Abstract

This study examined differences between Asians and non-Hispanic Whites (Whites) in pain sensitivity, and its relationship to mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR). In 30 Whites (50% female) and 30 Asians (50% female), experimental pain sensitivity was assessed with a hand cold pressor task, yielding measures of pain threshold, tolerance, intensity, and unpleasantness. Mean arterial pressure and HR measurements taken at rest and in response to speech stress were assessed. Perceived stress, anxiety, perfectionism, parental criticism, parental expectations and depressive symptoms were also measured. The results indicated that for the cold pain test, Asians demonstrated significantly lower pain threshold and tolerance levels than Whites. Although no ethnic differences were seen for MAP or HR responses to stress, for whites higher stress MAP levels were correlated with reduced pain sensitivity, while for Asians higher baseline and stress HR levels were correlated with reduced pain sensitivity. Asians reported higher parental expectations and greater parental criticism than Whites. For Asians only, higher levels of perfectionism were related to more depressive symptoms, anxiety and perceived stress. These results indicate that Asian Americans are more sensitive to experimental pain than Whites and suggest ethnic differences in endogenous pain regulatory mechanisms (e.g. MAP and HR). The results may also have implications for understanding ethnic differences in clinical pain.

Keywords: pain sensitivity, ethnic differences, Asians, blood pressure, heart rate, perfectionism

Introduction

While ethnic disparities in clinical and experimental pain sensitivity are well established, most of this research has been conducted comparing African Americans to non-Hispanic Whites (Whites) (Edwards et al., 2001; Green et al., 2003; McCraken et al., 2001; Riley et. al., 2002). Few studies have examined pain sensitivity in Asians. Among patients with terminal and endstage chronic illness, patients of color (12.2% Asian, 17.8% African American, 9% Latino, 6.7% Other) experience increased clinical pain compared to Whites (Rabow and Dibble, 2005,) and Asians report a higher prevalence of and more widespread musculoskeletal pain than Whites (Palmer, 2007; Allison et al., 2002; Macfarlane et al., 2005). Regarding sensitivity to experimental pain, Asians have lower sensory and pain thresholds in the trigeminal face region (Komiyama et al., 2007, 2009), lower pain thresholds to heat pain (Watson et al., 2005), are more sensitive to capsaicin induced pain (Gazerani et al., 2005), and exhibit lower tolerance to mechanical pressure (Woodrow et al., 1972) than both Whites and African Americans.

There have been no studies examining the biopsychosocial determinants of pain sensitivity in Asians, though ethnic differences in endogenous pain regulatory mechanisms may play a role. Higher blood pressure (BP) levels are associated with decreased pain sensitivity, although the majority of this research has been conducted in Whites (Campbell et al., 2004; France et al., 2002; Guasti et al., 2002). The relationship between BP and pain sensitivity has been conceptualized within the context of the defense reaction, with evidence that sensory and autonomic responses to painful stimuli act in concert to modify pain perception (Maixner, 1991). Increased BP stimulates mechanoreceptive afferents (i.e. baroreceptors) which, upon stimulation, decrease sympathetic drive, thereby lowering BP. Additionally, stimulation of these baroreceptors decreases cortical arousal and diminishes somatomotor reflexes evoked by noxious stimuli indicative of analgesic-like effects (Dworkin et al., 1979; Maixner, 1991; Randich and Maixner, 1986). Only one report exists examining ethnic differences in cardiovascular-somatosensory interactions. Mechlin et al. (2005) found that while higher BP was related to reduced pain sensitivity in Caucasians, this relationship was absent in African Americans.

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship of endogenous pain regulatory mechanisms to experimental pain sensitivity in Asians and Whites. We also compared the ethnic groups for depression and anxiety symptoms, since both predict pain sensitivity (Bar et al., 2006; Dickens et al., 2003, Frot et al., 2004; Janssen et al., 2000; Lautenbacher, 1999; Rhudy and Meagher, 2000). We also examined perfectionism since Asians endorse more perfectionism, including parental expectations and parential criticisms, than Whites (Castro and Rice, 2003; Chang, 1998; Yoon and Lau, 2008), and other studies indicate that perfectionism is associated with clinical pain (Bottos et al., 2004; Kowal et al., 1990, Liebman, 1978; 2004). We hypothesized that Asians, relative to non-Hispanic Whites, would show increased pain sensitivity and an absence of a relationship involving BP and pain sensitivity, similar to African Americans (Mechlin et al. 2005). A secondary hypothesis was that Asians would report higher levels of perfectionism, depression, and anxiety than Whites.

Methods

Participants

The protocol was approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board and informed written consent was obtained from all participants. Participants were recruited through informational emails at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, as well as through the Introductory Psychology Participant Pool. The sample consisted of 30 Asians (50% female) and 30 non-Hispanic Whites (50% female). Race was determined by self-identification on a questionnaire, and no individuals who self-identified as being of more than one race were included. All Whites were born in the US, while 50% of Asians were born in Asia, including South Korea (40%), China (46.6%), and India (13.3%). Those born in Asia had lived in the US on average of 4 years. All participants were healthy, normotensive and did not take any prescription medication (including oral contraceptives), had no self-reported current signs of clinical depression (based on the requirement that Beck Depression Inventory scores < 10), did not indicate abuse of alcohol or other drugs, and did not endorse current use of over-the-counter medication or herbal supplements. Participants received $25 compensation for their participation if they were recruited through informational emails or 1.5 hours of research credit for their Introductory Psychology course if they were recruited through the psychology participant pool. Participants were asked to refrain from any caffeine or over-the-counter medication, including analgesics, and to refrain from exercise for 24 hours prior to the onset of the experiment. To control for menstrual cycle effects on pain sensitivity (Helström et al., 2000, Pfleeger et al., 1997; Riley et al., 1999), women were tested during the follicular phase (days 1-10) of their menstrual cycles.

Three experimenters conducted the study: a White female, a White male, and an Asian female. Race of the experimenter was randomized. To confirm that no ethnic × gender group was more likely to be tested by a certain experimenter, chi-square analyses were preformed. The results indicated that there were no differences in the proportion of participants from each ethnic or gender group who were tested by a specific experimenter (X 2 (2) = 0.68 to 2.57s, ps > .10).

Procedure

Following informed written consent, the participants’ BP was taken (to confirm normotensive status). Participants then filled out self-reported questionnaires: medical history information, the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983), Spielberger Trait Anxiety Scale (Spielberger, 1983), the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck and Beamesderfer, 1974), and the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (Frost et al., 1990) which includes 6 subscales [Concern over Mistakes (CM), Doubts about actions (D), Parental Expectations (PE), Parental Criticism (PC), Personal Standards (PS), and Organization (O)], and then underwent the following procedures:

Hand Cold Pressor Task

The apparatus for the cold pressor task consisted of a cooler filled with ice-water at a temperature of 4°C. A water circulatory device prevented the temperature from warming around the participant’s hand. The participant was informed, before the start of the task, to place his/her hand into the water up to a designated point on the wrist. The participant was asked to indicate when the sensation in his/her hand first became painful (threshold) by saying “painful” and to indicate when s/he was no longer willing or able to tolerate the pain (tolerance) by saying “stop”. After saying stop, but before removing his/her hand from the water, the participant was asked to rate two different aspects of the pain: unpleasantness and intensity, using a 0-100 Likert scale, with 0 being no pain and 100 being the most intense/unpleasant pain imaginable. There was a maximum time limit (5 minutes) imposed, though participants were not aware of the exact time limit.

Instrumentation

Immediately following the cold pain task, participants were instrumented for BP and HR using the SunTech BP monitor model 4240. Before the onset of the baseline, at least 3 manual stethoscopic BP measurements were taken simultaneously with the automated readings to ensure the accuracy of microphone placement, and cuff position, and to ensure accurate recordings.

Baseline Rest

The baseline period consisted of 10 minutes of quiet rest. Baseline measures included HR and BP measurements taken at minutes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9. For each variable (HR and mean arterial pressure (MAP)), the 5 separate measurements were average to constitute one baseline value.

Speech Stressor

The average time between the start of the cold pressor task and the start of the speech stressor was on average 35 minutes (range 24 – 50 minutes). The speech stressor included the following: 1) Instructions (5 min): Participants were instructed that they would be asked to give a 5 minute speech as a job interview for their ideal job. In order to increase subjective stress, participants were told that their speech would be judged by a “selection committee” (composed of two experimenters) and that the researchers were trained in voice and behavioral analysis, and that they would be tape-recorded while they spoke; 2) Preparation Period (5 min): Participants were left alone to make notes about their speech. They were told that they would not be able to refer to these notes during their speech. BP and HR were taken at minutes 1, 3, and 5, and were averaged to constitute preparation values; 3) Speech (5 min): Immediately following the preparation, participants were asked to deliver their speech in front of the interviewing committee. If the participant was unable to talk for the entire time allotment (5 minutes), the experimenters asked prepared questions to ensure that the participant continued to speak for the duration of the task. During the speech, BP and HR measurements were taken at minutes 1, 3, and 5, and then averaged to constitute speech levels.

Blood pressure measures were not taken during the cold pressor test since inflation of the blood pressure cuff on the contralateral arm may have acted as a counter-irritant stimulus eliciting diffuse noxious inhibitory control mechanisms, and thereby altering pain sensitivity to the cold pressor (Edwards et al., 2004). Other studies have reliably used blood pressure responses to mental stress tests as predictors of pain sensitivity to cold pressor pain (Girdler et al., 2005; Mechlin et al., 2005).

Data Reduction and Analysis

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics presented in Table 1 were examined using a 2 (Ethnicity: White/Asian) × 2 (Gender: Male/ Female) analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Table 1.

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics as a Function of Ethnicity and Gender (N=60)

| Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Asian Female (n=15) | Asian Male (n=15) | White Female (n=15) | White Male (n=15) |

| Age (years) A | 24.27 (5.48) | 20.80 (5.16) | 18.93 (0.96) | 18.87 (0.92) |

| Educational BackgroundA | 07.00 (1.00) | 06.13 (0.52) | 06.00 (0.00) | 5.87 (0.52) |

| BMI | 21.83 (4.09) | 23.68 (2.89) | 22.91 (3.62) | 24.96 (4.83) |

| Resting MAP (mmHg) A | 80.07 (6.81) | 81.00 (7.94) | 75.27 (6.99) | 77.33 (4.85) |

| Resting Heart Rate (mmHg) | 67.60 (12.00) | 67.64 (8.29) | 65.20 (6.61) | 67.73 (12.46) |

Asians > non-Hispanic Whites, p<.05

For Education each individual was assigned a score of 1-8 based on the following criteria: 1= Grades 0-4; 2 = Grades 5-8; 3 = Some High School; 4 = Graduated High School; 5 = Trade School or Business College; 6= Some College; 7 = College Degree; 8 = Post-graduate Degree

BMI= Body Mass Index

Differences in pain threshold and pain tolerance were examined for the cold pain test using a 2 (Ethnicity: White/Asian) × 2 (Gender: Male/ Female) × 2 (Time point: Pain Threshold/Pain Tolerance) repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Time point as the repeated factor. Differences in pain intensity and unpleasantness ratings were each examined using a 2 (Ethnicity) × 2 (Gender) ANOVA.

Because mean arterial pressure (MAP) reflects both systolic and diastolic blood pressure and represents the average arterial pressure during a cardiac cycle, and in order to reduce Type I error rates, we chose to analyze MAP instead of systolic and diastolic blood pressure in separate analyses.

Differences in cardiovascular measures [mean arterial pressure (MAP), and HR (HR)] were examined using a 2 (Ethnicity) × 2(Gender) × 3 (Condition: Baseline/Preparation/Speech Stress) repeated measures ANOVA, with condition as the repeated factor. Differences in psychosocial measures [Perfectionism, each Perfectionism subscale (PE, PC, D, PS, O, CM), Depression, Anxiety, and perceived stress] were each examined using a 2 (Ethnicity) × 2 (Gender) ANOVA.

A series of Pearson product moment correlational analyses were conducted separately by ethnicity to examine relationships between cardiovascular measures and pain sensitivity as well as the relationship between the psychosocial measures. In order to reduce Type I error rates, all correlational analyses were collapsed across gender to focus exclusively on differences between ethnic groups, consistent with the primary aims of the study.

It should be noted that although correlational analyses analyzing the relationship between psychosocial measures and pain sensitivity were considered, because these analyses would not have be driven by a priori hypotheses, and because of the excessive number of correlational analyses that would have been run in a relatively small sample, the likelihood for increasing Type I error rates and for finding spurious results argued against conducting these analyses.

Results

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

General demographic means are summarized in Table 1. Asians were older (F (1,58) = 13.56, p<.01), had higher levels of education (F (1,58) = 15.7, p<.01), and higher resting mean arterial pressure (MAP; F(1,58)= 2.20, p<.01) than Whites. There were no ethnic or gender differences in BMI or resting HR.

Effects of Ethnicity and Gender on Cold Pain Sensitivity

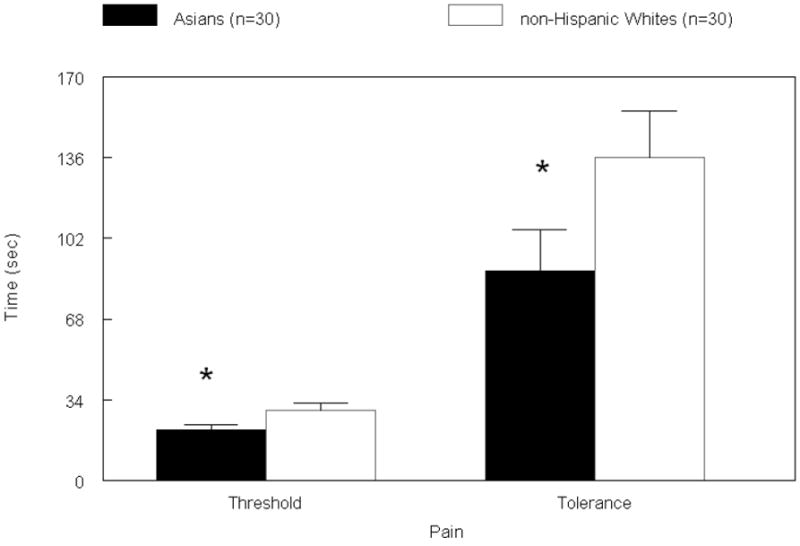

As summarized in Figure 1, Asians were more sensitive to cold pressor pain than Whites for both pain threshold and pain tolerance levels (F(1,56) = 4.21, p < .05). As expected, women were more sensitive to cold pressor pain than men regardless of race (threshold: 21.40 vs. 29.23; tolerance: 86.63 vs. 137.7; F(1,58)= 4.39, p<.05). There were no significant interactions between ethnicity and gender.

Figure 1.

Cold Pain Threshold and Tolerance as a Function of Ethnicity

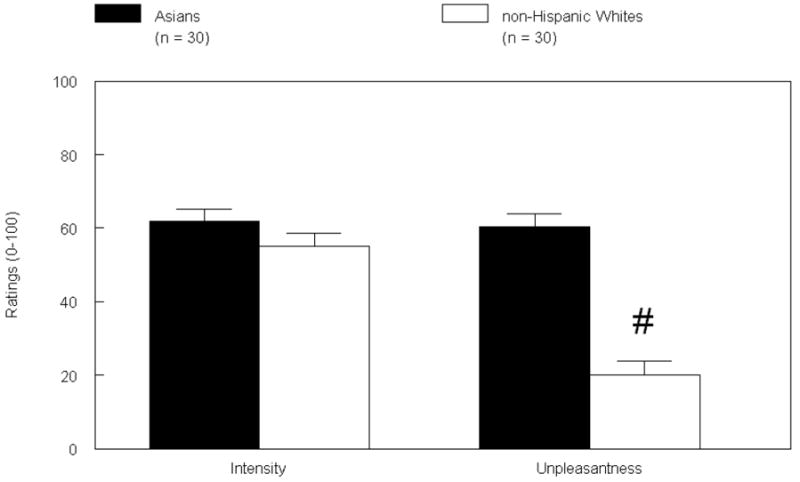

Analyses indicated that Asians rated the cold pressor task as marginally more unpleasant than Whites (Figure 2; F(1,56) = 3.59, p < .06). This difference corresponded to a medium effect size based on Cohen’s d statistic (d = 0.50; r = .24). There were no ethnic differences in intensity ratings. There were no gender differences in intensity or unpleasantness ratings, nor were there any gender × ethnicity interactions.

Figure 2.

Cold Pain Intensity and Unpleasantness as a Function of Ethnicity

Cardiovascular Reactivity to Stress

Heart rate and MAP during the different periods of the study are summarized in Table 2. The speech stressor elicited a significant response in all participants, since both HR and MAP levels were significantly higher during the preparation and speech period than during baseline (Fs (2,108) = 101.91 and 265.94, ps<.0001). No ethnic or gender differences in cardiovascular levels during stress were observed, nor were there any ethnic by gender interactions. Post hoc analyses were conducted using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with resting MAP as a covariate in order to control for the resting difference in MAP between the two ethnic groups, and still no significant ethnic differences in MAP during preparation and speech were found. To confirm that the speech task was in fact stressful for the participants, a subjective stress questionnaire was administered, asking the participant to rate how tense they felt on a scale of 0-10, 0 being not at all tense and 10 being the most tense imaginable. Both Asians (Mean=5.6, SD=2.6) and Whites (Mean=5.97, SD=2.22) found the task to be stressful. The difference between the groups was not significant.

Table 2.

HR and MAP as a Function of Ethnicity and Gender (N=60)

| Mean (±SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Asian Female (n=15) | Asian Male (n=15) | White Female (n=15) | White Male (n=15) |

| HR at Rest | 67.60 (11.98) | 67.64 (8.29) | 65.20 (6.61) | 67.73 (12.46) |

| HR at Preparatory | 77.93 (13.48) | 77.36 (10.94) | 74.00 (7.80) | 77.07 (10.17) |

| HR at Stress | 78.93 (13.18) | 83.93 (10.48) | 84.13 (11.31) | 83.60 (11.76) |

| MAP at Rest | 80.07 (6.81) | 81.00 (7.94) | 75.27 (6.99) | 77.33 (4.85) |

| Map at Preparatory | 88.40 (8.33) | 89.13 (8.28) | 84.47 (8.83) | 87.87 (6.23) |

| Map at Stress | 100.14 (13.46) | 99.73 (8.19) | 95.50 (7.57) | 99.47 (8.81) |

Ethnic Differences in Psychosocial Measures

While there were no ethnic differences in overall perfectionism, (Table 3; F(1,59) = 0.05, p > .10), Asians reported higher parental expectations than Whites (F(1,59) = 7.51, p < .01). For the parental criticism subscale, there was evidence for an ethnic × gender interaction (F(1, 59) = 2.93, p < .08), since Asian females reported more parental criticism than White females, (F(1,59) = 5.47, p < .05), while there were no ethnic differences in parental criticism in males. The difference in parental criticism between Asian and White females corresponded to a large effect size based on Cohen’s d statistic (d = 0.85; r = 0.39). No ethnic or gender differences were observed for any other perfectionism subscale. Thus, only the overall perfectionism, parental expectations and parental criticisms scales were examined in subsequent correlational analyses. Women had higher perceived stress scores than men (F(1, 58) = 4.04, p < .05). No ethnic, gender, or ethnic × gender interactions were seen for depressive or anxiety symptoms.

Table 3.

Mean (±SD) Psychosocial Characteristics as a Function of Ethnicity

| Mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial Variables | Asian Females (n=15) | Asian Males (n=15) | White Females (n=15) | White Males (n=15) |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 4.47 (5.71) | 1.67 (1.76) | 3.20 (2.40) | 2.73 (2.58) |

| Spielberger Trait Anxiety | 38.00 (9.98) | 32.53 (6.72) | 34.33 (6.08) | 36.20 (9.70) |

| Perceived Stress Scale A | 22.27 (9.44) | 16.73 (4.06) | 21.27 (3.86) | 20.13 (6.60) |

| Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale | 109.00 (15.66) | 103.13 (15.80) | 103.93 (10.84) | 106.53 (14.67) |

| Parental Expectations B | 17.73 (3.88) | 17.93 (3.88) | 14.67 (3.74) | 16.00 (2.42) |

| Parental Criticism C | 11.87 (3.14) | 10.20 (2.31) | 9.60 (2.06) | 10.27 (2.91) |

| Doubts about Actions | 9.80 (3.49) | 8.80 (2.73) | 9.80 (3.47) | 10.40 (3.25) |

| Personal Standards | 24.07 (4.37) | 24.87 (3.18) | 25.93 (2.66) | 25.27 (5.27) |

| Organization | 24.40 (3.87) | 22.33 (5.07) | 23.07 (4.27) | 22.53 (5.46) |

| Concern over Mistakes | 20.20 (5.03) | 19.07 (5.68) | 19.93 (4.18) | 21.00 (4.88) |

Women > Men, p<.05

Asians > non-Hispanic Whites, p<.01

Asian Females > non-Hispanic White Females, p<.05

Relationship of Cardiovascular Variables to Pain Sensitivity

As shown in Table 4, for pain intensity and unpleasantness ratings, only Whites showed the expected inverse relationship between MAP and pain sensitivity during speech preparation. Higher speech preparation MAP was associated with decreased pain intensity and unpleasantness (rs = -0.42 and -0.44, ps<.05).

Table 4.

Correlations between Physiological Variables and Pain Sensitivity as a Function of Ethnicity

| Physiological Variables | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold Pain Measures | Baseline MAP

|

Preparation MAP

|

Speech MAP

|

Baseline HR

|

Preparation HR

|

Speech HR

|

||||||

| Asians | Whites | Asians | Whites | Asians | Whites | Asians | Whites | Asians | Whites | Asians | Whites | |

| Threshold | 0.15 | -0.04 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.19 | -0.06 | 0.24 | -0.10 | 0.27 | -0.19 | 0.35 | 0.12 |

| Tolerance | 0.15 | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.28 | -0.09 | 0.13 | -0.11 | -0.01 | -0.09 | 0.34 |

| Intensity | -0.14 | -0.21 | -0.19 | -0.42* | -0.10 | -0.34 | -0.50** | -0.09 | -0.55** | -0.27 | -0.52** | -0.30 |

| Unpleasantness | 0.01 | -0.23 | -0.15 | -0.44* | -0.03 | -0.24 | -0.38 | -0.03 | -0.31 | -0.19 | -0.24 | -0.06 |

p < .05

p<.01

In Asians, there were no significant relationships between any MAP measure and pain sensitivity. However, in Asians, higher baseline, preparation, and speech HR was associated with lower pain intensity (rs = -0.50 to -0.55, ps < .01), and higher baseline HR was associated with lower pain unpleasantness ratings (r = -0.38, p<.05). In summary, the general pattern of effects suggest that for Whites, higher BP levels during stress are associated with reduced pain sensitivity, while for Asians higher HR at rest an during stress is associated with reduced pain sensitivity.

Relationship of Perfectionism Measures to other Psychosocial Measures

As summarized in Table 5, while the expected intercorrelations between perceived stress, depressive symptoms and anxiety symptoms were seen for both ethnic groups, only for Asians was perfectionism and parental criticism positively correlated with depressive symptoms, trait anxiety and perceived stress (rs= 0.41 to 0.86, ps<.05).

Table 5.

Intercorrelations between Psychosocial Variables as a Function of Ethnicity

| Psychosocial Variables | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial Variables | Depression

|

Trait Anxiety

|

Perceived Stress

|

Total Perfectionism Score

|

Parental Expectations

|

Parental Criticism

|

||||||

| Asians | Whites | Asians | Whites | Asians | Whites | Asians | Whites | Asians | Whites | Asians | Whites | |

| Depression | ---- | ---- | 0.68** | 0.58** | 0.68** | 0.46** | 0.41* | 0.28 | 0.44* | 0.09 | 0.50** | 0.21 |

| Trait Anxiety | 0.68** | 0.58** | ---- | ---- | 0.86** | 0.69** | 0.58** | 0.29 | 0.39* | 0.07 | 0.59** | 0.18 |

| Perceived Stress | 0.68** | 0.49** | 0.86** | 0.69** | ---- | ---- | 0.49** | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.54** | 0.09 |

p < .05

p < .01

Post-hoc Analyses Comparing Asians Born in the United States with those Born in Asia

To the extent that socio-cultural differences between Asians born in the U.S. (n=15) and those born in Asia (n=15) would influence psychosocial, stress and pain measures, post hoc analyses were conducted comparing these groups with ANOVA. Relative to those born in Asia, Asians born in the US scored higher on the overall perfectionism scale (113.9 +/- 3.4 vs. 97.14 +/- 3.6), on the parental criticism subscale (12.3 +/- 0.62 vs. 9.57 +/- 0.67), and on the parental expectation subscale (19.7 +/- 0.82 vs. 15.7 +/- 0.89) (Fs(1,28) = 8.88 – 11.47, ps < .01). There were no differences between the two Asian groups in pain sensitivity or cardiovascular stress responses.

Discussion

For the first time, we documented that not only do Asians residing in the United States enhanced sensitivity to experimental pain relative to Whites, as has been documented in other parts of the world (Gazerani et al., 2005, Komiyama et al., 2007, 2009, Watson et al., 2005), but that Asians and Whites may differ in endogenous pain regulatory mechanisms. Specifically, while we observed the expected inverse relationship between MAP and pain sensitivity, this was seen in the Whites only. It must be acknowledged, however, that this relationship was most evident during speech preparation. On the other hand, a more robust relationship between higher HR and reduced pain sensitivity was found in Asians that was evident for both resting, speech preparation and speech conditions. These preliminary results are consistent with other research showing ethnic differences in endogenous pain regulatory mechanisms in African Americans compared with Whites (Mechlin, 2005; 2007).

While the reason(s) for the differences between Asians and Whites in endogenous pain regulatory mechanisms (i.e., MAP versus HR) is unknown, one possibility may relate to ethnic differences in the contribution of β-adrenergic receptors to pain regulation. It is well known that cardiac β-adrenergic receptors mediate HR responses to stress (Girdler, 1993). Contribution of sympathetic nervous system activation to pain states has long been implicated (Hord et al., 2003; Janicik, 2003). An important role for β-adrenergic receptors in mediating increased pain perception under these circumstances comes from: 1) animal and in vitro models showing that activation of the β-adrenergic receptors result in hyperalgesia (Ferreira, 1980; Khasar, 1999; Khasar, 2003); 2) human studies showing that infusions of epinephrine result in anginal pain in the absence of ischemia (Eriksson, 2005); and 3) human studies showing that propranolol (a β-adrenergic receptor antagonist) is effective in reducing clinical pain in patients with TMD and fibromyalgia (Light et al., 2009). While the Asians in this study did not have greater HR levels at rest or in response to stress than the Whites, nonetheless, there was a robust relationship involving both resting and stress-induced HR levels and pain sensitivity in the Asians that was not evident in the Whites. Future studies examining pain sensitivity and β-adrenergic receptor responsivity (e.g. via the standardized isoproterenol sensitivity test; Cleaveland, 1972) or β-adrenergic receptor blockade in Asians relative to Whites would be needed to confirm or refute a role for β-adrenergic receptor involvement in the heightened experimental and clinical pain experienced by Asians. Should involvement of β-adrenergic receptor mechanisms in heightened pain sensitivity be established in Asians in future research, this would have important implications for ethnic differences in the pathophysiology of pain perception and would identify potential therapeutic targets for pain management.

It is also worth mentioning that unlike the ethnic differences in pain sensitivity seen between African Americans and Whites, where it has been consistently shown that African Americans have reduced pain tolerance but no difference in pain threshold (Campbell et al., 2005; Edwards and Fillingim, 1999; Mechlin et al., 2005), we found that Asians show both reduced pain tolerance and reduced pain threshold relative to Whites. The experience of pain involves at least two dimensions: sensory discriminatory and affective motivational dimensions (Auvray et al., 2008). Evidence suggests that pain tolerance and unpleasantness reflect the affective motivational dimension of pain, whereas pain threshold and intensity reflect the sensory discriminatory dimension (Price et al., 2002). The majority of studies, which have generally focused on African Americans and non-Hispanic Whites, have shown that the sensory discriminative aspects of pain (threshold and intensity) do not vary across ethnic groups (Campbell et al. 2005; Chapman and Jones, 1944; Sheffield et al., 2002; Woodrow et al., 1972; Zatzick and Dimsdale, 1990), while pain unpleasantness and tolerance (affective motivational aspects) are more susceptible to ethnic differences (Edwards and Fillingim, 1999; Riley et al., 2002; Sheffield et al., 2000; Watson et al. 2005). This study found Asians to have lower pain tolerance and higher ratings of pain unpleasantness, providing further support for the concept that affective motivational aspects of pain are susceptible to ethnic differences, and extending this finding to Asians. On the other hand, our finding for lower pain threshold levels in Asians differs from past research with African Americans, but is consistent with one other study comparing Asians to Whites since they found that Asians had lower pain threshold to a thermal pain test than Whites, though no measure of pain tolerance was obtained in that study (Watson et al., 2005). Considering that Asians have been under researched in regards to pain perception, additional research is needed to determine if our finding for ethnic differences in both the sensory discriminatory and the affective motivational dimension of pain in Asians compared with Whites is confirmed. If confirmed, based on the evidence that sensitivity to experimental pain procedures predicts clinical pain (Fillingim et al., 1996), these results would have implications for understanding determinants of ethnic differences in clinical pain that may be unique to Asians and/or for tailoring Asian-specific pain reduction interventions.

Regarding psychosocial profiles of the Asians and Whites, the groups did not differ in depressive or anxious symptoms or in perceived stress. Moreover, for both groups, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and perceived stress were positively intercorrelated as would be expected. Therefore, it appears unlikely that these factors are responsible for the ethnic differences observed in pain sensitivity. However, only for Asians did high scores on parental expectations and parental criticisms correlate with higher depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and perceived stress. These results suggest that parental expectations and criticisms may have much more robust effects on psychological well-being in Asians than in Whites, extending prior research indicating that the influence of parental expectations and criticisms on adjustment might vary in important ways for students from more collectivist than individualist cultures (Castro and Rice, 2003; Chang et al., 2004; Kawamura et al., 2002; Pfleeger et al., 1997; Sindrup and Jensen 1999). Thus, parental evaluation may function as a chronic stressor in Asians, much as discrimination is conceptualized as a chronic stressor in African Americans (Broudy et al., 2007; James 2003). This interpretation is limited, however, by the correlational nature of our research and by the relatively low levels of depressive and anxious symptoms experienced by our sample, even in the Asians.

Interestingly, this interpretation must also be modified based on the socio-cultural environment in which the Asian subjects were raised. Our post hoc analyses indicated that the ethnic differences in measures of perfectionism, described above, were driven largely by the Asians native to the US, since they reported higher levels of overall perfectionism, parental criticisms, and parental expectations than Asians born in Asia but who had been residing in the U.S. for, on average, only four years. Hence, there appears to be something unique to the Asian American culture in terms of social norms that increase the drive toward perfectionism. While the sample size is small and these findings should only be considered as preliminary trends, further research on ethnic differences in psychosocial function might focus on individual subcultures. It should also be noted that while the two Asian groups differed in perfectionism, our post hoc analyses indicated no differences in pain sensitivity. Thus, the socio-cultural factors driving increased perfectionism in Asian Americans does not appear to contribute to their altered pain perception.

While the novel findings reported here are intriguing, limitations of this study should also be pointed out. First, the samples were relatively homogeneous with respect to age (18-26 years of age) and all were free of any current depressive or anxiety symptoms. Thus, these results may not generalize to older individuals or to those with clinical levels of depression or anxiety – factors that are associated with greater rates of clinical pain (Bar et al., 2006; Bar et al., 2005; Klatzkin et al., 2007, Lautenbacher, 1994, 1999; Sindrup and Jensen, 1999). Another limitation is there were significant differences in age (Asians older), education level (Asians higher) and MAP (Asians higher MAP at rest) than Whites. Thus, the possibility exists that these differences may have contributed to the ethnic differences in pain sensitivity that we observed. However, the research linking age to differences in pain sensitivity focuses on much larger differences in age such as different developmental periods or the elderly (Farrell et al., 2007). Thus, it is doubtful that age contributed to the observed effects since the age difference observed (22 versus 19 years of age, on average) is unlikely to be of relevance with respect to experimental pain sensitivity. Similarly for education level, the differences were slight and the greater education level in the Asians likely reflected their slightly older age as the majority of subjects were enrolled as students at the University of North Carolina.

Regarding resting MAP differences, while this might well influence pain sensitivity, if anything higher MAP levels that were observed in the Asians would be expected to result in less sensitivity to pain (Campbell et al., 2004; Chapman and Jones, 1944; Edwards and Fillingim, 1999; France et al., 2002; Guasti et al., 1999; Guasti et al., 2002; Maixner, 1991; Sheffield et al., 2000; Woodrow et al., 1972) the opposite relationship observed in the present study since the Asians had higher MAP but were more sensitive to pain. In fact, it could be argued that the absence of a BP-pain sensitivity relationship despite elevated MAP levels, provides even stronger evidence suggesting alterations in BP-pain regulatory mechanisms in Asians. Moreover, we controlled for MAP levels in analyses and the results remained unaltered. It should also be noted, that the cold pressor task and the speech tasks were not counter-balanced; therefore, there could be potential carry-over of stress responsive measures to the subsequent speech task, but this is unlikely given the average time between the end of the cold pressor task and the start of the speech task was 35 minutes.

Finally, we must acknowledge that for correlational analyses, this study had a relatively small sample size; which may have lead to spurious findings, though the consistent pattern of effects involving HR levels and pain sensitivity in Asians and the relationship of the perfectionism measures to mood symptoms in the Asians, both of which were absent in the Whites, suggests some level of robustness to our findings even with the small sample. Certainly, the study should be considered preliminary and serve a heuristic value, informing future, larger scale studies. Despite these limitations, and although the underlying mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated, this study confirms the prior limited research that Asians exhibit enhanced pain sensitivity to experimental pain relative to Whites, and extends this research by suggesting that ethnic differences in endogenous pain regulatory factors may contribute to these ethnic differences in pain sensitivity. If confirmed these results may have important implications for understanding determinants of ethnic differences in pain that may be unique to Asians and/or implications for tailoring Asian-specific pain reduction interventions. Additional research on ethnic differences involving Asians should also be conducted in chronic pain patients where relationships of perfectionism to mood state may be expected to exert a clinically relevant influence.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH-RO1-DA013705 and the Office of Undergraduate Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The authors wish to thank Dot Faulkner for assistance with manuscript preparation and submission.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allison TR, Symmons DP, Brammah T, Haynes P, Rogers A, Roxby M, Urwin M. Musculoskeletal pain is more generalised among people from ethnic minorities than among white people in Greater Manchester. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:151–156. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auvray M, Myin E, Spence C. The sensory-discriminative and affective-motivational aspects of pain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34(2):214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bär KJ, Brehm S, Boettger M, Boettger S, Wagner G, Sauer H. Pain perception in major depression depends on pain modality. Pain. 2005;117(1):97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bär KJ, Brehm S, Boettger M, Wagner G, Boettger S, Sauer H. Decreased sensitivity to experimental pain in adjustment disorder. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(5):467–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Beamesderfer A. Assessment of depression: The depression inventory. In: Pichot P, editor. Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology: Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry. Karger; Basel, Switzerland: 1974. pp. 151–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottos S, Dewey D. Perfectionists’ Appraisal of Daily Hassles and Chronic Headache. Headache. 2004;44(8):772–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broudy VC, Hickman S. Perceived ethnic discrimination in relation to daily moods and negative social interactions. J Behav Med. 2007;30(1):31–43. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell TS, Hughes JW, Girdler SS, Maixner W, Sherwood A. Relationship of ethnicity, gender, and ambulatory blood pressure to pain sensitivity effects of individualized pain rating scales. Clin J Pain. 2004;5:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.02.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in responses to multiple experimental pain stimuli. Clin J Pain. 2005;113:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro J, Rice K. Perfectionism and ethnicity: Implications for depressive symptoms and self-reported academic achievement. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2003;9(1):64–78. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman WP, Jones CM. Variations in cutaneous and visceral pain sensitivity in normal subjects. J Clin Invest. 1944;23:81–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI101475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E. Cultural differences, perfectionism, and suicidal risk in a college population: Does social problem solving still matter? Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1998;22(3):237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, Banks KH, Watkins AF. How adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism relate to positive and negative psychological functioning: Testing a stress-mediation model in Black and White female college students. J Counsel Psychol. 2004;51.1:93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cleaveland CR, Rangno RE, Shand DG. A standardized isoproterenol sensitivity test. Arch Intern Med. 1972;130:47–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.130.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens C, McGowan L, Dale S. Impact of depression on experimental pain perception: A systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(3):369–375. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000041622.69462.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin BR, Filewich RJ, Miller NE, Craigmyle N, Pickering TG. Baroreceptor activation reduces reactivity to noxious stimulation: implications for hypertension. Science. 1979;205(4412):1299–1301. doi: 10.1126/science.472749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CL, Fillingim RB, Keefe F. Race, ethnicity and pain. Pain. 2001;94:133–137. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in thermal pain responses. Psychosom Med. 1999;61(3):346–354. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199905000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RR, Ness TJ, Fillingim RB. Endogenous Opioids, Blood Pressure, and Diffuse Noxious Inhibitory Controls: A Preliminary Study. Percept Mot Skills. 2004;99(2):679–687. doi: 10.2466/pms.99.2.679-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson B, Svedenhag J, Martinsson A, Sylven C. Effect of epinephrine infusion on chest pain in syndrome X in the absence of signs of myocardial ischemia. Am Cardiol. 1995;75:241–245. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(95)80028-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M, Gibson S. Age interacts with stimulus frequency in the temporal summation of pain. Pain Med. 2007;8(6):514–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira SH. Local analgesic effect of morphine on the hyperalgesia induced by cAMP, Ca2+, isoprenaline, and PGE2. Adv Prostaglandin Thromboxane Research. 1980;8:1207–1215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Kincaid S, Sigurdsson A, Harris MB. Pain sensitivity in patients with temporomandibular disorders: relationship to clinical and psychosocial factors. Clin J Pain. 1996;12(4):260–269. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199612000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France CR, Froese SA, Stewart JC. Altered central nervous system processing of noxious stimuli contributes to decreased nociceptive responding in individuals at risk for hypertension. Pain. 2002;98:101–108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R. The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990;14(5):449–468. [Google Scholar]

- Frot M, Feine JS, Bushnell MC. Sex differences in pain perception and anxiety. A psychophysical study with topical capsaicin. Pain. 2004;108:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazerani P, Arendt-Nielsen L. The impact of ethnic differences in response to capsaicin-induced trigeminal sensitization. Pain. 2005;117(1):223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girdler SS, Maixner W, Naftel HA, Stewart PW, Moretz R, Light KC. Cigarette smoking, stress-induced analgesia and pain perception in men and women. Pain. 2005;114:372–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girdler SS, Pedersen CA, Stern RA, Light KC. Menstrual cycle and premenstrual syndrome: modifiers of cardiovascular reactivity in women. Health Psychol. 1993;12(3):180–92. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.3.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green CR, Baker TA, Sato Y, Washington TL, Smith EM. Race and chronic pain: a comparative study of young black and white Americans presenting for management. J Pain. 2003;4:176–183. doi: 10.1016/s1526-5900(02)65013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guasti L, Gaudio G, Zanotta D, Grimoldi P, Petrozzino MR, Tanzi F, Bertolini A, Grandi AM, Venco A. Relationship between a genetic predisposition to hypertension, blood pressure levels and pain sensitivity. Pain. 1999;82:311–317. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guasti L, Zanotta D, Mainardi LT, Petrozzino MR, Grimoldi P, Garganico D, Diolisi A, Gaudio G, Klersy C, Grandi AM, Simoni C, Cerutti S. Hypertension-related hypoalgesia, autonomic function and spontaneous baroreflex sensitivity. Auton Neurosci Basic Clin. 2002;99:127–133. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(02)00052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helström B, Lundberg U. Pain perception to the cold pressor test during the menstrual cycle in relation to estrogen levels and a comparison with men. Integr Psychol Behav Sci. 2000;35(2):132–141. doi: 10.1007/BF02688772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hord ED, Cohen SP, Cosgrove GR, Ahmed SU, Vallejo R, Chang Y, Stojanovic MP. The predictive value of sympathetic block for the success of spinal cord stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:626–633. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000080061.26321.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James SA. Confronting the moral economy of US racial/ethnic health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):189. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicki TI. Chronic pelvic pain as a form of complex regional pain syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;46:797–803. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200312000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen SA, Arntz A. Anxiety and pain: attentional and endorphinergic influences. Pain. 1996;66:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura KY, Frost RO, Harmatz MG. The relationship of perceived parenting styles to perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32:317–327. [Google Scholar]

- Khasar SG, McCarter G, Levine JD. Epinephrine produces a β–adrenergic receptor-mediated mechanical hyperalgesia and in vitro sensitization of rat nociceptors. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1104–1112. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.3.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasar SG, Green PG, Miao FJ-P, Levine JD. Vagal modulation of nociception is mediated by adrenomedullary epinephrine in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:909–915. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatzkin R, Mechlin B, Bunevicius R, Girdler S. Race and histories of mood disorders modulate experimental pain tolerance in women. Pain. 2007;8(11):861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiyama O, Kawara M, De Laat A. Ethnic differences regarding tactile and pain thresholds in the trigeminal region. Pain. 2007;8(4):363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiyama O, Wang K, Svensson P, Arendt-Nielsen L, Kawara M, De Laat A. Ethnic differences regarding sensory, pain, and reflex responses in the trigeminal region. Clin J Neurophysiology. 2009;120(2):384–389. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal A, Pritchard D. Psychological characteristics of children who suffer from headache: A research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1990;31(4):637–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenbacher S, Roscher S, Strian D, Fassbender K, Krumrey K, Krieg JC. Pain perception in depression: relationships to symptomatology and naloxone-sensitive mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 1994;56(4):345–52. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenbacher S, Spernal J, Schreiber W, Krieg JC. Relationship between clinical pain complaints and pain sensitivity in patients with depression and panic disorder. Psychosom Med. 1999;61(6):822–7. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199911000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman WM. Recurrent Abdominal Pain in Children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1978;17(2):149–153. doi: 10.1177/000992287801700208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light K, Bragdon E, Grewen K, Brownley K, Girdler S, Maixner W. Adrenergic Dysregulation and Pain With and Without Acute Beta-Blockade in Women With Fibromyalgia and Temporomandibular Disorder. Pain. 2009;10(5):542–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane GJ, Palmer B, Roy D, Afzal C, Silman AJ, O’Neill T. An excess of widespread pain among South Asians: are low levels of vitamin D implicated? Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1217–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.032656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maixner W. Interactions between cardiovascular and pain modulatory systems: Physiological and pathophysiological implications. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1991;2:S3–S12. [Google Scholar]

- McCraken LM, Matthews AK, Tang TS, Cuba SL. A comparison of blacks and whites seeking treatment for chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(3):249–255. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechlin M, Maixner W, Light K, Fisher J, Girdler S. African Americans show alterations in endogenous pain regulatory mechanisms and reduced pain tolerance to experimental pain procedures. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):948–956. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188466.14546.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechlin B, Morrow A, Maixner W, Girdler S. The relationship of allopregnanolone immunoreactivity and HPA-axis measures to experimental pain sensitivity: Evidence for ethnic differences. Pain. 2007;131(1):142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer B, Macfarlane G, Afzal C, Esmail A, Silman A, Lunt M. Acculturation and the prevalence of pain amongst South Asian minority ethnic groups in the UK. J Rheumatol. 2007;46:1009–1014. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleeger M, Straneva P, Fillingim R, Maixner W, Girdler S. Menstrual cycle, blood pressure and ischemic pain sensitivity in women: A preliminary investigation. Int J Psychophysiol. 1997;27(2):161–166. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(97)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DD. Central neural mechanisms that interrelate sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Mol Interv. 2002;2(6):392–403. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.6.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabow MW, Dibble SL. Ethnic differences in pain among outpatients with terminal and end-stage chronic illness. Pain Med. 2005;6(3):235–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randich A, Maixner W. The role of sinoaortic and cardiopulmonary baroreceptor reflex arcs in nociception and stress-induced analgesia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;467:385–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb14642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, Wade JB, Myers CD, Sheffield D, Papas RK, Price DD. Racial/ethnic differences in the experience of chronic pain. Pain. 2002;100:291–298. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhudy J, Meagher M. Fear and anxiety: Divergent effects on human pain thresholds. Pain. 2000;84(1):65–75. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield D, Biles PL, Orom H, Maixner W, Sheps DS. Race and sex differences in cutaneous pain perception. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:517–523. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. Efficacy of pharmacological treatments of neuropathic pain: an update and effect related to mechanism of drug action. Pain. 1999;83(3):389–400. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y) Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Watson P, Latif R, Rowbotham D. Ethnic differences in thermal pain responses: A comparison of South Asian and White British healthy males. Pain. 2005;118(1):194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow K, Friedman G, Siegelaub A, Collen M. Pain tolerance: Differences according to age, sex and race. Psychosom Med. 1972;34(6):548–556. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J, Lau AS. Maladaptive Perfectionism and Depressive Symptoms Among Asian American College Students: Contributions of Interdependence and Parental Relations. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2008;14(2):92–101. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatzick D, Dimsdale J. Cultural variations in response to painful stimuli. Psychosom Med. 1990;52(5):544–557. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]