Abstract

In 18 male healthy subjects, artesunate (200 mg)-azithromycin (1,500 mg) daily for 3 days was found to be well tolerated, with only mild gastrointestinal disturbances reported. The pharmacokinetic properties of artesunate-azithromycin given in combination are comparable to those of the drugs given alone. Artesunate and its major active metabolite, dihydroartemisinin, are responsible for most of the ex vivo antimalarial activity, with a delayed contribution by azithromycin.

TEXT

Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are currently recommended for the first-line treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria, worldwide (25). The two risk groups most vulnerable to malaria are young children and pregnant women, who are immunosuppressed and particularly at risk for severe disease (26). In pregnant women, limited safety and pharmacological data are available on the use of ACTs, particularly during the first trimester. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that quinine combined with the antibiotic clindamycin be given for 7 days during the first trimester and, if quinine-clindamycin is either unavailable or fails, an ACT is indicated (25). Historically, 7-day daily regimens are limited by poor compliance in an outpatient setting (9). For the second and third trimesters, WHO recommends artesunate (AS)-clindamycin.

However, a drawback in using clindamycin is its short half-life of 2.4 h (10), which necessitates repeated dosing every 12 h, which may affect compliance and thus effectiveness (20). Unlike clindamycin, the antibiotic azithromycin (AZ) possesses wider therapeutic applications (8) and has pharmacokinetic properties that are characterized by more extensive tissue distribution, prolonged phagocyte concentrations, and a longer elimination half-life of about 50 h (1, 14). These favorable features allow once-daily dosing with AZ compared with multiple daily dosing with clindamycin. Recently, 3-day courses of quinine with either 1,000 or 1,500 mg AZ were shown to be well tolerated and effective in curing multidrug-resistant P. falciparum malaria in adults (12). AZ also has a good safety profile in children and pregnant women (6, 21).

Because of AZ's favorable pharmacokinetic properties, artesunate (AS) plus AZ may be a suitable ACT during pregnancy. In vitro studies have shown dihydroartemisinin (DHA), the active metabolite of the prodrug AS, combined with AZ to be additive (17) tending to synergistic (16) against multidrug-resistant P. falciparum strains. Recent studies of AS-AZ have shown good efficacy in the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria using 3-day regimens of 200 mg AS daily with either 1,000 mg AZ (cure rate, 89%) (15) or 1,500 mg AZ (cure rates, >92%) (15, 24). The AS-AZ combinations are far more effective than monotherapy, with recrudescence rates of between 10% and 80% with 3- to 5-day courses of AS alone (4) and 67% with 1,000 mg/day AZ for 3 days (7). Similarly, the addition of AZ (1,000 mg daily for 2 days) to 1,500 mg sulfadoxine and 75 mg pyrimethamine for the treatment of malaria during pregnancy increased the cure rate from 71% to 92% compared with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine alone (11).

Despite the proven efficacy of AS and high-dose AZ in treating malaria, there are no data on the safety and pharmacokinetics of the ACT in healthy subjects to support its use in patients. The present study investigated the tolerability, pharmacokinetic properties, and ex vivo antimalarial activity of a 3-day regimen of 200 mg AS plus 1,500 mg AZ in 18 healthy male Vietnamese subjects. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Review and Scientific Board of Military Hospital 108 and the Australian Defense Human Research Ethics Committee (ADHREC no. 496/07).

The subjects were coadministered 200 mg AS (Traphaco Joint Stock Company, Hanoi, Vietnam; each tablet contained 50 mg AS) and 1,500 mg AZ (Zitromax; Pfizer Italia, Latina, Italy; each tablet contained 500 mg AZ) daily for 3 days. The ACT was administered to the subjects with 240 ml water after an overnight fast (no food for at least 8 h). Blood chemistry tests (complete blood count, liver function tests, urea, and creatinine) were performed before treatment and repeated at 2 weeks after the last drug administration. Adverse events were assessed daily by a physician with the question “How do you feel since you took the last artesunate-plus-azithromycin tablets?” followed by prespecified questions about specific symptoms, which included loose stools, nausea, abdominal pain, headache, insomnia, tiredness, and dizziness. Electrocardiograms were recorded at 0 h, immediately before and 2 h after the last dose, and at day 7 following the last drug administration.

Venous blood samples (7 ml) were collected with an indwelling cannula within 0.5 h (baseline) before the last dose and at 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 h after drug administration. Subsequent blood samples were collected by venipuncture at days 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14 after the last dose. For measurement of AS and DHA in plasma, blood samples were drawn into sodium fluoride-potassium oxalate blood collection tubes to prevent hydrolysis of AS by plasma esterases (2). For serum AZ analysis, blood samples were drawn into plain tubes. Blood samples were centrifuged at 1,400 × g for 10 min, and the separated plasma or serum samples were stored at −80°C until transported on dry ice to Australia for drug analysis, which was carried out within 12 months of collection.

Plasma concentrations of AS and DHA and serum concentrations of AZ were measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) (see the supplemental material). The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of AS was 1 ng/ml, with an interassay precision of analysis (percent coefficient of variation [CV]) for AS of 6.6% at 1 ng/ml, 4.3% at 100 ng/ml, and 3.8% at 500 ng/ml (n = 18). The LLOQ for DHA was 1 ng/ml, with an interassay precision for DHA of 5.8% at 1 ng/ml, 3.8% at 100 ng/ml, and 4.2% at 2,000 ng/ml (n = 18). For AZ, the LLOQ was 5 ng/ml, with an interassay precision for AZ of 1.9% at 5 ng/ml, 0.9% at 500 ng/ml, and 2.3% at 2,000 ng/ml (n = 3). Pharmacokinetic parameters (peak concentration [Cmax], time to reach maximum concentration [Tmax], area under the concentration-time curve from day 2 to last data point [AUCday 2→last] and day 2 to infinity [AUCday 2→∞], and terminal half-life [t1/2]) were determined from the concentration-time data using noncompartmental methods. The ex vivo antimalarial activity of AS-AZ was assessed by bioassay, which involves culturing malaria parasites in vitro in the presence of subjects' serum samples collected after the last administration of the ACT using the method described by Nagelschmitz et al. (13), with minor modifications. They were as follows: (i) the in vitro drug susceptibilities of the multidrug (atovaquone, chloroquine, quinine, and pyrimethamine)-resistant TM90-C2B line of P. falciparum to AS, DHA, and AZ and the subjects' serum samples were determined in parallel; (ii) 50 μl of human serum was used, so the final concentration of serum/plasma in the well was 50%; and (iii) an incubation period of 96 h of drug exposure was applied due to AZ's slower parasiticidal action (22, 27). Fifty percent inhibitory concentration (IC50) and 50% inhibitory dilution (ID50) values were defined as the drug concentrations and dilutions that produced a 50% inhibition of uptake of tritiated hypoxanthine by intraerythrocytic malaria parasites compared to drug-free serum samples (controls). The bioassay data are reported as activities equivalent to a known concentration of DHA, which were estimated by multiplying the ID50 of the subject's serum samples after AS-AZ administration by the IC50 of DHA (expressed as ng/ml).

The subjects' mean (±standard deviation) age was 20.7 (1.6) years, with a mean weight of 58.8 (2.6) kg. AS-AZ did not appear to cause any clinically significant changes in hematological and biochemical indices, with values within the normal range before and after drug administration (see the supplemental material). Electrocardiograms did not change as a result of AS-AZ administration (data not shown). After the first dose of AS-AZ, 11% (2/18) of subjects had abdominal pain and 61% (11/18) had loose stools. These adverse events were again seen after the second dose, with the frequency of abdominal pain and loose stools increasing to 22% and 67%, respectively. However, no gastrointestinal (GI) disturbances were reported by the subjects after the third dose of AS-AZ. On each of the first 2 days of drug administration, GI disturbances were mild (discomfort not affecting daily activities and requiring no medical intervention) in severity and transient, with most adverse events occurring between 1 and 6 h after dosing. In the subjects with abdominal pain, the discomfort lasted between 0.5 and 1 h. It is assumed that the high dose of AZ was responsible for the GI adverse events, as this class of compound is associated with causing GI disturbances and those disturbances appear to be dose related (18), which is not the case for AS (5, 19). The high frequency of GI disturbances in the healthy subjects was unexpected, as a lower frequency of abdominal pain (7.7%) and loose stools (3.8%) was reported by malaria patients treated with the same AS-AZ regimen (24). With the exception of GI disturbances, no other adverse events were reported by the subjects in the present study.

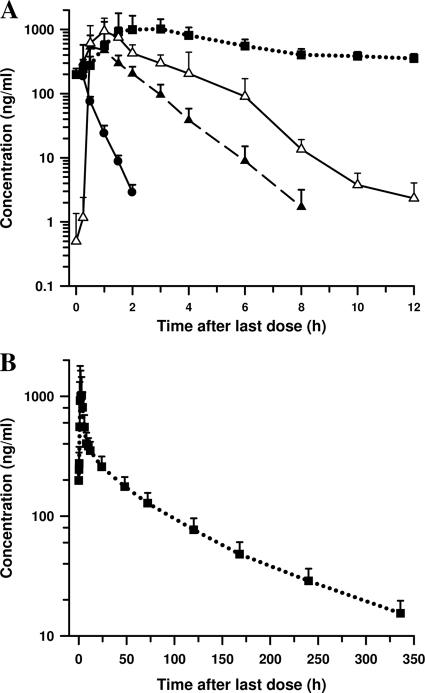

The mean plasma concentration-time profiles of AS and DHA and serum concentration-time profile of AZ after a 3-day course of AS-AZ are shown in Fig. 1. The pharmacokinetic properties of the drugs are summarized in Table 1. The mean Cmax and AUC values of AS were markedly higher in our subjects than in a previous study in Vietnamese subjects by Diem Thuy et al. (5) (Cmax, 197 versus 67 ng/ml; AUC, 96 versus 67 ng · h/ml) given the same daily dose of AS. The prodrug was rapidly eliminated, with a mean t1/2 of 0.26 h, and by 2 h after drug administration, 33% (6/18) of subjects had AS concentrations below the LLOQ. AS was rapidly and extensively hydrolyzed to DHA, with measurable concentrations (>1 ng/ml) in all subjects at 0.25 h after dosing. The Cmax, AUC, and t1/2 values of DHA in our participants were similar to those reported by Diem Thuy et al. (5) (Cmax, 644 versus 632 ng/ml; AUC, 933 versus 1,158 ng · h/ml; t1/2, 0.83 versus 0.81 h). After adjusting for dose differences, the pharmacokinetics of AS and DHA were also comparable with values obtained in healthy Thai subjects administered 100 mg AS (23).

Fig. 1.

Mean (standard deviation) concentrations of AS, DHA, and AZ. (A) Profiles of plasma concentrations of AS (●) and DHA (▴) and serum concentrations of azithomycin (■) versus time after the last dose of a 3-day course of daily 200-mg AS and 1,500-mg AZ in 18 healthy Vietnamese subjects. The ex vivo pharmacodynamic antimalarial activity profile of subjects' serum DHA equivalent concentrations (▵) was estimated by bioassay using the TM90-C2B line of P. falciparum. (B) Profile of serum concentrations of AZ (■) versus time from day 2 to day 16 after commencement of treatment.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of AS, DHA, and AZ in 18 healthy Vietnamese subjects after the last dose of a 3-day course of daily 200-mg AS and 1,500-mg AZ

| Pharmacokinetic parameter | Mean ± SD for drug: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| AS (plasma concn) | DHA (plasma concn) | AZ (serum concn) | |

| Cmax (ng/ml) | 197 ± 105 | 644 ± 221 | 1,624 ± 626 |

| Tmax (h) | 0.38 ± 0.30 | 0.75 ± 0.45 | 2.5 ± 1.0 |

| AUCday 2→last (ng · h/ml) | 90 ± 45 | 990 ± 211 | 32,300 ± 6,600 |

| AUCday 2→∞ (ng · h/ml) | 96 ± 43 | 993 ± 212 | 34,200 ± 7,100 |

| t1/2 (h) | 0.26 ± 0.17 | 0.83 ± 0.12 | 87.4 ± 5.5 |

AZ was rapidly absorbed, with maximum serum drug concentrations of 1,624 ng/ml attained at about 2.5 h after the last dose. Thereafter, serum concentrations of AZ fell rapidly and biphasically, with a mean t1/2 of 87.4 h. The Cmax, AUC, and t1/2 values of AZ obtained in our subjects are in accord with those reported by Cook et al. (3) following a 3-day regimen of daily 1,000-mg AZ alone in healthy subjects, after adjusting for dose and body weight differences between the 2 studies.

Based on IC50s (geometric mean [95% confidence interval]), AS (0.47 ng/ml [0.35 to 0.63, n = 14]) and DHA (0.30 ng/ml [0.23 to 0.38, n = 18]) were markedly more active than AZ (2,971 ng/ml [2,162 to 4,082, n = 14]) in inhibiting the TM90-C2B line. The IC50s of DHA (0.30 ng/ml versus 0.53 ng/ml) and AZ (2,971 ng/ml versus 2,570 ng/ml) were comparable to that obtained by Noedl et al. (16) against fresh clinical P. falciparum isolates from Thailand. The selection to estimate DHA equivalent concentrations by bioassay was based on AS and DHA having similar IC50s and on the finding that AZ is markedly less active than the artemisinins, in vitro.

The mean DHA equivalent concentrations obtained by bioassay were higher than the composite AS and DHA concentrations measured by LC/MS/MS from 1 h to 10 h after the last dose of the ACT (Fig. 1). At 8 h, DHA concentrations were below the in vitro MIC for P. falciparum of <2 ng/ml, with physiological concentrations of AZ remaining to exert its parasiticidal effect. The extra antimalarial activity as shown by the higher DHA equivalent concentrations is suggestive of AZ's delayed death effect in inhibiting the next generation of parasites (22). This observation is further supported by a marked reduction in inhibitory concentrations of AZ, ranging between 28-fold and 522-fold in 5 P. falciparum lines, with different levels of chloroquine sensitivity, between the first and second asexual erythrocytic cycles (22, 27).

In conclusion, the 3-day regimen of 200 mg AS daily plus 1,500 mg AZ used in clinical studies (15, 24) was well tolerated in healthy Vietnamese subjects, with the exception of only mild and transient GI disturbances. The ex vivo antimalarial activity of the subjects' serum concentrations after AS-AZ treatment revealed that most of the potency in killing a multidrug-resistant P. falciparum line was due to the artemisinins, with a noticeable contribution by AZ. The findings of this study suggest that AS-AZ is worthy of further investigations in pregnant women and young children to assess its potential as an alternative ACT for the treatment of malaria in these special risk groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out under the auspices of the Vietnam Australia Defense Malaria Project, a defense cooperation between the Vietnam People's Army and the Australian Defense Force. We thank the Vietnam People's Army Department of Military Medicine for supporting the study and the financial sponsor, the Australian Defense Force International Policy Division.

We are grateful to Russell Addison at TetraQ, Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Brisbane, for developing the LC/MS/MS methods for AS, DHA, and AZ and Thomas Travers for carrying out the drug analysis. We thank Kerryn Rowcliffe for in vitro analysis and the Australian Red Cross Blood Service (Brisbane) for providing human erythrocytes and serum for the in vitro cultivation of a P. falciparum line. We thank Le Ngoc Anh for administrative and logistic support.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Defense Force, Joint Health Command, or any extant policy.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 5 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amsden G. W., Gray C. L. 2001. Serum and WBC pharmacokinetics of 1500 mg of azithromycin when given either as a single dose or over a 3 day period in healthy volunteers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Batty K. T., et al. 1996. Selective high-performance liquid chromatographic determination of artesunate and alpha- and beta-dihydroartemisinin in patients with falciparum malaria. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Appl. 677:345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cook J. A., Randinitis E. J., Bramson C. R., Wesche D. L. 2006. Lack of a pharmacokinetic interaction between azithromycin and chloroquine. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 74:407–412 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Vries P. J., Dien T. K. 1996. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutic potential of artemisinin and its derivatives in the treatment of malaria. Drugs 52:818–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Diem Thuy L. T., Ngoc Hung L., Danh P. T., Na-Bangchang K. 2008. Absence of time-dependent artesunate pharmacokinetics in healthy subjects during 5-day oral administration. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 64:993–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dolecek C., et al. 2008. A multi-center randomised controlled trial of gatifloxacin versus azithromycin for the treatment of uncomplicated typhoid fever in children and adults in Vietnam. PLoS One 3:e2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dunne M. W., et al. 2005. A multicenter study of azithromycin, alone and in combination with chloroquine, for the treatment of acute uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in India. J. Infect. Dis. 191:1582–1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duran J. M., Amsden G. W. 2000. Azithromycin: indications for the future? Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 1:489–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fungladda W., et al. 1998. Compliance with artesunate and quinine + tetracycline treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Thailand. Bull. World Health Organ. 76(Suppl. 1):59–66 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gatti G., et al. 1993. Comparative study of bioavailabilities and pharmacokinetics of clindamycin in healthy volunteers and patients with AIDS. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1137–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kalilani L., et al. 2007. A randomized controlled pilot trial of azithromycin or artesunate added to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine as treatment for malaria in pregnant women. PLoS One 2:e1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller R. S., et al. 2006. Effective treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria with azithromycin-quinine combinations: a randomized, dose-ranging study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 74:401–406 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nagelschmitz J., et al. 2008. First assessment in humans of the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and ex vivo pharmacodynamic antimalarial activity of the new artemisinin derivative artemisone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3085–3091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Najib N. M., et al. 2001. Bioequivalence assessment of Azomycin (Julphar, UAE) as compared to Zithromax (Pfizer, USA)—two brands of azithromycin—in healthy human volunteers. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 22:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Noedl H., et al. 2006. Azithromycin combination therapy with artesunate or quinine for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in adults: a randomized, phase 2 clinical trial in Thailand. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:1264–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Noedl H., et al. 2007. In vitro antimalarial activity of azithromycin, artesunate, and quinine in combination and correlation with clinical outcome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:651–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ohrt C., Willingmyre G. D., Lee P., Knirsch C., Milhous W. 2002. Assessment of azithromycin in combination with other antimalarial drugs against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2518–2524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Periti P., Mazzei T., Mini E., Novelli A. 1993. Adverse effects of macrolide antibacterials. Drug Saf. 9:346–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Price R. N. 2000. Artemisinin drugs: novel antimalarial agents. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 9:1815–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ramharter M., et al. 2005. Artesunate-clindamycin versus quinine-clindamycin in the treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40:1777–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sarkar M., Woodland C., Koren G., Einarson A. R. 2006. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to azithromycin. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 6:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sidhu A. B., et al. 2007. In vitro efficacy, resistance selection, and structural modeling studies implicate the malarial parasite apicoplast as the target of azithromycin. J. Biol. Chem. 282:2494–2504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Teja-Isavadharm P., et al. 2001. Comparative pharmacokinetics and effect kinetics of orally administered artesunate in healthy volunteers and patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65:717–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thriemer K., et al. 2010. Azithromycin combination therapy for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Bangladesh: an open-label randomized, controlled clinical trial. J. Infect. Dis. 202:392–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. WHO 2010. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria, 2nd ed World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 26. WHO 2010. International travel and health. Chapter 7. Malaria. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yeo A. E., Rieckmann K. H. 1995. Increased antimalarial activity of azithromycin during prolonged exposure of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Int. J. Parasitol. 25:531–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.