Summary

The circadian clock coordinates cellular and organismal energy metabolism [1]. The importance of this circadian timing system is underscored by findings that defects in the clock cause deregulation of metabolic physiology and result in metabolic disorders [2]. On the other hand, metabolism also influences the circadian clock, such that circadian gene expression in peripheral tissues is affected in mammalian models of obesity and diabetes [3, 4]. However, to date there is little to no information on the effect of metabolic genes on the central brain pacemaker which drives behavioral rhythms. We have found that the AKT and TOR-S6K pathways, which are major regulators of nutrient metabolism, cell growth, and senescence, impact the brain circadian clock that drives behavioral rhythms in Drosophila. Elevated AKT or TOR activity lengthens circadian period, whereas reduced AKT signaling shortens it. Effects of TOR-S6K appear to be mediated by SGG/GSK3β, a known kinase involved in clock regulation. Like SGG, TOR signaling affects the timing of nuclear accumulation of the circadian clock protein TIMELESS. Given that activities of AKT and TOR pathways are affected by nutrient/energy levels and endocrine signaling, these data suggest that metabolic disorders caused by nutrient and energy imbalance are associated with altered rest:activity behavior.

Results and Discussion

AKT and TOR Signaling Regulate Circadian Period

To address a role of metabolic pathways in the control of behavioral rhythms, we manipulated the activity of the well-known nutrient-sensing pathway, which includes AKT/PKB and TOR (target of rapamycin), in the central pacemaker cells. We first assayed for a possible function of AKT by overexpressing an active form of AKT, myr-AKT [5], in the Drosophila central pacemaker cells using the Pdf-Gal4 driver. The Pdf (pigment-dispersing factor) gene encodes a neuropeptide that is expressed in the ventral lateral neurons (LNvs), which are essential for maintenance of rest:activity rhythms in free-running conditions [6]. As shown in Table 1, expression of active AKT in the LNvs results in a longer circadian period of the rest:activity rhythm in a dose-dependent manner: whereas one copy of Pdf-Gal4 produced a small effect, two copies of Pdf-Gal4 resulted in a period of ~25 hr. A similar period lengthening was observed when myr-Akt was driven by one copy of Pdf-Gal4 in flies that have reduced expression of PTEN, a phosphatase that negatively regulates AKT activation.

Table 1.

AKT and TOR-S6K Activities Regulate Circadian Behavior

| Genotype | n (% R) | Period ± SEM | FFT ± SEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+ | 75 (100) | 24.15 ± 0.04 | 0.15 ± 0.005 |

| yw/Y; UAS-myrAkt/+ | 69 (94) | 23.77 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.005 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; UAS-myrAkt/+ | 50 (100) | 24.29 ± 0.04* | 0.11 ± 0.006 |

| yw/Y; Pten117/+; Pdf-G/+ | 16 (88) | 24.00 ± 0.08 | 0.03 ± 0.006 |

| yw/Y; Pten117/+; Pdf-G/UAS-myrAkt | 16 (100) | 24.98 ± 0.06* | 0.11 ± 0.011 |

| w/Y | 15 (100) | 23.57 ± 0.07 | 0.16 ± 0.009 |

| w/Y; Akt3/Akt04226 | 34 (100) | 23.19 ± 0.06* | 0.17 ± 0.008 |

| yw/Y; Akt04226 | 16 (100) | 23.23 ± 0.06* | 0.18 ± 0.013 |

| w/Y; Akt1/Akt04226 | 41 (100) | 23.15 ± 0.05* | 0.15 ± 0.009 |

| yw/Y; Pten117; Akt3 | 30 (79) | 24.14 ± 0.09 | 0.06 ± 0.009 |

| w/Y; Sine03756 | 30 (100) | 23.50 ± 0.07 | 0.06 ± 0.006 |

| w/Y; Sine03756; Pdf-G/UAS-Rheb#1 | 23 (100) | 25.09 ± 0.05* | 0.09 ± 0.007 |

| yw/Y;; UAS-Rheb#1/+ | 14 (100) | 24.02 ± 0.09 | 0.08 ± 0.008 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; UAS-Rheb#1/+ | 29 (94) | 25.24 ± 0.11* | 0.12 ± 0.01 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; gig109/+ | 50 (96) | 24.41 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.005 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; gig109/UAS-Rheb#1 | 32 (100) | 25.84 ± 0.07* | 0.18 ± 0.007 |

| yw/Y; UAS-Tor/+ | 32 (100) | 23.89 ± 0.05 | 0.09 ± 0.005 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/UAS-Tor | 16 (100) | 25.63 ± 0.10* | 0.19 ± 0.007 |

| yw/Y; UAS-Rheb#3/+; UAS-myrAkt/+ | 28 (100) | 23.67 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.008 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; Pdf-G/+ | 59 (100) | 24.04 ± 0.05 | 0.10 ± 0.008 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/UAS-Rheb#3; Pdf-G/+ | 62 (100) | 25.24 ± 0.07* | 0.13 ± 0.006 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; Pdf-G/UAS-myrAkt | 47 (100) | 24.94 ± 0.06* | 0.12 ± 0.010 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/UAS-Rheb#3; Pdf-G/UAS-myrAkt | 31 (100) | 25.95 ± 0.02* | 0.11 ± 0.001 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; gig109/UAS-myrAkt | 16 (100) | 24.71 ± 0.11* | 0.08 ± 0.011 |

| yw/Y;; UAS-S6kSTDE/+ | 58 (97) | 24.06 ± 0.05 | 0.08 ± 0.06 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; UAS-S6kSTDE/+ | 54 (87) | 24.39 ± 0.05* | 0.09 ± 0.009 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; Pdf-G/UAS-S6kSTDE | 48 (100) | 24.88 ± 0.06* | 0.06 ± 0.004 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; UAS-S6kSTDE/gig109 | 23 (100) | 24.98 ± 0.10* | 0.05 ± 0.007 |

| sggG0263/yw; Pdf-G/+ | 13 (81) | 24.45 ± 0.10 | 0.12 ± 0.016 |

| sggM11/yw; Pdf-G/+ | 19 (66) | 24.53 ± 0.11 | 0.06 ± 0.012 |

| sggD127/yw; Pdf-G/+ | 29 (71) | 24.81 ± 0.12 | 0.08 ± 0.012 |

| sggG0263/yw; Pdf-G/UAS-S6kSTDE | 18 (90) | 28.32 ± 0.22* | 0.03 ± 0.004 |

| sggM11/yw; Pdf-G/UAS-S6kSTDE | 31 (97) | 27.51 ± 0.09* | 0.03 ± 0.003 |

| sggD127/yw; Pdf-G/UAS-S6kSTDE | 14 (93) | 27.73 ± 0.18* | 0.03 ± 0.005 |

Pdf-G denotes Pdf-Gal4; % R denotes the percentage rhythmic based on χ2 periodogram analysis; SEM denotes standard error of the mean. FFT values represent the strength of the circadian rhythms. Asterisks denote significant difference (p < 0.05) when compared to sibling controls (one-way ANOVA when there are two sibling controls, Student's t test when only two genotypes are compared).

Due to the early embryonic lethality caused by a null mutation in Akt, we were not able to determine the effect of complete loss of AKT on circadian rhythms. However, hypomorphic Akt mutants (with about 30% AKT remaining) are viable as adults [5], so we used these mutants to test whether reduced AKT activity produces a phenotype opposite to that of AKT overexpression. As predicted, we found that Akt hypomorphic mutants have a shorter circadian period. Furthermore, this phenotype can be reversed by loss of PTEN. As shown in Table 1, double mutants of Pten117 and the hypomorphic Akt3 allele have a slightly longer circadian period and weakened circadian rhythms (as reflected in the reduced number of rhythmic flies and in smaller fast Fourier transform [FFT] values). These data indicate that regulated insulin-AKT signaling is required to maintain a normal circadian rhythm.

AKT not only regulates cellular metabolism and cell growth through its action in the insulin-signaling pathway, but it also interacts with the nutrient-sensing TOR pathway by phosphorylating TOR. Moreover, it phosphorylates the TOR inhibitor, tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) [7, 8], although it was recently found that AKT phosphorylation of TSC is not necessary for cell growth [9]. On the other hand, TOR signaling acts on AKT directly or through a feedback mechanism (see below). Thus, it is possible that AKT and TOR act in the same pathway to regulate circadian clock function. To test a role of TOR, we first increased TOR activity in the LNvs, by overexpressing either Tor [10] or the proto-oncogene Rheb, an upstream activator of TOR [11, 12], under the control of Pdf-Gal4. Overexpression of either transgene lengthened circadian period (Table 1), demonstrating that TOR activity regulates the circadian clock.

We next attempted to identify the TOR complex relevant for the control of circadian period. TOR is known to exist as two distinct complexes, TORC1 and TORC2; whereas TORC1 acts on ribosomal S6 kinase (S6K) [11], TORC2 acts on AKT through SIN1 in mammals [13, 14]. The effect of RHEB on circadian period suggested that TORC1 is the relevant complex, because RHEB is known to only activate TORC1, and not TORC2 [15]. Consistent with this idea, we found that a mutation in Sin1 does not affect circadian period and that overexpression of Rheb produces a long period in a Sin1 mutant background (Table 1). These findings confirm that TORC2 signaling is not a major player in circadian period regulation; instead, TORC1-S6K likely constitutes the clock-regulating pathway. To verify a role of S6K, we overexpressed its active form [16] in the LNvs. As with other manipulations that increased activity of the TORC1 pathway, we observed a lengthening of period (Table 1).

Although effects of TOR on the clock are not mediated by AKT, it is still possible that they act in the same pathway. As mentioned above, AKT activates TOR directly, or indirectly through deactivation of TSC. Coactivation of AKT and TOR in the same pathway could produce synergistic effects on downstream targets. However, coexpression of myr-AKT and RHEB in the central clock cells yielded an additive effect on circadian period (Table 1). Thus, although AKT may affect TOR activity, it is likely that they act in independent pathways to regulate circadian period. As described below, these pathways may converge on a common target.

Activity of the Tumor Suppressor TSC Is Required for Normal Circadian Behavior

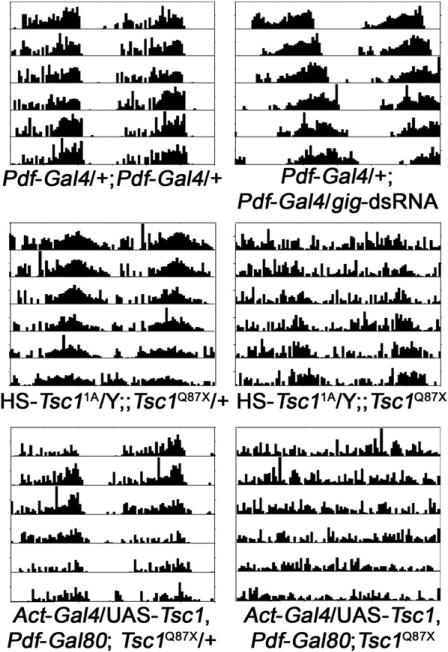

The tumor suppressor TSC is an inhibitor of TOR. It negatively regulates TOR activity by antagonizing the TOR activator RHEB (see review in [17]). Because overexpression of Rheb or S6k lengthens circadian period (Table 1), we speculated that this phenotype would be even stronger in a background sensitized by reduced TSC activity. Indeed, overexpression of Rheb or S6k in flies lacking one copy of Tsc2 (gig in Drosophila) resulted in an even longer circadian period. In addition, dsRNA-mediated knockdown of gig in central pacemaker cells lengthened circadian period (Figure 1 and Table 2). However, overexpression of both Tsc1 and Tsc2 did not cause period shortening (data not shown), perhaps because expression of TSC is normally saturating in clock cells.

Figure 1. Loss of TSC Activity Alters Circadian Behavior.

Flies expressing dsRNA against gig in the LNvs have lengthened circadian period (top panel). Leaky expression (without heat shock) of an HS-Tsc11A transgene rescues the developmental lethality caused by a Tsc1Q87X null mutation; however, these flies have longer circadian period and weaker rhythm strength (middle panel). When Tsc1 expression is rescued ubiquitously in a Tsc1Q87X null background (by Act-Gal4/UAS-Tsc1) [39] except in the LNvs (by Pdf-Gal80) [23], the result is arrhythmic circadian behavior (lower panel).

Table 2.

Circadian Behavior Characterization of Tsc Mutants

| Genotype | n (% R) | Period ± SEM | FFT ± SEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; Pdf-G/+ | 48 (100) | 23.99 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.02 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; Pdf-G/gig-dsRNA-2 | 45 (100) | 25.32 ± 0.09* | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; Pdf-G/gig-dsRNA-8 | 37 (100) | 25.24 ± 0.06* | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; gig109/+ | 50 (96) | 24.41 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.005 |

| yw/Y;; gig-dsRNA-8/+ | 10 (100) | 24.07 ± 0.17 | 0.13 ± 0.02 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/+; gig109/gig-dsRNA-8 | 31 (100) | 25.14 ± 0.05* | 0.05 ± 0.006 |

| yw/Y; gig-dsRNA-2/+; gig-dsRNA-8/+ | 9 (100) | 23.85 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 |

| yw/Y; Pdf-G/gig-dsRNA-2; gig109/gig-dsRNA-8 | 15 (100) | 25.87 ± 0.07* | 0.05 ± 0.008 |

| yw/Y; TG/+ | 46 (100) | 24.15 ± 0.06 | 0.11 ± 0.006 |

| yw/Y; TG/+; gig-dsRNA-8/+ | 29 (48) | 25.03 ± 0.21* | 0.04 ± 0.007 |

| yw, HS-Tsc11A/Y;; Tsc1Q87X/+ | 36 (92) | 23.39 ± 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.03 |

| yw, HS-Tsc11A/Y;; Tsc1Q87X | 36 (75) | 24.78 ± 0.13* | 0.03 ± 0.003 |

| yw, HS-Tsc11A/Y;; Tsc1Q87X/Tsc129 | 25 (88) | 24.70 ± 0.14* | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| yw/Y; HS-Tsc12B/+; Tsc1Q87X/+ | 24 (96) | 23.83 ± 0.08 | 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| yw/Y; HS-Tsc12B/+; Tsc1Q87X/Tsc129 | 22 (15) | 24.29 ± 0.09* | 0.01 ± 0.005 |

| yw/Y; Act-G/UAS- Tsc1, Pdf-Gal80; Tsc1Q87X/+ | 49 (92) | 24.02 ± 0.07 | 0.04 ± 0.004 |

| yw/Y; Act-G/UAS- Tsc1, Pdf-Gal80; Tsc1Q87X | 18 (0) | ||

| yw/Y; UAS-Tsc1, Pdf-Gal80/+; Tsc129/+ | 32 (100) | 24.07 ± 0.09 | 0.12 ± 0.007 |

| w/Y; Act-G/UAS-Tsc1, Pdf-Gal80; Tsc129/Tsc1Q87X | 43 (35) | 23.98 ± 0.10 | 0.05 ± 0.007 |

Pdf-G denotes Pdf-Gal4; Act-G denotes Act-Gal4; TG denotes tim-Gal4; HS-Tsc1 denotes heat-shock promoter-Tsc1 transgene. Leaky expression of HS-Tsc11A (without heat-shock treatment) was able to rescue lethality caused by Tsc1Q87X mutation. HS-Tsc12B transgene rescued lethality of Tsc1 mutation only when treated with daily heat shock. gig-dsRNA lines were obtained from NIG-BIO (Japan). Asterisks denote significant difference (p < 0.05) when compared to sibling controls (one-way ANOVA when there are two sibling controls, Student's t test when only two genotypes are compared).

Because loss of either the Tsc1 or Tsc2 gene of TSC causes early larval lethality, we were not able to examine the circadian phenotype of these null mutants. To circumvent this, we used a heat-shock promoter (HS)-driven Tsc1 transgene to rescue null Tsc1Q87X mutants through development, and then assessed adult circadian behavior. Leaky expression of the HS-Tsc11A transgene was able to rescue the lethality of Tsc1Q87X without a high-temperature heat shock. As shown in Figure 1, most of these flies are weakly rhythmic, and have a longer circadian period. In addition, we found that a second transgene (HS-Tsc12B) only rescued the developmental lethality caused by Tsc1Q87X if daily heat-shock treatment was provided during development. Consistent with the reduced expression of this transgene, the majority of the rescued flies are arrhythmic. Interestingly, the circadian periods of the rhythmic flies are not longer than the ones rescued by leaky expression of HS-Tsc11A. Furthermore, we generated flies that lack Tsc1 only in central clock cells by rescuing Tsc1 in all cells (through Act-Gal4/UAS-Tsc1) except the central clock cells (blocked by Pdf-Gal80). Most of these flies are arrhythmic (Figure 1 and Table 2) and, as above, those that are rhythmic do not have longer circadian periods. One possible explanation of the normal period is that elevated S6K activity in TSC mutant clock cells feeds back to downregulate AKT activity [18]. Nonetheless, this deregulated TOR-S6K activity destabilizes the overall rhythm. These data indicate that TSC is not only required to keep the circadian period close to 24 hr, but is also necessary for the maintenance of robust circadian rhythms.

AKT and TOR-S6K Signaling Converge on GSK3β/SGG

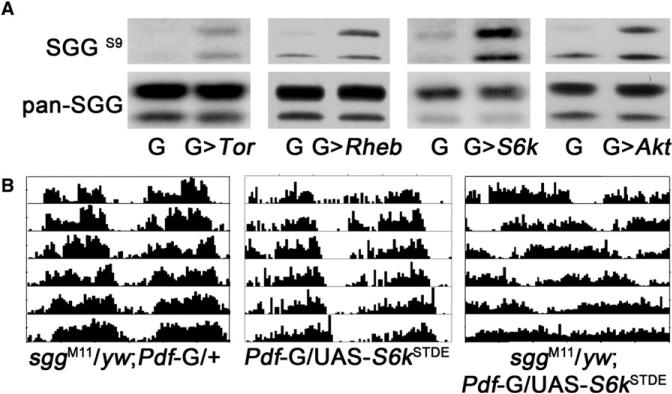

It is well known that AKT negatively regulates GSK3β through phosphorylation in mammals, and this mechanism is conserved in Drosophila [19] (Figure 2). Meanwhile, S6K can also negatively regulate GSK3β activity [18]. In TSC knockout mouse embryonic fibroblast cells, S6K kinase activity is highly upregulated, resulting in increased GSK3β phosphorylation and thus decreased activity [18]. Thus, both AKT and S6K regulate GSK3β, which may be the point at which they converge on the circadian clock, because GSK3β phosphorylates clock proteins [20–22]. We found that TOR-S6K regulation of GSK is conserved in Drosophila: as shown in Figure 2, elevated TOR-S6K activity leads to increased phosphorylation of SGG (Drosophila homolog of GSK3β) at the Ser9 residue. Consistent with this observation, we found that elevated S6K activity has a stronger effect on circadian period in an sgg heterozygous mutant background (Figure 3), indicating that increased S6K and reduced SGG have synergistic effects on circadian period. These data suggest that the effect of increased AKT and TOR-S6K signaling on the circadian clock is mediated by SGG.

Figure 2. Elevated TOR-S6K and Reduced Expression of SGG Synergistically Affect the Circadian Clock.

(A) GMR-Gal4-driven expression of either UAS-Tor, UAS-Rheb, UAS-S6kSTDE, or UAS-myrAkt increases phosphorylation of SGG at the Ser9 residue. Samples were collected at ZT8.

(B) Overexpression of S6k in the LNvs in an sggM11 heterozygote background lengthens circadian period more than predicted by an additive effect, indicating synergistic interaction between S6K and SGG.

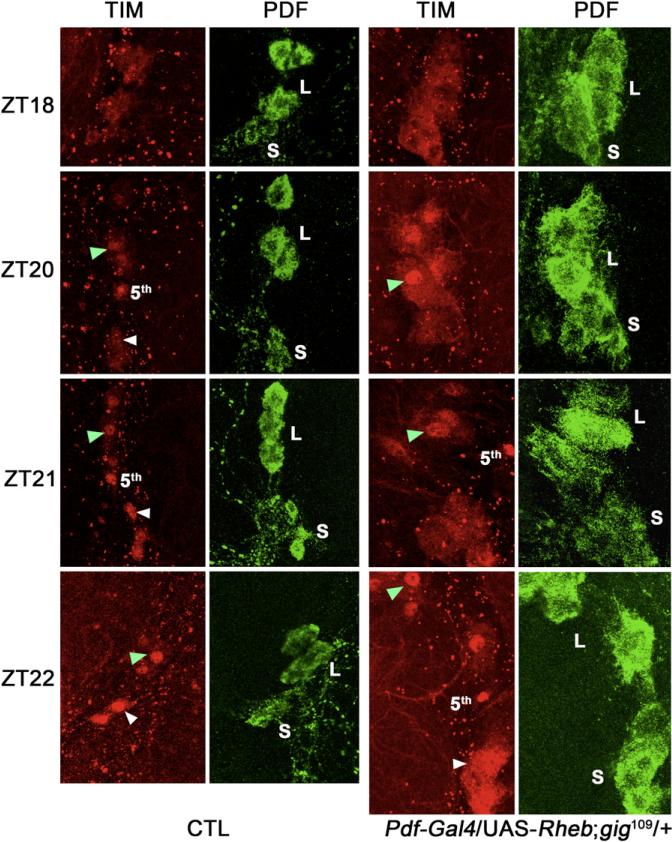

Figure 3. Nuclear Accumulation of TIM Protein Is Delayed in s-LNvs that Have Elevated TOR Signaling.

In wild-type flies, TIM expression is predominantly in the cytoplasm at ZT18; it starts entering the nucleus around ZT20, and most of the TIM protein is in the nucleus at ZT21. In contrast, when UAS-Rheb is driven by Pdf-Gal4 in flies lacking one copy of Tsc2 (gig109 heterozygous background), nuclear accumulation of TIM in the s-LNvs is delayed about 2 hr, such that at ZT22, TIM protein is still distributed evenly between cytoplasm and nucleus. However, this delay is only observed in the s-LNvs: TIM enters the nucleus around ZT20 in both wild-type and mutant l-LNvs. Nuclear accumulation is indicated by arrowheads (green for l-LNvs, white for s-LNvs). The fifth LNv that does not express PDF is marked. Representative images of ten brain hemispheres of each time point are shown. L denotes l-LNvs; S denotes s-LNvs.

Elevated TOR Signaling Delays the Nuclear Accumulation of TIMELESS

SGG activity regulates circadian period through the circadian clock protein TIMELESS (TIM). It was previously reported that SGG directly phosphorylates TIM, and affects the timing of nuclear expression of TIM and its partner protein, PERIOD (PER) [22]. To test whether increased TOR signaling also regulates nuclear accumulation of TIM in the central pacemaker cells, we examined the expression of TIM in the second half of the night. As shown in Figure 3, TIM nuclear accumulation is delayed in small ventral lateral neurons (s-LNvs) that have elevated TOR signaling. Intriguingly, nuclear accumulation of TIM in the large ventral lateral neurons (l-LNvs) is not affected by elevated TOR activity. One possible explanation is that l-LNvs are insensitive to SGG activity, because it was reported earlier that circadian oscillations of tim RNA in l-LNvs are not affected by overexpression of SGG (Pdf-Gal4/UAS-sgg), in contrast to the phase advance observed in the s-LNvs [23]. The mechanism underlying this differential regulation is unclear.

Taken together, we have identified a role for genes important for nutrient and energy metabolism in regulating circadian clock function in the central brain. The AKT and TSC-TOR-S6K pathways receive multiple inputs regarding nutrient influx, endocrine signaling, and cellular energy balance. Mammalian studies have shown that disruption of energy metabolism affects circadian gene expression in peripheral tissues and, under some conditions, even has effects in some areas of the brain. For instance, restricted feeding entrains the peripheral clock in the liver but not the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) [24, 25], although recently the lack of any effect on the SCN has been questioned. Thus, timed hypocaloric conditions induce a phase advance of locomotor activity rhythms, suggesting an involvement of the SCN clock [26]. High-fat diet also affects circadian clock gene expression in peripheral tissues [27, 28]. In addition, high-fat-diet-induced and genetically obese mice both have altered expression of circadian clock genes in the brainstem [4]. Importantly, a high-fat diet lengthens the circadian period of behavioral rhythms in mammals [27]. These observations suggest that nutrient and energy metabolism impact the circadian clock; the question is how these different metabolic parameters affect circadian clock function.

There are several possible mechanisms by which nutrient and energy metabolism could affect peripheral clocks. Local physiological factors dependent on metabolic activity could influence the expression of core clock components and of nuclear receptors that regulate clock gene expression. Indeed, cellular redox state [29], AMPK activity [30, 31], NAD+ levels, and SIRT1 activities [32–34] appear to feed into the circadian clock in peripheral tissues such as the liver. AMPK, which acts upstream of TSC in mammals, directly phosphorylates Cryptochrome in peripheral tissues [30]. However, prior to this work, there was no known mechanism for the modulation of the central pacemaker by nutrient-sensing pathways. Our study identifies such a mechanism by demonstrating that metabolic genes such as AKT and TOR-S6K act in the central pacemaker cells in the brain. The lengthened circadian period caused by high-fat diet in mammals is likely mediated by these molecules. This conclusion is further supported by a recent cell-culture-based genome-wide RNAi study that implicated the PI3K-TOR pathway in the regulation of circadian period [35]. In addition, another ribosomal S6 kinase (S6KII) was found to influence the circadian clock through its interaction with casein kinase 2β [36]. Importantly, daily fasting:feeding cycles driven by the central clock regulate circadian gene transcription in the liver [37], whereas clock function in the liver contributes to energy homeostasis [38]. We speculate that metabolic stress or energy imbalance affects AKT and TOR-S6K signaling, resulting in general circadian disruption, which in turn exacerbates metabolic deregulation and, consequently, facilitates the development of metabolic syndromes prevalent in modern society.

Experimental Procedures

Circadian Behavioral Assay

All fly stocks were raised on standard molasses-yeast-corn meals in a 25° C incubator except that of the heat-shock rescue experiment as noted. Three- to five-day-old adult flies were collected and entrained to a 12 hr:12 hr light:- dark cycle at 25° C for 3 days. Individual flies were loaded into locomotor tubes containing 5% sucrose and locomotor activity was recorded under constant darkness conditions for more than 7 days. Activity records were analyzed by using Clocklab software (Actimetrics). Circadian periodicity was evaluated by using χ2 periodogram analysis. FFT analysis was used to determine the strength of the rhythm for a specified circadian period. OriginPro8.1 (OriginLab) was used for statistical analysis of circadian period. Student's t tests were performed when only two genotypes were involved, and one-way ANOVA was performed when more than three genotypes were compared.

Transgenic Flies

Coding sequence of Tsc1 was PCR amplified and inserted into the Drosophila transformation vector pCasPeR-HS at the BglII and NotI restriction sites. Germline transformation was performed by Rainbow Transgenic Services. Two independent insertions were used to rescue the developmental lethality of Tsc1Q87X by daily heat-shock treatment at 37° C (three times, 30 min each) from the first instar stage onward.

Western-Blot Analysis

Three- to five-day-old adult flies were entrained to 12 hr:12 hr light:dark cycles for 3 days and heads were collected at Zeitgeber time (ZT) 8. Fly heads were homogenized in cell lysis buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10 mM HEPES, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5 mM DTT, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), along with the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid. Head lysates were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel, which was blotted to nitrocellulose membrane after electrophoresis. Primary antibodies mouse anti-phospho-SGG and total SGG were used at 1/500 and 1/10,000 dilution, respectively. After overnight incubation at 4° C, blots were washed in PBS-Tween 20 and incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), followed by three 20 min washes in PBS-Tween 20. After enhanced chemiluminescence, blots were exposed to X-ray film.

Immunohistochemistry and Confocal Microscopy

Fly brains were dissected out in 4% PFA solution at indicated time points, washed for 1 hr in PBS-Triton X-100 buffer, and incubated with primary antibody (in PBS buffer with 3% normal donkey serum and 0.3% Triton X-100) overnight at 4° C. They were then washed three times for 20 min each with PBS buffer and incubated with Cy3 donkey anti-rat and FITC donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 1.5 hr at room temperature, followed by extensive washes in PBS-Triton X-100. Primary antibodies rat anti-TIM and rabbit anti-PDF were used at 1:1000 dilution. Images were taken using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mallory Sowcik, Dechun Chen, and Zhifeng Yue for their technical support. We are grateful to Ernst Hafen (University of Zürich, Switzerland), Bruce Edgar (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle), Duojia Pan (Johns Hopkins University), Morris Birnbaum (University of Pennsylvania), Michael Rosbash (Brandeis University), the Bloomington Stock Center and NIG-BIO (Japan) for providing fly stocks, and Marc Bourouis (Université de Nice, France) for providing SGG antibodies. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 NS-048471. A.S. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Kohsaka A, Bass J. A sense of time: How molecular clocks organize metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;18:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staels B. When the Clock stops ticking, metabolic syndrome explodes. Nat. Med. 2006;12:54–55. doi: 10.1038/nm0106-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando H, Takamura T, Matsuzawa-Nagata N, Shima K, Eto T, Misu H, Shiramoto M, Tsuru T, Irie S, Fujimura A, et al. Clock gene expression in peripheral leucocytes of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52:329–335. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaneko K, Yamada T, Tsukita S, Takahashi K, Ishigaki Y, Oka Y, Katagiri H. Obesity alters circadian expressions of molecular clock genes in the brainstem. Brain Res. 2009;1263:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stocker H, Andjelkovic M, Oldham S, Laffargue M, Wymann MP, Hemmings BA, Hafen E. Living with lethal PIP3 levels: viability of flies lacking PTEN restored by a PH domain mutation in Akt/PKB. Science. 2002;295:2088–2091. doi: 10.1126/science.1068094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renn SCP, Park JH, Rosbash M, Hall JC, Taghert PH. A pdf neuropeptide gene mutation and ablation of PDF neurons each cause severe abnormalities of behavioral circadian rhythms in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;99:791–802. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potter CJ, Pedraza LG, Xu T. Akt regulates growth by directly phosphorylating Tsc2. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:658–665. doi: 10.1038/ncb840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navé BT, Ouwens DM, Withers DJ, Alessi DR, Shepherd PR. Mammalian target of rapamycin is a direct target for protein kinase B: identification of a convergence point for opposing effects of insulin and amino-acid deficiency on protein translation. Biochem. J. 1999;344:427–431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong J, Pan D. Tsc2 is not a critical target of Akt during normal Drosophila development. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2479–2484. doi: 10.1101/gad.1240504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hennig KM, Neufeld TP. Inhibition of cellular growth and proliferation by dTOR overexpression in Drosophila. Genesis. 2002;34:107–110. doi: 10.1002/gene.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stocker H, Radimerski T, Schindelholz B, Wittwer F, Belawat P, Daram P, Breuer S, Thomas G, Hafen E. Rheb is an essential regulator of S6K in controlling cell growth in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:559–566. doi: 10.1038/ncb995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saucedo LJ, Gao X, Chiarelli DA, Li L, Pan D, Edgar BA. Rheb promotes cell growth as a component of the insulin/TOR signalling network. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:566–571. doi: 10.1038/ncb996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Q, Inoki K, Ikenoue T, Guan KL. Identification of Sin1 as an essential TORC2 component required for complex formation and kinase activity. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2820–2832. doi: 10.1101/gad.1461206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frias MA, Thoreen CC, Jaffe JD, Schroder W, Sculley T, Carr SA, Sabatini DM. mSin1 is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation, and its isoforms define three distinct mTORC2s. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1865–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Q, Inoki K, Kim E, Guan K-L. TSC1/TSC2 and Rheb have different effects on TORC1 and TORC2 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:6811–6816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602282103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barcelo H, Stewart MJ. Altering Drosophila S6 kinase activity is consistent with a role for S6 kinase in growth. Genesis. 2002;34:83–85. doi: 10.1002/gene.10132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwiatkowski DJ, Manning BD. Tuberous sclerosis: a GAP at the crossroads of multiple signaling pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:R251–R258. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang HH, Lipovsky AI, Dibble CC, Sahin M, Manning BD. S6K1 regulates GSK3 under conditions of mTOR-dependent feedback inhibition of Akt. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papadopoulou D, Bianchi MW, Bourouis M. Functional studies of shaggy/glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation sites in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:4909–4919. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4909-4919.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin L, Wang J, Klein PS, Lazar MA. Nuclear receptor Rev-erb{alpha} is a critical lithium-sensitive component of the circadian clock. Science. 2006;311:1002–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1121613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iitaka C, Miyazaki K, Akaike T, Ishida N. A role for glycogen synthase kinase-3β in the mammalian circadian clock. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:29397–29402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinek S, Inonog S, Manoukian AS, Young MW. A role for the segment polarity gene shaggy/GSK-3 in the Drosophila circadian clock. Cell. 2001;105:769–779. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoleru D, Peng Y, Nawathean P, Rosbash M. A resetting signal between Drosophila pacemakers synchronizes morning and evening activity. Nature. 2005;438:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature04192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damiola F, Le Minh N, Preitner N, Kornmann B, Fleury-Olela F, Schibler U. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2950–2961. doi: 10.1101/gad.183500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hara R, Wan K, Wakamatsu H, Aida R, Moriya T, Akiyama M, Shibata S. Restricted feeding entrains liver clock without participation of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Cells. 2001;6:269–278. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Challet E, Takahashi JS, Turek FW. Nonphotic phase-shifting in Clock mutant mice. Brain Res. 2000;859:398–403. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohsaka A, Laposky AD, Ramsey KM, Estrada C, Joshu C, Kobayashi Y, Turek FW, Bass J. High-fat diet disrupts behavioral and molecular circadian rhythms in mice. Cell Metab. 2007;6:414–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnea M, Madar Z, Froy O. High-fat diet delays and fasting advances the circadian expression of adiponectin signaling components in mouse liver. Endocrinology. 2009;150:161–168. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rutter J, Reick M, Wu LC, McKnight SL. Regulation of Clock and NPAS2 DNA binding by the redox state of NAD cofactors. Science. 2001;293:510–514. doi: 10.1126/science.1060698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamia KA, Sachdeva UM, DiTacchio L, Williams EC, Alvarez JG, Egan DF, Vasquez DS, Juguilon H, Panda S, Shaw RJ, et al. AMPK regulates the circadian clock by Cryptochrome phosphorylation and degradation. Science. 2009;326:437–440. doi: 10.1126/science.1172156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vieira E, Nilsson EC, Nerstedt A, Ormestad M, Long YC, Garcia-Roves PM, Zierath JR, Mahlapuu M. Relationship between AMPK and the transcriptional balance of clock-related genes in skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;295:E1032–E1037. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90510.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asher G, Gatfield D, Stratmann M, Reinke H, Dibner C, Kreppel F, Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW, Schibler U. SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation. Cell. 2008;134:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakahata Y, Kaluzova M, Grimaldi B, Sahar S, Hirayama J, Chen D, Guarente LP, Sassone-Corsi P. The NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 modulates CLOCK-mediated chromatin remodeling and circadian control. Cell. 2008;134:329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramsey KM, Yoshino J, Brace CS, Abrassart D, Kobayashi Y, Marcheva B, Hong H-K, Chong JL, Buhr ED, Lee C, et al. Circadian clock feedback cycle through NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis. Science. 2009;324:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1171641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang EE, Liu AC, Hirota T, Miraglia LJ, Welch G, Pongsawakul PY, Liu X, Atwood A, Huss Iii JW, Janes J, et al. A genome-wide RNAi screen for modifiers of the circadian clock in human cells. Cell. 2009;139:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akten B, Tangredi MM, Jauch E, Roberts MA, Ng F, Raabe T, Jackson FR. Ribosomal S6 kinase cooperates with casein kinase 2 to modulate the Drosophila circadian molecular oscillator. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:466–475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4034-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vollmers C, Gill S, DiTacchio L, Pulivarthy SR, Le HD, Panda S. Time of feeding and the intrinsic circadian clock drive rhythms in hepatic gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:21453–21458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909591106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamia KA, Storch K-F, Weitz CJ. Physiological significance of a peripheral tissue circadian clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:15172–15177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao X, Pan D. TSC1 and TSC2 tumor suppressors antagonize insulin signaling in cell growth. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1383–1392. doi: 10.1101/gad.901101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]