Summary

The aim of this study was to identify risk factors associated with progression-free survival in patients with Ewing sarcoma undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT); 116 patients underwent ASCT in 1989-2000 and reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Eighty patients (69%) received ASCT as first-line therapy and 36 (31%), for recurrent disease. Risk factors affecting ASCT were analyzed with use of the Cox regression method. Metastatic disease at diagnosis, recurrence prior to ASCT and performance score <90 were associated with higher rates of disease recurrence/progression. Five-year probabilities of progression-free survival in patients with localized and metastatic disease at diagnosis who received ASCT as first-line therapy were 49% (95% CI 30 – 69) and 34% (95% CI 22 – 47) respectively. The 5-year probability of progression-free survival in patients with localized disease at diagnosis, and received ASCT after recurrence was 14% (95% CI 3 – 30). Progression-free survival rates after ASCT are comparable to published rates in patients with similar disease characteristics treated with conventional chemotherapy, surgery and irradiation suggesting a limited role for ASCT in these patients. Therefore, ASCT if considered should be for high-risk patients in the setting of carefully controlled clinical trials.

Keywords: Autologous transplant, Ewing sarcoma, Progression-free survival

Introduction

Ewing sarcoma is predominantly a tumor of older children and young adults with 70% of patients aged less than 21 years at diagnosis(1). Five-year event-free survival of patients with localized tumors is 69% using a combination of chemotherapy, surgery and irradiation(2). In contrast, survival for patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis or recurrent tumor is less than 40%(3-7). Other poor prognostic factors include large tumors (tumor volume >200 ml or maximal tumor diameter ≥8 cm), tumors of the axial skeleton, poor histologic response following initial chemotherapy and variant fusion transcripts(8-11). In an effort to improve progression-free survival rates in patients with known poor prognostic factors, several investigators have utilized high dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). Some of these studies reported progression-free survival rates superior to conventional therapy while in other studies survival rates were comparable to conventional treatment(12-16). The eligibility criteria for ASCT have varied and conclusions hampered by the small numbers of patients. In this report, we analyzed patients with Ewing sarcoma (N=116) treated with ASCT between 1989 and 2000 to identify risk factors influencing progression-free and overall survival.

Patients and Methods

Data Collection

Data on patients undergoing ASCT were obtained from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR). The CIBMTR comprises of a voluntary working group of more than 450 transplant centers worldwide. Data are collected on allogeneic transplants performed worldwide and autologous transplants performed in North and South America. Participating transplant centers register all transplants and provide detailed patient, disease, transplant and outcome data on a representative sample of patients, selected using a weighted randomized scheme, to a Statistical Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Compliance and data quality are monitored by computerized error checks, on-site audits and physician review of submitted data. All patients are followed longitudinally, with yearly follow-up on all surviving patients. The Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin approved this study.

Inclusion criteria

One hundred and sixteen patients with primary or recurrent Ewing sarcoma who underwent ASCT with myeloablative conditioning regimen as their first transplant in 1989 - 2000 were eligible. These patients were transplanted in 37 North American and 2 South American centers. The decision to offer ASCT and all aspects of conditioning regimens and supportive care were at the discretion of the transplant centers. Patients who received planned second ASCT were excluded.

Study Endpoints

Hematopoietic recovery was defined as achieving an absolute neutrophil count ≥0.5 × 109/L and platelets ≥20 × 109/L, unsupported for 7 days. Transplant-related mortality was defined as death in the first 28 days after transplant or death occurring beyond this period in the absence of persistent disease, recurrence or tumor progression. Relapse or progression, were defined as disease recurrence or progressive disease occurring beyond 28 days after transplantation. Survival without recurrence or tumor progression, as detected by physical examination and/or radiography was defined as progression-free survival.

Statistical Methods

Univariate probabilities of neutrophil recovery, platelet recovery, transplant-related mortality and relapse or progression were calculated using cumulative incidence estimator(17). For neutrophil and platelet recovery, death without the event was the competing risk. For transplant-related mortality, relapse or progression was the competing risk and for relapse or progression, transplant-related mortality was the competing risk. Univariate probabilities of progression-free and overall-survival were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator(18). For progression-free survival, recurrence or progression of disease or death from any cause was considered an event. Patients surviving without recurrence or progression were censored at the date of last contact. For overall survival, death from any cause was considered an event. Surviving patients were censored at the date of last contact. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using log transformation.

Cox proportional hazards regression models were constructed for transplant-related mortality, relapse/progression and overall mortality(19). Models were built using a forward stepwise selection process and variables that attained a p-value ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant and held in the final model. The following variables were tested: age (≤10 vs. 11 - 20 vs. 21 – 30 vs. >30 years), gender, performance score (90 - 100 vs. <90), sites of tumor involvement at diagnosis (central or multi-focal vs. extremity or local vs. metastatic tumor), tumor recurrence or progression prior to ASCT, year of transplant (1989-1995 vs. 1996-2000) and conditioning regimen (TBI vs. non-TBI containing). The assumption of proportional hazards was tested using time-dependent covariates and graphical methods(20). All variables met the proportional hazards assumption. We did not observe a significant center effect on transplant-outcome (21). All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute, Carey, NC).

Results

Patient, disease and transplant characteristics

Patient, disease, and transplant characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age at ASCT was 18 years. Fifty-four of 116 patients (47%) had localized disease at diagnosis and 55 (47%), metastatic disease. The extent of tumor at diagnosis was not available for 7 patients. Of the 54 patients with localized tumor at diagnosis, 27 underwent ASCT as first-line therapy (10 in complete and 17 in partial remission) and 27 after relapse. In the latter group, 14 achieved complete remission, 9 achieved partial remission, 3 stable and 1 progressive disease at ASCT. For the 55 patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis, 50 patients underwent ASCT as first-line therapy (25 in complete remission, 21 in partial remission and 4 with stable disease at ASCT) and 5 after relapse (all 5 patients were in complete remission at ASCT). The median time from diagnosis to ASCT as first-line therapy was 6 months. For patients transplanted after initial relapse, the median time to first recurrence in patients with local and metastatic disease at diagnosis were 13 months and 6 months, respectively; the median time from recurrence to ASCT was 5 months in this group. One third of patients had performance scores <90 at transplantation. Peripheral blood was the predominant graft used and half of patients received conditioning regimens without total body irradiation (TBI). Of these, melphalan-containing regimens were the most frequently used. Among recipients of TBI-containing (n=46), most received TBI with cyclophosphamide and etoposide (n=22), or with etoposide and melphalan (n=21). Only 19 patients (16%) had additional planned therapy after ASCT. This included surgery in all 19 patients and irradiation to the tumor site in 10 patients. The median follow-up of survivors was 57 (range, 16-133) months with only one surviving patient followed for less than 2 years.

Table 1.

Patient, disease and transplant characteristics

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 116 |

| Male sex | 78 (67) |

| Age at transplant, years | |

| ≤10 | 17 (15) |

| 11-20 | 68 (59) |

| 21-30 | 18 (15) |

| 31-40 | 9 (8) |

| 41-50 | 4 (3) |

| Primary site of tumor | |

| Extremity | |

| Distal | 35 (30) |

| Proximal | 9 (8) |

| Central | |

| Pelvis | 32 (27) |

| Chest | 24 (21) |

| Spine/paravertebral | 13 (11) |

| Head/Neck | 1 (1) |

| Multifocal | 2 (2) |

| Extent of tumor at diagnosis | |

| Local | 54 (47) |

| With metastases* | 55 (47) |

| Unknown | 7 (6) |

| Relapse prior to BMT | 36 (31) |

| Disease status at transplant | |

| Complete remission | 57 (49) |

| Partial remission | 49 (42) |

| Stable disease | 8 (7) |

| Progressive disease | 2 (2) |

| Year of transplant | |

| 1989 - 1995 | 35 (30) |

| 1996 - 2000 | 81 (70) |

| Karnofsky/Lansky performance score pre-transplant | |

| <90 | 38 (33) |

| ≥90 | 74 (64) |

| Unknown | 4 (3) |

| Graft type | |

| Bone marrow | 26 (22) |

| Peripheral blood† | 84 (73) |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| Total body irradiation + other | 59 (51) |

| Non total body irradiation | |

| Busulfan + cyclophosphamide | 1 (1) |

| Busulfan + melphalan±other | 11 (9) |

| Melphalan + other (not busulfan) | 31 (27) |

| Cyclophosphamide + etoposide ± other | 14 (12) |

Sites of metastases: Lung ± other (excluding BM): N=34; BM ± other: N=13; other sites: N=8

9 peripheral blood grafts were CD34 selected

Hematopoietic recovery

Nearly all patients achieved neutrophil and platelet recovery after ASCT. The median times to neutrophil and platelet recoveries were 12 days and 22 days, respectively. The day-28 probability of neutrophil recovery was 92% (95% CI, 86 - 96). The day-100 probability of platelet recovery was 89% (95% CI, 82 - 94). Three patients failed to achieve hematopoietic recovery; all received peripheral blood grafts, 2 were in partial remission and 1 in complete remission at ASCT.

Transplant-related mortality

In multivariate analysis, none of the factors examined were predictive of transplant-related mortality. The day-100 and 1-year probabilities of transplant-related mortality were 4% (95% CI) and 9% (95% CI), respectively.

Relapse or progression

Relapse or progression rates were higher in patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis, recurrent disease prior to transplantation and performance score <90 (Table 2). In general, recurrence after ASCT occurred early; the median time to recurrence was 6 months (range 1 – 73). The 5-year probabilities of relapse or progression for patients with localized and metastatic disease who received ASCT as first-line therapy were 51% (95% CI 30 - 71) and 60% (95% CI 44 - 75), respectively. The 5-year probability of relapse or progression for patients with localized disease who relapses prior to ASCT was 75% (95% CI 50 - 93). Among the 5 patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis who received their ASCT after relapse, 4 patients had recurrent disease post-transplantation.

Table 2.

Results of mulitvariate analysis showing significant risk factors affecting relapse/progression, treatment failure and overall mortality after transplantation

| Outcome | N | Relative Risk 95% confidence interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse/progression | |||

| Performance score | |||

| 90 - 100 | 78 | 1.00 | |

| <90 | 38 | 1.79 (1.05 - 3.02) | 0.031 |

| Initial extent of tumor | |||

| Localized | 54 | 1.00 | |

| Metastatic | 55 | 1.83 (1.02 - 3.27) | 0.042 |

| Relapse prior to BMT | |||

| No | 80 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 36 | 2.34 (1.32 - 4.15) | 0.004 |

| Treatment failure | |||

| Performance score | |||

| 90 - 100 | 78 | 1.00 | |

| <90 | 38 | 1.99 (1.20 - 3.28) | 0.007 |

| Initial extent of tumor | |||

| Localized | 54 | 1.00 | |

| Metastatic | 55 | 1.95 (1.11 - 3.41) | 0.020 |

| Relapse prior to BMT | |||

| No | 80 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 36 | 2.51 (1.45 - 4.35) | 0.001 |

| Overall mortality | |||

| Performance score | |||

| 90 - 100 | 78 | 1.00 | |

| <90 | 38 | 1.67 (1.01 - 2.77) | 0.048 |

| Relapse prior to BMT | |||

| No | 80 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 36 | 2.41 (1.34 - 4.35) | 0.003 |

Treatment failure

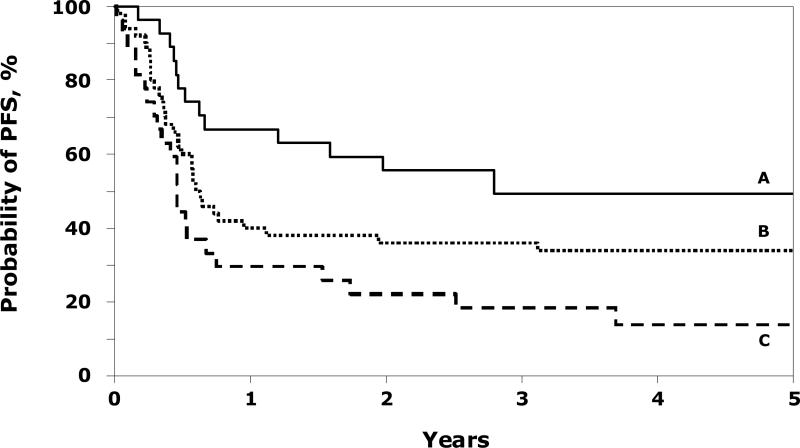

Treatment failure rates (relapse/progression or death, inverse of progression-free survival) were higher in patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis, recurrent disease prior to transplantation and performance score <90 (Table 2). We were unable to examine a detailed effect of conditioning regimens used other than TBI regimens compared to non-TBI regimens (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.50 – 1.26, p=0.332). The site of tumor at diagnosis (extremity versus central) did not affect progression-free survival after ASCT (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.70 – 1.77, p=0.654). The 5-year probabilities of progression-free survival were 49% (95% CI 30 - 69) and 34% (95% CI 22 - 47) for patients with localized and metastatic disease respectively, who received ASCT as first-line therapy (Figure 1). The corresponding probability for patients with localized disease who received ASCT after a recurrence was 14% (95% CI 3 – 30). Among the 5 patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis who received their ASCT after relapse, 1 patient remains disease-free and alive post-transplantation. We were unable to demonstrate significant differences in progression-free survival rates in patients with very good response and partial response pre-ASCT. Use of CD34 selected peripheral blood grafts was not associated with progression-free survival.

Figure 1.

Probability of progression-free survival (PFS) after ASCT by disease stage and disease status: A=patients with local disease and received ASCT as first line therapy (49% @ 5 years); B=patients with metastatic disease and received ASCT as first line therapy (34% @ 5 years) and C=patients with local disease and received ASCT after recurrence (14% @ 5 years).

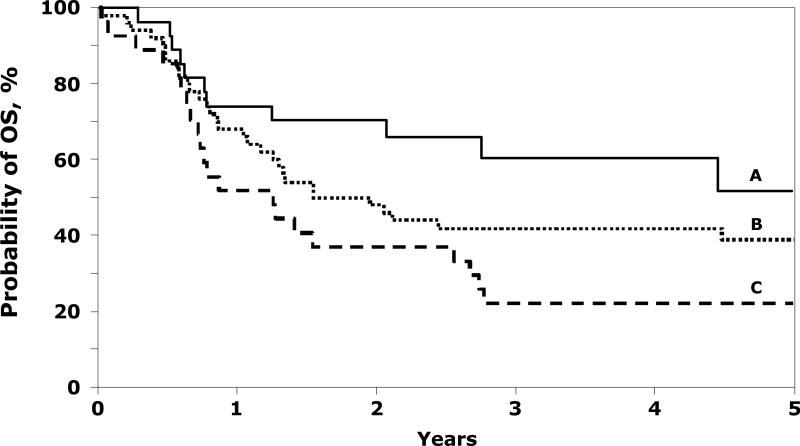

Overall mortality

Seventy-two of 116 (62%) patients died after ASCT. Mortality was higher in patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis, patients who had a recurrence prior to transplantation and performance score <90 (Table 2). The 5-year probabilities of overall survival were 52% (95% CI 29 - 74) and 39% (95% CI 26 - 53) for patients with localized and metastatic disease respectively who received ASCT as first-line therapy (Figure 2). The corresponding probability for patients with initial localized disease who received ASCT after a recurrence was 22% (95% CI 11 - 40). Recurrent disease was the cause of death in 91% of fatalities (n=61). Other causes of death included infection (n=3), organ failure (n=1), interstitial pneumonitis (n=1), second malignancy (n=1) and not reported (n=5).

Figure 2.

Probability of overall survival (OS) after ASCT by disease stage and disease status: A=patients with local disease and received ASCT as first line therapy (52% @ 5 years); B=patients with metastatic disease and received ASCT as first line therapy (39% @ 5 years) and C=patients with local disease and received ASCT after recurrence (22% @ 5 years).

Discussion

The prognosis of patients with metastatic or recurrent Ewing sarcoma is poor. We report outcome after ASCT in a large cohort of higher risk patients with Ewing sarcoma who received this therapy as first-line or for recurrent disease. We observed progression-free survival rates of 49% in patients with localized disease and 34% in those with metastatic disease when ASCT was offered as first-line therapy. These rates are comparable to published progression-free survival rates after conventional therapy (chemotherapy, surgery and irradiation) in patients with similar disease characteristics though the recent addition of ifosfamide and etopside to conventional therapy has resulted in higher progression-free survival rates in patients with local disease(2, 4). Further, progression-free survival rates reported in the current study where patients received ASCT at several institutions over a decade are comparable to those reported by others(22, 23) and suggest that the results of these smaller prospective trials are generalizable to the results of ASCT as practiced by the North American transplant community.

Most patients with recurrent disease prior to transplantation achieved a complete or partial remission prior to ASCT. Despite this, their long-term outcome was poor. The 5-year progression-free survival rate was only 14% for patients who relapsed prior to ASCT regardless their initial disease was localized. Our observations are similar to other published reports(6, 7, 14, 15). In the current report, only 5 patients with metastatic disease underwent ASCT after an initial relapse, and 4 of these patients had a recurrence after ASCT. We were unable to examine the effect of duration of first remission, a known predictor of survival after recurrence(6).

Two papers have reported better outcomes after ACST with busulfan and melphalan containing conditioning regimens: progression-free survival rates were 50-60% despite the inclusion of patients with metastatic disease at presentation(14, 15). One of these reports described 21 and the other 18 patients. In a larger series from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 50 patients with Ewing sarcoma received a TBI and melphalan conditioning regimen with 5-year progression-free survival rates of 21% for patients with metastatic disease transplanted in first remission and 32% for those transplanted in second remission(16). The higher progression-free survival rate is due to most patients having had local disease at diagnosis. Though over half of patients in the current report received a non-TBI conditioning regimen, because of the heterogeneity of conditioning regimens used, we were only able to examine the use of TBI regimens versus non-TBI regimens and found that this did not significantly affect progression-free survival.

Consistent with other reports(4, 7), patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis and recurrence prior to ASCT were more likely to have a second recurrence of their tumor shortly after ASCT. Additionally, patients with a performance score <90 (presumably a surrogate for metastatic tumor, recurrent tumor or heavy pre-treatment) fared poorly. Disease progression or recurrence, transplant-related and overall mortality rates were higher in these patients. We did not observe an adverse impact of tumor site on outcome after ASCT. However, most patients in the current report were high-risk as defined by the presence of metastatic disease at diagnosis or recurrence prior to ASCT. We did not observe differences in progression-free survival rates by tumor site at diagnosis. Shankar and colleagues also observed this in their patients with relapsed Ewing sarcoma(6). In the absence of tumor recurrence, patients with extremity tumors at diagnosis have higher progression-free survival rates than those with tumors of the axial skeleton(1, 6). It is likely that when tumor recurs, disease characteristics considered favorable at diagnosis are no longer relevant, and recurrence and associated characteristics like the duration of first remission become dominant prognostic features. In patients who recurred prior to ASCT, small numbers prevented us from examining disease recurrence and progression-free survival after ASCT.

As with any study that utilizes an observational database, ours has several limitations. These include: 1) patient selection and decision to offer ASCT, 2) heterogeneity of treatments prior to ASCT, 3) heterogeneity of transplant-conditioning regimens and 4) other unknown and unmeasured factors that may influence outcomes after ASCT. Further, we do not collect data on tumor size, histologic response to chemotherapy, fusion transcripts and the interval from diagnosis to relapse in patients who received ASCT as second-line therapy.

We observed 5-year progression-free survival rates of 34% in patients with metastatic disease who received ASCT as first-line therapy. This is similar to progression-free survival rates of 29% after conventional therapy (4) and ASCT appear to offer no additional advantage in this group of patients. For patients with local disease, the addition of ifosfamide and etoposide to conventional therapy has led to progression-free survival rates of 70%, whereas we observed lower rates (49% at 5-years). This is sobering considering patients enrolled on clinical trials are subject to intent-to-treat analysis whereas the population in this report was analyzed from time of transplantation. The role of ASCT can only be addressed satisfactorily when patients with similar disease characteristics are randomized to receive one of two treatment options. Currently an international collaborative randomized trial is examining the role of ASCT and conventional therapy in patients with high-risk Ewing sarcoma (Euro E.W.I.N.G 99). Patients with local tumor or pleural/pulmonary metastases are randomized to receive ASCT or continuing chemotherapy after induction therapy and surgical resection of primary tumor. Patients with local tumor ± pleural/pulmonary metastases are eligible if their tumor volume is ≥200 ml or if they have a poor histologic response to induction chemotherapy (≥10% viable cells) independent of tumor volume or metastases to the pleura or lung. Given the poor outcome with metastatic or recurrent Ewing sarcoma, ASCT should be offered to patients enrolled on clinical trials that examine the various therapies in a randomized manner.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Public Health Service Grant U24-CA76518 from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; Office of Naval Research; Health Services Research Administration (DHHS); and grants from AABB; Abbott Laboratories; Aetna; American International Group, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; AnorMED, Inc.; Astellas Pharma US, Inc.; Baxter International, Inc.; Berlex Laboratories, Inc.; Biogen IDEC, Inc.; BioOne Corporation; Blood Center of Wisconsin; Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; Bone Marrow Foundation; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Cangene Corporation; Celgene Corporation; CellGenix, GmbH; Cerus Corporation; Cylex Inc.; CytoTherm; DOR BioPharma, Inc.; Dynal Biotech, an Invitrogen Company; EKR Therapeutics; Enzon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Gambro BCT, Inc.; Gamida Cell, Ltd.; Genzyme Corporation; Gift of Life Bone Marrow Foundation; GlaxoSmithKline, Inc.; Histogenetics, Inc.; HKS Medical Information Systems; Hospira, Inc.; Kiadis Pharma; Kirin Brewery Co., Ltd.; Merck & Company; The Medical College of Wisconsin; Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Miller Pharmacal Group; Milliman USA, Inc.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; MultiPlan, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Nature Publishing Group; Oncology Nursing Society; Osiris Therapeutics, Inc.; Pall Life Sciences; PDL BioPharma, Inc; Pfizer Inc; Pharmion Corporation; Roche Laboratories; Sanofi-aventis; Schering Plough Corporation; StemCyte, Inc.; StemSoft Software, Inc.; SuperGen, Inc.; Sysmex; Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; The Marrow Foundation; THERAKOS, Inc.; University of Colorado Cord Blood Bank; ViaCell, Inc.; Vidacare Corporation; ViraCor Laboratories; ViroPharma, Inc.; Wellpoint, Inc.; and Zelos Therapeutics, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ginsberg JP, Woo SY, Johnson ME, Hicks MJ, Horowitz ME. Pizzo and Poplack. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2002. Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors: Ewing's sarcoma of bone soft tissue and the peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors. pp. 973–1016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grier HE, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, Link MP, Fryer CJ, Pritchard DJ, et al. Addition of ifosfamide and etoposide to standard chemotherapy for Ewing's sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:694–701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cangir A, Vietti TJ, Gehan EA, Burgert EO, Jr., Thomas P, Tefft M, et al. Ewing's sarcoma metastatic at diagnosis. Results and comparisons of two intergroup Ewing's sarcoma studies. Cancer. 1990;66:887–93. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900901)66:5<887::aid-cncr2820660513>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miser JS, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, Link MP, Fryer CJ, Pritchard DJ, et al. Treatment of metastatic Ewing's sarcoma or primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone: evaluation of combination ifosfamide and etoposide--a Children's Cancer Group and Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2873–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paulussen M, Ahrens S, Craft AW, Dunst J, Frohlich B, Jabar S, et al. Ewing's tumors with primary lung metastases: survival analysis of 114 (European Intergroup) Cooperative Ewing's Sarcoma Studies patients. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3044–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shankar AG, Ashley S, Craft AW, Pinkerton CR. Outcome after relapse in an unselected cohort of children and adolescents with Ewing sarcoma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2003;40:141–7. doi: 10.1002/mpo.10248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Galindo C, Billups CA, Kun LE, Rao BN, Pratt CB, Merchant TE, et al. Survival after recurrence of Ewing tumors: the St Jude Children's Research Hospital experience, 1979-1999. Cancer. 2002;94:561–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahrens S, Hoffmann C, Jabar S, Braun-Munzinger G, Paulussen M, Dunst J, et al. Evaluation of prognostic factors in a tumor volume-adapted treatment strategy for localized Ewing sarcoma of bone: the CESS 86 experience. Cooperative Ewing Sarcoma Study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;32:186–95. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199903)32:3<186::aid-mpo5>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wunder JS, Paulian G, Huvos AG, Heller G, Meyers PA, Healey JH, et al. The histological response to chemotherapy as a predictor of the oncological outcome of operative treatment of Ewing sarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1020–33. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199807000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Alava E, Kawai A, Healey JH, Fligman I, Meyers PA, Huvos AG, et al. EWS-FLI1 fusion transcript structure is an independent determinant of prognosis in Ewing's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1248–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zoubek A, Dockhorn-Dworniczak B, Delattre O, Christiansen H, Niggli F, Gatterer-Menz I, et al. Does expression of different EWS chimeric transcripts define clinically distinct risk groups of Ewing tumor patients? J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1245–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.4.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burdach S, Jurgens H, Peters C, Nurnberger W, Mauz-Korholz C, Korholz D, et al. Myeloablative radiochemotherapy and hematopoietic stem-cell rescue in poor-prognosis Ewing's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1482–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraser CJ, Weigel BJ, Perentesis JP, Dusenbery KE, DeFor TE, Baker KS, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for high-risk Ewing's sarcoma and other pediatric solid tumors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:175–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drabko K, Zawitkowska-Klaczynska J, Wojcik B, Choma M, Zaucha-Prazmo A, Kowalczyk J, et al. Megachemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in children with Ewing's sarcoma. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9:618–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atra A, Whelan JS, Calvagna V, Shankar AG, Ashley S, Shepherd V, et al. High-dose busulphan/melphalan with autologous stem cell rescue in Ewing's sarcoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;20:843–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladenstein R, Lasset C, Pinkerton R, Zucker JM, Peters C, Burdach S, et al. Impact of megatherapy in children with high-risk Ewing's tumours in complete remission: a report from the EBMT Solid Tumour Registry. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:697–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein JP, Rizzo JD, Zhang MJ, Keiding N. Statistical methods for the analysis and presentation of the results of bone marrow transplants. Part 2: Regression modeling. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:1001–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan E. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Therneau T, Grambasch P. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. Springer Verlag; New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen PK, Klein JP, Zhang MJ. Testing for centre effects in multi-centre survival studies: a Monte Carlo comparison of fixed and random effects tests. Stat Med. 1999;18:1489–500. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990630)18:12<1489::aid-sim140>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horowitz ME, Kinsella TJ, Wexler LH, Belasco J, Triche T, Tsokos M, et al. Total-body irradiation and autologous bone marrow transplant in the treatment of high-risk Ewing's sarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1911–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.10.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyers PA, Krailo MD, Ladanyi M, chan KW, Sailer SL, Dickman PS, et al. High-dose melphalan, etoposide, total-body irradiation, and autologous stem-cell reconstitution as consolidation therapy for high-risk Ewing's sarcoma does not improve prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2812–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]