Abstract

Streptomyces soil isolates exhibiting the unique ability to oxidize atmospheric H2 possess genes specifying a putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase. This study was undertaken to explore the taxonomic diversity and the ecological importance of this novel functional group. We propose to designate the genes encoding the small and large subunits of the putative high-affinity hydrogenase hhyS and hhyL, respectively. Genome data mining revealed that the hhyL gene is unevenly distributed in the phyla Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Acidobacteria. The hhyL gene sequences comprised a phylogenetically distinct group, namely, the group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase genes. The presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria constituting group 5 were shown to possess a hydrogenase gene cluster, including the genes encoding auxiliary and structural components of the enzyme and four additional open reading frames (ORFs) of unknown function. A soil survey confirmed that both high-affinity H2 oxidation activity and the hhyL gene are ubiquitous. A quantitative PCR assay revealed that soil contained 106 to 108 hhyL gene copies g (dry weight)−1. Assuming one hhyL gene copy per genome, the abundance of presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria was higher than the maximal population size for which maintenance energy requirements would be fully supplied through the H2 oxidation activity measured in soil. Our data indicate that the abundance of the hhyL gene should not be taken as a reliable proxy for the uptake of atmospheric H2 by soil, because high-affinity H2 oxidation is a facultatively mixotrophic metabolism, and microorganisms harboring a nonfunctional group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase may occur.

INTRODUCTION

Hydrogenases catalyze the interconversion of H2 to protons and electrons (H2 ↔ 2H+ + 2e−). Under physiological conditions, these metalloenzymes couple H2 oxidation to respiration or reduce protons as a way to disperse accumulated reducing equivalents (21). Hydrogenases are divided into three different classes on the basis of the metal content of their catalytic sites: [NiFe]-, [FeFe]-, and [Fe]-hydrogenases (55, 56). Among these, [NiFe]-hydrogenases from the domain Bacteria are the most numerous and the most extensively studied. These hydrogenases usually are O2 tolerant or are transiently inactivated following O2 exposure (20), a feature that argues for their integration into biofuel cells (58) and biohydrogen production (27).

Phylogenetic analysis of the gene sequences encoding the structural subunits of [NiFe]-hydrogenases has revealed the occurrence of 4 distinct groups (55). Group 1 comprises membrane-bound hydrogenases coupling H2 oxidation to aerobic or anaerobic respiration in bacteria and archaea. Group 2 includes two subclasses of cytoplasmic hydrogenases: the cyanobacterial uptake hydrogenases (group 2a), which recycle H2 evolved from nitrogenase, and the H2 sensor hydrogenases (group 2b), which control the transcription of hydrogenase genes in aerobic H2-oxidizing bacteria (35). Hydrogenases belonging to group 3 are physiologically bidirectional and include four subclasses defined on the basis of additional subunits that are able to bind cofactors such as NAD, F420, and NADP. These bidirectional hydrogenases either are found in methanogenic archaea (51) or act as electron valves in the photosynthetic electron transport of cyanobacteria (2). The function of H2-evolving hydrogenases in group 4 is to dissipate reducing equivalents generated through the fermentation of low-potential carbon, such as carbon monoxide and formate (47).

Recent evidence for a fifth group of [NiFe]-hydrogenases was obtained by analyzing the H2 oxidation activity of Streptomyces spp. isolated from soil (13). Gene sequences specifying a putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase were detected in Streptomyces avermitilis and several Streptomyces isolates displaying an unusually high affinity H2 oxidation activity (apparent Km [Km(app)], <100 parts per million by volume [ppmv]) and the unique ability to oxidize atmospheric H2 (13). These microorganisms contribute to the uptake of H2 by soil, which represents the main sink for atmospheric H2 (15, 18). Interestingly, inactivation of the putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase caused a significant reduction in the growth yield of Mycobacterium smegmatis (5). Expression of the genes encoding auxiliary and structural components of this hydrogenase increased under starvation conditions without an exogenous H2 supply, suggesting that the genes encoding the putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase conferred on M. smegmatis the ability to scavenge atmospheric H2 (5). Based on the Gibbs free energy of atmospheric H2 oxidation activity and bacterial maintenance energy requirements, Conrad (10) estimated that the H2 uptake activity of soil typically observed in the environment would sustain a maximal population of 6 × 107 H2-oxidizing bacteria per gram of soil. Virtually nothing is known about the taxonomic diversity, distribution, and abundance of high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria in the environment, impeding evaluation of the extent of their contribution to the global budget of atmospheric H2.

The objective of this study was to explore the ecological importance of high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria by using the genes specifying the putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase in S. avermitilis as functional biomarkers. Although gene sequences homologous to those encoding putative high-affinity hydrogenases have been observed in the genomes of Ralstonia eutropha (50), Frankia spp. (36), and Thermomicrobium roseum (60), the taxonomic diversity of high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria in publicly available genome databases has not been thoroughly analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene sequence data mining and phylogenetic analyses.

Sequences similar to those of genes encoding the auxiliary and structural components of the putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase in S. avermitilis were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (1). Nucleic acid sequences were assembled into 14 gene-specific databases and were imported into the ARB software package (37). Imported sequences were translated in silico, and the amino acid sequences were aligned using ClustalW (52). The alignments were optimized manually, and functional amino acid sequence motifs in the structural (HhySL) and auxiliary (HypABCDEFX) components of [NiFe]-hydrogenases were examined in order to validate the sequences (7). Conserved sequence motifs in the accessory proteins of [NiFe]-hydrogenase are described in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The accession numbers of the sequences retrieved from the NCBI database are provided in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The amino acid sequences of open reading frames (ORFs) 1 to 4 and HhyS were imported into SignalP, version 3.0, in order to search for N-terminal signal peptides (3, 19). The amino acid sequence of ORFs 1 to 4 was searched for putative transmembrane helices using the TMHMM (transmembrane protein topology based on the hidden Markov model) package (31).

Phylogenetic trees of amino acid sequences translated from the gene specifying the large subunit of [NiFe]-hydrogenases were constructed with neighbor-joining and maximum-parsimony algorithms by using the ARB software package (37).

16S rRNA gene sequences were retrieved from the genomes of 23 presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria. The sequences were imported into the SILVA database, containing aligned 16S rRNA sequences with a minimum length of 1,200 bp for bacteria (44). Pairwise distance matrices (23 by 23) were computed (37) to obtain the similarity scores of all possible combinations of 16S rRNA gene, hhyL gene, and HhyL amino acid sequences. Comparisons between the percentages of similarity of all hhyL and HhyL pairs and the sequence similarities of the 16S rRNA genes of the same bacteria were performed by regression analysis (n = 252). This pairwise similarity score analysis has recently been utilized to establish a similarity score threshold value for particulate methane monooxygenase gene (pmoA) sequences in methanotrophic bacteria at the species level (17).

Soil samples.

Soil samples were collected in ecosystems encompassing a broad range of climate and soil properties (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Soil samples collected in a deciduous forest (Mainz, Germany), an agricultural area (Heidelberg, Germany), a paddy field (Fuyang, China), a hyperarid desert (Arava, Israel), an arid desert (Avdat, Israel), and peatland (Loppi, Finland) were recently used to study the thermal deactivation of high-affinity hydrogenase activity (9). Other soil samples were collected in Siberian grassland and in experimental afforestation plots maintained for 30 years under the influence of five tree species: Arolla pine (Pinus sibirica), Scots pine (Pinus silvestris), Norway spruce (Picea abies), birch (Betula fruticosa), and aspen (Populus tremula) (40, 41). The soil samples were sieved (mesh size, <2 mm) and stored at 4°C for more than 2 years. For the measurement of H2 oxidation activity, 1 to 3 g of soil was suspended in 5 ml Tris buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.0]).

H2 oxidation activity.

Before H2 uptake activity was measured, 60-ml vials containing soil suspensions were sealed with rubber stoppers and were flushed for 30 min with synthetic air (80% N2 and 20% O2). Standard H2 gas (1,000 ppmv ± 2%; Messer Schweiz AG, Switzerland) was then added to the headspace of the bottles to obtain an initial mixing ratio of 1.5 to 1.8 ppmv H2. The decrease in the H2 mixing ratio was monitored as a function of time by analyzing aliquots (0.5 ml) of the headspace air in a gas chromatograph with a reduction gas detector as described previously (49). Vials were continuously agitated at 100 rpm on an orbital shaker kept at 25°C to enhance the transfer of H2 from the gas to the liquid phase. Apparent first-order H2 uptake rate constants were obtained by integrating the logarithmic decrease in the headspace H2 mixing ratio. H2 concentrations were typically measured over 3 h, and the H2 oxidation activity was proportional to the amount of soil. The reproducibility of the H2 analyses was assessed before and over the course of each set of experiments by repeated analysis of certified standard H2 gas (2.0 ppmv ± 5% H2; Messer Schweiz AG, Switzerland), and standard deviations were typically <5%. No significant H2 uptake was observed for blank experiments with sterile Tris buffer. H2 oxidation activity measurements were performed in triplicate.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and cloning of hhyL genes.

Genomic DNA was extracted from 500-mg soil samples using the SL Buffer(I) and Enhancer solution provided in the NucleoSpin soil kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were disrupted using a FastPrep system (Thermo Scientific) with 1 burst at 5.0 m s−1 for 30 s. DNA was eluted in 50 μl SE buffer (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG, Germany) and was serially diluted (1:5, 1:10, and 1:100). PCRs were performed in 50-μl reaction volumes containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 0.2 μM primers NiFe-244f and NiFe-1640r (13), 20 μg of bovine serum albumin (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany), 2.5 U DNA polymerase (AccuPrime Taq DNA polymerase system; Invitrogen GmbH, Germany), and 2 μl diluted DNA. The reactions were performed using a Primus thermal cycler (MWG-Biotech AG, Germany) as follows: 94°C for 5 min; 10 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 65°C for 1 min, with a decrease in steps of 0.5°C/cycle, and 68°C for 1 min; 20 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 57°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 1 min; and a final extension for 10 min at 68°C. PCR-amplified hhyL genes from soil samples were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector system (Promega GmbH, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Recombinant colonies were manually picked and shipped to GATC Biotech AG (Germany) for plasmid extraction; PCR amplification using primers T7f and M13r, covering regions flanking the insert; and double-strand DNA sequencing. A total of 107 hhyL gene sequences were edited and assembled using the DNAStar software package and were compared with the GenBank database using a standard nucleotide-nucleotide BLAST search (1). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were defined at an arbitrary evolutionary distance of ≤10%, resulting in 54 OTUs.

Quantitative PCR of hhyL genes.

The copy number of hhyL genes in soil was determined by quantitative PCR using primers NiFe-244f and NiFe-568r (12). PCR-amplified hhySL genes (∼3 kb) from Streptomyces avermitilis DSMZ 46492 were used to generate a quantitative PCR standard. A dilution series of the PCR-amplified DNA was made to generate a standard curve of hhySL covering 30 to 3.0 ×109 copies of the template per assay, quantified by using PicoGreen (Quant-iT PicoGreen; Invitrogen GmbH, Germany). Quantitative PCR was performed using the iCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.) with a soil DNA extract dilution series (1:5, 1:10, and 1:100) as the template. The reaction mixture (25 μl) contained 12.5 μl SYBR green Jump-Start Taq ReadyMix, 0.5 μM each primer, 3.0 mM MgCl2, and 5.0 μl template DNA. The thermal protocol used was 94°C for 6 min, followed by 45 cycles at 94°C for 35 s, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s, with plate reading at 86.5°C for 10 s. The threshold cycles (CT) of all reactions were determined by analysis of PCR kinetics with iCycler software (version 2.3.1370). Specific amplification of the hhyL gene was confirmed by melting curve analysis. The data reported are the averages of quantifications performed using triplicate DNA extracts.

Theoretical population size of high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria in soil.

The theoretical population size of high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria in soil was estimated based on the theoretical maintenance energy consumption rate and the free energy of atmospheric H2 oxidation, using the following model formulated by Conrad (10): N = 1.4 × 1014 (−ΔG)d/mE, where N is the theoretical population size of H2-oxidizing bacteria in soil (expressed as the number of cells g of soil [dry weight]−1), 1.4 × 1014 is a constant expressing the density of bacterial cells containing 1 mol carbon (number of cells [mol of C biomass]−1), ΔG is the Gibbs free energy of atmospheric H2 oxidation (−199 kJ mol of H2−1), d is the measured H2 oxidation rate (mol of H2 g of soil [dry weight]−1), and mE is the energy maintenance requirement of the population (kJ [mol of C biomass]−1). This model provides an estimate of the maximal population for which the H2 oxidation reaction fully supplies mE. The parameter mE is dependent primarily on temperature and was estimated using the following model derived by Tijhuis et al. (54):

where R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1) and T is the temperature (K).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All hhyL gene sequences determined in this study have been deposited in GenBank (4) with accession numbers HM029252 to HM029358.

RESULTS

Genome data mining for the putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase.

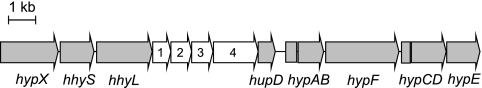

The genome of S. avermitilis, which exhibits the unusual ability to oxidize atmospheric H2, includes a unique gene cluster specifying a putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase (13). This gene cluster comprises 14 genes encoding the structural and auxiliary components of the putative metalloenzyme (Fig. 1). We designated the ORFs specifying putative proteins with similarity to the [NiFe]-hydrogenase small and large subunits hhyS and hhyL. These gene designations were chosen according to the recommended hydrogenase gene nomenclature (56), where hhyS or hhyL stands for high-affinity hydrogenase small or large subunit. No N-terminal signal peptide recognized by the twin-arginine translocation apparatus was detected in the small subunit, indicating that the [NiFe]-hydrogenase either is soluble or is anchored to an internal membrane-bound electron acceptor. The eight ORFs hypABCDEFX and hupD encode putative proteins with similarity to hydrogenase pleiotropic maturation proteins and endopeptidase, respectively. The HypABCDEF proteins are responsible for the assembly of active-site constituents and their insertion into the large subunit of the hydrogenase (7, 34, 57). ORFs 1 to 4 specify hypothetical proteins of unknown function in which neither a consensus N-terminal signal peptide cleavage site nor a putative transmembrane helix was detected.

Fig. 1.

Arrangement of auxiliary and structural genes of the putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase in S. avermitilis.

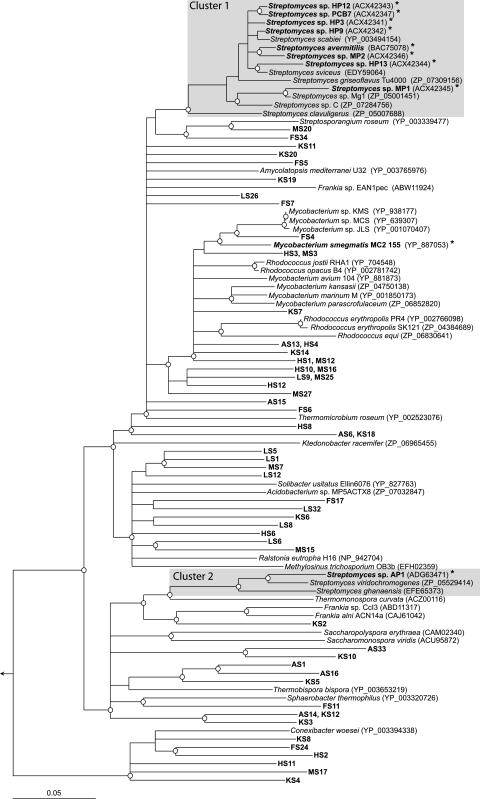

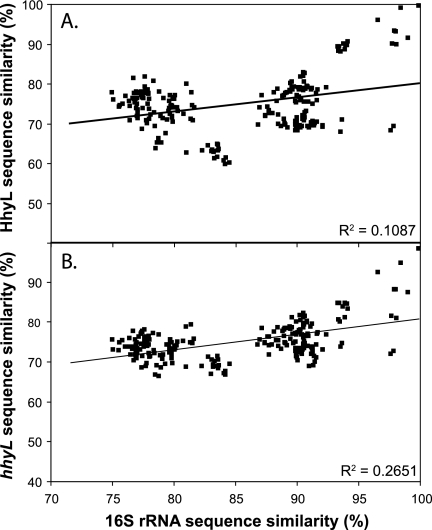

The S. avermitilis hhyL gene, encoding the large subunit of the putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase, was used to search public gene sequence data. The sequences were retrieved from a genome sequencing project for microorganisms isolated from diverse ecological niches, including contaminated soils and humans (Table 1). The HhyL-like translated amino acid sequences were added to the extensive [NiFe]-hydrogenase large-subunit sequence database of Vignais and Billoud (55), and they clustered with sequences specifying the putative high-affinity hydrogenases in H2-oxidizing streptomycetes isolated from soil (Fig. 2). This analysis substantiated the definition of the phylogenetically distinct group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenases (13) and revealed that homologous genes for hhyL are unevenly distributed across the phyla Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, and Chloroflexi. According to phylogenetic analysis, the conserved L1 and L2 motifs, including the four cysteine residues of HhyL, differed from the conserved motif in the large subunit of [NiFe]-hydrogenases belonging to groups 1 to 4 (Fig. 3). The pairwise sequence similarity scores of 16S rRNA genes and HhyL or hhyL were not correlated (Fig. 4), leading to incongruence between classifications in the hhyL and 16S rRNA gene-based phylogeny. For instance, hhyL gene sequences showed 75 to 97% and 72 to 87% pairwise similarity scores in Streptomyces spp. and Frankia spp., respectively, and did not make up species-specific monophyletic clusters (Fig. 2). The hhyL gene sequences of Streptomyces spp. formed two clusters. Cluster 1 comprises S. avermitilis and other soil isolates displaying high-affinity H2 oxidation activity, while cluster 2 encompasses S. ghanaensis, S. viridochromogenes, and Streptomyces sp. AP1 (Fig. 2). Strain AP1 was isolated from arid desert soil and showed high-affinity H2 oxidation activity, with a Km(app) of 30 ppmv H2 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Owing to the unusual high-affinity H2 oxidation activity of Streptomyces isolates possessing the hhyL gene, the microorganisms possessing group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenases are defined as “presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria.” Genes encoding additional [NiFe]-hydrogenases belonging to groups 1 to 3 were also detected in a number of representatives (Table 1).

Table 1.

Identification and sources of microorganisms possessing genes specifying auxiliary and structural components of the group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase

| Phylum and speciesa | Sourceb | Auxiliary gene(s) not detectedc | Other [NiFe]-hydrogenase(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria | |||

| Streptomyces avermitilis(hypX+) | Soil | ||

| Streptomyces scabiei(hypX+) | Soil | ||

| Streptomyces sviceus(hypX+) | Soil | ||

| Streptomyces griseoflavus | Soil | Group 3b | |

| Streptomyces sp. Mg1 (hypX+) | Soil | Group 3b | |

| Streptomyces sp. C (hypX+) | Soil | ||

| Streptomyces clavuligerus | Soil | ||

| Streptomyces viridochromogenes(hypX+) | Soil | ORF3 | Group 1 |

| Streptomyces ghanaensis(hypX+) | Soil | ORF3 | |

| Mycobacterium sp. KMS | PAH-contaminated soil | Group 3b | |

| Mycobacterium sp. MCS | PAH-contaminated soil | Group 3b | |

| Mycobacterium sp. JLS | PAH-contaminated soil | Group 3b | |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis | Human smegma | Groups 2a, 3b | |

| Mycobacterium avium | Clinical isolate | hypA, hypB, hypC, hypD, hypE, hypF | |

| Mycobacterium kansasii | Clinical isolate | Group 3b | |

| Mycobacterium marinum M | Human isolate | Group 3b | |

| Mycobacterium parascrofulaceum | Clinical isolate | Group 3b | |

| Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 | Lindane-contaminated soil | Group 3b | |

| Rhodococcus erythropolis PR4 | Seawater | Group 3b | |

| Rhodococcus erythropolis SK121 | Human skin | hypA | Group 3b |

| Rhodococcus equi | Human abscess | Group 3b | |

| Rhodococcus opacus B4 | Gasoline-contaminated soil | Group 3d | |

| Frankia sp. EAN1pec | Root nodule | Group 1 | |

| Frankia sp. CcI3 | Root nodule | ORF3 | Groups 2a, 3b |

| Frankia alni ACN14a | Root nodule | ORF3 | Group 2a |

| Saccharopolyspora erythraea | Soil | ||

| Saccharomonospora viridis | Peat | ||

| Thermobispora bispora | Decaying manure | ORF4 | Groups 2a, 3b |

| Thermomonospora curvata | Straw | ORF3, ORF4, hypB | |

| Amycolatopsis mediterranei U32 | Soil | ||

| Streptosporangium roseum | Soil | hypB | Group 3b |

| Conexibacter woesei | Soil | ||

| Proteobacteria | |||

| Ralstonia eutropha H16 (hypX+) | Sludge | Groups 1, 2b, 3d | |

| Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b | Sediment, soil, and water | Groups 1, 2b, 3b | |

| Chloroflexi | |||

| Thermomicrobium roseum | Hot spring | ORF1 | |

| Sphaerobacter thermophilus | Thermophilic sewage sludge | ORF3, hypD, hypE, hypF | |

| Ktedonobacter racemifer | Soil | ||

| Acidobacteria | |||

| Acidobacterium sp. MP5ACTX8 | Acidic soil | ||

| Solibacter usitatus Ellin6076 | Grazed pasture | hypA | Groups 1, 3d |

Microorganisms possessing the hypX-like gene are identified (hypX+).

PAH, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon.

A list of the accession numbers of the auxiliary genes detected is provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Fig. 2.

Neighbor-joining tree of translated amino acid sequences from hhyL gene sequences retrieved from public databases, soil isolates, and soil clone libraries. Prefixes of hhyL clone sequences indicate the soil type, as follows: AS, arid desert; FS, paddy field; HS, agricultural area; KS, hyperarid desert; LS, peatland; MS, deciduous forest. Microorganisms in which high-affinity H2 oxidation activity was demonstrated are asterisked. Streptomyces clusters 1 and 2 are shaded. Bar, 0.05 change per amino acid position. Only the nodes supported by ≥50% of the bootstrap replicates are shown. Circles mark the nodes validated with the maximum-likelihood algorithm.

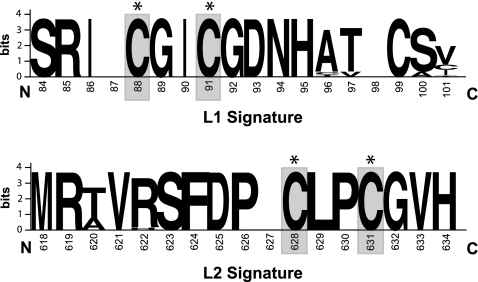

Fig. 3.

Consensus L1 and L2 signatures in the large subunit of the hydrogenase generated from the alignment of sequences comprising the group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase cluster using the Weblogo program (16). Amino acid residue positions in the HhyL sequence alignment are given below the letters. The overall height of the symbols indicates the relative frequency of each amino acid and the sequence conservation at each position. Asterisked, shaded C's represent the cysteine residues coordinating the NiFe cofactor in the large subunit of the hydrogenase. An alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences of selected group 1 to 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase large subunits is provided in File S1 in the supplemental material.

Fig. 4.

Correlation between the pairwise sequence similarity scores of HhyL and the 16S rRNA gene (A) and the hhyL gene and the 16S rRNA gene (B) in presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria with group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenases.

We searched the genome sequences of presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria for the [NiFe]-hydrogenase auxiliary genes of S. avermitilis. The sequences retrieved were assembled in gene-specific databases and were examined for functional amino acid sequence motifs after alignment (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Hydrogenase gene clusters comprising sequences homologous to the hypABCDEF-like genes and the four ORFs encoding hypothetical proteins of S. avermitilis were detected in 69% of the presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria (Table 1). However, auxiliary genes encoding critical components of the hydrogenase maturation apparatus were missing in Mycobacterium avium and Sphaerobacter thermophilus (Table 1). The hypX-like gene was detected only in Streptomyces spp. and in the soluble [NiFe]-hydrogenase (group 3) operon of Ralstonia eutropha. Except for the fact that hhySL and ORFs 1 to 3 always flanked each other, no consensus was observed in the arrangement of the genes encoding the auxiliary components of group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase. The genes encoding structural and auxiliary components of the hydrogenase are arranged within a single cluster in all the presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria except Thermonospora bispora and Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Environmental soil survey for the putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase.

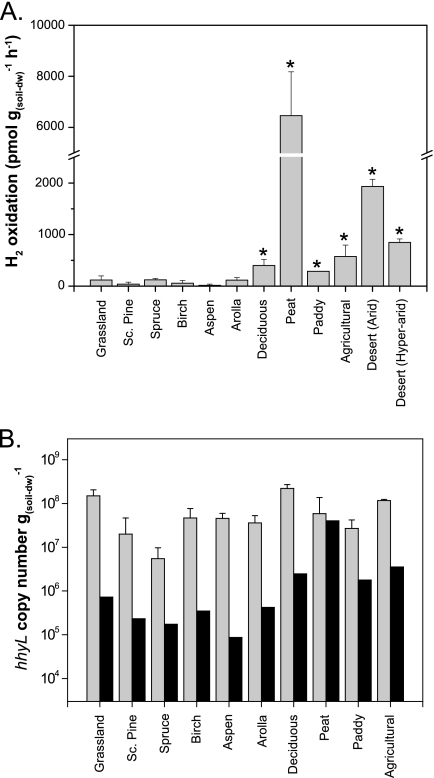

High-affinity H2 oxidation activity was analyzed in soil samples collected in ecosystems encompassing a broad range of climate and soil properties (Fig. 5A). The soil physicochemical parameters analyzed, including pH, nitrogen content, and carbon content, were not significantly correlated with H2 oxidation rates. Indeed, the soil samples displaying the highest H2 oxidation activity were collected in peatland and desert ecosystems encompassing extreme ranges in climate and physicochemical properties of soil (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Six clone libraries were generated on the basis of hhyL gene sequences amplified from soil samples collected in a deciduous forest, an agricultural area, a hyperarid desert, an arid desert, a paddy field, and peatland. Clone sequences were incorporated into the hydrogenase phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 5.

(A) H2 oxidation activities of soil samples collected in contrasting terrestrial ecosystems exposed to 1.5 ppmv H2. Asterisked soil samples were utilized for hhyL gene clone libraries. Sc. pine, Scots pine. (B) Copy number of the hhyL gene (shaded bars) and maximal population of high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria for which maintenance energy requirements would be fully supplied through the H2 oxidation activity measured in the soil (filled bars). dw, dry weight.

Measured soil H2 oxidation rates (Fig. 5A) were used to estimate the maximal population of high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria that could survive using H2 as an energy source (10). Based on the model, H2 oxidation would fully supply the maintenance energy requirements of 104 to 107 H2-oxidizing bacteria g of soil (dry weight)−1 (Fig. 5B). The abundance of presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria in soil was determined using a quantitative PCR assay targeting the hhyL gene. Soil samples contained 106 to 108 hhyL gene copies g of soil (dry weight)−1 (Fig. 5B). Assuming one hhyL gene copy per genome (55), the abundances of H2-oxidizing bacteria determined by quantitative PCR were thus generally larger than the theoretical maximal population size estimates. H2 oxidation activity was not proportional to the hhyL gene copy number detected in soil.

DISCUSSION

Compelling experimental evidence suggests that high-affinity H2-oxidizing Streptomyces spp. possessing the genes encoding a putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase are involved in the uptake of atmospheric H2 (13, 14). Quantitative assessment of the contribution of high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria to the budget of atmospheric H2 remains elusive, however, since virtually nothing is known about their abundance, diversity, and distribution in the environment. This study constitutes a first attempt to bridge this knowledge gap.

The putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase is distributed across different phyla and constitutes a phylogenetically distinct group, namely, the group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenases. The definition of this novel group was further supported by the conserved L1 and L2 signatures of the large subunit (Fig. 3), distinguishing the group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenases from those belonging to groups 1 to 4 (55). The presence of conserved ORFs 1 to 4 within the hydrogenase coding region and the unusual high-affinity H2 oxidation activity displayed by Streptomyces isolates possessing the genes encoding the putative metalloenzyme (13) are other unique features of group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenases. The novel hydrogenase was not detected in publicly available archaeal genome sequences. We propose the designations hhyS and hhyL for the gene sequences specifying the small and large subunits of [NiFe]-hydrogenases belonging to group 5. Consistent with the recommended hydrogenase gene nomenclature based on phylogenetic relationships (56), these gene designations are proposed to eliminate inconsistencies in the designation of the genes homologous to hhySL in current genome annotations.

The incongruence between 16S rRNA and hhyL gene sequence phylogenies (Fig. 4) implies a lateral inheritance of group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenases. Indeed, the potential lateral acquisition of group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenases was observed in analyses of the genome sequence data of R. eutropha (50), Frankia spp. (36), and Thermomicrobium roseum (60). According to the selfish-operon hypothesis, the arrangement of the auxiliary and structural genes of the hydrogenase within a single cluster constitutes an important factor promoting the diversification of presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria (33). Genes encoding factors involved in genetic mobility, a tRNA gene, and a phage motif typical of genomic islands (25) were observed in the chromosome region of a number of group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase gene clusters (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). The origin and functionality of a laterally inherited hydrogenase gene complex would require special attention in future investigations. With the exception of Streptomyces soil isolates (13, 14) and M. smegmatis (28), there has been no report on high-affinity H2 oxidation activity in microorganisms possessing group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenases. Frankia spp. have been shown to express the hhyL gene in soil, suggesting that these actinobacteria possess a functional group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase (36, 39). In contrast, R. eutropha H16 harbors a megaplasmid carrying the genes encoding group 1, 2, 3, and 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase isoenzymes and has been shown to be unable to oxidize atmospheric H2 (11, 50). Whether the genes specifying the putative high-affinity hydrogenase are functional in R. eutropha or not remains elusive, since strain HF500, defective in all but the group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase, showed no H2 oxidation activity (30). The putative high-affinity hydrogenase of R. eutropha might be cryptic, constituting a genetic reservoir that could potentially be activated following genetic modifications or could be expressed under particular growth conditions.

The function of the auxiliary genes of group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase was predicted based on the current stage of knowledge about the hydrogenase maturation apparatus in Escherichia coli and R. eutropha (7, 34, 57). Auxiliary proteins designated HypABCDEF are involved in the assembly of active-site components into the large subunit. The endopeptidase HupD cleaves the C-terminal extension of the large subunit after nickel insertion, triggering the final folding and assembly of the polypeptide with the small subunit. However, it must be mentioned that conserved amino acid motifs shown to be essential for the activity of [NiFe]-hydrogenase maturation proteins in Escherichia coli (7) were absent from some auxiliary gene sequences retrieved from the genomes of Streptomyces spp. (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Whether the whole set of genes identified in S. avermitilis (Fig. 1) is essential for group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase activity or not remains to be established, especially for hypX and ORFs 1 to 4, whose physiological function is unknown. The hypX-like gene encodes a putative protein, HypX, that has been shown to confer oxygen tolerance on the soluble [NiFe]-hydrogenase in R. eutropha H16 through the attachment of an additional cyanide ligand to the active site (6) and to participate in the maturation of the large subunit of the H2 uptake hydrogenase in Rhizobium leguminosarum (45). The hypX gene was detected only in the hydrogenase gene clusters of Streptomyces representatives (Table 1), suggesting that they synthesize hydrogenases with unusual biochemical properties. The conservation of ORFs 1 to 4 in the hydrogenase gene clusters of presumptive H2-oxidizing bacteria suggests that their function could be linked to the activity of group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase (61). Since ORFs 1 to 4 are not found in group 1 to 4 [NiFe]-hydrogenase gene clusters, biochemical characterization of these hypothetical proteins would provide valuable information on the biological functions of [NiFe]-hydrogenases belonging to group 5. The deduced amino acid sequence of ORF1 comprises two conserved redox-active CxxC motifs, designated “rheostat in the active site” due to the influence of the residues separating the two cysteines on the redox function of the enzymes (8). Coupling of ORFs 1 to 4 with the structural subunits of group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase to mediate electron flow is thus conceivable. The hypABCDEF genes coordinate the NiFe cofactor and the assembly of the hydrogenase. The HypC, HypD, HypE, and HypF proteins participate in the transfer of the Fe-(CN−)2-(CO) moiety to the precursor of the large subunit of [NiFe]-hydrogenase, while HypA and HypB are involved in nickel storage and insertion (7, 34, 57). Only HypCDEF have been shown to be essential for a functional hydrogenase. Indeed, hypA and hypB mutants are readily complemented by the addition of exogenous nickel (>0.5 mg liter−1) in cultivation media, while microorganisms deficient in hypCDEF have been shown to lack hydrogenase activity (23, 24, 38, 43). Bioavailable nickel concentrations of 0.5 to 6 mg kg−1 have been detected in sewage sludge-amended soils (53), while low- and high-affinity nickel transport systems allow microorganisms to satisfy their demands for this metal (42). Thus, the concentration of bioavailable nickel in soil should be sufficient to complement a hypAB gene deficiency in H2-oxidizing bacteria. In contrast, the occurrence of a functional hydrogenase is questionable in M. avium and S. thermophilus, which possess only the group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenase and lack the hypABCDEF and hypDEF-like genes, respectively (Table 1).

Soil samples collected in different ecosystems were analyzed for H2 oxidation activity and the occurrence of presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria using the hhyL gene as a functional biomarker. Among the sampling sites selected, peatland and agricultural ecosystems were recently investigated for annual H2 fluxes. These ecosystems are natural sinks for atmospheric H2, with annual average deposition velocities of 0.057 and 0.031 cm s−1, respectively (32, 48). Accordingly, peat displayed a higher H2 oxidation activity than agricultural soil (Fig. 5A). Differences in H2 oxidation activity may reflect H2-oxidizing bacterial populations that are divergent in terms of abundance and diversity. This concept was already proposed in an extensive soil survey revealing that the H2 oxidation potential of soil was proportional to substrate-induced respiration and potential nitrification rates (22). The incongruence between the phylogenies of the 16S rRNA and hhyL gene sequences observed in newly identified presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria (Fig. 4) impaired the identification of sequences retrieved from soil at the taxonomic level. Nevertheless, the detection of the hhyL gene in every soil sample indicated that high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria are ubiquitous in terrestrial ecosystems.

A first attempt to quantify presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria in soil, using quantitative PCR targeting hhyL genes, was made. The number of hhyL gene copies was compared to the maximal population theoretically sustained with the H2 oxidation activity measured. The fact that the abundance of hhyL gene copies was higher than the theoretical population estimates (Fig. 5B) reflects the lack of discrimination between active and inactive H2-oxidizing bacteria inherent in the hhyL gene detection approach. Indeed, high-affinity H2 oxidation is a facultative metabolism induced under definite growth conditions (5, 13, 14). Atmospheric H2 is likely an alternative substrate providing complementary energy sources (13), and therefore, presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria may grow heterotrophically without expressing hydrogenase genes. Moreover, our in silico analysis revealed that the expression of a functional high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase remains questionable in several bacteria possessing the hhyL gene (Table 1). The copy number of the hhyL gene in soil is therefore not a reliable proxy for assessing high-affinity H2 oxidation activity in soil. Notwithstanding these limitations, application of the quantitative PCR approach showed that presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria are abundant and ubiquitous in soil, supporting further investigations aimed at defining the environmental control of high-affinity hydrogenase gene expression and activity.

Conclusion.

Presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria are taxonomically diverse and encompass representatives isolated from various ecological niches. A reason for the wide distribution of the hhyL gene may be its specific function in mixotrophic metabolism—the ability to acquire energy from organic and inorganic substrates—providing microorganisms with metabolic versatility for long-term survival or growth (13, 26, 46). Interestingly, several presumptive high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria do possess a high-affinity carbon monoxide dehydrogenase conferring the ability to oxidize atmospheric carbon monoxide mixotrophically (29). The utilization of H2 and CO as complementary energy sources should provide a metabolic benefit, enabling microorganisms to colonize oligotrophic environments as well as thriving and making up an important fraction of microbial assemblages in nutrient-rich environments, as has been observed across a succession gradient of volcanic deposits (59). Such a potentially wide distribution of high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria was supported by the presence of hhyL genes in soil collected in contrasting terrestrial ecosystems. The abundance of hhyL gene copies in soil supports the notion that high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria contribute to the uptake of atmospheric H2 by soil. However, the lack of discrimination between active and inactive components of high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacterial assemblages impairs quantitative assessment of the extent to which these microorganisms contribute to the uptake of atmospheric H2 by soil. There are significant gaps in our current knowledge about the physiological and mechanistic aspects of the uptake of atmospheric H2 by soil. We anticipate that the availability of high-affinity H2-oxidizing isolates and the genetic information presented in this article will stimulate future investigations to elucidate the regulation and biochemical properties of group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenases, the ecophysiology of high-affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria, and ultimately environmental control of the uptake of atmospheric H2 by soil. A gene-driven mutagenesis approach will be crucial to confirming the functions of the genes specifying the auxiliary and structural components of group 5 [NiFe]-hydrogenases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

P.C. was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Fonds Québécois de Recherche sur la nature et les technologies and the Max Planck Society. This research was partially funded by a grant from the European Network for Atmospheric Hydrogen observations and studies (Eurohydros) to R.C.

Soil samples collected in the Siberian artificial afforestation experiment and desert ecosystems were kindly provided by Oleg V. Menyailo and Roey Angel. We are also grateful to Melanie Klose for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 8 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Appel J., Phunpruch S., Steinmüller K., Schulz R. 2000. The bidirectional hydrogenase of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 works as an electron valve during photosynthesis. Arch. Microbiol. 173:333–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bendtsen J. D., Nielsen H., von Heijne G., Brunak S. 2004. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340:783–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Benson D. A., Karsch-Mizrachi I., Lipman D. J., Ostell J., Sayers E. W. 2009. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D26–D31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berney M., Cook G. M. 2010. Unique flexibility in energy metabolism allows mycobacteria to combat starvation and hypoxia. PLoS One 5:e8614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bleijlevens B., Buhrke T., van der Linden E., Friedrich B., Albracht S. P. J. 2004. The auxiliary protein HypX provides oxygen tolerance to the soluble [NiFe]-hydrogenase of Ralstonia eutropha H16 by way of a cyanide ligand to nickel. J. Biol. Chem. 279:46686–46691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Böck A., King P. W., Blokesch M., Posewitz M. C. 2006. Maturation of hydrogenases. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 51:1–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chivers P. T., Prehoda K. E., Raines R. T. 1997. The CXXC motif: a rheostat in the active site. Biochemistry 36:4061–4066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chowdhury S. P., Conrad R. 2010. Thermal deactivation of high-affinity H2 uptake activity in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42:1574–1580 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Conrad R. 1999. Soil microorganisms oxidizing atmospheric trace gases (CH4, CO, H2, NO). Indian. J. Microbiol. 39:193–203 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Conrad R., Aragno M., Seiler W. 1983. The inability of hydrogen bacteria to utilize atmospheric hydrogen is due to threshold and affinity for hydrogen. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 18:207–210 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Constant P., Chowdhury S. P., Hesse L., Conrad R. 31 May 2011 Co-localization of atmospheric H2 oxidation activity and high affinity H2-oxidizing bacteria in non-axenic soil and sterile soil amended with Streptomyces sp. PCB7. Soil Biol. Biochem. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.05.009.

- 13. Constant P., Chowdhury S. P., Pratscher J., Conrad R. 2010. Streptomycetes contributing to atmospheric molecular hydrogen soil uptake are widespread and encode a putative high-affinity [NiFe]-hydrogenase. Environ. Microbiol. 12:821–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Constant P., Poissant L., Villemur R. 2008. Isolation of Streptomyces sp. PCB7, the first microorganism demonstrating high-affinity uptake of tropospheric H2. ISME J. 2:1066–1076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Constant P., Poissant L., Villemur R. 2009. Tropospheric H2 budget and the response of its soil uptake under the changing environment. Sci. Total Environ. 407:1809–1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J.-M., Brenner S. E. 2004. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14:1188–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Degelmann D. M., Borken W., Drake H. L., Kolb S. 2010. Different atmospheric methane-oxidizing communities in European beech and Norway spruce soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:3228–3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ehhalt D. H., Rohrer F. 2009. The tropospheric cycle of H2: a critical review. Tellus 61B:500–535 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Emanuelsson O., Brunak S., von Heijne G., Nielsen H. 2007. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat. Protoc. 2:953–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fontecilla-Camps J. C., Volbeda A., Cavazza C., Nicolet Y. 2007. Structure/function relationships of [NiFe]- and [FeFe]-hydrogenases. Chem. Rev. 107:4273–4303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frey M. 2002. Hydrogenases: hydrogen-activating enzymes. Chembiochem 3:153–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gödde M., Meuser K., Conrad R. 2000. Hydrogen consumption and carbon monoxide production in soils with different properties. Biol. Fertil. Soils 32:129–134 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hube M., Blokesch M., Böck A. 2002. Network of hydrogenase maturation in Escherichia coli: role of accessory proteins HypA and HybF. J. Bacteriol. 184:3879–3885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jacobi A., Rossmann R., Böck A. 1992. The hyp operon gene products are required for the maturation of catalytically active hydrogenase isoenzymes in Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 158:444–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Juhas M., et al. 2009. Genomic islands: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:376–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kiessling M., Meyer O. 1982. Profitable oxidation of carbon monoxide or hydrogen during heterotrophic growth of Pseudomonas carboxydoflava. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 13:333–338 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim J. Y. H., Jo B. H., Cha H. J. 2010. Production of biohydrogen by recombinant expression of [NiFe]-hydrogenase 1 in Escherichia coli. Microb. Cell Fact. 9:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. King G. M. 2003. Uptake of carbon monoxide and hydrogen at environmentally relevant concentrations by mycobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7266–7272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. King G. M., Weber C. F. 2007. Distribution, diversity and ecology of aerobic CO-oxidizing bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kleihues L., Lenz O., Bernhard M., Buhrke T., Friedrich B. 2000. The H2 sensor of Ralstonia eutropha is a member of the subclass of regulatory [NiFe] hydrogenases. J. Bacteriol. 182:2716–2724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., Sonnhammer E. L. L. 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305:567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lallo M., Aalto T., Laurila T., Hatakka J. 2008. Seasonal variations in hydrogen deposition to boreal forest soil in southern Finland. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35:L04402 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lawrence J. 1999. Selfish operons: the evolutionary impact of gene clustering in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9:642–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lenz O., et al. 2010. H2 conversion in the presence of O2 as performed by the membrane-bound [NiFe]-hydrogenase of Ralstonia eutropha. Chemphyschem 11:1107–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lenz O., Friedrich B. 1998. A novel multicomponent regulatory system mediates H2 sensing in Alcaligenes eutrophus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:12474–12479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leul M., Normand P., Sellstedt A. 2007. The organization, regulation and phylogeny of uptake hydrogenase genes in Frankia. Physiol. Plant. 130:464–470 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ludwig W., et al. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maier T., Binder U., Böck A. 1996. Analysis of the hydA locus of Escherichia coli: two genes (hydN and hypF) involved in formate and hydrogen metabolism. Arch. Microbiol. 165:333–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mattsson U., Sellstedt A. 2000. Hydrogenase in Frankia KB5: expression of and relation to nitrogenase. Can. J. Microbiol. 46:1091–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Menyailo O. V., Hungate B. A., Abraham W.-R., Conrad R. 2008. Changing land use reduces CH4 uptake by altering biomass and activity but not composition of high-affinity methanotrophs. Global Change Biol. 14:2405–2419 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Menyailo O. V., Hungate B. A., Zech W. 2002. Tree species mediated soil chemical changes in a Siberian artificial afforestation experiment. Plant Soil 242:171–182 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mulrooney S. B., Hausinger R. P. 2003. Nickel uptake and utilization by microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:239–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Olson J. W., Mehta N. S., Maier R. J. 2001. Requirement of nickel metabolism proteins HypA and HypB for full activity of both hydrogenase and urease in Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 39:176–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pruesse E., et al. 2007. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned rRNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:7188–7196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rey L., et al. 1996. The hydrogenase gene cluster of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae contains an additional gene (hypX), which encodes a protein with sequence similarity to the N10-formyltetrahydrofolate-dependent enzyme family and is required for nickel-dependent hydrogenase processing and activity. Mol. Gen. Genet. 252:237–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rittenberg S. C., Goodman N. S. 1969. Mixotrophic growth of Hydrogenomonas eutropha. J. Bacteriol. 98:617–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sawers G. 1994. The hydrogenases and formate dehydrogenases of Escherichia coli. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 66:57–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schmitt S., Hanselmann A., Wollschläger U., Hammer S., Levin I. 2009. Investigation of parameters controlling the soil sink of atmospheric molecular hydrogen. Tellus 61B:416–423 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schuler S., Conrad R. 1990. Soils contain two different activities for oxidation of hydrogen. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 73:77–83 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schwartz E., et al. 2003. Complete nucleotide sequence of pHG1: a Ralstonia eutropha H16 megaplasmid encoding key enzymes of H2-based lithoautotrophy and anaerobiosis. J. Mol. Biol. 332:369–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thauer R. K., et al. 2010. Hydrogenases from methanogenic archaea, nickel, a novel cofactor, and H2 storage. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79:507–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tibazarwa C., et al. 2001. A microbial biosensor to predict bioavailable nickel in soil and its transfer to plants. Environ. Pollut. 113:19–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tijhuis L., Van Loosdrecht M. C. M., Heijnen J. J. 1993. A thermodynamically based correlation for maintenance Gibbs energy requirements in aerobic and anaerobic chemotrophic growth. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 42:509–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vignais P. M., Billoud B. 2007. Occurrence, classification, and biological function of hydrogenases: an overview. Chem. Rev. 107:4206–4272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vignais P. M., Billoud B., Meyer J. 2001. Classification and phylogeny of hydrogenases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:455–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vignais P. M., Colbeau A. 2004. Molecular biology of microbial hydrogenases. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 6:159–188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vincent K. A., et al. 2005. Electrocatalytic hydrogen oxidation by an enzyme at high carbon monoxide or oxygen levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:16951–16954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Weber C. F., King G. M. 2010. Distribution and diversity of carbon monoxide-oxidizing bacteria and bulk bacterial communities across a succession gradient on a Hawaiian volcanic deposit. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1855–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wu D., et al. 2009. Complete genome sequence of the aerobic CO-oxidizing thermophile Thermomicrobium roseum. PLoS One 4:e4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yanai I., Mellor J. C., DeLisi C. 2002. Identifying functional links between genes using conserved proximity. Trends Genet. 18:176–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.