Abstract

Zwittermicin A (ZmA) is a hybrid polyketide-nonribosomal peptide produced by certain Bacillus cereus group strains. It displays broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Its biosynthetic pathway in B. cereus has been proposed through analysis of the nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) and polyketide synthase (PKS) modules involved in ZmA biosynthesis. In this study, we constructed a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki strain YBT-1520 genomic DNA. The presence of known genes involved in the biosynthesis of ZmA in this BAC library was investigated by PCR techniques. Nine positive clones were identified, two of which (covering an approximately 60-kb region) could confer ZmA biosynthesis ability upon B. thuringiensis BMB171 after simultaneous transfer into this host by two compatible shuttle BAC vectors. Another previously unidentified gene cluster, named zmaWXY, was found to improve the yield of ZmA and was experimentally defined to function as a ZmA resistance transporter which expels ZmA from the cells. Putative transposase genes were detected on the flanking regions of the two gene clusters (the ZmA synthetic cluster and zmaWXY), which suggests a mobile nature of these two gene clusters. The intact ZmA gene cluster was validated, and a resistance mechanism complementary to that for zmaR (the previously identified ZmA self-resistance gene) was revealed. This study also provided a straightforward strategy to isolate and identify a huge gene cluster from Bacillus.

INTRODUCTION

Zwittermicin A (ZmA) was first discovered in culture supernatants of Bacillus cereus strain UW85, which has the ability to suppress plant disease (11). ZmA has a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, inhibiting certain Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and eukaryotic microorganisms (32). It also has the ability to potentiate the insecticidal activity of the protein toxins produced by Bacillus thuringiensis (3). ZmA is a linear aminopolyol and represents a new structural class of antibiotic (12). Its unusual structure and diverse biological activities prompted investigation of its biosynthesis.

The ZmA self-resistance gene (zmaR) was first isolated from B. cereus UW85 by Handelsman's group (23). zmaR encodes an acetyltransferase, which acetylates ZmA, rendering it inactive (34). Insertional inactivation of zmaR in strain UW85 demonstrated that zmaR is necessary for high-level resistance to ZmA but is not required for ZmA production (35).

A 16-kb DNA fragment (zma16Bc) from strain UW85, including nine genes and a partial gene (covering zmaR), has been isolated. The presence of genes encoding nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) and polyketide synthase (PKS) homologues in this fragment suggested that ZmA is synthesized by a mixed NRPS/PKS pathway (8). Handelsman's group proposed a model for the ZmA biosynthesis pathway and clearly showed that this 16-kb fragment does not contain all the genes necessary for the biosynthesis of ZmA, as some important genes required for the proposed pathway were missing.

Subsequently, our research group identified three new genes (zwa6, zwa5A, and zwa5B) from another ZmA-producing strain, B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki strain YBT-1520, by sequencing the region downstream of the zma16Bc cluster (38, 39). These three genes could fulfill the functions in Handelsman's proposed ZmA biosynthetic pathway, so they were predicted to take part in ZmA biosynthesis.

Recently, Thomas' group revealed a 62.5-kb region consisting of 22 open reading frames (ORFs) related to ZmA biosynthesis by mapping the zma16Bc cluster from B. cereus UW85. They predicted that ZmA is biosynthesized in an unusual manner that involves processing of both its N and C termini, potentially resulting in the production of two additional metabolites besides ZmA (18). The metabolite (acyl-d-Asn-ZmA) synthesized by the gene cluster is proposed to be cleaved by the secretion transporter ZmaM between the d-Asn and d-Ser, releasing ZmA and fatty acyl-d-Asn (metabolite A), and then they are exported out of the cell by ZmaM (18). One of the two putative additional metabolites (metabolite B) was subsequently detected by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (4). Until now, the proposed mechanism of ZmA biosynthesis has relied mainly on bioinformatics analysis, and no direct experiments have been performed to define whether this gene cluster is sufficient for ZmA biosynthesis.

Heterologous expression in related bacteria has been successfully employed to identify large gene clusters (2, 9, 17, 37). A 12-kb thuringiensin biosynthetic gene cluster from Bacillus has been identified in this way by us previously. Thuringiensin production could be observed when this 12-kb region was electroporated into a surrogate Bacillus host with the B. thuringiensis-Escherichia coli shuttle bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) vector pEMB0557, which confirms that this 12-kb region is sufficient for the thuringiensin production (20). With the discovery of increasing numbers of large gene clusters, the limitation of this approach is the restriction of the loading capacity of the vector and the transformation efficiency of the large recombinant plasmid in Bacillus. We have developed an improved electroporation protocol for Bacillus that efficiently transfers a recombinant plasmid with up to 40 kb of DNA inserted in the shuttle BAC vector pEMB0557 (19, 25).

In this study, we present a multiplasmid heterologous expression approach to validate the ZmA biosynthetic gene cluster. We constructed a BAC library with an average insert size of 45 kb from B. thuringiensis strain YBT-1520, whose genome sequencing is nearly complete. Nine BAC clones, whose DNA inserts are related to zma16Bc, were screened. Two of these clones were individually cloned into two compatible shuttle BAC vectors and transferred simultaneously into a ZmA-nonproducing strain, B. thuringiensis BMB171 (13). Several sets with different combinations of the nine BAC clones were also formed. Finally, two strains of B. thuringiensis BMB171 containing the recombinant plasmids did produce ZmA, with different yields. We demonstrated that a 60,235-bp region covered by two BAC clones is sufficient for ZmA biosynthesis. Furthermore, we also identified three new ORFs, zmaWXY, downstream of this 60-kb cluster, which function as a resistance transporter, forming a different self-resistance mechanism for a ZmA producer strain in addition to zmaR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

B. thuringiensis strain YBT-1520 was isolated from Chinese soil by our group and was shown to produce ZmA. B. cereus UW85 is the first strain found to produce ZmA. B. thuringiensis strain BMB171 is an acrystalliferous mutant strain and acted as a surrogate host in this study. Two compatible shuttle BAC vectors, pEMB0557 and pEMB0603, were constructed for cloning large fragments in Bacillus. The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Species and strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH10B | Δ(mrr hsdRMS mcrBC) mcrA recA1 | New England Biolabs |

| E. herbicola LS005 | Indicator strain for ZmA production | 31 |

| B. cereus UW85 | Produces ZmA | 31 |

| B. thuringiensis | ||

| YBT-1520 | B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki | 38 |

| BMB171 | Acrystalliferous mutant of B. thuringiensis | 13 |

| BMB1212 | BMB171 with plasmid pEMB1212, carrying zmaR | This study |

| BMB1236 | Mutant of strain YBT-1520 in which the orf123 gene was knocked out | This study |

| BMB1237 | BMB1236 with plasmid pEMB1237, in which the knocked-out orf123 gene was complemented | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBeloBAC11 | BAC cloning vector for E. coli | 21 |

| pHT304 | E. coli and B. thuringiensis shuttle vector | 1 |

| pHT304-ts | pHT304 derivative with a temp-sensitive Bacillus replicon; Ermr for B. thuringiensis | 20 |

| pDG780 | Vector with Kanr for B. thuringiensis | BGSC |

| pEMB0557 | E. coli-to-B. thuringiensis shuttle BAC vector; ori60, Ermr for B. thuringiensis | 19 |

| pEMB0603 | E. coli-to-B. thuringiensis shuttle BAC vector; ori44, Kanr for B. thuringiensis | This study |

| pEMB1212 | 1.2-kb PCR fragment containing zmaR cloned into pHT304 at SphI/BamHI sites | This study |

| pEMB1231 | 2.9-kb PCR fragment containing zmaWXY cloned into pHT304 at SphI/BamHI sites | This study |

| pEMB1232 | 33.7-kb 4B1 NotI fragment containing zmaR cloned into pEMB0603 at NotI site | This study |

| pEMB1236 | Interrupted orf123 gene cloned into pHT304-ts | This study |

| pEMB1237 | orf123 gene cloned into pHT304 | This study |

Kanr, kanamycin resistance; Ermr, erythromycin resistance.

E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C, while B. thuringiensis strains were grown at 28°C in 50% (wt/vol) tryptic soy broth (TSB) medium or LB medium. Ampicillin (100 μg/ml for E. coli), chloromycetin (12.5 μg/ml for E. coli), erythromycin (25 μg/ml for Bacillus), and kanamycin (50 μg/ml for Bacillus) were used in solid and liquid media for the propagation of plasmids.

DNA manipulation.

Established protocols for molecular biology techniques were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (29). Plasmid DNA was obtained from B. thuringiensis strains by the modified method of Andrup et al. (1). Oligonucleotides synthesis and DNA sequencing were carried out by Invitrogen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai).

Construction of a BAC library of B. thuringiensis strain YBT-1520.

It has proved difficult to transfer large recombinant plasmids into B. thuringiensis by electroporation (24, 36). Therefore, we developed a transformation procedure to effectively transfer up to 40-kb fragments into B. thuringiensis (19). A BAC library from B. thuringiensis strain YBT-1520 was constructed as previously described (21), with an average insert size of 45 kb. B. thuringiensis strain YBT-1520 was cultured for 5 h at 28°C in LB medium to a density of 3 × 108 cells/ml. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (10 min at 4°C and 12,000 × g), and agarose plugs were prepared. Genomic DNA embedded in the agarose plugs was partially digested with HindIII and then separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). High-molecular-weight genomic DNA was recovered and ligated into the BAC vector pBeloBAC11, which was previously digested with HindIII. The ligation mix was transformed into E. coli strain DH10B by electroporation with a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser. To estimate the insert sizes, the BAC recombinant plasmids were cleaved with NotI and then separated by PFGE with a Bio-Rad CHEF III instrument. The library consisted of 1,200 clones, with an insert size distribution ranging from 25 to 55 kb.

Transformation of large plasmids into B. thuringiensis.

Transformation of large plasmids into B. thuringiensis strain BMB171 was performed by electroporation with the Bio-Rad Gene Pulser set, as previously described (25).

ZmA production assays.

ZmA antibacterial activity was determined in an agar diffusion assay with Erwinia herbicola LS005 as the indicator on 10% (wt/vol) TSB agar plates (31). Culture supernatants of sporulated B. thuringiensis strains and their transformants were filtered with MF-Millipore filters (PES membrane, 0.22 μm) and then used to test their growth inhibition of E. herbicola LS005. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 28°C before scoring for the presence or absence of an inhibition zone. ZmA production was indicated by the presence of an inhibition zone. The diameter of the growth inhibition zone was measured, and the relative concentrations of ZmA in the supernatants were deduced by comparing the inhibition zone sizes of the test strains with the zone size of a ZmA producer strain.

For further identification of ZmA production, culture filtrates were further filtered with Biomax filters (Millipore; nominal molecular mass limit, 3 kDa). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) combined with ion trap/time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LC-MS–IT-TOF) (Shimadzu) was performed to detect ZmA by its molecular weight (m/z, 397 [MH+]). The separation was performed on a C18 column, using a gradient elution consisting of mobile phase A (0.1% [wt/vol] formic acid) and mobile phase B (acetonitrile-water [20:80, vol/vol]).

Insertional inactivation of gene orf123.

An 800-bp fragment and a 791-bp fragment, corresponding to the DNA regions upstream and downstream of the open reading frame of the orf123 gene in strain YBT-1520, respectively, were generated by PCR using the primer pairs F9/F10 and F11/F12 (Table 2) and digested with HindIII-SalI and BamHI-KpnI, respectively. A kanamycin resistance cassette (1,512 bp) was amplified with primer pairs F13/F14 (Table 2) from plasmid pDG780 and digested with SalI-BamHI. These three fragments were cloned into the temperature-sensitive plasmid pHT304-ts at HindIII-KpnI sites. The resulting plasmid, pEMB1236, was transformed into strain YBT-1520 by electroporation. The transformant was cultivated in LB medium with kanamycin added for 8 h. The transformant was then cultivated at 45°C for 4 days to eliminate the unintegrated temperature-sensitive plasmid pEMB1236. Kanamycin-resistant but erythromycin-sensitive colonies were harvested. The colonies with allelic double exchange were confirmed by PCR, and the correct mutant strain was named BMB1236.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea (5′ to 3′) | Product size (bp) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | CCAGGTCTCAGAAGGAGTAA | 671 | Probe for screening YBT-1520 BAC library |

| F2 | TGCATCAGAACCAACCTCTG | ||

| F3 | ATTGGCAAGAGGTGGGTATGTCACTT | 1005 | Probe for screening YBT-1520 BAC library |

| F4 | TAGCATATCGAACATGGTGCGGTTCT | ||

| F5 | ATTGCATGCATTTGCCATACCATCCACTAAG | 2878 | For amplifying the zmaWXY genes from YBT-1520 |

| F6 | ATTGGATCCTTCTCCGATCCCAATTTTCC | ||

| F7 | ATTGCATGCACTTGTTCTCAAAAGGGAGG | 1241 | For amplifying the zmaR gene from YBT-1520 |

| F8 | ATTGGATCCGAATAATGGGATCCTACGCC | ||

| F9 | GGAAAGCTTGGTATTCAGCGTGCTCATTC | 800 | For amplifying the upstream of gene orf123 from YBT-1520 |

| F10 | GGAGTCGACAATGATTAGTCGTGTTTACCG | ||

| F11 | GGAGGATCCGTATCTGAGCTTAGTGATGG | 791 | For amplifying the downstream of gene orf123 from YBT-1520 |

| F12 | GGAGGTACCCATCCGATAACAAACCTCTC | ||

| F13 | GGAGTCGACATTCGATATCAAGCTTATCG | 1512 | For amplifying the kanamycin resistance cassette from pDG780 |

| F14 | GGAGGATCCCGGTATCGATACAAATTCCT | ||

| F15 | TAAGAATTCTTGGGAAGAAGTCTGTCGTG | 1396 | For amplifying the gene orf123 from strain YBT-1520 |

| F16 | TCCGAATTCGCTTATGTAATCTCCTAATTC |

Restriction sites within the PCR primers are underlined.

Gene orf123 was amplified by primer pair F15/F16 (Table 2). The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and then inserted into the EcoRI site of shuttle vector pHT304 to create recombinant plasmid pEMB1237. pEMB1237 was then introduced into strain BMB1236, generating BMB1237, to complement the orf123 mutation. The vector pHT304 was introduced into strain BMB1236 as a negative control.

ZmA sensitivity test.

The ZmA sensitivities of B. thuringiensis strain BMB171 and other stains were determined in agar diffusion tests. One hundred microliters of stationary-phase culture was inoculated into 5 ml of TSB medium and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8. Two hundred microliters of a 10−2 dilution was spread on a 10% (wt/vol) TSB agar plate. Various amounts of ZmA which were HPLC purified (in a volume of 100 μl) were added to Oxford cups (8-mm diameter) on the test plate. The plate was kept for 2 h at 4°C for diffusion and then incubated overnight at 28°C. The diameter of the growth inhibition zone was measured. ZmA sensitivity was indicated by the size of the inhibition zone.

LC-MS–IT-TOF assay for acetylated ZmA in intracellular contents.

The test stains were grown in 100 ml LB medium at 28°C until the cell density reached an OD600 of 0.3. ZmA was then added to the cultures at final concentrations of 30 μg/ml or 150 μg/ml. The cultures were then incubated at 28°C until the OD600 reached 0.8. The cells were harvested and washed three times with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The cells were then quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and adequately triturated. After centrifugation (10 min at 2°C and 12,000 × g), the supernatants were collected and LC-MS–IT-TOF was used to detect the molecular weight (m/z 439.2152 [MH+]) corresponding to the acetylated ZmA molecule C15H30N6O9 (34).

Database research.

Transmembrane regions were predicted with the DAS-Transmembrane Prediction server (7) (http://www.sbc.su.se/∼miklos/DAS/).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the ZmA resistance genes of B. thuringiensis strain YBT-1520, zmaWXY, has been assigned GenBank accession number HQ846969.

RESULTS

Construction of a ZmA biosynthesis-related gene cluster linkage group.

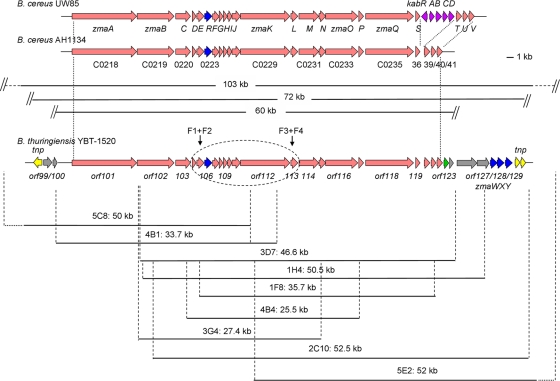

To isolate the ZmA biosynthetic genes, we probed the BAC library constructed from the genomic DNA of B. thuringiensis strain YBT-1520. Based on the sequences of the 5′ and 3′ termini of zma16Bc, the 16-kb region from B. cereus UW85 related to ZmA biosynthesis (8), two primer pairs were designed as the probes (Table 2). The relative positions of the targets amplified by PCR are shown in Fig. 1. Using these two primer pairs, PCR amplification from the YBT-1520 BAC library showed that there were nine BAC clones overlapping zwa16Bc. Both ends of the target BAC clones were sequenced. Comparing the end sequences with the genome sequence of strain YBT-1520 and the restriction maps of the BAC clones (data not shown), the nine BAC clones were all located to the region containing the ZmA biosynthesis-related gene cluster, as indicated in Fig. 1. The isolated BAC clones encompassed ∼103 kb (from the 5′ terminus of clone 5C8 to the 3′ terminus of clone 5E2) of the YBT-1520 genome.

Fig. 1.

Construction of ZmA biosynthesis-related gene cluster BAC clone linkage group and comparison of ZmA gene clusters from three strains. The ZmA biosynthesis genes from B. cereus UW85 and AH1134 that were discovered by Thomas' group are shown at the top (quoted as described in reference 18). The region of zma16Bc is indicated by an ellipse frame on the ZmA gene cluster of strain YBT-1520. The fragments cloned from strain YBT-1520 in nine BAC clones are indicated by black lines under the gene cluster. The names of the clones and the sizes of the DNA fragments are described above the line. Red arrows indicate genes potentially involved in ZmA biosynthesis, blue arrows indicate genes potentially involved in ZmA self-resistance, the green arrow indicates a gene potentially involved in regulation, yellow arrows indicate transposase genes (tnp), gray arrows indicate ORFs without clear functions, and purple arrows denote genes involved in kanosamine biosynthesis in UW85 (kabRABCD). The target position of the two primer pairs F1/F2 and F3/F4 are indicated by two black arrows.

DNA sequencing reveals the potentially intact ZmA biosynthetic gene cluster.

An intact antibiotic gene cluster always comprises three parts: biosynthesis, resistance, and regulation. Sequence analysis of this 103-kb DNA region indicated a 72-kb region which harbors zma16Bc and has putative transposase genes on both ends (Fig. 1, yellow arrows). At the 5′ terminus, there is a putative transposase gene (1,449 bp) showing 99% identity with a transposase gene from a B. thuringiensis strain (accession no. AY566174). At the 3′ terminus, there are two putative transposase genes (encoding proteins of 138 and 290 amino acids [aa]), both showing 96% identity to transposases from B. cereus E33L (accession no. YP_245810 and YP_245811, respectively). The organization and location of these transposase genes suggest that this 72-kb region is a mobile element, and we predicted that this 72-kb mobile element should encompass the intact ZmA gene cluster.

In this 72-kb region, there are 31 ORFs (Fig. 1, orf99 to orf129). Twenty-two of them (orf101 to 122) show high similarities (approximately 98% identity) with the predicted ZmA biosynthetic genes (zmaA to -V) reported by Thomas' group (18) (Fig. 1, red arrows). Adjacent to orf122 (equivalent to zmaV), there are two ORFs: orf123 (774 bp) and orf124 (213 bp). They both show 97% identity to conserved hypothetical proteins (BCAH1134_C0242 and BCAH1134_C0244, respectively) from B. cereus AH1134. In this ZmA producer strain, B. cereus AH1134 (18), these two genes are also located just downstream of the zmaV (gene BCAH1134_C0241). ORF123 possesses a ParBc superfamily domain (aa 12 to 90) and a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif (27). Given that this gene is connected to the predicted ZmA biosynthetic genes, it is probable that ORF123 is involved in the regulation of ZmA biosynthesis (Fig. 1, green arrow).

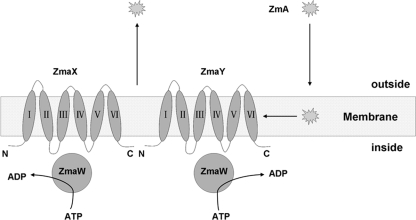

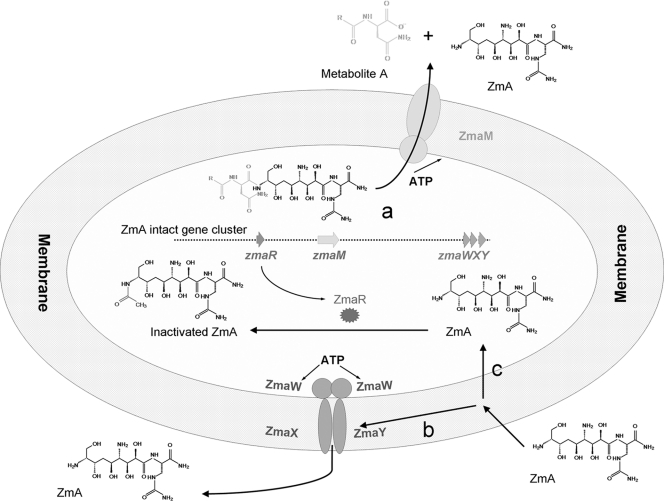

There are three ORFs (orf127 to -129) at the 3′ terminus of this region (Fig. 1, blue arrows). orf127 encodes a 302-aa protein possessing an ATP-binding domain (aa 40 to 190) usually appearing in ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. The next ORFs, orf128 and orf129, whose start codons are GTG, encode 241-aa and 232-aa proteins, respectively. These two ORFs show less than 30% identities to known proteins (data not shown). Both have highly conserved transmembrane domains (TMDs), comprising six trans-membrane α-helices (33). A complete transport complex usually consists of four domains: two ATP-binding domains and two hydrophobic TMDs (15). Based on the above-described similarity, the organization of these three proteins could compose a transport complex. This kind of transport complex has been proven to be involved in resistance to many lantibiotics and is proposed to mediate resistance by active extrusion of lantibiotic molecules from the cytoplasmic membrane (26, 28, 33). Accordingly, we predicted that orf127, orf128, and orf129 are involved in ZmA self-resistance in strain YBT-1520. Their contribution to ZmA resistance is the expulsion of ZmA molecules, most likely from the cytoplasmic membrane into the extracellular medium (Fig. 2). We named orf127, orf128, and orf129 as zmaW, zmaX, and zmaY, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Prediction of the function of zmaWXY in B. thuringiensis strain YBT-1520. A schematic representation of the ABC transporter resistance mechanism encompassing two membrane proteins, ZmaX (ORF128) and ZmaY (ORF129) (each with six TMDs), two ZmaW (ORF127) hydrophilic nucleotide-binding proteins, and the proposed location and function of ZmaWXY. TMDs are predicted by the DAS-Transmembrane Prediction server (33). The six trans-membrane α-helices are indicated by Roman numerals. The ZmA molecule is indicated by a blast dot.

From the above analysis, this 72-kb region would consist of a 60-kb biosynthetic cluster, one regulation gene, and a resistance cluster, as well as the transposase genes at both ends.

Validation of the ZmA biosynthetic gene cluster by heterologous expression.

To confirm the involvement of the isolated DNA fragments in ZmA biosynthesis, we transferred them into a surrogate host, B. thuringiensis strain BMB171, which does not produce ZmA and whose complete genome sequence showed that it lacked the predicted ZmA biosynthesis-related genes (13). Two B. thuringiensis-E. coli shuttle BAC vectors, pEMB0557 and pEMB0603, derived from the typical BAC vector pBeloBAC11 by addition of the plasmid replication origins of B. thuringiensis large plasmids (90-kb and 60-kb native plasmids of strain YBT-1520, respectively), were constructed for the purpose of heterologous expression with large loading capacity. These two shuttle BAC vectors are compatible with each other in Bacillus (unpublished).

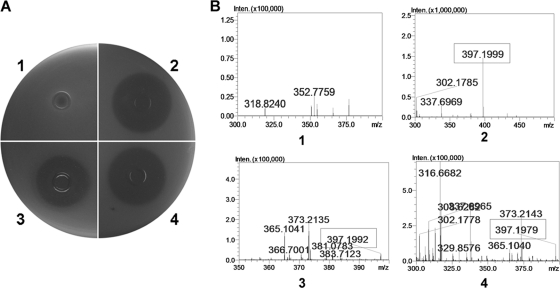

According to the relative positions shown in Fig. 1, we first chose BAC clones 4B1 and 2C10, which together encompass nearly the whole predicted ZmA biosynthetic gene cluster. We transferred their inserts into shuttle BAC vectors pEMB0557 and pEMB0603 at the NotI site, respectively, and then cotransferred them into strain BMB171. The ZmA production of the transformant was checked by detecting inhibition of E. herbicola strain LS005 by the culture filtrate and by using mass spectrometry for the molecular weight of the ZmA molecule. It was found that the DNA inserts of 4B1 and 2C10 could confer ZmA biosynthesis on host strain BMB171 (Fig. 3). To minimize this region, a transformant with the DNA inserts of 4B1 and 3D7 was constructed. This transformant could still produce ZmA, but the growth inhibition zone was slightly smaller than those of 4B1 and 2C10 (Fig. 3). Other transformants constructed to further minimize this region were unable to produce ZmA (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Expression of the ZmA biosynthesis-related gene cluster in a surrogate host, B. thuringiensis strain BMB171. (A) Detection of the ZmA product by agar diffusion tests. A 150-μl volume of culture supernatant was added to each well. (B) LC-MS–IT-TOF detection of a molecular weight corresponding to ZmA in the culture supernatants. The molecular weight corresponding to ZmA is indicated by a rectangular frame. 1, strain BMB171 with vectors pEMB0557 and pEMB0603; 2, strain YBT-1520 (ZmA producer); 3, strain BMB171 with the inserts of BAC clone 4B1 and 3D7; 4, strain BMB171 with the inserts of BAC clone 4B1 and 2C10.

Table 3.

ZmA production by recombinants with various BAC recombinant plasmids

| DNA insert(s) of BAC clones (clone vector) in BMB171 | Inhibition activity of culture filtratea | Mass spectrometry for mol wt of ZmAa |

|---|---|---|

| 4B1 (pEMB0603) + 2C10 (pEMB0557) | + | + |

| 4B1 (pEMB0603) + 3D7 (pEMB0557) | + | + |

| 4B1 (pEMB0603) + 1F8 (pEMB0557) | − | − |

| 4B1 (pEMB0603) + 4B4 (pEMB0557) | − | − |

| 4B1 (pEMB0603) + 3G4 (pEMB0557) | − | − |

| 3D7 (pEMB0557) | − | − |

| 4B1 (pEMB0603) | − | − |

+, inhibition activity was observed or molecular weight of ZmA could be detected; −, inhibition activity was not observed or molecular weight of ZmA could not be detected.

These heterologous expressions demonstrated that the DNA inserts of 4B1 and 3D7 encompass the ZmA biosynthetic gene cluster and that the insert of 3D7 only (or 4B1 and 1F8), which lacks orf101 and orf102 (or orf121 to -124) (Fig. 1), is not sufficient for ZmA biosynthesis. The region comprising 4B1 and 3D7 is approximately 60 kb and contains 24 ORFs (Fig. 1), including all 22 ORFs predicted by Thomas' group to be involved in ZmA biosynthesis. The absence of the zmaWXY genes in the transformant with inserts of 4B1 and 3D7, which can still produce ZmA, suggests that the zmaWXY genes are not essential for ZmA biosynthesis.

The function of the orf123 (which is included in this 60-kb region) was confirmed by a knockout experiment. ZmA production assays for the orf123 mutant BMB1236, carrying an interrupted orf123 gene, demonstrated that this mutant could still produce ZmA, and the area of the growth inhibition zone of 100-μl culture filtrates increased 3.4-fold (the mean of three independent assays) compared to that of strain YBT-1520. Genetic complementation experiments showed that strain BMB1237 which recovered gene orf123 in BMB1236, could generate the same inhibition zone size as strain YBT-1520. These data demonstrated that orf123 is also not essential for ZmA biosynthesis, and the orf123 mutant BMB1236 could yield more ZmA than the wild strain YBT-1520.

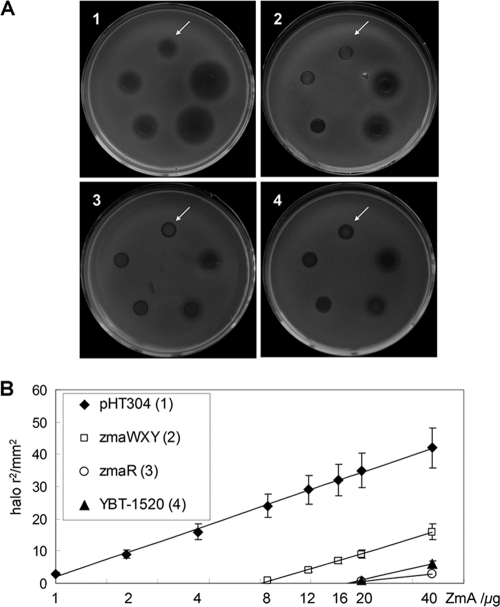

zmaWXY confer resistance against ZmA to B. thuringiensis strain BMB171.

To determine whether the products of zmaWXY act as a ZmA resistance transporter and contribute to ZmA production, we assayed its function in strain BMB171, which is highly sensitive to ZmA (13). zmaWXY and the known ZmA resistance gene zmaR were introduced separately into strain BMB171 using the routine shuttle vector pHT304, resulting in recombinant BMB1231 (ZmaWXY+) and BMB1212 (ZmaR+). Agar diffusion tests showed that zmaWXY conferred improved resistance against ZmA on strain BMB171 compared to strain BMB171 with vector pHT304 only. However, BMB1231 (ZmaWXY+) had less resistance than BMB1212 with zmaR and less than strain YBT-1520, which has both zmaWXY and zmaR (Fig. 4). These data show that ZmA resistance can be conferred on the ZmA-sensitive strain BMB171 by zmaWXY. The data also demonstrated that the acetyltransferase ZmaR and the resistance transporter ZmaWXY could act independently and that ZmaWXY show less tolerance to ZmA than ZmaR. The highest tolerable quantity of ZmA can be calculated from the point of interception with the abscissa, as shown in Fig. 4B. For BMB1212 (ZmaR+), the highest tolerable concentration of ZmA was approximately 200 μg/ml, while for BMB1231 (ZmaWXY+), the value was approximately 80 μg/ml (the point of interception with the abscissa represents approximately 20 and 8 μg ZmA, respectively, and the constant volume of each ZmA sample was 0.1 ml).

Fig. 4.

Functional analysis of ZmA resistance in strain BMB171. The ZmA sensitivities of different strains were detected by agar diffusion tests. (A) Strain BMB171 was transformed with vector pHT304 (plate 1), zmaWXY (plate 2), and zmaR (plate 3); plate 4 contained B. thuringiensis strain YBT-1520. The quantities of ZmA applied to the plates (counterclockwise starting from the arrow) were 1, 2, 4, 20, and 40 μg. ZmA amounts of 8, 12, and 16 μg were also applied in this study but are not shown in these plates. (B) Quantitative representation of the diffusion resistance assay. According to the second law of diffusion (also referred to as Fick's law), the square of the diffusion distance of a given solute in a liquid is directly proportional to the natural logarithm of its initial concentration (33). Thus, with constant volumes (100 μl), linear dependencies between the square of the halos and the natural logarithm of the applied ZmA amounts were obtained. Standard errors were less than 15% for all values (means from three independent assays).

We demonstrated that a transformant with the DNA inserts of 4B1 and 2C10 yields more ZmA than one harboring 4B1 and 3D7, which do not cover zmaWXY (Fig. 3). To further investigate the effect of zmaWXY on ZmA production, growth profiles were carried out for the two recombinants and ZmA quantification was performed from 48-h cultures, conditions under which ZmA yields were maximal. For the transformant with inserts of 4B1 and 3D7, the area of the growth inhibition zone of 150-μl culture supernatants was approximately 420 mm2 (see Fig. S1A2 in the supplemental material), whereas the inhibition area increased 1.3-fold to approximately 550 mm2 for BMB171 with the inserts of 4B1 and 2C10, which included zmaWXY (see Fig. S1A4 in the supplemental material). These data suggested that the transformant with zmaWXY yielded more ZmA than the transformant without zmaWXY.

Furthermore, zmaWXY and zmaR were transferred into B. cereus strain UW85, using pHT304, to detect their contributions to ZmA production in a ZmA native producer strain. For strain UW85 with the vector only, the area of the growth inhibition zone of 100-μl culture supernatants was approximately 320 mm2 (see Fig. S1B3 in the supplemental material). It increased 1.5-fold to approximately 470 mm2 after coexpression of zmaWXY (see Fig. S1B2 in the supplemental material) and increased 2.1-fold to approximately 690 mm2 after coexpression of zmaR (see Fig. S1B4 in the supplemental material). These data showed that the ZmA yield could be enhanced by additional copies of zmaWXY as well as zmaR, which act as the ZmA resistance system.

ZmaWXY expel ZmA from B. thuringiensis strain BMB171.

To clarify the mechanism of action of the ZmA resistance transporter ZmaWXY, a number of recombinants were constructed. zmaWXY were transferred into strain BMB171 via shuttle vector pHT304, resulting in BMB1231 (ZmaWXY+). zmaR was transferred into strain BMB171 via shuttle BAC vector pEMB0603, resulting in BMB1232 (ZmaR+). zmaWXY and zmaR were simultaneously transferred into strain BMB171 via compatible vectors pHT304 and pEMB0603, respectively, resulting in BMB1233 (ZmaR+ and ZmaWXY+). BMB1231 (ZmaWXY+), BMB1232 (ZmaR+), and BMB1233 (ZmaR+ and ZmaWXY+) were incubated in LB medium with 30 μg/ml or 150 μg/ml ZmA overnight. The intracellular contents of all strains were then analyzed by LC-MS–IT-TOF. BMB1231 (ZmaWXY+) could not grow in LB medium with 150 μg/ml ZmA. The molecular weight corresponding to acetylated ZmA, which is the inactive form of ZmA catalyzed by ZmaR, could not be detected in the intracellular fraction of BMB1233 (ZmaR+ and ZmaWXY+) but could be detected in BMB1232 (ZmaR+) with 30 μg/ml ZmA added to the LB medium. The molecular weight corresponding to ZmA also could not be detected in the intracellular fraction of BMB1231 (ZmaWXY+) with 30 μg/ml ZmA added to the LB medium (see Fig. S2A and Table S1 in the supplemental material). These data indicate that ZmA at this concentration (30 μg/ml) cannot migrate into BMB1231 and BMB1233, which harbored zmaWXY or both zmaWXY and zmaR, but can migrate into BMB1232, which harbored only zmaR. When the final concentration of ZmA in medium was increased to 150 μg/ml, the molecular weight corresponding to acetylated ZmA could be detected in the intracellular fraction of BMB1233 (ZmaR+ and ZmaWXY+) (see Fig. S2B and Table S1 in the supplemental material). These results suggest that ZmaWXY can prevent ZmA from diffusing into the cells at lower concentrations, such as 30 μg/ml, but when the final concentration of ZmA in the medium increases to 150 μg/ml or exceeds a concentration limit, ZmA can diffuse into the cells and be inactivated (acetylation) by ZmaR.

Meanwhile, the intracellular contents of a B. thuringiensis strain YBT-1520 (ZmaR+ and ZmaWXY+) culture, whose yield of ZmA is approximately 20 μg/ml, was also subjected to LC-MS–IT-TOF detection. No molecular weight corresponding to acetylated ZmA was found (data not shown). This result confirms that ZmaWXY can prevent ZmA molecules from diffusing into the cells when the concentration of ZmA surrounding the cells corresponds to the level of ZmA production.

DISCUSSION

Secondary metabolites, such as antibiotics, are generally encoded by large and complicated gene clusters, which are difficult to identify. In this study, we developed a straightforward strategy to address this problem. We set out to circumvent the bias when identifying a whole gene cluster by exhaustive bioinformatics analysis of the DNA sequence and by mutation or deletion analysis for the predicted ORFs. The strategy identified a large functional gene cluster from Bacillus by heterologous expression using a series of combinatorial DNA fragments related to the gene cluster in a surrogate host. Compatible shuttle BAC vectors (pEMB0557 and pEMB0603) make it possible to clone large DNA fragments without the capacity limit of the insert size in the BAC library and reduce the pressure of transformation of large recombinant plasmids into Bacillus. By screening the target function of the transformants, a series of combinations of different BAC clone inserts expressed in the surrogate host directly indicate which DNA inserts are obligatory or sufficient for the target function and which are not.

In this study, we present the intact ZmA gene cluster, which is proposed to comprise three parts: biosynthesis, resistance, and regulation. In addition, we validated this gene cluster by heterologous expression. A 60-kb fragment, containing 24 ORFs, was demonstrated to be sufficient for ZmA biosynthesis in a surrogate host, which gives experimental support to the hypothetical ZmA biosynthetic pathway proposed by Thomas' group. No BAC clone that harbored the region covering the 22 ORFs but without orf123 and orf124 (Fig. 1), both of which were not discovered by Thomas' group, was isolated in this work. Therefore, we could not define whether orf123 and orf124 are essential for ZmA biosynthesis by heterologous expression directly. However, further gene knockout experiments showed that the gene orf123 is not essential for ZmA biosynthesis, and the orf123 mutant BMB1236 could yield more ZmA than the wild strain YBT-1520. Given that ORF123 is predicted to be involved in the regulation of ZmA biosynthesis, it is implied that ORF123 may act as a negative regulator of ZmA biosynthesis.

In this study, transposase genes were found at both ends of the 72-kb DNA region which encompasses the intact ZmA gene cluster. Some investigators have insisted that B. thuringiensis acquired insecticidal factors in the course of coevolution with insects through a host-parasite relationship (22, 30). Therefore, it could be predicted that the ZmA gene cluster was acquired in the B. cereus group by horizontal gene transfer. Furthermore, the presence of a sequence with similarities to a B. cereus transposon suggests the possibility that gene transfer between B. cereus and B. thuringiensis occurred. The overall GC content of this 72-kb mobile element, 32.5%, is slightly lower than that of the genomes of many B. thuringiensis and B. cereus strains, such as B. thuringiensis serovar konkukian strain 97-27, B. thuringiensis strain Al Hakam, B. cereus ATCC 14579, B. cereus E33L, and B. thuringiensis strain BMB171, at 35% (5, 10, 13, 16).

Handelsman's group found that the zmaR mutant UW85ΔzmaR was sensitive to high levels of ZmA (300 μg) but could still produce ZmA at near-wild-type levels (12.5 μg/ml of culture) without compromising growth compared to the parent strain, suggesting that zmaR is not essential to ZmA biosynthesis and that another mechanism of self-resistance must be present (8, 35). This additional mechanism of self-resistance has remained undiscovered until now. In this study, three genes, zmaW, zmaX, and zmaY (zmaWXY), were found at the end of the intact ZmA gene cluster and were shown to function as another mechanism of self-resistance against ZmA. Furthermore, zmaWXY, as well as zmaR, were found to contribute to the increased yield of ZmA, which agrees with reports that the introduction of additional antibiotic resistance genes into antibiotic-producing bacteria results in increased antibiotic production (6, 14). It is probable that the presence of additional copies of zmaWXY and zmaR in a ZmA producer strain could reduce the growth pressure of ZmA on the mother cells and stimulate the yield of ZmA.

Taken together, the whole mechanism for ZmA self-resistance of the producer strain can be predicted. First, the metabolite (acyl-d-Asn-ZmA) synthesized by the gene cluster is cleaved by the secretion transporter ZmaM between d-Asn and d-Ser, releasing ZmA and fatty acyl-d-Asn (metabolite A). The secretion transporter ZmaM then exports them out of the cell (18) (Fig. 5a). ZmA in the culture supernatants could easily interact with the cytoplasmic membrane. The resistance transporter ZmaWXY will recognize it and expel it from the cytoplasmic membrane, thus keeping ZmA molecules out of the cell (Fig. 5b). This process requires ATP to provide energy. If the concentration of ZmA in the culture supernatants is higher than the concentration that ZmaWXY can cope with, ZmA molecules could diffuse into the cell. Once the ZmA molecules get into the cell, ZmaR acetylates ZmA, thereby inactivating it and rendering the cell resistant to ZmA (Fig. 5c). This hypothesis provides a reasonable explanation for why the B. cereus mutant UW85ΔzmaR is sensitive to ZmA at a high concentration (300 μg per well) but at a low concentration of ZmA can still produce near-wild-type levels of ZmA (12.5 μg/ml of culture) (8).

Fig. 5.

Schematic model for the transport and resistance of ZmA. ZmA is synthesized by the gene cluster indicated by a dotted line. Resistance genes zmaR and zmaWXY, and secretion transporter gene zmaM are shown on the dotted line. ZmaM and ZmaWXY are located on the membrane, while ZmaR is located in the intracellular space. Black arrows indicate the pathway of ZmA secretion and self-resistance in the ZmA producer strain. See the text for a detailed description of the proposed model.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program (863 Program) of China (grants 2011AA10A203, 2006AA02Z174, and 2006AA10A212), National Basic Research Program (973 Program) of China (grant 2009CB118902), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 30770020 and 30970037), Genetically Modified Organisms Breeding Major Projects of China (grant 2009ZX08009-032B), and 948 Program of China (grant 2006-4-41).

We are grateful to Jo Handelsman (University of Wisconsin—Madison) for providing the ZmA-producing strain B. cereus UW85.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 5 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arantes O., Lereclus D. 1991. Construction of cloning vectors for Bacillus thuringiensis. Gene 108:115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blodgett J. A., Zhang J. K., Metcalf W. W. 2005. Molecular cloning, sequence analysis, and heterologous expression of the phosphinothricin tripeptide biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces viridochromogenes DSM 40736. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:230–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Broderick N. A., Goodman R. M., Raffa K. F., Handelsman J. 2000. Synergy between zwittermicin A and Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. Kurstaki against gypsy moth (Lepidoptera:Lymantriidae). Environ. Entomol. 29:101–107 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bumpus S. B., Evans B. S., Thomas P. M., Ntai I., Kelleher N. L. 2009. A proteomics approach to discovering natural products and their biosynthetic pathways. Nat. Biotechnol. 27:951–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Challacombe J. F., et al. 2007. The complete genome sequence of Bacillus thuringiensis Al Hakam. J. Bacteriol. 189:3680–3681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crameri R., Davies J. E. 1986. Increased production of aminoglycosides associated with amplified antibiotic resistance genes. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 39:128–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cserzö M., Wallin E., Simon I., von Heijne G., Elofsson A. 1997. Prediction of transmembrane alpha-helices in prokaryotic membrane proteins: the dense alignment surface method. Protein Eng. 10:673–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Emmert E. A., Klimowicz A. K., Thomas M. G., Handelsman J. 2004. Genetics of zwittermicin A production by Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:104–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gullón S., et al. 2006. Isolation, characterization, and heterologous expression of the biosynthesis gene cluster for the antitumor anthracycline steffimycin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4172–4183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Han C. S., et al. 2006. Pathogenomic sequence analysis of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis isolates closely related to Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 188:3382–3390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Handelsman J., Raffel S., Mester E. H., Wunderlich L., Grau C. R. 1990. Biological control of damping-off of alfalfa seedlings with Bacillus cereus UW85. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:713–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He H. Y., Silo-Suh L. A., Handelsman J., Clardy J. 1994. Zwittermicin A, an antifungal and plant protection agent from Bacillus cereus. Tetrahedron Lett. 35:2499–2502 [Google Scholar]

- 13. He J., et al. 2010. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus thuringiensis mutant strain BMB171. J. Bacteriol. 192:4074–4075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heinzmann S., Entian K. D., Stein T. 2006. Engineering Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 for improved production of the lantibiotic subtilin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 69:532–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Higgins C. F. 1992. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 8:67–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ivanova N., et al. 2003. Genome sequence of Bacillus cereus and comparative analysis with Bacillus anthracis. Nature 423:87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kawasaki T., et al. 2006. Biosynthesis of a natural polyketide-isoprenoid hybrid compound, furaquinocin A: identification and heterologous expression of the gene cluster. J. Bacteriol. 188:1236–1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kevany B. M., Rasko D. A., Thomas M. G. 2009. Characterization of the complete zwittermicin A biosynthesis gene cluster from Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:1144–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu X. Y., et al. 2009. Construction of an Escherichia coli to Bacillus thuringiensis shuttle vector for large DNA fragments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 82:765–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu X. Y., et al. 2010. Genome wide screening revealed the genetic determinants of an antibiotic insecticide in Bacillus thuringiensis. J. Biol. Chem. 285:39191–39200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luo M. Z., Wing R. A. 2003. An improved method for plant BAC library construction, p. 3–19 In Grotewold E. (ed.), Plant functional genomics: methods and protocols. Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mahillon J., Chandler M. 1998. Insertion sequences. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:725–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Milner J. L., Stohl E. A., Handelsman J. 1996. Zwittermicin A resistance gene from Bacillus cereus. J. Bacteriol. 178:4266–4272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ohse M., Takahashi K., Kadowaki Y., Kusaoke H. 1995. Effects of plasmid DNA sizes and several other factors on transformation of Bacillus subtilis ISW1214 with plasmid DNA by electroporation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 59:1433–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peng D. H., et al. 2009. Elaboration of an electroporation protocol for larger plasmids and wild-type strains in Bacillus thuringiensis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106:1849–1858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peschel A., Götz F. 1996. Analysis of the Staphylococcus epidermidis genes epiF, -E, and -G involved in epidermin immunity. J. Bacteriol. 178:531–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Quisel J. D., Grossman A. D. 2000. Control of sporulation gene expression in Bacillus subtilis by the chromosome partitioning proteins Soj (ParA) and Spo0J (ParB) J. Bacteriol. 182:3446–3451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rincé A., Dufour A., Uguen P., Le Pennec J. P., Haras D. 1997. Characterization of the lacticin 481 operon: the Lactococcus lactis genes lctF, lctE, and lctG encode a putative ABC transporter involved in bacteriocin immunity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4252–4260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schnepf E., et al. 1998. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:775–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Silo-Suh L. A., et al. 1994. Biological activities of two fungistatic antibiotics produced by Bacillus cereus UW85. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:2023–2030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Silo-Suh L. A., Stabb E. V., Raffel S. J., Handelsman J. 1998. Target range of zwittermicin A, an aminopolyol antibiotic from Bacillus cereus. Curr. Microbiol. 37:6–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stein T., Heinzmann S., Düsterhus S., Borchert S., Entian K. D. 2005. Expression and functional analysis of the subtilin immunity genes spaIFEG in the subtilin-sensitive host Bacillus subtilis MO1099. J. Bacteriol. 187:822–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stohl E. A., Brady S. F., Clardy J., Handelsman J. 1999. ZmaR, a novel and widespread antibiotic resistance determinant that acetylates zwittermicin A. J. Bacteriol. 181:5455–5460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stohl E. A., Milner J. L., Handelsman J. 1999. Zwittermicin A biosynthetic cluster. Gene 237:403–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Turgeon N., Laflamme C., Ho J., Duchaine C. 2006. Elaboration of an electroporation protocol for Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579. J. Microbiol. Methods 67:543–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wenzel S. C., Müller R. 2005. Recent developments towards the heterologous expression of complex bacterial natural product biosynthetic pathways. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 16:594–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhao C. M., et al. 2007. Identification of three zwittermicin A biosynthesis-related genes from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki strain YBT-1520. Arch. Microbiol. 187:313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhao C. M., Song C. X., Luo Y., Yu Z. N., Sun M. 2008. l-2,3-Diaminopropionate: one of the building blocks for the biosynthesis of zwittermicin A in Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki strain YBT-1520. FEBS Lett. 582:3125–3131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.