Abstract

Isolate KH was obtained from Hawaiian forest soil and found to be composed of two functionally linked anaerobes, KHa and KHb. Gene analyses (16S rRNA, fhs, cooS) identified KHa as an acetogenic strain of Clostridium glycolicum and KHb as Bacteroides xylanolyticus. KHb fermented xylan and other saccharides that KHa could not utilize and formed products (e.g., ethanol and H2) that supported the acetogenic growth of KHa.

TEXT

Acetate can be the most abundant organic acid in soil extracts (9, 33). The capacity of aerated soils to form acetate is likely due to transient fermentative activities that can occur when O2 becomes limited and might be dominated by facultative aerobes (e.g., Enterobacteriaceae) (6, 17, 26, 35). However, aerated soils also contain acetogenic bacteria (11, 16, 17, 24, 35), acetate-forming anaerobes that utilize the O2-sensitive acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) Wood-Ljungdahl pathway as a terminal electron-accepting process (7, 8). Although the occurrence of acetogens in aerated soils might be considered paradoxical, certain species of acetogens can cope with small amounts of O2 by (i) reductive processes that remove O2 and its toxic by-products, (ii) utilizing alternative terminal electron-accepting processes that are less sensitive to O2 than is the acetyl-CoA pathway, or (iii) forming symbiotic associations with aerotolerant O2-consuming anaerobes (1, 2, 3, 11, 12, 15, 18, 29). Most acetogens have been isolated from anoxic habitats, such as gastrointestinal tracts or sediments, and relatively few acetogens have been isolated from aerated soils (8). The presence of acetogens in aerated Hawaiian soils has been implicated by the H2-dependent augmentation of acetate formation under anoxic conditions (19), and the main objective of the present study was to isolate an acetogen from Hawaiian forest soil and determine its physiological response to O2.

Analytical procedures.

Gases, organic acids, alcohols, saccharides, pH, and optical densities were measured as described elsewhere (17). The pressures of culture tubes and bottles were determined prior to each gas measurement and taken into consideration for calculating amounts of gases. Gas samples from culture tubes and bottles were analyzed, and the total amount of a gas (e.g., H2) in a tube or bottle was determined by taking into consideration the volume of the gas phase and also the theoretic amount of the gas that was dissolved in the liquid phase (note that the amount of H2 dissolved in the liquid phase was insignificant due to its low solubility). The micromoles of H2 per tube or bottle were converted to millimolar of H2 by taking into account the volume of the liquid phase, thus making it possible to compare the relative (not absolute) concentrations of all products formed from a particular substrate. For example, for a 28-ml culture tube with a 10-ml liquid phase, 50 μmol H2 in the tube would equal 5 mM H2 when weighted against the liquid phase. Concentrations were corrected for the changing liquid-to-volume ratio due to liquid sampling.

fhs (encoding formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase) and 16S rRNA gene sequences were amplified and evaluated according to published protocols (14) with the primers FTHFSf and FTHFSr (21) and 27f and 1492r (20), respectively. fhs sequences of Sporomusa and Moorella were amplified with the newly developed primers fhs610f (GTWGCHTCIGARRTIATGGC) and fhs1249r (CYRCCYTTHGCCCANAC). Sequences of cooS (encodes the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase subunit of acetyl-CoA synthase) were amplified with the newly developed primers cooS805f (AARSCMCARTGTGGTTTTGG) and cooS2623rw (TTTTSTKMCATCCAYTCTGG).

Isolation of KHa and KHb.

For initial enrichment, soil from Koke'e State Park (Kaua'i, HI; for site description, see reference 19) was diluted 1:10 in H2-supplemented yeast extract medium (5) containing vitamins, minerals, and trace metals and lacking reducing agents so as to increase the likelihood of obtaining an acetogen with at least a minimal tolerance to O2. Culture tubes were incubated horizontally at 30°C and were not shaken. The acetogenic culture KH (for Kaua'i, HI) was obtained by streaking enrichments on solidified yeast extract medium (H2-CO2 gas phase), transferring colonies to liquid yeast extract medium, and then restreaking two times. KH was initially thought to be a pure acetogen by its being composed of very similar-looking rods that formed short chains and occasional spores and by its ability to convert numerous substrates primarily to acetate under anoxic conditions. However, KH also formed acetate in response to xylan and raffinose, saccharides that are not normal substrates for known acetogens (8), and it was suspected that KH might contain more than one organism, one being an acetogen and another being a saccharide-utilizing anaerobe that formed products that could be utilized by the acetogen. KHa and KHb were then obtained from the highest growth-positive dilutions of yeast extract medium supplemented with H2 and raffinose, respectively. KHa and KHb were then obtained from isolated colonies on solidified media; they will be made available upon request.

Morphology, physiology, and phylogeny of KHa.

KHa was a spore-forming rod and tended to lyse, thus making it difficult to determine maximum optical densities. Cells were approximately 1.2 μm wide and 4 to 5.2 μm long and often occurred in pairs. The optimum temperature and pH for growth on glucose were 37°C and 8.7, respectively. Growth occurred from 15 to 37°C and pH 5.8 to 9.6 but not at 10°C and 45°C or at pH 5.5 and 9.9. H2-CO2, formate, ethanol, lactate, pyruvate, glucose, xylose, fructose, maltose, citrate, 1-propanol, n-butanol, and yeast extract supported the anaerobic growth of KHa. Under anoxic conditions, acetate was the sole product from H2-CO2 (stoichiometries approximated 4 mol H2 consumed per mol acetate produced) and was the main product with other substrates, with small amounts of butyrate, ethanol, lactate, and H2 also being occasionally formed. Cellulose, xylan, cellobiose, saccharose, raffinose, oxalate, N-acetylglucosamine, galactose, mannose, succinate, butyrate, ethylene glycol, methanol, fumarate, vanillate, ferulate, and CO did not support growth or enhance acetate production above that of control cultures lacking substrate.

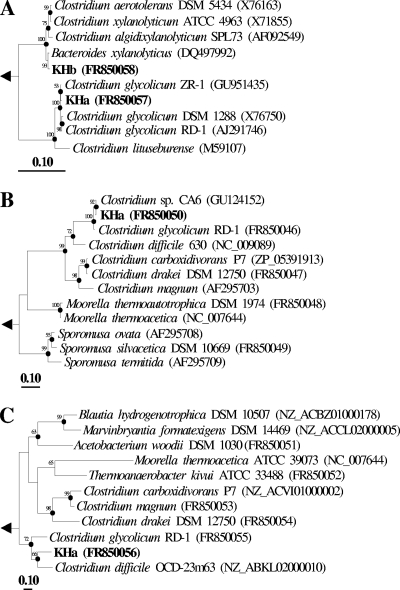

The substrate-product profile as well as the optimal growth conditions of KHa differed from those of fermentative Clostridium glycolicum strains (4, 10) but were similar to those of acetogenic C. glycolicum RD-1 (18). KHa had a 99.1% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity (1,300 bp) to that of the type strain of C. glycolicum, a 97.1% fhs sequence similarity (315 amino acids) to that of C. glycolicum RD-1, and a 72.8% cooS sequence similarity (554 amino acids) to that of C. glycolicum RD-1 (Fig. 1). These combined phenotypic and phylogenetic properties demonstrated that KHa was a new acetogenic strain of C. glycolicum.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenic neighbor-joining trees of 16S rRNA gene sequences of KHa, KHb, and reference sequences (A), in silico-translated amino acid sequences encoded by fhs of KHa and reference sequences (B), and in silico-translated amino acid sequences encoded by cooS of KHa and reference sequences (C). Values next to the branches represent the percentages of replicate trees (>50%) in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 bootstraps). Dots at nodes indicate the confirmation of tree topology by maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony calculations with the same data set. Bar indicates a 0.1 estimated change per nucleic acid or amino acid. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of Methanopyrus kandleri (M59932), the fhs-encoded amino acid sequences of Methanocorpusculum labreanum (CP000559), and the cooS-encoded amino acid sequence of Archaeoglobus fulgidus (NC_000917) were used as outgroups.

KHa grew on glucose in medium containing up to 3% oxygen (O2) in the gas phase (Table 1). Up to 1.5% O2 in the gas phase was consumed. Exposing glucose cultures of KHa to O2 resulted in a shift of the product profile from acetate as the main product without O2 to the enhanced production of lactate and ethanol in response to O2. The acetogen C. glycolicum RD-1 undergoes a similar O2-dependent metabolic shift (18), reinforcing the identification of KHa as an acetogenic strain of C. glycolicum. An increased salt concentration of up to 20 g NaCl liter−1 also resulted in an increased production of ethanol (up to 1.6 mM) from 5 mM fructose. The capacity to produce ethanol is a property of other clostridial acetogens (e.g., Clostridium carboxidivorans, Clostridium ljungdahlii, and “Clostridium ragsdalei” [quotation marks indicate that the organism has not been validated]) (22, 25, 27, 34).

Table 1.

Effect of O2 on the glucose-dependent product profile of KHaa

| % of initial O2 | Amt of glucose consumed (mM) | Max OD660 | Amt of product (mM) |

% recovery |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Ethanol | Lactate | Butyrate | H2 | Carbon | Reductant | |||

| 0 | 4.6 | 0.45 | 13.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 99 | 100 |

| 0.5 | 5.4 | 0.52 | 13.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 86 | 87 |

| 1.0 | 5.9 | 0.35 | 11.4 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 71 | 72 |

| 2.0 | 5.0 | 0.42 | 12.2 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 91 | 94 |

| 3.0 | 4.5 | 0.46 | 6.8 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 80 | 85 |

| 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA |

The medium was yeast extract medium lacking reducing agents (5) supplemented with approximately 5 mM glucose. Values were corrected with values from control cultures lacking glucose and O2 (i.e., 2.4 mM acetate and 0.1 mM H2). Values are means from two replicates. No products and no growth were detected with higher concentrations of O2. NA, not applicable.

Morphology, physiology, and phylogeny of KHb.

KHb was a non-spore-forming rod. As with KHa, KHb tended to lyse, thus making it difficult to determine maximum optical densities. Cells were approximately 1.0 μm wide and 2.6 to 3.2 μm long and often occurred in pairs or short chains. The optimum temperature and pH for growth on glucose were 37°C and 6.9, respectively. Growth occurred from 15 to 37°C and pH 5.5 to 8.2 but not at 10°C and 45°C or at pH 5.1 and 8.7. Xylan (provided as a suspension prepared from autoclaved powder, a suspension prepared from UV-irradiated powder, or an autoclaved suspension, all of which yielded similar product profiles), raffinose, cellobiose, saccharose, maltose, galactose, glucose, xylose, mannose, N-acetylglucosamine, citrate, fumarate, pyruvate, ethylene glycol, and yeast extract supported the growth of KHb, as determined by an increase in optical density or the production of products above control cultures lacking substrate. Acetate, ethanol, lactate, formate, and H2 were formed as end products (Table 2). Although CO2 was not determined, it is likely that CO2 was also produced by KHb, a matter that would partly explain the relatively low recovery of carbon (Table 2). Cellulose, ethanol, 1-propanol, n-butanol, oxalate, lactate, succinate, butyrate, methanol, vanillate, ferulate, and CO did not support growth.

Table 2.

Effect of O2 on the glucose-dependent product profile of KHba

| % of initial O2 | Amt of glucose consumed (mM) | Max OD660 | Amt of product (mM)b |

% recovery |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Ethanol | Lactate | Formate | H2 | Carbon | Reductant | |||

| 0 | 5.2 | 0.53 | 2.6 | 5.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 6.6 | 55 | 82 |

| 0.5 | 4.9 | 0.56 | 3.2 | 6.6 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 5.1 | 70 | 100 |

| 1 | 5.0 | 0.50 | 3.3 | 6.7 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 3.7 | 72 | 99 |

| 2 | 4.9 | 0.52 | 3.8 | 8.4 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 2.3 | 90 | 121 |

| 3 | 3.9 | 0.51 | 3.6 | 5.3 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 86 | 110 |

| 4 | 4.6 | 0.39 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 75 | 93 |

| 5 | 5.1 | 0.49 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 83 | 101 |

| 6c | 5.1 | 0.47 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 71 | 86 |

| 10 | 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA |

The medium was yeast extract medium lacking reducing agents (5) supplemented with approximately 5 mM glucose. Values were corrected with values from control cultures lacking glucose and O2 (0.4 mM acetate, 0.3 mM formate, 0.6 mM H2). Values are means from two replicates. NA, not applicable.

It is likely that KHb also produced CO2.

Growth and activity were observed with only one of the two replicates. Thus, the values for this cultivation condition are from the single growth-positive culture.

The morphology and substrate-product profile of KHb were very similar to those of the type strain of Bacteroides xylanolyticus (28). KHb had a 99.4% 16S rRNA gene sequence (1,336 bp) similarity to that of the type strain of B. xylanolyticus (Fig. 1). No PCR signal was obtained for fhs and cooS with KHb. These combined phenotypic and genotypic properties demonstrated that KHb was a new strain of fermentative anaerobe B. xylanolyticus. KHb grew on glucose in medium containing up to 6% O2 in the gas phase (Table 2). Up to 4% O2 in the gas phase was consumed. Exposure to O2 resulted in a modest alteration of the product profile of KHb, with lactate and formate increasing and ethanol and H2 decreasing in response to large amounts of O2. The capacity of KHb to utilize diverse saccharides and the moderate aerotolerance of KHb are properties consistent with those of other Bacteroides species (13, 23, 30–32).

Trophic interaction of C. glycolicum KHa and B. xylanolyticus KHb.

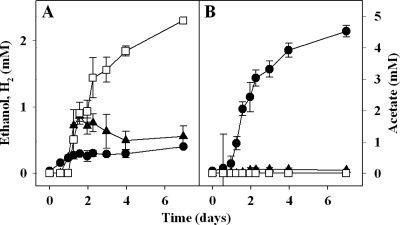

KHb fermented substrates that were not used by KHa and formed products that supported the growth of KHa. For example, raffinose, a trisaccharide, was not utilized by KHa but was growth supportive for KHb, yielding large amounts of ethanol and H2 (Table 3). In contrast, cocultures of KHa and KHb converted raffinose to acetate (Table 3). This trophic interaction also occurred with cocultures of KHa and KHb on xylan. As noted above, KHa did not utilize xylan. Xylan cultures of KHb produced ethanol, H2, and acetate (Fig. 2 A). Cocultures of KHa and KHb on xylan yielded primarily acetate, with ethanol and H2 being minimal (Fig. 2B). The apparent capacity of cocultures to convert xylan to acetate is noteworthy, given the commercial interest in using acetogens to convert plant biomass to useful chemicals (ZeaChem, Inc.).

Table 3.

Raffinose-dependent product profiles of KHa, KHb, and cocultures of KHa and KHba

| Organism | Substrate consumed (mM) | Max OD660 | Amt of product (mM)b |

% recovery |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Ethanol | H2 | Carbon | Reductant | |||

| KHa | Raffinose (0) | 0.15c | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA |

| KHb | Raffinose (1.7) | 0.60 | 3.1 | 9.4 | 5.8 | 82 | 122 |

| KHa/KHb | Raffinose (1.7) | 0.81 | 14.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 93 | 93 |

The medium was yeast extract medium lacking reducing agents (5) supplemented with approximately 1.7 mM raffinose. Values were corrected with values from control cultures lacking raffinose (for KHa: 4 mM acetate, 1 mM butyrate; for KHb: 0.8 mM acetate, 0.6 mM H2). Values are means from two replicates. NA, not applicable.

It is likely that KHb also produced CO2.

The OD660 was due to growth on yeast extract.

Fig. 2.

Xylan-dependent product profiles of KHb (A) and cocultures of KHa and KHb (B). Values were corrected with values obtained from control cultures (i.e., KHb for panel A and cocultures of KHa and KHb for panel B) lacking xylan. Medium was yeast extract medium (5). Xylan was provided at a final concentration of approximately 0.1% (wt/vol); the xylan stock solution was a sterile anoxic suspension prepared from autoclaved xylan powder. Error bars show the variance of triplicate cultures; symbols are placed at mean values (the error bar is smaller than the size of the symbol where no bar is apparent). Symbols: filled circles, acetate; empty squares, ethanol; filled triangles, H2.

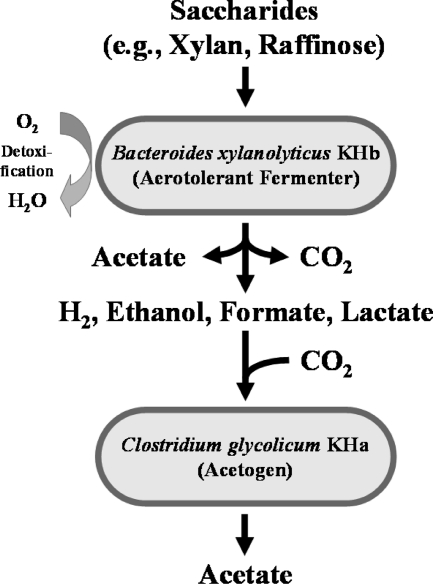

These collective results suggested that products of KHb (e.g., ethanol and H2) were converted to acetate by KHa in cocultures of KHa and KHb (Fig. 3). The production of lactate, formate, and H2 by an aerotolerant fermentative bacterium and subsequent utilization by an acetogen have been observed with two other commensal cocultures, namely, Thermicanus aegyptius and Moorella thermoacetica (11) and Clostridium intestinale and Sporomusa rhizae (12). In the present study, ethanol was also found to be a functional link between an aerotolerant fermenter (B. xylanolyticus KHb) and an acetogen (C. glycolicum KHa) (Fig. 3). This proposed interaction does not preclude the capacity of KHa to consume monosaccharides released during the hydrolysis of polysaccharides by KHb.

Fig. 3.

Hypothetical model for the trophic interaction of Bacteroides xylanolyticus KHb and Clostridium glycolicum KHa.

Acetogens are classically considered to be obligate anaerobes (7). KHa tolerated minimal amounts of O2 (Table 1), a characteristic shared with other acetogens (e.g., Sporomusa silvacetica, C. glycolicum RD-1) (2, 3, 12, 15, 18). However, the fermentative partner KHb tolerated and consumed larger amounts of O2 than did the acetogen KHa (Tables 1 and 2), a pattern also observed with the aforementioned commensal partnerships (11, 12). As with the parent culture KH, the aforementioned partnerships were also initially isolated as a presumably pure culture that was subsequently found to be composed of two functionally linked bacteria. Although the isolation of an acetogen together with an aerotolerant fermenter might be considered a laboratory phenomenon, the accidental isolation of three such partnerships illustrates a type of interaction that might occur in situ between so-called obligate anaerobes and aerotolerant fermentative organisms. In the case of acetogens in habitats subject to large fluctuations of O2 (e.g., soil), it would seem beneficial to be associated with O2-consuming aerotolerant fermentative organisms that convert nonacetogenic substrates to products that can subsequently support acetogenic growth.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Nucleotide sequences are available from the EMBL nucleotide sequence database under accession numbers FR850046 to FR850058.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study was provided by the University of Bayreuth.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Balk M., van Gelder T., Weelink S. A., Stams A. J. M. 2008. (Per)chlorate reduction by the thermophilic bacterium Moorella perchloratireducens sp. nov., isolated from underground gas storage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:403–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boga H., Brune A. 2003. Hydrogen-dependent oxygen reduction by homoacetogenic bacteria isolated from termite guts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:779–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boga H. I., Ludwig W., Brune A. 2003. Sporomusa aerivorans sp. nov., an oxygen-reducing homoacetogenic bacterium from a soil-feeding termite. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1397–1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chamkha M., Labat M., Patel B. K. C., Garcia J.-L. 2001. Isolation of a cinnamic acid-metabolizing Clostridium glycolicum strain from oil mill wastewaters and emendation of the species description. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:2049–2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daniel S. L., Hsu T., Dean S. I., Drake H. L. 1990. Characterization of the H2- and CO-dependent chemolithotrophic potentials of the acetogens Clostridium thermoaceticum and Acetogenium kivui. J. Bacteriol. 172:4464–4471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Degelmann D. M., Kolb S., Dumont M., Murrell J. C., Drake H. L. 2009. Enterobacteriaceae facilitate the anaerobic degradation of glucose by a forest soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 68:312–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drake H. L., Gößner A. S., Daniel S. L. 2008. Old acetogens, new light, p. 100–128 In Wiegel J., Maier R. J., Adams M. W. W. (ed.), Incredible anaerobes: from physiology to genomics to fuels, vol. 1125 New York Academy of Science, New York, NY: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drake H. L., Küsel K., Matthies C. 2006. Acetogenic prokaryotes, p. 354–420 In Dworkin M., Falkow S., Rosenberg E., Schleifer K.-H., Stackebrandt E. (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed., vol. 2 Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fox T. R., Comerford N. B. 1990. Low-molecular-weight organic acids in selected forest soils of the southeastern U. S. A. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 54:1139–1144 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gaston L. W., Stadtman E. R. 1963. Fermentation of ethylene glycol by Clostridium glycolicum, sp. n. J. Bacteriol. 85:356–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gößner A. S., et al. 1999. Thermicanus aegyptius gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from oxic soil, a fermentative microaerophile that grows commensally with the thermophilic acetogen Moorella thermoacetica. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:5124–5133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gößner A. S., et al. 2006. Trophic interactions of the aerotolerant anaerobe Clostridium intestinale and the acetogen Sporomusa rhizae sp. nov. isolated from roots of the black needlerush Juncus roemerianus. Microbiology 152:1209–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gregory E. M., Fanning D. D. 1983. Effect of heme on Bacteroides distasonis catalase and aerotolerance. J. Bacteriol. 156:1012–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hunger S., et al. 2011. Competing formate- and carbon dioxide-utilizing prokaryotes in an anoxic methane-emitting fen soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:3773–3785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karnholz A., Küsel K., Gößner A. S., Schramm A., Drake H. L. 2002. Tolerance and metabolic response of acetogenic bacteria toward oxygen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1005–1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuhner C. H., et al. 1997. Sporomusa silvacetica sp. nov., an acetogenic bacterium isolated from aggregated forest soil. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:352–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Küsel K., Drake H. L. 1995. Effect of environmental parameters on the formation and turnover of acetate in forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3667–3675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Küsel K., et al. 2001. Physiological ecology of Clostridium glycolicum RD-1, an aerotolerant acetogen isolated from sea grass roots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4734–4741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Küsel K., et al. 2002. Microbial reduction of Fe(III) and turnover of acetate in Hawaiian soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 40:73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lane D. J. 1991. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing, p. 115–175 In Stackebrandt E., Goodfellow M. (ed.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. John Wiley and Sons Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leaphart A. B., Lovell C. R. 2001. Recovery and analysis of formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase gene sequences from natural populations of acetogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1392–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liou J. S.-C., Balkwill D. L., Drake G. R., Tanner R. S. 2005. Clostridium carboxidivorans sp. nov., a solvent-producing clostridium isolated from an agricultural settling lagoon, and reclassification of the acetogen Clostridium scatologenes strain SL1 as Clostridium drakei sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55:2085–2091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pan N., Imlay J. A. 2001. How does oxygen inhibit central metabolism in the obligate anaerobe Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron? Mol. Microbiol. 39:1562–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peters V., Conrad R. 1995. Methanogenic and other strictly anaerobic bacteria in desert soil and other oxic soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1673–1676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Phillips J. R., Clausen E. C., Gaddy J. L. 1994. Synthesis gas as substrate for the biological production of fuels and chemicals. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 46:145–157 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reith K., Drake H. L., Küsel K. 2002. Anaerobic activities of bacteria and fungi in moderately acidic conifer and deciduous leaf litter. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 41:27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saxena J., Tanner R. S. 2011. Effect of trace metals on ethanol production from synthesis gas by the ethanologenic acetogen, Clostridium ragsdalei. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 38:513–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scholten-Koerselman I., Houwaard F., Janssen P., Zehnder A. J. B. 1986. Bacteroides xylanolyticus sp. nov., a xylanolytic bacterium from methane producing cattle manure. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 52:543–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Silaghi-Dumitrescu R., et al. 2003. A flavodiiron protein and high molecular weight rubredoxin from Moorella thermoacetica with nitric oxide reductase activity. Biochemistry 42:2806–2815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith C. J., Rocha E. R., Paster B. J. 2006. The medically important Bacteroides spp. in health and disease, p. 381–427 In Dworkin M., Falkow S., Rosenberg E., Schleifer K.-H., Stackebrandt E. (ed.), The prokaryotes, 3rd ed., vol. 7 Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tally F. P., Steward P. R., Sutter V. L., Rosenblatt J. E. 1975. Oxygen tolerance of fresh clinical anaerobic bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1:161–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tang Y. P., Dallas M. M., Malamy M. H. 1999. Characterization of the BatI (Bacteroides aerotolerance) operon in Bacteroides fragilis: isolation of a B. fragilis mutant with reduced aerotolerance and impaired growth in in vivo model systems. Mol. Microbiol. 32:139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tani M., Higashi T., Nagatsuka S. 1993. Dynamics of low-molecular-weight aliphatic carboxylic acids (LACAs) in forest soils. I. Amount and composition of LACAs in different types of forest soils in Japan. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 39:485–495 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tanner R. S., Miller L. M., Yang D. 1993. Clostridium ljungdahlii sp. nov., and acetogenic species in clostridial rRNA homology group I. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:232–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wagner C., Grießhammer A., Drake H. L. 1996. Acetogenic capacities and the anaerobic turnover of carbon in a Kansas prairie soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:494–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]