Abstract

The molecular fingerprinting technique terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) was used in combination with sequence-based approaches to evaluate the geographic distribution of secondary metabolite biosynthetic genes in strains of the marine actinomycete Salinispora arenicola. This study targeted ketosynthase (KS) domains from type I polyketide synthase (PKS) genes and revealed four distinct clusters, the largest of which was comprised of strains from all six global locations sampled. The remaining strains fell into three smaller clusters comprised of strains derived entirely from the Red Sea, the Sea of Cortez, or around the Island of Guam. These results reveal variation in the secondary metabolite gene collectives maintained by strains that are largely clonal at the 16S rRNA level. The location specificities of the three smaller clusters provide evidence that collections of secondary metabolite genes in subpopulations of S. arenicola are endemic to these locations. Cloned KS sequences support the maintenance of distinct sets of biosynthetic genes in the strains associated with each cluster and include four that had not previously been detected in S. arenicola. Two of these new sequences were observed only in strains derived from Guam or the Sea of Cortez. Transcriptional analysis of one of the new KS sequences in conjunction with the production of the polyketide arenicolide A supports a link between this sequence and the associated biosynthetic pathway. From the perspective of natural product discovery, these results suggest that screening populations from distant locations can enhance the discovery of new natural products and provides further support for the use of molecular fingerprinting techniques, such as T-RFLP, to rapidly identify strains that possess distinct sets of biosynthetic genes.

INTRODUCTION

The genus Salinispora is an obligate marine actinomycete taxon comprised of the formally described species S. tropica and S. arenicola (17) and a third species for which the name “S. pacifica” has been proposed (12). The genus is broadly distributed in tropical and subtropical marine sediments, with S. arenicola displaying the widest geographical range (12). While the genus is clearly resolved based on 16S rRNA phylogeny, the three species share 99% 16S sequence identity and are better resolved using less-conserved phylogenetic markers (12). To date, no intraspecific diversity has been reported for S. tropica, and only a few nucleotide changes have been observed in S. arenicola, including two polymorphisms that are restricted to populations from the Sea of Cortez (12).

Bacteria that share closely related or identical 16S rRNA gene sequences can vary greatly at the genomic level (27). These genomic differences often are concentrated in islands, regions of the chromosome that are known to house genes associated with ecological adaptation (3). A comparative analysis of the genome sequences of S. tropica (strain CNB-440) and S. arenicola (strain CNS-205) revealed 21 major genomic islands, within which secondary metabolism represented the major class of functionally annotated genes (20). These results were used to suggest that secondary metabolism is linked to ecological adaptation within this group of bacteria, and that the acquisition of natural product biosynthetic genes represents a previously unrecognized force driving bacterial diversification (20).

Despite evidence that genes associated with secondary metabolism are transferred horizontally, a previous phenotypic analysis of S. arenicola strains derived from geographically distant locations revealed that all produced a common series of metabolites. These results provided evidence that the maintenance of the associated biosynthetic pathways were under strong selective pressures (13). This study also identified secondary metabolites that were observed sporadically among strains of S. arenicola and provided evidence that the production of these accessory compounds could be linked to the geographical source of the strains. Similarly, a study of type II polyketide synthase (PKS) sequences showed little overlap in the secondary metabolite genes observed in soils obtained from different geographic locations (26), leading to the conclusion that it is not common for these genes to be cosmopolitan. Despite the potential ecological importance and extensive commercial exploitation of bacterial secondary metabolites, little is known about the biogeographic distribution of the biosynthetic pathways responsible for the production of these compounds.

In the present study, both molecular and culture-based techniques were used to examine secondary metabolism among strains of S. arenicola. Polyketide synthase (PKS) genes were targeted, as they represent the major class of secondary metabolite biosynthetic genes in S. arenicola (20) and are responsible for the production of compounds of therapeutic interest, e.g., the antibiotic rifamycin. More specifically, ketosynthase (KS) domains, which are responsible for the condensation of activated carboxylic acid monomers onto a growing acyl chain during polyketide assembly (6), were targeted as they have proven to be phylogenetically informative in terms of making predictions about the products of the associated biosynthetic pathways (7).

The results presented here provide evidence that subpopulations of bacteria derived from specific locations can maintain distinct sets of biosynthetic genes. Like a prior study that employed T-RFLP to analyze community-level biosynthetic gene diversity (26), the present study provides additional evidence for biogeographic patterns associated with secondary metabolism, in this case, among strains of a single species. These results expand upon our understanding of species-specific secondary metabolite production in the genus Salinispora and provide new evidence for the maintenance of location-specific sets of secondary metabolite genes in subpopulations of marine bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

S. arenicola strains.

The 30 S. arenicola strains used in this study were isolated from six broadly distributed collection sites (the Bahamas, Guam, Palau, the Red Sea, the Sea of Cortez, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) as previously described (12).

T-RFLP.

For terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP), each strain was inoculated from independent frozen stocks (three replicates per strain) into sterile 15-ml Falcon tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) containing 2 ml of medium A1 (1.0% starch, 0.2% peptone, 0.4% yeast extract, dissolved in 100% seawater). The cultures were incubated at 28°C with shaking at 220 rpm for 72 h prior to DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was prepared from each culture as previously described (11). KS domains were PCR amplified from genomic DNA using degenerate primers modified from Ginolhac and colleagues (8): the forward primer was KSf-Hex (5′-CCSCAGSAGCGCSTSTTSCTSGA-3′), labeled at the 5′ end with hexachlorofluorescein, and the reverse was KSr (5′-TSGAGGCSCACGGSACSGGSAC-3′). These primers target KS domains associated with type I PKS and hybrid PKS/nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) genes. Each 100-μl PCR mixture contained 100 pmol of each primer, 5 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 10× PCR buffer II (Applied Biosystems), 2.5 mM MgCl2 (Applied Biosystems), 7 μl dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ), 10 nmol deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and 2 μl of template DNA. The cycling program was performed using a Bio-Rad iCycler (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) with the following steps: 15 min at 95°C, followed by 1 cycle of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 65°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by 33 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 62°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by 10 min at 72°C. To increase the concentration of PCR products prior to restriction digestion, two replicate PCRs were pooled, ethanol precipitated with sodium acetate (20 μl, 3 M, pH 5.2), and resuspended in 12 μl of double-distilled H2O. The concentrated PCR products (ca. 20 ng of DNA) were digested for 2 h using the restriction enzyme HhaI (Promega, Madison, WI). Fluorescently labeled terminal restriction fragments (T-RFs) were separated and detected using a MegaBACE 1000 capillary sequencer (GE Healthcare, Sunnyvale, CA). T-RF sizes were determined by comparison to the MegaBACE ET550-R internal size standard. Before injection, 2 μl of the DNA sample was denatured in the presence of 7.96 μl Tween 20 solution (0.1%) and 0.04 μl MegaBACE ET550-R size standard at 95°C for 1 min. Injections were performed electrokinetically at 3 kV for 60 s, and electrophoresis was run at 5 kV for 179 min. The lengths of the fluorescent T-RFs were determined using GeneMarker software (SoftGenetics LLC, State College, PA).

Statistical analysis of T-RFLP profiles.

T-RFLP analyses were performed on three independent replicates for each strain. Only peaks with fluorescence intensities of greater than 50 U were counted. The results were recorded in a presence (+) or absence (−) matrix that was sorted according to T-RF size in base pairs. Replicate T-RFs with sizes of ±1.0 bp were assigned to the median or most common number of base pairs. T-RFs with strong fluorescence intensities (>500 U) were highly consistent among replicates, while lower intensity peaks sometimes were variable, in which case only those observed in at least two of three replicates for any one strain were analyzed. Correspondence analysis (CA) and principal component analysis (PCA) were performed on the data matrix using the multivariate analysis software ADE-4 (http://pbil.univ-lyon1.fr/ADE-4) as previously described (4). To evaluate the relationships among strains assigned to T-RFLP cluster I, CA and PCA also were performed on this subset of the data. Significant clustering patterns in the CA and PCA plots were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Cloning, sequencing, and phylogenetic analysis.

KS domains were cloned and sequenced from representative strains that showed distinct T-RFLP patterns as visually inferred from the CA analysis. Strain CNS-205, for which a genome sequence is available, was included as a positive control. The same PCR conditions and primers (KSf and KSr) used in the T-RFLP studies were applied without the hexachlorofluorescein label. The PCR products were gel purified using the Mini EluteGel extraction kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). To improve cloning efficiency, additional A overhangs were generated using AmpliTaq gold polymerase (Applied Biosystems), and approximately 100 ng of DNA was cloned into the pCR-2.1 TOPO vector and transformed into Escherichia coli TOP10 (TOPO-TA cloning kit; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

KS sequences were PCR amplified from randomly selected E. coli TOP10 clones using the KSf and KSr primers. Clones containing inserts of the expected size (ca. 650 bp) were grown overnight in LB medium according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). Plasmids were extracted using the QIAprep Miniprep kit (Qiagen) and inserts sequenced using the m13 forward primer on an ABI Prism capillary electrophoresis genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) by SeqXcel Inc. (La Jolla, CA). Nucleotides and translated amino acid sequences were compared to sequences deposited in GenBank using the BLASTN and BLASTP tools (1). BLAST results were analyzed to identify the closest match associated with an experimentally characterized biosynthetic pathway.

PCR probing for KS domains.

The distribution of specific KS sequences was evaluated using nondegenerate primers constructed with the Primernet and Beacon Designer v. 6.0 software (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA). These primers targeted conserved regions within each of the new KS sequence types identified in this study. In addition, a rifamycin-specific primer set targeting the second KS domain in the PKS gene Sare1250 (YP_001536146), as identified from the genome sequence of S. arenicola strain CNS-205, was used as a positive control. The PCR conditions, other than annealing temperatures, were the same as those previously described for the T-RFLP experiments. All PCR products were purified and sequence verified as previously described.

Transcription analysis of KS domains.

Strains were cultured in 1 liter of medium A1 with shaking at 220 rpm and 28°C for 14 days. After 3, 7, and 14 days of incubation, 1-ml samples were transferred to sterile, RNase-free Eppendorf tubes. Nucleic acids were extracted using the RiboPure bacteria kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions and incubated for 2 h at 37°C in 4 μl (2 U/μl) DNase 1 (Ambion) and 0.5 μl (40 U/μl) of the recombinant RNase inhibitor RNaseOUT (Invitrogen). After incubation, DNase 1 was inactivated according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Control PCRs were performed using 50 ng of DNase 1-treated RNA as the template and the 16S ribosomal DNA primers FC27 (5′ to 3′, AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG) and RC1492 (5′ to 3′, TACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT) as previously described (10) to verify that no genomic DNA (gDNA) was present prior to cDNA synthesis. The high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) with random primers was used to synthesize cDNA following the manufacturer's instructions and the quality of the newly synthesized cDNA examined by agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR using KS-specific primers and ca. 50 ng of cDNA was performed as described for the T-RFLP studies, and appropriately sized products were gel purified and sequence verified using the methods employed for the cloning studies.

Fermentation and secondary metabolite analysis.

Seed cultures (25 ml in 125-ml Erlenmeyer flasks) were grown in medium A1 and, for some strains, also in medium C1 (1% glucose, 3% soluble starch, 0.5% peptone, 1% soybean flour, 0.5% yeast, 0.2% CaCO3, dissolved in 100% seawater) for 2 to 4 days and then transferred to 2.8-liter Fernbach flasks containing 1 liter of the same medium. The flasks were shaken at 230 rpm (25 to 27°C), and 25-ml aliquots were removed on days 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11. Time point samples were extracted three times with 25 ml ethyl acetate, and the organic layers separated, combined, and concentrated to dryness in vacuo. The extracts were weighed and resuspended in 1:1 acetonitrile-methanol to yield a final concentration of 1 mg/ml.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) data were obtained at 254 nm by injecting 5 μl of each extract onto a Hewlett-Packard series 1100 LC-MS with a reversed-phase C18 column (4.6 mm by 100 mm; 5-μm particle size; Phenomenex) and a gradient of 10% acetonitrile–90% water to 100% acetonitrile run for more than 25 min. Mass spectra were collected (scanning 100 to 2,000 atomic mass units) in the positive ionization mode (electrospray ionization [ESI] voltage, 5.0 kV; capillary temperature, 200°C; auxiliary and sheath gas pressure 5 U and 70 lb/in2, respectively). All detectable peaks were evaluated by comparison of molecular weights, UV spectra, and retention times with published values and those maintained in an in-house database.

Accession numbers.

All sequences have been deposited in GenBank or the EMBL nucleotide sequence database and assigned the accession numbers GU561858 to GU561891 and FR669451 to FR669470, respectively.

RESULTS

T-RFLP analyses.

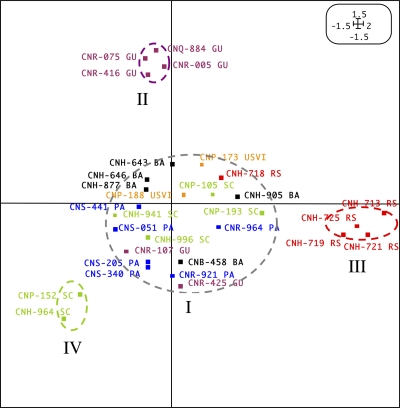

Ketosynthase (KS) domains from polyketide synthase (PKS) genes were PCR amplified from 30 S. arenicola strains derived from six global collection sites (Table 1). The products of triplicate independent PCR amplifications per strain were analyzed by T-RFLP and found to be highly reproducible, with (on average) 93% of the T-RFs being observed in all three replicates from each S. arenicola strain (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). An initial PCA, which included data for all strains, was not linearly distributed and showed obvious horseshoe formations (19). For this reason, the data were subjected to CA, which assumes a unimodal species response curve (15). An ordination diagram of the CA revealed four primary clusters (I to IV) (Fig. 1) that were significantly different along both ordination axes (P < 0.001, determined by analysis of variance [ANOVA]). The correspondence analysis Eigenvalues were 27 and 23% for the first and second ordination axes, respectively, suggesting that 50% of the observed variation in the data could be attributed to significant but unknown variables and not to random events. Cluster I is populated by the largest number of strains (20) and includes representatives from all six of the collection sites. The strains comprising cluster I were subjected to an independent PCA, and no evidence of subclustering was observed (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Clusters II to IV each are comprised of a subset of strains originating from three of the six locations, with four of six strains from Guam (CNR-075, CNQ-884, CNR-005, and CNR-416) forming cluster II, four of five strains from the Red Sea (CNH-713, CNH-719, CNH-721, and CNH-725) forming cluster III, and two of six strains from the Sea of Cortez (CNP-152 and CNH-964) forming cluster IV. In total, 10 of 30 strains fell into clusters II to IV, suggesting considerable biosynthetic diversity among strains that are largely clonal at the 16S level. An analysis of the T-RFs associated with the strains comprising clusters II to IV revealed three that were unique to each group (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), suggesting that these fragment lengths play a role in driving the observed clustering.

Table 1.

T-RFLP and KS sequencing results for Salinispora arenicola strainse

| Strain | Origin | T-RFLP cluster | Clone (no.) | No. of KS sequences | Accession no. | Top BLASTP matcha | % Amino acid identity | Source (gene) | Productb (pathway) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNB-458 | BA | I | No | ||||||

| CNH-643 | BA | I | Yes (17) | 3 | FR669454 | YP_001536144 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1248) | Rifamycin |

| 4 | FR669453 | YP_001536145 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1249) | Rifamycin | ||||

| 2 | FR669452 | YP_001537951 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare3152) | Unknown (pks5) | ||||

| 8 | FR669451 | ABF88750 | 60 | Sorangium cellulosum | Epothilone (new KS1) | ||||

| CNH-646 | BA | I | No | ||||||

| CNH-877 | BA | I | No | ||||||

| CNH-905 | BA | I | Yes (16) | 1 | FR669455 | YP_001536144 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1248) | Rifamycin |

| 1 | FR669456 | YP_001536145 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1249) | Rifamycin | ||||

| 2 | FR669457 | YP_001536890 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare2029) | Unknown (pks3a) | ||||

| 2 | FR669458 | YP_001539688 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare4951) | Unknown (pks1c) | ||||

| 5 | FR669459 | AAZ9438675 | 73 | Streptomyces platensis | Pladienolide (new KS2) | ||||

| CNR-107 | Guam | I | No | ||||||

| CNR-425 | Guam | I | No | ||||||

| CNQ-884 | Guam | II | Yes (11) | 2 | GU561858 | YP_001537951 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare3152) | Unknown (pks5) |

| 1 | GU561859 | YP_001537953 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare3154) | Unknown (pks5) | ||||

| 3 | GU561860 | YP_001539688 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare4951) | Unknown (pks1c) | ||||

| 4 | GU561861 | ABC875098 | 74 | Amycolatopsis orientalis | ECO-0501 (new KS3) | ||||

| 1 | GU561862 | AAZ94386 | 73 | Streptomyces platensis | Pladienolide (new KS2) | ||||

| CNR-075 | Guam | II | Yes (9) | 1 | GU561863 | YP_001537951 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare3152) | Unknown (pks5) |

| 2 | GU561864 | YP_001537953 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare3154) | Unknown (pks5) | ||||

| 1 | GU561865 | YP_001539688 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare4951) | Unknown (pks1c) | ||||

| 2 | GU561866 | ABC875098 | 74 | Amycolatopsis orientalis | ECO-0501 (new KS3) | ||||

| 3 | GU561867 | AAZ94386 | 73 | Streptomyces platensis | Pladienolide (new KS2) | ||||

| CNR-005 | Guam | II | No | ||||||

| CNR-416 | Guam | II | No | ||||||

| CNS-205c | Palau | I | Yes (32) | 5 | GU561868 | YP_001536143 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1247) | Rifamycin |

| 2 | GU561869 | YP_001536145 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1249) | Rifamycin | ||||

| 3 | GU561870 | YP_001536890 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare2029) | Unknown (pks3a) | ||||

| 1 | GU561871 | YP_001537255 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare2407) | Unknown (pksnrps2) | ||||

| 4 | GU561872 | YP_001537950 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare3151) | Unknown (pks5) | ||||

| 4 | GU561873 | YP_001537951 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare3152) | Unknown (pks5) | ||||

| 9 | GU561874 | YP_001537955 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare3156) | Unknown (pks5) | ||||

| 4 | GU561875 | YP_001539688 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare4951) | Unknown (pks1c) | ||||

| CNR-921 | Palau | I | No | ||||||

| CNR-964d | Palau | I | Yes (15) | 4 | FR669460 | YP_001536143 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1247) | Rifamycin |

| 2 | FR669461 | YP_001536145 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1249) | Rifamycin | ||||

| 2 | FR669462 | YP_001536890 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare2029) | Unknown (pks3a) | ||||

| 4 | FR669463 | YP_001537955 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare3156) | Unknown (pks5) | ||||

| 3 | FR669464 | YP_001539688 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare4951) | Unknown (pks1c) | ||||

| CNS-051 | Palau | I | No | ||||||

| CNS-340d | Palau | I | No | ||||||

| CNS-441d | Palau | I | No | ||||||

| CNH-718 | RS | I | No | ||||||

| CNH-713 | RS | III | No | ||||||

| CNH-719 | RS | III | No | ||||||

| CNH-721 | RS | III | Yes (21) | 1 | GU561876 | YP_001536929 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare2072) | Unknown (sid1) |

| 3 | GU561877 | YP_001537255 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare2407) | Unknown (pksnrps2) | ||||

| 2 | GU561878 | YP_001539688 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare4951) | Unknown (pks1c) | ||||

| 15 | GU561879 | ABF88750 | 69 | Sorangium cellulosum | Epothilone (new KS1) | ||||

| CNH-725 | RS | III | Yes (11) | 1 | GU561880 | YP_001536890 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare2029) | Unknown (pks3a) |

| 2 | GU561881 | YP_001537255 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare2407) | Unknown (pksnrps2) | ||||

| 1 | GU561882 | YP_001539688 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare4951) | Unknown (pks1c) | ||||

| 7 | GU561883 | ABF88750 | 69 | Sorangium cellulosum | Epothilone (new KS1) | ||||

| CNH-941 | SC | I | No | ||||||

| CNH-996 | SC | I | No | ||||||

| CNP-105 | SC | I | No | ||||||

| CNP-193 | SC | I | No | ||||||

| CNH-964 | SC | IV | Yes (24) | 1 | GU561884 | YP_001536145 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1249) | Rifamycin |

| 2 | FR669465 | YP_001536146 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1250) | Rifamycin | ||||

| 4 | FR669466 | YP_001537951 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare3152) | Unknown (pks5) | ||||

| 1 | GU561885 | YP_001539688 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare4951) | Unknown (pks1c) | ||||

| 8 | GU561886 | AAN85523 | 61 | Streptomyces atroolivaceus | Leinamycin (new KS4) | ||||

| 7 | FR669467 | ABF88750 | 69 | Sorangium cellulosum | Epothilone (new KS1) | ||||

| 1 | GU561887 | AAZ94386 | 73 | Streptomyces platensis | Pladienolide (new KS2) | ||||

| CNP-152 | SC | IV | Yes (24) | 4 | GU561888 | YP_001536145 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1249) | Rifamycin |

| 1 | FR669470 | YP_001536146 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare1250) | Rifamycin | ||||

| 3 | GU561889 | YP_001536890 | 100 | S. arenicola (Sare2029) | Unknown (pks3a) | ||||

| 4 | FR669469 | AAN85523 | 60 | Streptomyces atroolivaceus | Leinamycin (new KS4) | ||||

| 5 | GU561890 | AAN85523 | 61 | Streptomyces atroolivaceus | Leinamycin (new KS4) | ||||

| 3 | GU561891 | AAN85523 | 51 | Streptomyces atroolivaceus | Leinamycin (new KS4) | ||||

| 4 | FR669468 | ABF88750 | 69 | Sorangium cellulosum | Epothilone (new KS1) | ||||

| CNP-173 | USVI | I | No | ||||||

| CNP-188 | USVI | I | No |

Top matches to experimentally characterized PKS pathways.

Pathways new to S. arenicola are numbered; otherwise, names are from the CNS-205 genome sequence.

The genome sequence is available at http://genome.ornl.gov/microbial/sare/.

Strains not included in Jensen et al. (13).

Top BLASTP matches and the products of the pathways associated with those matches are shown. Sequences that share <80% amino acid identity to those previously observed in the genome sequence of S. arenicola (strain CNS-205) are in boldface. Products observed as part of a previous study (12) are italicized. BA, Bahamas; RS, Red Sea; SC, Sea of Cortez; USVI, U.S. Virgin Islands.

Fig. 1.

Correspondence analysis of T-RFLP data derived from PCR-amplified S. arenicola ketosynthase sequences. Clusters are circled and indicated with Roman numerals (I to IV). Sampling locations are abbreviated and color coded: GU, Guam, purple; PA, Palau, blue; SC, Sea of Cortez, green; USVI, U.S. Virgin Islands, orange; RS, Red Sea, red; BA, Bahamas, black. Values in the upper right corner indicate minimum and maximum abscissa and ordinate values. Eigenvalues were 27 and 23% for the first and second ordination axes, respectively.

Ketosynthase sequences.

To better understand the genetic basis for the T-RFLP results, KS domains were cloned and sequenced from 10 strains, consisting of 2 to 4 strains from each of the four T-RFLP clusters (Table 1). In total, 180 clones were sequenced, and all but 5 of these were identified as KS domains based on BLAST analyses. The cluster I strains include two from Palau (CNS-205 and CNR-964) and the Bahamas (CNH-905 and CNH-643) that are well separated in the ordination diagram (Fig. 1). The Palau strain CNR-964 yielded five distinct KS sequences out of 15 clones sequenced (Table 1). All five of these sequences shared 100% amino acid identity with sequences previously observed in the S. arenicola CNS-205 genome (20) and can be linked to the biosynthesis of rifamycin and three biosynthetic pathways (pks3A, pks5, and pks1C) for which the products have yet to be determined. The second cluster I strain from Palau (CNS-205) was used as a positive control, since a genome sequence is available. From this library, 8 distinct sequences were identified out of 32 clones analyzed. These sequences include the same five KS sequences observed in CNR-964 as well as sequences associated with the previously defined pathways pksnrps2 and pks5 (20). These sequences represent 8 of the 25 KS sequences in the CNS-205 genome that the PCR primers were designed to detect (9). Clone libraries from the two cluster I strains from the Bahamas (CNH-643 and CNH-905) each revealed sequences previously observed from S. arenicola as well as one new sequence. Among experimentally characterized biosynthetic genes, the new sequence from CNH-643 (new KS1) shares closest amino acid identity (60%) to a KS domain associated with epothilone biosynthesis in Sorangium cellulosum (14). The new sequence from CNH-905 (new KS2) shares 73% amino acid identity to a KS domain associated with the biosynthesis of the polyketide-derived secondary metabolite pladienolide (22).

The cluster II (Guam) strains selected for cloning and sequencing were CNQ-884 and CNR-075. These strains were in close proximity in the ordination diagram (Fig. 1), and the same five KS sequences were detected in both libraries. Three of these sequences were observed in the CNS-205 genome; one shared >99% identity with the new KS2 sequence observed in the cluster I strain CNH-905, while the remaining sequence (new KS3) represents a third KS that had not previously been observed in S. arenicola. This sequence shares 61% amino acid identity to a KS associated with the biosynthesis of the polyketide-derived macrolide ECO-0501 produced by Streptomyces aizunensis (18). This sequence was observed only in libraries generated from strains isolated from Guam.

The two cluster III (Red Sea) strains for which libraries were generated (CNH-721 and CNH-725) each revealed three KS sequences that were observed previously in the CNS-205 genome as well as one sequence that was nearly identical (>99% nucleotide identity) to the new KS1 sequence that also was detected in cluster I strain CNH-643. The cluster IV Sea of Cortez strains CNH-964 and CNP-152 generated clones that also included the identical new KS1 sequence, which in total was observed from three of the six locations sampled (the Bahamas, the Red Sea, and the Sea of Cortez). This sequence was observed in 5 of the 10 strains for which libraries were generated and in strains assigned to three of the four clusters (I, III, and IV) identified in Fig. 1. All five of the new KS1 sequences shared 100% amino acid identity, suggesting that they are associated with the production of similar metabolites. One of the Sea of Cortez strains also contained the new KS2 sequence type. In total, the new KS2 sequences were observed in 4 of the 10 strains from which libraries were generated and three of the four T-RFLP clusters (I, II, and IV). All of the new KS2 sequences were closely related to each other (>99% amino acid identity). Also detected in both cluster IV Sea of Cortez strains was a second location-specific KS sequence type (new KS4). These sequences share 51 to 61% amino acid identity with those involved in the biosynthesis of the polyketide-derived metabolite leinamycin (24). This is the first time these KS sequences were observed in any S. arenicola strains. Overall, libraries generated from 10 different strains revealed the presence of four KS sequence types that share little identity with any sequence previously observed in S. arenicola. These sequences are not closely related to any associated with an experimentally characterized biosynthetic pathway or deposited in a public database. The new KS3 and KS4 sequence types were detected only in strains from Guam and the Sea of Cortez, respectively, providing evidence for the localized distribution of some biosynthetic pathways.

PCR probing.

To further assess the distribution of the four new KS sequences (new KS1 to KS4) in S. arenicola, 25 strains from the six collection sites were probed using PCR primers targeting conserved regions specific to these sequence types (Table 2). In addition, primers targeting a KS domain associated with rifamycin biosynthesis were used as a positive control, since this compound has been observed consistently from S. arenicola (13). As expected, the four new KS sequences identified in the clone libraries also were detected in the same strains when specific PCR primers targeting these sequences were used (Table 3). The specific primers additionally detected the new KS1 sequence in three strains for which libraries had not been generated: strain CNB-458 (cluster I; Bahamas) and the two remaining cluster III strains from the Red Sea (CNH-713 and CNH-719). Likewise, the new KS2 sequence was detected in strain CNB-458 (cluster I; Bahamas) and the new KS3 sequence in a third cluster II strain (CNR-416) derived from Guam. The new KS4 sequence remained restricted to the two previously identified Sea of Cortez strains. These results provide further evidence that the distributions of the new KS3 and KS4 sequences are restricted to S. arenicola strains from Guam and the Sea of Cortez, respectively (Table 3). The KS sequence associated with rifamycin biosynthesis (Sare1247; YP_01157878) was detected in all 25 strains despite not being observed in 4 of the 10 libraries created using the degenerate primers. To test the efficacy of the T-RFLP and cloning experiments, which employed the same degenerate PCR primers, we examined the T-RFLP results from all 30 strains and observed a 111-bp T-RF (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) predicted to be associated with the rifamycin biosynthetic pathway based on the location of the first HhaI restriction site (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) in the second KS domain of gene Sare1250 (YP_001536146). Although the limitations of T-RFLP have been well documented (5), the consistent presence of this T-RF suggests that the T-RFLP experiments did not suffer from the same detection limitations as the cloning experiments.

Table 2.

PCR primers used to target specific KS domain sequences

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Target KS domain | Annealing temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| KS1_f | CCCCAGCAGCGCGTGTTGCTGGA | New KS1 | 74 |

| KS1_r | GTCCCGGTGCCGTGGGCCTCGA | ||

| KS2_f | CCCCAGGAGCGCGTGTTCCTGGA | New KS2 | 71 |

| KS2_r | GTGCCGGTGCCGTGGGCCTCCA | ||

| KS3_f | CCCCAGCAACGGCTGCTGCTGGA | New KS3 | 72 |

| KS3_r | GTGCCGGTGCCGTGGGCCTCCA | ||

| KS4_f | CCCCAGCAGCGCCTGTTCCTGGA | New KS4 | 70 |

| KS4_r | GTGCCGGTGCCGTGCGCCTCGA | ||

| Rif1247Bf | CCGCAGCAGCGGTTGCTGCTCGA | Rifamycin | 70 |

| Rif1247Br | GTCCCGGTGCCGTGCGCCTCGA |

Table 3.

Detection of new KS1 to KS4 sequences in S. arenicola strains based on degenerate primers used to create clone libraries and specific primers used as PCR probes

| Strain | Originc | T-RFPL cluster | Sequence detection ind: |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New KS1 |

New KS2 |

New KS3 |

New KS4 |

Rif-KSb (Sare1247b) |

||||||||

| deg | spec | deg | spec | deg | spec | deg | spec | deg | spec | |||

| CNB-458 | BA | I | NT | + | NT | + | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNH-643a | BA | I | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| CNH-646 | BA | I | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNH-877 | BA | I | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNH-905a | BA | I | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| CNR-107 | Guam | I | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNR-425 | Guam | I | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNQ-884a | Guam | II | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| CNR-075a | Guam | II | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| CNR-416 | Guam | II | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNS-205a | Palau | I | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| CNR-964a | Palau | I | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| CNS-051 | Palau | I | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNS-340 | Palau | I | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNH-718 | RS | I | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNH-713 | RS | III | NT | + | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNH-719 | RS | III | NT | + | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNH-721a | RS | III | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| CNH-725a | RS | III | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| CNH-996 | SC | I | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNP-105 | SC | I | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNP-193 | SC | I | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

| CNH-964a | SC | IV | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| CNP-152a | SC | IV | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| CNP-173 | USVI | I | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | − | NT | + |

Strains from which clone libraries were created using degenerate PCR primers.

Instances where degenerate (deg) and specific (spec) primers did not agree are bold.

BA, Bahamas; RS, Red Sea; SC, Sea of Cortez; USVI, U.S. Virgin Islands.

+, sequence detected; −, sequence not detected; NT, not tested.

KS transcript analysis.

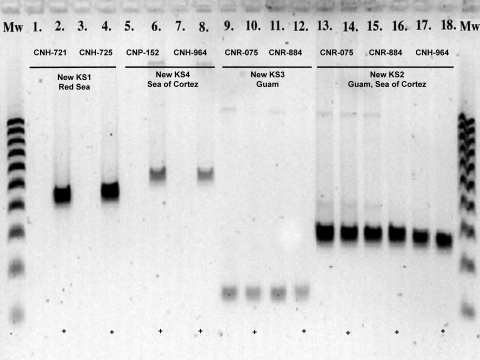

PCR probing of cDNA using primers specific for the new KS3 sequence yielded bands of the correct size on all days tested (3, 7, and 14) for both strains from Guam (CNR-075 and CNR-884) when cultured in medium C1 (Fig. 2). Sequence verification confirmed that the targeted pathway had been expressed. The expression of the new KS2 sequence in strains CNR-075 (Guam), CNR-884 (Guam), and CNH-964 (Sea of Cortez) also was verified on all days tested. The new KS4 sequence detected in the Sea of Cortez strains CNP-152 and CNH-964 was not expressed on day 3; however, sequence-verified expression was observed on day 14 for both strains (data not shown). No PCR products related to the new KS1 sequence could be amplified from cDNA derived from the Red Sea strains CNH-721 and CNH-725 at any time point using primers specific for these sequences. All six strains tested positive for the expression of the rifamycin KS on day 3, while control PCRs targeting the 16S rRNA gene generated negative results for all cDNA samples, indicating undetectable levels of genomic DNA.

Fig. 2.

Transcription analysis of ketosynthase (KS) sequences in Salinispora arenicola strains. Results are shown for day 3. Lanes 1 and 3, PCR amplification of new KS1 sequences from cDNA generated from strains CNH-721 and CNH-725. Lanes 2 and 4, positive controls (443 bp). Lanes 5 and 7, PCR amplification of new KS2 sequences from cDNA generated from strains CNP-152 and CNH-964. Lanes 6 and 8, positive controls (532 bp). Lanes 9 and 11, PCR amplification of new KS3 sequences from cDNA generated from strains CNR-075 and CNR-884. Lanes 10 and 12, positive controls (118 bp). Lanes 13, 15, and 17, PCR amplification of new KS4 sequences from strains CNR-075, CNR-884, and CNH-964. Lanes 14, 16, and 18, positive controls (267 bp). +, positive controls generated by PCR amplification of genomic DNA using KS-specific primers. Mw, molecular weight ladder (100 to 1,000 bp).

Secondary metabolite analysis.

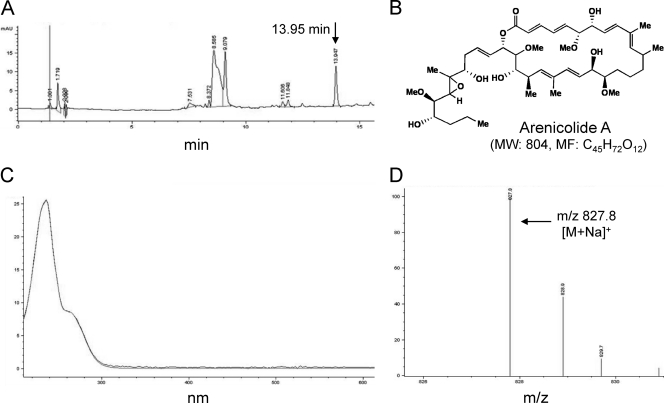

The cluster II strain CNR-075 that was isolated from Guam and tested positive for the expression of the new KS3 sequence was cultured in 1 liter, confirmed for KS3 expression, and extracted with ethyl-acetate. LC-MS analysis of the crude extract revealed the presence of a compound with a mass, UV spectrum, and molecular weight that corresponds precisely with that previously reported for the polyketide-derived secondary metabolite arenicolde A (Fig. 3). This compound originally was reported from the cluster II S. arenicola strain CNR-005 (28) and also was previously detected in the remaining cluster II strains CNQ-884 and CNR-416 as part of a separate study (13). The presence of the new KS3 sequence in all four S. arenicola strains that produce arenicolide A, coupled with our inability to detect this sequence in non-arenicolide-producing strains (Table 3), supports a link between this sequence and arenicolide A biosynthesis. Exhaustive chemical analyses of strain CNR-075 from a culture expressing the new KS2 sequence (Fig. 2) and strains CNH-964 and CNP-152 expressing the new KS4 sequence (day 14) (data not shown) failed to detect the presence of any polyketide-derived secondary metabolites that could be associated with these sequences.

Fig. 3.

Secondary metabolite analysis of S. arenicola strain CNR-075. (A) LC-MS trace (254 nm) of ethyl acetate extract with a peak corresponding to arenicolide A at 13.95 min. (B) Structure of arenicolide A. (C) UV absorbance spectrum of peak at a retention time of 13.95 min overlaid with arenicolide A standard (similarity score, 99.82%). (D) MS profile of the peak at a retention time of 13.95 min shows a molecular ion plus sodium adduct with a molecular weight of 827.8, which corresponds to that of arenicolide A plus sodium.

DISCUSSION

It has become increasingly clear that individual bacterial species can be recovered from global collection sites (2). What is less clear is the distribution of specific functional traits among geographically distinct populations of bacteria. Bacterial secondary metabolites represent a class of functional traits that remain largely undefined in terms of their population-level geographic distributions. We have addressed this question by analyzing PKS gene diversity among six geographically distinct populations of the marine actinomycete S. arenicola. The results provide evidence that subpopulations from specific locations maintain distinct sets of biosynthetic genes and thus reveals that location can influence secondary metabolism.

Terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) was employed as the primary analytical tool to compare the diversity of type I polyketide synthase genes among six S. arenicola populations. Unlike past studies that pioneered the used of this technique to target community-level biosynthetic gene diversity (25, 26), the present study targeted a single species that is essentially clonal at the 16S rRNA level and revealed clear evidence of clustering based on geographic origin. These clusters are comprised of subpopulations from Guam (cluster II), the Red Sea (cluster III), and the Sea of Cortez (cluster IV) that have significantly different T-RFLP patterns from those of the remainder of the strains, which fall into cluster I and include representatives from all six collection sites (Fig. 1). In total, 10 of 30 strains from three of the six collection sites yielded location-specific T-RFLP patterns, suggesting that endemic secondary metabolite gene profiles can be a relatively common feature of a broadly distributed bacterial species. However, it cannot be ruled out that these patterns would break down if a larger sample size was used.

The location specificity of T-RFLP clusters II to IV, coupled with the fact that PKS genes are known to be acquired by horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (8, 16), suggests that the secondary metabolite gene repertoires maintained by these subpopulations have been influenced by the local gene pool. However, further studies are needed to support this concept. All six strains from Guam were derived from independent sediment samples collected on different dates with the exception of strains CNR-075 and CNR-425, which originated from the same sample yet fall into two different T-RFLP clusters (I and II, respectively). While fine-scale spatial variability has been observed previously among functional genes in sediment bacterial communities (23), the results reported here provide some of the first evidence of centimeter-scale spatial variability in the secondary metabolite gene profiles maintained within a bacterial population.

In a prior study, evidence of species-specific secondary metabolite production was linked to biosynthetic genes that appeared to be acquired by HGT and was used to suggest that secondary metabolism played a role in Salinispora species diversification (13). The S. arenicola strains employed in the present study were clonal at the 16S level with the exception of the six strains derived form the Sea of Cortez, which all possessed one of two single-nucleotide changes previously identified as sequence types A and B (12). While the two Sea of Cortez strains comprising KS cluster IV both belong to 16S sequence type B, two additional B sequence types (strains CNP-193 and CNP-105) fall in cluster I. Thus, there does not appear to be a link between these single-nucleotide changes and the PKS genes maintained by the strains. It remains possible, however, that the strains comprising the three outlier KS clades (II to IV) represent nascent diversification events that cannot yet be detected using traditional phylogenetic markers. The detection of subpopulation T-RFLP clustering may help to explain what were termed accessory metabolites, i.e., secondary metabolites that are not consistently observed from any one species, in a prior study (13).

An analysis of the KS sequences cloned from representatives of the four T-RFLP clusters led to the detection of four new sequence types (Table 1, new KS1 to KS4) that have not previously been observed in S. arenicola (9, 20). The new KS3 and KS4 sequences were not detected in any strains outside their respective T-RFLP clusters (II and IV) when PCR primers specifically targeting these sequences were used (Table 3). The limited distributions of these sequences could be explained by a number of hypotheses, including recent acquisition or insufficient selective advantage to drive broader dissemination. However, it cannot be ruled out that similar sequences occur in strains outside these clusters yet remained undetected due to the limited number of clones sequenced.

All of the new KS sequences share low levels of amino acid identity (51 to 74%) with homologs from experimentally characterized biosynthetic pathways and thus cannot be used to make predictions about the potential structures of any associated secondary metabolic products (9). Interestingly, the new KS4 sequences amplified from the Sea of Cortez strains are distantly, yet most closely, related to KS sequences associated with the recently discovered trans-AT PKS genes in the leinamycin pathway (24). Phylogenetic analyses place the S. arenicola new KS4 sequences in a trans-AT KS clade (data not shown) and provide intriguing evidence for the presence of an uncommon biosynthetic paradigm that is best known among nonactinomycete bacterial symbionts (21).

All strains employed in this study, with the exception of CNR-964, CNS-340, and CNS-441, were previously analyzed for secondary metabolite production using culture-based methods (13). The four cluster II strains from Guam were unique in these analyses, in that they were the only strains observed to produce polyketide-derived macrolides in the arenicolide series (28). Given that the primers used in this study were designed to detect KS sequences associated with this class of secondary metabolites, the arenicolide biosynthetic pathway may contribute to, or be sufficient for, the distinct T-RFLP pattern observed for these strains. The detection of arenicolide A in a culture of the cluster II strain CNR-075 (Fig. 3), in conjunction with the expression of the new KS3 sequence observed in these strains (Fig. 2), provides evidence that this sequence and compound are linked. The observation that two additional strains from Guam (CNR-107 and CNR-425) were assigned to a different cluster (I), were not observed to produce compounds in the arenicolide class (13), and did not yield a PCR product when probed using primers specific for the associated KS sequence (Table 3) further supports this link. Additional genetic experiments will be required, however, before a formal link between compound and pathway can be drawn.

An analysis of the S. arenicola CNS-205 genome sequence revealed that only 8 of 25 predicted KS sequences were observed in the clone library generated from this strain. KS cloning inefficiencies have been observed previously in cultures (9) and environmental samples (25), and in this case they may be due to the preferential binding of the degenerate primers to certain templates. This possibility is supported by the observation that primers specific for KS sequences in the rifamycin biosynthetic pathway amplified these sequences in all four cases in which they were not amplified with the degenerate primers (Table 3). However, testing higher primer concentrations and different annealing temperatures and levels of degeneracy failed to rectify this issue (data not shown). It also is possible that the GC-rich (70%) and highly repetitive content of the Salinispora genome facilitates a level of secondary structure formation that limits primer binding. This was verified in silico using single-stranded S. arenicola KS sequences, which were calculated to fold and create secondary structures even at the highest annealing temperature tested (88°C). Interestingly, our inability to detect all predicted KS sequences is not reflected in the T-RFLP studies where a 111-bp KS sequence associated with the rifamycin biosynthetic pathway was detected in all T-RFLP traces (see Table S2 and Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) even though it was not observed in all clone libraries. Although cloning failed to capture all KS sequences in control experiments, this technique consistently captured the same sequences from the same strains (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

We currently know little about how functional traits such as secondary metabolism affect the diversity, distributions, and ecological adaptations of marine bacteria. The observation that new biosynthetic gene diversity was detected in two of the four T-RFLP clusters (II and IV, respectively) provides additional support for the use of this approach as a screening strategy for natural product discovery (25). The sequencing and PCR probing results corroborate the T-RFLP analyses and provide further evidence that subpopulations of bacteria can maintain distinct sets of biosynthetic genes. The location specificity of these subpopulations provides new evidence for endemism linked to secondary metabolism in marine bacteria.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (to A.E.), the German Research Foundation (DFG) (to S.L.), and the National Institutes of Health (GM085770 and GM086261 to P.R.J. and CA0448480 to W.F.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 1 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Altschul S. F., et al. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cho J.-C., Tiedje J. M. 2000. Biogeography and degree of endemicity of fluorescent pseudomonas strains in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5448–5456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coleman M. L., et al. 2006. Genomic islands and the ecology and evolution of Prochlorococcus. Science 311:1768–1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Edlund A., Hardeman F., Jansson J. K., Sjoling S. 2008. Active bacterial community structure along vertical redox gradients in Baltic Sea sediment. Environ. Microbiol. 10:2051–2063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Egert M., Friedrich M. W. 2003. Formation of pseudo-terminal restriction fragments, a PCR-related bias affecting terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of microbial community structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2555–2562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fischbach M. A., Walsh C. T. 2006. Assembly-line enzymology for polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: logic, machinery, and mechanisms. Chem. Rev. 106:3468–3496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ginolhac A., et al. 2004. Phylogenetic analysis of polyketide synthase I domains from soil metagenomic libraries allows selection of promising clones. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5522–5527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ginolhac A., et al. 2005. Type I polyketide synthases may have evolved through horizontal gene transfer. J. Mol. Evol. 60:716–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gontang E., GaudÍncio S., Fenical W., Jensen P. 2010. Sequence-based analysis of secondary-metabolite biosynthesis in marine actinobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:2487–2499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gontang E. A., Fenical W., Jensen P. R. 2007. Phylogenetic diversity of gram-positive bacteria cultured from marine sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3272–3282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jensen P. R., Gontang E., Mafnas C., Mincer T. J., Fenical W. 2005. Culturable marine actinomycete diversity from tropical Pacific Ocean sediments. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1039–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jensen P. R., Mafnas C. 2006. Biogeography of the marine actinomycete. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1881–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jensen P. R., Williams P. G., Oh D. C., Zeigler L., Fenical W. 2007. Species-specific secondary metabolite production in marine actinomycetes of the genus Salinispora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1146–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Julien B., et al. 2000. Isolation and characterization of the epothilone biosynthetic gene cluster from Sorangium cellulosum. Gene 249:153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Legendre P., Legendre L. 1983. Canonical analysis, p. 575–633 In Legendre P., Legendre L. (ed.), Numerical ecology. Elsevier Science BV, Amsterdam, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lopez J. 2003. Naturally mosaic operons for secondary metabolite biosynthesis: variability and putative horizontal transfer of discrete catalytic domains of the epothilone polyketide synthase locus. Mol. Genet. Genomics 270:420–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maldonado L. A., et al. 2005. Salinispora arenicola gen. nov., sp. nov. and Salinispora tropica sp. nov., obligate marine actinomycetes belonging to the family Micromonosporaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55:1759–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McAlpine J. B., et al. 2005. Microbial genomics as a guide to drug discovery and structural elucidation: ECO-02301, a novel antifungal agent, as an example. J. Nat. Prod. 68:493–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Müller-Schneider T. 1994. The visualization of structural change by means of correspondence analysis, p. 267–279 In Greenacre M., Blasius J. (ed.), Correspondence analysis in the social sciences. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 20. Penn K., et al. 2009. Genomic islands link secondary metabolism to functional adaptation in marine Actinobacteria. ISME J. 3:1193–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Piel J. 2010. Biosynthesis of polyketides by trans-AT polyketide synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27:996–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sakai T., Asai N., Okuda A., Kawamura N., Mizui Y. 2004. Pladienolides, new substances from culture of Streptomyces platensis Mer-11107. II. Physico-chemical properties and structure elucidation. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 57:180–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scala D. J., Kerkhof L. J. 2000. Horizontal heterogeneity of denitrifying bacterial communities in marine sediments by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1980–1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tang G. L., Cheng Y. Q., Shen B. 2004. Leinamycin biosynthesis revealing unprecedented architectural complexity for a hybrid polyketide synthase and nonribosomal peptide synthetase. Chem. Biol. 11:33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wawrik B., Kerkhof L., Zylstra G. J., Kukor J. J. 2005. Identification of unique type II polyketide synthase genes in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2232–2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wawrik B., et al. 2007. Biogeography of actinomycete communities and type II polyketide synthase genes in soils collected in New Jersey and central Asia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2982–2989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Welch R. A., et al. 2002. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:17020–17024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Williams P. G., Miller E. D., Asolkar R. N., Jensen P. R., Fenical W. 2007. Arenicolides A-C, 26-membered ring macrolides from the marine actinomycete Salinispora arenicola. J. Org. Chem. 72:5025–5034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.