Abstract

This investigation adds to the growing body of scholarship on the psychosocial costs of racism to Whites (PCRW), which refer to consequences of being in the dominant position in an unjust, hierarchical system of societal racism. Extending research that identified five distinct constellations of costs of racism (Spanierman, Poteat, Beer, & Armstrong, 2006), we used multinomial logistic regression in the current study to examine what factors related to membership in one of the five PCRW types during the course of an academic year. Among a sample of White university freshmen (n = 287), we found that (a) diversity attitudes (i.e., universal diverse orientation and unawareness of privilege) explain PCRW type at entrance; (b) PCRW type at entrance explained participation in interracial friendships at the end of the year; (c) 45% of participants changed PCRW type during the course of the year; and (d) among those who changed type, particular PCRW types at entrance resulted in greater likelihood of membership in particular PCRW types at the end of the year.

Keywords: costs of racism to Whites, White racial attitudes, White guilt, racial empathy

As historically White colleges and universities1 become increasingly racially diverse and campus initiatives are implemented to address racial insensitivity expressed by White students, it is important to understand the variety and complexity of White students’ racial attitudes and experiences. Research is needed that not only addresses expressions of White racism (i.e., expressions that are embedded in discriminatory institutional practices and widely socialized racist ideologies; Feagin & Vera, 1995) among White students, but also examines how White students react to and are affected by White racism on campus throughout their educational experiences. Recent scholarship on the psychosocial costs of racism to Whites provides a promising framework by which to understand White students’ reactions to White racism and how such reactions affect their campus diversity engagement. Thus, the current investigation builds on a recent study that identified five distinct categorizations of costs of racism to Whites (Spanierman, Poteat, Beer, & Armstrong, 2006) by examining potential factors (i.e., pre-college and college factors) that might be associated with particular constellations of costs of racism.

Defining Psychosocial Costs of Racism to Whites

Bowser and Hunt’s (1981) edited text entitled Impacts of Racism on White Americans presented a collection of scholarly writings that underscore the negative consequences of dominant group membership for White people, including inauthenticity (Terry, 1981), negative emotions (Karp, 1981) and maladjustment due to racism (Pettigrew, 1981). The specific phrase costs of racism to Whites was conceived by Kivel (1996) and is defined as negative psychosocial consequences that Whites experience as dominant group members in a system of societal racial oppression. Goodman (2001) further conceptualized a comprehensive framework for understanding the costs of oppression with particular attention to the ways in which structural oppression not only disproportionately benefits privileged group members, but also comes with a range of negative consequences. She outlined several domains of costs, such as moral and spiritual, psychological, social, and material. In search of a parsimonious theory that could be operationalized, Spanierman and Heppner (2004) synthesized Kivel and Goodman’s theoretical approaches and conceptualized a tripartite model of cognitive, affective, and behavioral costs of racism to Whites. Examples include distorted beliefs about race and racism, such as reliance on stereotypes (i.e., cognitive), guilt regarding unearned privilege and irrational fear of racial and ethnic minority persons (i.e., affective), and limited association with people of different races or self-censoring in interracial contexts (i.e., behavioral). These costs are in no way comparable to the substantial economic, political, and social costs that racial and ethnic minorities face as a result of White racism. Nevertheless, even as Whites benefit from White racism, it is noteworthy that racism affects everyone in negative ways (Kivel, 1996; Tatum, 1992). Further, as colleges and universities become increasingly racially diverse and campus administrators are managing White student backlash2, there is an urgent need for research that focuses on understanding the variety of responses and experiences of White students to inform the design of educational interventions to promote social justice attitudes and behaviors among students.

Measuring Psychosocial Costs of Racism to Whites

To move from the theoretical to the practical and empirical, Spanierman and Heppner (2004) developed the Psychosocial Costs of Racism to Whites (PCRW) scale, which is comprised of three distinct subscales that primarily assess affective costs of racism: (a) White Empathic Reactions toward Racism (e.g., sadness and anger about the existence of racism; also known as White empathy); (b) White Guilt (i.e., remorse about race-based advantage); and (c) White Fear of People of Other Races (i.e., irrational fear and mistrust of racial minorities, also known as White fear).

Several demographic factors and background characteristics, as well as a number of theoretically meaningful race-related constructs, have been associated with the PCRW scales. Across samples of undergraduates, graduate students, and employed adults, women score significantly higher than men on White empathy (Poteat & Spanierman, 2008; Spanierman & Heppner, 2004; Spanierman et al., 2006; Spanierman, Poteat, Wang, & Oh, 2008) and on White guilt among graduate psychology students (Spanierman et al., 2008). Higher levels of White empathy and guilt also have been associated with higher levels of multicultural education, racial awareness and cultural sensitivity among students (Spanierman & Heppner; Spanierman et al., 2008), and greater openness to diversity among employed adults (Poteat & Spanierman, 2008). In contrast, White fear has been related to lower levels of multicultural education, racial awareness, and cultural sensitivity, less exposure to racial minorities, and fewer interracial friendships (Spanierman & Heppner); lower openness to diversity (Poteat & Spanierman, 2008); less support for affirmative action and higher levels of racial prejudice (Case, 2007). Because the White fear scale operates differently from the White empathy and guilt scales and a total score cannot be computed, the authors of the PCRW recommended either examining subscales separately or using multivariate analysis to combine the three scales.

Patterns of Costs of Racism to Whites

Racial attitudes are complex and nuanced. Thus, addressing the complexities of White individuals’ experiences of the psychosocial costs of racism is better served through analyses that consider more than just single scale scores. To consider the three PCRW subscales simultaneously, Spanierman and colleagues (2006) used cluster analysis to examine patterns of costs of racism to Whites. Results revealed five distinct cluster groups, or PCRW types, among 230 White undergraduate students. These findings represented a more integrative and nuanced portrayal of White individuals’ experiences of the costs of racism, thus providing richer information than single scale scores. For example, the high guilt / high empathy combination (Antiracist) is qualitatively different than the high guilt / high fear combination (Fearful Guilt), indicating that White guilt by itself is less informative than viewing guilt in combination with other costs. Based on Spanierman et al.’s (2006) findings, the five types are:

Informed Empathy and Guilt (Antiracist)

Among the five types, Antiracist reflects the highest levels of White empathy and guilt, coupled with the lowest irrational fear of racial minorities. Further, this type contained the fewest participants of all the types, a higher proportion of women in the sample (19%) than men (6%), and a greater proportion of self-identified Democrats (21%) than Republicans (10%). Individuals reflecting the Antiracist type reported the highest level of multicultural education, greatest racial diversity among friends, most support for affirmative action, and greatest cultural sensitivity among all of the types. Accordingly, individuals in this type exemplified lower levels of color-blind racial attitudes than all other types.

Empathic but Unaccountable

The most prevalent of the five types in previous research, this type is characterized by high White empathy with low levels of White guilt and fear. This type differs from Antiracist because high White empathy exists without the accompanying White guilt. Similar to Antiracist, these individuals reported racial diversity in their friendship group and awareness of blatant racial issues. However, Empathic but Unaccountable lacked critical awareness of racial privilege, as measured by the Color-blind Racial Attitudes Scale (Neville, Lilly, Duran, Lee, & Browne, 2000). A high proportion of men (28%) and Democrats (26%) were concentrated in this type in previous research.

Fearful Guilt

High levels of White guilt and fear, with moderate empathy, exemplify this PCRW type. Because this type has been linked to awareness of racial privilege, the highest proportion of Democrats (30%), and moderate to extensive levels of multicultural education, it appears similar to the Antiracist type (Spanierman et al., 2006). Key differences between this type and Antiracist are that Fearful Guilt exhibits lower levels of racial empathy and higher levels of racial fear. Accordingly, persons in this type report few interracial friendships.

Unempathic and Unaware (Oblivious)

This type is characterized by low levels of White empathy and guilt, along with moderate White fear. Similar to Helms’ (1990) White racial identity status of Contact, this attitude type displays racial-colorblind ideology (see Bonilla-Silva, 2006; Neville et al., 2000), in which one is oblivious to issues of race and racism. Similar to the Insensitive and Afraid type described below, individuals in this type reported low levels of racial privilege awareness, little to no multicultural education, as well as having few close friends of other races. The highest proportion of men (29%) was concentrated in this type.

Insensitive and Afraid

Among the types, this one displays the lowest levels of White empathy and guilt, coupled with the highest White fear scores. Moreover, persons in this type reported the lowest levels of multicultural education, cultural sensitivity, racial awareness, support for affirmative action, and exposure to people of color; they also represented the highest proportion of self-identified Republicans (32%) and lowest proportion of Democrats (10%).

PCRW Types and Campus Diversity Engagement

In light of recent diversity initiatives that aim to increase White students’ awareness of racial issues and foster inclusivity, research is needed to understand the ways in which White students’ racial affect might be associated with their participation in campus diversity activities. A number of conceptual and practical links exist between students’ PCRW types and their engagement in campus diversity activities. First, theory on costs of racism types suggests that Antiracist and Empathic but Unaccountable types might be more willing to engage in campus diversity activities due to their high level of racial empathy and low level of fear of people of color (see Spanierman et al., 2006). Second, understanding the subtle distinctions between Antiracist, Empathic but Unaccountable, and Fearful Guilt types with regard to pre-college as well as college diversity experiences could be useful for educators and student affairs professionals in developing interventions to foster social justice attitudes among White students. It would be useful, for example, if educators were aware of key factors that differentiated those students who took an active stance to dismantle racism as opposed to those who simply felt bad about its existence. Finally, because racial issues often elicit strong emotional reactions (Lucal, 1996), faculty and administrators could benefit from understanding how White students’ PCRW type might change as a result of their engagement in campus diversity activities. Ultimately, research might identify the conditions in which students are more likely to reflect Antiracist attitudes as opposed to others. Thus, empirical research is needed that extends previous investigation of the PCRW types to understand whether these types explain students’ participation in diversity activities and whether such activities are linked to PCRW type change during the course of an academic year.

The Current Investigation

In the current investigation, we are concerned with examining whether particular factors (i.e., pre-college characteristics, diversity attitudes at entrance, and participation in diversity activities during the course of an academic year) might help to explain the PCRW types. With regard to pre-college factors, we examine: gender, high school and neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood wealth and poverty levels, and high school interracial friendships to obtain a contextual understanding of our participants. Because empirical investigation has indicated gender differences in PCRW types and other racial attitude variables (e.g., Astin, 1997), we examine this variable in the current study. Further, previous research supports the notion that self-reported exposure to people of color is associated with costs of racism to Whites. To build on this self-reported data, we use census and high school data in the current study to gain a more contextual understanding of participants. We examine neighborhood wealth and poverty levels based on previous literature that suggests that social class is associated with racial attitudes (e.g., out-group hostility toward those with low status; Oliver & Mendelberg, 2000). In addition to pre-college factors, we also assess particular diversity attitudes at entrance: universal diverse orientation and unawarenesss of racial privilege. Universal diverse orientation, which refers to openness to and appreciation of cultural diversity, is a critical component of the types of attitudes administrators wish to instill in all students, but by itself is insufficient. As scholars (e.g., Castillo et al., 2006; Lawrence & Bunche, 1996; Lucal, 1996; Tatum, 1992) suggest, White students also must increase their self-awareness as racial beings and examine their own White privilege to realize campus diversity efforts.

We also were interested in whether students participated in diversity activities throughout the year, and further how their participation in such diversity experiences might explain their PCRW type. In his review of the literature on intergroup relations in higher education, Engberg (2004) refers to diversity engagement as comprised of student participation in formal and informal campus diversity activities. Most often, formal diversity experiences are defined as university sponsored activities (e.g., diversity courses, workshops, and other programming), whereas informal diversity experiences are comprised of interracial friendships and other informal interactions. For the purposes of the current study, we defined diversity engagement as student participation in formal and informal campus diversity activities.

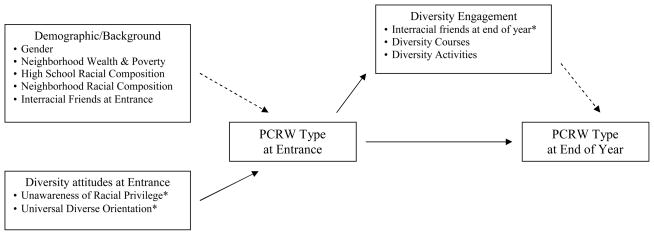

Because PCRW types have the potential to inform our understanding of White university students’ diversity engagement, underscoring the complexity and heterogeneity of White individuals’ racial affect in response to the changing face and landscape of the university, the purpose of our study is fourfold. First, we explore potential predictors of these types at entrance (i.e., background characteristics and initial diversity attitudes). Second, we examine whether PCRW types explain students’ diversity engagement in college (i.e., participation in diversity courses, activities, and interracial friendships). Third, we investigate whether PCRW type changes during the course of the first year of college and, if so, what is the nature of that change. Fourth, taking all the variables into account collectively (i.e., background characteristics, diversity attitudes, and diversity engagement throughout the year) and controlling for PCRW type at entrance, we test whether any of these variables predicts PCRW type at the end of the year. See Figure 1 for an overall schematic of our investigation.

Figure 1.

Overall Schematic of Analyses Conducted

Note. Significant effects are denoted by solid lines; non-significant effects are denoted by dashed lines. The arrows point from predictor variables to outcome/response variables. * refers to specific variables that were significant; PCRW Type at entrance predicted interracial friends at end of year, but interracial friends did not predict PCRW type at end of year.

Method

Participants

At a large predominantly White Midwestern university, 287 self-identified White freshman college students completed an online survey at entrance (Time 1) and at the end of the first year (Time 2). Among these participants, 54.7 % were women and 41.8% were men; 10 participants (3.5 %) did not report their gender. The mean age of participants at entrance was 18.19 years (SD = 0.40, range = 18–20); 12 participants did not complete the item. The majority of participants attended a public high school (67.9%), whereas 6.6% attended a private school with 25.4% not reporting on this item. The majority of students’ (71.1 %) permanent residences were in-state. Approximately half (50.2%) of the participants had not taken a multicultural course in high school, whereas 37.6% had taken one or two courses; 8.7% had taken 3 or more courses, and 3.5% did not complete the item about such courses.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire

A demographic questionnaire was administered at entrance (Time 1) to obtain information such as: age, gender, type of high school (public or private) and high school multicultural courses.

Social and economic context

Participants’ social and economic backgrounds were determined through two sources: high school racial and economic information and neighborhood-level racial and economic information. During Time 1 data collection, we asked participants’ to include the name of their high school. We then used two websites to determine racial composition of in-state public high schools (Illinois State Board of Education E-Report Card Public Site, 2008) and private and out-of-state high schools (Great Schools, 2008).

Also during Time 1 data collection, we asked participants to provide the street address of their residence while in high school. Research assistants retrieved data from the 2000 U.S. Census and public school databases, including racial composition and poverty and income levels of the participants’ neighborhoods. We first used the Census 2000 track and block numbers followed by the Census 2000 Summary File 3 data file (STF 3) to retrieve specific information regarding race (% of each racial/ethnic group in that area), income (% of household/family income in 1999 over $50,000), and poverty status (% of household/family income in 1999 below the poverty level). We refer to these variables as (a) high school racial composition, (b) neighborhood racial composition, (c) family income wealth, and (d) family income poverty.

Unawareness of racial privilege

We used the Unawareness of Racial Privilege subscale of the Color-blind Racial Attitudes Scale-Short Form (CoBRAS-SF; Neville, Low, Liao, Walters, & Landrum-Brown, 2007) to assess students’ lack of awareness of White privilege in U.S. society at entrance (Time 1). The 14-item CoBRAS-SF is an abbreviated version of the original 20-item CoBRAS (Neville et al., 2000) and psychometric properties are similar across the two measures. Sample items from the 6-item Unawareness of Racial Privilege subscale include: “Everyone who works hard, no matter what race they are has an equal chance to become rich” and “White people have certain advantages because of the color of their skin (reverse scored).” The items are rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) with higher scores representing higher levels of a particular aspect of racial color-blindness (i.e., unawareness of privilege). Unawareness of Racial Privilege has been found to be associated with a range of social beliefs and actions, including greater racial and gender insensitivity among a predominantly White sample (Neville et al., 2000). The internal consistency of the longer version has been well documented among White students (i.e., α = .84 –.91; Neville et al., 2000), and reliability estimates for the short version have been found to be similar (Neville et al., 2007). For the present investigation, the internal consistency estimate of the Unawareness of Racial Privilege subscale was α =. 84.

Universal diverse orientation (UDO)

At entrance (Time 1), we used the Miville-Guzman Universality-Diversity Scale-Short (Fuertes, Miville, Mohr, Sedlacek & Gretchen, 2000) to assess students’ openness to and appreciation of cultural diversity. The UDO construct includes racial diversity but also encompasses a broader range of social group identities, such as persons with disabilities and those from other countries. The short form is comprised of 15 items from the original 45-item scale (Miville-Guzman Universality-Diversity Scale; Miville et al., 1999) and uses a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The full scale correlation between the original and the shortened versions has been shown to be r = .77 (p < .001). Items reflect (a) Diversity of Contact (5 items; e.g., “I attend events where I might get to know people from different racial backgrounds”), (b) Relativistic Appreciation of Oneself and Others (5 items; e.g., “Knowing about the different experiences of other people helps me understand my own problems better”), and (c) Comfort with Differences (5 items; e.g., “I am only at ease with people of my own race” reverse scored). Higher scores represent greater openness to and appreciation of cultural diversity. The construct validity of the original scale has been established with a number of related scales, such that higher UDO scores were associated with positive racial identity (for Whites), empathy, and feminist attitudes, while negatively associated with dogmatism and homophobia (Miville et al., 1999). The internal consistency of the short version of the scale has ranged from α = .73 (Thompson, Brossart, Carlozzi, & Miville, 2002) to α = .83 (Singley & Sedlacek, 2004). Due to the modest intercorrelations of the subscales (range = .27–.45), our desire to understand the broad impact of openness to and appreciation of cultural diversity, and the parsimony of using a general measure, we used the total scale score which evidenced acceptable internal consistency in the present investigation (α = .85.)

Diversity courses

During Time 2, participants were asked to indicate the number of diversity-related courses taken during their first year of college on a 3-point scale (0 = none, 1 = one or two, 2 = three or more). We prompted participants with four types of diversity courses (i.e., ethnic studies, gender and women’s studies, general diversity courses, and intergroup relations dialogue courses) and “other,” so that students could specify a course. The average number of courses was 0.12 (SD = 0.22, range = 0–2), indicating that most students (62.4%) took no diversity courses, whereas 32.8% took at least one course; 4.8% did not respond to this item.

Diversity activities

Participants also were asked to indicate whether they were aware of and had participated in 11 types of campus diversity activities, programs, or events (e.g., Asian Awareness Week activities and Martin Luther King events) on a 3-point scale (0 = not aware of this or have not participated in this; 1 = participated in this a little [once or twice]; 2 = participated in this quite a bit [three or more times]). The average number of activities was 0.13 (SD = 0.24, range = 0–2). Further, half of the sample (49.5%) indicated that they participated in no diversity activities, whereas 42.5% participated in at least one activity; 8% did not respond.

Interracial friendships

During entrance (Time 1) and the end of the first year (Time 2), participants were asked to respond to five items that indicated the racial backgrounds of people who are among their inner circle of friends (i.e. close friends). We used a 5-point Likert-type response format, ranging from 1 (none or almost none) to 5 (all or almost all), to assess the proportion of participants’ friends who were: White, African American, Latino/a, Asian American, and Native American. To determine interracial friendships, we averaged scores on the items that represented racial minority friends for Time 1 (M = 1.90, SD = 0.53, range = 1–5) and Time 2 (M = 2.03, SD = 0.51, range = 1–5).

Psychosocial Costs of Racism to Whites Scale (PCRW; Spanierman & Heppner, 2004)

During Time 2, we used the PCRW to assess participants’ affective costs of societal racism. The 16-item self-report measure uses a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Higher scores reflect higher experiences of costs. The measure includes three subscales: (a) White Empathic Reactions toward Racism (6 items, “I am angry that racism exists”), (b) White Guilt (5 items, “Sometimes I feel guilty about being White”), and (c) White Fear of People of other Races (5 items, “I am distrustful of people of other races”). Among White university students, internal consistency estimates for each of the subscales have ranged as follows: White empathy α = .70 to .85, White Guilt α = .73 to .81, and White fear α = .63 to .78 (Case, 2007; Spanierman & Heppner, 2004; Spanierman et al., 2006). Temporal stability estimates over a 2-week period have ranged from .69 for White Guilt to .95 for White fear (Spanierman & Heppner, 2004). In the current investigation, coefficient alphas for the three PCRW subscales were .81 (White empathy), .82 (White Guilt), and .72 (White fear).

Procedures

Time 1

Data were collected in two waves -- beginning of fall (Time 1; at entrance) and near the end of spring (Time 2; end of year) -- for a larger campus project that examined general diversity attitudes across several racial groups. We sent individualized email invitations to a random sample of 1200 White freshman (excluding students under 18 years of age), requesting their participation in the web-based survey. As an incentive to complete the survey, we offered the opportunity to win one of seven cash prizes (one $500, two $100, and four $50). We sent two e-mail reminders, in one-week intervals, to encourage participation and enhance the response rate. The survey consisted of the following measures: a demographic questionnaire, items regarding high school diversity education and interracial friendships, the Unawareness of Racial Privilege subscale of the CoBRAS, the MGUDS-S to measure universal diverse orientation, and the PCRW. A number of additional measures were included for the larger study but were not analyzed in the current investigation. The response rate among the current Time 1 sample was approximately 50%.

Time 2

During the second data administration at the end of spring semester, we followed the same procedures as described above and sent an invitation to participate in a web-based survey to the 1200 White students. The measures were similar to those described above, except that items about college diversity courses, activities, and friendships replaced the high school diversity items. At the end of the first year, 533 participants completed the on-line survey (approximately 44% response rate); and, of these 533 participants, 315 completed the survey at entrance (Time 1) and the end of the year (Time 2). A unique code number for each participant was included in the recruitment emails during both data administrations. Participants entered their unique code to log on to the web survey, which enabled us to match participants’ data. Approximately 59% of those who completed Time 1 also completed Time 2. Because 28 participants did not complete a substantial portion of the PCRW in either data administration, these participants were not included in the analysis. In cases where the participant was missing only one or two PCRW items (n = 16), we used mean data imputation to calculate their scale scores. A total of 287 participants comprised the final sample used in this investigation.

Results

In this section, we describe descriptive statistics and correlations, and then present our analysis to test whether the PCRW types in the current study replicate previous findings (e.g., Spanierman et al., 2006). Next, we report the results of our fourfold analytic strategy, which are described below in greater detail.

Preliminary Statistics

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 1. Upon examining gender differences, we found that females scored higher (M = 4.61, SD = 0.66) than males (M = 4.24, SD = 0.68) on UDO, t(251.25) = −.3.18, p <.01. We also found significant gender differences for neighborhood racial composition with females coming from neighborhoods with a higher percentage of White individuals (M = .89, SD = 0.11) than males (M = .84, SD = 0.18), t(108.30) = −2.00, p = .05. Females also reported higher levels of White empathy (M = 4.68, SD = 0.84) than males (M = 4.29, SD = 0.88), t(249.67) = −3.66, p < .001. There were no significant gender differences on any other study variables.3

Table 1.

Intercorrelations, Means, and Standard Deviations for Study Variables

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family income: Wealth | — | −.63** | −.12 | .18* | .06 | .01 | −.00 | .11 | −.04 | .06 | .05 | −.06 | 73.6% | 16.2% |

| 2. Family Income: Poverty | — | .03 | −.23** | −.02 | .08 | .15* | −.12 | .08 | −.16* | −.02 | .03 | 2.5% | 3.3% | |

| 3. High School Racial Composition | — | .42** | −.24** | .10 | .06 | .16* | .01 | −.07 | −.08 | .02 | 78.9% | 19.5% | ||

| 4. Neighborhood Racial Composition | — | −.17* | −.02 | .01 | .18* | −.02 | .07 | .11 | .05 | 87.2% | 14.1% | |||

| 5. Interracial Friendship Time1 | — | .07 | −.02 | −.22** | .23** | .01 | .07 | .12 | 1.90 | 0.53 | ||||

| 6. PCRW Empathy Time 1 | — | .29** | −.31** | .47** | −.26** | .15* | .17** | 4.67 | 0.78 | |||||

| 7. PCRW Guilt Time 1 | — | −.02 | .16** | −.40** | .14* | .21** | 2.09 | 0.98 | ||||||

| 8. PCRW Fear Time 1 | — | −.50** | −.04 | .02 | −.06 | 2.60 | 0.88 | |||||||

| 9. UDO | — | −.10** | .18** | .26** | 4.49 | 0.68 | ||||||||

| 10. Unawareness of Privilege | — | −.13* | −.15* | 3.79 | 0.87 | |||||||||

| 11. Diversity Courses | — | .51** | 0.12 | 0.22 | ||||||||||

| 12. Diversity Activities | — | 0.13 | 0.24 | |||||||||||

| 13. Interracial Friends T2 | −.06 | .01 | −.11 | −.11 | .40** | .11 | −.01 | −.32** | .33** | −.02 | .11 | .26** | 2.03 | 0.51 |

| 14. PCRW Empathy T2 | −.06 | .04 | .11 | −.06 | .11 | .67** | .37** | −.33** | .47** | −.28** | .14* | .22** | 4.51 | 0.87 |

| 15. PCRW Guilt Time 2 | −.00 | .12 | .05 | .04 | −02 | .28** | .64** | −.06 | .18* | −.31** | .22** | .20** | 2.12 | 1.03 |

| 16. PCRW Fear Time 2 | .11 | −.13 | .17* | .13 | −.26** | −.26** | −.08 | .70** | −.51** | .07 | −.05 | −.16* | 2.64 | 0.90 |

| Measure | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13. Interracial Friends Time 2 | — | .20** | .04 | −.39** |

| 14. PCRW Empathic Reactions Time 2 | — | .32** | −.40** | |

| 15. PCRW Guilt Time 2 | — | .01 | ||

| 16. PCRW Fear Time 2 | — |

Note: Family Income: Wealth = the percent of families in the neighborhood that earned 50K or greater; Family Income: Poverty = the percent of families in the neighborhood that were considered at poverty or below; High School Racial Composition = the percent of high school that is White; Neighborhood Racial Composition = percent of neighborhood that is White; Interracial Friendship = average of interracial friends on scale 1 (none or almost none) through 5 (all or almost all); UDO = Miville-Guzman Universal Diverse Orientation Scale Short Form; Unawareness of Privilege = Unawareness of Racial Privilege subscale of the Color-blind Racial Attitudes Scale-Short Form; Diversity Courses = average number of courses across different categories of diversity courses; Diversity Activities = number of diversity activities across 11 different categories of activities.

p < .05,

p < .01.

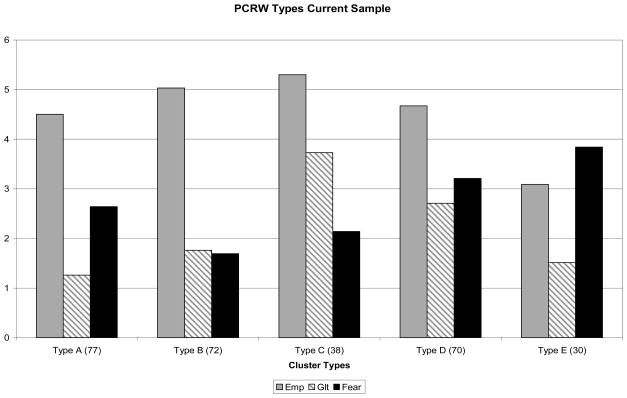

Replicating Cluster Groups

We conducted a nonhierarchical k-means cluster analysis for the current sample using MATLAB, which allowed for the use of 100 multiple random starts to avoid the problem of local optima (Steinley, 2003). To assess how well the five-cluster solution replicated previous work, we compared the current sample to a sample from an independent data set (i.e., the primary data set used in Spanierman et al., 2006). The validation sample consisted of 230 White undergraduate students from a large Midwestern university; cluster groups ranged in size from 34 to 66 participants. Overall, the five cluster groups from the current and validation samples exhibited similar mean patterns of White empathy, guilt, and fear. For the present sample, the number of participants in each cluster group was: Cluster A (Unempathic and Unaware [Oblivious]; n = 77), Cluster B (Empathic but Unaccountable; n = 72), Cluster C (Informed Empathy and Guilt [Antiracist]; n = 38), Cluster D (Fearful Guilt; n = 70), Cluster E (Insensitive and Afraid; n = 30). See Figure 2 for the mean score patterns of the PCRW types.

Figure 2.

Psychosocial Cost of Racism Types: Current Sample (Time 1)

Note: Type A = Oblivious, Type B = Empathic but Unaccountable, Type C = Antiracist, Type D = Fearful Guilt, and Type E = Insensitive and Afraid. Numbers in parentheses refer to number of participants in each PCRW type.

We noted some similarities and some distinctions between the current and validation samples. First, the proportions of individuals (i.e., proportion of each sample) represented in each type did not differ significantly across samples (Pearson’s chi-square statistic , p =.06); however, the marginally significant p-value reflects the possibility that there might be differences in proportions of individuals in particular types across samples. Second, we found that the distribution of gender within the current cluster groups also was similar to those in the validation sample ( , p = .35). Third, as recommended by Henry, Tolan, and Gorman-Smith (2005), we conducted a 2 (sample) x 5 (cluster group) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to test if the means for the three subscales were similar in each cluster group across samples. If the cluster groups in the current sample replicate the validation sample, then no interaction effect would be present. There was no main effect for sample, Λ = .99, F(3, 505) = 2.09, p = .01, η2 = .01. There was a main effect for cluster, Λ = .07, F(12, 1336) = 200.83, p < .01, η2 = .60, and a significant interaction, Λ = .80, F(12, 1336) = 9.97, p < .01, η2 = .07. Thus, current sample did not exactly replicate the PCRW types found in the 2006 sample, and we noted slight variations in a number of the types. Specifically, using follow up multiple comparison procedures to control for Type I error (α = .003), we found significantly lower levels of White empathy in the current sample than the validation for the Insensitive and Afraid type; however, this difference offers stronger support for the original conceptualization of this type (i.e., lacking empathy). We identified another difference for the Oblivious type such that the current sample scored significantly higher on empathy and fear than did the validation sample. Additionally, we found significantly lower levels of White fear and White empathy for the Empathic but Unaccountable type. With regard to Empathic but Unaccountable, the difference for fear is in the direction that is conceptually consistent with this type whereas the finding for empathy is not. Finally, the current sample displayed significantly lower levels of guilt in the Fearful Guilt type.

Although the means in each type were not identical across samples, the overall patterns of means within each PCRW type cluster were indeed similar across samples. For example, Insensitive and Afraid reflected low White empathy and guilt, along with high White fear, across samples. Finally, we ran the same set of analyses to assess if Time 2 PCRW type also replicated the validation sample type and found that the Time 2 type preserved the overall structure of the types. These follow-up analyses are available upon request from the authors.

Analysis Strategy

Four sets of analyses were conducted to address our research questions. First, we used multinomial logistic regression to determine how demographic/background characteristics (i.e., gender, neighborhood wealth and poverty, racial composition of neighborhood and high school, and interracial friendships at entrance) and diversity attitudes at entrance (i.e., universal diverse orientation and unawareness of privilege) predicted PCRW type at entrance. Second, we fit log-linear models to the cross-classification of students’ PCRW types at entrance by their types at the end of the year to study whether and how students changed PCRW type during the course of the academic year. Third, we conducted another multinomial logistic regression to examine how PCRW type at entrance differed with respect to diversity engagement during the first year in college (i.e., diversity courses, diversity-related activities, and interracial friendships at the end of the year). Fourth, we used multinomial logistic regression to examine how diversity engagement during the academic year predicted PCRW type at the end of the year. Taken together these analyses explain what factors are related to PCRW type at college entrance, the nature of type change across the first year, how initial PCRW type predicts engagement with diversity during the first year, and what predicts PCRW type at the end of the year.

Predicting Initial PCRW Type at Beginning of College

To answer our first question as to what factors predict PCRW type at entrance, we used multinomial logistic regression, which extends logistic regression for dichotomous to multi-category variables and allows for the prediction of category membership (Anderson & Rutkowski, 2007). Multinomial logistic regression also can be used to describe differences between categories on the basis of explanatory or predictor variables. We entered blocks of variables based on theory as well as temporal sequence; that is, we entered the block of pre-college variables (i.e., demographic/ background characteristics) first, followed by the variables measured at college entrance (i.e., diversity attitudes). At each step, we used Wald tests to examine explanatory variables, also referred to as individual predictors, and dropped those that were not able to significantly explain PCRW type. Odds ratios then were computed for each significant explanatory variable to interpret their effects on PCRW type membership. Since there are five PCRW types, odds ratios were computed for each possible pair of types.

Background variables

The demographic/background variables were: gender, family income wealth and poverty indices, high school and neighborhood racial composition, and interracial friendships upon entering college. These variables were non-significant both collectively (Wald test, , p = .07) and individually (see Table 2). These variables were not included in further models given their relative inability to explain membership in the PCRW types.

Table 2.

Wald Tests to Indicate Relations of Study Variables to PCRW Type at Entrance

| Variable | χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicting PCRW Type at Entrance | |||

| Background Variables | 35.11 | 24 | .070 |

| Gender | 4.40 | 4 | .354 |

| Family Income: Wealth | 7.93 | 4 | .094 |

| Family Income: Poverty | 4.32 | 4 | .364 |

| High School Racial Comp | 3.29 | 4 | .511 |

| Neighborhood Racial Comp | 4.69 | 4 | .321 |

| Interracial Friends Time 1 | 6.14 | 4 | .189 |

| Diversity Attitude at College Entrance | 80.43* | 8 | <.010 |

| Universal Diverse Orientation | 58.01** | 4 | < .001 |

| Unawareness of Privilege | 27.55** | 4 | < .001 |

| PCRW Type at Entrance Predicting College Diversity Engagement | |||

| Diversity Engagement | 27.42* | 12 | <.010 |

| Diversity Courses | 5.05 | 4 | .282 |

| Diversity Activities | 6.29 | 4 | .180 |

| Interracial Friends Time 2 | 18.47* | 4 | .001 |

Note. Family Income Wealth = the percent of families in the neighborhood that made 50K or greater; Family Income Poverty = the percent of families in the neighborhood that were considered at poverty or below; High School Racial Comp = the percent of high school that is White; Neighborhood Racial Comp = percent of neighborhood that is White; Interracial Friends = average of interracial friends on scale 1 (none or almost none) through 5 (all or almost all); UDO = Miville-Guzman Universal Diverse Orientation Scale Short Form; Unawareness of Privilege = Unawareness of Racial Privilege subscale of the Color-blind Racial Attitudes Scale-Short Form; Diversity Courses = average number of courses across different categories of diversity courses; Diversity Activities = number of diversity activities across 11 different categories of activities .

p < .05,

p < .001

Diversity attitudes

The second set of predictors reflecting diversity attitudes at entrance (i.e., UDO and Unawareness of Racial Privilege), were entered simultaneously into a model. Both UDO ( , p <.01) and Unawareness of Racial Privilege ( , p <.01) were significant independent predictors of PCRW type at entrance (see Table 2).

Odds Ratios for UDO and Unawareness of Racial Privilege

To interpret the effects of the significant predictor variables (UDO and Unawareness of Racial Privilege) on PCRW type at entrance, we computed odds ratios using the estimated parameters from the model. Only the significant odds ratios are reported in Table 3 along with their 95% confidence intervals. In general terms, higher UDO scores were associated with greater odds of membership in the Empathic but Unaccountable type than the Oblivious, Fearful Guilt, or Insensitive and Afraid types; greater odds of membership in the Antiracist type than the Oblivious, Fearful Guilt, or Insensitive and Afraid types; greater odds of membership in the Oblivious than Insensitive and Afraid types; and greater odds of membership in the Fearful Guilt than Insensitive and Afraid types. Furthermore, higher Unawareness of Racial Privilege scores related to greater odds of membership in Oblivious than the Antiracist and Fearful Guilt types; greater odds of membership in Empathic but Unaccountable than Antiracist and Fearful Guilt types; and greater odds of membership in Insensitive and Afraid than the Empathic but Unaccountable, Antiracist, and Fearful Guilt types. These results indicate that UDO and Unawareness of Racial Privilege were important in understanding the odds of membership in one type versus other types. Participants with higher UDO scores had greater odds of membership in cluster types with high White empathy, whereas those with higher Unawareness of Racial Privilege scores in most cases had greater odds of membership in cluster types with low White guilt.

Table 3.

Multinomial Logistic Regression 1 (Diversity Attitudes Predicting PCRW Types at Entrance) and Multinomial Logistic Regression 2 (PCRW Types at Entrance Predicting Interracial Friends Time 2)

| Unaware of Privilege Odds Ratio (95% CI) | UDO Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Interracial friends Time 2 Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCRW Types | ||||

|

|

3.52, (1.92, 6.46) | 2.47, (1.18, 5.18) | ||

|

|

1.58, (1.01, 2.46) | 3.91, (2.11, 7.27) | 4.59, (2.08, 10.10) | |

|

|

26.22, (10.02, 68.61) | 5.92, (2.15, 16.13) | ||

|

|

36.45, (12.46, 106.61) | 3.13, (1.05, 9.36) | ||

|

|

5.44, (2.54, 11.64) | |||

|

|

4.89, (2.27, 10.55) | |||

|

|

6.70, (2.76, 16.28) | |||

|

|

7.44, (3.12, 17.75) | |||

|

|

2.27, (1.46, 3.52) | |||

|

|

3.03, (1.76, 5.22) | |||

|

|

1.92, (1.01, 3.64) | |||

|

|

4.05, (1.96, 8.40) | |||

|

|

3.03, (1.61, 5.72) | |||

|

|

2.11, (1.27, 3.51) | |||

Note. UDO = Miville-Guzman Universal Diverse Orientation Scale Short Form; Unaware of Privilege = Unawareness of Racial Privilege Subscale of Color-blind Racial Attitudes Scale-Short; T2 = Time 2; Odds > 1 are significant (p < .05) and indicate greater likelihood of being in the first type listed (e.g., unit increase in UDO relates to 4.89 times more likely to be in Antiracist than Oblivious. Any odds ratios not presented are non-significant.

Assessing Change in PCRW Type from Beginning to End of First Year of College

Do students change PCRW type?

We used log-linear models to assess whether students’ PCRW type changed during the course of the academic year. Table 4 displays the cross-classification of students by Time 1 PCRW type (rows) and Time 2 PCRW type (columns). Individuals along the diagonal (55%) represent students who stayed in the same type during the first year of college; whereas, those in the off-diagonal (45%) changed to a different PCRW type. A log-linear model of independence4 failed to give a good representation of the data (Pearson’s chi-square statistic, , p < .01), which indicates that Time 1 and Time 2 types were related. The significant effect might have been driven by the large proportion of students who did not change type; therefore, we fit a log-linear model of quasi-independence that removed the effect of the diagonal (i.e., those who did not change, hereafter referred to as “stayers”) (Agresti, 2007). This model also failed to represent the data ( , p < .01), thus suggesting that there was some dependence between the beginning and ending PCRW types even while disregarding the “stayers.”

Table 4.

Cross Tabulation of PCRW Type at Entrance (Rows) and End of Year (Columns)

| Time 2 Type |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | Oblivious | Empathic but Unaccountable | Antiracist | Fearful Guilt | Insensitive and Afraid | Total |

| Oblivious | 42 (42.00) | 16 (16.12) | 1 (1.18) | 5 (4.77) | 13 (12.94) | 77 |

| Empathic but Unaccountable | 12 (10.25) | 42 (42.00) | 11 (11.37) | 7 (9.01) | 0 (0.37) | 72 |

| Antiracist | 0 (1.12) | 6 (3.00) | 24 (24.00) | 8 (9.12) | 0 (0.75) | 38 |

| Fearful Guilt | 16 (15.94) | 11 (13.20) | 12 (10.93) | 29 (29.00) | 2 (0.93) | 70 |

| Insensitive and Afraid | 8 (8.69) | 0 (0.69) | 0 (0.52) | 4 (2.10) | 18 (18.00) | 30 |

| Total | 78 | 75 | 48 | 53 | 33 | 287 |

Note. Numbers in parentheses are fitted values from the log-linear model of association.

To understand how PCRW type at entrance is related to PCRW type at the end of the year, we examined the adjusted or “Haberman” standardized residuals from the log-linear model of quasi-independence (Table 5). If quasi-independence holds, then these residuals should follow a standard normal distribution. Note that in each row, the largest negative residual(s) is approximately equal to the largest positive residual, and all other residuals are relatively small. For example, for Antiracist at Time 1 the residual for Oblivious is -3.00 and the residual for Fearful Guilt is 3.19. This pattern suggests that for each category at Time 1, the tendency of more students moving into a particular category is of the same strength as is the tendency of fewer students moving into a particular (different) category.

Table 5.

Standardized Residuals with PCRW Type at Entrance (Rows) and End of Year (Columns)

| Time 2 Type |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time1 | Oblivious | Empathic but Unaccountable | Antiracist | Fearful Guilt | Insensitive and Afraid |

| Oblivious | 0 | 1.58 | -3.40* | −2.50* | 4.99* |

| Empathic but Unaccountable | 0.04 | 0 | 2.53* | −.54 | −2.44 |

| Antiracist | −3.00* | 1.15 | 0 | 3.19* | −1.41 |

| Fearful Guilt | 0.34 | −0.86 | 1.98 | 0 | −1.71 |

| Insensitive and Afraid | 2.67* | −2.29 | −1.66 | 1.00 | 0 |

Note.

indicates standardized residuals greater in magnitude than 2.5.

A log-linear model of association was designed to capture the pattern found in the residuals of the quasi-independence model. The model of association continued to disregard the diagonals (“stayers”) but included one predictor variable for each row (Time 1 classification) where the predictors for cells in each row equaled 1 if the largest residual is negative, −1 if the largest residual is positive, and 0 if the residual is small (i.e., less than 1.64, which corresponds to a two tailed test with α = .10 ). The model of association fit the data well as indicated by the non-significant test for lack of fit ( , p = .10 ). This analysis provides further support to our finding that students starting in particular PCRW types had the tendency to move into certain PCRW types at the end of the year.

Odds ratios based on the model of association can be computed from either the fitted values (Table 4) or the estimated parameters representing the association (Table 6). For example, the odds of Insensitive and Afraid versus Antiracist at the end of the year given a student was in Oblivious at the beginning of the year are5

Table 6.

Estimated parameters representing the association between PCRW type at Time 1 and 2

| Time 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | Oblivious | Empathic but Unaccountable | Antiracist | Fearful Guilt | Insensitive and Afraid | Standard errors for non-zero parameters |

| Oblivious | - - - | 0 | −1.1609 | −1.1609 | 1.1609 | (0.5393) |

| Empathic but Unaccountable | 0 | - - - | 1.7492 | 0 | −1.7492 | (0.7843) |

| Antiracist | −1.1704 | 0 | - - - | 1.1704 | 0 | (0.5052) |

| Fearful Guilt | 0 | 0 | 1.2684 | - - - | −1.2684 | (0.7964) |

| Insensitive and Afraid | −1.1726 | 1.1726 | 0 | 0 | - - - | (0.5408) |

Note. See text for how to interpret this table and how to compute fitted/predicted odds ratios using these parameter estimates. Four decimal places were retained for accuracy in computing odds ratios.

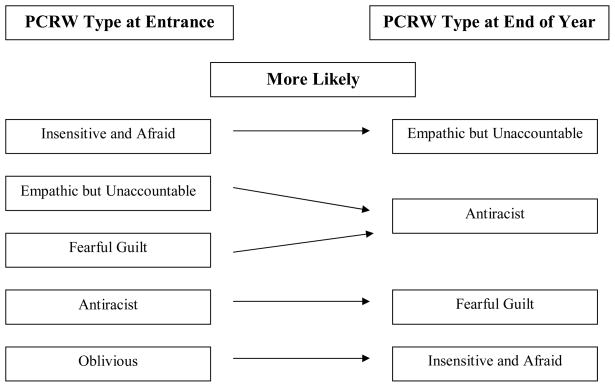

times larger than the odds given a student was Empathic but unaccountable at the beginning of the year. In other words, a student was more likely to move to Insensitive and Afraid if they started in Oblivious than if they started in Empathic but unaccountable. We can see the pattern of movement in Table 6 (parameters for association) better than in Table 4 (fitted counts). Loosely speaking, in Table 6 the positive numbers show where odds will tend to be larger relative to other categories (i.e., students moving into a column category) and the negative numbers show where odds will tend to be smaller (students not moving into a column category) than others. See Figure 3 for a graphic representation of PCRW type change.

Figure 3.

PCRW Type Change from Entrance to End of Year based on log-linear model.

Note: More likely refers to the large positive standardized residuals. Thus, if one started in a particular PCRW type at entrance (Time 1), they were more likely to end up in the specified type (as noted by the arrow) at the end of the year (Time 2).

Predicting College Diversity Engagement from PCRW Type at Entrance

To test whether and how PCRW types at entrance predicted diversity engagement activities throughout the year, we used multinomial logistic regression. In the regression models, PCRW type at entrance was the “response” variable and diversity engagement activities, assessed at the end of the year, served as the “predictors” in the statistical modeling. Given that PCRW type at entrance was assessed prior to diversity engagement, our results indicate possible ways in which PCRW type might predict engagement activities; however, our design cannot definitively indicate direction of influence. This analysis revealed that interracial friendships at the end of the year was the only variable predicted by initial PCRW type, , p < .01 (see Table 2). Diversity courses ( , p = .28) and diversity activities ( , p = .18) were not predicted by initial PCRW type and were dropped from the model. To further understand the association between PCRW type and interracial friendships, we computed odds ratios to examine which PCRW types at entrance were more likely to predict higher levels of interracial friendships at the conclusion of the year (see Table 3). Results indicated that individuals who had initial membership in Empathic but Unaccountable had greater odds of having more interracial friendships at the end of the year than individuals who had initial membership in the Oblivious, Fearful Guilt, or Insensitive and Afraid types. In addition, more interracial friendships related to greater odds of initial membership in the Antiracist type than in Insensitive and Afraid. Thus, initial membership in either the Empathic but Unaccountable or Antiracist types predicted greater interracial friendships at the end of the first year relative to the other types.

Predicting PCRW Type after Controlling for PCRW Type at Entrance

To address whether college diversity engagement during the course of the academic year predicted PCRW type at the end of the year, we used multinomial logistic regression. We intended to control for PCRW type at entrance. However, we ran into the problem of quasi-complete separation in the data, which indicated that the model was more complex than could be supported by the data (Agresti, 2007). Although not ideal, we fit a multinomial regression to PCRW type at the end of the year with only one diversity engagement variable (i.e., courses, activities, and friendships) in the models at a time (without controlling for PCRW at entrance). These analysis revealed that interracial friendships at the end of the year was the only variable able to predict PCRW type at the end of the year, , p < .01. This finding is not surprising and may be a function of the dependence of Time 1 and 2 PCRW types. Without being able to control, we are unable to know if the effect of interracial friendship is over and above this Time 1 and 2 association. In addition, diversity courses ( , p = .10) and diversity activities , p = .06 were not significant predictors of Time 2 PCRW type.

Discussion

This investigation advances our understanding of the ways in which PCRW types are linked to first-year university students’ diversity attitudes and engagement during the course of an academic year. Specifically, our findings indicate that (a) both the diversity attitudes of universal diverse orientation and unawareness of racial privilege explained PCRW type at entrance, and these associations offer further construct validity for the PCRW types; (b) particular PCRW types at entrance explained participation in cross-racial friendships, but did not explain participation in formal diversity experiences, such as courses and activities, at the end of the year; (c) PCRW type, while generally stable, may change during the course of the year; and (d) for those students (almost half of the sample) whose PCRW type changed, specific patterns emerged that are both desirable and undesirable. We were unable to examine what factors explained PCRW type at the end of the year while controlling for PCRW type at entrance, because our model was more complex than could be supported by our data.

PCRW Types at Entrance

Surprisingly, pre-college background characteristics such as gender, neighborhood wealth and poverty levels, high school and neighborhood racial composition, and high school interracial friendships did not explain PCRW type at entrance. Inconsistent with previous research, gender did not significantly explain PCRW types, which might be accounted for by the timing of our assessment at college entrance. Future research should explore the possibility that gender might not be a critical factor in PCRW type at the beginning of the year, but instead becomes relevant through socialization experiences during the course of college.

Although census data provide a more contextual view of the participants with regard to racial composition and wealth/poverty levels of their home environments and previous research suggests that neighborhood context affects some racial attitudes (e.g., Oliver & Mendelberg, 2000), racial diversity in home environments in this case did not explain PCRW type at college entrance. Scholars (e.g., Bonilla-Silva, 2006) have argued that racial diversity in neighborhoods does not necessarily result in increased cross-racial interactions. Future research might address participants’ perceptions of racial diversity in their home neighborhoods and compare these with actual census data to understand what additional factors contribute to close interracial friendships. Similarly, increased diversity in students’ high schools (i.e., greater exposure to racial and ethnic minorities) might still result in segregated spaces within high schools so that White students do not interact with racialized minority students. Qualitative findings among a sample of Midwestern, White undergraduates suggest, for instance, that even those in racially diverse high schools had few opportunities for meaningful cross-racial interactions through “tracking” practices (Spanierman, Oh et al., 2008). In addition to tracking in schools, Bonilla-Silva (2006) also suggests that Whites might engage in self-segregation or racialized interactions, such as stereotyping, that preclude close friendships with people of color.

In the current investigation we found that students’ self-report data on their interracial friendships in high school also was not related to PCRW type. Bonilla-Silva (2006) suggests that White students, when asked about cross-racial friendships, tend to define friendship broadly enough to include limited, superficial relationships that would not provide the type of sustained and intimate contact that facilitates attitude change. Moreover, Feagin and O’Brien (2003) note that when responding to surveys White individuals tend to over-report their close friendships with Black people. Clearly, better methods of assessment must be identified to determine how prior interracial friendships explain PCRW types.

Although background characteristics did not contribute to our understanding of PCRW types at entrance, we found that diversity attitudes did explain type. In particular, both universal diverse orientation and unawareness of racial privilege were relevant to PCRW type. More specifically, universal diverse orientation differentiated Empathic but Unaccountable as well as Antiracist types from most other types, whereas unawareness of racial privilege distinguished Insensitive and Afraid and Oblivious from most other types. Taken together, these findings suggest that both diversity appreciation and a critical consciousness of White privilege are important for understanding the nuances between PCRW types. As one might expect, diversity appreciation is linked to more desirable types and unawareness of racial privilege is linked to less desirable types, thus providing additional construct validity to the PCRW. Further research might explore the direction of influence between these constructs, as well as how other relevant constructs such as social dominance orientation (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999) or modern racist attitudes (McConahay, 1986) might also relate to the PCRW types.

With regard to whether or not PCRW types at entrance explained student diversity engagement throughout the year, our findings were mixed. PCRW types at entrance explained informal diversity engagement (i.e., interracial friendships) over the year but did not explain participation in formal diversity engagement (i.e., diversity courses and activities). As noted above, cross-racial friendships during high school were not relevant to PCRW type at entrance. It is possible that the retrospective, distal nature of high school friendships might account for this distinction. Moreover, we cautiously interpret the finding that cross-racial friendships during the first year of college significantly explain PCRW type at the end of the year in light of the problematic nature of self-reported cross-racial friendships. To understand the significance of interracial friendships during college, as compared to diversity courses and activities, we speculate that interracial friendships are more relevant to affective responses to racism than diversity courses or other formal activities. The latter activities might be more relevant to cognitive racial attitudes. Pettigrew (1998) argued that interracial friendships generate empathy for the out-group which is consistent with our results. In particular, our findings indicated that initial membership in the Empathic but Unaccountable and Antiracist types, both high in White empathy coupled with low White fear, explained engagement in interracial friendships at the end of the year. Apparently, the high White empathy / low White Fear combination, regardless of guilt, is most important in explaining interracial friendships. Although we were unable to test this notion, we speculate that interracial friendships throughout the year would in turn promote increased levels of White empathy, reflecting a cyclical nature between interracial friendships and White empathy. Future research should examine this hypothesis, as well as address varying conditions put forth by Allport (1979) regarding contact theory. Finally, the literature suggests that both formal and informal diversity engagement are important to prejudice reduction and other diversity factors (see Engberg, 2004). Our findings supported the literature regarding informal diversity engagement, but were inconsistent with regard to formal diversity engagement in courses and activities during the first year of college. Thus, future research might assess diversity courses and activities beyond the first year, when students have had greater opportunities to engage in elective courses and other formal campus activities.

PCRW Type Change during the Course of the Year

While we learned that PCRW types are relatively stable, we also found that students can change type, for better or worse. Specifically, we found that 45% of the participants changed PCRW types during the course of the academic year. As depicted in Figure 3, we evidenced a number of changes in the desired direction: Empathic but Unaccountable and Fearful Guilt both were most likely to move to the Antiracist type, and even the least culturally sensitive type, Insensitive and Afraid, was more likely to move to a more desirable type, Empathic but Unaccountable. However, our findings also suggest movement in an undesired direction in which those in the Oblivious type were more likely to move into Insensitive and Afraid than other types. Perhaps this finding can be explained by the sociological research on perceived threat and group position that indicates Whites’ negative attitudes toward people of color increase as perceived competition for resources increases (c.f., Bobo, 1999). Thus, if White students come to college from sheltered backgrounds where they had little exposure to people of color, they might experience increased threat upon entrance to college where there is a larger proportion of racial minorities (and where they are competing for the positive attention of professors and other campus resources). Another explanation relates to white racial identity development. Helms (1990) has suggested that when confronted with cognitive dissonance (e.g., discovering that one has participated in a racist system) and painful emotions, some Whites develop White superiority beliefs (i.e., Reintegration status) to legitimize their thoughts and behaviors. Also in an undesired direction, some Antiracist participants changed type and they were more likely to move to Fearful Guilt than other types. Future research should examine what types of experiences contribute to this negative change. Specifically, research is needed to understand potential factors during the first year of college that result in a decrease in racial empathy along with a concomitant increase in irrational fear and mistrust of people of color. Moreover, empirical research is warranted to better understand the kinds of experiences that result in the Antiracist type. Even though many participants changed PCRW types during the first year of college, more than half of the participants did not change, which attests to the relative stability of the PCRW types. Further, this suggests that the typical first year experience at a large Midwestern state university does not necessarily influence White students’ affective responses to racism. Future research may explore what experiences do prompt PCRW type change, especially change from less desirable to more desirable types.

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Although results provide initial evidence for understanding the factors that explain psychosocial costs of racism types on multiple levels, the study is not without limitations. Because the present sample consists solely of Midwestern students at one historically White university, generalization to other samples is limited. Thus, future research should aim for multi-university samples with greater geographical dispersion. Additionally, the cluster solution identified in the current investigation was not identical to that found in previous samples; therefore, further research is needed to determine if the 5-cluster solution identified by Spanierman and colleagues (2006) is indeed the best interpretation of the constellations of costs. Although the college setting is appropriate for this investigation because it presents many of the facilitative conditions of the contact hypothesis (e.g., equal-status interactions), future research could extend beyond the university and examine PCRW types among community members.

A number of points could be addressed in future research. Because we did not find background characteristics to contribute significantly to PCRW types at entrance, future research should employ alternative measurement strategies. More accurate assessment of close, intimate cross-racial relationships (e.g., social network analysis) is warranted. Additionally, more specific data are needed with regard to the relevance of diversity courses and activities for White students. Researchers must identify the specific kinds of experiences (e.g., ethnic studies courses versus gender and women’s studies courses) under what conditions (e.g., racially diverse classrooms) and for whom (i.e., particular PCRW types) are most relevant and appropriate. For example, students reflecting the Antiracist type might benefit most from a challenging course that requires deep introspection about one’s White privilege and critical analysis of structural racism in society, whereas Oblivious students might need an introductory course to help them understand the social construction of race and acknowledge the existence of institutional racism. As mentioned above, our design did not allow us to understand the direction of influence between PCRW types and diversity attitudes (i.e., UDO and unawareness of racial privilege). We recommend longitudinal analyses that span the college experience.

In addition to quantitative research, another useful approach would be to use qualitative (or mixed) methods to gain a deeper understanding of the nuances within and across PCRW types. Focus groups by PCRW types, for instance, could investigate more comprehensively participants’ lived experiences and help us to understand the development of PCRW types, particularly that of Antiracist. Qualitative methods also might identify potential linkages to prior conceptualizations of White racial identity development (e.g., Helms, 1990). Finally, we urge researchers to consider behavioral consequents of the PCRW types. For example, research could examine whether particular types are more likely to perpetrate racial microaggressions against people of color (see Sue et al., 2007) or, alternatively, if the Antiracist type is more likely to engage in social justice advocacy.

Practical Implications

This work is important for counseling psychologists, particularly those in college and university counseling settings, as well as student affairs professionals who design diversity outreach and intergroup dialogue programs. This research suggests that intervention efforts could be tailored to students from each PCRW type to enhance the effectiveness of these efforts. Further, students demonstrating the Antiracist type might be helpful as collaborators in the design of educational interventions for White students of other types. Additionally, as counseling psychologists broaden their roles in institutions of higher education, serving as advisors to administrative officials as they respond comprehensively and systemically to hate crimes and bias incidents, rather than episodically and imprecisely, this research suggests the relevance of a multifaceted and comprehensive approach to educating White students about power and privilege. Comprehensive efforts must address not only the content and design of campus diversity practices that permeate the lives of students and impact their educational experiences, but also the changes these programs allege they make in the lives of White students. White self-segregation on campuses must be addressed, as meaningful dialogue with other groups is essential in efforts to enhance racial empathy and thus develop attitudes indicative of the Antiracist type. Administrators must pay particular attention to promoting not only universal diverse orientations among students, but also to fostering greater awareness and critical consciousness among Whites about White privilege. Moreover, because of the importance of interracial friendships in our findings, perhaps one of the key benefits of diversity courses and activities for White students is cultivating skills in forming and maintaining interracial friendships.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded in part by a grant awarded to the first author from the Center on Democracy in a Multiracial Society at the University of Illinois, and was completed while the second author was a predoctoral trainee in the Quantitative Methods Program of the Department of Psychology, supported by a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Training Grant PHS 2 T32 MH014257 (awarded to M. Regenwetter). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NIMH.

We wish to thank D. Anthony Clark, Paul Poteat, Helen Neville, and Amanda Beer for their helpful feedback.

Footnotes

Term borrowed from Eduardo Bonilla Silva, as cited in David Roediger (2005).

This term refers to White students’ opposition to campus diversity initiatives. White backlash can be direct, such as opposing efforts to increase the number of racial minority students or require diversity courses (see News and Views: The White Student Backlash at SUNY Binghamton, December 1998). It can also be indirect, such as participating in racist-themed parties (e.g., Ghetto Fabulous, Tacos and Tequila, and so forth).

Due to unequal sample sizes, we used the Aspin-Welch-Satterthwaite df to adjust for possible unequal variances; this resulted in non-integer values (Toothaker & Miller, 1996).

This is equivalent to testing independence between the rows and columns.

The odds on the far left of the equation were computed using the fitted values in Table 4; the odds in the middle were computed using the parameter estimates in Table 6.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/cou.

References

- Agresti A. An introduction to categorical data analysis. 2. New York: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW. The nature of prejudice (25th anniversary edition) New York: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CJ, Rutkowski L. Multinomial logistic regression. In: Osborne J, editor. Best practices in quantitative methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. pp. 390–409. [Google Scholar]

- Astin A. What matters in college: Four critical years revisited. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bobo LD. Prejudice as group position: Microfoundations of a sociological approach to racism and race relations. Journal of Social Issues. 1999;55:445–472. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E. Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. 2. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bowser BP, Hunt RG, editors. Impacts of racism on White Americans. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Case KA. Raising White privilege awareness and reducing racial prejudice: Assessing diversity course effectiveness. Teaching of Psychology. 2007;34:231–235. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Conoley CW, King J, Rollins D, Rivera S, Veve M. Predictors of racial prejudice in White American counseling students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2006;34:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Engberg ME. Improving intergroup relations in higher education: A critical examination of the influence of educational interventions on racial bias. Review of Educational Research. 2004;74:473–524. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR, O’Brien E. White men on race: Power, privilege, and the shaping of cultural consciousness. Beacon, Massachusetts: Beacon Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR, Vera H. White racism. New York: Routledge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes JN, Miville ML, Mohr JJ, Sedlacek WE, Gretchen D. Factor structure and short form of the Miville-Guzman Universality-Diversity Scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2000;33:157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman DJ. Promoting diversity and social justice: Educating people from privileged groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Great Schools: The parent’s guide to K-12 Success. Retrieved March, 2008 from http://www.greatschools.net.

- Helms JE. Black and White racial identity: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Greenwood Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D. Cluster analysis in family psychology research. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:121–131. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illinois State Board of Education E-Report Card Public Site. Retrieved March, 2008 from http://webprod.isbe.net/ereportcard/publicsite/getSearchCriteria.aspx.

- Karp JB. The emotional impact and a model for changing racist attitudes. In: Bowser BJ, Hunt RG, editors. Impacts of racism on White Americans. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1981. pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kivel P. Uprooting racism: How White people can work for racial justice. Philadelphia, PA: New Society Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence SM, Bunche T. Feeling and dealing: Teaching White students about racial privilege. Teaching and Teacher Education. 1996;12:531–542. [Google Scholar]

- Lucal B. Oppression and privilege: Toward a relational conceptualization of race. Teaching Sociology. 1996;24:245–255. [Google Scholar]

- McConahay JB. Modern racism, ambivalence, and the Modern Racism Scale. In: Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, editors. Prejudice, discrimination, and racism. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 91–125. [Google Scholar]

- Miville ML, Gelso CJ, Pannu R, Liu W, Touradji P, Holloway P, Fuertes J. Appreciating similarities and valuing differences: The Miville-Guzman Universality-Diversity Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46:291–307. [Google Scholar]

- Neville HA, Lilly RL, Duran G, Lee RM, Browne L. Construction and initial validation of the Color-blind Racial Attitudes Scale (CoBRAS) Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2000;47:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Neville HA, Low KSD, Liao H, Walters JM, Landrum-Brown J. Color-blind racial ideology: Testing a context-based legitimizing ideology model. 2007. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- News and Views: The White Student Backlash at SUNY-Binghamton. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 1998;20:63. Retrieved October 20, 2008, from Ethnic NewsWatch (ENW) database. (Document ID: 494189961) [Google Scholar]

- Oliver EJ, Mendelberg T. Reconsidering the environmental determinants of White racial attitudes. American Journal of Political Science. 2000;44:574–589. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF. The mental health impact. In: Bowser BJ, Hunt RG, editors. Impacts of racism on White Americans. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1981. pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF. Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:65–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Spanierman LB. Further validation of the Psychosocial Costs of Racism to Whites Scale among a sample of employed adults. The Counseling Psychologist. 2008;36:871–894. [Google Scholar]

- Roediger D. What’s wrong with these pictures? Race, narratives of admission, and the liberal self-representations of historically white colleges and universities. Journal of Law and Policy. 2005;18:203–222. [Google Scholar]