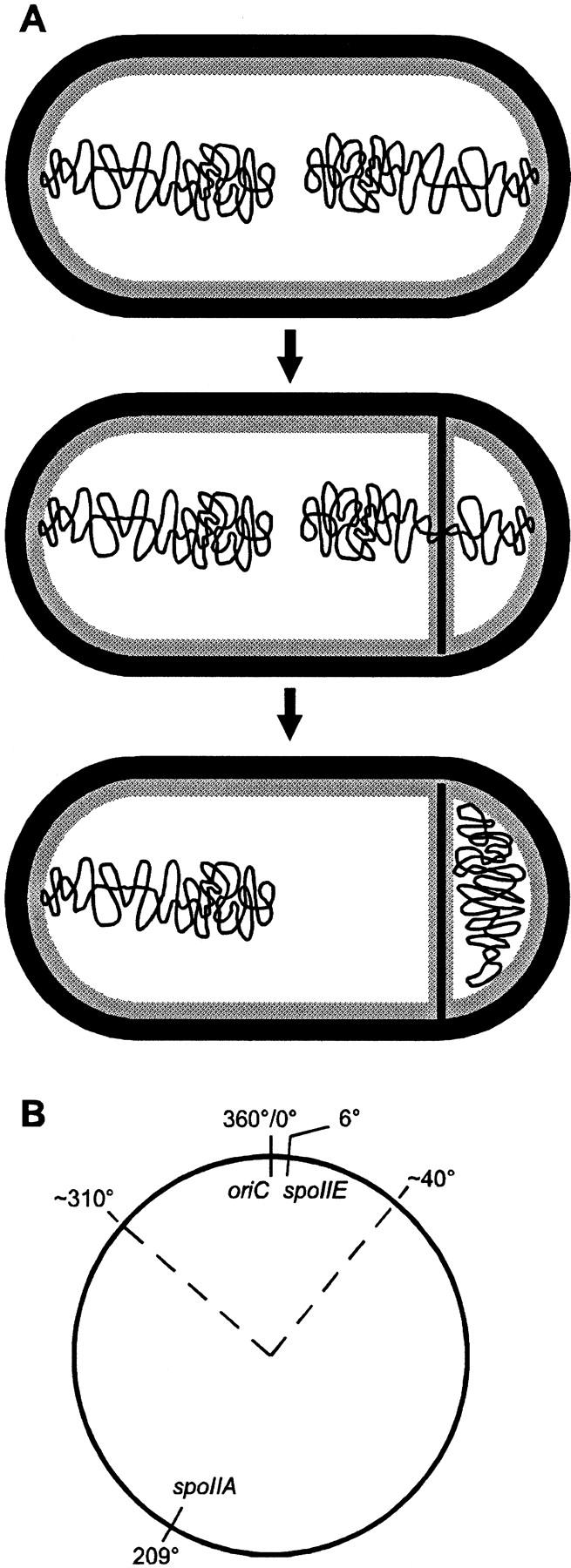

It has been proposed recently that SpoIIE phosphatase activity is controlled by an inhibitory molecule that is specifically excluded from the forespore (Arigoni et al. 1999). Transient gene asymmetry could be the basis of this exclusion if the SpoIIE inhibitor is an unstable protein encoded by a gene located outside of the chromosome interval trapped in the forespore (Fig. 4). In that case, the imbalance between the two partners would result from depletion of the inhibitor in the forespore (instead of accumulation of its target protein as in our experiments above), whereas SpoIIE would be kept inactive in the mother cell by continued synthesis of its inhibitor. Escaping inhibition would allow some SpoIIE molecules (Fig. 4) to produce dephosphorylated SpoIIAA and ultimately to activate ςF. Because of the catalytic activity of SpoIIE, a partial and transitory release of its inhibition could be sufficient to induce an irreversible switch in forespore gene expression before the entry of the remaining part of the forespore chromosome. Other models are possible but our results suggest that the transient genetic asymmetry resulting from the polar position of the sporulation septum could be the signal triggering the forespore fate.

Figure 4.

How transient gene asymmetry could activate SpoIIE. The SpoIIE molecules (ovoids) are targeted to the sporulation septum, which bisects one of the two chromosomes (wiggly lines). The SpoIIE molecules are locked in inactive form (shaded ovoids) by interaction with an inhibitor (T-shaped, solid) encoded by a gene (solid circles and arrows) located on the mother-cell side (left) of the septum. In the forespore (right) the inhibitor is not neosynthesized and disappears (T-shaped, open), switching some SpoIIE molecules to an active form (solid ovoids).

Material and methods

Bacterial strains

All the results reported in this paper were obtained with derivatives of the sporulation-proficient strain JH642 (trpC2 pheA1). The in-frame deletion in spoIIAA originates from strain IJC5Adel1 kindly provided by M. Yudkin (Min et al. 1993). It was transferred into the JH642 background by linkage with a kanamycin-resistance marker inserted between the spoIIA and spoVA operons (F. Arigoni, unpubl.). The spoIIAC null mutant was created by insertion of an erythromycin-resistance marker at codon 127 of spoIIAC. The spoIIAB spoIIAC double mutant was created by insertion of an erythromycin-resistance marker between codon 87 of spoIIAB and codon 127 of spoIIAC. The spoIIE null mutant tagged with a phleomycin-resistance marker has been described (Arigoni et al. 1999). The spo0J mutant was constructed by A.-M. Guérout-Fleury by insertion of a kanamycin-resistance marker between codon 21 of soj and codon 190 of spo0J [inactivation of the adjacent soj gene suppresses the early sporulation blockage observed in the absence of Spo0J (Ireton et al. 1994)]. The sspE–2G–lacZ fusion used as a reporter of ςF activity has been described (Shazand et al. 1995) and was inserted at the amyE or the thrC locus (Guérout-Fleury et al. 1996) through linkage to a tetracycline-resistance marker. Conditions of selection for antibiotic resistance and of sporulation by exhaustion of Difco nutrient broth medium have been described (Arigoni et al. 1999).

Ectopic expression of segments of the spoIIA operon

The proximal region of the spoIIA operon, from the ScaI site located 165 bp upstream of the spoIIA transcription start to the PvuII site located at codon 13 of spoIIAC, was inserted in the nonessential ywlB gene by linkage to a spectinomycin-resistance marker, allowing expression of spoIIAA and spoIIAB from position 324° on the chromosome. The in-frame deletion overlapping spoIIAA and spoIIAB and placing spoIIAC alone under the control of the spoIIA promoter has been described (Shazand et al. 1995). This construct was linked to a chloramphenicol-resistance marker (upstream and diverging from spoIIAC) and to the strong transcription terminators t1t2 from rrnB (downstream from and converging toward spoIIAC) and inserted between positions 1093 and 2507 of Tn917, spoIIAC being in the opposite orientation of the inactivated erythromycin-resistance marker. It was introduced at various locations on the chromosome by transformation of a collection of strains, each harboring a specific Tn917 insertion. The following strains (all from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center) were used (location of the Tn917 insertion is indicated): 1A686 (zae-86, 18°), 1A724 (zba-88, 33°), 1A628 (zbj-82, 75°), 1A630 (zce-82, 94°), 1A631 (zdd-85, 123°), 1A635 (zej-82, 172°), 1A637 (zff-82, 194°), 1A639 (zgi-83, 245°), 1A643 (zib-82, 294°), 1A644 (zii-83, 317°), 1A732 (zjd-89, 337°), 1A645 (zjf-85, 345°). In six cases, the left border of the Tn917 insertion was amplified by reverse PCR and sequenced, indicating differences of <7° with the genetically determined chromosomal positions of the Tn917 insertions (Youngman 1993). The same spoIIAC fragment was also introduced at the amyE (28°) and thrC (283°) loci (Guérout-Fleury et al. 1996).

Ultrastructural studies

Samples for electron microscopy were processed as described previously (Arigoni et al. 1999). Stained thin sections were examined and photographed on a JOEL-100 CX electron microscope. For quantification of morphological classes, at least 100 complete longitudinal sections were scored from random fields for each sample.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Arigoni, A.-M. Guérout-Fleury, M. Yudkin, and D. Zeigler from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center for their gift of strains, and Jozef Kriŝtín for use of his electron microscope. N.F. was a recipient of an E.E.C. postdoctoral fellowship (Human Capital and Mobility Programme). This work was supported by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) (grant UPR 9073 to P.S.) and by Slovak Academy of Sciences (grant 5025 to I.B.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL stragier@ibpc.fr; FAX (33) 1 40 46 83 31.

References

- Arigoni, F., A.-M. Guérout-Fleury, I. Barák, and P. Stragier. 1999. The SpoIIE phosphatase, the sporulation septum, and the establishment of forespore-specific transcription in Bacillus subtilis: A reassessment. Mol. Microbiol. (In press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Arigoni F, Pogliano K, Webb CD, Stragier P, Losick R. Localization of protein implicated in establishment of cell type to sites of asymmetric division. Science. 1995;270:637–640. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barák I, Youngman P. SpoIIE mutants of Bacillus subtilis comprise two distinct phenotypic classes consistent with a dual functional role for the SpoIIE protein. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4984–4989. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4984-4989.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppolecchia R, DeGrazia H, Moran CP., Jr Deletion of spoIIAB blocks endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis at an early stage. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6678–6685. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.6678-6685.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederich B, Wilkinson JF, Magnin T, Najafi SMA, Errington J, Yudkin MD. Role of interactions between SpoIIAA and SpoIIAB in regulating cell-specific transcription factor ςF of Bacillus subtilis. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:2653–2663. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan L, Losick R. SpoIIAB is an anti-ς factor that binds to and inhibits transcription by regulatory protein ςF from Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:2325–2329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan L, Alper S, Arigoni F, Losick R, Stragier P. Activation of cell-specific transcription by a serine phosphatase at the site of asymmetric division. Science. 1995;270:641–644. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan L, Alper S, Losick R. SpoIIAA governs the release of the cell type-specific transcription factor ςF from anti-sigma factor SpoIIAB. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:147–164. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errington J. Determination of cell fate in Bacillus subtilis. Trends Genet. 1996;12:31–34. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)81386-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feucht A, Magnin T, Yudkin MD, Errington J. Bifunctional protein required for asymmetric cell division and cell-specific transcription in Bacillus subtilis. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:794–803. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.7.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guérout-Fleury A-M, Frandsen N, Stragier P. Plasmids for ectopic integration in Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1996;180:57–61. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00404-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireton K, Gunther NW, IV, Grossman AD. spo0J is required for normal chromosome segregation as well as the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5320–5329. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5320-5329.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellner EM, Decatur A, Moran CP., Jr Two-stage regulation of an anti-sigma factor determines developmental fate during bacterial endospore formation. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:913–924. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.461408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis PJ, Magnin T, Errington J. Compartmentalized distribution of the proteins controlling the prespore-specific transcription factor ςF of Bacillus subtilis. Genes to Cells. 1996;1:881–894. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.750275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin DC-H, Grossman AD. Identification and characterization of a bacterial chromosome partitioning site. Cell. 1998;92:675–685. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londoño-Vallejo JA, Frehel C, Stragier P. spoIIQ, a forespore-expressed gene required for engulfment in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:29–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3181680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losick R, Stragier P. Crisscross regulation of cell-type specific gene expression during development in Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1992;355:601–604. doi: 10.1038/355601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min K-T, Hilditch CM, Diederich B, Errington J, Yudkin MD. ςF, the first compartment specific transcription factor of Bacillus subtilis, is regulated by an anti-sigma factor which is also a protein kinase. Cell. 1993;74:735–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90520-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogliano K, Hofmeister AEM, Losick R. Disappearance of the ςE transcription factor from the forespore and the SpoIIE phosphatase from the mother cell contributes to establishment of cell specific gene expression during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3331–3341. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3331-3341.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe ME, Errington J. The Bacillus subtilis soj-spo0J locus is required for a centromere-like function involved in prespore chromosome partitioning. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:501–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shazand K, Frandsen N, Stragier P. Cell-type specificity during development in Bacillus subtilis: The molecular and morphological requirements for ςE activation. EMBO J. 1995;14:1439–1445. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stragier P, Losick R. Molecular genetics of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:297–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb CD, Teleman A, Gordon S, Straight A, Belmont A, Lin DC-H, Grossman AD, Wright A, Losick R. Bipolar localization of the replication origin regions of chromosomes in vegetative and sporulating cells of B. subtilis. Cell. 1997;88:667–674. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81909-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LJ, Errington J. Septal localization of the SpoIIIE chromosome partitioning protein in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 1997;16:2161–2169. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Use of asymmetric cell division and spoIIIE mutants to probe chromosome orientation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:777–786. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LJ, Lewis PJ, Allmansberger R, Hauser PM, Errington J. A conjugation-like mechanism for prespore chromosome partitioning during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1306–1326. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.11.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LJ, Feucht A, Errington J. Prespore-specific gene expression in Bacillus subtilis is driven by sequestration of SpoIIE phosphatase to the prespore side of the asymmetric septum. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1371–1380. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngman P. Transposons and their applications. In: Sonenshein AL, Hoch J, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other Gram-positive bacteria. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 585–596. [Google Scholar]