Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Gag protein targets to the plasma membrane and assembles into viral particles. In the next round of infection, the mature Gag capsids disassemble during viral entry. Thus, Gag plays a central role in the HIV life cycle. Using a yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid assay based on the SOS-RAS signaling system, we developed a system to measure the Gag-Gag interaction and isolated 6 candidates for Gag assembly inhibitors from a chemical library composed of 20,000 small molecules. When tested in the human MT-4 cell line and primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells, one of the candidates, 2-(benzothiazol-2-ylmethylthio)-4-methylpyrimidine (BMMP), displayed an inhibitory effect on HIV replication, although a considerably high dose was required. Unexpectedly, neither particle production nor maturation was inhibited by BMMP. Confocal microscopy confirmed that BMMP did not block Gag plasma membrane targeting. Single-round infection assays with envelope-pseudotyped and luciferase-expressing viruses revealed that BMMP inhibited HIV replication postentry but not simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) or murine leukemia virus infection. Studies with HIV/SIV Gag chimeras indicated that the Gag capsid (CA) domain was responsible for the BMMP-mediated HIV postentry block. In vitro studies indicated that BMMP accelerated disassembly of HIV cores and, conversely, inhibited assembly of purified CA protein in a dose-dependent manner. Collectively, our data suggest that BMMP primarily targets the HIV CA domain and disrupts viral infection postentry, possibly through inducing premature disassembly of HIV cores. We suggest that BMMP is a potential lead compound to develop antiretroviral drugs bearing novel mechanisms of action.

INTRODUCTION

Over 2 decades, research has developed antiretroviral therapy (ART) with a combination of antiretroviral drugs for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection (10). ART has dramatically improved the survival of HIV-1-infected individuals. Current ART involves a combination of inhibitors of HIV-specific enzymes, such as protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase (IN). In some cases, inhibitors of HIV-1 entry are also used. However, the emergence of HIV-1 variants resistant to antiretroviral drugs during ART stresses the need for novel HIV-1 inhibitors against distinct targets.

Multiple screening approaches have been employed for HIV-1 drug discovery (37) and have successfully discovered HIV-1 inhibitors that are currently available: nucleoside analogue RT inhibitors were discovered by HIV replication assays (23) and PR inhibitors were produced by structure-based drug design (25). In general, cell-free assays allow discovery of compounds with a relatively low 50% effective dose (ED50) in vitro. However, many such compounds often fail to inhibit HIV-1 replication in in vivo assays, because they may not penetrate the cell membrane or may easily be catalyzed in metabolic environments. Also, possible toxic effects of the compounds must be tested in a subsequent cell culture study. In contrast, cell-based screens can exclude toxic compounds but have the disadvantages of time requirements and limitations on cell propagation in high-throughput screening.

Recently, cell-based assays using engineered cells and microorganisms have become an attractive alternative to in vitro assays for high-throughput screening. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a convenient alternative to mammalian cells for this purpose. Comparative genomic analysis has shown that approximately 30% of yeast genes have homology to the mammalian protein sequences (8), indicating that basic cellular mechanisms are well conserved between yeast and human cells. Yeast has been used as a model organism for understanding biological functions of higher eukaryotic cells, leading to accumulation of scientific knowledge in yeast genetics and molecular biology. Such pioneering research has allowed the development of molecular technologies (e.g., two-hybrid assay and galactose induction), genetically modified cells (e.g., temperature sensitivity and conditional lethality), and cell selection systems (e.g., URA3 nutritional selection), enabling the construction of simple readout assay systems.

Gag protein, the main structural component of retrovirus, directs particle assembly. HIV Gag protein is synthesized as a precursor protein, p55, which is composed of matrix (MA), capsid (CA), nucleocapsid (NC), and p6 domains, and cotranslationally myristoylated at the N-terminal glycine. Concomitant with the N-terminal myristoylation, p55Gag is targeted to the plasma membrane and assembled into virus particles (13, 22). During particle release, Gag undergoes proteolytic processing to generate the CA domain that forms the mature capsid. In the next round of infection, the mature capsid disassembles during viral penetration into host cell cytoplasm. Thus, the capsid assembly and disassembly are reverse reactions during virus release and entry and must be regulated by yet-unknown mechanisms. Indeed, the optimal stability of HIV-1 capsid is required for efficient infection (14). We have previously shown that the particle assembly process is reproducible in a yeast cell system (26). Here, we further developed a yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid assay system in which a temperature-sensitive mutant strain of yeast grows at restrictive temperature when Gag-Gag interactions occur. Using this yeast two-hybrid system, we have screened a chemical library composed of 20,000 low-molecular-weight compounds and have found a compound that targets CA-CA interactions and inhibits HIV-1 replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction and transformation of yeast expression plasmids.

A yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid assay based on the CytoTrap SOS recruitment system (Stratagene) was employed in this study. The full-length gag gene of HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) was placed downstream of the yeast inducible promoter for the GAL1 gene in frame with the cDNA of SOS in a pSOS plasmid (Stratagene) that contains the LEU2 gene as a yeast selective marker. The HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) gag gene was also cloned into pMyr plasmid, which contains a yeast inducible promoter for the GAL1 gene and the URA3 gene as a selective marker. The S. cerevisiae strain cdc25Ha (MATa ura3-52 his3-200 ade2-101 lys2-801 trp1-901 leu2-3 112 cdc25-2 Gal+) was doubly transformed with the yeast expression plasmids.

Chemical library screening in CytoTrap yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid system.

Yeast transformants were initially grown at 25°C in synthetic defined medium with glucose (0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% glucose, and amino acid mixtures without uracil or leucine) (permissive conditions). After being washed, culture was diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 in synthetic defined medium with galactose and raffinose (0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% galactose, 2% raffinose, and amino acid mixtures without uracil or leucine) for Gag expression. The yeast culture (OD600 = 0.1) was incubated with a chemical library (a final concentration of 10 μM) at 37°C for 5 days (restrictive conditions) in 96-well microtiter plates with shaking. The chemical library (preplated Diversity Set) was purchased from Enamine. After complete resuspension of cells by vortexing of microtiter plates, cell density was measured at 600 nm by a plate reader (Infinite200; Tecan).

Mammalian cells and transfection.

293T, HeLa, and MT-4 cells were provided by the AIDS Research Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan. 293FT cells were purchased from Invitrogen. Peripheral blood monocytic cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Conray density centrifugation from healthy donors. All mammalian cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Japan Bioserum, Japan), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen), at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. For PBMC culture, GlutaMax-I (Invitrogen), insulin-transferrin-selenium A (Invitrogen), 200 ng/ml anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (OKT3; Janssen Pharmaceutical), and 70 U/ml recombinant human interleukin-2 (IL-2; Shionogi Pharmaceutical, Japan) were further added to the medium. Transfection was carried out with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen).

Cell toxicity assays.

For determining the toxicity of the chemical library to yeast, yeast cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.01 and incubated under permissive conditions (at 25°C in glucose medium) with the chemical library. After 2 days, cell density was measured at 600 nm by a plate reader (Infinite200; Tecan). For determining toxicity to mammalian cells, 293T, 293FT, HeLa, and MT-4 cells and PBMC were incubated with compounds at 37°C for 2 to 14 days and subjected to 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) and Alamar Blue assays according to the manufacturer's instructions. The OD of the MTS assay mixture was measured at 490 nm, and the OD of the Alamar Blue assay mixture was measured at 570 nm by a plate reader (FLx800; BioTek). The 50% cytotoxicity concentrations were defined as drug concentrations by which the OD values reached the 50% level of the no-drug (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) controls.

HIV-1 replication assays.

MT-4 Luc cells that were transduced with luciferase in MT-4 cells (31) and PBMC were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. MT-4 Luc cells were infected with HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) corresponding to 1.25 ng of p24CA antigen and incubated at 37°C in the presence of compounds. On day 7, MT-4 Luc cells were subjected to luciferase assay. PBMC were stimulated with IL-2 and anti-CD3 antibody. Following infection with HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) corresponding to approximately 5 ng of p24CA antigen, PBMC were incubated at 37°C and passaged every 3 to 4 days in the presence of compounds. The culture supernatants of PBMC were temporally collected and subjected to quantification of HIV-1 particle yields by p24CA antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Zeptometrix).

Single-round infection assays.

For single-round infection assays, HIV-1 was pseudotyped with either HIV-1 Env protein or vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) G protein as described previously (35). Briefly, 293FT cells were transfected with a plasmid containing the codon-optimized HXB2 gag-pol gene (pHIVgag-pol), a lentiviral plasmid expressing luciferase (pLenti-luciferase), a plasmid expressing HIV-1 Rev (pRevpac), and either a plasmid expressing HIV-1 Env or a plasmid expressing VSV-G. Culture media were harvested and inoculated into MT-4 and 293FT cells in the presence of 5 to 10 μg/ml dextran (ICN). HIV-1 pseudotyped with autologous HIV-1 Env protein was inoculated into 293FT-CD4 (expressing CD4 constitutively) cells. On day 2 or 3, infectivity was assessed by luciferase activity transduced by pLenti-luciferase. HIV-1 (NL43 strain) expressing luciferase, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) (mac239 strain), and murine leukemia virus (MLV) (Moloney strain) were similarly pseudotyped with VSV-G (28). The viruses were enriched by centrifugation through sucrose cushions if necessary.

HIV/SIV Gag chimeras were generated in the context of pHIVgag-pol by replacing the MA and CA domains with the SIV MA and CA domains, respectively. The Gag chimeras contain the cleavage site sequences of HIV-1 Gag at the chimera junctions. Amino acid substitutions G89A and P90A in the cyclophilin A (CypA)-binding loop of CA (corresponding to Gag amino acid positions 225 and 226) (11, 16) were carried out by overlap PCR in the context of pHIVgag-pol.

Quantitative PCR for HIV-1 cDNA synthesis.

MT-4 cells were infected with HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) and incubated in the presence of compounds. Efavirenz (EFV) was provided by the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program and was used as positive control. The cellular genomic DNA was extracted 4 and 24 h postinfection with a DNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cellular DNA was subjected to quantitative real-time PCR using the Quantitec probe PCR kit containing SYBR green (Qiagen). The following primer sets were used: 5′-AACTAGGGAACCCACTGCTTAAG-3′ and 5′-CTGCTAGAGATTTTCCACACTGAC-3′ (specific for the R-U5 region in early reverse transcripts of HIV-1 cDNA), 5′-CCGTCTGTTGTGTGACTCTGGT-3′ and 5′-GAGTCCTGCGTCGAGAGAGCT-3′ (specific for the late reverse transcripts of HIV-1 cDNA), 5′-TGCTGGGATTACAGGCGTGAG-3′ and 5′-CTGCTAGAGATTTTCCACACTGAC-3′ (specific for long terminal repeat [LTR] and Alu region in the integrated HIV-1 cDNA), and 5′-AACTAGGGAACCCACTGCTTAAG-3′ and 5′-CTGCTAGAGATTTTCCACACTGAC-3′ (second PCR) (specific for LTR region in the integrated HIV-1 cDNA) (12). The amplification kinetics was monitored by the Opticon 2 system (Bio-Rad). The levels of cellular DNA were normalized by the levels of β-globin DNA quantified using primers 5′-TATTGGTCTCCTTAAACCTGTCTTG-3′ and 5′-CTGACACAACTGTGTTCACTAGC-3′ (19).

Viral protein expression and particle purification.

HIV-1 proviral clone pHXB2 was transfected into 293FT and HeLa cells in the presence of increasing doses of 2-(benzothiazol-2-ylmethylthio)-4-methylpyrimidine (BMMP). After 2 days, cells were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HIV-1 p24CA monoclonal antibody (100-fold diluent of 183-H12-5C hybridoma culture supernatant; NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program). HIV particles were collected by centrifugation through 20% (wt/vol) sucrose cushions in an SW55 rotor (Beckman Coulter) at 120,000 × g for 1 h. For HIV/SIV Gag chimeras, 293FT cells were cotransfected with pHIVgag-pol expressing Gag chimera, pLenti-luciferase, pRevpac, and a plasmid expressing VSV-G. Cells and purified particles were similarly analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HIV-1 p24CA, anti-HIV-1 p17MA (2 μg/ml; 13-103-100; Advanced Biotechologies), and anti-SIV p27CA (1 μg/ml; 4324; Advanced Bioscience Laboratories) monoclonal antibodies.

In vitro assembly reaction of CA.

The in vitro assembly reaction of CA was performed as described previously (17, 36). Briefly, the purified HIV-1 CA (a final concentration of 100 μM) was incubated at 37°C for 1 h in buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. Assembly products were pelleted by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C and were subjected to p24CA antigen capture ELISA (Zeptometrix) and electron microscopy.

In vitro disassembly reaction of capsid cores.

The in vitro disassembly assay was performed according to Aiken's method with some modifications (3). HIV particles were purified by ultracentrifugation through 20% (wt/vol) sucrose cushions. For isolation of HIV capsid cores, purified HIV particles were applied onto sucrose step gradients composed of 7.5% (wt/vol), 15% (wt/vol) containing 1% Triton X-100, and 30 to 70% (wt/vol) sucrose and subjected to centrifugation at 120,000 × g for 16 h at 4°C. Fractions rich in HIV cores were collected and resuspended in buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA). For core disassembly assays, aliquots of HIV cores were incubated at 37°C in the presence of compounds. For comparison, azidothymidine (AZT) (Moravek Biochemicals) was added to the reaction mixture. Intact cores were recovered by centrifugation at 125,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C.

Confocal microscopy and electron microscopy.

HeLa cells were transfected with a pNL43 derivative expressing Gag-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein but not pol gene products. Cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min at room temperature and were treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature for membrane permeabilization. Following nuclear staining with TO-PRO-3 (Molecular Probes), cells were mounted with antibleaching reagent and observed with a laser scanning microscope (TCS; Leica).

In vitro assembly products were adsorbed onto carbon-coated copper grids and stained with 2% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate. Sections were subjected to electron microscopy.

Statistical analysis.

Intergroup comparisons were performed with paired t test (for parametric group analysis). All P values were considered significant if less than 0.05.

RESULTS

A yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid system for HIV-1 Gag-Gag interactions.

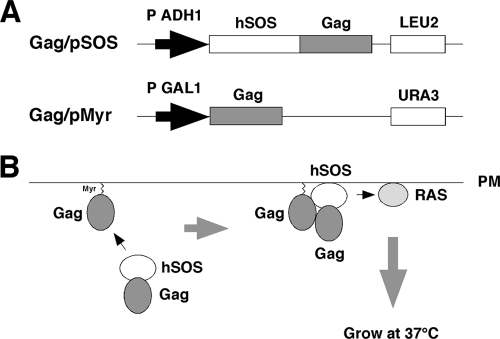

For construction of a yeast cell-based Gag assembly system, we employed a yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid assay based on the CytoTrap SOS recruitment system (Stratagene) in this study (Fig. 1). For HIV-1 Gag expression, two yeast expression plasmids, pMyr and pSOS, were used: pMyr contains the yeast inducible promoter for the GAL1 gene followed by a myristoylation signal (amino acid sequence, MGSSKSKPKDPSQRR) for membrane targeting and pSOS contains the constitutive promoter for the yeast ADH gene followed by the human SOS gene. The gag gene of HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) was cloned in frame with the myristoylation signal in pMyr. The gag gene was similarly cloned in frame with the SOS gene in pSOS that allowed production of SOS-Gag fusion protein (Fig. 1A). The S. cerevisiae cdc25H strain was doubly transformed with these Gag expression plasmids. The cdc25H strain contains a temperature-sensitive mutation in the CDC25 gene, which allows growth at 25°C (permissive temperature) but not at 37°C (restrictive temperature). SOS is the human orthologue of the yeast CDC25 and can activate the yeast RAS signal transduction pathway that complements the yeast cdc25 defect (4). When myristoylated Gag and SOS-Gag are coexpressed in the cdc25H cells, the SOS-Gag is recruited to the plasma membrane through an interaction with the myristoylated Gag, leading to growth of the cdc25H cells at 37°C (Fig. 1B). We initially confirmed that the cdc25H cells transformed with the Gag/pMyr and Gag/pSOS plasmids grew at 37°C in galactose plus raffinose medium under conditions in which SOS-Gag fusion protein was expressed but not at 37°C in glucose medium under conditions in which SOS-Gag fusion was not expressed.

Fig. 1.

Yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid screening for inhibitors of Gag-Gag interaction. (A) Schematic representation of Gag expression plasmids used for yeast SOS recruitment system. The full-length gag gene of HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) was expressed by yeast expression plasmids pMyr and pSOS: pMyr contains the yeast inducible promoter for the GAL1 gene and the URA3 gene as a selective marker and pSOS contains the constitutive promoter for the yeast ADH gene and the LEU2 gene as a selective marker. (B) Principle of yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid assay based on SOS recruitment system. The schematic illustration was adapted with permission from the manuals for the CytoTrap yeast system (Agilent Technologies, Inc.; http://www.genomics.agilent.com/CollectionSubpage.aspx?PageType=Product&SubPageType=ProductDetail&PageID=1311).

Screening of a chemical library for Gag-Gag interaction inhibitors by yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid assays.

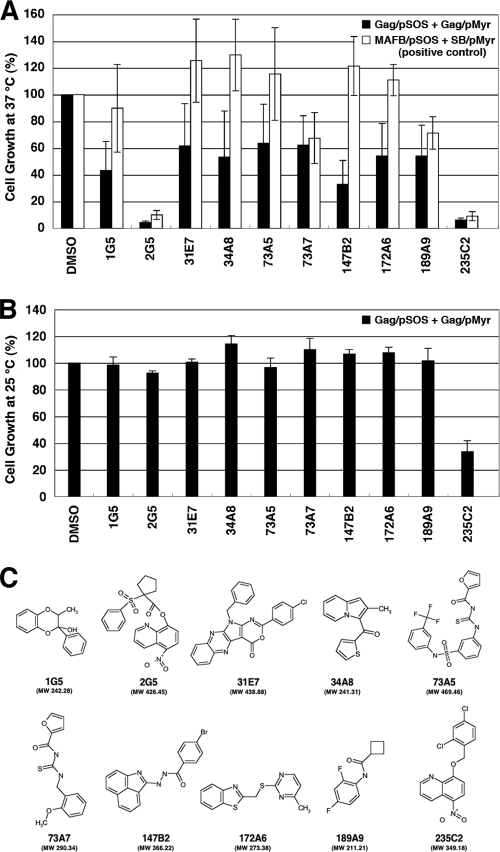

For screening for inhibitors of Gag assembly, we optimized this yeast membrane-associated Gag-Gag interaction system to a liquid format using 96-well microplates. Using this system, we screened a chemical library composed of 20,000 compounds, each of which was initially designated by the numbers of microplates and wells of the chemical library (e.g., 172A6 indicates microplate number 172 and well number A6). When the cdc25H transformant was incubated at 37°C in galactose plus raffinose medium with a chemical library (10 μM each), we found 10 compounds that reduced cell growth (Fig. 2A, black columns). To examine if cell growth reduction is specifically due to the disruption of Gag-Gag interaction, we used another cdc25H transformant that contained MAFB/pSOS and SOS binding protein/pMyr plasmids. This combination produces SOS-MAFB fusion protein and myristoylated SOS binding protein and can be used as a positive control for the CytoTrap system (Stratagene). When using this positive control, we observed that 4 compounds (2G5, 73A7, 189A9, and 235C2) out of the 10 compounds also reduced cell growth (Fig. 2A, white columns), suggesting that they might inhibit pathways which are commonly used in the CytoTrap system (e.g., N myristoylation and RAS signaling). Thus, we concluded that 6 compounds (1G5, 31E7, 34A8, 73A5, 147B2, and 172A6) specifically inhibited a Gag-Gag interaction. No common chemical structures were found among the 6 candidates. However, 3 chemicals (34A8, 147B2, and 172A6) share relatively similar structures whereby two allyl groups are connected by a short linker moiety. To test the cell toxicity, the cdc25H transformants were incubated at 25°C in glucose medium (permissive conditions) with the compounds (10 μM each) (Fig. 2B). All the compounds except 235C2 allowed cell growth at levels comparable to that obtained in the presence of DMSO (as a control). Further studies revealed that 235C2 preferentially inhibited growth of several fungi in vitro (e.g., Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus at MICs of 5.7 and 10 μM, respectively) (data not shown), suggesting that it might serve as a lead compound to develop an antifungal agent. The chemical formulas of 10 compounds are shown in Fig. 2C.

Fig. 2.

Screening for inhibitors of Gag assembly by yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid assays. (A) The yeast cdc25Ha strain was transformed with the pSOS and pMyr plasmids. The yeast culture was diluted to an OD600 of 0.1 and incubated at 37°C in galactose-plus-raffinose medium (restrictive conditions) with a chemical library (a final concentration of 10 μM). After growth at 37°C for 5 days, cell density was measured at OD600. As a control, the OD600 of yeast incubated in the presence of DMSO was set to 100%. The yeast transformed with the pSOS and pMyr plasmids, both of which contained the HIV-1 gag gene, was shown as black columns, and the yeast was transformed with the pSOS plasmid containing MAFB and the pMyr plasmid containing the cDNA of SB (as a positive-control combination) as white columns. Data were shown as means with standard deviations from 5 independent experiments. (B) The yeast cdc25Ha strain transformed with the pSOS and pMyr plasmids containing the HIV-1 gag gene was grown at 25°C in glucose medium. The yeast culture was diluted to an OD600 of 0.01 and incubated at 25°C in glucose medium with a chemical library (a final concentration of 10 μM). After growth at 25°C for 2 days, cell density was measured at OD600. As a control, the OD600 of yeast incubated in the presence of DMSO was set to 100%. Data were shown as means with standard deviations from 3 independent experiments. (C) Structures of compounds screened from a chemical library by yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid assays.

Inhibition of HIV replication in mammalian cells by compounds identified as yeast membrane-associated Gag-Gag interaction inhibitors.

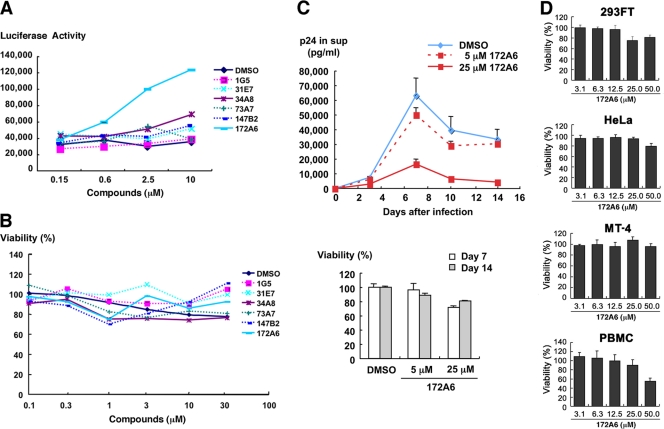

We evaluated the anti-HIV activity of the 6 candidates in mammalian cell systems. MT-4 Luc cells (human T lymphocytic cell line expressing luciferase constitutively) were infected with HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) and incubated at 37°C in the presence of the test compounds. In this T cell system, the luciferase activity is reduced by HIV-1 infection, due to the cell death upon HIV-1 replication (31). When added to HIV-1-infected MT-4 Luc cells, one of the candidates (172A6) recovered the luciferase expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A), indicating that 172A6 was capable of reduction in HIV replication in mammalian cells. When 293T cells were incubated with the 6 compounds and were subjected to Alamar Blue assays, none of the compounds showed apparent reduction in cell viability (Fig. 3B). To confirm the anti-HIV effect, PBMC were infected with HIV-1 in the presence of 172A6 and production of HIV in the culture medium was temporally measured by p24CA antigen capture ELISA. 172A6 limited HIV replication at 5 μM and severely inhibited it at 25 μM (Fig. 3C, upper panel). When uninfected PBMC were similarly exposed to 172A6 and assessed by MTS assays, a slight reduction in cell viability was observed at 25 μM (Fig. 3C, lower panel). However, the severe inhibition of HIV replication at 25 μM 172A6 could not be ascribed fully to its cytotoxic effect. Using several mammalian cell lines, we reevaluated cytotoxicity of 172A6 by MTS assays. No significant cytotoxicity of 172A6 was seen in the cell lines, except in PBMC, that we used in this study (Fig. 3D). Based on the chemical structure [2-(benzothiazol-2-ylmethylthio)-4-methylpyrimidine] of the compound 172A6 (Fig. 2C), we called it BMMP here.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of HIV-1 replication and cell toxicity. (A) MT-4 Luc cells were infected with HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) and incubated at 37°C in the presence of increasing doses of compounds. On day 7, MT-4 Luc cells were subjected to luciferase assay. Data were shown as means from triplicate cultures. (B) 293T cells were incubated with various doses of compounds at 37°C for 2 days and subjected to Alamar Blue assays. Data were shown as means from 3 independent experiments. (C) PBMC stimulated with IL-2 and anti-CD3 antibody were infected with HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) and incubated at 37°C in the presence of 5 and 25 μM 172A6. HIV-1 production in culture medium was temporally quantified by p24CA antigen capture ELISA (top). Uninfected PBMC were cultured with 172A6 at 37°C and were subjected to MTS assay on days 7 and 14. Data were shown as means with standard deviations from triplicate cultures, in which DMSO was used as control. (D) 293FT, HeLa, and MT-4 cells and PBMC were incubated at 37°C with various doses of 172A6 and were subjected to MTS assay on days 4, 3, 4, and 6, respectively. Cell viability was shown as OD490. Data were shown as means with standard deviations from triplicate cultures.

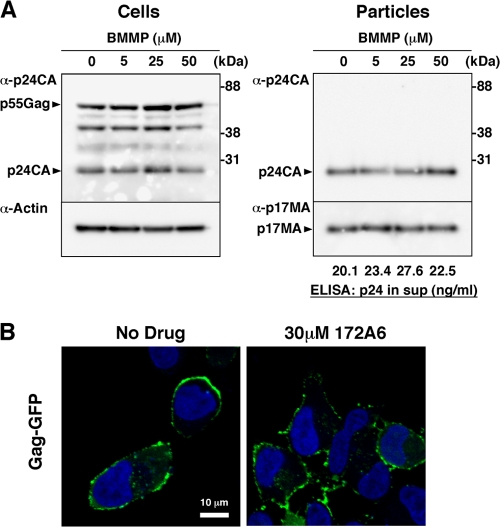

No inhibition of HIV particle release by BMMP.

We initially examined whether BMMP inhibited HIV-1 particle production. 293FT cells were transfected with pHXB2 and incubated at 37°C in the presence of 5 to 50 μM BMMP. Western blotting using anti-HIV-1 p24CA antibody revealed that the intracellular level of Gag expression and the pattern of Gag processing were largely unaffected in the presence of BMMP (Fig. 4A), suggesting that BMMP did not inhibit HIV protease. When purified particle fractions were similarly analyzed, we found no reduction in particle production (Fig. 4A). We obtained similar results on HeLa cells. This indicates that BMMP did not block HIV-1 particle release.

Fig. 4.

HIV-1 particle production and Gag plasma membrane targeting. (A) Effects on HIV-1 particle production. 293FT cells were transfected with pHXB2 and incubated at 37°C with 0 to 50 μM BMMP. Two days posttransfection, cells were collected and culture media were subjected to purification of viral particles by ultracentrifugation. Equivalent volumes of samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using anti-HIV-1 p24CA antibody. Representative blots were shown. HIV-1 particle yields in culture media were quantified by p24CA antigen capture ELISA. (B) Intracellular localization of Gag. HeLa cells were transfected with a pNL43 derivative in which Gag was fused with GFP and incubated at 37°C for 1.5 days with 30 μM BMMP. Nuclei were stained with TO-PRO-3, and cells were observed by confocal microscopy. Representative images were shown at the same magnification. Bar = 10 μm.

Intracellular distribution of Gag was examined by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4B). HeLa cells were transfected with a pNL43 derivative that expresses Gag-GFP and incubated with 30 μM BMMP. Gag-GFP was distributed predominantly at the plasma membrane in cells treated with DMSO (used as control). A similar Gag-GFP distribution was observed in cells treated with BMMP, indicating that BMMP did not inhibit Gag targeting to the plasma membrane, consistent with the above findings.

Inhibition of HIV replication postentry by BMMP.

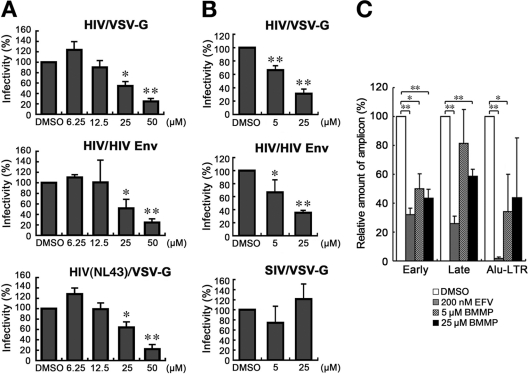

To examine whether BMMP exerted an inhibitory effect on early stages of the HIV life cycle, such as viral entry, we employed single-round infection assays with luciferase-expressing HIV-1 vectors which were pseudotyped with either VSV-G or authentic HIV-1 Env protein. To this end, pHIVgag-pol (for expression of HIV-1 Gag and Gag-Pol), pRevpac (for expression of HIV-1 Rev), and pLenti-luciferase vector, which provides the artificial lentiviral genome expressing luciferase driven by cytomegalovirus promoter, were cotransfected with either VSV-G or authentic HIV-1 Env expression plasmid into 293FT cells. HIV-1 Luc viruses produced were inoculated into MT-4 cells in the presence of BMMP, and viral infectivity was monitored by a luciferase reporter assay. Luciferase expression was inhibited in a BMMP dose-dependent manner in cells infected with the HIV-1 Env-pseudotyped Luc virus, indicating that BMMP inhibited the early stage of the HIV-1 life cycle (Fig. 5A). However, when VSV-G-pseudotyped Luc virus was used, a dose-dependent reduction was similarly observed. When HIV-1 (NL43 strain) expressing luciferase was pseudotyped with VSV-G and used in this assay, the luciferase activity driven by the LTR promoter was similarly reduced in the presence of BMMP, suggesting that BMMP did not inhibit the stage of HIV entry (e.g., attachment and membrane fusion processes) but the stage of postentry (e.g., uncoating) (Fig. 5A). The Env-independent infectivity reduction was confirmed when HIV-1 Luc viruses were inoculated into 293FT and 293FT-CD4 cells (Fig. 5B). We examined whether BMMP also blocked the postentry stage of SIV. Interestingly, single-round infection assays with luciferase-expressing SIVmac239 vectors which were pseudotyped with VSV-G protein showed no inhibition of luciferase expression (Fig. 5B). No reduction in luciferase expression was also observed when luciferase-expressing pseudotyped MLV was used (data not shown). These data suggest that BMMP specifically inhibits HIV replication postentry but not those of other retroviruses, such as SIV and MLV.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of HIV-1 replication postentry. (A) Single-round infection assays in MT-4 cells. 293FT cells were cotransfected with pHIVgag-pol (derived from HXB2 strain), pLenti-luciferase, pRevpac, and either a plasmid expressing HIV-1 Env (middle) or a plasmid expressing VSV-G (top). HIV-1 (NL43 strain) expressing luciferase was similarly pseudotyped with VSV-G protein (bottom). Following incubation, the culture supernatants were recovered and were subsequently inoculated into MT-4 cells with increasing doses of BMMP. (B) Single-round infection assays in 293FT and 293FT-CD4 cells. HIV-1 vectors containing the luciferase gene were similarly pseudotyped with HIV-1 Env (middle) or VSV-G protein (top). Luciferase-expressing SIVmac was pseudotyped with VSV-G protein by cotransfection (bottom). Viruses produced were subsequently inoculated into 293FT (top and bottom) or 293FT-CD4 (middle) cells with 5 and 25 μM BMMP. Viral infectivity was assessed by luciferase reporter assays. Data were shown as means with standard deviations from 3 to 6 independent experiments in panels A and B. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (C) Quantitative PCR. MT-4 cells were infected with HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) and incubated in the presence of BMMP. DNA was isolated at 4 or 24 h postinfection and subjected to quantitative PCR for HIV cDNA. Reverse transcripts generated at the early and late phases of HIV reverse transcription were amplified from the DNA isolated at 4 and 24 h postinfection, respectively. The integrated viral genome was amplified as Alu-LTR transcripts from the DNA isolated at 24 h postinfection. EFV (200 nM) was used as positive controls. Three independent infections were performed, and quantitative PCR was carried out in triplicate with each infection sample. Representative data were shown with the means and standard deviations. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

To confirm the postentry block prior to particle production, we isolated cellular DNA from MT-4 cells infected with HIV-1 (HXB2 strain) that were treated with BMMP. Then, we quantified early reverse transcripts of HIV (corresponding to the strong-stop DNA), late reverse transcripts of HIV, and integrated HIV DNA by PCR. When normalized to the level of β-globin DNA (internal control), the levels of the early and late reverse transcripts and of the integrated proviral DNA were reduced, as observed for cells treated with 200 nM efavirenz controls (Fig. 5C). However, RT enzymatic activity was not affected by BMMP when examined in in vitro assays (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that BMMP blocks the early stage of the HIV-1 life cycle, preventing the completion of reverse transcription.

Mapping of Gag domain targeted by BMMP.

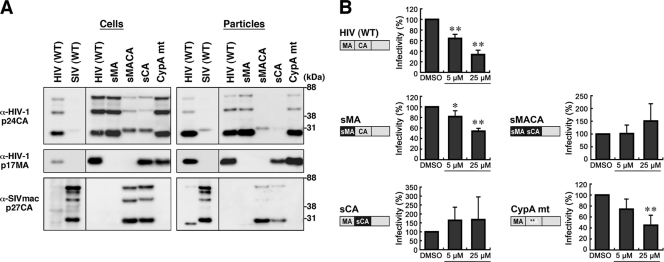

To map the HIV Gag domain responsible for the postentry block by BMMP, a series of chimeric Gag constructs between HIV-1 and SIVmac239 were made in the context of pHIVgag-pol. HIV-1 MA, MACA, and CA were replaced by SIV MA, MACA, and CA, respectively (referred to as sMA, sMACA, and sCA, respectively). These Gag/Gag-Pol expression plasmids were cotransfected with pRevpac and pLenti-luciferase vector, and viruses were pseudotyped with VSV-G protein. Western blotting using anti-HIV-1 p17MA and p24CA and anti-SIVmac p27CA antibodies revealed that, although the anti-HIV-1 p24CA antibody that we used was cross-reactive with SIV CA, each domain of Gag was replaced in the chimeric constructs and virus particles were produced at levels largely similar to that of the wild type of HIV-1 Gag construct (Fig. 6A). Single-round infection assays with these Gag chimeras revealed that BMMP inhibited viral infection postentry only when HIV-1 CA was present in the constructs (Fig. 6B). Thus, our data indicated that BMMP inhibited the early stage of HIV-1 replication in a CA-specific and species-specific manner. These phenotypes resemble those observed for the CA-specific retroviral restriction imposed by a host factor, tripartite motif protein 5 (TRIM5) (30). HIV-1 CA is known to bind a host factor, CypA, likely through amino acids G89 and P90 in the exposed loop of CA (15, 16). This binding facilitates the early stage of HIV-1 replication prior to reverse transcription (9). Interestingly, HIV/SIV chimera studies have shown that the CypA-binding site overlaps with the determinants for species-specific restriction (30, 34). Thus, we made an HIV-1 Gag construct containing amino acid substitutions G89A and P90A in the CypA-binding loop of CA (referred to as CypA mt) and tested the sensitivity to BMMP. The CypA mt did not display the resistance to BMMP (Fig. 6B), suggesting that HIV-1 inhibition by BMMP was not linked to the CypA binding or TRIM5. No firm conclusions were drawn from mapping experiments using Gag chimeras within CA, i.e., N- and C-terminal domains (NTD and CTD), since the CTD mutant showed a lower yield of particle production (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Mapping of Gag domain responsible for inhibition. (A) Intracellular Gag expression and particle production. 293FT cells were cotransfected with pHIVgag-pol expressing chimeric Gag, pLenti-luciferase, pRevpac, and a plasmid expressing VSV-G, and virus particles produced were purified by ultracentrifugation. Cells and particles were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HIV-1 p24CA and p17MA and anti-SIVmac p27CA antibodies. (B) Single-round infection assays with the Gag domain chimeras and Gag mutants with amino acid substitutions. The corresponding domain of SIVmac Gag (black) was introduced into HIV-1 Gag background (gray), and the resultant chimera was referred to as “s” plus the name of the corresponding domain of SIVmac. WT, wild type; sMA, HIV containing replacement of MA with SIV MA; sMACA, HIV containing replacement of MACA with SIV MACA; sCA, HIV containing replacement of CA with SIV CA. CypA mt represents HIV with amino acid substitutions G89A and P90A in the CypA-binding loop of CA NTD (denoted by asterisks). Following infection, the cell culture was incubated in the presence of 5 and 25 μM BMMP. Viral infectivity was monitored by luciferase reporter assays. Data were shown as means with standard deviations from 4 to 6 independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Disassembly of HIV capsid core by BMMP.

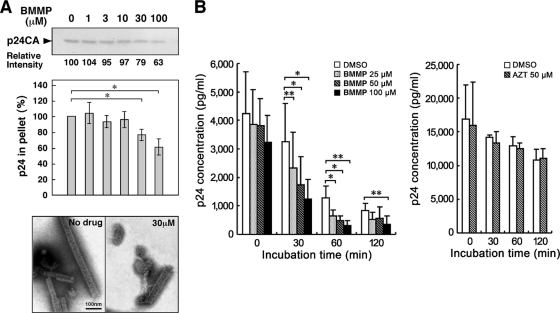

The chimera experiments showed that the CA domain is critical for the inhibitory effect of BMMP on the early stage of HIV-1 replication. Thus, we examined whether BMMP affects CA-CA interaction using purified CA. An in vitro assembly reaction with purified HIV-1 CA was employed to test if BMMP disrupted CA-CA interactions. In vitro assembly reaction of CA has shown it to produce tubular structures representing the mature CA capsid structure (17, 36). We added BMMP to the in vitro assembly reaction with 100 μM HIV-1 CA, and resultant CA assembly products were observed by electron microscopy (Fig. 7A). For quantitative analysis, the resultant CA assembly products were recovered by ultracentrifugation and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The levels of the CA assembly products were reduced when BMMP was added at a concentration higher than 30 μM, corresponding to approximately a 1:3 molar ratio to CA (Fig. 7A). These data suggest that BMMP targets HIV-1 CA and leads to the destabilization of the viral capsid core, since our previous findings indicated that BMMP did not block particle release (Fig. 4) but did block the HIV-1 infection postentry (Fig. 5).

Fig. 7.

HIV-1 mature capsid disassembly and in vitro assembly assays. (A) In vitro assembly reaction with purified HIV-1 CA. Purified HIV-1 CA protein (100 μM) was incubated with various doses of BMMP at 37°C for 60 min in buffer at high salt concentration. All samples included 1% DMSO. Assembly products were recovered by centrifugation and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. The band intensities were semiquantified by ImageJ software. For quantification, the pelleted products were subjected to p24CA antigen capture ELISA. Data were shown as means with standard deviations from 3 independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. Assembly products were also negatively stained and examined by electron microscopy. Micrographs were shown at the same magnification. Bar = 100 nm. (B) Cell-free assays for HIV-1 uncoating. HIV-1 mature capsids were isolated through a 1% Triton X-100 layer as described previously (3). The HIV-1 cores were incubated with various doses of BMMP at 37°C up to 120 min. For comparison, the cores were similarly incubated with 50 μM AZT. All samples included 1% DMSO. Residual intact cores were recovered by ultracentrifugation and quantified by p24CA antigen capture ELISA. Data were shown as means with standard deviations from 4 independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

To test this possibility in a more relevant assay, we adopted cell-free disassembly assays using purified HIV-1 mature capsid core. To this end, we isolated HIV-1 capsid cores by ultracentrifugation through a Triton X-100 layer, as described previously (3). HIV-1 cores are known to disassemble when incubated at 37°C. We examined if BMMP accelerated the rate of core disassembly. The HIV-1 cores were incubated with BMMP at 37°C up to 120 min, and residual intact cores were recovered by centrifugation. When quantified by p24CA antigen capture ELISA, intact cores were found to be reduced in a time-dependent manner in the presence of DMSO (as control), consistent with previous reports (3). A similar level of reduction was observed in the presence of AZT. However, addition of BMMP accelerated a reduction in intact cores in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7B). Altogether, our data indicated that BMMP disrupted HIV-1 capsid cores through targeting CA.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we employed a yeast membrane-associated two-hybrid assay to monitor the HIV Gag-Gag interactions and established cell-based screening assays for drugs targeting Gag assembly. We screened a commercially available chemical library and found BMMP, which inhibits HIV-1 replication in PBMC culture. Our single-round infection analysis indicated that BMMP primarily targets HIV-1 CA and inhibits HIV infection postentry but not particle production (Fig. 4 to 6). In vitro CA assembly/disassembly assays showed that BMMP facilitated HIV-1 core disassembly (Fig. 7). Collectively, it is conceivable that BMMP may bind to mature capsid structure and facilitate disassembly of the capsid, leading to premature earlier uncoating and failure of postentry events (e.g., reverse transcription and integration). The mechanism of action may be akin to the block of HIV-1 entry by rTRIM5α (30).

Previous studies have reported inhibitors that target HIV-1 Gag assembly and/or Gag processing. 3-O-(3′,3′-Dimethylsuccinyl)betulinic acid, known as PA-457 or Bevirimat (molecular weight, 584), binds to the Gag CA-SP1 cleavage site and inhibits proteolytic conversion of Gag precursors to the mature form of p24CA (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50] = 10 nM) (1, 2, 21). Inhibition of Gag processing has also been observed with a distinct chemical class of compound, 1-[2-(4-tert-butylphenyl)-2-(2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-2-ylamino)ethyl]-3-(trifluoromethyl)pyridin-2(1H)-one (molecular weight, 454) (7). The hallmark of these inhibitors is incomplete Gag processing and accumulation of processing intermediates (e.g., CA-SP1) in virions, resulting in the loss of viral infectivity. These compounds do not inhibit Gag assembly. Since our BMMP did not show alteration in overall patterns of Gag processing (Fig. 4A), it is unlikely that BMMP shares the inhibition mechanisms with above inhibitors.

Inhibitors of HIV capsid assembly have been extensively screened by several approaches. In silico screening from public chemical libraries has identified N-(3-chloro-4-methylphenyl)-N′-{2-[({5-[(dimethylamino)-methyl]-2-furyl}-methyl)-sulfanyl]ethyl}-urea, termed CAP-1 (32), which binds to HIV-1 CA NTD (Kd [dissociation constant] = 800 μM), resulting in the inhibition of the correct interaction of hexameric units of CA NTD with dimeric units of CA CTD, essential for a high order of CA assembly (20). CAP-1 reduced the infectivity of progeny HIV but did not inhibit viral entry or particle production (32). Phage display biopanning has also been employed and has isolated a 12-mer peptide, termed CAI, which binds to HIV-1 CA CTD (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50] = 3 to 4 μM) and inhibits CA capsid formation in vitro (Kd = 15 μM) (5, 29, 33). However, CAI did not inhibit HIV replication in cell culture because of the lack of cell permeability. In a subsequent study, CAI has been converted to a cell-penetrating peptide (termed NYAD-1) by stabilizing the α-helical structure of CAI with a hydrocarbon staple, leading to a marked improvement of Kd (<1 μM) (38). Surprisingly, the study revealed that, besides inhibiting the particle production, NYAD-1 disrupted the mature core formation and inhibited the early stage of HIV-1 in single-round infection assays, suggesting that NYAD-1 may affect the uncoating stage of the HIV life cycle through a mechanism similar to that of BMMP.

The difference between BMMP and CAI/NYAD-1 is that BMMP does not affect HIV-1 particle production or maturation steps. This is possibly because BMMP inhibits CA-CA interactions more efficiently than Gag-Gag interactions. Importantly, BMMP is not a peptide but a low-molecular-weight compound (molecular weight, 273.38), which is chemically and physically stable. It should be possible to chemically modify the BMMP structure to potentiate its biochemical and biological activities. The advantage of BMMP is that, due to its low molecular weight, the derivatives could retain cell membrane permeability unless large chemical groups are attached to the core structure.

A low-molecular-weight Gag inhibitor, PF74, previously screened from a chemical library by a high-throughput single-round infection assay (6), has been characterized by a more recent study, in which PF74 selectively inhibited HIV-1 (27). PF74 destabilized HIV-1 capsids and inhibited the postentry events, similarly to BMMP, but at low-micromolar concentrations. However, BMMP is distinct from PF74 in that the CypA-binding loop is not involved in the viral susceptibility to BMMP (Fig. 6B). Also, BMMP did not reduce the viral infectivity when the virion was exposed to BMMP (data not shown). Therefore, BMMP may have a potential to serve as a lead compound for the development of anti-HIV drugs bearing a novel mechanism of action.

Although BMMP showed anti-HIV activity, it still needs to be improved to lower the IC50. We suggest that comprehensive studies on structural analogues of BMMP would be informative to understand the structure-function relationship of BMMP. Also, analysis of BMMP-resistant viruses and X-ray cocrystallography should provide insights into the mechanism of action that direct the way to potentiate the BMMP derivatives.

Recent cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray structure analysis have revealed the intermolecular interfaces between NTD and CTD in the three-dimensional hexameric structures of full-length CA (18, 24). It has been strongly suggested that multiple CA interactions, including NTD-NTD, CTD-CTD, and NTD-CTD, are essential for the constitution of mature HIV capsid. It is possible that some of the interfaces may not be formed in Gag-Gag interactions. CAI, similar to CAP-1, may inhibit CA assembly possibly by disrupting the formation of the NTD-CTD interface (18). Thus, these studies may provide a rationale for developing inhibitors that target the molecular interface of CA that specifically appears during a higher order of oligomerization. We suggest that viral capsid assembly/disassembly is an attractive therapeutic target and that such capsid inhibitors would help understand the regulation of postentry events.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a Human Science grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adamson C. S., et al. 2006. In vitro resistance to the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 maturation inhibitor PA-457 (Bevirimat). J. Virol. 80:10957–10971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adamson C. S., Waki K., Ablan S. D., Salzwedel K., Freed E. O. 2009. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to protease inhibitors on evolution of resistance to the maturation inhibitor bevirimat (PA-457). J. Virol. 83:4884–4894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aiken C. 2009. Cell-free assays for HIV-1 uncoating. Methods Mol. Biol. 485:41–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aronheim A., et al. 1994. Membrane targeting of the nucleotide exchange factor Sos is sufficient for activating the Ras signaling pathway. Cell 78:949–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartonova V., et al. 2008. Residues in the HIV-1 capsid assembly inhibitor binding site are essential for maintaining the assembly-competent quaternary structure of the capsid protein. J. Biol. Chem. 283:32024–32033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blair W. S., et al. 2005. A novel HIV-1 antiviral high throughput screening approach for the discovery of HIV-1 inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 65:107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blair W. S., et al. 2009. New small-molecule inhibitor class targeting human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion maturation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:5080–5087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Botstein D. 1997. Yeast as a model organism. Science 277:1259–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Braaten D., Franke E. K., Luban J. 1996. Cyclophilin A is required for an early step in the life cycle of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 before the initiation of reverse transcription. J. Virol. 70:3551–3560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Broder S. 2010. The development of antiretroviral therapy and its impact on the HIV-1/AIDS pandemic. Antiviral Res. 85:1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bukovsky A. A., Weimann A., Accola M. A., Gottlinger H. G. 1997. Transfer of the HIV-1 cyclophilin-binding site to simian immunodeficiency virus from Macaca mulatta can confer both cyclosporin sensitivity and cyclosporin dependence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:10943–10948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Butler S. L., Hansen M. S. T., Bushman F. D. 2001. A quantitative assay for HIV DNA integration in vivo. Nat. Med. 7:631–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Craven R. C., Parent L. J. 1996. Dynamic interactions of the Gag polyprotein. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 214:65–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Forshey B. M., von Schwedler U., Sundquist W. I., Aiken C. 2002. Formation of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 core of optimal stability is crucial for viral replication. J. Virol. 76:5667–5677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Franke E. K., Yuan H. E., Luban J. 1994. Specific incorporation of cyclophilin A into HIV-1 virions. Nature 372:359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gamble T. R., et al. 1996. Crystal structure of human cyclophilin A bound to the amino-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid. Cell 87:1285–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ganser B. K., Li S., Klishko V. Y., Finch J. T., Sundquist W. I. 1999. Assembly and analysis of conical models for the HIV-1 core. Science 283:80–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ganser-Pornillos B. K., Cheng A., Yeager M. 2007. Structure of full-length HIV-1 CA: a model for the mature capsid lattice. Cell 131:70–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Graf Einsiedel H., et al. 2002. Deletion analysis of p16INKa and p15INKb in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 99:4629–4631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kelly B. N., et al. 2007. Structure of the antiviral assembly inhibitor CAP-1 complex with the HIV-1 CA protein. J. Mol. Biol. 373:355–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li F., et al. 2003. PA-457: a potent HIV inhibitor that disrupts core condensation by targeting a late step in Gag processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:13555–13560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morikawa Y. 2003. HIV capsid assembly. Curr. HIV Res. 1:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pauwels R., et al. 1990. Potent and selective inhibition of HIV-1 replication in vitro by a novel series of TIBO derivatives. Nature 343:470–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pornillos O., et al. 2009. X-ray structures of the hexameric building block of the HIV capsid. Cell 137:1282–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roberts N. A., et al. 1990. Rational design of peptide-based HIV proteinase inhibitors. Science 248:358–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sakuragi S., Goto T., Sano K., Morikawa Y. 2002. HIV type 1 Gag virus-like particle budding from spheroplasts of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:7956–7961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shi J., Zhou J., Shah V. B., Aiken C., Whitby K. 2011. Small molecule inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection by virus capsid destabilization. J. Virol. 85:542–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shimizu S., et al. 2007. Inhibiting lentiviral replication by HEXIM1, a cellular negative regulator of the CDK9/cyclin T complex. AIDS 21:575–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sticht J., et al. 2005. A peptide inhibitor of HIV-1 assembly in vitro. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12:671–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stremlau M., et al. 2006. Specific recognition and accelerated uncoating of retroviral capsids by the TRIM5alpha restriction factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:5514–5519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Suzuki S., et al. 2010. Peptide HIV-1 integrase inhibitors from HIV-1 gene products. J. Med. Chem. 53:5356–5360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tang C., et al. 2003. Antiviral inhibition of the HIV-1 capsid protein. J. Mol. Biol. 327:1013–1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ternois F., Sticht J., Duquerroy S., Krausslich H. G., Rey F. A. 2005. The HIV-1 capsid protein C-terminal domain in complex with a virus assembly inhibitor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12:678–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Towers G. J., et al. 2003. Cyclophilin A modulates the sensitivity of HIV-1 to host restriction factors. Nat. Med. 9:1138–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Urano E., et al. 2008. Substitution of the myristoylation signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Pr55Gag with the phospholipase C-delta1 pleckstrin homology domain results in infectious pseudovirion production. J. Gen. Virol. 89:3144–3149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. von Schwedler U. K., et al. 1998. Proteolytic refolding of the HIV-1 capsid protein amino-terminus facilitates viral core assembly. EMBO J. 17:1555–1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Westby M., Nakayama G. R., Butler S. L., Blair W. S. 2005. Cell-based and biochemical screening approaches for the discovery of novel HIV-1 inhibitors. Antiviral Res. 67:121–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang H., et al. 2008. A cell-penetrating helical peptide as a potential HIV-1 inhibitor. J. Mol. Biol. 378:565–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]