Abstract

The marine macrolide bryostatin 7 is prepared in 20 steps (longest linear sequence) and 36 total steps. A total of 5 C-C bonds are formed using hydrogenative methods. The present approach represents the most concise synthesis of any bryostatin reported, to date, setting the stage for practical syntheses of simplified functional analogues.

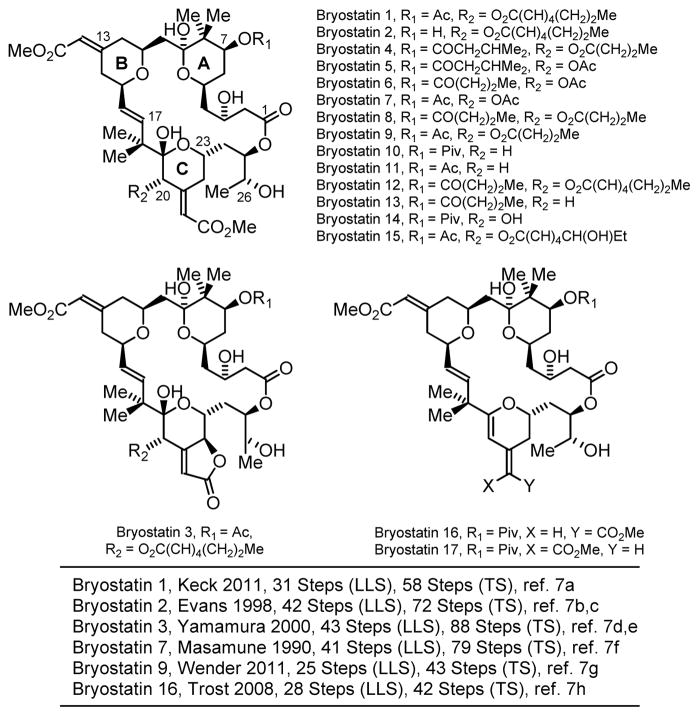

The bryostatins are a family of 20 marine natural products originally isolated from the bryozoan Bugula neritina1 that possess a polyacetate backbone and differ largely on the basis of substitution at C7 and C20 (Figure 1).2 The bryostatins display diverse biological effects, including antineoplastic activity, immunopotentiating activity, restoration of apoptotic function, and the ability to act synergistically with other chemotherapeutic agents.3 Neurological effects also are evident, including activity against Alzheimer’s disease,4 neural growth and repair and the reversal of stroke damage,5 as well as memory enhancement.6

Figure 1.

Bryostatins 1–17 and prior total syntheses.a

aSee supporting information for a graphical summary of prior syntheses.

As their natural abundance is insufficient to advance clinical and biochemical studies, the bryostatins have emerged as a vibrant testing ground for polyketide construction. To date, total syntheses of bryostatin 1 (Keck, 2011),7a bryostatin 2 (Evans, 1998),7b,c bryostatin 3 (Yamamura, 2000),7d,e bryostatin 7 (Masamune, 1990),7f bryostatin 9 (Wender, 2011)7g and bryostatin 16 (Trost, 2008)7h have been reported. A formal synthesis of bryostatin 7 (Hale, 2006)8a and total syntheses of C20-epi-bryostatin 7 (Trost, 2010)8b and C20-deoxybryostatin (Thomas, 2011)8c have been disclosed. In efforts led by Wender9,10 and Keck,11 simplified bryostatin analogues that retain high potency have been identified.

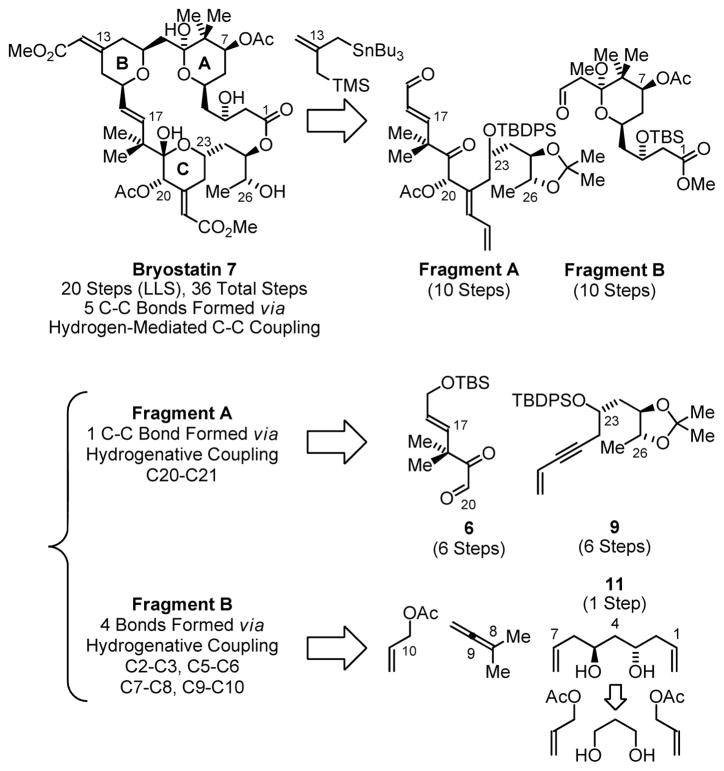

Given the longstanding challenges associated with defining concise routes to the bryostatins, these natural products were deemed an ideal vehicle to benchmark the utility of the C-C bond forming hydrogenations developed in our laboratory.12 Retrosynthetically, a convergent assembly of the bryostatin 7 core from Fragments A and B employing the Keck-Yu pyran annulation13,14 and Yamaguchi macrolactonization15 was envisioned. For the synthesis of Fragment A, hydrogen-mediated reductive coupling of conjugated glyoxal 6 and enyne 9 appeared strategic, as the key C20-C21 bond would be formed with control of the C20 carbinol stereochemistry and C21 olefin geometry.16 The planned synthesis of Fragment B, which incorporates the bryostatin A-ring, takes advantage of three transfer hydrogenative processes: enantioselective double allylation of 1,3-propanediol to furnish the C2-symmetric diol 11,17a subsequent aldehyde tert-prenylation17b to establish the C7 carbinol stereochemistry and install the C8 gem-dimethyl moiety and, finally, allylation17c,d at C9 to introduce the C11 aldehyde. The feasibility of these fragment syntheses has been established in model systems (Scheme 1).16,17e

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analysis of bryostatin 7 illustrating C-C bonds formed via hydrogenative coupling.

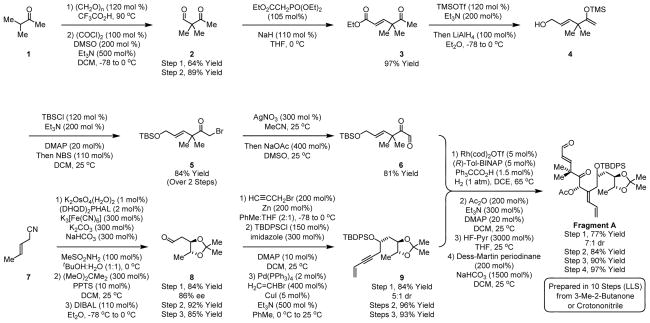

The synthesis of Fragment A begins with the hydroxymethylation of 3-methyl-2-butanone 1 to furnish the aldol product in accordance with the literature procedure.18 Moffatt-Swern oxidation of the aldol product provides ketoaldehyde 2, which upon Horner-Wadworth-Emmons olefination delivers the α,β-unsaturated ester 3. All compounds up to this point are isolated by vacuum distillation, expediting access to large quantities of material. Conversion of 3 to the enol silane followed by addition of LiAlH4 to the reaction mixture directly provides the allylic alcohol 4.19 Treatment of crude allylic alcohol 4 with tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride followed N-bromosuccinimide provides the α-bromoketone 5 in 84% yield over the two-step sequence from α,β-unsaturated ester 3. Finally, Kornblum oxidation of α-bromoketone 5 delivers the glyoxal 6 (Scheme 2).20

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Fragment A via hydrogen-mediated reductive coupling of glyoxal 6 and 1,3-enyne 9.a

aIndicated yields are of material isolated by silica gel chromatography or distillation. See supporting information for experimental details.

Preparation of the requisite 1,3-enyne 9 takes advantage of the Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation of crotononitrile 7, which provides the diol in 86% enantiomeric excess.21 The diol is converted to the acetonide and exposed to diisobutylaluminum hydride to provide the aldehyde 8, which is a known compound previously prepared using a 6-step sequence.22 Chelation controlled propargylzinc addition converts aldehyde 8 to the homopropargylic alcohol, which is formed as a 5:1 mixture of diastereomers.22 As described in the supporting information, the minor isomer is easily converted to the desired epimer using a Mitsunobu inversion protocol. The homopropargylic alcohol is converted to the TBDPS ether and subjected to Sonogashira coupling to deliver the 1,3-enyne 9 (Scheme 2).

To complete the synthesis of Fragment A, the glyoxal 6 and 1,3-enyne 9 are subjected to hydrogen-mediated reductive coupling to furnish the α-hydroxyketone in 77% yield as a 7:1 mixture of diastereomers.16 Notably, although the coupling product incorporates multiple points of unsaturation, over-reduction is not observed under the conditions of hydrogenative coupling. Exposure of α-hydroxyketone to acetic anhydride provides the acetate. Selective deprotection of the allylic TBS-ether in the presence of the TBDPS ether, which is accomplished using HF-pyridine, provides the allylic alcohol. Finally, oxidation of allylic alcohol delivers the enal, Fragment A, in a total of 10 steps from 3-methyl-2-butanone 1 or crotononitrile 7 (Scheme 2).

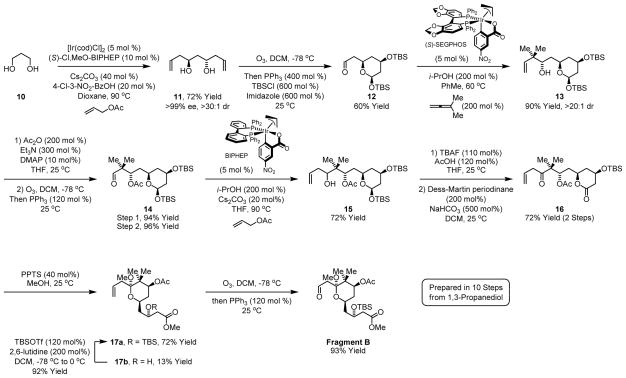

Efforts toward Fragment B begin with allyl acetate mediated double allylation of 1,3-propanediol 1017a,e to form C2-symmetric diol 11. This process employs an iridium catalyst generated in situ from [Ir(cod)Cl]2, allyl acetate, 4-chloro-3-nitrobenzoic acid and (S)-Cl,MeO-BIPHEP. Because the minor enantiomer of the mono-allylated intermediate is converted to the meso-diastereomer,23 diol 11 is obtained as a single enantiomer, as determined by chiral stationary phase HPLC analysis. Previously, the mono-TBS ether of diol 11 was prepared in 7 steps from 1,3-propanediol through iterative use of Brown’s reagent for carbonyl allylation.24a Alternatively, a four step protocol for the preparation diol 11 from acetylacetone is described.24b Ozonolysis of diol 11 delivers an unstable lactol, which is protected in situ as the bis-TBS ether to provide aldehyde 12 as a single isomer. Transfer hydrogenation of aldehyde 12 in the presence of 1,1-dimethylallene promotes tert-prenylation17b to form neopentyl alcohol 13. In this process, isopropanol serves as the hydrogen donor and the discrete iridium complex prepared from [Ir(cod)Cl]2, allyl acetate, m-nitrobenzoic acid and (S)-SEGPHOS25 is used as catalyst. Notably, complete levels of catalyst directed diastereoselectivity are observed.26 Exposure of neopentyl alcohol 13 to acetic anhydride followed by ozonolysis provides β-acetoxy aldehyde 14. Reductive coupling of aldehyde 14 and allyl acetate under transfer hydrogenation conditions results in the formation of homoallylic alcohol 15. As the stereochemistry of this addition is irrelevant, an achiral iridium complex derived from [Ir(cod)Cl]2, allyl acetate, m-nitrobenzoic acid and BIPHEP is employed as catalyst. Selective removal of the glycosidic silyl ether followed by concomitant Dess-Martin oxidation of the lactol and homoallylic alcohols provides β,γ-enone 16. Remarkably, treatment of a methanolic solution of 16 to pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate triggers sequential lactone ring opening followed by formation of the cyclic ketal 17a. Ozonolysis of 17a provides Fragment B in a total of 10 steps from 1,3-propanediol 10 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Fragment B employing multiple transfer hydrogenative C-C bond formations.a

aIndicated yields are of material isolated by silica gel chromatography. See supporting information for experimental details.

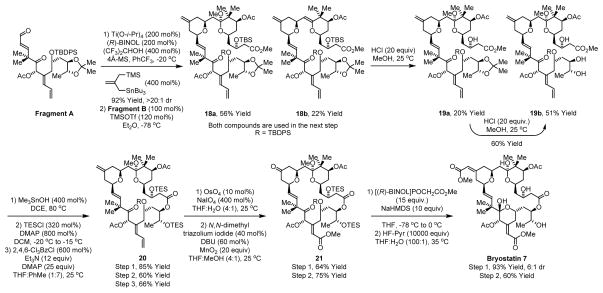

The union of Fragment A and Fragment B is achieved through Keck-Yu annulation to form the B-ring pyran.13,14 The desired adduct 18a is accompanied by the elimination product 18b, however, both compounds participate in acidic methanolysis to form triol 19b. Chemoselective hydrolysis of the C1 methyl ester in the presence of the C7 and C20 acetates employing trimethyltin hydroxide27 followed by selective TES-protection of the triol reveals a hydroxy acid, which upon Yamaguchi macrolactonization15 provides tetraene 20. Concomitant Johnson-Lemieux oxidation28 of the olefinic termini of tetraene 20 in the presence of the neopentyl olefin at C16-C17 installs both the Bring ketone and C-ring enal. Whereas Corey-Gilman oxidation of enal failed,29 the corresponding N-heterocyclic carbene promoted process provided the desired methyl ester 21 in good isolated yield.30 Finally, as practiced in prior syntheses,7a,b,c,d,g asymmetric olefination of the B-ring ketone using Fuji’s chiral phosphonate31 followed by global deprotection using HF-pyridine provides bryostatin 7 (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Union of Fragment A and Fragment B and total synthesis of bryostatin 7.a

aIndicated yields are of material isolated by silica gel chromatography. See supporting information for experimental details.

The present synthesis of bryostatin 7 is accomplished in 20 linear and 36 total steps,32 representing the most concise sequence to any bryostatin reported, to date. The concise nature of this approach can be attributed to the rapid assembly of key fragments A and B, as availed through application of C-C bond forming hydrogenations developed in our laboratory12 – a technology that has enabled dramatic simplification in the synthesis of other polyketide natural products.33 This work serves as a prelude to even shorter routes to the bryostatins and simplified functional analogues. More broadly, the merged redox-construction events central to this study speak to an emerging retrosynthetic paradigm, wherein C-C bond construction is accompanied by withdrawal of hydrogen.34,35

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Welch Foundation (F-0038), the NIH-NIGMS (RO1-GM093905) and the UT Austin, Center for Green Chemistry and Catalysis are acknowledged for financial support. Max Hansmann and Dr. Jin Haek Yang are acknowledged for skillful technical assistance

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, spectral, HPLC and GC data. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Pettit GR, Herald CL, Doubek DL, Herald DL, Arnold E, Clardy J. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6846.Recently, it was found that the natural product actually derives from a bacterial symbiont of B. neritina: Sudek S, Lopanik NB, Waggoner LE, Hildebrand M, Anderson C, Liu H, Patel A, Sherman DH, Haygood MG. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:67. doi: 10.1021/np060361d.

- 2.(a) Pettit GR. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:812. doi: 10.1021/np9604386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lopanik N, Gustafson KR, Lindquist N. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:1412. doi: 10.1021/np040007k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For selected reviews encompassing the biological properties of the bryostatins, see: Hale KJ, Hummersone MG, Manaviazar S, Frigerio M. Nat Prod Rep. 2002;19:413. doi: 10.1039/b009211h.Kortmansky J, Schwartz GK. Cancer Invest. 2003;21:924. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120025095.Wender PA, Baryza JL, Hilinski MK, Horan JC, Kan C, Verma VA. Beyond Natural Products: Synthetic Analogues of Bryostatin 1. In: Huang Z, editor. Drug Discovery Research: New Frontiers in the Post-Genomic Era. Wiley-VCH; Hoboken, NJ: 2007. pp. 127–162.

- 4.(a) Etcheberrigaray R, Tan M, Dewachter I, Kuiperi C, Van der Auwera I, Wera S, Qiao L, Bank B, Nelson TJ, Kozikowski AP, Van Leuven F, Alkon DL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403921101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Alkon DL, Sun MK, Nelson TJ. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:51. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun MK, Hongpaisan J, Nelson TJ, Alkon DL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805952105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Alkon DL, Epstein H, Kuzirian A, Bennett MC, Nelson TJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508001102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun MK, Alkon DL. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;512:43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For total syntheses of naturally occurring bryostatins, see: Bryostatin 1: Keck GE, Poudel YB, Cummins TJ, Rudra A, Covel JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:744. doi: 10.1021/ja110198y.Bryostatin 2: Evans DA, Carter PH, Carreira EM, Prunet JA, Charette AB, Lautens M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:2354. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980918)37:17<2354::AID-ANIE2354>3.0.CO;2-9.Evans DA, Carter PH, Carreira EM, Charette AB, Prunet JA, Lautens M. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:7540.Bryostatin 3: Ohmori K, Ogawa Y, Obitsu T, Ishikawa Y, Nishiyama S, Yamamura S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:2290.Ohmori K. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2004;77:875.Bryostatin 7: Kageyama M, Tamura T, Nantz M, Roberts JC, Somfai P, Whritenour DC, Masamune S. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:7407.Bryostatin 9: Wender PA, Schrier AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9228. doi: 10.1021/ja203034k.Bryostatin 16: Trost BM, Dong G. Nature. 2008;456:485. doi: 10.1038/nature07543.

- 8.(a) Manaviazar S, Frigerio M, Bhatia GS, Hummersone MG, Aliev AE, Hale KJ. Org Lett. 2006;8:4477. doi: 10.1021/ol061626i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM, Dong G. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:16403. doi: 10.1021/ja105129p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Green AP, Lee ATL, Thomas EJ. Chem Comm. 2011;47:7200. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12332g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For recent contributions to the primary literature, see: Wender PA, Verma VA. Org Lett. 2006;8:1893. doi: 10.1021/ol060457z.Wender PA, Horan JC. Org Lett. 2006;8:4581. doi: 10.1021/ol0618149.Wender PA, Horan JC, Verma VA. Org Lett. 2006;8:5299. doi: 10.1021/ol0620904.Wender PA, Verma VA. Org Lett. 2008;10:3331. doi: 10.1021/ol801235h.Wender PA, DeChristopher BA, Schreier AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6658. doi: 10.1021/ja8015632.

- 10.Reviews: Wender PA, Martin-Cantalejo Y, Carpenter AJ, Chiu A, De Brabander J, Harran PG, Jimenez JM, Koehler MFT, Lippa B, Morrison JA, Müller SG, Müller SN, Park CM, Shiozaki M, Siedenbiedel C, Skalitsky DJ, Tanaka M, Irie K. Pure Appl Chem. 1998;70:539.Wender PA, Hinkle KW, Koehler MFT, Lippa B. Med Res Rev. 1999;19:388. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(199909)19:5<388::aid-med6>3.0.co;2-h.Wender PA, Baryza JL, Brenner SE, Clarke MO, Gamber GG, Horan JC, Jessop TC, Kan C, Pattabiraman K, Williams TJ. Pure Appl Chem. 2003;75:143.(d) And reference 3c.

- 11.(a) Keck GE, Truong AP. Org Lett. 2005;7:2153. doi: 10.1021/ol050512o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Keck GE, Welch DS, Vivian PK. Org Lett. 2006;8:3667. doi: 10.1021/ol061173h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Keck GE, Welch DS, Poudel YB. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:8267. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.09.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Keck GE, Kraft MB, Truong AP, Li W, Sanchez CC, Kedei N, Lewin NE, Blumberg PM. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6660. doi: 10.1021/ja8022169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Keck GE, Poudel YB, Welch DS, Kraft MB, Truong AP, Stephens JC, Kedei N, Lewin NE, Blumberg PM. Org Lett. 2009;11:593. doi: 10.1021/ol8027253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Keck GE, Poudel YB, Rudra A, Stephens JC, Kedei N, Lewin NE, Peach ML, Blumburg PM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:4580. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For recent reviews on C-C bond forming hydrogenation and transfer hydrogenation, see: Patman RL, Bower JF, Kim IS, Krische MJ. Aldrichim Acta. 2008;41:95.Bower JF, Krische MJ. Top Organomet Chem. 2011;43:107. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-15334-1_5.

- 13.For the parent pyran annulation strategy: Keck GE, Covel JA, Schiff T, Yu T. Org Lett. 2002;4:1189. doi: 10.1021/ol025645d.Yu CM, Lee JY, So B, Hong J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:161. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020104)41:1<161::aid-anie161>3.0.co;2-n.

- 14.For application of this pyran annulation strategy to bryostatin 1, bryostatin 9 and related structures, see: Keck GA, Welch DS, Poudel YB. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:8267. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.09.094.and references 7a, 9 and 11

- 15.Inanaga J, Hirata K, Saeki H, Katsuki T, Yamaguchi M. Bull Soc Chem Jpn. 1979;52:1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho CW, Krische MJ. Org Lett. 2006;8:891. doi: 10.1021/ol052976s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Lu Y, Kim IS, Hassan A, Del Valle DJ, Krische MJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:5018. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Han SB, Kim IS, Han H, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6916. doi: 10.1021/ja902437k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kim IS, Ngai MY, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6340. doi: 10.1021/ja802001b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kim IS, Ngai MY, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14891. doi: 10.1021/ja805722e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lu Y, Krische MJ. Org Lett. 2009;11:3108. doi: 10.1021/ol901096d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trost BM, Yang H, Thiel OR, Frontier AJ, Brindle CS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2206. doi: 10.1021/ja067305j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.For a similar enolization-reduction sequence, see: Lovchik MA, Goeke A, Frater G. J Org Chem. 2007;72:2427. doi: 10.1021/jo062264v.

- 20.Kornblum N, Frazier HW. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:865. [Google Scholar]

- 21.AD-mix-β failed to provide complete conversion: Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Chem Rev. 1994;94:2483.

- 22.Almendros P, Rae A, Thomas EJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:9565. [Google Scholar]

- 23.For amplification of enantiomeric enrichment in the generation of C2-symmetric compounds: Kogure T, Eliel EL. J Org Chem. 1984;49:576.Midland MM, Gabriel J. J Org Chem. 1985;50:1143.

- 24.(a) Smith AB, III, Minbiole KP, Verhoest PR, Schelhaas M. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10942. doi: 10.1021/ja011604l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rychnovsky SD, Griesgraber G, Powers JP. Org Synth. 2000;77:1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.SEGPHOS: Saito T, Yokozawa T, Ishizaki T, Moroi T, Sayo N, Miura T, Kumobayashi H. Adv Synth Catal. 2001;343:264.

- 26.For selected examples of catalyst-directed diastereoselectivity, see: Minami N, Ko SS, Kishi Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:1109.Ko SY, Lee AWM, Masamune S, Reed LA, III, Sharpless KB, Walker FJ. Science. 1983;220:949. doi: 10.1126/science.220.4600.949.Kobayashi S, Ohtsubo A, Mukaiyama T. Chem Lett. 1991:831.Hammadi A, Nuzillard JM, Poulin JC, Kagan HB. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1992;3:1247.Doyle MP, Kalinin AV, Ene DG. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:8837.Trost BM, Calkins TL, Oertelt C, Zambrano J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:1713.Balskus EP, Jacobsen EN. Science. 2007;317:1736. doi: 10.1126/science.1146939.Han SB, Kong JR, Krische MJ. Org Lett. 2008;10:4133. doi: 10.1021/ol8018874.

- 27.Nicalaou KC, Estrada AA, Zak M, Lee SH, Safina BS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:1378. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.For examples of selective Johnson-Lemieux oxidation of terminal olefins in the presence of higher olefins, see: White JD, Kuntiyong P, Lee TH. Org Lett. 2006;8:6039. doi: 10.1021/ol062530r.BouzBouz S, Cossy J. Org Lett. 2003;5:3029. doi: 10.1021/ol034958l.

- 29.(a) Corey EJ, Gilman NW, Ganem BE. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:5616. [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey EJ, Katzenellenbogen JA, Gilman NW, Roman SA, Erickson BW. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:5618. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gilman NW. Chem Commun. 1971:733. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maki BE, Scheidt KA. Org Lett. 2008;10:4331. doi: 10.1021/ol8018488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.(a) Tanaka K, Ohta Y, Fuji K, Taga T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:4071. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tanaka K, Otsubo K, Fuji K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:3735. [Google Scholar]

- 32.A conventional step-counting formalism is employed wherein one step is defined as a “one-pot” procedure that does not require the removal and exchange of reaction solvent.

- 33.Han SB, Hassan A, Kim IS, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15559. doi: 10.1021/ja1082798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.“The ideal synthesis creates a complex skeleton… in a sequence only of successive construction reactions involving no intermediary refunctionalizations, and leading directly to the structure of the target, not only its skeleton but also its correctly placed functionality.” Hendrickson JB. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:5784.

- 35.For an overview of “redox economy” in organic synthesis, see: Baran PS, Hoffmann RW, Burns NZ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:2854. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806086.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.