Abstract

The development of a simple, efficient, scalable, and stereocontrolled synthesis of a common intermediate en route to the axinellamines, massadines, and palau’amine is reported. This completely new route was utilized to prepare the axinellamines on a gram scale. In a more general sense, three distinct and enabling methodological advances were made during these studies: 1. ethylene glycol-assisted Pauson-Khand cycloaddition reaction, 2. a Zn/In-mediated Barbier type reaction, and 3. a TfNH2-assisted chlorination-spirocyclization.

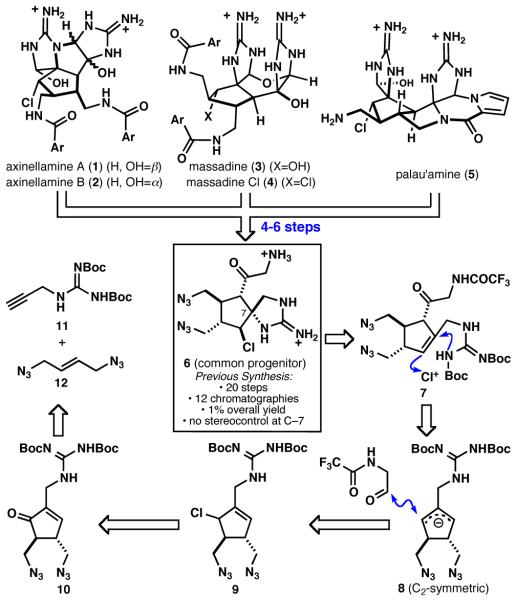

The axinellamines (1-2), massadines (3-4), and palau’amine (5) reside at the upper limit of structural complexity within the bioactive pyrrole imidazole marine alkaloid (PIA) family (Figure 1).1 As such, extensive effort has been expended towards their total chemical synthesis.2 Although the feasibility of generating 1–5 in a laboratory setting on a milligram scale was demonstrated over the past three years,2a,3 the ultimate challenge of procuring large quantities of these alkaloids, a prerequisite for any serious biological follow-up, has yet to be met. The center of inefficiency in the Scripps route to 1–52a,3 lies in the preparation of common progenitor spirocycle 6 which is synthesized by a lengthy 20-step sequence in 1% overall yield (40% ideality4) that proceeds without stereocontrol at C–7 (ca. 1:1 ratio formed). Only four to six additional steps are required to controllably convert 6 into 1–5. In this communication, the development of a simple, efficient, scalable, and stereocontrolled synthesis of 6 is reported, leading to the preparation of axinellamines on a gram scale. In a more general sense, three distinct and enabling methodological advances were made during these studies, as outlined in detail below.

Figure 1.

Structures of axinellamines A & B, massadine, massadine chloride, and palau’amine and Retrosynthetic analysis.

At the heart of the retrosynthetic plan (Figure 1) of spiroaminoketone 6 is the speculation that allylic guanidine 7 may undergo a stereoselective chlorination/spirocyclization process, presumably due to the steric interaction between the Cl+ source and the neighboring methylene azide functionality. This disconnection clears the two most challenging stereocenters of the fully substituted cyclopentane framework. Allylic guanidine 7 may arise from the stereoselective condensation of a putative allylic anion intermediate 8 with an appropriate side chain segment. The strategic inclusion of this C2-symmetric intermediate in the synthetic design is advantageous and fully exploits the hidden symmetry in this class of natural products5 as it not only eliminates the regioselectivity issue during the sidechain installation step, but also renders the stereochemistry of the corresponding allylic chloride 9 irrelevant. Allylic chloride 9 could arise from cyclopentenone 10, which in turn could be accessed via a Pauson-Khand cycloaddition between propargyl guanidine 11 and bis-allylic azide 12.

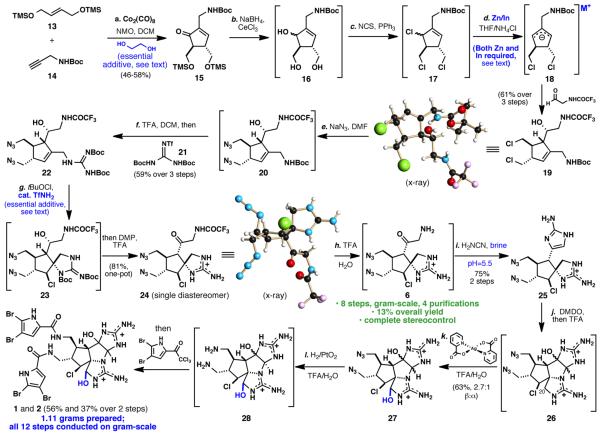

Initial forays based on this blueprint revealed that 11 possessed only marginal reactivity under the most common Pauson-Khand reaction conditions and 12 completely decomposed for most of the cases (perhaps due to the known rearrangement of allylic azides6). Thus, bis-allylic trimethyl silyl ether 13 and propargyl amine 14 were employed. Initial trials under thermal conditions with cyclohexyl amine,7a BuSMe,7b DMSO,7c and water7d as additive only led to decomposition of the Co complex of 14.

Under the mediation of N-oxides such as NMO,7e and TMANO,7f the desired product 15 was produced in only 15-25% yield. After extensive experimentation,8 it was identified that the combination of ethylene glycol and NMO dramatically improved the performance of this transformation, generating the desired cyclopentenone 15 reproducibly in 46-58% yield (6.2 gram scale). In light of the fact that intermolecular Pauson-Khand reactions of unactivated alkenes are rare and involve reaction partners without useful functional groups,7 the discovery of this ethylene glycol-assisted condition is notable. Studies are underway to evaluate both the scope and mechanistic origin of this new protocol.

With the scalable formation of cyclopentenone 15 secured, subsequent Luche reduction was performed to effect the 1,2-redution and desilylation in one-pot (6.2 gram scale). The resulting triol 16 (not purified) was converted to the corresponding trichloride 17 as an inconsequential mixture (2:1) of diastereomers. After filtration through a short silica plug, trichloride 17 was determined to be pure enough for the subsequent sidechain installation without additional purification. At this juncture conditions for the speculative desymmetrizing Barbier reaction to access 19 needed to be developed. While initial trials using Zn, In, Sn, and Fe under anhydrous conditions9a failed to produce any desired product, it was discovered that the combination of Zn and saturated NH4Cl9b successfully produced 19, albeit in low yield. After extensive optimization, it was found that the combination of Zn, In and NH4Cl (6% aqueous solution) dramatically increased the reaction yield (61% overall from diol 16, 4.1 gram scale) while reducing the required reaction time. Control studies using In or InCl3 without Zn or employing Zn/Cu only produced complex mixtures or recovered starting material. To our knowledge, the synergistic combination of In and Zn in a Barbier reaction is without precedent and further studies in this and related reactions warrant further investigation.

Starting with bis-chloride 19, azide installation, Boc removal with TFA, and subsequent guanidine installation using 21 as guanidine source10 occurred smoothly to produce allylic guanidine 22 with 59% yield over three steps with only one chromatography (3.2 gram scale). The critical spirocyclization/chlorination step required extensive study. Initial attempts to convert 22 to 23 using a variety of chlorinating agents were frustratingly variable – with results differing on the batch of 22. It was eventually discovered that residual TfNH2, formed during installation of the guanidine moiety in the preceding step with reagent 21 played an enabling role in the ensuing reaction with tBuOCl delivering spirocycle 23 as a single diastereomer (ca. 85% carried in crude form to subsequent step after solvent removal). Interestingly, in the absence of TfNH2 or with excess of TfNH2, complex mixtures were obtained. Intrigued by these observations, additional studies have been carried out to understand this transformation. In a 19F NMR experiment, addition of tBuOCl to a mixture of TfNH2 and CD2Cl2 led to no observable shift of the CF3 group, which indicated that the formation of TfNHCl was unlikely. Whereas mixing of TfNH2 with allylic guanidine 22 led to no spectroscopic changes, the addition of TfNH2 to the spiro product 23 induced a dramatic shift of most of the proton signals (see SI for details). Studies are underway to further understand the origin of this dramatic effect.

Spirocycle 23 could be processed in crude form and in the same reaction vessel to ketone 24 using DMP with 10:1 DCM/TFA as solvent (81% yield from 22 to 24, 2.4 gram scale). Further treatment of purified 24 with TFA in the presence of water produced spiro-aminoketone 6 in a total of 8 steps with 4 chromatographic purifications and in 13% overall yield from 13 and 14. By comparison to our previous synthesis of 6, this route reduced the number of steps by more than half and increased the overall yield by >10-fold (63% ideality). It is worth mentioning that 2.5 grams of 6 was prepared by one chemist in a single batch within two weeks, which surpassed the entire amount of 6 that was produced during our previous studies towards this family of PIAs (~2 grams over a three year period).

Finally, in order to demonstrate that complicated tetracyclic PIAs can be prepared in large quantities with intermediate 6, the syntheses of axinellamines A & B were completed. Thus, reaction of 6 with cyanamide in brine at pH 5.5 led to 25 in 75% yield over two steps (1.9 gram scale). Oxidation of the 2-aminoimidazole with DMDO and subsequent dehydrative cyclization with TFA furnished 26 that was processed in crude form to 27-α and 27-β with silver picolinate in 63% yield over 2 steps (1.26 gram scale, 2.7:1 β:α). Conversion of the azide groups to the acylpyrrole sidechains was accomplished in a one-pot sequence involving PtO2-mediated reduction followed by acylation with 2,3-dibromo-5-trichloroacetylpyrrole to furnish 1 and 2. Over one gram of the axinellamines (0.89 and 0.22 grams of 1 and 2 respectively) have been prepared by this route – dramatically surpassing both the efficiency of our previous synthesis and isolation from natural sources.

Notable features of the stereocontrolled syntheses of 1–2 and 6 (12 and 8 steps, 4 and 7 purifications respectively), representing formal total syntheses of 3–5, include: (1) the robustness, simplicity, and practicality of the route despite the sheer complexity of 1-2: All steps are conducted on a grams-cale, none require cryogenic temperatures, and most proceed without intermediate purification or an inert atmosphere; (2) an ethylene glycol-assisted Pauson-Khand cycloaddition reaction; (3) a chemoselective In/Zn-mediated Barbier type reaction; and (4) a TfNH2-assisted chlorination-spirocyclization.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Stereocontrolled, gram-scale synthesis of the axinellamines (1 and 2).

Reagents and Conditions: a) Co2(CO)8, NMO, ethylene glycol, 4Å molecular sieves, DCM, rt, 12 h, 46-58%; b) NaBH4, CeCl3·7H2O, MeOH, 0 °C to rt, 12 h; c) PPh3, NCS, DCM, 0 °C to rt, 12 h; d) Zn, In, 2,2,2-trifluoro-N-(2-oxoethyl)-acetamide, THF, 6% aq NH4Cl, rt, 3 h, 61% for 3 steps; e) NaN3, DMF, 85°C, 16 h; f) TFA, DCM, rt; then 21, Et3N, DCM, rt, 12 h, 59% for 3 steps; g) tBuOCl, TfNH2 (0.25 eq), DCM, 0 °C; then DMP, TFA:DCM=1:10, rt, 12 h, 81%; h) TFA:H2O=1:1, 70 °C, 36 h, quantitative if isolated, carried to next step directly; i) H2NCN, brine, NaOH (pH=5.5), 70 °C, 4 h, 75% for 2 steps; j) DMDO, TFA:H2O=5:95; then TFA:DCM=1:1, rt, 24 h; k) Silver(II)picolinate, TFA:H2O=1:9, rt, 1.5 h, 63% yield over 2 steps, 2.7:1 β:α; l) H2, Pt2O, TFA:H2O=5:95, 1 h; then 2,3-dibromo-5-trichloroacetylpyrrole, DIEA (pH=8.0), MeCN, rt, 24 h, 56% and 37% over 2 steps for 1 and 2

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Prof. A. Rheingold and Dr. Curtis E. Moore for X-ray crystallographic measurements.

Funding Sources

Financial support for this work was provided by the NIH/NIGMS (GM-073949), the NSF (predoctoral fellowship to R.A.R.), Amgen, and Bristol–Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures and characterization data for all reactions and products, including copies of 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Urban S, Leone P. d. A., Carroll AR, Fechner GA, Smith J, Hooper JNA, Quinn RJ. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:731–735. doi: 10.1021/jo981034g. Nishimura S, Matsunaga S, Shibazaki M, Suzuki K, Furihata K, Van SRWM, Fusetani N. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2255–2257. doi: 10.1021/ol034564u. Grube A, Immel S, Baran PS, Koeck M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:6721–6724. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701935. Kinnel RB, Gehrken HP, Scheuer PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:3376–3377. Kinnel RB, Gehrken H-P, Swali R, Skoropowski G, Scheuer PJ. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3281–3286. For a review, see: Köck M, Grube A, Seiple IB, Baran PS. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:6586–6594. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701798.

- (2).For a comprehensive listing of studies towards the PIA family, see reference 1f and Seiple IB, Su S, Young IS, Lewis CA, Yamaguchi J, Baran PS. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:1095–1098. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907112. For recent studies, see Namba K, Inai M, Sundermeier U, Greshock TJ, Williams RM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:6557–6559. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.10.037. Feldman KS, Nuriye AY, Li J. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:5042–5060. doi: 10.1021/jo200740b. Chinigo GM, Breder A, Carreira EM. Org. Lett. 2011;13:78–81. doi: 10.1021/ol102577q. Ma Z, Lu J, Wang X, Chen C. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:427–429. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02214d.

- (3).(a) O’Malley DP, Yamaguchi J, Young IS, Seiple IB, Baran PS. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:3581–3583. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamaguchi J, Seiple IB, Young IS, O’Malley DP, Maue M, Baran PS. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:3578–3580. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Su S, Seiple IB, Young IS, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16490–16491. doi: 10.1021/ja8074852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gaich T, Baran PS. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:4657–4673. doi: 10.1021/jo1006812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Li Q, Hurley P, Ding H, Roberts AG, Akella R, Harran PG. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:5909–5919. doi: 10.1021/jo900755r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Feldman AK, Colasson B, Sharpless KB, Fokin VV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13444–13445. doi: 10.1021/ja050622q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Sugihara T, Yamaguchi M, Nishizawa M. Chem. Eur. J. 2001;7:1589–1595. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010417)7:8<1589::aid-chem15890>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brown JA, Janecki T, Kerr WJ. Synlett. 2005:2023–2026. [Google Scholar]; (c) Chung YK, Lee BY. Organometallics. 1993;12:220–223. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sugihara T, Yamaguchi M. Synlett. 1998:1384–1386. [Google Scholar]; (e) Shambayati S, Crowe WE, Schrieber SL. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:5289. [Google Scholar]; (f) Jeong N, Chung YK, Lee BY, Lee SH, Yoo S-E. Synlett. 1991:204. [Google Scholar]

- (8).For some recent reviews on the Pauson–Khand reaction, see: Omae I. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2007;21:318–344. Strübing D, Beller M. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2006;18:165–178. Pérez-Castells J. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2006:207–257. Gibson SE, Mainolfi N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:3022–3037. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462235. Boñaga LVR, Krafft ME. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:9795–9833. Blanco-Urgoiti J, Añorbe L, Pérez-Serrano L, Domínguez G, Pérez-Castells J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004;33:32–42. doi: 10.1039/b300976a. Alcaide B, Almendros P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004:3377–3383. Rivero MR, Adrio J, Carretero JC. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002:2881–2889. Brummond KM, Kent JL. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:3263–3283. Fletcher AJ, Christie SDR. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 2000:1657–1668.

- (9).(a) Blomberg C. The Barbier reaction and related one-step processes. Springer-Verlag; 1993. [Google Scholar]; (b) Breton GW, Shugart JH, Hughey CA, Conrad BP, Perala SM. Molecules. 2001;6:655–662. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Feichtinger K, Zapf C, Sings HL, Goodman M. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3804–3805. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.