Abstract

Antimicrobial residues found in municipal wastewater may increase selective pressure on microorganisms for development of resistance, but studies with mixed microbial cultures derived from wastewater have suggested that some bacteria are able to inactivate fluoroquinolones. Medium containing N-phenylpiperazine and inoculated with wastewater was used to enrich fluoroquinolone-modifying bacteria. One bacterial strain isolated from an enrichment culture was identified by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis as a Microbacterium sp. similar to a plant growth-promoting bacterium, Microbacterium azadirachtae (99.70%), and a nematode pathogen, “M. nematophilum” (99.02%). During growth in medium with norfloxacin, this strain produced four metabolites, which were identified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses as 8-hydroxynorfloxacin, 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin, desethylene norfloxacin, and N-acetylnorfloxacin. The production of the first three metabolites was enhanced by ascorbic acid and nitrate, but it was inhibited by phosphate, amino acids, mannitol, formate, and thiourea. In contrast, N-acetylnorfloxacin was most abundant in cultures supplemented with amino acids. This is the first report of defluorination and hydroxylation of a fluoroquinolone by an isolated bacterial strain. The results suggest that some bacteria may degrade fluoroquinolones in wastewater to metabolites with less antibacterial activity that could be subject to further degradation by other microorganisms.

INTRODUCTION

A variety of pharmaceuticals, including several fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agents used in human and veterinary medicine, have been detected at low concentrations in wastewater treatment plants and other environmental sites in many countries (16, 23, 30, 50, 55). Understanding the degradation pathways of these drugs and the potential biological activity of the metabolites (48) is important to prevent selection for drug-resistant strains. Solid-phase extraction, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS) have been used to concentrate and detect norfloxacin and other fluoroquinolones in wastewater (11, 33, 47). When fluoroquinolones given to livestock are excreted and the treatment of wastewater is minimal or nonexistent, as in some feed lots and slaughterhouses, fluoroquinolones may be released into river water (47). In contrast, when wastewater is treated by the activated sludge process, much of the fluoroquinolone content is sorbed and cannot be detected (11, 55). Some bacteria with resistance to antibiotics, however, may proliferate in wastewater and transfer resistance genes to other species (30).

The metabolism of fluoroquinolones by environmental brown rot fungi is well understood (51–53), and some metabolic pathways for fluoroquinolones have also been determined for other fungi (40–42). Ring oxidation or hydroxylation is generally the first step in fungal degradation of fluoroquinolones (51, 53). Fluoroquinolones may be defluorinated and hydroxylated by reactive oxygen species, including hydroxyl radicals (46, 54). These radicals may be produced during fungal degradation (51) or by sunlight (19); however, bacterial metabolism of fluoroquinolones has been studied infrequently. Pure cultures of bacteria and mixed cultures from wastewater treatment plants degrade the piperazine moieties of some fluoroquinolones (1, 12, 13). A modified aminoglycoside acetyltransferase from Escherichia coli is responsible for acetylation of fluoroquinolones (28, 43).

It seemed possible that bacteria capable of fluoroquinolone modification or degradation could be isolated from a wastewater treatment plant and that the metabolites produced could be identified to determine the metabolic pathways. By using HPLC, mass spectrometric (liquid chromatography-ESI-MS/MS [LC-ESI-MS/MS]), and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses, it was shown that a norfloxacin-insensitive strain of Microbacterium sp. isolated from wastewater was able to transform norfloxacin to four different metabolites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and media.

Norfloxacin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was prepared as a 10 mg ml−1 stock solution in 40 mM KOH, and N-phenylpiperazine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared as a 100 mg ml−1 stock solution in deionized water. Ascorbic acid and mannitol were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA), and reduced glutathione (GSH), dithiothreitol (DTT), NADH, sodium formate, and thiourea were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

The principal medium used, referred to as OM medium, was composed (per liter) of 1.0 g glucose, 50 mg NH4Cl, 50 mg (NH4)2SO4, 50 mg NaNO3, 10 mg Na2HPO4·7H2O, 8 mg KH2PO4, 100 mg MgSO4·7H2O, 20 mg CaCl2·2H2O, 50 mg BD Difco yeast nitrogen base (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and 20 μg of each trace element (CoCl2·6H2O, CuCl2·2H2O, FeSO4·7H2O, FeCl3·6H2O, H3BO3, MnCl2·4H2O, Na2MoO4, NiCl2·6H2O, and ZnCl2·4H2O). In one experiment, the phosphate concentration of OM medium (96 μM phosphate) was varied from 48 μM to 480 μM to determine the optimum concentration for metabolite production. In another experiment, a single nitrogen source [NH4Cl, (NH4)2SO4, NaNO3, or NaNO2] was used in OM medium at a concentration of 1.0 g liter−1.

Amino acid-supplemented medium contained the same ingredients as OM medium but had Bacto Casamino Acids (BD Biosciences) instead of NH4Cl, (NH4)2SO4, and NaNO3. The concentration of Casamino Acids was 0.05, 0.2, or 2.0 g liter−1 (with the respective media referred to as 0.05 CM medium, 0.2 CM medium, and 2.0 CM medium).

Enrichment cultures and strain isolation.

Enrichment cultures (40 ml) in 250-ml flasks with 100 μg ml−1 N-phenylpiperazine as the sole carbon source or nitrogen source were inoculated with aerobic liquor from a wastewater treatment plant in Little Rock, AR (28). N-Phenylpiperazine is a model compound containing the piperazine moiety, which is important in the antibacterial activity of several fluoroquinolones (5). Cultures were incubated aerobically at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Bacteria were isolated from enrichment cultures by being streaked onto LB-Miller medium (BD Biosciences) with 10 g liter−1 NaCl, 70 mg liter−1 norfloxacin, and 20 g liter−1 agar and incubation at 30°C for 5 days in the dark. Stock cultures were grown on LB agar for 5 days and stored in 20% glycerol at −80°C.

DNA isolation, PCR, and phylogenetic analysis.

Genomic DNA was isolated with a genomic DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories, Solano Beach, CA). The 16S rRNA gene was amplified from isolated genomic DNA by use of Ex Taq polymerase (Takara Bio, Madison, WI) and the universal primers 8F and 1492R (31). PCR products were sequenced at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (Little Rock, AR).

The identification of phylogenetic neighbors was carried out by searches with the BLASTN (2) and megaBLAST (56) programs against the database of the EzTaxon server (http://www.eztaxon.org/) (15). Strains were aligned manually with the nearest sequences obtained from EzTaxon by using the jPHYDIT program (27), and phylogenetic trees were inferred by using the neighbor-joining and maximum parsimony methods (21, 45). Resultant tree topologies were evaluated by bootstrap analyses (20) based on 1,000 resamplings.

Biotransformation of norfloxacin.

OM medium was used to monitor the decrease of norfloxacin and the production of metabolites. Cultures (40 ml) in 250-ml flasks were incubated at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Triplicate cultures and sterile controls were dosed at time zero with sterile norfloxacin at 30 μg ml−1. Samples (1 ml) of culture broth were taken at 7, 14, and 21 days. After centrifugation (13,000 × g) and filtration (0.45 μm), 10 μl of the filtered supernatant was injected directly for HPLC analysis.

Analysis by HPLC.

An 1100 series HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with a Kinetex C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) was used for detection, identification, and quantitation of norfloxacin metabolites. The mobile phase was composed of a 24-min linear gradient of 5 to 95% methanol in water, followed by a hold at 100% methanol for 3 min, with constant 0.1% formic acid delivered at 0.5 ml min−1. The diode array detector signal was monitored at 240 and 280 nm, with a reference wavelength of 360 nm.

The amount of norfloxacin in cultures was assessed by comparing the integrated area of the norfloxacin peak at 280 nm with that for the sterile controls. The amounts of metabolites were estimated by comparing the integrated area of each metabolite peak in the HPLC chromatogram at 240 or 280 nm to the integrated area of the norfloxacin peak for the sterile controls at the same wavelength. All amounts are expressed as percentages of the peak area of norfloxacin for the sterile controls.

Effects of reducing agents and free radical scavengers.

Norfloxacin (30 mg liter−1) was added to cultures in OM medium at time zero. GSH, DTT, and NADH (1.0 mM) were added after 7 days. In another experiment, ascorbic acid (0.05, 0.2, 0.5, or 1.0 mM) was added after 6 days. After incubation for 14 and 21 days, cultures and controls were analyzed by HPLC.

The free radical scavengers mannitol, sodium formate, and thiourea (24, 39) were introduced at 50 mM each to OM medium at time zero (with ascorbic acid added at 6 days) and to OM medium with only NaNO3 (1.0 g liter−1) as a nitrogen source. Cultures and controls were analyzed by HPLC at 14 days.

LC-MS.

A Finnigan TSQ Quantum Ultra mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for LC-ESI-MS and LC-ESI-MS/MS analyses (1). A photodiode array detector was used in line between the HPLC column and the electrospray interface. Chemical structures of metabolites were suggested by comparing the full-scan and product-ion mass spectra and UV absorption spectra with those in the literature.

NMR analyses.

Norfloxacin metabolites were analyzed by stopped-flow LC-NMR spectroscopy to confirm the chemical structures suggested by LC-ESI-MS/MS analyses. The isolated compounds were injected directly onto a 1200 series HPLC (Agilent Technologies) with a Zorbax Eclipse XDB C18 column (50 mm × 4.6 mm; Agilent Technologies). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% deuterated formic acid in deuterated water (D2O) (solution A) and 0.1% deuterated formic acid in deuterated methanol (MeOD) (solution B). A constant flow rate of 0.50 ml min−1 was maintained, and the metabolites were eluted using a linear gradient of 5 to 95% solution B over 10 min. The 95% solution B composition was held constant for 1 min, followed by a return to 95% solution A at 11.1 min. The diode array detector signal was monitored at 240 and 280 nm. Flow was stopped and the sample was collected in 30-μl NMR capillary tubes once the maximum absorbance was >60 absorbance units (AU). NMR spectra for each sample were acquired on a Bruker Avance NMR spectrometer operating at 600.133 MHz for proton NMR and equipped with a cryoprobe modified for flow applications with LC-NMR. A Bruker proton pulse sequence was employed that allowed for double solvent suppression at 3.15 and 4.70 ppm for analysis. For each compound, 1,024 scans were collected into 32,768 points over a spectrum width of 12,019.23 Hz. A recycle delay of 2.4 s was employed with a proton pulse width of 8.0 μs at a power level of −7.41 dΒ, and the total acquisition time was 1.36 s.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2 was submitted to the GenBank database under accession number HQ833039.

RESULTS

Isolation and identification of bacteria.

After four successive enrichment cultures, five strains of bacteria were isolated from wastewater cultures with N-phenylpiperazine as a nitrogen source, and seven strains were isolated from cultures with N-phenylpiperazine as a carbon source. Eleven of the strains were insensitive to norfloxacin at 30 mg liter−1, and one was sensitive. One of the norfloxacin-insensitive strains, from a culture with N-phenylpiperazine as a carbon source, appeared to degrade the added norfloxacin, with production of possible norfloxacin metabolites. This yellow pigment-producing microorganism, strain 4N2-2, was selected for further studies.

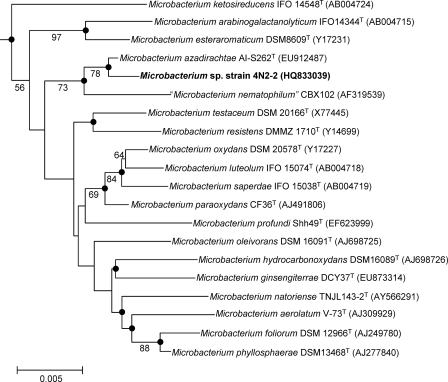

Strain 4N2-2 was shown by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis to be in the genus Microbacterium (49). The morphology of strain 4N2-2 was similar to descriptions of the genus Microbacterium (Gram-positive, aerobic, non-spore-forming rods, with yellow-pigmented colonies) (8, 35). A neighbor-joining tree was constructed with strain 4N2-2 and species closely related to the isolated strain within the genus Microbacterium (Fig. 1). The closest strains were Microbacterium azadirachtae strain AI-S262T (99.70% similarity), a plant growth promoter from neem seedlings (35), and “M. nematophilum” strain CBX102 (99.02% similarity), a pathogen for nematodes (25).

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2 based on 16S rRNA gene sequences constructed by the neighbor-joining method. Microbacterium barkeri DSM20145T (GenBank accession no. X77446) was used as the outgroup (not shown). Percentages at the nodes are the levels of bootstrap support (>50%) from 1,000 resampled data sets. The solid circles indicate that the corresponding nodes (groupings) were also recovered in the maximum parsimony tree, and the bar represents 0.005 nucleotide substitution per position.

HPLC, LC-ESI-MS/MS, and NMR analyses.

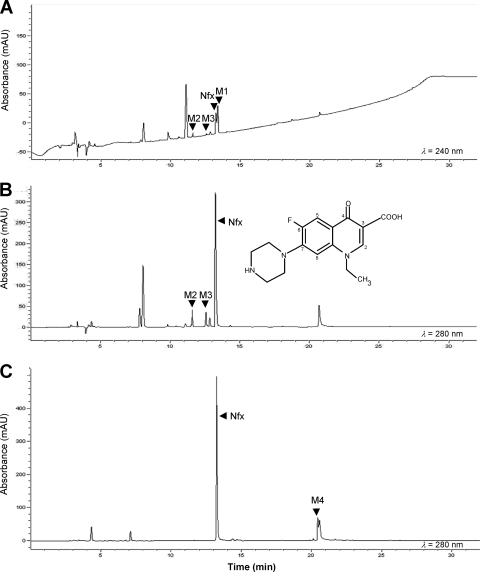

Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2 did not grow on norfloxacin as a sole carbon source, but it produced four possible metabolites from norfloxacin that were detected by HPLC (Fig. 2). The other peaks also appeared in the chromatograms of cultures without norfloxacin (data not shown). Peaks M1 (13.4 min) and M2 (11.6 min) were detected only in OM medium, M4 (20.4 min) was found only in 2.0 CM medium, and M3 (12.6 min) was detected in both media (Fig. 2). The major metabolite, M1, was detected in HPLC chromatograms only at 240 nm, whereas norfloxacin and the other three metabolites were detected at both 240 and 280 nm (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

HPLC elution profiles showing norfloxacin (Nfx) and metabolites produced in 14-day cultures of Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2. Cultures were grown in either OM medium with ascorbic acid (A and B) or 2.0 CM medium (C).

Metabolites were analyzed by HPLC with diode array spectrophotometry, by tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS) (Table 1), and by proton NMR (Table 2) to determine their structures. Protonated molecules ([M + H]+) were selected for analysis by MS/MS (Table 1). Losses of 18 and 44 Da from norfloxacin (m/z 320) implied losses of H2O and CO2 from the carboxyl group (m/z 302 and 276, respectively), losses of 43 and 57 Da from the 276-Da fragment (m/z 233 and 219, respectively) indicated losses of C2H5N and C3H7N from the piperazine ring, and a loss of 20 Da from the 276-Da fragment (m/z 256) implied a loss of HF. Table 2 reports the chemical shifts and coupling constants for the aromatic protons at C-2, C-5, and C-8 (Fig. 2) obtained by NMR analysis. The proton at C-2 showed little variation in chemical shift, indicating that there were no substitutions at the C-2 position or within the nitrogen-containing ring of the quinolone moiety. For norfloxacin, the protons at C-5 and C-8 appeared as doublets due to interaction with fluorine at C-6. Proton-fluorine coupling is strong, with larger coupling constants indicating short-range interactions.

Table 1.

Significant ions from full-scan and product-ion mass spectra and UV absorption maxima of norfloxacin and the metabolites produced by Microbacterium sp. 4N2-2

| Peaka | Compound | Production medium | UV λmax (nm) | Parent ion [M + H]+ (m/z) | Product-ion spectrum (m/z) (% relative abundance)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nfx | Norfloxacin | None | 278, 317 | 320 | 320 (64), 302 (39), 276 (100), 256 (33), 233 (50), 219 (12), 205 (6) |

| M1 | 8-Hydroxynorfloxacin | OM | 240, 329 | 336 | 336 (100), 318 (27), 293 (4), 292 (84), 275 (4), 272 (6), 263 (51), 249 (50), 234 (5), 223 (11), 221 (27), 220 (37), 207 (5), 206 (7), 205 (8) |

| M2 | 6-Defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin | OM | 278, 347 | 318 | 318 (36), 300 (12), 274 (100), 231 (52), 217 (10), 205 (10), 188 (8) |

| M3 | Desethylene norfloxacin | OM | 278, 340 | 294 | 294 (100), 277 (18), 276 (88), 274 (15), 256 (25), 251 (22), 233 (53), 205 (7), 203 (7) |

| M4 | N-Acetylnorfloxacin | 2.0 CM | 282 | 362 | 344 (49), 326 (45), 274 (87), 249 (25), 243 (39), 231 (100), 215 (29), 203 (24), 161 (8), 112 (23) |

As shown in Fig. 2.

Mass spectra were obtained by LC-MS/MS with a collision energy of 20 eV, except for peak M4 (35 eV).

Table 2.

1H-NMR chemical shifts and coupling constantsa of the aromatic protons of norfloxacin and the metabolites produced by Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2

| Compound (peak) | H assignment | Chemical shift (ppm) | Coupling constant (Hz) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norfloxacin | H-2 | 8.81 | ||

| H-5 | 7.95 | 12.67 | ||

| H-8 | 7.16 | 6.84 | ||

| 8-Hydroxynorfloxacin (M1) | H-2 | 8.72 | ||

| H-5 | 7.57 | 11.65 | ||

| 6-Defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin | H-2 | 8.74 | ||

| (M2) | H-5 | 7.63 | ||

| H-8 | 7.16 | |||

| Desethylene norfloxacin (M3) | H-2 | 8.72 | ||

| H-5 | 7.82 | 11.76 | ||

| H-8 | 6.78 | 7.03 |

Obtained by LC-NMR at 600 MHz.

The parent ion of M1 (m/z 336) had a mass that was 16 Da higher than that of norfloxacin. The product-ion spectrum (Table 1) showed neutral losses from the carboxyl group (m/z 318 and 292), fluorine (m/z 272), and piperazine (m/z 249), indicating addition of oxygen to the quinolone moiety of norfloxacin at the C-2, C-5, or C-8 position. The UV spectrum was similar to those of 8-hydroxyenrofloxacin and 8-hydroxyciprofloxacin (51, 53). The NMR spectrum of M1 (Table 2) showed two proton chemical shifts in the aromatic region. The peak at 8.72 ppm was assigned to the proton at C-2. The second peak, at 7.57 ppm, was a doublet with a coupling constant of 11.65 Hz. The coupling constant for the proton at 7.57 ppm indicates strong coupling to the fluorine atom at C-6. Based upon the chemical shifts and the coupling constants, the NMR spectrum is consistent with a hydroxyl substitution at the C-8 position, confirming the metabolite as 8-hydroxynorfloxacin.

The parent ion of M2 (m/z 318) had a mass that was 2 Da less than that of norfloxacin, suggesting the replacement of fluorine by a hydroxyl group. The product-ion spectrum (Table 1) showed fragment ions for neutral losses from the carboxyl group (m/z 300 and 274) and the piperazine ring (m/z 231 and 217), but it lacked the HF loss from the ion at m/z 274, indicating that fluorine was missing. The UV spectrum was similar to those of 6-defluoro-6-hydroxyenrofloxacin and 6-defluoro-6-hydroxyciprofloxacin (51, 53). The NMR peaks for the protons at C-5 and C-8 in the spectrum of M2 (Table 2) both appeared as singlets, consistent with defluorination followed by hydroxylation at C-6, confirming the metabolite as 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin.

The parent ion of M3 (m/z 294) had a mass that was 26 Da lower than that of norfloxacin, implying loss of an ethylene group from the piperazine ring. The product-ion spectrum (Table 1) showed a neutral loss of H2O from the carboxyl group (m/z 276), a subsequent HF loss indicating the presence of fluorine (m/z 256), and losses of C2H5N (m/z 233) and NH3 (m/z 277) from the remainder of the piperazine ring. Loss of NH3 is evidence of piperazine desethylation. The UV spectrum was similar to those of desethylated metabolites of enrofloxacin and ciprofloxacin (51, 53). In the NMR spectrum for M3 (Table 2), the chemical shift of H-8 was shifted upfield relative to that for the norfloxacin parent and M2. The upfield shift was consistent with protonation of the nitrogen atoms of the piperazine ring upon ring opening. The upfield chemical shift was also consistent with the predicted chemical shifts for M3 (ACD/HNMR Predictor, version 12.0; Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc., Toronto, Canada), confirming the metabolite as desethylene norfloxacin.

The parent ion of M4 (m/z 362) had a mass that was 42 Da higher than that of norfloxacin. Its product-ion pattern (Table 1) was similar, with major neutral losses that were almost identical, to that of N-acetylated norfloxacin with the substitution located at the N terminus of the piperazine ring (1). These data were consistent with identification of M4 as N-acetylnorfloxacin.

Production of metabolites under phosphate-limited conditions.

The amount of phosphate in OM medium was varied from 48 to 480 μM in 14-day cultures in an attempt to optimize metabolite production. Because the production of 8-hydroxynorfloxacin, 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin, and desethylene norfloxacin was >2-fold greater at a phosphate concentration of 96 μM than at 240 μM or higher (data not shown), a 96 μM concentration was selected for use in the OM medium used to produce metabolites for further analysis.

Effect of ascorbic acid.

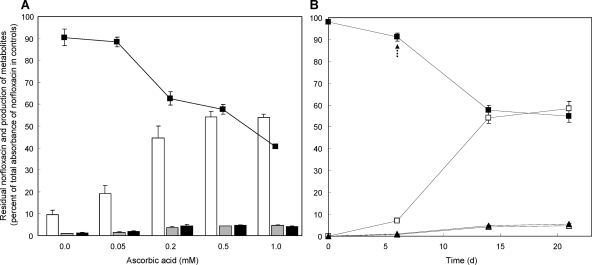

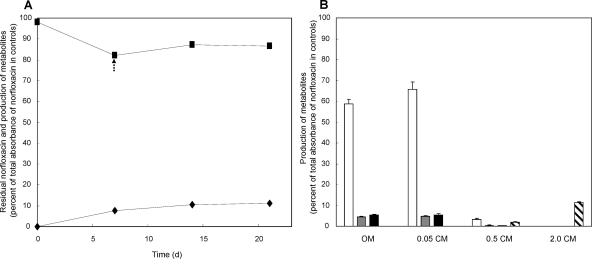

When various reducing agents (1.0 mM GSH, DTT, NADH, and ascorbic acid) were added to cultures of Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2 and incubated for 7 more days, only ascorbic acid affected metabolite production. The decrease of norfloxacin and production of 8-hydroxynorfloxacin (M1) and 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin (M2) were enhanced by 0.05 to 1.0 mM ascorbic acid (Fig. 3 A). Abiotic modification of norfloxacin in the presence of 0.5 mM ascorbate also produced 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin and desethylene norfloxacin (M3); the amounts were ca. 10% and 40%, respectively, of those produced by the bacterium (data not shown). The abiotic production of metabolites was slightly higher with 1.0 mM than with 0.5 mM ascorbic acid, so 0.5 mM ascorbic acid was selected to minimize abiotic production. After addition of 0.5 mM ascorbic acid, the decrease of norfloxacin and production of 8-hydroxynorfloxacin, 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin, and desethylene norfloxacin were enhanced (Fig. 3B). In 14 days, the norfloxacin level decreased by more than 40% compared to the control level (measured by the A280 value), and the level of the major metabolite, 8-hydroxynorfloxacin, increased to more than 50% of the control level (A240 value) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Degradation of norfloxacin and production of metabolites by Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2 after addition of ascorbic acid to OM medium. (A) Disappearance of norfloxacin (▪; 280 nm) and production of 8-hydroxynorfloxacin (white bars; 240 nm), 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin (gray bars; 280 nm), and desethylene norfloxacin (black bars; 280 nm) were measured in 14-day cultures, with ascorbic acid added at 6 days. (B) Disappearance of norfloxacin (▪; 280 nm) and production of 8-hydroxynorfloxacin (□; 240 nm), 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin (▴; 280 nm), and desethylene norfloxacin (▵; 280 nm) were monitored over time in the presence of 0.5 mM ascorbic acid (arrow) added at 6 days.

Effect of nitrate.

Single nitrogen sources (NH4+, NO3−, and NO2−) were used in OM medium at 1.0 g liter−1 for culture of Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2. NH4+ and NO2− at this concentration did not enhance the production of hydroxylated metabolites, but NO3− enhanced it even without ascorbic acid. The production of 8-hydroxynorfloxacin and 6-defluoro-6-dehydroxynorfloxacin in 14-day cultures in OM medium with 1.0 g liter−1 NaNO3 was 78% and 56%, respectively, of the production in regular OM medium with 0.5 mM ascorbic acid (data not shown). Growth of cultures was not significantly altered by the use of NH4+ or NO3−, but NO2− inhibited growth.

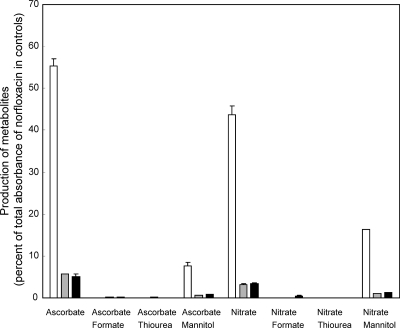

Inhibition of hydroxylated metabolite production by free radical scavengers.

Mannitol, sodium formate, and thiourea were added to cultures of Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2 in OM medium with either ascorbic acid or NO3− (no ascorbic acid). Production of the hydroxylated metabolites was almost abolished by formate and thiourea, but mannitol allowed production of ca. 13% and 38% of the hydroxylated metabolites in media with ascorbic acid and NO3−, respectively (Fig. 4). This result suggests that hydroxylation of norfloxacin may be mediated by free radicals in cultures with ascorbic acid or NO3−.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of production of hydroxylated norfloxacin metabolites by free radical scavengers. Production of 8-hydroxynorfloxacin (white bars; 240 nm), 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin (gray bars; 280 nm), and desethylene norfloxacin (black bars; 280 nm) was measured in 14-day cultures with various free radical scavengers. Sodium formate, thiourea, and mannitol (50 mM) were introduced to cultures in OM medium with ascorbic acid or NaNO3.

Effect of amino acids on metabolite production.

In cultures of Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2 in 2.0 CM medium (medium supplemented with 2.0 g liter−1 Casamino Acids), 8-hydroxynorfloxacin, 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin, and desethylene norfloxacin were not observed, but N-acetylnorfloxacin (M4) was produced (Fig. 2). In 14 days, ca. 10% of the norfloxacin disappeared and N-acetylnorfloxacin (at ca. 10% of the control level [A280 value]) was produced (Fig. 5 A). 8-Hydroxynorfloxacin, 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin, and desethylene norfloxacin were found in OM medium with low NH4+ and NO3− concentrations and in 0.05 CM medium (medium supplemented with 0.05 g liter−1 Casamino Acids), but they were not detected in 2.0 CM medium, even after addition of ascorbic acid. N-Acetylnorfloxacin was detected only in 2.0 CM medium (Fig. 5B). Production of 8-hydroxynorfloxacin, 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin, and desethylene norfloxacin was reduced about 90% in 0.5 CM medium and was totally abolished in 2.0 CM medium (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Production of metabolites of norfloxacin by Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2. (A) Decreases of norfloxacin (▪; 280 nm) and production of N-acetylnorfloxacin (⧫; 280 nm) in 2.0 CM medium were monitored by HPLC over time. The arrow at 7 days indicates the addition of ascorbic acid. (B) The amounts of 8-hydroxynorfloxacin (white bars; 240 nm), 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin (gray bars; 280 nm), desethylene norfloxacin (black bars; 280 nm), and N-acetylnorfloxacin (striped bars; 280 nm) were measured in 14-day cultures of OM medium and minimal medium supplemented with 0.05, 0.5, and 2.0 g liter−1 Casamino Acids (0.05 CM medium, 0.5 CM medium, and 2.0 CM medium, respectively).

Comparison of norfloxacin metabolism by Microbacterium sp. strains.

OM medium with 0.5 mM ascorbic acid and 2.0 CM medium were used to compare Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2 and M. nematophilum strain CBX102, kindly provided by C. Darby. After 21 days in OM medium with ascorbic acid, 4% 8-hydroxynorfloxacin, 0.5% 6-defluoro-6-hydroxynorfloxacin, and 0.8% desethylene norfloxacin were detected in cultures of M. nematophilum strain CBX102. The amounts of these three metabolites produced by M. nematophilum strain CBX102 were less than 10% of those produced by Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2; the amount of N-acetylnorfloxacin produced in 2.0 CM medium was about 20% of that produced by Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2.

DISCUSSION

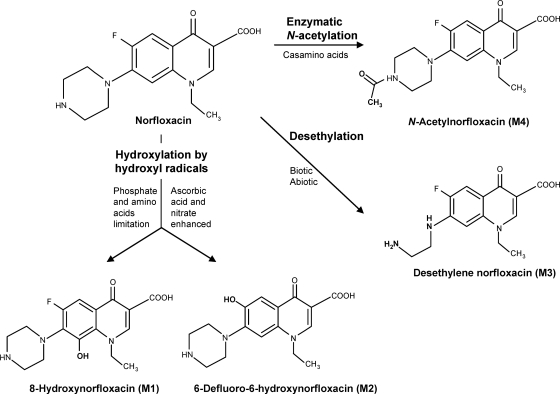

Norfloxacin metabolism by Microbacterium sp. 4N2-2, with proposed mechanisms and conditions for metabolite production, is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Proposed scheme for norfloxacin metabolism in cultures of Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2.

Microbacterium species, which are involved in diverse biodegradation reactions and in oxidation and reduction reactions, have been found in various environmental habitats (9, 29, 35, 44). Strains of Microbacterium spp. have been isolated from sugar beet factory wastewater (36), dye wastewater (14, 18), and activated sludge (12). After screening strains representing 18 different Microbacterium spp. from human clinical specimens, Gneiding et al. (22) reported that 22% were resistant to ciprofloxacin and another 22% were intermediate in resistance. They did not investigate the mechanism of fluoroquinolone resistance.

This is the first report of fluoroquinolone hydroxylation (at C-6 and C-8) and defluorination (at C-6) by an isolated bacterial strain. 8-Hydroxyfluoroquinolones are produced from enrofloxacin and ciprofloxacin by brown rot fungi (51, 53). In contrast, the nonoxidative 8-defluorination of sparfloxacin and lomefloxacin, which have two F atoms each, is photochemical (17, 19). 6-Defluoro-6-hydroxy and desethylene fluoroquinolones may be produced abiotically by photochemical reactions (10, 19, 46) as well as by fungal biodegradation (40, 51–53). The labile piperazine rings of fluoroquinolones can be desethylated by both abiotic and biotic processes (10, 46, 51). Desethylene norfloxacin has also been detected after administration of norfloxacin to chickens and pigs (3, 4).

N-Acetylation of norfloxacin by Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2 was favored in the presence of amino acids. N-Acetylnorfloxacin is also produced by some fungi (41) and bacteria, perhaps by an aminoglycoside N-acetyltransferase (1, 28, 43). Cell-free protein extracts from Microbacterium sp. 4N2-2 catalyzed in vitro N-acetylation of norfloxacin (data not shown).

Hydroxylation at C-6 and C-8, considering the enhancement by ascorbic acid and NO3− and the regulation by limited phosphate and amino acids, might be due to extracellular hydroxyl radicals, as in the brown rot fungus Gloeophyllum striatum (52). Abiotic production of several metabolites from ciprofloxacin, including 6-defluoro-6-hydroxyciprofloxacin and 8-hydroxyciprofloxacin, was achieved by hydroxyl radicals produced by an anodic Fenton system (54). Inhibition of hydroxylated metabolite production in Microbacterium sp. 4N2-2 by free radical scavengers indicated that production of these metabolites may be caused by reactive oxygen species, such as hydroxyl radicals (26). Ascorbic acid usually acts as an antioxidant, but it can stimulate hydroxyl radical formation in the presence of FeCl3 (6) and can act as a critical factor in enzymatic hydroxylation (39). NO3− reduction is involved in biodegradation of quinoline through hydroxylation in activated sludge (34), and NO3− is a source of hydroxyl radicals in photodecomposition reactions in surface water (32). Bacterial production of reactive oxygen species is closely related to the stringent response initiated by amino acid or phosphate depletion (37). Furthermore, some fluoroquinolones stimulate production of reactive oxygen species (6, 7), and some Microbacterium spp. are highly resistant to oxygen radicals because they produce galactoglycerolipids (38).

Expeditious degradation of antibacterial agents in the environment may prevent transfer of resistance genes and the appearance of new strains of pathogenic bacteria (1). In many fluoroquinolones, a fluorine at the 6 position is important for antibacterial potency, the 8 position is critical for antianaerobe activity, and the piperazine ring is important for potency against Gram-negative bacteria (5). The hydroxylation, N-acetylation, and desethylation of fluoroquinolones reduce antibacterial activity (43, 51). Thus, norfloxacin metabolites of Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2 should be less able to select for resistance in fluoroquinolone-sensitive bacterial strains.

Our results show that Microbacterium sp. strain 4N2-2 produces four metabolites from norfloxacin, through hydroxylation, oxidative defluorination, desethylation, and N-acetylation. These metabolites, of course, may be subjected to further degradation by other environmental microorganisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank C. E. Cerniglia for research support and helpful comments on the manuscript, as well as M. S. Bryant, S.-J. Kim, and D. L. Mendrick for useful suggestions. We also thank C. Darby for kindly providing a culture of Microbacterium nematophilum CBX102.

This research was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program (D.-W.K. and B.-S.K.) at the National Center for Toxicological Research, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The views presented in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adjei M. D., et al. 2006. Transformation of the antibacterial agent norfloxacin by environmental mycobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5790–5793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altschul S. F., et al. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anadón A., et al. 1995. Pharmacokinetics and tissue residues of norfloxacin and its N-desethyl- and oxo-metabolites in healthy pigs. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 18:220–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anadón A., Martínez-Larrañaga M. R., Vélez C., Díaz M. J., Bringas P. 1992. Pharmacokinetics of norfloxacin and its N-desethyl- and oxo-metabolites in broiler chickens. Am. J. Vet. Res. 53:2084–2089 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andersson M. I., MacGowan A. P. 2003. Development of the quinolones. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51(Suppl. S1):1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arriaga-Alba M., et al. 2008. Antimutagenic effects of vitamin C against oxidative changes induced by quinolones. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 46:38–43 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Becerra M. C., Albesa I. 2002. Oxidative stress induced by ciprofloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 297:1003–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Behrendt U., Ulrich A., Schumann P. 2001. Description of Microbacterium foliorum sp. nov. and Microbacterium phyllosphaerae sp. nov., isolated from the phyllosphere of grasses and the surface litter after mulching the sward, and reclassification of Aureobacterium resistens (Funke et al. 1998) as Microbacterium resistens comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1267–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cáceres T. P., Megharaj M., Malik S., Beer M., Naidu R. 2009. Hydrolysis of fenamiphos and its toxic oxidation products by Microbacterium sp. in pure culture and groundwater. Bioresour. Technol. 100:2732–2736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cardoza L. A., Williams T. D., Drake B., Larive C. K. 2003. LC/MS/MS and LC/NMR for the structure elucidation of ciprofloxacin transformation products in pond water solution. ACS Symp. Ser. Am. Chem. Soc. 850:146–160 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang X., et al. 2010. Determination of antibiotics in sewage from hospitals, nursery and slaughter house, wastewater treatment plant and source water in Chongqing region of Three Gorge Reservoir in China. Environ. Pollut. 158:1444–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen J.-A., et al. 2007. Degradation of environmental endocrine disruptor di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate by a newly discovered bacterium, Microbacterium sp. strain CQ0110Y. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 74:676–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen Y., et al. 1997. Microbial models of soil metabolism: biotransformations of danofloxacin. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 19:378–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Choi K., et al. 2004. Polyvinyl alcohol degradation by Microbacterium barkeri KCCM 10507 and Paenibacillus amylolyticus KCCM 10508 in dyeing wastewater. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 14:1009–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chun J., et al. 2007. EzTaxon: a web-based tool for the identification of prokaryotes based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57:2259–2261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duong H. A., et al. 2008. Occurrence, fate and antibiotic resistance of fluoroquinolone antibacterials in hospital wastewaters in Hanoi, Vietnam. Chemosphere 72:968–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Engler M., Rüsing G., Sörgel F., Holzgrabe U. 1998. Defluorinated sparfloxacin as a new photoproduct identified by liquid chromatography coupled with UV detection and tandem mass spectrometry. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1151–1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fan L., Ni J., Wu Y., Zhang Y. 2009. Treatment of bromoamine acid wastewater using combined process of micro-electrolysis and biological aerobic filter. J. Haz. Mat. 162:1204–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fasani E., Barberis Negra F. F., Mella M., Monti S., Albini A. 1999. Photoinduced C-F bond cleavage in some fluorinated 7-amino-4-quinolone-3-carboxylic acids. J. Org. Chem. 64:5388–5395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Felsenstein J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fitch W. M. 1971. Toward defining the course of evolution: minimum change for a specific tree topology. Syst. Zool. 20:406–416 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gneiding K., Frodl R., Funke G. 2008. Identities of Microbacterium spp. encountered in human clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3646–3652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Golet E. M., Alder A. C., Hartmann A., Ternes T. A., Giger W. 2001. Trace determination of fluoroquinolone antibacterial agents in urban wastewater by solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. Anal. Chem. 73:3632–3638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Halliwell B. 1977. Generation of hydrogen peroxide, superoxide and hydroxyl radicals during the oxidation of dihydroxyfumaric acid by peroxidase. Biochem. J. 163:441–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hodgkin J., Kuwabara P. E., Corneliussen B. 2000. A novel bacterial pathogen, Microbacterium nematophilum, induces morphological change in the nematode C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 10:1615–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huycke M. M., Moore D. R. 2002. In vivo production of hydroxyl radical by Enterococcus faecalis colonizing the intestinal tract using aromatic hydroxylation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 33:818–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jeon Y.-S., et al. 2005. jPHYDIT: a JAVA-based integrated environment for molecular phylogeny of rRNA sequences. Bioinformatics 21:3171–3173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jung C. M., Heinze T. M., Strakosha R., Elkins C. A., Sutherland J. B. 2009. Acetylation of fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agents by an Escherichia coli strain isolated from a municipal wastewater treatment plant. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106:564–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaneda Y., Ohnishi K., Yagi T. 2002. Purification, molecular cloning, and characterization of pyridoxine 4-oxidase from Microbacterium luteolum. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66:1022–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim S., Aga D. S. 2007. Potential ecological and human health impacts of antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant bacteria from wastewater treatment plants. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 10:559–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krause D. O., Dalrymple B. P., Smith W. J., Mackie R. I., McSweeney C. S. 1999. 16S rDNA sequencing of Ruminococcus albus and Ruminococcus flavefaciens: design of a signature probe and its application in adult sheep. Microbiology 145:1797–1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lam M. W., Tantuco K., Mabury S. A. 2003. PhotoFate: a new approach in accounting for the contribution of indirect photolysis of pesticides and pharmaceuticals in surface waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37:899–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee H.-B., Peart T. E., Svoboda M. L. 2007. Determination of ofloxacin, norfloxacin, and ciprofloxacin in sewage by selective solid-phase extraction, liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection, and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 1139:45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li Y., et al. 2010. Nitrate-dependent biodegradation of quinoline, isoquinoline, and 2-methylquinoline by acclimated activated sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 173:151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Madhaiyan M., et al. 2010. Microbacterium azadirachtae sp. nov., a plant-growth-promoting actinobacterium isolated from the rhizoplane of neem seedlings. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60:1687–1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matsuyama H., Kawasaki K., Yumoto I., Shida O. 1999. Microbacterium kitamiense sp. nov., a new polysaccharide-producing bacterium isolated from the wastewater of a sugar-beet factory. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1353–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McDougald D., et al. 2002. Defences against oxidative stress during starvation in bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 81:3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nakata K. 2000. High resistance to oxygen radicals and heat is caused by a galactoglycerolipid in Microbacterium sp. M874. J. Biochem. 127:731–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Osman A. M., et al. 1996. Microperoxidase/H2O2-catalyzed aromatic hydroxylation proceeds by a cytochrome-P-450-type oxygen-transfer reaction mechanism. Eur. J. Biochem. 240:232–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Parshikov I. A., et al. 2000. Microbiological transformation of enrofloxacin by the fungus Mucor ramannianus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2664–2667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Parshikov I. A., et al. 2001. The fungus Pestalotiopsis guepini as a model for biotransformation of ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 56:474–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Parshikov I. A., et al. 2002. Formation of conjugates from ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin in cultures of Trichoderma viride. Mycologia 94:1–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Robicsek A., et al. 2006. Fluoroquinolone-modifying enzyme: a new adaptation of a common aminoglycoside acetyltransferase. Nat. Med. 12:83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Röger P., Lingens F. 1989. Degradation of quinoline-4-carboxylic acid by Microbacterium sp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 57:279–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Saitou N., Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Santoke H., Song W., Cooper W. J., Greaves J., Miller G. E. 2009. Free-radical-induced oxidative and reductive degradation of fluoroquinolone pharmaceuticals: kinetic studies and degradation mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. A 113:7846–7851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shao B., Chen D., Zhang J., Wu Y., Sun C. 2009. Determination of 76 pharmaceutical drugs by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry in slaughterhouse wastewater. J. Chromatogr. A 1216:8312–8318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sunderland J., Tobin C. M., Hedges A. J., MacGowan A. P., White L. O. 2001. Antimicrobial activity of fluoroquinolone photodegradation products determined by parallel-line bioassay and high performance liquid chromatography. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Takeuchi M., Hatano K. 1998. Union of the genera Microbacterium Orla-Jensen and Aureobacterium Collins et al. in a redefined genus Microbacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:739–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Watkinson A. J., Murby E. J., Costanzo S. D. 2007. Removal of antibiotics in conventional and advanced wastewater treatment: implications for environmental discharge and wastewater recycling. Water Res. 41:4164–4176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wetzstein H.-G., Schmeer N., Karl W. 1997. Degradation of the fluoroquinolone enrofloxacin by the brown rot fungus Gloeophyllum striatum: identification of metabolites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4272–4281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wetzstein H.-G., Schneider J., Karl W. 2006. Patterns of metabolites produced from the fluoroquinolone enrofloxacin by basidiomycetes indigenous to agricultural sites. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 71:90–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wetzstein H.-G., Stadler M., Tichy H.-V., Dalhoff A., Karl W. 1999. Degradation of ciprofloxacin by basidiomycetes and identification of metabolites generated by the brown rot fungus Gloeophyllum striatum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1556–1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Xiao X., Zeng X., Lemley A. T. 2010. Species-dependent degradation of ciprofloxacin in a membrane anodic Fenton system. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58:10169–10175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xu W., et al. 2007. Occurrence and elimination of antibiotics at four sewage treatment plants in the Pearl River Delta (PRD), South China. Water Res. 41:4526–4534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang Z., Schwartz S., Wagner L., Miller W. 2000. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J. Comput. Biol. 7:203–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]