Abstract

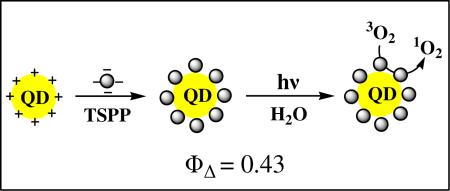

Water-soluble quantum dot - organic dye nanocomposites have been prepared via electrostatic interaction. We used CdTe quantum dots with diameters up to 3.4 nm, 2-aminoethanthiol as a stabilizer, and meso-tetra (4-sulfonatophenyl) porphine dihydrochloride (TSPP) as an organic dye. The photophysical properties of the nanocomposite have been investigated. The fluorescence of the parent CdTe quantum dot is largely suppressed. Instead, indirect excitation of the TSPP moiety leads to production of singlet oxygen with a quantum yield of 0.43. The nanocomposite is sufficiently photostable for biological applications.

Colloidal semiconductor nanocrystals (Quantum Dots, QDs) can provide three-dimensional (3D) architectures and have attracted widespread interest, since their nano-size physical properties are quite different from those of bulk materials.1 QDs photoluminescence can be size-tuned to improve spectral overlap with a particular acceptor, and having several acceptors interact with a single QDs donor substantially improves fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) efficiency. Retaining the small probe size is critical for successful in vivo applications since large-sized probes significantly reduce biostability, diffusion, and circulation processes, and increase undesired nonspecific binding.2 The small size of QDs is valuable for enhancing biological targeting efficiency and specificity.3

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an emerging modality for the treatment of a variety of oncological, dermatological, and other types of cancer.4 Singlet oxygen (1O2) is believed to be a major cyctotoxic species in this process. There have been several reports of nanoparticles as carriers for singlet oxygen photosensitizers.5-7 Nanoparticles can be ideal carriers of photosensitizer molecules for PDT. Moreover, some nanomaterials can generate singlet oxygen.8,9 Although this area has not received as much attention as the application of nanomaterials to electronics or catalysis, it represents a promising route to overcoming many of the difficulties associated with traditional PDT.10 Studies of electron transfer between QDs and organic dyes have recently attracted attention as well.11 Burda et al. have reported that a CdSe QD-sensitizer hybrid is able produce singlet oxygen via a FRET mechanism.7 However, this species was not soluble in water, thus limiting biological applications. Furthermore, no quantum yields for singlet oxygen production for any QD-organic dye nanocomposites have been published to date. Water-soluble species with a high 1O2 quantum yield are critical for artificial biocompatibility materials used as drug delivery carriers, and in vivo imaging. A cyclometalated Ir-complex type sensitizier12 attached to a CdSe/ZnS QD has also just been reported; however, in this system, the Ir complex was directly excited.13

We report herein the preparation of water-soluble QDs, using Meso-Tetra (4-sulfonatophenyl) Porphine Dihydrochloride (TSPP) as a photosensitizer, bound to CdTe nanocrystals via electrostatic interactions. The advantage of the electrostatic approach used in our work is that it allows control over the assembly behavior in solution.14

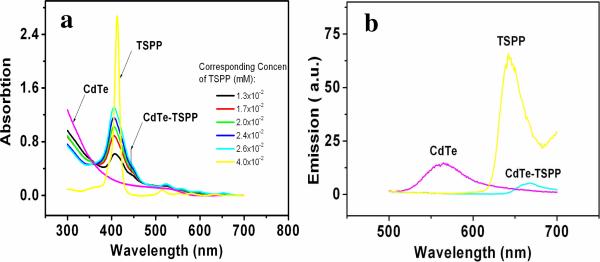

The CdTe QDs were synthesized with 2-aminoethanethiol as surface stabilizer. Synthesis of yellow photofluorescence CdTe nanocrystal was performed via a modified protocol adopted from the literature.15 The CdTe QDs revealed size-dependent luminescence with maxima at 560 nm. In a typical assay, the UV-vis spectra of QD-TSPP nanocomposites shifted slightly to the blue region,compared with free TSPP (Figure 1a). This could be surface caused by surface plasma changes as TSPP deposited on the of the QDs aggregates.16 The UV-vis peak of CdTe-TSPP nanocomposites increased with the concentration of added TSPP.Immediate aggregation was observed when the concentration of TSPP reached 6×10-2 mM. There is no obvious increase in the absorption peak of the QDs after combination with TSPP. The extinction coefficient of TSPP at 355 nm is very small. After TSPP was deposited on the QDs surface, the extinction coefficient of the nanocomposite at 355 nm increased significantly (almost tenfold) to 18300 M-1. The emission intensity of CdTe-TSPP nanocomposites decreased strongly when TSPP was deposited on the CdTe surface, suggesting energy transfer to the TSPP moiety (Fig.1). Interestingly, an absorption shift to 670 nm occurs concurrently with this energy transfer.

Figure 1a.

UV-vis spectra for the fabrication of CdTe with TSPP in 0.1 M pH 7.0 phosphate buffer solution. Spectrum 1(yellow) corresponds to the free TSPP (4×10-2 mM), while spectrum 2 (pink) corresponds to CdTe nanocrystals. The other spectra show formation of the CdTe-TSPP composite. 1b. Emission spectra of CdTe, TSPP and CdTe-TSPP nanocomposites, respectively. Excitation wavelength: 400 nm.

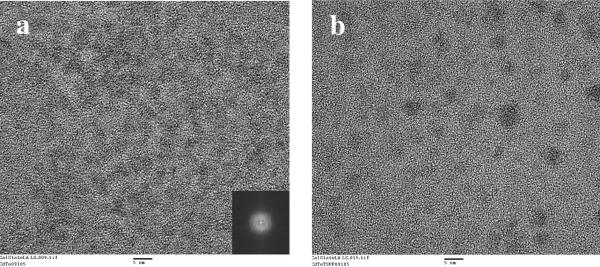

High resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) was used to characterize the structures of the processed particles and composites as shown in Figure 2. The main diameter of the CdTe core determined by TEM was 3.4 nm (with a standard deviation of 1.2 nm). Varying electron diffractive patterns were observed. A representative TEM image of the processed CdTe-TSPP composites showed sizes ranging from 6 to 8 nm. Magnification of these composites did not reveal the presence of aggregated clusters. However, no obvious electron diffractive patterns were present. We attribute these observations to enhanced packing passivation of the composites achieved due to the organic dye deposited on the nanocrystal surface.

Figure 2.

High resolution TEM image of CdTe nanocrystals(10-3 mM), a), and CdTe-TSPP nanocomposites ( 10-3 mM CdTe with 10-2 mM TSPP), b). Scale bar is 5 nm.

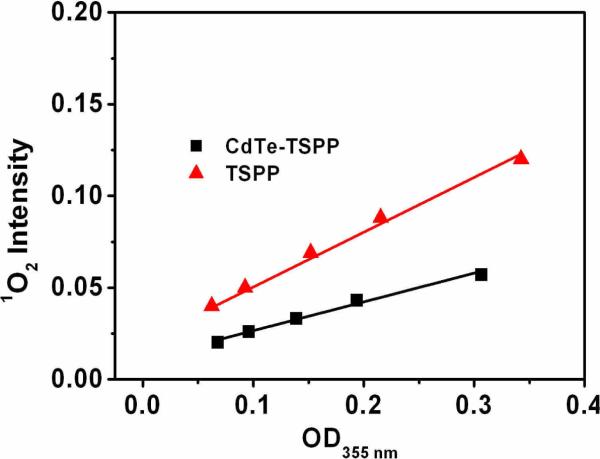

Upon excitation by near UV or visible light, the QD-TSPP composite does indeed produce singlet oxygen. To elucidate the mechanism of singlet oxygen production, we carried out detailed photophysical studies at 355 nm. Absorption of free TSPP is only about 10 % of that of the nanocomposite at this wavelength. Therefore, if an appreciable amount of singlet oxygen is detected at this wavelength, it must have been produced via excitation of the quantum dot. Excitation of the nanocomposite with a Nd:YAG laser at 355 nm does indeed produce the characteristic 1O2 emission signal in the near-infrared region. Addition of sodium azide to the solution leads to a sharp decline of the lifetime of this emission, demonstrating that the signal was indeed due to singlet oxygen. Singlet oxygen quantum yield (QY) measurements were carried out in D2O at 355 nm, using free TSPP as a reference. The singlet oxygen luminescence intensity was plotted vs. the optical density of the solution at the excitation wavelength. The ratio of the slopes thus obtained gives the ratio of the quantum yields of the nanocomposite vs. that of the reference compound (Fig. 3). The ratio of the QY of 1O2 of the CdTe-TSPP nanocomposites vs. free TSPP is 0.67 in D2O. Using the literature value of 0.64 for the singlet oxygen QY of TSPP, 17 we obtain a quantum yield for the production of singlet oxygen by the nanocomposite of 0.43 at 355 nm. No singlet oxygen was observed when the CdTe nanocrystal was excited in the absence of TSPP. This is similar to Donegá's report,18 but in contrast with the work of Burda et al. who observed a small amount (~ 5 %) of singlet oxygen formed directly from a CdSe QD.7 Since we obtained a QY of 0.43 for our nanocomposite at a wavelength where absorption of the free sensitizer is minimal, we suggest that singlet oxygen is produced via excitation of the QD followed by a FRET-type mechanism. Support for this hypothesis is obtained by the observation that the emission of the CdTe QD is greatly diminished after the TSPP is added to form the nanocomposite (Fig. 1b).

Figure 3.

Relative intensity of singlet oxygen production vs optical density of CdTe-TSPP nanocomposites or TSPP, excitation at 355 nm.

Photooxidation experiments were also carried out in the visible range (cut-off at 492 nm) to determine the stability of the nanocomposites and possible oxidation of the nanocomposites by 1O2. Methionine was oxidized to the corresponding sulfone, consistent with singlet oxygen production. The stability of the nanocomposite was also monitored during these reactions. At high concentrations (3.0×10-2 mM) of the nanocomposite, no decomposition was detected by 1H NMR spectroscopy over a period of 1 h. At lower concentrations, irradiation of the samples for 30 min did not lead to any changes, which is a time-frame sufficient for biological applications, such as PDT.19 Prolonged irradiation at low concentration resulted in a decrease in the absorption spectra of the CdTe-TSPP nanocomposite.

We have thus established that water-soluble quantum dot-organic dye nanocomposites can produce singlet oxygen with a quantum yield that is sufficiently high for biological applications. Such nanocomposites may therefore be used as model systems for living organism imaging and photodynamic therapy. Increasing the size of the QD should shift its absorption to the red region, and changing the length of the aminothiol stabilizer may affect the efficiency of FRET to the TSPP. Experiments to elucidate the magnitude of these effects are currently in progress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank for Ms. Carol Garland (California Institute of Technology) for help with the TEM experiment. We gratefully acknowledge support from the NSF-PREM program (Award No. 0351848) and from the NIH-NIGMS MBRS program (Award No. GM08101).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Detailed procedures regarding sample preparation and assay conditions for CdTe and CdTe-TSPP nanocomposites. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.a Alivisatos AP. Science. 1996;271:933. [Google Scholar]; b Michalet X, Pinaud FF, Bentolila LA, Tsay JM, Doose S, Li JJ, Sundaresan G, Wu AM, Gambhir SS, Weiss S. Science. 2005;307:538. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Burda C, Chen XB, Narayanan R, El-Sayed MA. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:1025. doi: 10.1021/cr030063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Chan WCW, Maxwell DJ, Gao XH, Bailey RE, Niu SM. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002;13:40. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gao XH, Yang L, Petros JA, Marshall FF, Simons JW, Niu SM. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2005;16:63. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Pouliquen D, Le Jeune JJ, Perdrisot R, Ermias A, jallet P. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 1991;9:275. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(91)90412-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Medintz IL, Clapp AR, Mattoussi H, Goldman ER, Fisher B, Mauro JM. Nat. Mater. 2003;2:630. doi: 10.1038/nmat961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bakalova R, Ohba H, Zhelev Z, Nagase T, Jose R, Ishikawa M, Baba Y. Nano Lett. 2001;4:1567. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Yokoyama M, Satoh A, Sakurai A, Okano T, Matsumura Y, Kakizoe T, Kataoka K. J. Control. Release. 1998;55:219. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(98)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Leroux J-C, Allémann E, Jaeghere FD, Doelker E, Gurny R. J. of Control. Release. 1996;39:339. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a Imahori H, Arimura M, Hanada T, Nishimura Y, Yamazaki I, Sakata Y, Fukuzumi S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:335. doi: 10.1021/ja002838s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Roy I, Ohulchanskyy TY, Pudavar HE, Bergey EJ, Oseroff AR, Morgan J, Dougherty TJ, Prasad PN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7860. doi: 10.1021/ja0343095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hone DC, Walker PI, Evans-Growing R, FitzGerald S, Beeby A, Chambrier I, Cook MJ, Russell DA. Langmuir. 2002;18:2985. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samia ACS, Chen XB, Burda C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:15736. doi: 10.1021/ja0386905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang SZ, Gao RM, Zhou FM, Selke M. J. Mater. Chem. 2004;14:487. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Argobast JW, Darmanyan AP, Foote CS, Diederich FN, Rubin Y, Diederich F, Alvarez M, Anz SJ, Whetten RL. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakalova R, Ohba H, Zhelev Z, Nagase T, Jose R, Ishikawa M, Ba Y. Nano Lett. 2004;4:1567. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a Clapp AR, Medintz IL, Fisher BR, Anderson GP, Mattoussi H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1242. doi: 10.1021/ja045676z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Clapp AR, Medintz IL, Mauro JM, Fisher BR, Bawendi MG, Mattoussi H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:301. doi: 10.1021/ja037088b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mattoussi H, Mauro JM, Goldman ER, Anderson GP, Sundar VC, Mikulec FV, Bawendi MG. J.Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:12142. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao RM, Ho DG, Hernandez B, Selke M, Murphy D, Djurovich P, Thompson ME. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:14828. doi: 10.1021/ja0280729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsieh JM, Ho ML, Wu PW, Chou PT, Tsai TT, Chi Y. Chem. Comm. 2006:615. doi: 10.1039/b517368j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelid DM, Zilbermann I, Anderson G, Kotov NA, Tagmatarchis N, Prato M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:14340. doi: 10.1021/ja048065f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a Gao MY, Kirstein S, Möhwald H, Rogach AL, Kornowski RA, Eychmüller A, Weller H. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:8360. [Google Scholar]; b Zhang H, Zhou Z, Yang B, Gao MY. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107:8. [Google Scholar]; c Zhang H, Cui ZC, Wang Y, Zhang K, Ji X, Lu CL, Yang B, Gao MY. Adv. Mater. 2003;15:777. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo YH, Huang JG, Ichinose I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:8296. doi: 10.1021/ja052189q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davila J, Harriman A. Photochem. Photobio. 1990;51:9. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1990.tb01678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wuister SF, Swart I, Driel FV, Hickey SG, Donegá CDM. Nano Lett. 2003;3:503. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konan YN, Guny R, Allemann E. J. Photochem. Photobio. B. 2002;66:89. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.