Abstract

Objective

We determined the association between clinically significant depressive symptoms, often referred to as depression, and subsequent transitions between no disability, mild disability, severe disability, and death.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

General community in greater New Haven, Connecticut, from March 23, 1998, to December 31, 2008.

Participants

Seven-hundred fifty four persons, aged 70 years or older.

Measurements

Monthly assessments of disability in essential activities of daily living and assessments of depressive symptoms every 18 months using a short-form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Scale for up to 129 months.

Results

Depressed participants were more likely than those who were non-depressed to transition from a state of no disability to mild (HR= 1.52; 95% CI 1.25, 1.85) and severe disability (HR=1.57; 95% CI 1.22, 2.01), and from a state of mild disability to severe disability (HR=1.33; 95% CI 1.06, 1.65); and were less likely to transition from a state of mild disability to no disability (HR=0.69; 95% CI 0.57, 0.85) and from a state of severe disability to no disability (HR=0.50; 95% CI 0.31, 0.79).

Conclusions

Depressive symptoms are associated with transitions into and out of disabled states, and with increased likelihood of transitioning from mild to severe disability. More broadly, our findings underscore the complexity of the relationship between depressive symptoms and disability. Future work is needed to evaluate the likely reciprocal relationship between depression and functional transitions in older persons.

Keywords: Depression, Depressive symptoms, Disability, Prospective studies

OBJECTIVE

Whereas major depression affects 1% to 2% of community-living older persons, 8% to 20% of this population experiences clinically significant depressive symptoms.(1) Often referred to as depressed mood or simply “depression,” clinically significant depressive symptoms can fluctuate over time, with periods of remission and recurrence.(2) Clinically significant depressive symptoms in late life are associated with substantial morbidity and frequent utilization of health services.(3) In addition, depressed older persons are more likely than their non-depressed counterparts to be disabled in essential activities of daily living (ADLs) and to develop the onset of disability.(4, 5)

Like depressive symptoms, disability is often reversible and recurrent,(6) more similar to falls and delirium than to progressive disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, the severity of disability differs across individuals and within the same person over time.(7) The complex nature of disability has been more fully elucidated through recent work demonstrating that older persons frequently experience transitions between states of no, mild, and severe disability.(8) With few exceptions(5, 9) however, prior studies evaluating the relationship between depressive symptoms and disability have not considered the dynamic nature of these conditions; nor have they considered disability as a condition with potentially varying levels of severity, ranging from mild to severe. Consequently, the association between depressive symptoms and transitions into and out of states of mild and severe disability in older persons remains unknown.

The objective of this prospective study was to determine the association between clinically significant depressive symptoms and subsequent functional transitions between states of no disability, mild disability, severe disability, and death among older persons over time. We hypothesized that clinically significant depressive symptoms would have a positive association with transitions into mild and severe disability and death, and a negative association with transitions out of mild and severe disability. To test these hypotheses, we used data from a unique cohort of older persons who had assessments of depressive symptoms every 18 months and monthly assessments of disability for nearly ten years. We performed a rigorous longitudinal analysis of each of the functional transitions according to whether or not participants had clinically significant depressive symptoms. Establishing a relationship between depressive symptoms and meaningful transitions in functional status would help to inform clinical decision-making and may ultimately lead to reductions in the burden of disability among older persons.

METHODS

Sample

Participants were members of the Precipitating Events Project (PEP), a longitudinal study of 754 non-disabled, community-living persons aged 70 years or older.(10) The assembly of the cohort has been described in detail elsewhere.(10) In brief, potential participants were identified from 3,157 age-eligible members of a health plan in New Haven, Connecticut. The primary inclusion criteria were English speaking and requiring no personal assistance with four essential activities of daily living—bathing, dressing, transferring from a chair, and walking across a room. The participation rate was 75.2%.(10) The Human Investigation Committee at Yale University approved the study.

Data collection

Comprehensive home-based assessments were completed at baseline and subsequently at 18-month intervals until each person’s death or through 108 months, while telephone interviews were completed monthly until each person’s death or end of follow-up for up to 129 months, resulting in a median follow-up of 109 months. Deaths were ascertained by review of the local obituaries and/or from an informant during a subsequent telephone interview. Four hundred and five (53.7%) participants died after a median follow-up of 68 months, while 35 (4.6%) dropped out of the study after a median follow-up of 24 months. Data were otherwise available for 99.2% of the 66,425 monthly telephone interviews.

During the baseline assessment, data were collected on demographic characteristics, including age, sex, race, years of education, and living alone. During each of the comprehensive assessments, data were collected on several important clinical factors. Medical comorbidity was ascertained based on a count of up to nine self-reported, physician-diagnosed chronic conditions: hypertension, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes mellitus, arthritis, hip fracture, chronic lung disease, and cancer. Cognitive status was assessed by the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),(11) where MMSE scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores representing better cognitive status. Physical frailty was assessed using a rapid gait test in which participants were instructed to walk a 10-foot (3.048-m) course “as fast as it feels safe and comfortable,” turn around, and walk back. Participants who completed the task in >10 seconds were considered to be physically frail.(12) Physical activity was assessed by the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE), where PASE scores range from 0 to 400.(13) The use of antidepressant medication(s) was ascertained by review of all pill bottles or a medication list. If a list was unavailable, participants were asked to recall medications that they had taken during the prior two weeks. All medications, but not the doses or dosing schedule, were recorded and antidepressant medications were subsequently coded based on the American Hospital Formulary system (AHFS) code 28.16.04. Trazodone and Amitriptyline were not coded as antidepressants because they are commonly used for other indications, including sleep and pain.(14, 15) The amount of missing data for the aforementioned variables was less than 1% in the baseline assessment and less than 5% in all subsequent assessments.

Assessment of depressive symptoms

During each of the comprehensive assessments, the frequency of depressive symptoms in the previous week was assessed with the 11-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression (CES-D) scale.(16) Prior studies of older persons have reported test-retest reliability statistics (i.e., Kappa coefficients) of 0.82 or higher for the shortened version of the CES-D.(17, 18) Scores were transformed using the procedure recommended by Kohout et al. to make it compatible with the full 20-item instrument.(19) Total scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Participants scoring ≥20 were considered as having “clinically significant depressive symptoms” or “depressed.” While a CES-D score of 16 is most commonly used to distinguish between depressed and non-depressed persons in mixed-age samples, a cut point of 20 offers a more stringent approach to the classification of depressed mood among older persons and increases the specificity for identifying major depression according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV (DSM-IV) criteria.(20) Nonetheless, in a secondary analysis, depression was operationalized based on a CES-D score ≥16. Data on depression were complete for 100% of the participants at baseline and 95%, 93%, 91%, 90%, 89%, and 88% of the non-decedents at 18, 36, 54, 72, 90, and 108 months, respectively.

Assessment of disability

Disability in the four essential ADL tasks was assessed during the monthly telephone interviews. Complete details regarding the monthly interviews, including formal tests of reliability and accuracy, have been previously described.(21) Participants who needed help from another person or were unable to complete an ADL were considered disabled in that task. Participants were classified each month as being in one of four states: non-disabled (disabled in 0 of the ADLs), mild disability (disabled in 1 or 2 of the ADLs), severe disability (disabled in 3 or 4 of the ADLs), or death.(22) During the comprehensive assessments, participants also were asked about their ability to eat, groom themselves, and use the toilet without personal assistance. The concordance of assessing severity of disability using 4 ADLs rather than 7 ADLS was high, with weighted kappa values ranging from 0.87 at the 36-month comprehensive assessment to 0.96 at the 72-month comprehensive assessment. Based on a multistate representation of disability,(8) functional transitions occurred in both directions between the no disability, mild disability, and severe disability states and in one direction from each of these three states to death, resulting in nine possible transitions. To illustrate, a non-disabled participant who subsequently experienced two months of severe disability, followed by a month of mild disability, after which she recovered independence, would have had three functional transitions.

Statistical Analysis

We compared the baseline characteristics among participants who were non-depressed and depressed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. We then determined the unadjusted incidence rates for each of the nine transitions per 1000 person-months over the entire follow-up period according to depression status at the 18-month comprehensive assessment preceding the transition. For each incidence rate, we calculated 95% confidence intervals by bootstrapping samples with replacement. One thousand samples were created, and the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles were used to form the confidence intervals. These bootstrap-derived estimates and confidence intervals provide non-parametric estimates of the rates and their dispersion.

To address the small amount of missing data for depressive symptoms and the covariates, missingness was assumed to be random and we used multiple imputation with 50 random draws per missing observation, accounting for the potential correlation among repeated measures.(23) We also used multiple imputation with 50 random draws to address the small amount of missing monthly data on disability. Following recent recommendations for binary longitudinal data,(24) the probability of missingness was imputed based on a GEE logistic regression model; and values for disability (present or absent) for each of the four essential ADLs were imputed for each missing month sequentially from the first month to either the person’s death or the end of follow-up. No values were imputed to individuals after their death date.

We used a competing risk Cox model for recurring events, in which participants are simultaneously at risk for several “competing” outcomes, to evaluate the unadjusted associations between depressive symptoms and each of the nine functional transitions.(25, 26) Using this method, we simultaneously model the associations between depression and nine potential transitions that are grouped into three triplets, where each triplet is a set of competing events. Functional transitions are updated on a monthly basis. For example, participants in the state of severe disability in any given month are simultaneously at risk for transitioning in the next month to a state of no disability, mild disability, or death. Upon entering a new state, with the exception of death, they are at risk for another three potential state transitions. The model calculates the associations based on the amount of time spent in the state preceding transition into another state. Interpretation of the results must therefore consider the aggregate time spent in specific states with and without covariates of interest. Furthermore, this method accounts for the correlation among observations within individuals through the use of robust sandwich variance estimators for standard errors of the coefficients.(27), is fairly robust to the distribution of time to event data, and can be used for non-proportional hazards, which may occur with time-varying covariates.(26) The final multivariable model was adjusted for demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, race, education, and living alone), clinical factors (i.e., number of chronic conditions, cognitive status, physical frailty, and physical activity), and antidepressant medication use across all transitions. With the exception of sex, race, and education, these variables were treated as time-dependent covariates. The p-values for the final multivariable model were adjusted for multiple comparisons assuming a false discovery rate of 5%.(28) These analyses were repeated using a cutpoint of ≥16 on the CES-D.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p-values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

At baseline, 100 (13.3%) participants had clinically significant depressive symptoms and were considered “depressed.” Table 1 provides the baseline characteristics of participants according to their depression status. Differences were observed for all characteristics with the exception of age, race, and living alone. As compared with the non-depressed participants, those who were depressed were more likely to be women, physically frail, and taking an antidepressant medication, and had a higher number of chronic conditions, fewer years of education, and lower MMSE scores.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants According to Depression Status.a

| Characteristic | Non-Depressed (n=654) |

Depressedb (n=100) |

ρ-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean years (SD) | 78.4 (5.2) | 78.6 (5.4) | 0.82 |

| Women, n (%) | 401 (61.3) | 88 (88.0) | <0.001 |

| White, n (%) | 596 (91.3) | 86 (86.0) | 0.10 |

| Education, mean years (SD) | 12.1 (2.9) | 11.1 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Living alone, n (%) | 253 (38.7) | 45 (45.0) | 0.23 |

| Number of chronic conditions, mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.4) | 0.03 |

| Cognitive status, mean (SD)d | 26.9 (2.4) | 26.0 (2.8) | 0.006 |

| Physical frailty, n (%) | 260 (39.8) | 62 (62.0) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity score, mean (SD)e | 93.9 (59.2) | 62.7 (38.5) | <0.001 |

| Antidepressant medication use, n (%) | 41 (6.3) | 17 (17.0) | <0.001 |

Compares characteristics according to participants’ baseline depression status.

Determined using the Center for Epidemiological Studies - Depression Scale; Depressed = score ≥20.

Represents overall associations as determined by chi-square and t-tests. Degrees of freedom = 1 for each of the categorical variables and degrees of freedom = 751 for each of the continuous variables.

Assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

Assessed with the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE).

Table 2 provides the unadjusted incidence rates and 95% confidence intervals for each of the functional transitions over the entire follow-up period according to depression status during the previous comprehensive assessment. Depressed participants had significantly higher unadjusted rates than those who were non-depressed for the transitions from no disability to mild disability and severe disability, and for the transition from mild to severe disability. In contrast, depressed participants had significantly lower unadjusted rates for the transitions from mild disability to no disability, and from severe disability to no disability. The unadjusted incidence rates did not differ between non-depressed and depressed participants for the transitions from any of the three disability states to death.

Table 2.

Unadjusted incidence rates for functional transitions per 1000 person-months.a

| Non-depressed Rate (95% Cl)b |

Depressed Rate (95% Cl)b |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition | |||

| No disability to: | |||

| Mild | 32.2 (29.4, 34.7) | 57.8 (49.7, 65.3) | <0.001 |

| Severe | 6.0 (5.4, 6.6) | 10.5 (8.8, 12.3) | <0.001 |

| Death | 2.1 (1.8, 2.4) | 2.8 (1.9, 3.6) | 0.14 |

| Person-months at risk | 45,593 | 7,684 | |

| Transition | |||

| Mild disability to: | |||

| None | 215.9 (198.5, 234.2) | 140.1 (122.8, 160.1) | <0.001 |

| Severe | 87.7 (78.0, 96.6) | 99.2 (83.6, 114.9) | <0.001 |

| Death | 9.5 (7.5, 11.3) | 8.1 (5.7, 10.7) | 0.99 |

| Person-months at risk | 5,879 | 2,532 | |

| Transition | |||

| Severe disability to: | |||

| None | 39.5 (33.4, 46.2) | 13.7 (9.7, 18.0) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 153.2 (137.2, 173.0) | 124.5 (104.9, 143.4) | 0.50 |

| Death | 37.9 (32.8, 43.8) | 24.7 (20.7, 29.5) | 0.09 |

| Person-months at risk | 2,889 | 1,815 | |

CI=Confidence Interval

The median length of follow-up was 109 months.

The confidence intervals for the unadjusted incidence rates were calculated by bootstrapping samples with replacement and provide non-parametric estimates of the rates and their dispersion.

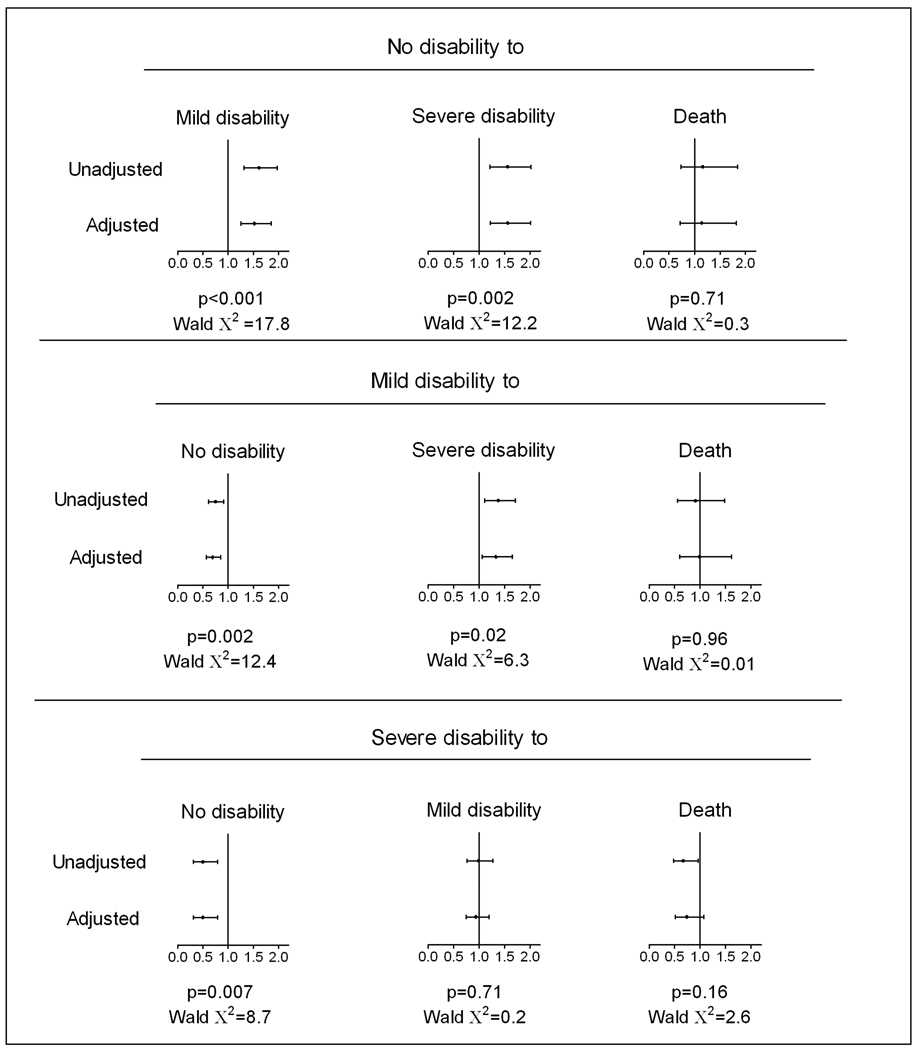

Figure 1 presents the unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for the associations between depression and the subsequent functional transitions. In the adjusted model, participants who were depressed were more likely than those who were non-depressed to transition from no disability to mild (HR=1.52; 95% CI 1.25, 1.85) and severe (HR=1.57; 95% CI 1.22, 2.01) disability, and from mild disability to severe disability (HR=1.33; 95% CI 1.06, 1.65); and were less likely to transition from mild disability to no disability (HR=0.69; 95% CI 0.57, 0.85) and from severe disability to no disability (HR=0.50; 95% CI 0.31, 0.79). Depression was not associated with the transitions from any of the three disability states to death. When the alternative cutpoint of 16 was used for the CES-D, the results did not change appreciably with only one exception; depression was no longer associated with the transition from mild to severe disability (HR=1.22; 95% CI 0.99, 1.51).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios of the association between depression and subsequent functional transitions. p-values (Wald chi-square = 144 with 19 degrees of freedom) refer to the results from the fully adjusted model that controlled for sex, race, education, and the following time-varying covariates; age, whether or not participants lived alone, number of chronic conditions, cognitive status, physical frailty, physical activity, and antidepressant medication use, and included adjustment for multiple comparisons based on a 5% False Discovery Rate.

CONCLUSIONS

In this longitudinal study of older persons, which included multiple assessments of depressive symptoms and monthly assessments of disability over the course of nearly 10 years, we evaluated the association of clinically significant depressive symptoms with transitions between states of disability and independence in an attempt to better elucidate the role of depressive symptoms in the disabling process. Our rigorous analysis, which used a competing risk framework, provides very strong evidence that clinically significant symptoms of depression are associated with transitions into and out of disability states in older persons. We found that participants considered to be depressed were more likely than those who were non-depressed to develop both mild and severe disability and to become more severely disabled in the setting of mild disability, and were less likely to recover independent function in the setting of both mild and severe disability. Yet, depression was not associated with mortality among those with either mild or severe disability.

Among community-living older persons, the association between depression and the onset of disability is well-established.(4, 5) Nonetheless, prior studies have not attempted to distinguish between different types of disability severity, despite evidence that the burden of disability varies widely among older persons.(5, 9) The results of the current study indicate that experiencing clinically significant depressive symptoms is a strong determinant of a broader array of disability outcomes, including transitions from mild to severe disability. We found, however, that depressive symptoms were associated with the transition from mild to severe disability only when the more stringent cutpoint of ≥20 was used for the CES-D. Our results highlight the importance of identifying high depressive symptoms to determine who may be likely to become more severely disabled over time. Because the use of formal and informal health care services increases with worsening disability,(29) identifying and treating depressive symptoms among older persons with mild disability could potentially reduce the financial and nonfinancial costs of care by preventing the progression of disability.

Depression is known to impede recovery after a catastrophic event, such as stroke.(30) However, relatively little is known about the association between depression and recovery from disability over time among older persons, despite evidence that recovery from disability is common.(21, 31) We found that participants with clinically significant depressive symptoms were less likely than those without depression to recover their independence in the setting of both mild and severe disability. This finding persisted after adjustment for factors such as physical frailty and antidepressant medication use that have previously been found to be associated with recovery from disability.(32, 33) These results suggest that the depressive features themselves, such as reduced energy, may impede recovery from disability.

Disability has been found to be strongly associated with mortality,(34) particularly among older persons with severe disability.(35) However, whether the association between disability and mortality is stronger among depressed older persons is uncertain. We found that the transition from either of the disabled states to death did not differ according to whether participants were depressed or non-depressed, thereby providing evidence that once older persons are disabled, whether or not they are depressed does not influence their likelihood of dying.

There are several potential limitations to this study that warrant comment. In the absence of a diagnostic measure, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, we were unable to determine the prevalence of major depression among the study participants. To address this limitation, we used a cutpoint of ≥20 on the CES-D, previously recommended to minimize the likelihood of misclassifying older persons as having high depressive symptoms.(20) We found that the rate of clinically significant depressive symptoms at baseline (13.3%) was much higher than the reported rate of major depression in comparable populations, thereby highlighting the distinction between “clinically significant depressive symptoms” and major depression. Because the CES-D includes somatic items (e.g., I could not get “going;” I did not feel like eating, my appetite was poor), it is possible that symptoms of physical illness such as fatigue or weight loss could have falsely inflated the CES-D score for some participants.(36) Similarly, participants with disability may have been more likely to endorse somatic items, thereby inflating their score.

The omission of eating, toileting and dressing from the monthly assessments of ADL disability may have led us to misclassify the severity of disability, and consequently the functional transitions. However, we found very high agreement when disability severity was classified using 4 ADLs versus 7 ADLs, thereby supporting our use of a smaller set of ADLs to assess severity of disability each month. Although our assessment of ADL disability was based on self-reported information rather than performance-based measures, these two strategies have comparable reliability in older persons (37, 38). The current analysis was restricted to ADL disability. In future work, we plan to evaluate the longitudinal relationship between depressive symptoms and transitions in mobility disability and disability in instrumental activities of daily living.

Although we adjusted for the use of antidepressant medications, information regarding the dose, dosing schedule, adherence, indication, and start of treatment was not available. Because Trazodone and Amitriptyline were not coded as antidepressant medications, participants who were prescribed these medications specifically for depression may have been misclassified as not taking an antidepressant medication. However, at any given time point during the study, between one third to one half of the participants taking either Trazodone or Amitriptyline reported taking another antidepressant, thereby reducing potential misclassification. Information was not available on prior history of either disability or depressive symptoms. Consequently, we could not determine if a participant’s first transition from a non-disabled to a disabled state represented incident disability. Nor could we establish the duration of depressive symptoms among participants who experienced clinically significant depressive symptoms at baseline. Although the MMSE is the most commonly used instrument for evaluating cognition in clinical practice, it does not assess executive function. Hence, it is possible that there remains residual confounding by cognitive status.(39) Lastly, because our study participants included members of a single health plan, the generalizability of our findings to other older adult populations may be questioned. As previously noted, however(10), the demographic characteristics of our study population, including years of education, closely mirror those of persons aged 70 years or older in New Haven county, which, in turn, are comparable to those in the United States as a whole, with the exception of race. New Haven county has a larger proportion of non-Hispanic whites in this age group than in the United States, 91% vs. 84%.(40) Furthermore, generalizability depends not only on the characteristics of the study population but also on its stability over time. Strengths of our study include a high participation rate, completeness of data collection and low rate of attrition for reasons other than death which all enhance the generalizability of our findings, and at least partially offset the absence of a population-based sample.

In conclusion, our findings highlight the importance of clinically significant depressive symptoms, which are potentially modifiable, on transitions into and out of disability among older persons. More broadly, our findings underscore the complexity of the relationship between depressive symptoms and disability. Future work is needed to evaluate the likely reciprocal relationship between depression and functional transitions in older persons and to determine if treatments, such as behavioral interventions, prevent or delay the onset and/or progression of both depression and disability in this population.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Brookdale Foundation and grants from the National Institute on Aging [K01AG031324 to LCB, R37AG17560 to TMG, and R01AG022993 to TMG]. The study was conducted at the Yale Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center [P30AG21342]. Dr. Gill is supported by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research from the National Institute on Aging [K24AG021507].

We thank Denise Shepard, BSN, MBA, Andrea Benjamin, BSN, Paula Clark, RN, Martha Oravetz, RN, Shirley Hannan, RN, Barbara Foster, Alice Van Wie, BSW, Patricia Fugal, BS, Amy Shelton, MPH, and Alice Kossack for assistance with data collection; Wanda Carr and Geraldine Hawthorne for assistance with data entry and management; Peter Charpentier, MPH for development of the participant tracking system; and Joanne McGloin, MDiv, MBA for leadership and advice as the Project Director.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No Disclosures to Report

This work was presented as an oral presentation at the 2009 American Geriatrics Society Meetings, Chicago, IL.

Author Contributions:

Dr. Barry had full access to the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. None of the authors has any conflicts of interest including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. The specific contributions are enumerated in the authorship, financial disclosure, and copyright transfer form.

Contributor Information

Lisa C. Barry, Email: lisa.barry@yale.edu.

Terrence E. Murphy, Email: terrence.murphy@yale.edu.

Thomas M. Gill, Email: thomas.gill@yale.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:249–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mueller TI, Kohn R, Leventhal N, et al. The course of depression in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Himelhoch S, Weller WE, Wu AW, et al. Chronic medical illness, depression, and use of acute medical services among Medicare beneficiaries. Medical Care. 2004;42:512–521. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000127998.89246.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cronin-Stubbs D, Mendes de Leon CF, Beckett LA, et al. Six-year effect of depressive symptoms on the course of physical disability in community-living older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3074–3080. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.20.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geerlings SW, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, et al. The longitudinal effect of depression on functional limitations and disability in older adults: an eight-wave prospective community-based study. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1361–1371. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manton KG, Gu X. Changes in the prevalence of chronic disability in the United States black and nonblack population above age 65 from 1982 to 1999. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6354–6359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111152298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill TM, Kurland B. The burden and patterns of disability in activities of daily living among community-living older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:70–75. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy SE, Dubin JA, Holford TR, et al. Transitions between states of disability and independence among older persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:575–584. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penninx BW, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, et al. Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: longitudinal evidence from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1346–1352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gill TM, Desai MM, Gahbauer EA, et al. Restricted activity among community-living older persons: incidence, precipitants, and health care utilization. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:313–321. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill TM, Williams CS, Tinetti ME. Assessing risk for the onset of functional dependence among older adults: the role of physical performance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:603–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, et al. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153–162. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayers AG, Baldwin DS, Mayers AG, et al. Antidepressants and their effect on sleep. Human Psychopharmacology. 2005;20:533–559. doi: 10.1002/hup.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain.[update of Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD005454; PMID: 16034979] Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005454. CD005454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–481. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1701–1701. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, et al. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychology & Aging. 1997;12:277–287. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, et al. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyness JM, Noel TK, Cox C, et al. Screening for depression in elderly primary care patients. A comparison of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Recovery from disability among community-dwelling older persons. Jama. 2004;291:1596–1602. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Simonsick E, et al. Progressive versus catastrophic disability: a longitudinal view of the disablement process. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51:M123–M130. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.3.m123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allison PD. Missing Data. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang M, Fitzmaurice GM. A simple imputation method for longitudinal studies with non-ignorable non-responses. Biometrical Journal. 2006;48:302–318. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200510188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Therneau T, Grambsch P. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allison P. Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: A Practical Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin D, Wei L. The robust inference for the proportional hazards model. Journal of the American Statistical Society. 1989;84:1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaPlante MP, Harrington C, Kang T. Estimating paid and unpaid hours of personal assistance services in activities of daily living provided to adults living at home. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:397–415. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hadidi N, Treat-Jacobson DJ, Lindquist R. Poststroke depression and functional outcome: A critical review of literature. Heart Lung. 2009;38:151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf DA, Mendes de Leon CF, Glass TA, et al. Trends in rates of onset of and recovery from disability at older ages: 1982–1994. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62:S3–S10. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.1.s3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gainotti G, Antonucci G, Marra C, et al. Relation between depression after stroke, antidepressant therapy, and functional recovery. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2001;71:258–261. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.2.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardy SE, Gill TM. Factors associated with recovery of independence among newly disabled older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:106–112. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nybo H, Petersen HC, Gaist D, et al. Predictors of mortality in 2,249 nonagenarians--the Danish 1905-Cohort Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1365–1373. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van den Brink CL, Tijhuis M, van den Bos GA, et al. The contribution of self-rated health and depressive symptoms to disability severity as a predictor of 10-year mortality in European elderly men. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:2029–2034. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foelker GA, Jr, Shewchuk RM. Somatic complaints and the CES-D. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:259–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Myers AM, Holliday PJ, Harvey KA, et al. Functional performance measures: are they superior to self-assessments? J Gerontol. 1993;48:M196–M206. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.5.m196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, et al. Assessing the building blocks of function: utilizing measures of functional limitation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25:112–121. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson JK, Lui LY, Yaffe K, et al. Executive function, more than global cognition, predicts functional decline and mortality in elderly women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1134–1141. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US Census Bureau. 2003 http://factfinder.census.gov.