Abstract

The Bombyx mori fibroin light (L)-chain gene was cloned and the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene inserted into exon 7. The chimeric L-chain–GFP gene was used to replace the polyhedrin gene of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcNPV). This recombinant virus was used to target the L-chain–GFP gene to the L-chain region of the silkworm genome. Female moths were infected with the recombinant virus and then mated with normal male moths. Genomic DNA from their progenies was screened for the desired targeting event. This analysis showed that the chimeric gene had integrated into the L-chain gene on the genome by homologous recombination and was stably transmitted through generations. The chimeric gene was expressed in the posterior silk gland, and the gene product was spun into the cocoon layer.

Keywords: Gene targeting, transgenesis, baculovirus, silkworm

Lepidopteran insects and their cells are very useful as hosts for the production of heterologous proteins by baculovirus expression vectors (Luckow and Summers 1988; Miller 1988). However, gene expression is transient, because the infected cells ultimately die from virus infection and the polyhedrin promoter is expressed only during the very late phase of infection. For this reason, the IE1 promoter from NPV (Jarvis et al. 1990; Jarvis 1993) or a densovirus promoter (Giraud et al. 1992) has been utilized for stable transformation of lepidopteran cells and constitutive expression of foreign genes. Attempts to develop similar transient expression systems in silkmoths have failed, because plasmid DNAs injected into silkworm eggs were rapidly degraded (Nagaraju et al. 1996).

Although AcNPV can replicate in the silkworm, Bombyx mori, the AcNPV-infected larvae survive and grow without any symptoms of nuclear polyhedrosis (Mori et al. 1995). Previously, we reported that AcNPV could be utilized as a vector for the transovarian transmission of foreign genes in the silkworm (Mori et al. 1995). The luciferase gene was introduced into the AcNPV genome, female fifth instar larvae were inoculated with the recombinant virus, and luciferase activity was detected in the larvae of subsequent generations, indicating the luciferase gene had been vertically transmitted. Densoviruses are also considered to be candidate transfer vectors for transgenesis of lepidopteran insect cells and stable expression of foreign genes (Giraud et al. 1992). On the other hand, transgenesis of Drosophila melanogaster is routinely accomplished by use of the P-element transposon and this has facilitated the analysis of developmental regulation of gene expression (Rubin and Spradling 1982). Recently, germ-line transformation of dipteran insects has been established for the purpose of genetically controlling the Mediterranean fruit fly (Handler et al. 1998; Jasinskiene et al. 1998), and mosquitoes have been genetically transformed with insect transposable elements Hermes and Mariner to control diseases such as yellow fever and malaria (Zwiebel et al. 1995; Coates et al. 1998).

In this report we examine the transgenesis by homologous recombination to carry out gene targeting and ferry transgene into the silkworm B. mori.

Results and Discussion

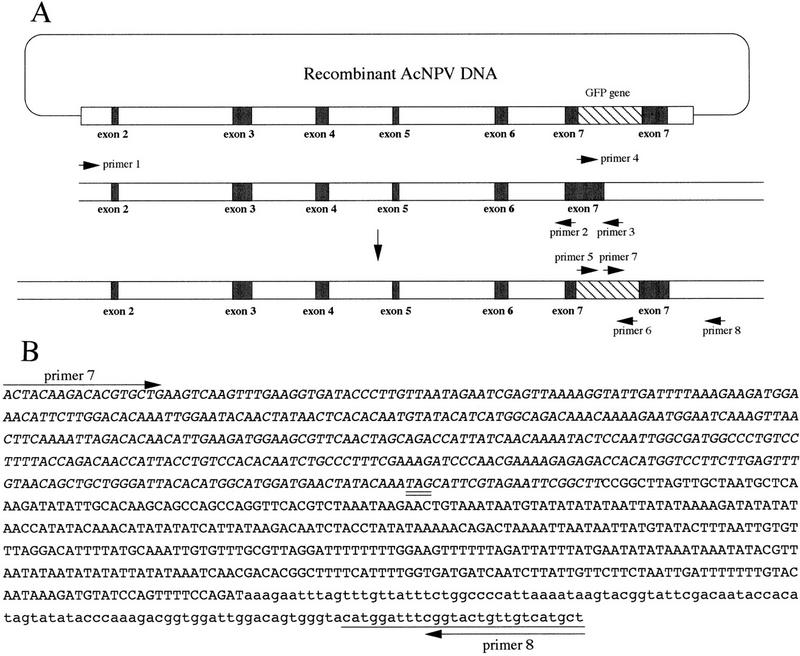

Because fibroin, which consists of heavy (H) and light (L) chains, is one major protein of silk and the most abundant protein produced by the silkworm, the fibroin promoter would be a useful promoter for the production of large quantities of heterologous proteins. We constructed a vector for the purpose of gene targeting in the silkworm, B. mori. As shown in Figure 1A, the 5-kb upstream (long arm) and 0.5-kb downstream (short arm) sequence of exon 7 of the L-chain gene (Kikuchi et al. 1992) were cloned, and then a green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene (Chalfie et al. 1994) was inserted between the long- and short-arm sequences. The chimeric L-chain–GFP gene was transferred into the polyhedrin region of AcNPV, and the recombinant virus was used as a targeting vector. Homologous recombination was expected to occur between the long- and short-arm sequences common to both the chimeric L-chain gene in the virus and the L-chain gene in the B. mori genome. The chimeric gene should then be expressed as an L-chain–GFP fusion protein under the control of the L-chain promoter. The ORF of the chimeric gene was terminated by the stop codon (TAG) of the GFP gene (Fig. 1B). One-day-old fifth instar female larvae (F0) were injected with 50 μl containing 5 × 105 plaque forming units (PFU) of the recombinant virus by percutaneous inoculation. Approximately 50 animals were inoculated in each experiment (Table 1). Although normal larval–pupal ecdysis was observed, pupal–adult metamorphosis was arrested. Metamorphosis, however, resumed after administration of ecdysteroid hormone (Mori et al. 1995). The average durations of the larval and pupal stages in the uninfected animals were 10 and 15 days, respectively, but the duration of the pupal stage of infected animals was a few days longer than in the uninfected animals. This phenomenon suggested that the ecdysteroid UDP–glucosyltransferase (EGT) gene of AcNPV was expressed, and the secreted EGT altered growth of the infected animals (Shikata et al. 1998). After infection with the recombinant baculovirus, no progeny virus was detected in hemolymph at 5, 10, or 15 days postinoculation (p.i.), but 2.3 × 102 and 5.4 × 105 PFU/ml of progeny virus were detected in hemolymph at 20 and 25 days p.i., respectively. The progeny virus was propagated and the viral DNA was extracted. Restriction endonuclease analysis of the viral DNA indicated that the progeny virus was derived from the injected recombinant virus and not from the activation of a latent virus present in the silkworm (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Homologous recombination between the targeting vector and endogenous DNA. (A) Targeting vector (top), intron and exon of L-chain gene (middle), and a product of the targeting event by homologous recombination (bottom). (B) Nucleotide sequence of the intron–exon boundary in the vicinity of exon 7. The 0.9-kb product amplified by PCR with primers 7 and 8 was sequenced. The sequence of the GFP gene is shown in italics. The sequences of exon 7 and intron are shown by uppercase and lowercase letters, respectively. The downstream sequence beyond the end of targeting vector and the stop codon (TAG) in the chimeric gene are underlined and double underlined.

Table 1.

Frequency of gene targeting in the silkworm

|

Experiment

|

No. of inoculated F0 larvaea

|

No. of F0 larvae yielding GFP-positive embryos (% positive)b

|

No. of F1 siblings containing GFP gene/no. tested (% positive)c

|

No. of F2larvae with targeted recombinationde

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

male

|

female

|

||||

| 1 | 51 | 3 (5.9) | 2/125 (1.6) | 0 | 0 |

| 4/141 (2.8) | 1 | 0 | |||

| 4/119 (3.4) | 1 | 0 | |||

| 2 | 47 | 1 (2.1) | 0/149 | N.D. | N.D. |

| 3 | 46 | 1 (2.2) | 10/138 (7.2) | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | 53 | 2 (3.8) | 1/110 (0.9) | 0 | 0 |

| 4/108 (3.7) | 0 | 1 | |||

| 5 | 55 | 1 (1.8) | 4/156 (7.1) | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 252 | 8 (3.2) | 29/1046 (2.7) | 5 | 2 |

Female fifth instar larvae were inoculated with recombinant AcNPV and mated with normal moths.

Genomic DNA pools were prepared from 100 embryos from each inoculated F0 larvae and tested for the presence of GFP by PCR with primers 5 and 6.

Approximately 100–150 siblings from each F0 that produced PCR-positive embryos were reared, and individuals were tested for the presence of the GFP gene by PCR with primers 5 and 6.

Genomic DNA from F2 larvae was analyzed by PCR using primers 7 and 8, which detect a novel DNA junction between GFP and chromosomal DNA.

(N.D.) Not determined.

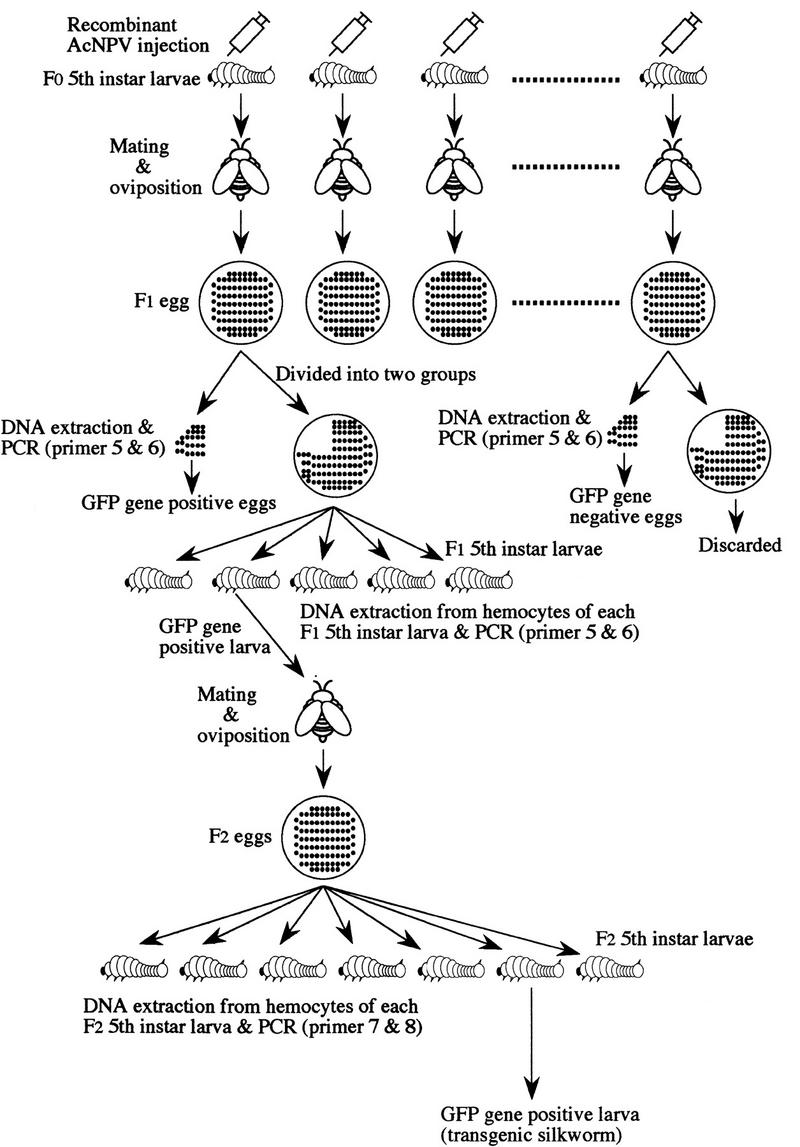

An outline of the screening method for gene targeting is shown in Figure 2, and the frequency of gene targeting is summarized in Table 1. Virus-inoculated female moths were mated with a normal male moth (Fig. 2). The genomic DNA was extracted from 100 embryos and used as the template for PCR with primers 5 and 6 to screen for the presence of the GFP gene. Approximately 3% of the inoculated F0 gave rise to F1 embryos that were positive by PCR and dot blot hybridization (Table 1). The larvae from the remaining PCR-positive siblings were reared, whereas the PCR-negative siblings were discarded. About 100–150 F1 individuals were collected, and hemocytes of each fifth instar larva were harvested from each individual separately. Genomic DNA was extracted from the hemocytes and screened by PCR analysis with primers 5 and 6. Overall, ∼2.7% of all the F1 individuals tested were positive for the GFP gene (Table 1). Male and female moths containing this gene were mated with normal moths, and their progenies (F2) were reared. About 150 offspring were produced from each cross and hemocytes were harvested separately from each larvae in fifth instar. Genomic DNA from the hemocytes was assayed for gene targeting by a PCR screening method that specifically detects a novel DNA junction created by the targeting event. Only homologous recombination can juxtapose the two sequences that create this junction, one from the GFP gene in the targeting vector, and the other within the downstream sequence beyond the end of the targeting vector (Fig. 1A). As shown in Figure 3A, the PCR reaction with genomic DNA (lane 3) and primers 7 and 8 amplified a 0.9-kb DNA fragment, showing that the targeting vector correctly recombined with the genomic DNA. The same results were obtained with the six other F2s. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the 0.9-kb PCR product from all F2 animals indicated that one of homologous recombination occurred at the 3′ end of the transgene in the targeting vector (Fig. 1B). After inoculation of 252 animals of the fifth instar larvae (F0) with the recombinant AcNPV, the gene targeting event was ultimately detected in seven individuals that derived from different F1 parents and, thus represent the distinct targeting events that occurred at a frequency of ∼0.16% (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Scheme of the screening method for analysis of gene targeting.

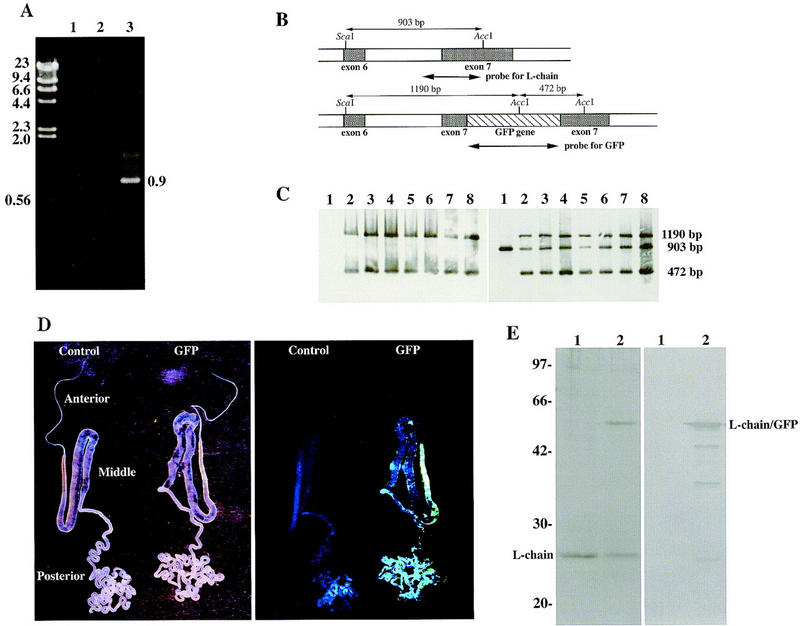

Figure 3.

Screening for gene targeting. (A) Screening by PCR analysis. Primer 7 (5′-ACTACAAGACACGTGCTG-3′) in the GFP gene and primer 8 (5′-AGCATGACAACAGTACCG-3′) in the intron of downstream of exon 7 were synthesized to screen silkworms for homologous recombination events by PCR. As the normal L-chain gene contained no binding sites for primer 7 and the targeting vector contained no binding sites for primer 8, only the homologous recombinant allele could contain both priming sites. The targeting event was demonstrated by amplification of the 0.9-kb PCR product. (Lane 1) Negative control containing water instead of template DNA; (lane 2,3) genomic DNA from hemocytes of a control larva and a tested larva, respectively. The size (kb) of the DNA markers is shown at left. (B) Gene map of the periphery of exons 6 and 7. The AccI and ScaI sites are indicated in the L-chain gene (top) and the chimeric gene(bottom). The lengths of restriction enzyme fragments and each probe are also shown. (C) Southern blot analysis of silkworm genomic DNAs. Genomic DNA was digested with AccI and ScaI and analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with probes for the GFP gene (left) or the L-chain (exon 7) gene (right). (Lane 1) Genomic DNA from a control larva; (lanes 2–8) genomic DNA from larvae in which the 0.9-kb PCR product was amplified. (D) Green fluorescence under the irradiation of long wavelength UV light. Silk glands were dissected (left) and exposed to long wavelength ultraviolet light (right). Silk glands from the control animal and the GFP gene-targeted animal are shown as control and GFP, respectively. (E) SDS-PAGE (left) and Western blot analysis (right) of silk protein. (Lane 1) Normal cocoon layer; (lane 2) cocoon layer from the GFP gene-targeted animal. Antibody used in the Western blot analysis was specific for GFP. The sizes (kD) of protein markers is shown at left.

To confirm further that the targeting event occurred by homologous recombination, Southern blot analysis was performed. Genomic DNA was digested with AccI and ScaI, and Southern blot hybridization was performed with the GFP gene or a portion of the L-chain gene as a probe (Fig. 3B). Two bands with the expected sizes were detected when the GFP probe was hybridized to the genomes from the seven animals from with which the 0.9-kb PCR product had been amplified (Fig. 3C). With the L-chain gene as a probe, a single band was detected in the genome from control larvae and two additional fragments were detected in the seven larvae that scored positive for the 0.9-kb PCR product (Fig. 3C). This result showed that the chimeric gene had been introduced into the L-chain gene of the transgenic silkworms by a gene-targeting event and that one copy was present per haploid genome of each individual.

When the silk gland was dissected and exposed to long wavelength UV light, emission of green fluorescence was observed from that of the GFP gene-targeted silkworm larvae and no green fluorescence was observed from control larvae (Fig. 3D). The green fluorescence was also observed from the larval intersegmental membrane, because the intersegmental membrane forms a flexible joint and is transluscent. Two subunits of fibroin (H and L chains) are synthesized in the posterior silk gland, and the organ is located in the posterior abdomen. Therefore, we concluded that the chimeric L-chain–GFP gene was probably expressed in the posterior silk gland. SDS-PAGE analysis revealed a new protein with a molecular mass of 52 kD and decreased amounts of L chain (25 kD) in the silk protein of an F2 animal as compared with a normal animal (Fig. 3E). The molecular mass of the new protein correlated to with that of the chimeric protein consisting of L chain (25 kD) and GFP (27 kD). Furthermore, the new protein band reacted with an antibody against GFP (Fig. 3E), indicating that the silk protein prepared from cocoons of targeted F2 animals was composed of the chimeric L-chain–GFP gene. Cocoons produced by GFP gene-targeted silkworms did not appear any different from normal cocoons and green fluorescence was not observed under the irradiation of long wavelength UV light. It is necessary to study the physiochemical properties of the cocoons and the raw silk. These findings indicated that the chimeric protein was synthesized under the control of the L-chain promoter in the posterior silk gland and secreted into the cocoon layer.

When male and female F2 animals were mated with normal animals and segregation of the GFP gene in the F3 generation was analyzed by dot blot hybridization, about one-half of the individuals contained this gene (Table 2). When the GFP gene-targeted F3 animals were crossed with normal animals and the GFP gene-targeted animals, about one-half and three-fourths of the individuals scored positive for the GFP gene, respectively (Table 2). These results indicate that the chimeric gene was entirely localized to a single chromosome in the F2 generation of the silkworm and that a germ-line integration event had occurred at the F1 stage. Although the genomic DNA from individuals of each generation was used as a template for detection of AcNPV DNA, the viral DNA was detected in only the F0 and F1 generations.

Table 2.

Segregation patterns of the GFP gene in the F3 and F4 generation

|

Mating

|

No. of F3 or F4 animals testeda

|

No. of GFP-positive larvae (% tested)

|

|---|---|---|

| F3 | ||

| Control (♀) × F2 (♂) from exp. 1)b | 92 | 43 (46.7) |

| Control (♀) × F2 (♂ from exp. 5)b | 95 | 49 (51.6) |

| F2 (♀ from exp. 3) × control (♂)b | 96 | 46 (47.9) |

| F2 (♀ from exp. 4) × control (♂)b | 90 | 44 (48.9) |

| F4 | ||

| F3 (♀) × control (♂)c | 91 | 42 (46.2) |

| Control (♀) × F3 (♂)c | 98 | 50 (51.0) |

| F3 (♀) × F3 (♂)c | 96 | 70 (72.9) |

Genomic DNA from hemocytes of each 5th instar larva (F3) was extracted, and the GFP gene was analyzed by PCR amplification.

F2 male and female animals were derived from each experiment (Table 1).

GFP gene-targeted F3 male and female animals were obtained by the cross of F2 generation.

P-element transgenesis of D. melanogaster or of other insects with transposons is dependent on the random integration of a foreign gene (O’Brochta and Atkinson 1996). Recombinant baculovirus-mediated transgenesis of the silkworm allowed specific alterations in a target sequence. Targeted disruption of an endogenous gene would permit analysis of gene function through the production of gene knockouts in the silkworm. In addition, homologous recombination of a foreign gene downstream from a powerful promoter, such as the fibroin promoter, would allow large-scale and constitutive production of a useful protein in the silkworm (Marshall 1998). Thus, the genetic manipulations described in this study will be important in clarifying the regulation of gene expression and introducing new traits into beneficial insects.

Materials and methods

Construction of targeting vector and PCR amplification

PCR primers were synthesized for the 5.0-kb long-arm and the 0.5-kb short-arm DNA fragments according to the published sequence data for the L-chain gene (Kikuchi et al. 1992). The genomic DNA of fifth instar larvae was extracted from hemocytes by use of a DNA extraction kit (Stratagene). The primers synthesized for PCR amplification of long-arm DNA fragment were: primer 1 as a forward primer (5′-AATTAGCTCTAGATGAGCTCCCGGCGTACC-3′) and primer 2 as a reverse primer (5′-CAACTAAGGGATCCGCGTCATTACCGTTGC-3′). In the reverse primer, the AAGCCGGTCGCG sequence included in the exon 7 of L-chain gene was converted into AAGGGATCCGCG, resulting in a creation of a BamHI site. PCR amplification was carried out with the LA PCR kit (TaKaRa) with 0.4 mm of each primer and 200 ng of genomic DNA as template. After heating the reaction mixture (50 μl) in MicroAmp reaction tubes (PE Applied Biosystems) at 94°C for 1 min in a Gene AmpPCR System 2400 (PE Applied Biosystems), amplification was carried out for 30 cycles of denaturation (20 sec at 98°C) and annealing extension (15 min at 68°C). A final 10-min step at 72°C was performed at the completion of these cycles. The long arm was excised with XbaI and BamHI, and the fragment was inserted into baculovirus transfer vector pVL1392 (PharMingen) at the XbaI and BamHI sites to obtain pVLFL-5K. Primer 3 (5′-TACCCACTGTCCAATCCACCG-3′) and primer 4 (5′-CCGGCTTAGTTGCTAATGCTC-3′) were synthesized for amplification of the short-arm DNA fragment. Primer 5 (5′-GGAGAAGAACTTTTCACTGGAG-3′) and primer 6 (5′-ATCCATGCCATGTGTAATCCC-3′) were used to screen for the GFP gene. Primer 7 (5′-ACTACAAGACACGTGCTG-3′) in the GFP gene and primer 8 (5′-AGCATGACAACAGTACCG-3′) in the intron downstream of exon 7 were synthesized for screening the targeting event. These PCR amplifications were carried out in a reaction mixture (50 μl) containing 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mm KCl, 200 mm dNTP, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.4 mm of each primer, 2.5 units of rTaq DNA polymerase (TOYOBO), and 200 ng of the genomic DNA as template. MicroAmp reaction tubes were used with AmpliWax PCR Gems (PE Applied Biosystems) for an auto-hot start. After heating the reation mixture at 80°C for 5 min and cooling to 5°C for 30 sec in a Gene AmpPCR System 2400 (PE Applied Biosystems), amplification was carried out for 35 cycles of denaturation (1 min at 94°C), annealing (1 min at 55°C) and extension (2 min at 72°C). A final 7-min step at 72°C was performed at the completion of these cycles. PCR products were cloned into pCR2.1 vector (Invitrogen). The short arm was excised with EcoRI and inserted into the pGFPcDNA vector (Clontech) at the dephosphorylated EcoRI site to construct pGFP–0.5K. BamHI and StuI fragments were separated from pGFP–0.5K and ligated with an BamHI adaptor at the StuI site. The resulting 1.2-kb BamHI fragment composed of the GFP gene and the short-arm DNA fragment was inserted into pVLFL–5K at the dephosphorylated BamHI site, and the recombinant baculovirus transfer vector, pAcFLGFP, was constructed. Spodoptera flugiperda IPLB-SF21AE cells were transfected with 5 μg of the recombinant transfer vector and 0.5 μg of linearized AcNPV DNA, Baculogold Baculovirus DNA (PharMingen). A recombinant AcNPV (targeting vector) rescued by the transfer vector was isolated and plaque purified.

Dot blot hybridization

Following PCR amplification, 10 μl of the PCR sample was immobilized on a nylon membrane (Amersham) with a vacuum manifold. GFP cDNA was excised from the pGFPcDNA vector and used as a probe for hybridization. Detection of PCR products was carried out with the ECL direct nucleic acid labeling and detection system (Amersham).

Analysis of nucleotide sequence

The nucleotide sequence of the intron–exon boundary of the L-chain gene was determined by the dideoxytermination method carried out with a 373A DNA Sequencing system (PE Applied Biosystems).

Southern blot analysis and Western blot analysis

The GFP gene was excised from the pGFPcDNA vector (CLONTECH) with BamHI and EcoRI and used as a probe. A probe for the L-chain gene was prepared by PCR amplification. The primers were designed to amplify a part of the L-chain gene (Fig. 3B). Primer 9 (5′-TTTTTAATTATCCACAGCTC-3′) and primer 10 (5′-GTCTGTTTTTATATAGGTAG-3′) were synthesized. The PCR amplification was carried out in a reaction mixture (50 μl) containing 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mm KCl, 200 mm dNTP, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.4 mm of each primer, 2.5 units of rTaq DNA polymerase (Toyobo), and 200 ng of the genomic DNA as template. MicroAmp reaction tubes were used with AmpliWax PCR Gems (PE Applied Biosystems) for an auto-hot start. After heating the reation mixture at 80°C for 5 min and cooling to 5°C for 30 sec in a Gene AmpPCR System 2400 (PE Applied Biosystems), amplification was carried out for 35 cycles of denaturation (1 min at 94°C), annealing (1 min at 55°C) and extension (2 min at 72°C). A final 7-min step at 72°C was performed at the completion of these cycles. Southern blot analysis was performed on silkworm genomes after digestion with AccI and ScaI (Fig. 1A). Electrophoresed genomic DNA was transferred to Hybond-N membranes (Amersham), and hybridization was performed with a commercially available digoxigenin DNA labeling and detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim) according to the supplier’s instructions. Western blot analysis for chimeric protein expression was performed on silk proteins from the cocoon layer. To dissolve the silk protein, 150 ml of 70% LiSCN was added to 5 mg of the cocoon layer, and 40 ml of 62.5 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 6.8) containing 2% SDS and 5% 2-mercaptoethanol was added to 10 ml of the dissolved silk protein. The silk protein (20 μl) was then subjected to 12.5% SDS-PAGE, and the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose. The nitrocellulose blot was placed in protein-blocking solution [20 mm Tris-HCl, 500 mm NaCl at pH 7.5 (TBS) containing 3% gelatin] for 1 hr, and the blots were treated overnight with rabbit anti-GFP antibody (CLONTECH). The blots were then treated with goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Bio-Rad) at a 1:3000 dilution for 1 hr, and Konica Immunostaining HRP-1000 was used for signal detection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. L. Guarino and D. Jarvis for critically reviewing the manuscript and for helpful discussions. This work was supported by Enhancement of Center of Excellence, Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology, Science and Technology Agency, Japan. M.Y. was supported by the Research Fellowships of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL hmori@pc.kit.ac.jp; FAX 81-75-724-7760.

References

- Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates CJ, Jasinskiene N, Miyashiro L, James AA. Mariner transposition and transformation of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:3748–3751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraud C, Devauchelle G, Bergoin M. The Densovirus of Junonia coenia (JcDNV) as an insect cell expression vector. Virology. 1992;186:207–218. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90075-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handler AM, McCombs SD, Fraser MJ, Saul SH. The lepidopteran transposon vector, piggyBac, mediates germ-line transformation in the Mediterranean fruit fly. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:7520–7525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis DL. Effects of baculovirus infection on IE1-mediated foreign gene expression in stably transformed insect cells. J Virol. 1993;67:2583–2591. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2583-2591.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis DL, Fleming JGW, Kovacs GR, Summers MD, Guarino LA. Use of early baculovirus promoters for continuous expression and efficient processing of foreign gene products in stably transformed lepidopteran cells. Bio-Technology. 1990;8:950–955. doi: 10.1038/nbt1090-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinskiene N, Coates CJ, Benedict MQ, Cornel AJ, Rafferty CS, James AA, Collins FH. Stable transformation of yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti, with the Hermes element from the housefly. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:3743–3747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi Y, Mori K, Suzuki S, Yamaguchi K, Mizuno S. Structure of the Bombyx mori fibroin light-chain-encoding gene: Upstream sequence elements common to the light and heavy chain. Gene. 1992;110:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90642-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckow VA, Summers MD. Trends in the development of baculovirus expression vector. BioTechnology. 1988;6:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall A. The insects are coming. Nat Biotechnology. 1998;16:530–533. doi: 10.1038/nbt0698-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LK. Baculoviruses as gene expression vectors. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1988;42:177–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.001141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori H, Yamao M, Nakazawa H, Sugahara Y, Shirai N, Matsubara F, Sumida M, Imamura T. Transovarian transmission of a foreign gene in the silkworm, Bombyx mori, by Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Bio-Technology. 1995;13:1005–1007. doi: 10.1038/nbt0995-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraju J, Kanda T, Yukihiro K, Chavancy G, Tamura T, Couble P. Attempt at transgenesis of the silkworm (Bombyx mori L.) by egg-injection of foreign DNA. Appl Entomol Zool. 1996;31:587–596. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brochta DA, Atkinson PW. Transposable elements and gene transformation in non-drosophilid insects. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;26:739–753. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(96)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GM, Spradling AC. Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science. 1982;218:348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.6289436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikata M, Shibata H, Sakurai M, Sano Y, Hashimoto Y, Matsumoto T. The ecdysteroid UDP-glucosyltransferase gene of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus alters the moulting and metamorphosis of a non-target insect, the silkworm, Bombyx mori (Lepidoptera, Bombycidae) J Gen Virol. 1998;79:1547–1551. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-6-1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwiebel LJ, Saccone G, Zacharopoulou A, Besansky NJ, Favia G, Collins FH, Louis C, Kafatos FCL. The white gene of Ceratitis capitata: A phenotypic marker for germline transformation. Science. 1995;270:2005–2008. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]