Abstract

The Tinto River is an extreme environment located at the core of the Iberian Pyritic Belt (IPB). It is an unusual ecosystem due to its size (100 km long), constant acidic pH (mean pH, 2.3), and high concentration of heavy metals, iron, and sulfate in its waters, characteristics that make the Tinto River Basin comparable to acidic mine drainage (AMD) systems. In this paper we present an extensive survey of the Tinto River sediment microbiota using two culture-independent approaches: denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and cloning of 16S rRNA genes. The taxonomic affiliation of the Bacteria showed a high degree of biodiversity, falling into 5 different phyla: Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Acidobacteria, and Actinobacteria; meanwhile, all the Archaea were affiliated with the order Thermoplasmatales. Microorganisms involved in the iron (Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, Sulfobacillus spp., Ferroplasma spp., etc.), sulfur (Desulfurella spp., Desulfosporosinus spp., Thermodesulfobium spp., etc.), and carbon (Acidiphilium spp., Bacillus spp., Clostridium spp., Acidobacterium spp., etc.) cycles were identified, and their distribution was correlated with physicochemical parameters of the sediments. Ferric iron was the main electron acceptor for the oxidation of organic matter in the most acid and oxidizing layers, so acidophilic facultative Fe(III)-reducing bacteria appeared widely in the clone libraries. With increasing pH, the solubility of iron decreases and sulfate-reducing bacteria become dominant, with the ecological role of methanogens being insignificant. Considering the identified microorganisms—which, according to the rarefaction curves and Good's coverage values, cover almost all of the diversity—and their corresponding metabolism, we suggest a model of the iron, sulfur, and organic matter cycles in AMD-related sediments.

INTRODUCTION

Pyrite (FeS2) is the most abundant sulfide mineral in the Earth's crust. When it is exposed to air and water, its oxidation can be carried out with either atmospheric oxygen or ferric iron, according to equations 1 to 3.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Ferric iron has been shown to oxidize pyrite 18 to 170 times more rapidly than O2, producing water with a low pH and a high iron content. However, this step is limited by the rate of ferrous iron oxidation (equation 2), which is greatly increased (by up to 5 orders of magnitude) at low pH through the action of Fe-oxidizing chemolithoautotrophs (38), such as the bacteria Acidithiobacillus spp. and Leptospirillum spp. Furthermore, low pH facilitates metal solubilization, particularly that of cationic metals; therefore, acidic water tends to be highly metalliferous (24). Pyrite oxidation and ferrous iron oxidation are both processes that occur naturally, and indeed, natural acidic drainage has been identified in many locations (44). Mining in these areas is known to dramatically increase the ferrous iron oxidation rates (39).

The Tinto River is a natural acidic drainage environment. It rises in Peña de Hierro, in the core of the Iberian Pyritic Belt (IPB), and reaches the Atlantic Ocean at Huelva, Spain. The IPB is one of the largest massive sulfidic deposits on Earth (250 km long) and formed as a hydrothermal deposit during the Paleozoic accretion of the Iberian Peninsula (32). Although the IPB has been subjected to mining activities for thousands of years (45), a recent analysis has shown that the iron oxides present in its sedimentary deposits are the result of the metabolic activity of acidophilic prokaryotes (14). The Tinto River is an unusual extreme ecosystem due to its size (100 km long), constant acidic pH (mean pH, 2.3), and high concentration of heavy metals, iron, and sulfate in its waters, characteristics that make the Tinto River Basin comparable to acidic mine drainage (AMD) systems.

The Tinto River has been the focus of an increasing amount of research, including biogeochemistry (exploring the nature of the microbial communities associated with AMD), biotechnology (bioleaching processes), microbiology (acidic environments offer an almost unique opportunity to reveal habitat biological complexity), and Mars analogue studies (jarosite is a common mineral on both Mars and Earth). Consequently, much is already known about the microbiota inhabiting the water column (1, 15, 18, 43, 52). Microbial ecology studies have shown that ca. 80% of the prokaryotic diversity in the water is explained by the presence of three bacteria Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, Leptospirillum ferrooxidans, and Acidiphilium spp., all of which are involved in the iron cycle. Some other species related to the iron cycle have also been identified (i.e., Ferroplasma acidiphilum and Ferrimicrobium acidiphilum), but their low number suggests that they play a minor role in this cycle (18). Despite the low prokaryotic diversity, an unexpected degree of eukaryotic diversity has been found and is the principal contributor of biomass in this hostile river (1, 52).

Despite ecological interest in the underlying sediments, they have been studied only very sparsely and studies have mainly focused on methanogens (46). So far, no complete studies of the anaerobic microbial diversity have been undertaken. In this paper we present an extensive survey of the Tinto River anaerobic sediment microbiota, using culture-independent approaches targeting the small-subunit (SSU) rRNA such as PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and cloning of 16S rRNA genes. Furthermore, a model of the iron, sulfur, and organic matter cycles is proposed to elucidate the microbial ecology of AMD-related sediments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Field site description and sampling.

The acidic sediments studied are located in the Tinto River Basin (Huelva), in southwestern Spain. Samples were collected from two sampling sites, SN Dam (Universal Transverse Mercator [UTM], E715378-N4178002) and JL Dam (UTM, E715073-N4174390), in March 2008 and March 2009. Sediment cores (inner diameter, 7 cm; length, 45 cm) were taken with a sampler (Eijkelkamp Agrisearch Equipment, The Netherlands). The redox potential (E) and pH of the drill core samples were measured in situ with E and pH probes connected to a Thermo Orion 290A potentiometer placed into the fresh sediment just after extraction of the core. The cores were sliced according to both physicochemical gradients and visual aspects, and the slices were kept separate until processing in the laboratory.

Nucleic acid extraction from sediments.

Total DNA was extracted from 6 g of each slice of sediment using a FastDNA Spin kit (for soil) of Qbiogene, Inc. Adaptation of the commercial protocol was carried out to optimize it for sediments with high concentrations of heavy metals and a low biomass content. Samples were first resuspended in 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and sonicated to detach cells from the solid phase. The sediment was centrifuged at 500 × g for 1 min in order to remove larger particles; the supernatant was carefully removed and centrifuged again at 8,000 × g for 20 min. After the supernatant was discarded, the remaining pellet was resuspended in 10 ml 0.5 M EDTA, pH 8, and incubated overnight at 4°C to dissolve humic substances and remove heavy metals. After incubation, the sediment was washed with PBS and DNA extraction procedures were applied to the pellet.

DGGE from sediment samples.

DGGE analyses were carried out with samples from March 2008 to get a first insight into the microbial diversity of the sediments. The V3 to V5 variable regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified with primer sets 341F (GC)-907R (annealing temperature [Ta] = 52°C) for Bacteria and 622F (GC)-1100R (Ta = 42°C) for Archaea. Primers 341F (GC) and 622F (GC) included a GC clamp: 5′-CGC CCG CCG CGC CCC GCG CCC GTC CCG CCC CCG CCC-3′ (37). The amplification reaction was performed according to the Taq DNA polymerase protocol (Promega, Madison, WI). The PCR conditions were as follows: 10 min of initial denaturation at 94°C and 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 min and annealing at 52/42°C for 1 min and 72°C for 2 min, followed by 10 min of final primer extension. DGGE analysis was carried out using a D-Code universal detection system instrument (Bio-Rad) and a model 475 gradient former according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bio-Rad). Polyacrylamide (6%; 37.5:1 acrylamide-bisacrylamide) gels with a 30 to 60% urea-formamide denaturant gradient (100% urea-formamide contains 7 M urea and 40% deionized formamide) were used in 1× TAE (Tris-acetate-EDTA) buffer, pH 7.4, at 200 V for 4 h at 60°C. Gels were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV illumination. About 100 bands were cut from the gel with a sterile blade and placed in sterile vials with 100 μl of Milli-Q water. DNA was allowed to diffuse into the water at 4°C overnight. Five microliters of the eluate was used as a DNA template in a PCR mixture of 50 μl with the primers described above but without the GC clamp. A total of 51 bands (30 for Bacteria and 21 for Archaea) yielded sequences that were identified by using the Ribosomal Database Project and the ARB software package (34).

Clone library construction.

The 16S rRNA genes were amplified with the primer sets 27F-1492R (Ta = 57°C) for Bacteria and 25F-1492R (Ta = 52°C) for Archaea. The PCR conditions were as follow: 10 min of initial denaturation at 94°C and 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 min and annealing at 57/52°C for 1 min and 72°C for 2 min, followed by 10 min of final primer extension. PCR products were gel purified with a GFX PCR DNA and gel band purification kit (GE Healthcare) and cloned into Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells by using the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Recombinant clones were identified as white colonies on chromogenic indicator plates. Isolated clones were grown overnight in 1.5 ml of broth medium containing 100 mg of ampicillin per liter. Recombinant plasmids were retrieved by an alkaline lysis protocol (4), and the correct size of the inserts was verified by gel electrophoresis. Plasmid DNA of positive clones was screened by amplified rRNA gene restriction analysis (ARDRA) using endonuclease BfuCI (1 U, 4 h, 37°C) and grouped according to the restriction patterns obtained. Two members of each group were then sequenced using a BigDye sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Sequences were assembled using the DNABaser program, and prior to phylogenetic analysis, vector sequences flanking the 16S rRNA gene inserts were removed. Sequences were compared with those in NCBI databases using the Ribosomal Database Project (35) to identify the closest sequences. Clone sequences were checked for chimeras using the program Chimera Check from green genes (http://greengenes.lbl.gov/cgi-bin/nph-bel3_interface.cgi). Complete sequences (>1,400 bp) obtained in this study were added to a database of over 50,000 homologous prokaryotic 16S rRNA primary structures by using the alignment tool of the ARB software package. Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed by using the three algorithms implemented in the ARB package (34). A consensus tree was generated, and bootstrap analysis was performed.

An ARB package-generated distance matrix was used to assign sequences to operational taxonomic units (OTUs). The coverage of the clone libraries was calculated using the equation described by Hansen and Singleton et al. (21), and the sampling efficiency in the clone libraries was assessed using Analytic Rarefaction (version 1.3) software (http://www.uga.edu/strata/software/), originally described by Heck et al. (23). PAST software (version 1.82b) (20) was used to compute the statistical indexes for the archaeal and bacterial sequences in each sampling station.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences determined in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers. HQ730609 to HQ730756, HQ853235 to HQ853236, and HQ916664 to HQ916667, combining sequence and contextual data in compliance with the Genomic Standards Consortium (GSC) with the CDinFusion tool (51).

RESULTS

Physicochemical parameters of the sampling site.

Significant differences between both sampling sites (JL and SN) were observed (Table 1). JL cores were banded and showed local variations from oxidizing zones to reducing zones with a redox range of from 200 to −120 and a pH range of from 3.9 to 5.7. Meanwhile, the SN sampling site comprised only two layers and showed a more oxidized zone in the superficial layer defined by the occurrence of brownish Fe(III) (hydr)oxides, a positive redox potential (+200 mV), a low pH of 2 to 4, and a deeper layer with less oxidant or even reducing redox potential.

Table 1.

Physicochemical parameters of both simple sites over 2 years

| Subsample | Yr 2008 |

Yr 2009 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depth (cm) | pH | Redox potential (mV) | Depth (cm) | pH | Redox potential (mV) | |

| JL1 | 8 | 3.8 | 168 | 7 | 3.8 | 200 |

| JL2 | 11 | 3.9 | 69 | 12 | 4.6 | −13 |

| JL3 | 14 | 4 | 113 | 16 | 4 | 53 |

| JL4 | 26 | 4.4 | 8 | 22 | 4.1 | 12 |

| JL5 | 30 | 5.3 | −120 | 26 | 4.4 | 1 |

| JL6 | 33 | 4.9 | −27 | 33 | 5.7 | −132 |

| JL7 | 38 | 5.4 | −71 | 40 | 4.7 | −30 |

| SN1 | 21-26 | 3.9 | 200 | 25 | 2.3 | 255 |

| SN2 | 40-45 | 4 | −13 | 43 | 3.63 | 47 |

DGGE fingerprint analyses.

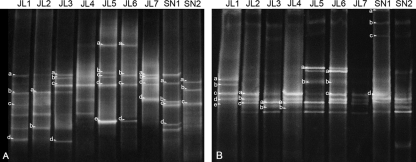

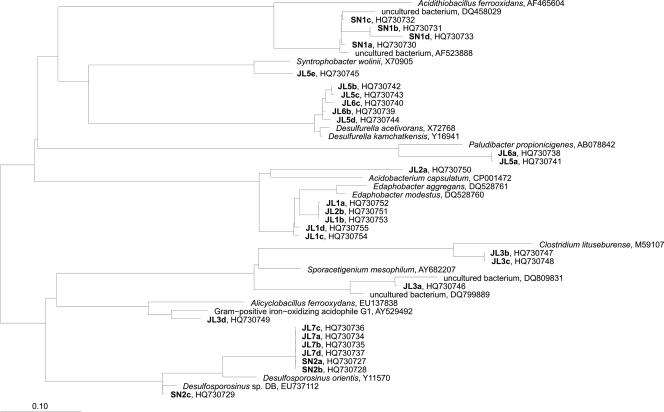

Both sites were analyzed at different depths to evaluate the level of diversity and to elucidate the possible correlation between the distribution of microorganisms with the physicochemical parameters. The bacterial fingerprint (Fig. 1 A) showed a relatively high number of bands compared to the low number found in previous water column studies (18). The pattern of bands differed between the two sampling sites and, on a global perspective, between depths. Bacteria sequences clustered in the phyla Proteobacteria (classes Gammaproteobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria), Bacteroidetes, Acidobacteria, and Firmicutes. As seen in Fig. 2, there is a correlation between layers and the phylogenetic affiliation of the sequences. In the surface layers of JL Dam (JL1 and JL2), sequences belong to the phylum Acidobacteria, which includes acidophilic bacteria typically found in soils. In the next layer (JL3), sequences belong to the phylum Firmicutes, clustering in the order Clostridiales (Sporacetigenium spp.) and Bacillales (Alicyclobacillus spp). In the deepest layers (JL5, JL6, JL7), extremely anaerobic organisms were found, including sulfate-reducing bacteria, such as Desulfurella and Desulfosporosinus spp. and Syntrophobacter spp., propionate- degrading syntrophic bacteria typically from neutral pH environments, as well as Paludibacter spp., a fermenting Bacteroidetes. In the surface layer of the SN Dam (SN1), sequences were identified as belonging to the family Acidithiobacillaceae (Gammaproteobacteria class). In the deeper layer (SN2), organisms were related to the spore-forming sulfate-reducing bacteria Desulfosporosinus spp.

Fig. 1.

DGGE fingerprints of 16S rRNA obtained with domain-specific primers for Bacteria (A) and Archaea (B). Lane names are shown according to depth and sample site.

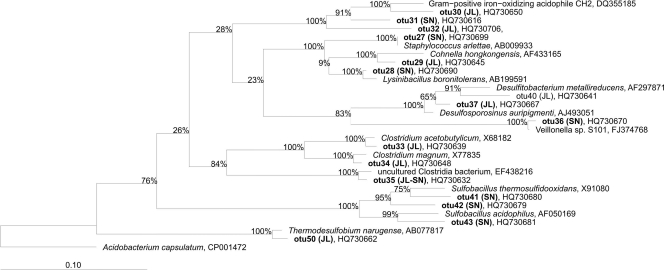

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic affiliations of bacterial DGGE sequences obtained from Tinto River samples. The phylogenetic tree was generated using parsimony with the ARB program. The bar indicates a 10% estimated sequence divergence. The sequences from Tinto River are indicated in boldface type, and the designations after the organism names or identifiers are GenBank accession numbers.

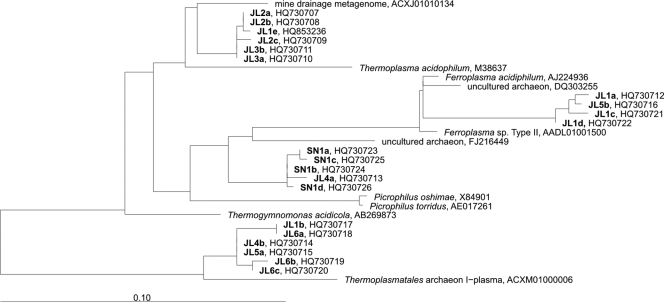

The archaeal fingerprints (Fig. 1B) had a lower number of bands than the Bacteria, and their phylogenetic distribution was less varied; in fact, all the Archaea sequences cluster in the phylum Euryarchaeota, in the order Thermoplasmatales, independently of the sample site and depth (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic affiliations of archaeal DGGE sequences obtained from Tinto River samples. The phylogenetic tree was generated using parsimony with the ARB program. The bar indicates a 10% estimated sequence divergence. The sequences from Tinto River are indicated in boldface type, and the designations after the organism names or identifiers are GenBank accession numbers.

Bacterial clone library diversity.

A total of 489 sequences (>1,400 bp) were grouped into 44 phylotypes or OTUs on the basis of 97% sequence similarity (42). The taxonomic affiliation of the cloned sequences revealed a high degree of biodiversity. The microorganisms fell into four different phyla with at least 20 different genera. Although PCR-based methods are not quantitative, Proteobacteria and Firmicutes were the most represented phyla in our study, each comprising 17 phylotypes (38.6%), followed by the Acidobacteria and Actinobacteria with 5 OTUs each (11.4%).

(i) Proteobacteria. (a) Alphaproteobacteria.

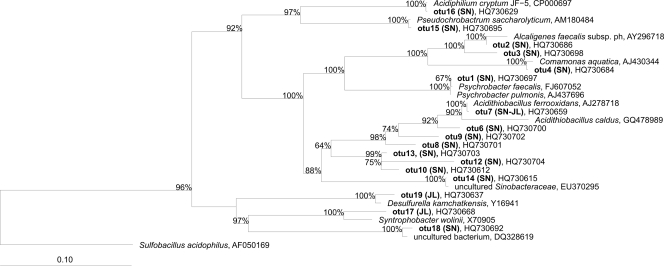

OTU 16 was affiliated with Acidiphilium cryptum, a heterotrophic species which is widely distributed in bioleaching and AMD environments and capable of respiring ferric to ferrous iron by oxidizing reduced carbon compounds (25). OTU 15 is related to Pseudochrobactrum asaccharolyticum, a denitrifying bacterium capable of fermentative metabolism (Fig. 4) (28).

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic affiliations of 16S rRNA sequences of the Proteobacteria phylum obtained from Tinto River samples. A consensus phylogenetic tree was generated using parsimony, neighbor-joining, and maximum likelihood analyses with different sets of filters, which showed stable branching. One hundred bootstrap replicates were performed. The bar indicates a 10% estimated sequence divergence. The sequences from Tinto River are indicated in boldface type, and the designations after the organism names or identifiers are GenBank accession numbers.

(b) Betaproteobacteria.

OTUs 2 and 3 were assigned to the genus Alcaligenes, with OTU 2 identified as Alcaligenes faecalis. Most of the strains are capable of anaerobic respiration with nitrite, but not nitrate, as a sole electron acceptor (40). OTU 4 was affiliated with Comamonas aquaticus, which has a respiratory metabolism using oxygen as the terminal acceptor and is capable of nitrate reduction (49).

(c) Gammaproteobacteria.

OTUs 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, and 13 clustered in the order Acidithiobacillales, of which OTUs 6 to 9 were affiliated with the genus Acidithiobacillus, and OTU 7 was identified as At. ferrooxidans, one of the most well-studied bioleaching bacteria, which derives energy mainly from the oxidation of reduced sulfur compounds and/or ferrous iron. Clones belonging to OTUs 10, 11, and 13 clustered into Acidithiobacillales group RCP1-48, which also has clones isolated from AMD systems. OTU 14 (uncultured Sinobacteraceae) could not be assigned to any described species but showed high similarity to uncultured microorganisms retrieved from acid environments, including the Tinto River, like clone with GenBank accession number EU370296. OTU 1 was affiliated with the genus Psychrobacter, which is related to clones isolated from sediments.

(d) Deltaproteobacteria.

OTU 17 was assigned to the genus Syntrophobacter and OTU 19 was identified as Desulfurella, both of which are implicated in the sulfur cycle. Members of the genus Syntrophobacter can use sulfate as an electron acceptor and oxidize propionate via the methylmalonyl coenzyme A pathway, and Desulfurella spp. are acid-tolerant sulfur-reducing bacteria detected in several acid environments as well as in AMD remediation bioreactors (27). OTU 18 clustered with an uncultured Bacteriovoraceae bacterium related to clones of the organism with GenBank accession number DQ328619 obtained from an extreme acid mine drainage sediment. Deltaproteobacteria were detected for the first time in AMD systems at the Richmond Mine (7), and since then they have been detected in some similar systems (8, 9, 16, 22, 48, 50).

(ii) Firmicutes.

The sequenced clones of the Firmicutes (Fig. 5) were distributed evenly over two relevant environmental subgroups, classes Bacilli and Clostridia. All the OTUs could be identified at least at the genus level as Staphylococcus (OTU 27), Lysinibacillus (OTU 28), Cohnella (OTU 29), Alicyclobacillus (OTUs 30 to 32), Clostridium (OTUs 33 to 35), Veillonella (OTU 36), Desulfosporosinus (OTU 37), Desulfitobacterium (OTUs 39 to 40), Sulfobacillus (OTUs 41 to 43), and Thermodesulfobium narugense (OTU 50). Several of these microorganisms are involved in the sulfur cycle. Sulfobacillus spp. are iron and sulfur oxidizers and grow over a broad range of temperatures (20 to 60°C). Desulfosporosinus spp. are obligately anaerobic, sulfate-reducing bacteria with the ability to sporulate, making them more resistant to acidic conditions (15). The majority of these clone sequences were 97% similar to Desulfosporosinus orientis, an organism that has previously been detected in other acidic environments, including acidic mining-impacted lake sediments (31). Desulfitobacterium spp. are very versatile microorganisms that can use a wide variety of electron acceptors, such as nitrate, sulfite, metals, humic acids, and halogenated organic compounds (48). Thermodesulfobium is a moderately thermophilic autotroph that is able to grow on H2/CO2 by sulfate respiration (36).

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic affiliations of 16S rRNA sequences of the Firmicutes phylum obtained from Tinto River samples. A consensus phylogenetic tree was generated using parsimony, neighbor-joining, and maximum likelihood analyses with different sets of filters, which showed stable branching. One hundred bootstrap replicates were performed. The bar indicates a 10% estimated sequence divergence. The sequences from Tinto River are indicated in boldface type, and the designations after the organism names or identifiers are GenBank accession numbers.

(iii) Acidobacteria.

Seven OTUs were associated with the Acidobacteria. OTUs 20 to 25 clustered in Acidobacterium group, and OTU 26 was related to the genus Edaphobacter. Although most of the clones were situated at considerable distances from the cultured members of this phylum, OTU 24 was identified as Acidobacterium capsulatum, a bacterium that formed Fe(II) under anoxic conditions at pHs ranging from 3 to 5 in association with the anaerobic respiration of glucose (12).

(iv) Actinobacteria.

All clones comprising OTUs 45 to 49 clustered into the family Acidimicrobiaceae, and although they could not be assigned to described species, they showed high similarity to uncultured microorganisms retrieved from AMD and a low similarity (90%) to Acidimicrobium ferrooxidans, a moderately thermophilic and acidophilic bacterium with a versatile metabolism (11): it oxidizes ferrous iron or reduces ferric iron as At. ferrooxidans.

Archaeal clone (Euryarchaeota) library diversity.

After chimeras and low-quality sequences were removed, a total of 78 archaeal clones distributed in 7 OTUs were retrieved. The clones retrieved from both sampling stations were phylogenetically homogeneous and belonged to the order Thermoplasmatales. Although SN clones could not be identified as belonging to any cultured species, JL clones belonged to the genus Thermoplasma, a moderately thermoacidophilic facultatively anaerobic archaeon which respires sulfur with organic carbon as an electron donor.

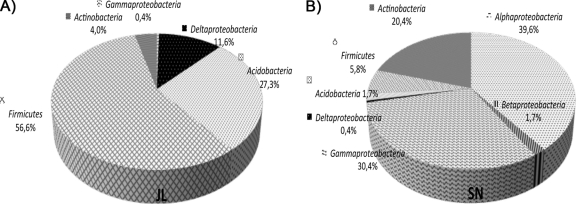

Relative distribution of the major phylogenetic groups in both sample sites.

The distribution of the major phylogenetic groups differed between sample sites (Fig. 6). Just 2 of 44 OTUs were shared between them. In JL Dam, a total of 249 sequences (>1,400 bp) were grouped into 18 OTUs. In SN Dam, a total of 240 sequences were grouped into 28 OTUs. In JL Dam, the group of Bacteria detected with the most numerous organisms was the phylum Firmicutes (56.6%), followed by the phylum Acidobacteria (27.3%) and the class Deltaproteobacteria (11.6%). Organisms of the Actinobacteria phylum (4%) and Gammaproteobacteria class (0.4%) were less abundant. In SN Dam, the phylum Proteobacteria (72.1%) was the most represented, mainly falling into the Alphaproteobacteria (39.6%) and Gammaproteobacteria (30.4%), followed by Actinobacteria (20.4%). Organisms of the phyla Firmicutes (5.3%) and Acidobacteria (1.7%) were present in low percentages.

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic composition of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene libraries of the two sample sites, JL Dam (A) and SN Dam (B).

Diversity indexes, coverage, and rarefaction analyses of the 16S rRNA gene libraries.

Rarefaction curves (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and Good's coverage values and diversity indexes (Table 2) were calculated separately for the Archaea and Bacteria in each sample site (SN and JL). Good's value, an estimation of the proportion of the population represented by the retrieved sequences (19), indicates high coverage of the archaeal and bacterial libraries at both sample sites, in agreement with the rarefaction curves. Dominance (D) values are similar in both samples sites but differ between the two domains. Whereas in Bacteria this value is close to 0, indicating that no OTUs predominate in the community, in Archaea, D values are higher, indicating the predominance of some OTUs in the sequence data set. In accordance with this, the Shannon-Wiever index value was lower.

Table 2.

Statistical indexes for bacterial and archaeal sequences in each sampling site using PAST software

| Characteristic |

Bacteria |

Archaea |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station JL | Station SN | Station JL | Station SN | |

| No. of sequences | 249 | 240 | 34 | 44 |

| No. of OTUs | 18 | 28 | 2 | 4 |

| Good's coverage value (%) | 98.4 | 96.3 | 97.1 | 100 |

| Shannon-Wiener index | 2.016 | 2.206 | 0.133 | 0.251 |

| Dominance (D) value | 0.226 | 0.196 | 0.943 | 0.870 |

DISCUSSION

Due to the important biotechnological, ecological, and astrobiological implications of AMD systems, these environments have been studied intensively during the last decade (3, 16, 43, 47). In addition, a useful review of carbon, iron, and sulfur metabolism in acidophilic microorganisms has recently been published (26). However, fewer studies have been performed on the anaerobic zones of these environments (5, 22), and some have focused exclusively on Fe-cycling bacteria (33) or methanogens (46).

DGGE fingerprint analysis of Tinto River sediments showed a good correlation between the physicochemical parameters of the different layers and the microorganisms inhabiting them. In JL Dam, the local variations within layers provide high physicochemical heterogeneity, and their influence can be stronger than that of depth. Despite this fact, a general tendency can be observed, with the layers varying from oxidizing and acidic conditions in the upper parts toward strongly reductant and slightly acidic ones in the deepest layers. Consequently, the dominant microorganisms shifted from Acidobacteria in the upper parts to fermentative organisms like Paludibacter spp. and Clostridium spp. when the conditions became less oxidizing and to sulfate-reducing bacteria like Desulfurella spp. and Desulfosporosinus spp. when the conditions were strongly reducing. A similar distribution was found in SN Dam, with variation of microorganisms from those related to the Acidithiobacillaceae family under oxidizing conditions to Desulfosporosinus spp. under reducing ones.

The phylogenetic analyses of 16S rRNA genes retrieved from the Tinto River sediments identified bacterial sequences from the Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Acidobacteria phyla and archaeal sequences from the Euryarchaeota/Thermoplasmatales group. Despite some similarities to sequences obtained in previous studies of Tinto River and other AMD systems (16, 17, 33, 43), some important differences could be identified. For example, no sequences related to Leptospirillum were found. This lithoautotrophic Fe(II) oxidizer has been shown to dominate microbial communities in extremely acidic AMD environments (41). Its preference to grow at a lower pH than At. ferrooxidans and its strict aerobic metabolism explain why it did not appear in Tinto River sediments, leaving the role of iron oxidizer in the oxidizing part of these moderate acidophilic sediments to Ferroplasma spp., At. ferrooxidans, Sulfobacillus spp., and Alicyclobacillus spp. in the anoxic parts (33).

Sulfate reduction and methanogenesis are usually inhibited in the presence of more electropositive electron acceptors like ferric iron (6, 10), which become the main electron acceptor for the oxidation of organic matter in anoxic AMD environments. So, the Fe(III)-reducing bacteria Acidiphilium spp., Acidobacterium spp., and Sulfobacillus spp. appear widely in the clones libraries. Some 27.3% of the bacteria were identified as Acidobacteria and were specifically related to A. capsulatum. With increasing pH, the solubility of iron decreases and sulfate reduction seems to play a more important role. Almost 20% of the sequences retrieved in JL Dam belonged to sulfate-reducing bacterium-related microorganisms: Syntrophobacter spp., Desulfosporosinus spp., Desulfurella spp., Desulfitobacterium spp., and Thermodesulfobium spp. Their prevalence should not be surprising, because in the presence of high concentrations of sulfate, as in the case of Tinto River, sulfate reducers dominate over methane producers when competing with each other over limited resources. Methanogens likely do not play a significant role in the ecology of the sediments. In fact, we failed to identify them by molecular approaches. However, their presence must not be ruled out: methane production was observed in situ and in the laboratory (data not shown). In addition, the occurrence of methanogens in JL Dam sediments has recently been described (46). At SN Dam, with a comparatively low pH, Fe(III) reducers Acidiphilium spp., Sulfobacillus spp., and At. ferrooxidans predominated.

From our data, other anaerobic metabolism apart from iron and sulfate reduction can be inferred. Several sequences related to potential nitrate or nitrite reducers such as Alcaligenes faecalis, Pseudochrobactrum spp., Pseudomonas spp., and Bacillus spp. were found. The concentrations of both nitrate and nitrite in the pore water of the sediments were below the detection limit (1 ppb), so nitrogen must be a limiting factor for bacterial growth in this environment and any input will be removed very quickly. In previous studies of the boreholes in the Tinto River (2), the fluid extracted from those underground habitats contained dissolved gases, such as H2, N2O, and CH4. Although the chemical origin of H2 was proposed to be by a water-rock interaction, the identification of H2-producing bacteria, such as Syntrophobacter spp. and Clostridium spp., introduces the possibility of a biological method of production of this gas.

In an extreme acidic, oxidizing, and cold bulk environment, we have found zones with slightly acidic pH and reducing redox potential. In accordance with this finding, sequences corresponding to microorganisms with forms of metabolism (such as sulfate and nitrate/nitrite reduction) that do not normally take place under the physicochemical conditions prevailing in the Tinto River were retrieved. Protection from acidity (29) and even the removal of oxygen by active respiration (30) have been described. In a similar way, the exothermic microbial oxidation of pyrite, which releases heat under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, could be the source of microenvironments with relatively high temperatures, explaining the presence of the moderately thermophilic organisms (Alicyclobacillus spp., Cohnella spp., Desulfurella spp., Thermodesulfobium spp., Sulfobacillus spp., and Thermoplasma spp.) found in the sediments.

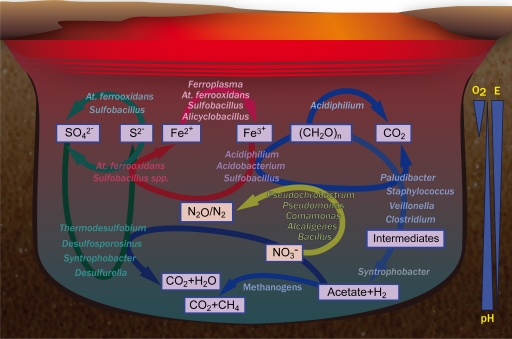

Geomicrobiologial model of sediments of Tinto River.

In this study, Tinto River sediments were analyzed by combining physicochemical data with molecular ecology studies. Rarefaction curves and Good's coverage values showed that almost all of the diversity was covered in our data set. So, through integration of geochemical and biological information, a model of the geomicrobiological processes that allow organisms to thrive in this extreme environment is suggested (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Geomicrobiological model of sediments from Tinto River, an AMD-related environment. The microorganisms involved in the iron, sulfur, and carbon cycles are indicated.

In contrast to previous studies on the water column, the molecular ecology of Tinto River sediments is not based exclusively on the iron cycle. In fact, it seems that the sulfur cycle and the removal of organic matter are predominant in this particular system. On the basis of the mineralogical composition of the Iberian Pyritic Belt, the main chemolithotrophic substrate available would be pyrite (FeS2), and that is the basis for the development of a complete community of microorganisms.

Iron in its reduced form, Fe(II), would be the main energy source of the autotrophic, facultatively anaerobic bacterium At. ferrooxidans, as well as members of the versatile genera Sulfobacillus and Alicyclobacillus and the archaeon Ferroplasma. As AMD solutions are iron rich because of the high solubility of iron at low pH, Fe(III) concentrations can exceed oxygen concentrations by several orders of magnitude even in surface layers, so Fe(III) can be widely used as an electron acceptor in microbial metabolism (12, 13). Thus, Fe(III) can be reduced, coupled to the oxidation of organic matter by heterotrophic acidophiles such as Acidiphilium spp., Sulfobacillus spp., Acidobacterium spp., or coupled to the oxidation of S0 under anoxic conditions by At. ferrooxidans and Sulfobacillus spp. These processes imply the regeneration of the ferrous iron as an energy source, completing the iron cycle with the consortia of microorganism thriving in these sediments.

The second set of crucial metabolites in this system are sulfur compounds. Sulfide is oxidized to sulfate by the chemolithotrophic bacterium At. ferrooxidans under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions and is coupled to Fe(III) reduction in the latter case. Sulfate reduction is carried out by bacteria such as Desulfosporosinus spp., Desulfurella spp., Thermodesulfobium spp., and Syntrophobacter spp. The presence of sulfate-reducing bacteria in the Tinto River system is evidence of microbial sulfate reduction at low pH, completing the sulfur cycle in Tinto River sediments.

Regarding the carbon cycle, both fermentative and respiring types of metabolism are present. There is a fermentative pathway that starts with organisms such as Paludibacter, Veillonella, Staphylococcus, and Clostridium spp. This creates a complex mix of intermediates, and some of them, e.g., propionate, can be used by the syntrophic bacteria Syntrophobacter spp., which generate hydrogen and acetate. These compounds act as substrates for the metabolism of sulfate-reducing bacteria and methanogens. Ferric iron can be respired by heterotrophic bacteria of the genera Acidiphilium, Sulfobacillus, and Acidobacterium, which oxidize organic matter, using it as an electron acceptor. Although their metabolism is not predominant, there are enough data to support the presence of methanogens (33, 46) that would complete the anaerobic degradation.

Our study implies that organic matter degradation must also be coupled to nitrate reduction mediated by organisms such as Alcaligenes faecalis, Pseudochrobactrum spp., Pseudomonas spp., and Bacillus spp. In fact, nitrous oxides have been measured in bioaugmented cultures of Tinto River sediments (data not shown).

In conclusion, the identification of microorganisms in this study and a detailed examination of their corresponding metabolism have allowed us to compile a model of the iron, sulfur, and organic matter cycles and their relation to microbial ecology in AMD-related sediments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación grant CTM2009-10521 to J. L. Sanz and grant CGL2009-11059 to R. Amils. Irene Sánchez-Andrea received a predoctoral fellowship from the same ministry.

Thanks are due to Hannah Marchant for English proofreading.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 1 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aguilera A., Manrubia S. C., Gomez F., Rodriguez N., Amils R. 2006. Eukaryotic community distribution and its relationship to water physicochemical parameters in an extreme acidic environment, Rio Tinto (southwestern Spain). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5325–5330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amils R., et al. 2008. Subsurface geomicrobiology of the Iberian Pyritic Belt. Subsurface geomicrobiology of the Iberian Pyritic Belt, p. 205–223 In Dion P., Nautiyal C. Shekhar. (ed.), Soil biology, vol. 13 Microbiology of extreme soils. Springer, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baker B. J., Banfield J. F. 2003. Microbial communities in acid mine drainage. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 44:139–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Birnboim H., Doly J. 1979. A rapid alkaline extraction method for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1513–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blothe M., et al. 2008. pH gradient-induced heterogeneity of Fe(III)-reducing microorganisms in coal mining-associated lake sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1019–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bodegom P. M., Scholten J., Stams A. J. M. 2004. Direct inhibition of methanogenesis by ferric iron. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49:261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bond P. L., Smriga S. P., Banfield J. F. 2000. Phylogeny of microorganisms populating a thick, subaerial, predominantly lithotrophic biofilm at an extreme acid mine drainage site. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3842–3849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brofft J. E., McArthur J. V., Shimkets L. J. 2002. Recovery of novel bacterial diversity from a forested wetland impacted by reject coal. Environ. Microbiol. 4:764–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruneel O., et al. 2005. Microbial diversity in a pyrite-rich tailings impoundment (Carnoulès, France). Geomicrobiol. J. 22:249–257 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Canfield D. E., Raiswell R., Bottrell S. 1992. The reactivity of sedimentary iron minerals toward sulfide. Am. J. Sci. 292:659–683 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clark D. A., Norris P. R. 1996. Acidimicrobium ferrooxidans gen. nov., sp. nov.: mixed-culture ferrous iron oxidation with Sulfobacillus species. Microbiology 142:785–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coupland K., Johnson D. B. 2008. Evidence that the potential for dissimilatory ferric iron reduction is widespread among acidophilic heterotrophic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 279:30–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Druschel G. K., Baker B. J., Gihring T. M., Banfield J. F. 2004. Acid mine drainage biogeochemistry at Iron Mountain, California. Geochem. Trans. 5:13–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fernández-Remolar D. C., et al. 2008. Underground habitats in the Río Tinto Basin: a model for subsurface life habitats on Mars. Astrobiology 8:1023–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. García-Moyano A., González-Toril E., Aguilera A., Amils R. 2007. Prokaryotic community composition and ecology of floating macroscopic filaments from an extreme acidic environment, Río Tinto (SW, Spain). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 30:601–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gonzalez-Toril E., et al. 2011. Geomicrobiology of La Zarza-Perrunal acid mine effluent (Iberian Pyritic Belt, Spain). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:2685–2694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gonzalez-Toril E., et al. 2003. Geomicrobiology of the Tinto River, a model of interest for biohydrometallurgy. Hydrometallurgy 71:301–309 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gonzalez-Toril E., Llobet-Brossa E., Casamayor E. O., Amann R., Amils R. 2003. Microbial ecology of an extreme acidic environment, the Tinto River. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4853–4865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Good I. J. 1953. The population frequencies of species and the estimation of population parameters. Biometrika 40:237–264 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hammer Ø., Harper D. A. T., Ryan P. D. 2001. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4:1–9 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hansen L. P., Singleton K. J. 1982. Generalized instrumental variables estimation of nonlinear rational expectations models. J. Econom. 50:1269–1286 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hao C., Zhang H., Haas R., Bai Z., Zhang B. 2007. A novel community of acidophiles in an acid mine drainage sediment. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 23:15–21 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heck K. L., Jr, van Belle G., Simberloff D. 1975. Explicit calculation of the rarefaction diversity measurement and the determination of sufficient sample size. Ecology 56:1459–1461 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson D. B. 1998. Biodiversity and ecology of acidophilic microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 27:307–317 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson D. B., Bridge T. A. M. 2002. Reduction of ferric iron by acidophilic heterotrophic bacteria: evidence for constitutive and inducible enzyme systems in Acidiphilium spp. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92:315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson D. B., Hallberg K. B. 2008. Carbon, iron and sulfur metabolism in acidophilic micro-organisms. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 54:201–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaksonen A., et al. 2006. The performance, kinetics and microbiology of sulfidogenic fluidized-bed treatment of acidic metal- and sulfate-containing wastewater. Hydrometallurgy 83:204–213 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kampfer P., et al. 2006. Description of Pseudochrobactrum gen. nov., with the two species Pseudochrobactrum asaccharolyticum sp. nov. and Pseudochrobactrum saccharolyticum sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56:1823–1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kock D., Schippers A. 2008. Quantitative microbial community analysis of three different sulfidic mine tailing dumps generating acid mine drainage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5211–5219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krekeler D., Teske A., Cypionka H. 1998. Strategies of sulfate-reducing bacteria to escape oxygen stress in a cyanobacterial mat. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 25:89–96 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Küsel K., Roth U., Trinkwalter T., Peiffer S. 2001. Effect of pH on the anaerobic microbial cycling of sulfur in mining-impacted freshwater lake sediments. Environ. Exp. Bot. 46:213–223 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leistel J., et al. 1997. The volcanic-hosted massive sulphide deposits of the Iberian Pyrite Belt: review and preface to the thematic issue. Miner. Deposita 33:2–30 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lu S., et al. 2010. Ecophysiology of Fe-cycling bacteria in acidic sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:8174–8183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ludwig W., Strunk O., Westram R., Richter L., Meier H. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maidak B. L., et al. 2001. The RDP-II (Ribosomal Database Project). Nucleic Acids Res. 29:173–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mori K., Kim H., Kakegawa T., Hanada S. 2003. A novel lineage of sulfate-reducing microorganisms: Thermodesulfobiaceae fam. nov., Thermodesulfobium narugense, gen. nov., sp. nov., a new thermophilic isolate from a hot spring. Extremophiles 7:283–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Muyzer G., Ramsing N. B. 1995. Molecular methods to study the organization of microbial communities. Water Sci. Technol. 32:1–9 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nordstrom D. K., Alpers C. N. 1999. Geochemistry of acid mine waters, p. 133–160 The environmental geochemistry of mineral deposits. Part A. Processes, techniques, and health issues. Society of Economic Geologists, Littleton, CO [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nordstrom D. K., Alpers C. N. 1999. Negative pH, efflorescent mineralogy, and consequences for environmental restoration at the Iron Mountain Superfund site, California. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:3455–3462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Otte S., Grobben N. G., Robertson L. A., Jetten M. S., Kuenen J. G. 1996. Nitrous oxide production by Alcaligenes faecalis under transient and dynamic aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2421–2426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rawlings D. E., Tributsch H., Hansford G. S. 1999. Reasons why ‘Leptospirillum’-like species rather than Thiobacillus ferrooxidans are the dominant iron-oxidizing bacteria in many commercial processes for the biooxidation of pyrite and related ores. Microbiology 145:5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rosselló-Mora R., Amann R. 2001. The species concept for prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:39–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rowe O. F., Sánchez-España J., Hallberg K. B., Johnson D. B. 2007. Microbial communities and geochemical dynamics in an extremely acidic, metal-rich stream at an abandoned sulfide mine (Huelva, Spain) underpinned by two functional primary production systems. Environ. Microbiol. 9:1761–1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Runnells D. D., Shepherd T. A., Angino E. E. 1992. Metals in water. Determining natural background concentrations in mineralized areas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 26:2316–2323 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Salkield L. U., Cahalan M. J. 1987. A technical history of the Rio Tinto mines. Some notes on exploitation from pre-Phoenician times to the 1950's. Institution of Mining and Metallurgy, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sanz J. L., Rodriguez N., Díaz E. E., Amils R. 23 May 2011, posting date Methanogenesis in the sediments of Rio Tinto, an extreme acidic river. Environ. Microbiol. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02504.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tan G. L., et al. 2007. Cultivation-dependent and cultivation-independent characterization of the microbial community in acid mine drainage associated with acidic Pb/Zn mine tailings at Lechang, Guangdong, China. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 59:118–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Villemur R., Lanthier M., Beaudet R., Lépine F. 2006. The Desulfitobacterium genus. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30:706–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wauters G., De Baere T., Willems A., Falsen E., Vaneechoutte M. 2003. Description of Comamonas aquatica comb. nov. and Comamonas kerstersii sp. nov. for two subgroups of Comamonas terrigena and emended description of Comamonas terrigena. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:859–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Winch S., Mills H. J., Kostka J. E., Fortin D., Lean D. R. S. 2009. Identification of sulphate-reducing bacteria in methylmercury-contaminated mine tailings by analysis of SSU rRNA genes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 68:94–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yilmaz P., et al. 16 November 2010, posting date The “minimum information about an environmental sequence” (MIENS) specification. Nature Precedings. 10.1038/npre.2010.5252.1 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zettler L. A. A., et al. 2002. Microbiology: eukaryotic diversity in Spain's River of Fire. Nature 417:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.