Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO), a potent vasodilator and nontraditional neurotransmitter, is an important mediator of the changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) associated with increased neuronal activity (neurovascular coupling). In the present work, we investigated the role of NO and of its newly recognized precursor, nitrite, in neurovascular coupling using a well-established rat model of somatosensory stimulation. Biological synthesis of NO of neuronal origin was inhibited pharmacologically. Following the initial uncoupling of neuronal and hemodynamic responses to somatosensory stimulation, the NO donor sodium nitroprusside, added within the range of physiological concentrations, significantly increased, but did not fully restore the functional CBF response. In contrast, nitrite at its physiological concentration fully recovered neurovascular coupling to its original magnitude. The magnitude of the effect is, however, dose-dependent. Sub-physiological concentrations of nitrite were not enough to entirely restore neurovascular coupling and supra-physiological concentrations acted more as a local vasodilator that changed resting CBF and interfered with the functional CBF response. These results suggest that nitrite can be efficiently converted into NO and utilized to support normal cerebrovascular physiology.

Keywords: cerebral blood flow, functional hyperemia, nitrite, nitric oxide, neurovascular coupling, nNOS inhibition

1. Introduction

It has been long known that local neuronal activity is tightly coupled to the local regulation of cerebral blood flow (CBF) via complex vasoactive mechanisms collectively called neurovascular coupling. The purpose of neurovascular coupling is to ensure that homeostasis of the delicate cellular environment is maintained at all times. This is achieved through an integrated action of neurons, glial cells and blood vessels, which form a “neurovascular unit” acting at the cellular level to regulate local CBF (Attwell et al., 2010; Cauli and Hamel, 2010; Iadecola, 2004). Disruption of these mechanisms causes brain dysfunction and disease (Girouard and Iadecola, 2006), making research on the mechanisms of neurovascular coupling extremely relevant to human healthcare. Furthermore, neurovascular coupling forms the physiological basis of functional neuroimaging methods that use changes in CBF and oxygenation as surrogate markers of neural activity, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, diffuse optical imaging, positron emission tomography. Understanding the mechanisms of CBF control is critical to the interpretation and application of functional neuroimaging to brain studies.

It is generally agreed that the primary signal in the neurovascular response cascade is the release of neurotransmitter glutamate by active excitatory neurons followed by a stimulation of various neurochemical pathways (Attwell et al., 2010) and the release of key vasoactive agents, including nitric oxide (NO) or prostaglandins (Attwell et al., 2010; Cauli and Hamel, 2010; Girouard and Iadecola, 2006). NO is an ubiquitous gas that is endogenously catalyzed from the conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline by nitric oxide synthase (NOS), an enzyme that is expressed constitutively in neurons (nNOS) and endothelial cells (eNOS). In the NO hypothesis (Drake and Iadecola, 2007; Iadecola, 1993), glutamate binds to NMDA receptors located on cortical nNOS expressing interneurons and opens Ca2+ channels. Influx of Ca2+ causes activation of nNOS inside these neurons and production of NO. NO diffuses out of the neurons and acts on smooth muscle cells in local arterioles and pial arteries to cause vasodilatation. NO may also act on pericytes surrounding terminal arterioles and capillaries (Hamilton et al., 2010). A variation of this hypothesis considers first activation of astrocytes though the primary excitatory neurons and the release of NO from astrocyte end-foot, which are in contact with blood vessels in the brain (Toda et al., 2009). Finally, as another consideration, NO released by nitrergic neurons could also directly dilate blood vessels (Toda and Okamura, 2003).

Endothelial cells are another major source of NO in the brain (Garthwaite, 2008). Regardless of its source, general agreement exists that NO is deeply involved in neurovascular coupling (Iadecola, 1993). However, further investigation is still needed to fully elucidate its specific role as an obligatory mediator or as a permissive modulator, as well as its cellular origin (Lindauer et al.; Yang and Iadecola, 1997).

Even much less is known about the activity and role of the direct metabolic precursor of NO, nitrite, in brain tissue. Only recently nitrite was found to have a direct effect on resting CBF in a rat model (Rifkind et al., 2007) and in older adults high-nitrate diet increased cerebral perfusion in white matter of frontal lobe, presumably via nitrate-nitrite-NO conversion pathway (Presley et al., 2011). Nitrite is a permanent constituent of blood in all animal species at concentrations that vary considerably with diet. In human blood there is ~150-300nM of nitrite (Dejam et al., 2005), similar to the blood concentration found in rats (Kleinbongard et al., 2003). Nitrite concentrations in different mammalian tissues are in general in micromolar range of 0.5-20μM (Feelisch et al., 2008; Samouilov et al., 2007). There are many metabolic pathways by which nitrite can be converted into NO, including the nitrite reductase activity of deoxyhemoglobin (Cosby et al., 2003; Dejam et al., 2005; van Faassen et al., 2009), xanthine oxidase (XO) (Li et al., 2008), aldehyde oxidase (AO) (Li et al., 2009) and carbonic anhydrase (CA) (Aamand et al., 2009), in addition to that of all isoforms of NOS (Mikula et al., 2009). Also, nitrite can be converted into NO by direct acidic disproportioning (Millar, 1995), taking into account the observation that the brain is the organ with the highest levels of ascorbic acid in the body - up to 10mM (Harrison and May, 2009).

In spite of the reported role of nitrite in increasing resting CBF (Rifkind et al., 2007), its role in neurovascular coupling has not been examined. In the present study, we investigated whether nitrite could serve as a physiological source of NO in neurovascular coupling. In a well-established rat model of somatosensory stimulation, CBF and somatosensory evoked potentials (SEP) were recorded in α-chloralose anesthetized rats via LDF and EEG, respectively, before and after pharmacological inhibition of nNOS and during superfusion of nitrite or of the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (SNP) through a closed cranial window preparation.

2. Results

2.1. Animal Physiology

The animals were maintained under normal physiologic conditions by careful and continuous monitoring and control of the ventilation parameters, rectal temperature, arterial blood pressure, heart rate, and arterial blood gases. Arterial blood gases were assessed periodically throughout the duration of the experiments, and did not vary in result of the pharmacological manipulations (Table 1). Table 1 also shows the mean arterial blood pressure at each of the different pharmacological conditions, averaged across subjects. There was a slight – but not significant – increase in MABP following 7NI bolus administration, in accordance with earlier reports (Cholet et al., 1997; Stefanovic et al., 2007). However, in the LDF experiments, SNP and nitrite were superfused locally and produced no further effects on MABP (data not shown).

Table 1.

Values of physiological parameters at the beginning and end of experiments (n= 23).

| start | end | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| average | stdev | average | stdev | |

| MAP (mmHg) | 114 | 30 | 115 | 49 |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 112 | 10 | 117 | 23 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 41 | 6 | 38 | 5 |

| pH | 7.38 | 0.07 | 7.37 | 0.04 |

2.2. Laser Doppler flowmetry

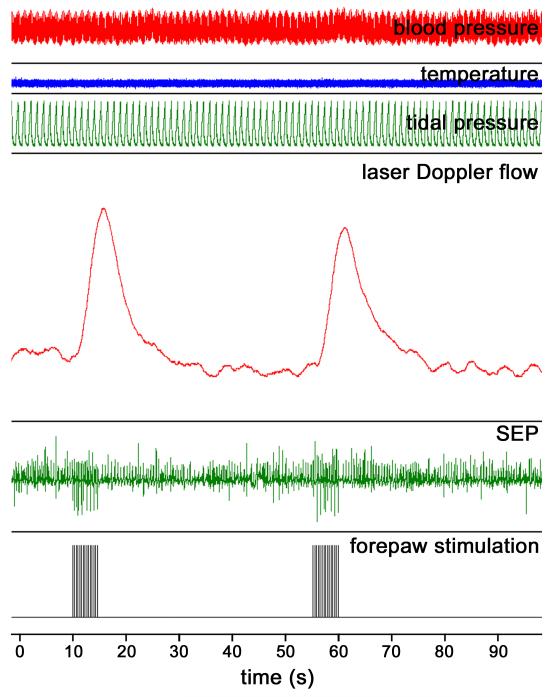

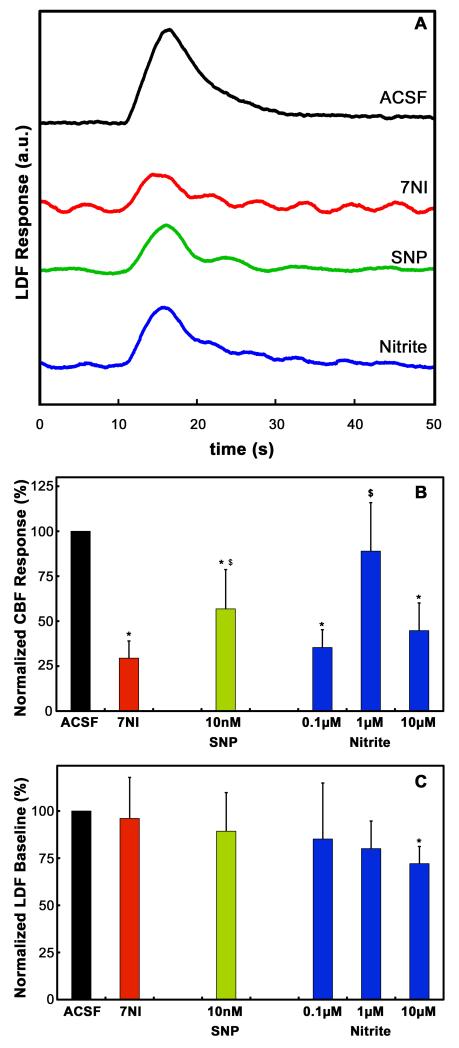

Figure 1 shows a typical screenshot of all the important parameters continuously recorded by the BIOPAC during the LDF experiments. Electrical stimulation of the forepaw elicited robust LDF and SEP responses prior to the pharmacological manipulations. Figure 2A shows the mean LDF time-courses recorded from a typical subject and averaged across the multiple stimulation epochs for each of the different pharmacological conditions. Somatosensory stimulation elicited a robust CBF response prior to the pharmacological manipulation. Following 7NI administration, a significant attenuation of the CBF response was observed, and it was accompanied by the appearance of periodic oscillations probably related to vasomotion. Topical superfusion of the NO compounds SNP or nitrite caused significant recuperation of the amplitude of the CBF response.

Figure 1.

Typical screenshot of the physiological parameters monitored with the BIOPAC during the LDF experiments. From top to bottom, traces show the blood pressure (mm Hg), rectal temperature (°C), tidal respiratory pressure (cm H2O), laser-Doppler flux (a.u.), somatosensory evoked potentials (mV) and the forepaw stimulation (mA). Forepaw stimulation elicited significant LDF and SEP responses. The LDF response was calculated from the area under the LDF curve.

Figure 2.

(A) Averaged LDF traces obtained from a typical subject during the different pharmacological conditions. The LDF response obtained during superfusion of the cranial window with ACSF (black trace) was significantly attenuated by systemic administration of 7NI (red trace). Topical administration of either SNP (green trace) or nitrite (blue trace) significantly recovered the 7NI-attenuated LDF response. (B) CBF responses obtained during the different pharmacological conditions, individually normalized to the response obtained during ACSF superfusion and averaged across subjects (n = 9-13). Systemic administration of 7NI caused a significant attenuation of the CBF response obtained during ACSF superfusion. Superfusion of the cranial window with SNP caused partial recovery of the attenuated CBF response. On the other hand, nitrite, superfused at the concentration of 1 μM, fully recovered the CBF response back to its pre-7NI value. * = p < 0.05 versus CBF response during ACSF superfusion; $ = p < 0.05 versus CBF response following 7NI administration. (C) Baseline LDF values at different pharmacological conditions, individually normalized to the baseline during ACSF superfusion and averaged across subjects. There was no effect of either 7NI, SNP of nitrite at 0.1 μM and 1 μM on the LDF baseline. However, a significant decrease of the LDF baseline was observed following superfusion with 10 μM nitrite. * = p < 0.05 versus LDF baseline during ACSF superfusion.

To quantify the LDF data, we computed the integral functional CBF response, defined as the area under the LDF time course as illustrated on Fig. 1 (Bakalova et al., 2001). Fig. 2B shows the mean area under the LDF curve, normalized to their respective pre-drug baseline condition (superfusion with ACSF) and averaged across subjects, obtained at the different pharmacological conditions. As expected, the largest response to stimulation was observed during superfusion of the cranial window with ACSF. Inhibition of nNOS following systemic 7NI administration resulted in a significant decrease of the LDF response to 29.5 ± 9.5 % of its original value (p < 0.05). Superfusion of the cranial window with the NO donor SNP caused a significant increase in the LDF response relative to the attenuated value measured following 7NI administration (p < 0.05). The LDF response to superfusion of the cranial window with 10 nM SNP recovered to 56.8 ± 21.9 % of the original response (p < 0.05). As well, superfusion of the cranial window with the NO precursor nitrite caused a significant increase in the LDF response relative to the attenuated value measured following 7NI administration (p < 0.05). Three doses of nitrite were tested (Fig. 2B). The LDF response to superfusion of the cranial window with 0.1 μM recovered to 35.3 ± 9.9 %. The dose of 1 μM increased the LDF response to 88.9 ± 27 %, which is significantly higher than the response following the 0.1 μM dose (p<0.05), but not significantly different from the original baseline value (p>0.1). Finally, when the concentration of 10 μM was used, the LDF response reduced to 44.8 ± 15.4 %, significantly less than the LDF response to the 1 μM dose suggesting a non-specific nitrite effect.

To check for a possible effect of nitrite on resting CBF, we kept track of the pre-stimulus resting LDF values (Fig. 2C). Briefly (see Experimental Procedures), each stimulus epoch was comprised of a pre-stimulus period of 10s, during which baseline resting LDF was acquired and used to normalize the LDF time-courses. Fig. 2C shows the LDF pre-stimulus baseline, individually normalized to the baseline during ACSF superfusion and averaged across subjects, at each of the pharmacological conditions. As seen in the data in Figure 2C, neither 7NI nor SNP changed the LDF baseline. As well, the LDF baseline during administration of 0.1 μM or 1 μM nitrite was not significantly different from the baseline during ACSF superfusion. However, there was a significant decrease in the resting LDF baseline during superfusion of the cranial window with 10 μM nitrite to 72% of the ACSF baseline (Fig. 2C, P < 0.05), suggesting this dose caused non-specific effects.

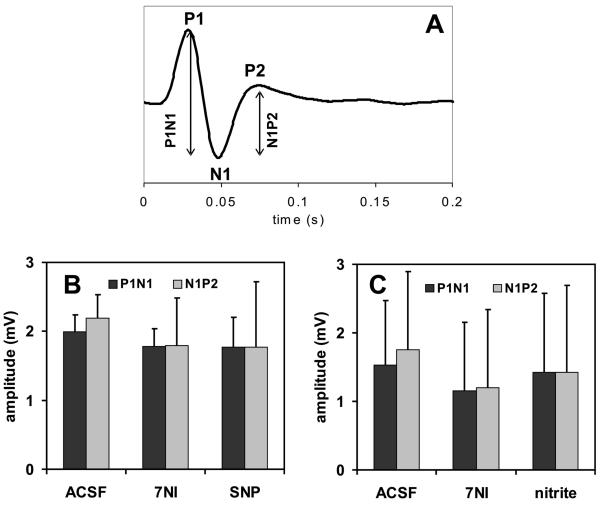

2.3. Somatosensory evoked potentials (SEP)

To ensure that the pharmacological treatments caused specific effects on the CBF only and not on the neural activity, somatosensory evoked potentials (SEP) were measured. Figure 3 shows the amplitude of the SEP recorded in response to forepaw stimulation during the different pharmacological conditions. There were no significant changes to the amplitude of the SEP at any of the pharmacological conditions, suggesting no effect of either 7NI, SNP or nitrite on the local neuronal activity.

Figure 3.

(A) Typical somatosensory evoked potential recorded during forepaw stimulation showing the usual P1, N1 and P2 peaks and their relative amplitudes. SEP amplitudes did not change during the different pharmacological conditions, neither during administration of SNP (B) nor nitrite (C).

3. Discussion

In the present study, we used a well-established rat model of somatosensory stimulation to investigate the hypothesis that nitrite can serve as an alternative source of NO to sustain the hemodynamic response to functional brain stimulation. We used pharmacological manipulations to inhibit the functional synthesis of NO in the brain, followed by exogenous delivery of NO compounds, and we performed LDF experiments to investigate the role of NO in neurovascular coupling. We showed that preferential inhibition of the neuronal isoform of nitric oxide synthase, nNOS, produces a robust decline in the LDF-measured CBF response to forepaw stimulation, and that administration of the NO precursor nitrite, as well as of the NO donor sodium nitroprusside, at doses that do not cause a change in the resting CBF baseline, can significantly recover the attenuation caused by nNOS inhibition. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to show that the brain can use nitrite as a direct functional source of NO. Our data also suggests the existence of a fast mechanism to convert nitrite to NO.

3.1.Nitrite as a Physiological Source of NO in Vivo

The main finding of the present study is that brain tissue is able to obtain necessary NO from sources other than enzymatic NOS activity. We showed that nitrite is an alternative source of NO in brain tissue. Nitrite has gained significant relevance to treat hypertension and other disorders associated with NO impairments (van Faassen et al., 2009). The amount of nitrite in blood is highly dependent on diet. In humans the normal range is 150-300 nM (Dejam et al., 2005), similar to values reported in rats (Kleinbongard et al., 2003). The amount of nitrite content in tissues can be even higher - closer to the micromolar range (Samouilov et al., 2007). We tested three nitrite concentrations – 0.1 μM, 1 μM and 10 μM – to cover a wide range. We observed minimal effects of the 0.1 μM on the functional CBF response, but we observed a full recovery of the CBF response with the 1 μM dose, suggesting that this is the concentration necessary to achieve functional equivalence with NO synthesis. Indeed, when we tested the concentration of 10 μM, we observed a significantly lower recovery of the functional CBF response that was accompanied by non-specific changes in the resting CBF baseline.

One difficulty associated with the effective delivery of nitrite to the brain relates to the systemic effects caused by large doses. Intravenous infusion of nitrite at a concentration of 200 μM was previously shown to cause global vasodilatation in the brain (Rifkind et al., 2007), which will likely interfere with neurovascular coupling. On the other hand, while effective, the direct delivery of nitrite to the brain achieved here via superfusion over the cranial window is invasive and not suitable for clinical purposes. Recently, increased blood nitrite levels achieved by intake of high-nitrate diet have been shown to improve regional brain perfusion in elderly volunteers (Presley et al., 2011), suggesting a viable way to manipulate endogenous nitrite levels. Further studies are necessary to optimize the dose and route of delivery of nitrite to the brain.

3.2. General mechanisms of nitrite reduction to NO in the brain

There are several known mechanisms explaining how nitrite can be converted to NO (for a recent review see (van Faassen et al., 2009)). The oldest mechanism recognized in humans relates to the hypoxia-driven nitrite reductase activity of deoxyhemoglobin (Cosby et al., 2003). However, it is unlikely that this is the dominant mechanism for neurovascular coupling, as this reaction happens inside red blood cells (RBC) with a half-life of a few minutes, much longer than the typical transit-time of RBC across the capillary network (circa 0.5s, (Hutchinson et al., 2006)). Other mechanisms relate to the use of nitrite as an alternative substrate by several enzymes present in brain tissue – NOS, XO and AO – under hypoxic/acidic conditions (Li et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009; Mikula et al., 2009). However, while these enzymes can promote the local production of NO from nitrite, their reactions are also rather slow and run preferentially at unphysiologically low levels of brain oxygen.

Recently, the nitrite anhydrase activity of carbonic anhydrase (CA) in RBC was described (Aamand et al., 2009). CA is present in all tissues, including the brain, and it one of the fastest acting enzymes - its reaction with CO2 is limited mainly by diffusion. Since nitrite does not bind to the enzyme active Zn site, where the CO2 hydration takes place, it does not compete with CO2 for the active site and does not interfere with the main role of CA in regulating pH. Further experiments are warranted to investigate the physiological relevance of CA in producing NO from nitrite.

Another exciting mechanism relates to the direct non-enzymatic conversion of nitrite to NO by acidic disproportionation. An elegant and simple model coupling the conversion of nitrite into NO by ascorbic/dehydroascorbic acid released from neurons during increased neuronal activity was proposed by Millar (Millar, 1995). The brain is the organ in the body with the highest concentration of ascorbic acid (up to 10mM), which is actively uptaken by neurons (Harrison and May, 2009). According to the Millar model, ascorbate is released during neuronal activity into the extracellular fluid, where it reacts with extracellular nitrite to generate NO. It will be interesting to test the physiological relevance of this mechanism in the near future.

4. Experimental Procedures

4.1. Animal preparation

All animal procedures were performed in according to the guidelines of the NINDS/NIDCD Animal Care and Use Committee under the approved animal study proposal 1198-08. Male (n = 24) Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Frederick, MD) weighting 317 ± 58 g were tracheostomized and mechanically ventilated with a mixture of oxygen-enriched air and isoflurane (5% induction followed by 2% maintenance). The right femoral artery and vein were cannulated using PE-50 catheters for arterial blood pressure registration and blood gas analysis, and for intravenous administration of drugs, respectively. A small cranial window (~5 mm in diameter) was placed over the forelimb area of right primary somatosensory cortex (S1FL, bregma 0 mm, 3.5 mm lateral) and equipped with three PE-10 tubes for delivery and drainage of the solutions containing pharmacological agents (local superfusion) and positioning of the active electrode for the registration of SEP. Standard #1 microscope slides coverslips were secured with dental acrylic to cover the cranial windows.

After all necessary surgical procedures were completed, isoflurane was discontinued and anesthesia was switched to intravenous α-chloralose (80 mg/kg initial bolus followed by 27 mg/kg/h constant infusion). Pancuronium bromide was given together with the α-chloralose solution at a dose of 1 mg/kg/h.

4.2. Physiological monitoring

Rectal temperature was monitored and maintained at 37 ± 0.4°C using a heating blanket (CWE Inc., Ardmore, PA, USA). Tidal pressure of ventilation (SAR 830/P, CWE inc., Colorado Springs, CO), mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), and heart rate were monitored and recorded using a pressure transducer connected to BIOPAC MP system (Biopac Systems Inc., Goleta, CA). Arterial blood gases - pO2, pCO2, pH and electrolytes - were periodically checked using a blood gas analyzer (ABL77, Radiometer America, Inc., Westlake, OH) and kept within their normal physiological range - see Table 1 for values.

4.3. Somatosensory Stimulation

Two needle electrodes were inserted under the skin of the left forepaw (in the space between digits 2 and 3, and 4 and 5). Electrical stimulation was accomplished by the delivery of 0.3 ms, 2 mA pulses, played out at a frequency of 3 Hz. These parameters were chosen because they have been previously shown to elicit the largest CBF responses (Silva et al., 1999).

4.4. Pharmacological manipulation - nNOS inhibition, SNP and nitrite administration

First, baseline LDF parameters were recorded for 20 min with continuous superfusion of the cranial window with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) at the same rate as used to deliver NO compounds – 10 μl/min. Then, nNOS was inhibited by an IP injection of selective nNOS inhibitor 7NI (50 mg/kg, dissolved in a 1:9 solution of DMSO:peanut oil), and LDF parameters were continuously recorded. Usually, inhibition occurred within 10 min after injection, full effect was observed in 15-20 min and persisted for at least 1.5 hour as determined in LDF control experiments (n = 2, results not shown). ACSF was continuously delivered during this phase as described above.

Finally, SNP (n = 9) or nitrite (n = 13) was applied topically to the somatosensory cortex via superfusion of the cranial window. SNP was delivered at 10 nM, while nitrite was tested at 0.1 μM, 1 μM and 10 μM.

4.5.Laser Doppler Flowmetry

CBF was measured through the cranial window using a laser-Doppler flowmeter (MoorLab, Moor Instruments Ltd., Millwey, UK) with an 800 μm diameter needle-shaped probe mounted on a micromanipulator and positioned over the right S1FL in areas free of large vessels. The CBF flux and concentration parameters of the LDF instrument were acquired with a sampling rate of 40 Hz, and a moving average constant of 3 samples, and recorded with the BIOPAC system for further analysis. The functional paradigm comprised 7 epochs, each consisting of a 10s-long pre-stimulus baseline, followed by a 5s-long stimulation period, and finalized with a 30s-long return to baseline. The 7 epochs were presented consecutively for a total data acquisition time of 5 min 15 s per paradigm presentation. Each paradigm was presented 4 times during baseline (ACSF superfusion), 7 times after the IP injection of 7NI, and 9 times following superfusion with SNP or nitrite.

4.6. Electrophysiology Experiments

To record the SEPs with maximal sensitivity and specificity but without compromising the cerebral vasculature, a 100 μm diameter stainless-steel tripolar electrode with impedance of 1.1MΩ at the sampling frequency of 2.5 kHz (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) were placed over the left and right S1FL regions and into the midline of cerebellum (reference electrode). Using a BIOPAC MP system (Biopac Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA), the SEPs were amplified 20,000-fold, bandpass filtered between 0.5 and 500 Hz, digitized at a sampling rate of 2.5 kHz, and transferred to a computer.

4.7. Data analysis

For each epoch within a stimulus paradigm, the LDF time-courses were expressed as percent changes from the mean pre-stimulus baseline (see Fig. 1) and averaged across all seven stimulation epochs. CBF responses were calculated as the area under the functional CBF (fCBF) response (Bakalova et al., 2001). Values for fCBF inhibition by 7NI were taken as the mean value of the LDF data 20-35min after the injection of the nNOS inhibitor, while values following SNP or nitrite administration were determined from the mean value of the LDF data recorded 25-45 min following superfusion of the compounds.

SEP were averaged across all seven stimulation epochs in each run. The SEP peak amplitude, measured as the amplitude difference between the N1 and the P2 peaks, and the SEP latency, measured as the time interval from stimulus application to the time to the P1 peak, were computed from the averaged SEP trace and compared across different pharmacological conditions.

Data in graphs and tables are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using paired Student’s t-test to compare CBF and SEP responses after vehicle or drug superfusions, and one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Newman–Keuls comparison test for comparing combined groups. The significance threshold was set at p<0.05.

4.8. Materials

Nitrite, SNP, 7NItro-indazole (7NI), α-chloralose, dimethyl-sulfoxide (DMSO) and peanut oil were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), pancuronium bromide from Sicor Pharmaceutical (Irvine, CA), heparin from APP Pharmaceutical LLC (Schaumburg, IL) and Florane (isoflurane) from Baxter (Deerfield, IL).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we showed that administration of the NO precursor nitrite, at doses that do not cause a change in the resting CBF baseline, can significantly recover the attenuation of the CBF response to somatosensory stimulation in the α-chloralose anesthetized rat model. Our study shows that nitrite can serve as a direct physiological source of NO. Future experiments will focus on identifying the specific mechanisms of NO production from nitrite in the brain.

Highlights.

This study investigates the role of nitrite in neurovascular coupling

Nitrite efficiently recovers the CBF response to increased neural activity

Nitrite can be a physiological source of NO in neurovascular coupling physiology

6. Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Xianfeng (Lisa) Zhang for her excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- 7NI

7NItro-indazole

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- AO

aldehyde oxidase

- CA

carbonic anhydrase

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- fCBF

functional cerebral blood flow

- LDF

laser Doppler flowmetry

- MABP

mean arterial blood pressure

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NO

nitric oxide

- S1FL

forelimb area of primary somatosensory cortex

- SEP

somatosensory evoked potentials

- sGC

soluble guanylyl cyclase

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

- XO

xanthine oxidase

Footnotes

Disclosure: Alan N. Schechter, MD is a coauthor of the US patent for nitrite use in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

7. References

- Aamand R, Dalsgaard T, Jensen FB, Simonsen U, Roepstorff A, Fago A. Generation of nitric oxide from nitrite by carbonic anhydrase: a possible link between metabolic activity and vasodilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H2068–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00525.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Buchan AM, Charpak S, Lauritzen M, Macvicar BA, Newman EA. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature. 2010;468:232–43. doi: 10.1038/nature09613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakalova R, Matsuura T, Kanno I. Frequency dependence of local cerebral blood flow induced by somatosensory hind paw stimulation in rat under normo- and hypercapnia. Jpn J Physiol. 2001;51:201–8. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.51.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauli B, Hamel E. Revisiting the role of neurons in neurovascular coupling. Front Neuroenergetics. 2010;2:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fnene.2010.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholet N, Seylaz J, Lacombe P, Bonvento G. Local uncoupling of the cerebrovascular and metabolic responses to somatosensory stimulation after neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibition. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:1191–201. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199711000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosby K, Partovi KS, Crawford JH, Patel RP, Reiter CD, Martyr S, Yang BK, Waclawiw MA, Zalos G, Xu X, Huang KT, Shields H, Kim-Shapiro DB, Schechter AN, Cannon RO, 3rd, Gladwin MT. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1498–505. doi: 10.1038/nm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejam A, Hunter CJ, Pelletier MM, Hsu LL, Machado RF, Shiva S, Power GG, Kelm M, Gladwin MT, Schechter AN. Erythrocytes are the major intravascular storage sites of nitrite in human blood. Blood. 2005;106:734–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, Iadecola C. The role of neuronal signaling in controlling cerebral blood flow. Brain Lang. 2007;102:141–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feelisch M, Fernandez BO, Bryan NS, Garcia-Saura MF, Bauer S, Whitlock DR, Ford PC, Janero DR, Rodriguez J, Ashrafian H. Tissue processing of nitrite in hypoxia: an intricate interplay of nitric oxide-generating and - scavenging systems. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33927–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806654200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garthwaite J. Concepts of neural nitric oxide-mediated transmission. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2783–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girouard H, Iadecola C. Neurovascular coupling in the normal brain and in hypertension, stroke, and Alzheimer disease. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:328–35. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00966.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton NB, Attwell D, Hall CN. Pericyte-mediated regulation of capillary diameter: a component of neurovascular coupling in health and disease. Front Neuroenergetics. 2010;2 doi: 10.3389/fnene.2010.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison FE, May JM. Vitamin C function in the brain: vital role of the ascorbate transporter SVCT2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:719–30. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson EB, Stefanovic B, Koretsky AP, Silva AC. Spatial flow-volume dissociation of the cerebral microcirculatory response to mild hypercapnia. Neuroimage. 2006;32:520–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C. Regulation of the cerebral microcirculation during neural activity: is nitric oxide the missing link? Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:206–14. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90156-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:347–60. doi: 10.1038/nrn1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbongard P, Dejam A, Lauer T, Rassaf T, Schindler A, Picker O, Scheeren T, Godecke A, Schrader J, Schulz R, Heusch G, Schaub GA, Bryan NS, Feelisch M, Kelm M. Plasma nitrite reflects constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity in mammals. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:790–6. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Cui H, Kundu TK, Alzawahra W, Zweier JL. Nitric oxide production from nitrite occurs primarily in tissues not in the blood: critical role of xanthine oxidase and aldehyde oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17855–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801785200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Kundu TK, Zweier JL. Characterization of the magnitude and mechanism of aldehyde oxidase-mediated nitric oxide production from nitrite. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33850–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindauer U, Megow D, Matsuda H, Dirnagl U. Nitric oxide: a modulator, but not a mediator, of neurovascular coupling in rat somatosensory cortex. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H799–811. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikula I, Durocher S, Martasek P, Mutus B, Slama-Schwok A. Isoform-specific differences in the nitrite reductase activity of nitric oxide synthases under hypoxia. Biochem J. 2009;418:673–82. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar J. The nitric oxide/ascorbate cycle: how neurones may control their own oxygen supply. Med Hypotheses. 1995;45:21–6. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(95)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presley TD, Morgan AR, Bechtold E, Clodfelter W, Dove RW, Jennings JM, Kraft RA, King SB, Laurienti PJ, Rejeski WJ, Burdette JH, Kim-Shapiro DB, Miller GD. Acute effect of a high nitrate diet on brain perfusion in older adults. Nitric Oxide. 2011;24:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkind JM, Nagababu E, Barbiro-Michaely E, Ramasamy S, Pluta RM, Mayevsky A. Nitrite infusion increases cerebral blood flow and decreases mean arterial blood pressure in rats: a role for red cell NO. Nitric Oxide. 2007;16:448–56. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samouilov A, Li H, Zweier JL. Nitrite as NO donor in cells and tissues. In: van Faassen E, Vanin AF, editors. Radicals for Life: The various forms of nitric oxide. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2007. pp. 313–336. [Google Scholar]

- Silva AC, Lee SP, Yang G, Iadecola C, Kim SG. Simultaneous blood oxygenation level-dependent and cerebral blood flow functional magnetic resonance imaging during forepaw stimulation in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:871–9. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199908000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanovic B, Schwindt W, Hoehn M, Silva AC. Functional uncoupling of hemodynamic from neuronal response by inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:741–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda N, Okamura T. The pharmacology of nitric oxide in the peripheral nervous system of blood vessels. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:271–324. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda N, Ayajiki K, Okamura T. Cerebral blood flow regulation by nitric oxide: recent advances. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:62–97. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Faassen EE, Bahrami S, Feelisch M, Hogg N, Kelm M, Kim-Shapiro DB, Kozlov AV, Li H, Lundberg JO, Mason R, Nohl H, Rassaf T, Samouilov A, Slama-Schwok A, Shiva S, Vanin AF, Weitzberg E, Zweier J, Gladwin MT. Nitrite as regulator of hypoxic signaling in mammalian physiology. Med Res Rev. 2009;29:683–741. doi: 10.1002/med.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Iadecola C. Obligatory role of NO in glutamate-dependent hyperemia evoked from cerebellar parallel fibers. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R1155–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.4.R1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]