Abstract

Objective

To validate accelerometry based on its correlations with 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and oxygen cost of walking as objective markers of walking limitations in multiple sclerosis (MS).

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

Laboratory and general community.

Participants

Ambulatory participants with MS (N=26) who resided in the local community.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures

Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) scale and Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale-12 (MSWS-12); 6-minute walk test while wearing a portable metabolic unit for measuring the 6MWD and oxygen cost of walking; accelerometer during the waking hours of a 7-day period.

Results

The average of total daily movement counts from the accelerometer correlated significantly and strongly with MSWS-12 scores (ρ−.681, P=.001), PDDS scores (ρ−.609, P=.001), 6MWD (ρ.519, P=.003), and oxygen cost of walking (ρ−.541, P=.002).

Conclusions

We provide evidence that further supports the validity of accelerometry as a measure of walking limitations in ambulatory persons with MS.

Keywords: Gait, Mobility limitation, Multiple sclerosis, Rehabilitation, Walking

Walking limitations are a highly prevalent feature of MS that result in the indelible loss of independence and quality of life. Indeed, nearly 75% of persons with MS report some degree of ambulatory limitations and disability,1 and restrictions with walking have been identified as a major physical problem that restricts physical functioning and independence during activities of daily life.1 Consequently, there has been a growing interest in the measurement of walking limitations in the context of everyday life. This is essential for the evaluation of disability and disease progression, as well as the efficacy of disease-modifying drugs, symptomatic agents, and rehabilitation strategies in persons with MS.

Accelerometers have been identified as a criterion standard for measuring ambulatory mobility in neurologic disorders because such a device captures total ambulatory activity undertaken during the usual range of daily activities in a person’s typical or customary environment.2 Accelerometers have historically been applied to the study of physical activity behavior (ie, bodily movement produced by contraction of skeletal muscles that results in a substantial increase in energy expenditure),3 but there is emerging recognition of the potential value for measuring walking limitations in neurologic conditions2 including MS.4,5 Commercially available accelerometers are typically worn around the waist (ie, center of mass) and capture the vertical displacement of the body during movements such as walking. This is not that same as a pedometer that only captures steps or strides, but rather the accelerometer captures the frequency and intensity of movement in terms of movement or displacement counts over a continuous time interval. Importantly, walking is assumed to be a primary and significant form of movement undertaken by ambulatory persons with MS. Accordingly, the characteristics of gait (eg, speed, stride length and cadence, and double-support time) and the intensity, duration, and frequency of a person’s walking will affect the signal captured by the accelerometer. By this reasoning, accelerometers have the potential to provide an objective measurement of walking limitations that takes place within the context of real life.

An emerging body of research has examined the association between accelerometer output and patient-rated measures of walking limitations in persons with MS. The average of total daily movement counts across a 7-day period recorded from a uniaxial accelerometer worn around the waist has correlated with scores from the MSWS-12 (r=−.64),6 self-reported EDSS (r=−.60),7 mobility subscale of the PS (r=−.60),8 and Symptom Inventory (r=−.56).8 One recent study4 indicated that the average of total daily movement counts across a 7-day period recorded from the aforementioned accelerometer worn around the waist correlated strongly with scores from self-reported measures of walking limitations (eg, MSWS-12, r=−.70; mobility subscale of PS, r=−.68) and physical activity (Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire, r=.64; Short-Form International Physical Activity Questionnaire, r=.56) in persons with MS. Importantly, the correlations were stronger with scores from self-reported measures of walking limitations (eg, MSWS-12, r=−.45; mobility subscale of PS, r=−.56) than physical activity (Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire, r=.38; Short-Form International Physical Activity Questionnaire, r=.34) within the subsample who had ambulatory limitations.4

The existing evidence for the validity of accelerometry as a measure of walking limitations in MS is promising, but needs to be further strengthened by assessing its association with objective markers of ambulatory limitations such as the 6MWD and oxygen cost of walking. The 6MWT was originally developed as a measure of walking endurance capacity in persons with stable chronic airflow obstruction,9 and has been identified as a possible measure of mobility disability in persons with MS.10 The distance traveled during the 6MWT has consistently differed between persons with MS and controls and has correlated with EDSS, timed 25-foot walk, and MSWS-12 scores in persons with MS.10–12 The oxygen cost of walking is a physiologic marker that captures the interaction between walking distance/speed and energy expenditure. This physiologic marker measures energy expenditure per unit traveled (ie, milliliters of oxygen consumed per kilogram of body weight per meter traveled, or mL·kg−1·m−1, or oxygen consumption per unit walking speed) and is influenced by subclinical and clinical manifestations of pathologic gait abnormalities.13 There is evidence that the oxygen cost of walking is affected by the degree of locomotor limitations in persons with neurologic and orthopedic conditions,13,14 and is elevated in persons with MS who have moderate disability compared with controls.15

There is value in assessing the associations among accelerometry, 6MWD, and oxygen cost of walking. This value is, in part, based on overcoming a major limitation of previous work validating accelerometry, namely, the reliance on patient-rated measures of perceived walking limitations that can be influenced by the accuracy of recall and self-reporting biases. By comparison, the 6MWD measures endurance walking capacity and the oxygen cost of walking measures the efficiency of walking, both in the context of a limited time frame in an artificial setting. Logically, persons who have reduced endurance capacity and efficiency for walking should, in turn, have a lower capacity for ambulation in real life, and this should be reflected by a lower average of total daily movement counts recorded by the accelerometer. This would essentially link together measures of capacity for walking in a given context and moment with actual walking performance in the real world, and extend previous research on the association between perceptions of walking limitations and actual walking behavior. This assessment would have further value by examining the degree of the associations between laboratory- versus home-based measurements and long- versus short-duration tests. For example, if the laboratory-based and short-duration 6MWD correlates strongly with the accelerometer that is home based and recorded over a long duration, this might have implications for the selection of the measures in subsequent clinical trials and practice with persons who have MS.

Validation of an outcome is an ongoing and evolving process,16 and we sought to further validate accelerometry as a measure of walking limitations in persons with MS. Accordingly, this study replicated previous research by examining the association between accelerometry and self-report measures of walking limitations (MSWS-12 and PDDS scale), and extended previous research by examining the association between accelerometry and objective markers of mobility limitations (ie, 6MWD and oxygen cost of walking) in persons with MS. We expected that the average of total daily movement counts from the accelerometer would demonstrate strong correlations with MSWS-12 scores, PDDS scores, 6MWD, and oxygen cost of walking.

METHODS

Participants With MS

We recruited a sample of persons with MS through distribution of advertisements among 3 sources: a pool of previous research participants with MS, the local MS chapter, and referrals from local neurologists. Participants with MS who were interested in the study contacted our laboratory, by telephone or e-mail, for further information about the study. The study was described as a focus on the measurement of walking and energy expenditure among people with MS, and if the participant was interested, this was followed by a screening for inclusion criteria and a confirmed diagnosis of MS. The following inclusion criteria were applied: relapse free during the previous 30 days; independent ambulation or ambulation with single-point assistance (ie, cane or crutch); age between 18 and 64 years; and absence of risk factors for undertaking strenuous physical activity (eg, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension). Fifty people with MS underwent screening; 26 satisfied inclusion criteria and volunteered for participation.

Measures

This study included 6 ActiGraph model 7164 accelerometers.a All units were initially calibrated by the manufacturer, and furthermore, there was less than 10% variation among the accelerometers in output based on our internal assessment using a 15-minute period of walking on a treadmill by a member of the research team. This unit is small (2.0×1.6×0.6in), lightweight (1.5oz), and contains a single, vertical axis piezoelectric bender element. The bender element has a detection range between 0.05 and −3.2 gravities, and generates an electrical signal proportionate to the force acting on it during bodily movement (ie, not a pedometer). The electrical signal is band-pass filtered (.25–2.5Hz), digitized by an analog-to-digital converter, numerically integrated over a sampling interval (eg, 1-minute epoch), and stored in random access memory as movement counts. The movement counts represent a summation of the positive and negative accelerations over a sampling interval, thereby providing a quantitative measure of the participant’s movement (ie, displacement of the center of mass during movement). This accelerometer can be used for prolonged periods (ie, days, weeks, and months), with minimal interference on normal patterns of life, and the signal can be inspected for compliance. The accelerometers were programmed for epoch length (1min in this study) and start time (12:01 AM in this study). The accelerometers were worn on a belt around the waist during the waking hours of a 7-day period, except while bathing, showering, or swimming. Data were retrieved for analysis via a personal computer reader interface unit and software provided with the ActiGraph accelerometers. The downloaded data were entered into Microsoft Excel,b and the average of total daily movement counts (ie, unit of analysis) was computed as the sum of movement counts across an entire day and then averaged across the 7-day period. There is no upper boundary for the average of total daily movement counts, and lower values reflect less ambulatory activity (ie, great limitations in walking). We inspected the minute-by-minute accelerometer data for long periods of continuous zeros as a check of compliance with wearing the device, and used a criterion of 60 minutes of continuous zeros for noncompliance. We based the judgment of a valid day of measurement on a minimum of 10 hours of total wear time. We considered the data to be spurious when counts exceeded 20,000 per minute, and we required that participants have 7 valid days of data for a reliable estimate (intraclass correlation coefficient, .89). All participants satisfied those criteria and were included in the data analyses.

Self-reported walking ability was measured using the MSWS-12.1,17 The 12 items on the MSWS-12 are rated on a scale ranging between 1 (not at all) and 5 (extremely). The total MSWS-12 score ranges between 0 and 100, and is computed by subtracting the minimum possible score (12), dividing by the maximal score (60), and multiplying by 100, with higher scores reflecting greater perceived walking limitations.1,17 Coefficient α for the MSWS-12 in this study was .96. Mobility disability was further measured with the PDDS scale.18 This self-report scale was developed as an inexpensive surrogate for the EDSS, and scores from the PDDS scale are linearly and strongly related to physician-administered EDSS scores (r=.93).18 PDDS scores range between 0 and 8, with higher scores reflecting greater perceived mobility disability.18

The 6MWT was performed in a handicap-accessible rectangular hallway that was clear of obstructions and foot traffic, and involved the participant’s comfortable walking speed. Two researchers followed the participant during the 6MWT; one pushed a measuring wheelc outfitted with a calibrated bicycle computer,d and the other recorded the speed and distance. We reminded the participant before and during the 6MWT to select and maintain a comfortable walking pace and disregard the researcher’s presence. A lower 6MWD reflects a reduced endurance walking capacity.10 Oxygen consumption was measured during the last 3 minutes of the 6MWT (ie, steady-state oxygen consumption) by using a commercially available portable metabolic unit,e and the flowmeter and oxygen and carbon dioxide sensors of the portable metabolic unit were calibrated before each testing session. The oxygen cost of walking was expressed as milliliters per kilogram per meter (mL·kg−1·m−1) by dividing oxygen consumption in milliliters per kilogram per minute (mL·kg−1·m−1) by walking speed in meters per minute (m/min). A higher oxygen cost of walking reflects a lower efficiency of walking.13

Procedure

The procedure was approved by an institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent documentation. The participants completed a demographic questionnaire, PDDS, and MSWS-12, and then were measured for weight and height on a scale-stadiometer unit.f The participants along with 1 researcher walked the course for the 6MWT as a familiarization protocol. We then connected the portable metabolic unit along with the associated face mask for collecting expired gases, and the participants sat and rested quietly for 5 minutes. This was followed by the 6MWT. The participant then received an accelerometer along with instructions and a log, and wore the device during the waking hours, except while bathing, showering, or swimming, across the subsequent 7-day period. The actual wear time was recorded in a log, but we did not ask that participants maintain a diary of activities. We did not remind the participants to wear the units across the 7-day period because, based on our experiences, people who receive the devices, instructions, and logs in person typically comply with instructions for proper usage. The device was then returned through the United States Postal Service. Participants received $20 remuneration for undertaking the study.

Data Analysis

We initially computed descriptive (ie, mean, SD, and range) and distributional (ie, skewness and kurtosis along with SEs) statistics. The associations between scores from the accelerometer and MSWS-12, PDDS, 6MWD, and oxygen cost of walking were estimated using Spearman ρ rank-order correlations. This nonparametric approach was selected, given the relatively small sample size and deviation from an approximate normal distribution based on skewness and kurtosis estimates for some variables. Cohen’s guidelines of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 were used for judging the magnitude of the correlation coefficients as small, moderate, and large, respectively.19

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The mean age ± SD of the sample was 43.1±11.9 years, and the sample was primarily women (n=22, 85%) and white (n=22, 85%). The mean height ± SD and mean weight ± SD were 169.2±9.3cm and 70.2±14.7kg, respectively, and this yielded a mean body mass index ± SD of 24.6±5.3kg/m2. The mean time ± SD since MS diagnosis was 11.6±8.4 years, and all participants had relapsing-remitting MS.

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive and distributional statistics for the accelerometer, MSWS-12, PDDS, 6MWD, and oxygen cost of walking are provided in table 1. There was significant skewness in the accelerometer data, and skewness and kurtosis in the 6MWD and oxygen cost of walking data. The mean accelerometer count ± SD in the present study was 212,749±101,823, and this was consistent with the mean value (194,940±107,822) from previous research that included persons with MS.6 Other research has indicated that samples without and with ambulatory limitations have mean accelerometer counts ± SD of 243,635±113,866 and 128,501± 60,480, respectively.4 The mean score ± SD for the MSWS-12 in the present study of 24.4±19.2 was consistent with that reported for a sample without ambulatory limitations (23.2±19.0), but not with that reported for a sample with ambulatory limitations (55.9±17.9).4 The mean PDDS scale score for the participants was 1.8 (range, 0–5), and this corresponds with a moderate disability level, whereas the upper-end PDDS score of 5 corresponds with a disability level of late cane.18 The mean 6MWD ± SD in the present study of 1419±400ft was consistent with the 6MWD (1662±338ft) found in previous research for those who had moderate MS, but not for those with mild and severe MS (1978±159 and 1277±255ft, respectively).10 The mean ± SD oxygen cost of walking in the present study of .19±.09 mL·kg−1·m−1 was consistent with that of previous research on persons with MS (.17±.03 mL·kg−1·m−1).14 The sample of persons in the present study would be characterized as having mild to moderate MS and intact ambulatory ability.

Table 1.

Descriptive and Distributional Statistics for the Measures in a Sample of 26 Persons With MS

| Measure | Mean ± SD | Range of Scores | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerometer (counts/d) | 212,749±101,823 | 68,653–467,039 | 1.08 | 1.04 |

| MSWS-12 | 24.4±19.2 | 0–58 | 0.28 | −1.12 |

| PDDS scale | 1.8±1.6 | 0–5 | 0.21 | −1.37 |

| 6MWD (ft) | 1419±400 | 327–2070 | −1.27 | 2.72 |

| O2 cost of walking (mL·kg−1·m−1) | .19±.09 | .13–.55 | 3.25 | 11.95 |

NOTE. SEs of skewness or kurtosis estimates are .46 and .89, respectively, and values of skewness or kurtosis divided by the respective SE that exceed 1.96 suggest a departure from a normal distribution.

Abbreviation: O2, oxygen.

Bivariate Correlation Analysis

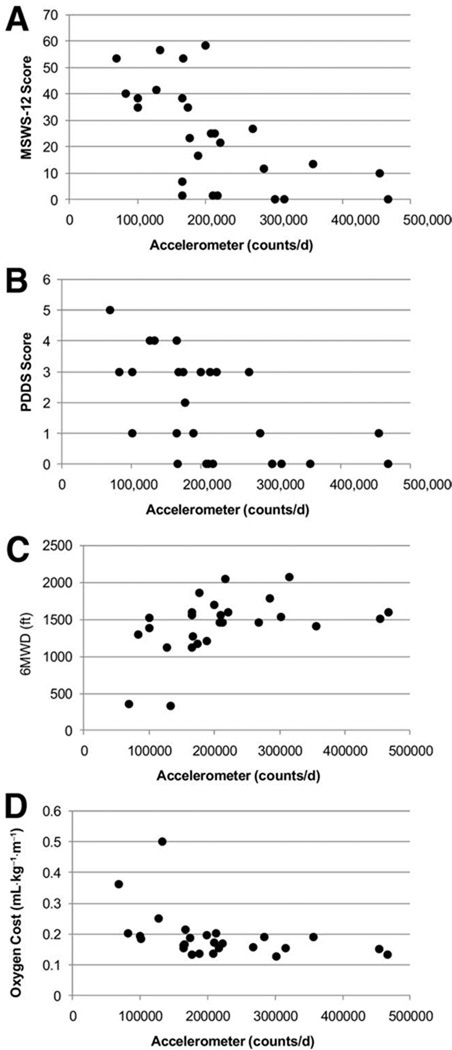

Table 2 presents a matrix of correlations among scores from the accelerometer, MSWS-12 scores, PDDS, 6MWT, and oxygen cost of walking. Scatterplots of the associations are provided in figure 1. The average of total daily movement counts from the accelerometer correlated significantly and strongly with MSWS-12 (ρ=−.681, P=.0001), PDDS scores (ρ=−.609, P=.001), 6MWD (ρ=.519, P=.007), and oxygen cost of walking (ρ=−.541, P=.004). Other noteworthy correlations were observed between MSWS-12 and PDDS scores (ρ=.847, P=.0001), MSWS-12 scores and oxygen cost of walking (ρ=.740, P=.0001), and PDDS scores and oxygen cost of walking (ρ=.668, P=.0001).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Among Scores From the Measures in a Sample of 26 Persons With MS

| Measure | Accelerometer | MSWS-12 | PDDS | 6MWD | O2 Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerometer (counts/d) | — | ||||

| MSWS-12 | −.681 | — | |||

| PDDS scale | −.609 | .847 | — | ||

| 6MWD (ft) | .519 | −.534 | −.427 | — | |

| O2 cost of walking (mL·kg−1·m−1) | −.541 | .740 | .668 | −.515 | — |

NOTE. All correlations are statistically significant (P<.05).

Abbreviation: O2, oxygen.

Fig 1.

Scatterplots of the associations between accelerometer counts per day and MSWS-12 scores (A), PDDS scores (B), 6MWD (C), and oxygen cost of walking (D) in a sample of 26 persons with MS.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study indicate that the average of total daily movement counts from the accelerometer was significantly and strongly correlated with distance traveled and the oxygen cost of walking during the 6MWT. This observation is important because the 6MWD and oxygen cost of walking are objective, laboratory-based markers of locomotor limitations in MS that likely reflect the capacity for ambulation in real life. Persons who have a lower capacity for walking based on a reduced 6MWD and an elevated oxygen cost of walking should, in turn, have a lower average of total daily movement counts across a 7-day period as recorded by the accelerometer. Our results are largely consistent with this argument and indicate that accelerometry is, in part, likely reflecting the reduced capacity for ambulation among persons with MS that manifests in everyday life. Such an observation further supports the validity of accelerometry as an objective marker of walking limitations in real life among ambulatory persons with MS. An alternative interpretation, nevertheless, is that our results provide evidence for the application of the 6MWD as a valid outcome for walking limitations in MS. This measure is simple, rapid, and easy to administer, and might be less onerous for participants and less frustrating for researchers than accelerometry, particularly under conditions of lost data, low compliance, and a longer 7-day period of monitoring.

To our knowledge, previous validation studies have primarily focused on the pattern of correlations between the average of total daily movement counts from an ActiGraph model 7164 accelerometer and scores from self-reported instruments such as the MSWS-12, EDSS, mobility subscale of the PS, and Symptom Inventory.4–8 For example, 2 studies reported correlation coefficients between average of total daily movement counts from the accelerometer and MSWS-12 scores of r=−.647 and r=–.70,4 and 1 study reported a correlation between the average of total daily movement counts from the accelerometer and self-reported EDSS scores of r=−.60.7 We reported correlation coefficients of ρ=–.68 and ρ=–.61 for the associations between the average of total daily movement counts from the accelerometer and MSWS-12 and PDDS scores, respectively, in the present study. This consistency in correlations across studies further supports the observation that accelerometry is a marker of walking limitations in MS. The generally strong correlations among accelerometry, 6MWD, oxygen cost of walking, MSWS-12, and PDDS demonstrate that all 5 measures are capturing a common element of walking limitations. Importantly, the correlations did not approximate unity (ie, r=1.00), and this might reflect unaccounted-for factors that affect the amount of walking captured by the accelerometer in everyday life, such as inclement weather, vacations, and nonrepresentative, sedentary weeks of monitoring. We further note that the accelerometer may be providing information that is beyond the overlap or commonality with these other measures (eg, physical activity),4,5 and studies in larger, more disabled MS populations are needed to begin to parse out such possibilities.

Additional research is needed that continues to enhance our understanding of accelerometer output and the application of accelerometers in clinical research and care. The most pressing research effort is a comparative evaluation of accelerometry, MSWS-12 and PDDS scores, the oxygen cost of walking, and 6MWD in response to drug (eg, intravenous corticosteroid treatment or sustained-release dalfampridine) or rehabilitation (eg, physical therapy or occupational therapy) interventions that use a randomized controlled trial design. Such an inquiry would establish the relative responsiveness of those measures for capturing clinically meaningful improvement in walking in persons with MS. Research that examines and identifies such comparative responsiveness might allow for better design of therapeutic interventions based on accelerometry or the other markers as outcomes. Such a study would further clarify, under criterion standard conditions of a randomized controlled trial design, that scores or units from the markers validly reflect true and meaningful differences and changes in walking mobility in MS. This design will parse out the clinical meaning of the measures for capturing walking limitations and their change over time.

Study Limitations

This study is not without limitations. Perhaps the greatest limitation is that participants did not maintain a diary regarding the types of movement undertaken during the 7-day period that would aid in estimating the proportion of the accelerometer signal that reflects walking and its limitations versus other types of physical activity such as sports, chores, and gardening. Our assumption is that most activity undertaken by ambulatory persons with MS involves walking, but no data have been published yet supporting or refuting this possibility. This assumption should be addressed in future research, given that accelerometer counts have reflected both walking limitations and physical activity in previous samples of persons with MS.4,5 Another limitation is the demographic composition and size of the sample. The sample mostly consisted of white women with a relatively brief disease duration, and all participants had relapsing-remitting MS. Future researchers would do well to recruit a more diverse sample with a greater degree of disability that is characteristic of a longer duration and progressive types of MS. This is relevant given our previous research indicating that accelerometer counts are more strongly associated with self-report measures of walking limitations than with physical activity in ambulatory-impaired persons with MS.2 The sample size itself was small, and a larger sample with greater variability in scores would allow for greater precision in estimating correlations, as well as examining the strength of associations, in subsamples such as those with mild, moderate, and severe disability. Another limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study. This design did not afford an assessment of sensitivity. The next limitation is that the presence of the researchers might have biased the walking behavior (ie, speed) and oxygen cost of walking during the 6MWT. An additional limitation is that we only included 1 brand and model of accelerometer. The ActiGraph model 7164 accelerometer is uniaxial and primarily, but not exclusively, detects movement in the vertical axis when worn around the waist. This unit and the site of monitoring would not be very sensitive for picking up additional, nonvertical body movements while walking (eg, trunk movements and ataxia) that are characteristic of gait deterioration. To capture this signal and evaluate its importance for free-living monitoring of walking limitations, researchers should consider the application of triaxial accelerometers that capture vertical, horizontal, and perpendicular displacement of the body during ambulatory movements. Such a device might provide an even more meaningful signal for the measurement of walking limitations in MS. One final limitation is that we did not include a control group for examining the possibility that the relationship between accelerometry and the other measures is unique to those with MS.

CONCLUSIONS

We provide evidence that extends the validity of inferences from accelerometry as a measure of walking limitations based on associations with the 6MWD and the oxygen cost of walking (ie, objective markers) in persons with MS. We await continued investigations of the validity and responsiveness of this metric versus other markers of walking limitations in MS, as this will highlight the comparative value of accelerometry for capturing real-life locomotor limitations. Such continued examination is warranted because accelerometers have been identified as a criterion st0andard for measuring ambulatory mobility in neurologic disorders.2

List of Abbreviations

- 6MWD

6-minute walk distance

- 6MWT

6-minute walk test

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- MSWS-12

Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale-12

- PDDS

Patient Determined Disease Steps

- PS

Performance Scales

Footnotes

No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on the authors or on any organization with which the authors are associated.

Suppliers

Health One Technology, 15 W Main St, Pensacola, FL 32502.

Microsoft, One Microsoft Way, Redmond, WA 98052

CST Berger, Stanley MW50, Suite 1, 480 Myrtle St, New Briton, CT 06053.

Velo 5; CatEye, 2-8-25 Kuwazu Higashi Sumiyoshi-ku, Osaka 546, Japan.

Cosmed K4b2; Cosmed, Via dei Piani di Mt. Savello 37, Pavona di Albano - Rome, I-00041, Italy.

Detecto 338; Cardinal Scale Manufacturing Co, 203 E Daugherty, Webb City, MO 64870.

References

- 1.Hobart JC, Riazi A, Lamping DL, Fitzpatrick R, Thompson AJ. Measuring the impact of MS on walking ability: the 12-item MS Walking Scale (MSWS-12) Neurology. 2003;60:31–36. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearson OR, Busse ME, van Deursen RW, Wiles CM. Quantification of walking mobility in neurological disorders. QJM. 2004;97:463–475. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hch084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dishman RK, Washburn RA, Schoeller DA. Measuring physical activity. Quest. 2001;53:295–309. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snook EM, Motl RW, Gliottoni RC. The effect of walking mobility on the measurement of physical activity using accelerometry in multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:248–258. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weikert M, Motl RW, Suh Y, McAuley E, Wynn D. Accelerometry in persons with multiple sclerosis: measurement of physical activity or walking mobility? J Neurol Sci. 2009;290:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motl RW, Snook EM. Confirmation and extension of the validity of the Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale-12 (MSWS-12) J Neurol Sci. 2008;268:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motl RW, Snook EM, Wynn DR, Vollmer T. Physical activity correlates with neurological impairment and disability in multiple sclerosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:492–495. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318177351b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motl RW, Schwartz CE, Vollmer T. Continued validation of the Symptom Inventory in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;285:134–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butland RJA, Pang J, Gross ER, Woodcock AA, Geddes DM. Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking in respiratory disease. BMJ. 1982;284:1607–1608. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6329.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman MD, Marrie RA, Cohen JA. Evaluation of the six-minute walk in multiple sclerosis subjects and healthy controls. Mult Scler. 2008;14:383–390. doi: 10.1177/1352458507082607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chetta A, Rampello A, Marangio E, et al. Cardiorespiratory response to walk in multiple sclerosis. Respir Med. 2004;98:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savci S, Inal-Ince D, Arikan H, et al. Six-minute walk distance as a measure of functional exercise capacity in multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27:1365–1371. doi: 10.1080/09638280500164479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waters S, Mulroy S. The energy expenditure of normal and pathological gait. Gait Posture. 1999;9:207–231. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(99)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motl RW, Dlugonski D, Weikert M, Agiovlasitis S, Fernhall B, Goldman M. Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale-12 and oxygen cost of walking. Gait Posture. 2010;31:506–510. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olgiati R, Jacquet J, Di Prampero PE. Energy cost of walking and exertional dyspnea in multiple sclerosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:1005–1010. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.5.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Messick S. Validity of psychological assessment: validation of inferences from persons’ responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. Am Psychol. 1995;50:741–749. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGuigan C, Hutchinson M. Confirming the validity and responsiveness of the Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale-12 (MSWS-12) Neurology. 2004;62:2103–2105. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000127604.84575.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadjimichael O, Kerns RB, Rizzo MA, Cutter G, Vollmer T. Persistent pain and uncomfortable sensations in persons with multiple sclerosis. Pain. 2007;127:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]