Abstract

Yeast Los1p, the homolog of human exportin-t, mediates nuclear export of tRNA. Using fluorescence in situ hybridization, we could show that the export of some intronless tRNA species is not detectably affected by the disruption of LOS1. To find other factors that facilitate tRNA export, we performed a suppressor screen of a synthetically lethal los1 mutant and identified the essential translation elongation factor eEF-1A. Mutations in eEF-1A impaired nuclear export of all tRNAs tested, which included both spliced and intronless species. An even stronger defect in nuclear exit of tRNA was observed under conditions that inhibited tRNA aminoacylation. In all cases, inhibition of tRNA export led to nucleolar accumulation of mature tRNAs. Our data show that tRNA aminoacylation and eEF-1A are required for efficient nuclear tRNA export in yeast and suggest coordination between the protein translation and the nuclear tRNA processing and transport machineries.

Keywords: Nuclear export, LOS1, tRNA, eEF1A, aminoacylation

The presence of the nuclear envelope in eukaryotic cells as a barrier between the nucleus and the cytoplasm necessitates the continuous bidirectional transport of macromolecules through the nuclear pore complexes (for review, see Adam 1999). In particular, nuclear export of tRNA (for review, see Simos 1999; Simos and Hurt 1999; Wolin and Matera 1999, Grosshans et al. 2000) was shown many years ago to be a carrier-mediated and active transport process, sensitive to mutations that destabilize the conserved tRNA tertiary structure or severely impair its processing (Tobian et al. 1985). Recently, a member of the importin (karyopherin) β family was characterized as a nuclear export receptor for tRNA in vertebrates (Xpo-t; Arts et al. 1998a; Kutay et al. 1998) and in yeast (Los1p; Hellmuth et al. 1998; Sarkar and Hopper 1998). It is thought that Xpo-t interacts cooperatively with Ran–GTP and newly synthesized tRNAs in the nucleus, forming a ternary transport complex that can be translocated into the cytoplasm. Experiments with microinjections into Xenopus oocyte nuclei have shown that certain features of the tertiary structure of tRNA as well as maturation of its 5′ and 3′ ends are requirements for both association with Xpo-t and efficient nuclear export (Arts et al. 1998b; Lund and Dahlberg 1998; Lipowsky et al. 1999). Furthermore, it was found that tRNA aminoacylation can occur inside the nucleus of Xenopus oocytes and facilitate nuclear tRNA export (Lund and Dahlberg 1998). On the other hand, it has also been shown that non-aminoacylated tRNAs can bind with high affinity to Xpo-t (Arts et al. 1998b; Lipowsky et al. 1999). Nevertheless, these uncharged tRNAs were exported from the nucleus more slowly than the corresponding charged tRNAs (Arts et al. 1998b; Lipowsky et al. 1999).

Los1p is the homolog of Xpo-t in yeast and is likewise involved in the Ran–GTP-dependent nuclear export of tRNA (Hellmuth et al. 1998; Sarkar and Hopper 1998). However, disruption of the LOS1 gene does not cause any apparent growth defect (Hurt et al. 1987), suggesting that nuclear export of tRNA still continues in the absence of Los1p, at least to an extent that supports normal cell growth. Furthermore, we now show, using an in situ hybridization assay to localize specific tRNA species, that nuclear export of only a subset of tRNAs is affected in the los1 disruption mutant. We therefore set out to identify additional components of the tRNA export pathway(s) in yeast by isolating high-copy suppressors of a synthetically lethal los1 mutant. In this screen, we found the TEF1 gene, which codes for the essential protein translation factor eEF-1A (previously called EF-1α). tRNA localization could demonstrate that eEF-1A as well as tRNA aminoacylation are required for efficient nuclear tRNA export in yeast.

Results

Disruption of LOS1 impairs nuclear export of only a subset of tRNAs

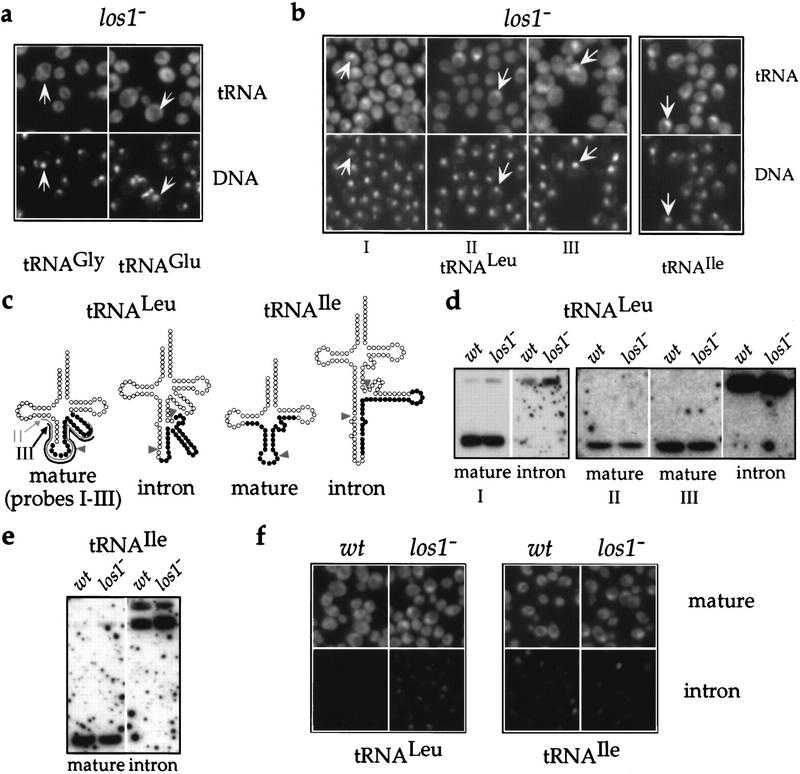

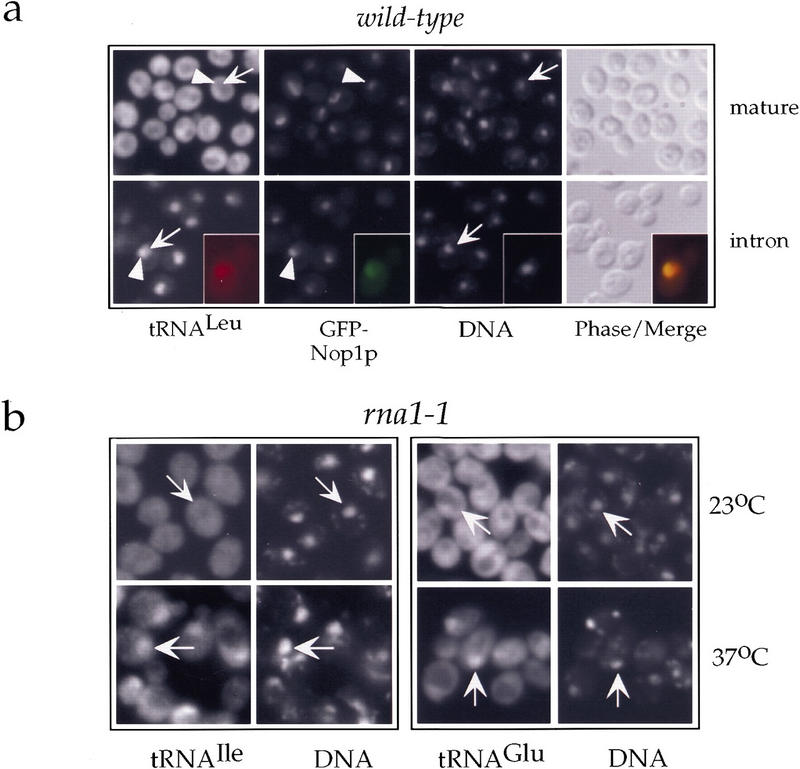

To study nuclear tRNA export in yeast, we set up a fluorescence in situ hybridization assay that, as recently shown (Bertrand et al. 1998; Sarkar and Hopper 1998), allows the localization of distinct tRNA species. As probes, we used Cy3-labeled DNA oligonucleotides complementary to the mature sequences of the tRNA species tRNALeu(CAA) and minor tRNAIle(UAU), which are encoded by intron-containing genes (Fig. 2c, below), as well as tRNAGlu(UUC) and tRNAGly(GCC), which are encoded by intronless genes. These probes were first tested in wild-type yeast cells and in all cases yielded a cytoplasmic signal (Fig. 1a, top; data not shown). The signal was specific for mature tRNA as it was largely excluded from vacuoles and nuclei, abolished by treatment with RNase and competed by yeast tRNA (data not shown). To test accessibility of the nucleus to our probes, we used oligonucleotides complementary to the intron sequence of pre-tRNALeu(CAA) or pre-tRNAIle(UAU) (Fig. 2c). As reported previously (Sarkar and Hopper 1998), the intron-containing pre-tRNAs were detected exclusively inside the nucleus (Fig. 1a, bottom). Moreover, colocalization with the GFP-tagged nucleolar protein Nop1p revealed that unspliced pre-tRNAs were found in both the nucleoplasm and the nucleolus (Fig. 1a, bottom and inset), in agreement with previous data that suggested nucleolar localization of pre-tRNA processing (Bertrand et al. 1998).

Figure 2.

Disruption of LOS1 causes nuclear accumulation of a subset of tRNA species. (a) Localization of tRNAGly(GCC) and tRNAGlu(UUC) in the los1− strain grown at 30°C. Representative cells are labeled by arrows that point to the nucleoplasmic space as judged by DAPI staining. (b) Localization of tRNALeu(CAA) (left) and tRNAIle(UAU) (right) in los1− cells grown at 30°C using the mature probes schematically depicted in c. Representative cells are labeled as in a.(c) Schematic representation of mature and intron-containing tRNALeu(CAA) and tRNAIle(UAU). Sequences that hybridize to the probes are indicated by solid circles. In the case of mature tRNALeu(CAA), solid circles represent the sequence hybridizing to probe I, whereas probes II and III are indicated by gray and black lines, respectively. Arrowheads point to splice sites. (d,e) Detection of tRNALeu(CAA) (d) and tRNAIle(UAU) (e) by Northern blot analysis. Total RNA was extracted from wild-type (wt) or los1− cells grown at 30°C. The probes used to detect the tRNAs are indicated below the panels. (d) Formamide (50%) or (e) no formamide were included in the hybridization buffer. (f) Mature and intron-containing tRNALeu(CAA) and tRNAIle(UAU) are localized in los1− and wild-type (wt) cells. Pictures within each box were taken at identical exposure times, that is, 120 msec for tRNALeu(CAA) and 600 msec for tRNAIle(UAU). Probe I was used to detect mature tRNALeu(CAA).

Figure 1.

A nuclear tRNA export assay in yeast on the basis of fluorescent in situ hybridization. (a) Localization of mature tRNALeu(CAA) (mature, top) and its corresponding unspliced precursor (intron, bottom) in the wild-type strain RS453 expressing GFP–Nop1p. DNA was visualized by staining with DAPI. The insets in the bottom panel show a single cell in which the signal for tRNA has been colored red and the signal for GFP–Nop1 green so that colocalization is shown by the yellow color upon merging. Representative cells are labeled by arrows that point to the nucleoplasmic space as judged by DAPI staining; arrowheads point to nucleoli as judged by the GFP–Nop1p signal. (b) Localization of tRNAIle(UAU) and tRNAGlu(UUC) in the thermosensitive rna1-1 strain grown at 23°C or shifted for 4 hr to 37°C as indicated. Representative cells are labeled by arrows that point to the nucleoplasmic space as judged by DAPI staining.

To test the applicability of our assay, we localized the aforementioned tRNA species in yeast mutants shown previously to be impaired in tRNA nuclear export such as the rna1-1 mutant (Sarkar and Hopper 1998) and a strain in which the LOS1 gene has been disrupted (los1−; Simos et al. 1996b). Analysis of the thermosensitive rna1-1 strain, which is defective in the Rna1p-mediated Ran-GTP hydrolysis, revealed intranuclear accumulation of all tested tRNAs upon shifting the cells to the restrictive temperature. This is shown in Figure 1b for tRNAIle, which is encoded by an intron-containing gene, and for tRNAGlu, which is encoded by an intronless gene. Similar results were also obtained for tRNALeu and tRNAGly (data not shown). The frequency of cells accumulating tRNA inside the nucleus was between 25% and 50%. These results suggest that an active Ran-cycle is required for transport of all tRNA species into the cytoplasm and is in agreement with previous reports (Izaurralde et al. 1997; Kutay et al. 1998; Sarkar and Hopper 1998). However, it cannot be excluded that the nuclear tRNA export defect seen in the rna1-1 strain may partly be a secondary effect, for example, due to inhibition of nuclear import of proteins required for tRNA processing, aminoacylation, or transport (see also below).

We then analyzed cells lacking Los1p. To look at tRNAs that are encoded by intronless genes, we localized tRNAGlu and tRNAGly. In neither case could we detect a strong signal inside the nuclei of the los1− cells when they were grown at 30°C (Fig. 2a) and at lower (23°C) or elevated (37°C) temperatures (data not shown). This suggests that the nuclear export of these two tRNA species is not affected by the disruption of the LOS1 gene. It has been published previously that another intronless tRNA, the major tRNAIle isoacceptor, does display intranuclear accumulation in the los1− strain (Sarkar and Hopper 1998). This accumulation was modest and only observed at an elevated temperature (37°C). Thus, it is possible that the nuclear export of different tRNA species is affected to different extents by the absence of Los1p. Using probes against tRNALeu and the minor tRNAIle, two tRNAs that are encoded by intron containing genes, we detected a significant number of los1− cells (24% and 23%, respectively) displaying a strong intranuclear signal (Fig. 2b). In the case of tRNALeu, we used three different but overlapping probes (Probes I–III), all of which gave very similar results (Fig. 2b,c). It has been shown previously that cells lacking Los1p accumulate unspliced tRNA precursors inside their nuclei, the extent of the accumulation being dependent on the growth temperature (Hurt et al. 1987; Sharma et al. 1996; Sarkar and Hopper 1998). This accumulation might explain the intranuclear signal we observed. However, our mature probes hybridize to the anticodon loop of the tRNAs, whose sequence would be split by the intron in the intron-containing pre-tRNAs (Fig. 2c). Performing Northern analysis under hybridization conditions equally or even less stringent than in the in situ detection on tRNA isolated from wild-type as well as los1− cells, we could confirm that these probes react very well with the mature tRNAs but very poorly with the unspliced pre-tRNAs, which are detected readily by the intron-specific probes (Fig. 2d,e). Therefore, the intranuclear accumulation we observe in los1− cells most likely also reflects a defect in the nuclear export of mature tRNALeu and tRNAIle in addition to the accretion of their corresponding unspliced precursors. This notion is also supported by the fact that in the los1− cells, the probes specific for the introns of tRNALeu and tRNAIle gave considerably weaker intranuclear signals than the corresponding mature probes (Fig. 2f). This was especially evident in the case of tRNALeu and is exactly the opposite of what one would expect if the nuclear tRNAs detected by the mature probes were solely intron-containing precursor forms. Moreover, the extent to which mature tRNAIle accumulated inside the nucleus remained unchanged when the cells were grown at different temperatures (data not shown), whereas accumulation of unspliced pre-tRNAs in los1− cells depends strongly on the growth temperature (Hurt et al. 1987; Sharma et al. 1996).

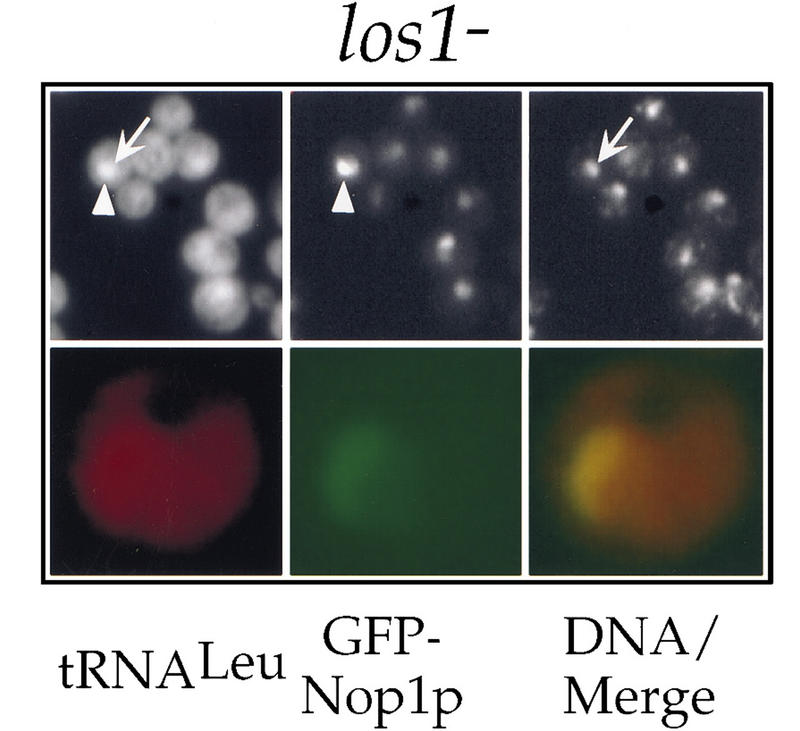

Careful examination of the tRNALeu localization pattern in the los1− cells revealed that the site of intranuclear accumulation did not always coincide with the DNA staining, although it was clearly inside the boundaries of the nuclear envelope as confirmed by colocalization with the nucleoporin Nsp1p (data not shown). This location, adjacent to the DNA signal, might represent the nucleolus. When mature tRNALeu was localized in los1− cells expressing GFP–Nop1p, the site of intranuclear accumulation of tRNALeu partially overlapped with the GFP signal (Fig. 3). This shows that upon inhibition of nuclear export of tRNA, tRNAs accumulate also in the nucleolus and suggests an involvement of nucleolar components in tRNA transport (see also below).

Figure 3.

Accumulation of spliced tRNAs in the nucleolus of los1− cells. (Top) Colocalization of tRNALeu(CAA) with GFP–Nop1p in los1− cells grown at 30°C using the mature probe I. A representative cell is labeled by an arrow that points to the nucleoplasmic space as judged by DAPI staining; the arrowhead points to a nucleolus as judged by the GFP–Nop1p signal. (Bottom) A single cell was color coded to allow a merge of the signals for tRNA (red) and Nop1 (green).

eEF-1A is linked genetically to LOS1

The fact that the los1− mutant has no apparent growth defect and is only affected in the nuclear export of a subset of tRNAs suggests that additional components are required for efficient transport of tRNA from the nucleus into the cytoplasm. To identify such components, we set up a high-copy suppressor screen exploiting the fact that LOS1 becomes essential for viability upon mutation of Arc1p, a nonessential aminoacylation cofactor (Simos et al. 1998). We constructed a los1− arc1− double disruption strain, which could grow only in presence of galactose as it carried a plasmid with the LOS1 gene under the control of the regulatable GAL10 promoter (pGAL–LOS1; strain Y1112). This strain was transformed with a high-copy yeast genomic library and plated on glucose-containing medium. These conditions would allow survival only of those cells that had acquired a library plasmid containing ARC1, LOS1, or an extragenic suppressor. Fast-growing colonies were obtained that harbored library plasmids with either the LOS1 or ARC1 genes. Moreover, three slower-growing colonies contained library plasmids with the TEF1 gene. TEF1 codes for the protein-translation elongation factor eEF-1A (for review, see Negrutskii and El'skaya 1998). This protein is expressed from two genes in the yeast genome, TEF1 and TEF2 that contain identical ORFs. Yeast cells that lack either TEF1 or TEF2 can still grow, but disruption of both genes causes lethality (Cottrelle et al. 1985). eEF-1A is the eukaryotic homolog of EF-Tu and binds in a GTP-dependent manner to aminoacyl tRNAs to deliver them to the A site of elongating ribosomes.

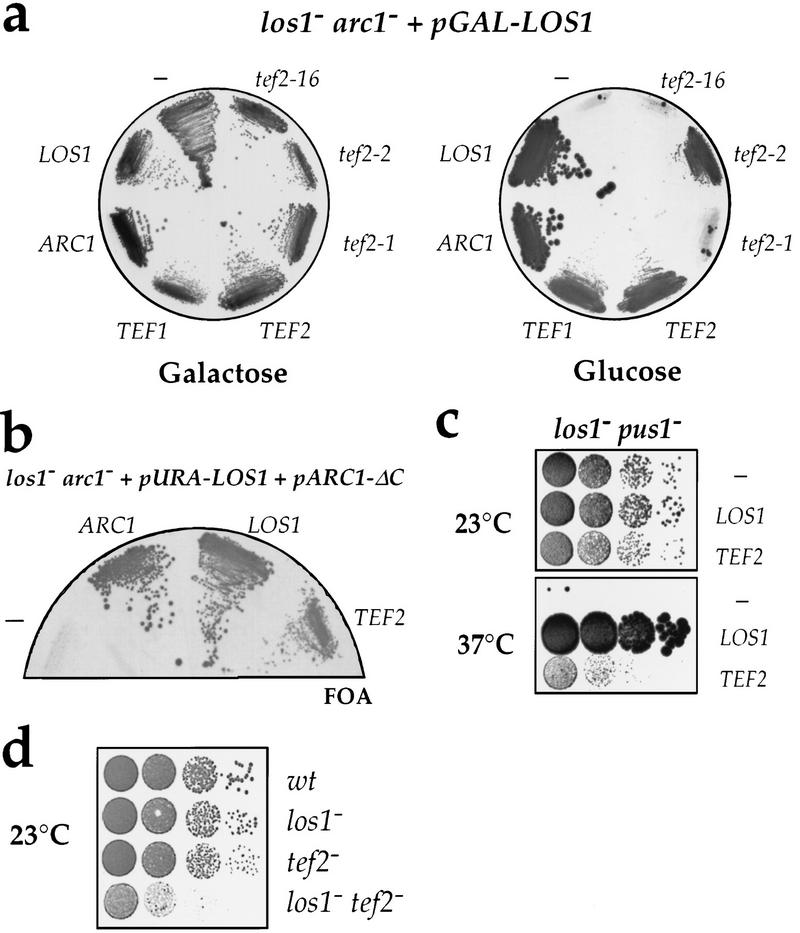

We showed that overexpression of eEF-1A specifically suppresses the disruption of LOS1 by several criteria. First, not only TEF1, but also TEF2, the second gene coding for eEF-1A, and the weak mutant allele tef2-2 allowed growth of the los1− arc1− strain upon depletion of plasmid-encoded Los1p (Fig. 4a). In contrast, two strong mutant alleles of TEF2, tef2-1 or tef2-16 (Sandbaken and Culbertson 1988; Dinman and Kinzy 1997), could not rescue this strain (Fig. 4a). Second, overproduction of eEF-1A restored growth of the synthetically lethal los1− arc1ΔC strain (Fig. 4b). This shows that eEF-1A can act also as a null suppressor of los1. eEF-1A is unlikely to act as a suppressor of the deletion of the carboxy-terminal domain of Arc1p (arc1ΔC), which is lethal when combined with the los1 disruption (Simos et al. 1998), because increased levels of eEF-1A did not affect the slow growth phenotype of the arc1− strain (data not shown). Third, overexpression of TEF1 or TEF2 allowed growth of the temperature-sensitive los1− pus1− strain (Simos et al. 1996b) at the restrictive temperature of 37°C (Fig. 4c). This was specific, because other temperature-sensitive mutants such as mex67-5 (Segref et al. 1997), mtr10-7 (Senger et al. 1998), or xpo1-1 (Stade et al. 1997), which are defective in different nucleocytoplasmic transport pathways, were not suppressed by TEF1 or TEF2 (data not shown). Thus, the absence of Los1p can be compensated specifically by high gene-dosage of eEF-1A. Finally, another genetic interaction between LOS1 and TEF2 was shown independently: whereas neither los1− nor tef2− cells were significantly impaired in growth, combined disruption of both genes led to a synergistic growth defect that was best seen at 23°C (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

eEF-1A is genetically linked to LOS1. (a) The screening strain los1− arc1− plus pGAL–LOS1 (Y1112) transformed with plasmids carrying the indicated genes or mutant alleles was grown on galactose (left) or glucose (right) -containing plates. All genes are on low-copy-number plasmids except TEF1, which is on a high-copy plasmid. (−) Empty plasmid. (b) The double disrupted los1− arc1− strain supplemented with the plasmids pURA–LOS1 and pARC1–ΔC was transformed with the indicated genes on plasmids. To force loss of the pURA–LOS1 plasmid, transformants were subsequently incubated on an FOA-containing plate, on which only ura− cells can grow. (c) The temperature-sensitive double-disrupted los1− pus1− strain was transformed with plasmids carrying the indicated genes and serial dilutions (1:10 steps) of the transformants were spotted on YPD plates and allowed to grow for 2 days at 23°C for 5 days at 37°C. (d) Serial dilutions (1:10 steps) of the indicated strains were spotted on YPD plates and incubated for 2 days at 23°C. (wt) Wild-type parental RS453 strain.

There are two possible explanations for the observed genetic interactions. First, increased levels of eEF-1A may allow more efficient use of the cytoplasmic pool of tRNA, thereby compensating for the decreased export rate of tRNA in the absence of Los1p. Second, eEF-1A may facilitate nuclear tRNA export as a component of a Los1p-independent nuclear export pathway. To discriminate between these two possibilities, we examined the subcellular distribution of tRNA in eEF-1A mutants.

Decreased levels of EF-1A lead to a general nuclear tRNA export defect

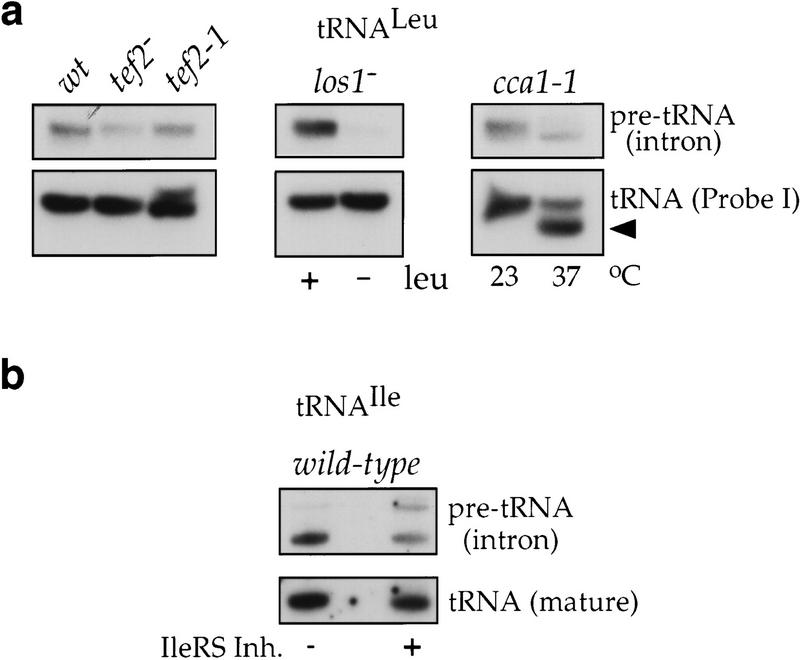

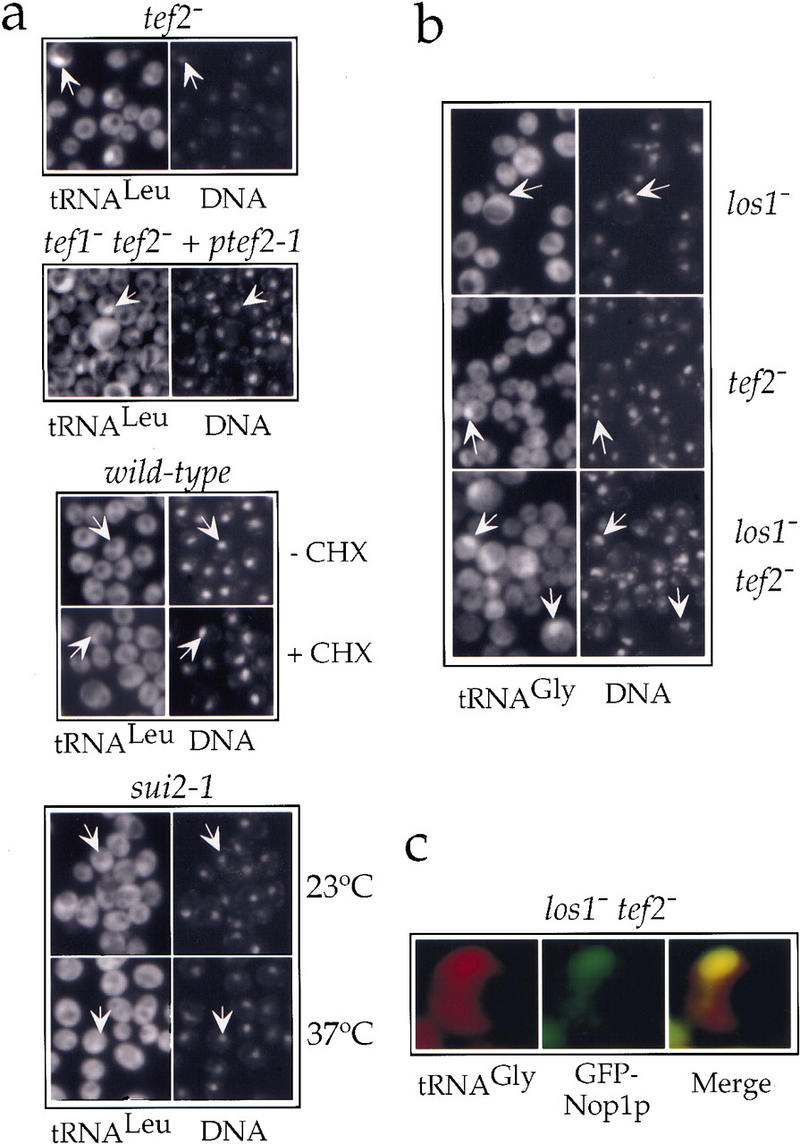

First, we disrupted TEF2, one of the two genes that code for eEF-1A. The cells carrying a single TEF gene have reduced amounts of eEF-1A (Song et al. 1989) but grow almost as well as wild-type cells (Fig. 4d). Nevertheless, this single disruption was sufficient to confer a nuclear tRNA export defect as mature tRNALeu, detected by probe I, accumulated inside the nucleus in ∼8% of the cells (Fig. 5a, top). In contrast to los1− cells, the nuclear export defect in tef2− cells was also evident for tRNAs encoded by intronless genes such as tRNAGly (seen in ∼6% of the cells; Fig. 5b, middle). This frequency of nuclear accumulation (6%–8%) is low but statistically significant, as no accumulating cells were observed in the corresponding isogenic wild-type TEF2 strain (shown in Fig. 1a). Second, we analyzed a double disrupted tef1− tef2− strain complemented by a plasmid-borne mutant allele tef2-1, which displayed a stronger growth retardation than the single disrupted tef2− strain at all temperatures (data not shown). The nuclear accumulation of tRNALeu in this strain was clearly more pronounced, with a frequency similar to that of the los1− strain, that is, in ∼23% of the cells (Fig. 5a). In contrast, the frequency of nuclear accumulation in the isogenic tef1− tef2− strain complemented by the wild-type TEF2 gene on a plasmid was only 4% (data not shown). To make sure that the intranuclear signal of tRNALeu in the tef2− and tef2-1 strains was not due to an accumulation of unspliced precursors, we analyzed tRNA isolated from these strains by Northern blots. Using a probe against the intron of tRNALeu we could not detect any increase in the amount of the unspliced precursors compared with the wild-type strain (Fig. 7, below). Hence, the intranuclear accumulation of tRNALeu reflects an export defect of the mature tRNA and not a defect in splicing. To test whether any block in translation elongation can cause a defect in nuclear tRNA export, we localized tRNALeu and tRNAGlu in cells that had been treated for 30 or 60 min with cycloheximide. Under these conditions, we did not observe any intranuclear accumulation of mature tRNAs (Fig. 5a; data not shown). We finally checked mutants impaired in the initiation of protein translation. No intranuclear accumulation of tRNALeu could be detected in the thermosensitive sui2-1 mutant strain, in which the translation initiation factor eIF2α is mutated, when shifted to the restrictive temperature of 37°C (Fig. 5a). We neither observed a nuclear tRNA export defect in the thermosensitive gcd1-501 mutant allele of initiation factor eIF2Bγ or the slow-growing gcd11-G397A and gcd11-R510H mutant alleles of eIF2γ (data not shown), despite the fact that the latter two alleles were shown previously to be synthetically lethal to the LOS1 disruption (Hellmuth et al. 1998). Taken together, these results show that normal expression levels of eEF-1A are required for efficient nuclear export of tRNA and suggest that eEF-1A can suppress the LOS1 gene disruption by facilitating exit of tRNA from the nucleus.

Figure 5.

eEF-1A is required for efficient nuclear tRNA export. (a) Localization of tRNALeu(CAA) (probe I) in single disrupted tef2− cells grown at 30°C (first panel from top); in double disrupted tef1− tef2− cells complemented by a plasmid carrying the tef2-1 allele grown at 23°C (second panel); in cells incubated for 60 min in the absence (−CHX) or presence (+CHX) of 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (third panel); in the thermosensitive mutant sui2-1 grown at 23°C or shifted to 37°C for 4 hr as indicated (bottom). (b) Localization of tRNAGly(GCC) in the los1− or tef2− single disruption mutants or the los1− tef2− double disruption mutant. (c) Colocalization of tRNAGly(GCC) and Nop1p in the los1− tef2− double disruption mutant. Color codes are as in Fig. 1. Representative cells are labeled by arrows that point to the nucleoplasmic space as defined by DAPI staining.

Figure 7.

Unspliced tRNA precursors do not accumulate upon inhibition of nuclear tRNA export. (a) Equal amounts of total RNA extracted from the indicated strains were analyzed by Northern with probes for mature (probe I) or intron containing tRNALeu(CAA). (wt) Wild type grown at 30°C; (tef2−) tef2− grown at 30°C; (tef2-1) tef1− tef2-1 grown at 23°C; (los1) los1− cells grown in the presence (+) or absence (−) of leucine at 30°C; (cca1-1) cca1-1 cells grown at 23°C or shifted to 37°C for 4 hr. The arrowhead indicates tRNA lacking the three terminal CCA nucleotides due to the inactivation of Cca1p. (b) Total RNA was extracted from wild-type cells incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitor and analyzed by Northern with probes for mature or intron-containing tRNAIle(UAU).

We then examined whether the synthetic slow growth phenotype observed in the los1− tef2− double disruption mutant (Fig. 4d) could be due to an enhanced defect in nuclear tRNA export. Although the export of the intronless tRNAGly was not, or only weakly affected in the los1− and tef2− single mutants, respectively, the los1− tef2− double disruption mutant cells displayed a stronger defect, the frequency of intranuclear accumulation rising from 6% (in tef2−) to 16% (Fig. 5b, cf. bottom with the middle and top panels). Introducing a plasmid-borne LOS1 into this strain brought the frequency of accumulation down to ∼1%, suggesting that a slight overexpression of Los1p may compensate for the tRNA export defect caused by the reduction in the levels of eEF-1A (data not shown). This finding and the synergistic defect observed upon impairing both Los1p and eEF-1A functions, suggests a certain extent of redundancy between the export routes that involve these two components. Finally, as was the case for the los1− mutant, the site of intranuclear accumulation of tRNA in the los1− tef2− strain coincided largely with the nucleolar signal of GFP–Nop1p (Fig. 5c).

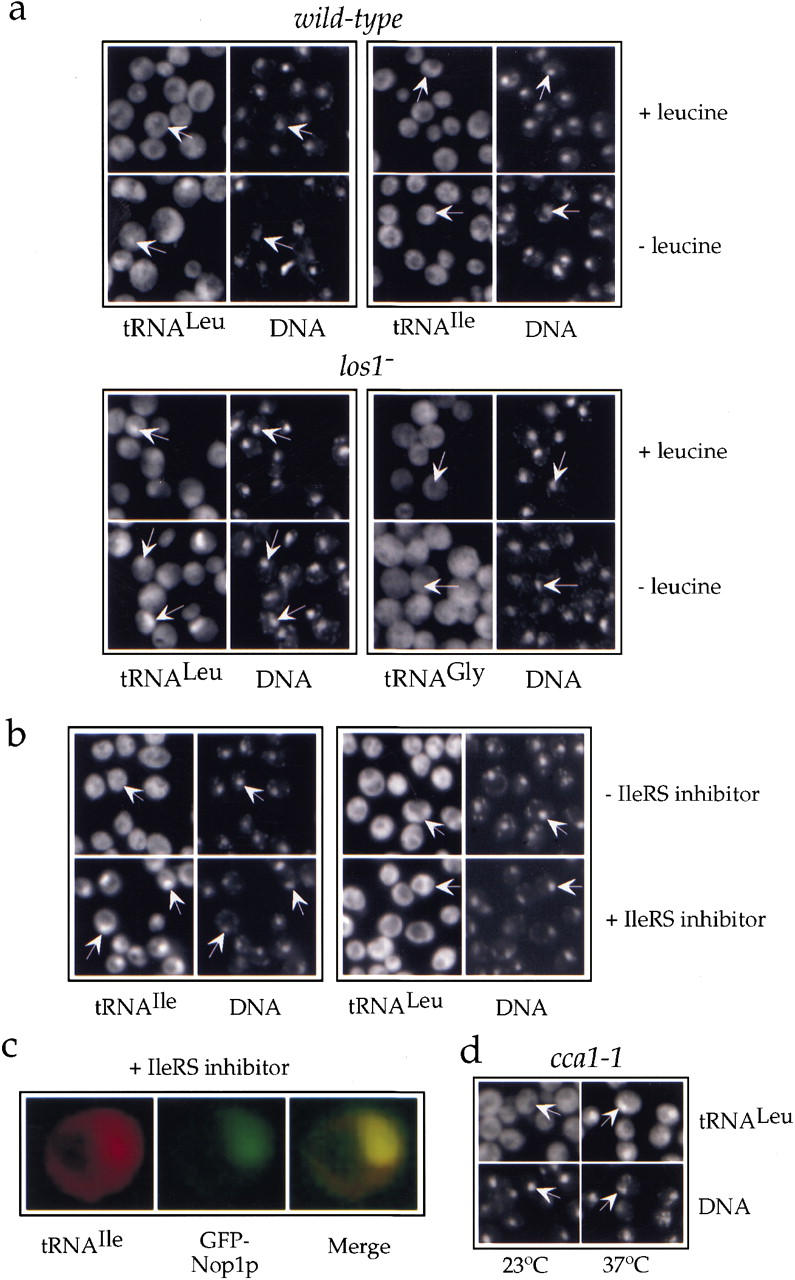

Aminoacylation is required for nuclear export of tRNA

eEF-1A can only bind efficiently to aminoacylated tRNAs (Dreher et al. 1999), indicating that aminoacylation of tRNA may also be a prerequisite for nuclear tRNA export. Aminoacylation has been shown previously to be important for nuclear export of tRNA in the Xenopus system (Lund and Dahlberg 1998). To examine the role of aminoacylation in nuclear tRNA export in yeast, we localized certain tRNA species after their aminoacylation had been specifically inhibited. Because starvation for a particular amino acid reduces the aminoacylation levels of the cognate tRNA (Clare and Oliver 1982), we first localized tRNALeu in our yeast wild-type strain RS453, which is auxotrophic for leucine, after transfer to minimal medium lacking this amino acid. Under these conditions, we observed with a low frequency (7%), intranuclear accumulation of mature tRNALeu (Fig. 6a, top left). As a control, we looked at the localization of tRNAIle under the same conditions. A nuclear signal for tRNAIle could also be detected in some cells (Fig. 6a, top right). However, this signal was clearly weaker than the corresponding one for tRNALeu, suggesting that leucine starvation preferentially affected the nuclear export of tRNALeu. When we performed the same experiment using the los1− strain (which is also a leucine auxotrophic strain derived from RS453), starvation for leucine led to a strong and very frequent (90%) nuclear accumulation of tRNALeu, whereas localization of tRNAGly, which was used as control, was little affected (Fig. 6a, bottom). Additionally, starvation for adenine did not cause any further nuclear accumulation of tRNA (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of tRNA aminoacylation blocks nuclear tRNA export. (a) Localization of tRNALeu(CAA) (probe I) or tRNAIle(UAU) in the leucine auxotrophic wild-type strain RS453 (top) and tRNALeu(CAA) or tRNAGly(GCC) in the isogenic los1− disruption mutant (bottom) grown in complete synthetic medium (+leucine) or shifted for 3 hr to medium lacking leucine (−leucine). (b) Localization of tRNAIle(UAU) and tRNALeu(CAA) in the wild-type strain RS453 grown for 2 hr in complete synthetic medium in the absence (−) or the presence (+) of 500 μg/ml of the isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitor BAY10-8888. (c) Colocalization of tRNAIle(UAU) and GFP–Nop1p in RS453 cells grown for 2 hr in the presence of 50 μg/ml BAY10-8888. Color codes are as in Fig. 1. (d) Localization of tRNALeu(CAA) (probe I) in the thermosensitive mutant cca1-1 grown at 23°C or shifted to 37°C for 4 hr. Representative cells are labeled by arrows that point to the nucleoplasmic space as defined by DAPI staining.

To block aminoacylation of another tRNA species, we used the cyclic β-amino acid BAY10-8888, which has been shown previously to specifically inhibit the yeast isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (Ziegelbauer et al. 1998). Addition of this inhibitor to the culture medium of the RS453 strain caused a fast block of the nuclear export of tRNAIle in almost all of the cells (Fig. 6b). This effect was specific as nuclear export of tRNALeu was hardly affected (Fig. 6b). Colocalization experiments confirmed also in this case that mature tRNAs that cannot be exported from the nucleus accumulate to a certain extent in the nucleolus (Fig. 6c). This shows that nucleolar accumulation of mature tRNAs is a consequence of inhibiting nuclear tRNA export.

Finally, we tested tRNA export in the yeast mutant cca1-1, which is expected to display a more general tRNA-aminoacylation defect. The cca1-1 mutant strain carries a temperature-sensitive mutation in the CCA1 gene that codes for the essential tRNA-nucleotidyl transferase (Cca1p), the enzyme that completes the maturation of the 3′ ends of all tRNAs by adding the three terminal CCA bases (Aebi et al. 1990). CCA addition is essential for aminoacylation. Incubation of the cca1-1 strain at nonpermissive temperatures caused accumulation of tRNAs inside the nuclei of almost all cells (Fig. 6d). This nuclear export defect was of similar intensity for all tRNAs tested (data not shown). Thus, tRNAs lacking the 3′ terminal CCA cannot exit the nucleus, most likely because they cannot be aminoacylated. As the CCA tail is required for recognition of tRNAs by the mammalian homolog of Los1p, Xpo-t (Arts et al. 1998b; Lipowsky et al. 1999), tRNAs without it may not be able to access the Los1p-dependent alternative export pathway either.

Northern blot analysis revealed that incubation of the cca1-1 strain at the nonpermissive temperature caused a shortening of the tRNA molecules due to the lack of the three 3′ terminal nucleotides (Fig. 7a). The same analysis also showed that none of the conditions that inhibited aminoacylation (leucine starvation, treatment with the isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitor, or the cca1-1 mutation) nor the mutations in tef2 that caused an intranuclear localization of tRNA, resulted in an accumulation of unspliced tRNA precursors (Fig. 7), confirming that in all cases the observed nuclear signal is due to mature (spliced) tRNAs that are unable to leave the nucleus. Furthermore, this result suggests that inhibition of nuclear tRNA export is not the cause of the splicing defect observed the los1− strain. As shown in Figure 7a, when the los1− cells are analyzed under leucine starvation conditions that cause a strong nuclear export defect for tRNALeu, the amount of unspliced pre-tRNALeu is not higher than under normal growth conditions. As a matter of fact, it is even decreased, probably because the flow of newly synthesized tRNA to the splicing machinery gets reduced as the cells respond to starvation by turning down tRNA transcription.

Discussion

Using a genetic screen to find suppressors of a los1 synthetic-lethal mutant, we identified TEF1, the gene coding for the protein translation elongation factor eEF-1A. A requirement of eEF-1A for nuclear export of tRNA was subsequently shown by use of a tRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization assay. Unlike the los1− strain, in which the export of the intronless tRNAs we tested was very little affected, strains with reduced amounts of, or mutated, eEF-1A exhibited accumulation of mature tRNAs encoded by both intronless and intron-containing genes; this defect was aggravated in the absence of Los1p. Inhibition of tRNA aminoacylation by amino acid starvation, a specific aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitor or impaired CCA addition at the 3′ end of tRNAs also led to a strong nuclear tRNA export defect. Finally, colocalization of non-exported mature tRNAs with GFP–Nop1p showed a preferential nucleolar accumulation of these tRNAs.

While this manuscript was under revision, a report was published showing that temperature-sensitive aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase mutants also exhibit a nuclear tRNA export defect when incubated at nonpermissive conditions (Sarkar et al. 1999). A mutation in the methionyl-tRNA synthetase affected the export of the cognate tRNA, whereas mutations in the isoleucyl- or tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases affected the export of both cognate and non-cognate tRNAs. On the one hand, these data are in agreement with our results on the requirement for aminoacylation for nuclear tRNA export. On the other hand, we have shown that inhibition of the leucyl- and isoleucyl-tRNA synthetases affected predominantly the export of the corresponding cognate tRNAs. A possible explanation for the difference in the case of isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase is that the enzyme activity is affected to a different extent by the applied methods (a temperature-sensitive mutation vs. competitive inhibition by a substrate analog).

According to both our and the recently published data (Sarkar et al. 1999), two nuclear tRNA export pathways may operate in yeast. One would involve the exportin Los1p, whereas the other would depend on aminoacylation and require eEF-1A. Because the nuclear tRNA export defect becomes stronger if both pathways are simultaneously inhibited (see Figs. 5b and 6a), they appear to be partly redundant. Thus, if one of the two pathways is impaired, tRNAs gain access to the other. This redundancy could also explain why the nuclear tRNA export defect in the los1− strain is not observed in all of the cells and for all tRNAs but rather in a subpopulation of cells and for a subset of tRNA species. When aminoacylation is also inhibited in the los1− strain, almost all cells display intranuclear accumulation of mature, spliced tRNALeu as shown in Figure 6a. In addition, the Los1p-dependent pathway appears to be less important for tRNAs encoded by intronless genes, reflecting a possible coupling of tRNA splicing to the Los1p pathway. This is in agreement with the fact that tRNA splicing is also impaired in los1 mutants, causing accumulation of intron-containing tRNA precursors (Hurt et al. 1987; Sarkar and Hopper 1998). In contrast, no accumulation of intron-containing pre-tRNAs could be detected upon inhibition of nuclear tRNA export by reducing tRNA aminoacylation levels in agreement with previous results from the Xenopus system (Lund and Dahlberg 1998).

In another model that could explain our observations, the aminoacylation-dependent pathway is the default route in yeast, followed by all tRNAs that leave the nucleus, whereas Los1p offers an additional auxiliary but not essential function, the importance of which may vary for the different tRNA species. In this case, tRNA aminoacylation and eEF-1A may also be required for the Los1p-mediated nuclear tRNA export. It has been shown previously that the disruption of LOS1 is synthetically lethal with mutations in the translation initiation factor eIF-2γ (Gcd11p), which binds to the charged initiator tRNAMet and delivers it to the small ribosomal subunit (Hellmuth et al. 1998). Moreover, Los1p interacts with eIF-2γ in the two-hybrid system. Therefore, Los1p itself may be able to access directly the protein translation machinery. However, unlike for eEF-1A, we were unable to detect intranuclear accumulation of initiator tRNAMet or other tRNAs in eIF-2γ mutants (H. Grosshans, E. Hurt, and G. Simos, unpubl.). The requirement for aminoacylation for efficient tRNA nuclear export also explains the genetic interaction between Los1p and the carboxy-terminal domain of Arc1p, as the latter has been shown to facilitate aminoacylation by delivering tRNA to at least two aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (Simos et al. 1998).

Major translation factors and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, which are both ancestral and abundant tRNA-binding proteins, may actually have been the first components to be recruited for nuclear export of tRNA when the processes of transcription and translation became separated spatially by the nuclear envelope. The subsequent evolution of a sophisticated nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery may then have led to the appearance of an exportin specialized for tRNA such as Los1p. In higher eukaryotic organisms, such as Xenopus laevis, Xpo-t, the homolog of Los1p, may actually have become the major mediator of nuclear tRNA export, with tRNA aminoacylation playing only an auxiliary role (Arts et al. 1998b; Lund and Dahlberg 1998; Lipowsky et al. 1999).

How can tRNA aminoacylation and eEF-1A affect the nuclear export of tRNA? The requirement for aminoacylation suggests that tRNAs can be charged inside the nucleus. This notion is supported by findings from both the Xenopus and the yeast system (Lund and Dahlberg 1998; Sarkar et al. 1999). Moreover, putative nuclear localization sequences (NLS) have recently been identified by sequence analysis in many yeast aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (Schimmel and Wang 1999). Intranuclear aminoacylation of tRNA may not only serve as a final proof-reading step (Lund and Dahlberg 1998) but also release mature tRNAs from processing sites thereby relieving nuclear retention. In the next step, the aminoacylated tRNAs would have to both leave the nucleus and bind to eEF-1A. Although eEF-1A is predominantly located in the cytoplasm, it has also been detected inside the nuclei of various cell systems (Barbarese et al. 1995; Billaut-Mulot et al. 1996; Sanders et al. 1996; Gangwani et al. 1998). Intranuclear eEF-1A may then facilitate the transport of tRNAs through the nuclear pore complexes. However, using an epitope-tagged form of yeast eEF-1A (which is functional as it can complement the tef1− tef2− double disruption), we could only detect it in the cytoplasm, concentrated around the nuclear periphery both in wild-type cells and in the xpo1-1 mutant strain which is defective in nuclear protein export (H. Grosshans, E. Hurt, and G. Simos, unpubl.). Although a small nuclear pool of eEF-1A may have escaped detection, this observation might mean that eEF-1A actually does not have to enter the yeast nucleus. Instead, it may function at the cytoplasmic face of the nuclear pore complexes facilitating the release of charged tRNAs from aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. In fact, eEF-1A has been shown to interact directly with aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and to stimulate their activity by promoting dissociation of the charged tRNA (Reed et al. 1994; Negrutskii et al. 1996, 1999). Our findings would thus support an extended tRNA channeling model according to which tRNAs are directly transferred between components of the tRNA biogenesis and protein translation machineries (Stapulionis and Deutscher 1995; Negrutskii and El'skaya 1998; Wolin and Matera 1999). Concerning the involvement of the aminoacylation cofactor Arc1p, this protein has been localized previously, predominantly in the cytoplasm and in close association with the nuclear periphery (Simos et al. 1996a). However, it has been suggested that Arc1p contains a classical NLS (Schimmel and Wang 1999) and a major pool of its mammalian homolog, p43, has been localized by immune-electron microscopy inside the nucleus, which also contained a small portion of some aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (Popenko et al. 1994). Therefore, the presence of a minor pool of Arc1p in the yeast nucleus cannot be excluded, and this protein may facilitate aminoacylation in both the nuclear and the cytoplasmic compartments.

The requirement for aminoacylation and eEF-1A for both nuclear tRNA export and protein translation suggests a coordinated regulation of these two processes. The key element in this coordination appears to be eEF-1A, as mutations in other translation factors or inhibition of protein translation by cycloheximide did not produce a nuclear tRNA export defect (see Fig. 5a). One might expect that interfering with protein translation at any step would cause saturation of eEF-1A with charged tRNAs and therefore also affect tRNA export. However, as reported previously (Condeelis 1995), the amount of eEF-1A in a cell is normally in high-molar excess of the other components of the translation machinery, including tRNA. Therefore, even if the whole pool of cellular tRNA becomes charged because of lack of deacylation upon blocking translation, eEF-1A is unlikely to become saturated. Furthermore, the total concentration of cellular tRNA is not expected to increase beyond a certain level, because a block in translation will soon also cause a halt in tRNA transcription (as transcription and processing factors will be depleted). When the synthesis of new tRNAs has stopped, an intranuclear accumulation will not be detectable even if nuclear export ceases to be functional.

Finally, upon inhibition of nuclear export, tRNAs appear to accumulate predominantly in the nucleolus, the site of rRNA synthesis and processing (see Figs. 3, 5c, and 6c). This might simply reflect an involvement of the nucleolus in tRNA maturation (Bertrand et al. 1998). However, because the transcription and processing machineries of rRNA and tRNA share several components (Lalo et al. 1993; Chamberlain et al. 1998), the presence of tRNA in the nucleolus may also be significant for the regulation of ribosome biogenesis. If tRNA aminoacylation is unable to proceed, tRNAs would accumulate inside the nucleolus, where they may act as a signal for cessation of transcriptional activity by RNA polymerase I, causing onset of the stringent response. This would allow an additional level of communication between the cytoplasm and the nucleus.

Materials and methods

Plasmids and strains

The following published mutant strains were used: cca1-1 (Aebi et al. 1990), sui2-1 (Donahue et al. 1988), gcd1-501 (Harashima and Hinnebusch 1986), gcd11-G397A and gcd11-R510H (Dorris et al. 1995), tef1− tef2− (Sandbaken and Culbertson 1988), los1−, los1− pus1− (Simos et al. 1996b), arc1−, los1− arc1− (Simos et al. 1996a), los1− arc1ΔC (Simos et al. 1998) and rna1-1 (Corbett et al. 1995). For the suppressor screen, a yeast genomic library in the high-copy number vector YEp352–URA3 was used (te Heesen et al. 1993). To disrupt the TEF2 gene in the RS453 strain, the HIS3 gene was introduced at the single NcoI site at nucleotides +618 of the TEF2–ORF. Disruption of the TEF2 gene was confirmed by PCR. Mating of the single disrupted tef2− strain to los1− and subsequent tetrad dissection of the diploid yielded the double disrupted haploid mutant los1− tef2−. The conditional synthetic-lethal (sl) mutant Y1112 was constructed by transforming los1− arc1− plus pURA–LOS1 with pGAL–LOS1 and shuffling out pURA–LOS1 on SCGal plus FOA (5′-fluoro-orotic acid). The resulting strain grew in rich galactose medium (YPGal) but not in glucose (YPD). Depletion of Los1p upon shift to glucose-containing medium was confirmed by Western blotting.

Suppressor screen

The genomic library was screened for suppressors of the conditional sl phenotype of Y1112 by plating transformants on YPD plates. Clones that could not grow on SDC plus FOA, thus confirming plasmid dependence of the suppression, were further analyzed. To exclude complementation instead of suppression, whole cell extracts were examined by Western blot analysis for the presence of Los1p or Arc1p. Recovered plasmids, which upon retransformation into Y1112 conferred growth in glucose, were sequenced.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

The method for localization of tRNA by fluorescence in situ hybridization was adapted from a protocol for poly(A+)–RNA detection (Amberg et al. 1992) with the following changes: The methanol/acetone dehydration step was omitted, tRNA in the hybridization buffer was replaced with the same concentration of Escherichia coli 5S rRNA, and RNasin (Promega) added to a final concentration of 0.4 U/μl. Moreover, fixation of the cells was performed as described in (Sarkar and Hopper 1998). Hybridizations were performed in hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide (for details see Amberg et al. 1992) with 0.4 pmole/μl of the respective Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide probe at 37°C overnight. DNA was stained with 50 ng/ml DAPI, and slides mounted with Mowiol.

Cells were scored as positive for intranuclear accumulation if examination of the tRNA staining pattern allowed unequivocal identification of the nuclear compartment as defined by the DAPI/GFP–Nop1p staining. More than 300 cells from at least two independent experiments were counted for statistical analysis.

Fluorescent probes

Labeled oligonucleotides were purchased from Interactiva. Sequences are for mature tRNALeu (anticodon, CAA), probe I, 5′-GCATCTTACGATACCTGAG/CTTGAA-3′; tRNALeu (CAA), probe II, 5′-CTTACGATACCTGAG/CTTGAATCAGGCGC-3′; tRNALeu (CAA), probe III, 5′-TACGATACCTGAG/CTTGAATCAGGC-3′; minor tRNAIle (UAU), 5′-CCACGACGGTCGCGT/TATAAGCACGAAGCT-3′; tRNAGlu (UUC), 5′-CGGTCTCCACGGTGAAAGC-3′; tRNAGly (GCC), 5′-GGCCCAACGATGGCAACG-3′. Triplets that hybridize to the anticodons are underlined, the position of the splice sites in tRNALeu and tRNAIle, respectively, is indicated by a slash. Sequences for intron-specific probes are for tRNALeu (CAA), 5′-TATTCCCACAGTTAACTGCGGTCAAGATAT-3′, and for tRNAIle (UAU), 5′-GTTTGAAAGGTCTTTGGCACAGAAACTTCG-3′.

The specificity of the probes was checked by Northern analysis using nonfluorescent, radioactively labeled oligos with identical sequences.

Northern blot analysis

Total tRNA was extracted from yeast cells as described (Sharma et al. 1996), separated on a 10% urea-polyacrylamide denaturing gel and transferred to Hybond N+ membranes. Hybridization reactions with radioactively labeled probes were routinely performed at 37°C in 6x SSPE (900 mm NaCl, 60 mm NaH2PO4, 0.3 mm EDTA). In some experiments, 50% formamide was added in the hybridization buffer as indicated in the Figure legends.

Inhibition of tRNA aminoacylation

To reduce the levels of aminoacylation of tRNALeu, exponentially growing, leucine-auxotrophic cells were shifted from complete minimal medium (SDC plus all) to medium without leucine (SDC minus leu) for 3 hr. Aminoacylation of tRNAIle was inhibited by adding BAY10-8888 to 50 μg/ml or 500 μg/ml final concentration to exponentially growing cells in SDC plus all. BAY10-8888 has been demonstrated previously to specifically affect isoleucyl-tRNA-synthetase (Ziegelbauer et al. 1998).

Miscellaneous

Cells were examined using a Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope equipped with a Xillix Microimager CCD camera. Data were processed using the Improvision Openlab software. All experiments were performed on exponentially growing cells. All shifts to 37°C were performed in rich medium (YPD). When required, cycloheximide was added in the culture medium at a concentration of 10 μg/ml.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Jacobson, T.G. Kinzy, E. Hannig, and A.G. Hinnebusch for gifts of strains and K. Stünkel (Bayer AG) for gift of BAY10-8888. E.H. and G.S. are recipients of grants from DFG (SFB352-B11).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL cg2@ix.urz.uni-heidelberg.de; FAX +49 (0)6221-544369.

References

- Adam SA. Transport pathways of macromolecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:402–406. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebi M, Kirchner G, Chen JY, Vijayraghavan U, Jacobson A, Martin NC, Abelson J. Isolation of a temperature-sensitive mutant with an altered tRNA nucleotidyltransferase and cloning of the gene encoding tRNA nucleotidyltransferase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16216–16220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg DC, Goldstein AL, Cole CN. Isolation and characterization of RAT1: An essential gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae required for the efficient nucleocytoplasmic trafficking of mRNA. Genes & Dev. 1992;6:1173–1189. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts GJ, Fornerod M, Mattaj IW. Identification of a nuclear export receptor for tRNA. Curr Biol. 1998a;8:305–314. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts GJ, Kuersten S, Romby P, Ehresmann B, Mattaj IW. The role of exportin-t in selective nuclear export of mature tRNAs. EMBO J. 1998b;17:7430–7441. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarese E, Koppel DE, Deutscher MP, Smith CL, Ainger K, Morgan F, Carson JH. Protein translation components are colocalized in granules in oligodendrocytes. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2781–2790. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.8.2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand E, Houser-Scott F, Kendall A, Singer RH, Engelke DR. Nucleolar localization of early tRNA processing. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:2463–2468. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billaut-Mulot O, Fernandez-Gomez R, Loyens M, Ouaissi A. Trypanosoma cruzi elongation factor 1-alpha: Nuclear localization in parasites undergoing apoptosis. Gene. 1996;174:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain JR, Lee Y, Lane WS, Engelke DR. Purification and characterization of the nuclear RNase P holoenzyme complex reveals extensive subunit overlap with RNase MRP. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1678–1690. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare JJ, Oliver SG. The regulation of RNA synthesis in yeast. V. tRNA charging studies. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;188:96–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00333000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condeelis J. Elongation factor 1 alpha, translation and the cytoskeleton. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:169–170. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88998-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett AH, Koepp DM, Schlenstedt G, Lee MS, Hopper AK, Silver PA. Rna1p, a Ran/TC4 GTPase activating protein, is required for nuclear import. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:1017–1026. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.5.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrelle P, Cool M, Thuriaux P, Price VL, Thiele D, Buhler JM, Fromageot P. Either one of the two yeast EF-1 alpha genes is required for cell viability. Curr Genet. 1985;9:693–697. doi: 10.1007/BF00449823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinman JD, Kinzy TG. Translational misreading: Mutations in translation elongation factor 1alpha differentially affect programmed ribosomal frameshifting and drug sensitivity. RNA. 1997;3:870–881. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue TF, Cigan AM, Pabich EK, Valavicius BC. Mutations at a Zn(II) finger motif in the yeast eIF-2 beta gene alter ribosomal start-site selection during the scanning process. Cell. 1988;54:621–632. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorris DR, Erickson FL, Hannig EM. Mutations in GCD11, the structural gene for eIF-2 gamma in yeast, alter translational regulation of GCN4 and the selection of the start site for protein synthesis. EMBO J. 1995;14:2239–2249. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher TW, Uhlenbeck OC, Browning KS. Quantitative assessment of EF-1alpha.GTP binding to aminoacyl-tRNAs, aminoacyl-viral RNA, and tRNA shows close correspondence to the RNA binding properties of EF-Tu. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:666–672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwani L, Mikrut M, Galcheva-Gargova Z, Davis RJ. Interaction of ZPR1 with translation elongation factor-1alpha in proliferating cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1471–1484. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans, H., G. Simos, and E. Hurt. 2000. Transport of tRNA out of the nucleus-direct channeling to the ribosome? J. Struct. Biol. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Harashima S, Hinnebusch AG. Multiple GCD genes required for repression of GCN4, a transcriptional activator of amino acid biosynthetic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3990–3998. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth K, Lau DM, Bischoff FR, Künzler M, Hurt EC, Simos G. Yeast Los1p has properties of an exportin-like nucleocytoplasmic transport factor for tRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6374–6386. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt DJ, Wang SS, Yu-Huei L, Hopper AK. Cloning and characterization of LOS1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene that affects tRNA splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1208–1216. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.3.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaurralde E, Kutay U, von Kobbe C, Mattaj IW, Görlich D. The asymmetric distribution of the constituents of the Ran system is essential for transport into and out of the nucleus. EMBO J. 1997;16:6535–6547. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutay U, Lipowsky G, Izaurralde E, Bischoff FR, Schwarzmaier P, Hartmann E, Görlich D. Identification of a tRNA-specific nuclear export receptor. Mol Cell. 1998;1:359–369. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalo D, Carles C, Sentenac A, Thuriaux P. Interactions between three common subunits of yeast RNA polymerases I and III. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:5524–5528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipowsky G, Bischoff FR, Izaurralde E, Kutay U, Schäfer S, Gross HJ, Beier H, Görlich D. Coordination of tRNA nuclear export with processing of tRNA. RNA. 1999;5:539–549. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299982134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E, Dahlberg JE. Proofreading and aminoacylation of tRNAs before export from the nucleus. Science. 1998;282:2082–2085. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrutskii BS, El'skaya AV. Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha: Structure, expression, functions, and possible role in aminoacyl-tRNA channeling. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1998;60:47–78. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60889-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrutskii BS, Budkevich TV, Shalak VF, Turkovskaya GV, El'skaya AV. Rabbit translation elongation factor 1α stimulates the activity of homologous aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:18–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negrutskii BS, Shalak VF, Kerjan P, El'skaya AV, Mirande M. Functional interaction of mammalian valyl-tRNA synthetase with elongation factor EF-1α in the complex with EF-1H. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4545–4550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popenko VI, Ivanova JL, Cherny NE, Filonenk VV, Beresten SF, Wolfson AD, Kisselev LL. Compartmentalization of certain components of the protein synthesis apparatus in mammalian cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1994;65:60–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed VS, Wastney ME, Yang DCH. Mechanisms of the transfer of aminoacyl-tRNA from aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase to the elongation factor 1 alpha. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32932–32936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandbaken MG, Culbertson MR. Mutations in elongation factor EF-1 alpha affect the frequency of frameshifting and amino acid misincorporation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1988;120:923–934. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.4.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders J, Brandsma M, Janssen GM, Dijk J, Moller W. Immunofluorescence studies of human fibroblasts demonstrate the presence of the complex of elongation factor-1 beta gamma delta in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1113–1117. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.5.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Hopper AK. tRNA nuclear export in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: In situ hybridization analysis. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3041–3055. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.11.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Azad AK, Hopper AK. Nuclear tRNA aminoacylation and its role in nuclear export of endogenous tRNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:14366–14371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel P, Wang CC. Getting tRNA synthetases into the nucleus. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:127–128. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01369-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segref A, Sharma K, Doye V, Hellwig A, Huber J, Hurt EC. Mex67p which is an essential factor for nuclear mRNA export binds to both poly(A)+ RNA and nuclear pores. EMBO J. 1997;16:3256–3271. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger B, Simos G, Bischoff FR, Podtelejnikov AV, Mann M, Hurt EC. Mtr10p functions as a nuclear import receptor for the mRNA binding protein Npl3p. EMBO J. 1998;17:2196–2207. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K, Fabre E, Tekotte H, Hurt EC, Tollervey D. Yeast nucleoporin mutants are defective in pre-tRNA splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:294–301. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.1.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simos G. Nuclear export of tRNA. Protoplasma. 1999;209:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Simos G, Hurt E. Transfer RNA biogenesis: A visa to leave the nucleus. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R238–R241. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simos G, Segref A, Fasiolo F, Hellmuth K, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Hurt EC. The yeast protein Arc1p binds to tRNA and functions as a cofactor for methionyl- and glutamyl-tRNA synthetases. EMBO J. 1996a;15:5437–5448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simos G, Tekotte H, Grosjean H, Segref A, Sharma K, Tollervey D, Hurt EC. Nuclear pore proteins are involved in the biogenesis of functional tRNA. EMBO J. 1996b;15:2270–2284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simos G, Sauer A, Fasiolo F, Hurt EC. A conserved domain within Arc1p delivers tRNA to aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Mol Cell. 1998;1:235–242. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JM, Picologlou S, Grant CM, Firoozan M, Tuite MF, Liebman S. Elongation factor EF-1 alpha gene dosage alters translational fidelity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4571–4575. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.10.4571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stade K, Ford CS, Guthrie C, Weis K. Exportin 1 (Crm1p) is an essential nuclear export factor. Cell. 1997;90:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80370-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapulionis R, Deutscher MP. A channeled tRNA cycle during mammalian protein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:7158–7161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- te Heesen S, Knauer R, Lehle L, Aebi M. Yeast Wbp1p and Swp1p form a protein complex essential for oligosaccharyl transferase activity. EMBO J. 1993;12:279–284. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobian JA, Drinkard L, Zasloff M. tRNA nuclear transport: Defining the criticial region of human tRNAMet by point mutagenesis. Cell. 1985;43:415–422. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin SL, Matera AG. The trials and travels of tRNA. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:1–10. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegelbauer K, Babczinski P, Schönfeld W. Molecular mode of action of the antifungal beta-amino acid BAY 10-8888. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2197–2205. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]