Abstract

Members of the LEF-1/TCF family of transcription factors have been implicated in the transduction of Wnt signals. However, targeted gene inactivations of Lef1, Tcf1, or Tcf4 in the mouse do not produce phenotypes that mimic any known Wnt mutation. Here we show that null mutations in both Lef1 and Tcf1, which are expressed in an overlapping pattern in the early mouse embryo, cause a severe defect in the differentiation of paraxial mesoderm and lead to the formation of additional neural tubes, phenotypes identical to those reported for Wnt3a-deficient mice. In addition, Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos have defects in the formation of the placenta and in the development of limb buds, which fail both to express Fgf8 and to form an apical ectodermal ridge. Together, these data provide evidence for a redundant role of LEF-1 and TCF-1 in Wnt signaling during mouse development.

Keywords: LEF-1, TCF-1, Wnt, limb development, mesoderm differentiation

Signaling by Wnt/wg proteins is involved in the regulation of cell fate decisions and cell proliferation (for review, see Cadigan and Nusse 1997; Moon et al. 1997). Members of the LEF-1/TCF family of transcription factors can interact with β-catenin, a downstream component of the Wnt signaling pathway, and activate transcription. To date, four members of this family have been identified in mammals; lymphoid enhancer factor-1 (LEF-1), T cell factor -1 (TCF-1), TCF-3 and TCF-4 (Travis et al. 1991; Waterman et al. 1991; van de Wetering et al. 1991; Korinek et al. 1998a). All four proteins have a virtually identical DNA-binding domain and β-catenin interaction domain. These transcription factors can augment gene expression in association with β-catenin and in response to Wnt-1 signaling in tissue culture transfection assays (van de Wetering et al. 1997; Hsu et al. 1998; Korinek et al. 1998a). In addition, LEF–1/TCF proteins can associate with the proteins CBP and Groucho, which confer repression in the absence of a Wnt/wg signal (Cavallo et al. 1998; Levanon et al. 1998; Roose et al. 1998; Waltzer and Bienz 1998). Finally, LEF-1 can interact with the protein ALY and functions as an architectural component in the assembly of a multiprotein enhancer complex (Bruhn et al. 1997).

Consistent with the presumed role of these transcription factors in Wnt/wg signaling, mutations in a Drosophila ortholog of Lef1 generate a wingless (wg) phenotype (Brunner et al. 1997; van de Wetering et al. 1997). However, the role of the mammalian transcription factors in signaling by Wnt proteins in vivo has been obscure because mutations of the Lef1, Tcf1, or Tcf4 genes did not generate any phenotype that resembles known Wnt mutations. Lef1−/− mice show a block in the development of teeth, hair follicles, and mammary glands , a null mutation in Tcf1 results in an incomplete arrest in T lymphocyte differentiation and Tcf4−/− mice have a defect in the development of the small intestine (Korinek et al. 1998b). In contrast, null mutations in the Wnt3a and Wnt4 genes, which are expressed in the early mouse embryo in regions that also express Lef1 and Tcf1, result in defects in the formation of paraxial mesoderm, and kidneys, respectively (Stark et al. 1994; Takada et al. 1994). The partial overlap in the expression of Lef1 and Tcf1 in mouse development (Oosterwegel et al. 1993), therefore, raises the question as to whether genetic redundancy can account for the lack of a Wnt-like phenotype in mice carrying targeted mutations in either transcription factor gene.

Results

Redundancy of the expression and function of Lef1 and Tcf1 in the early mouse embryo

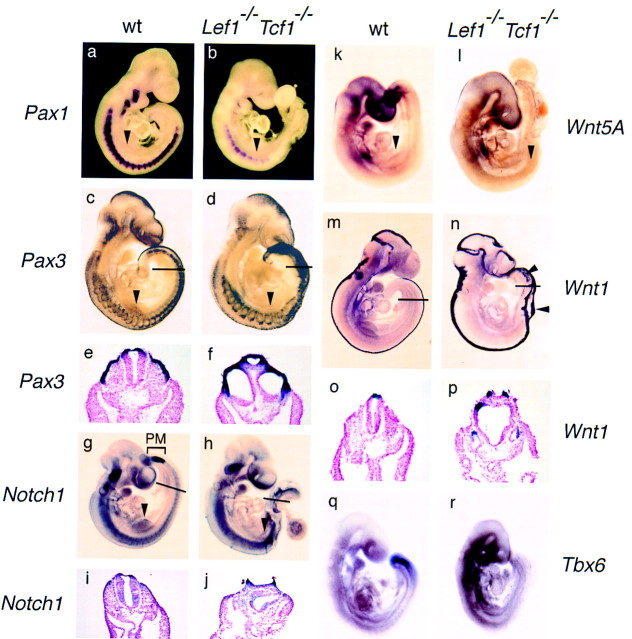

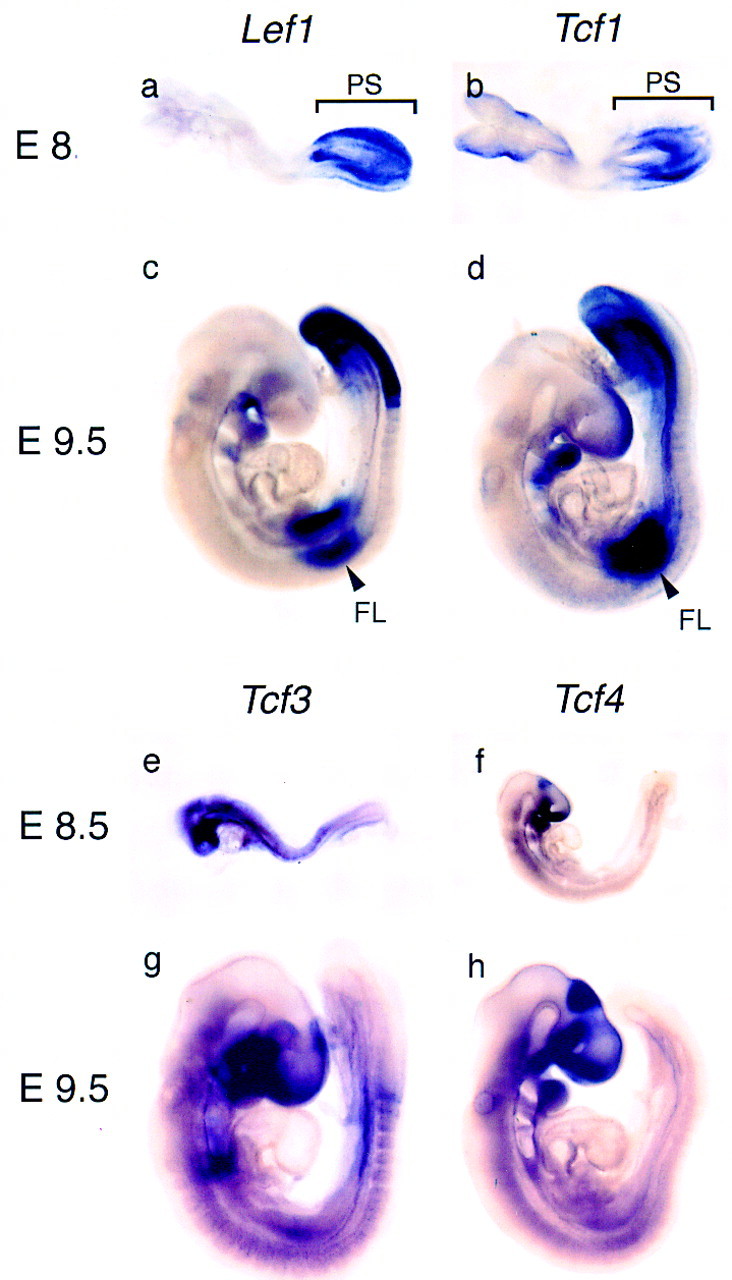

To compare in more detail the expression pattern of individual Lef1/Tcf genes in early mouse development, we performed whole mount in situ hybridization with probes specific for the four known members of this gene family (Fig. 1). Lef1 and Tcf1 are both expressed abundantly in the primitive streak of E8.5 embryos, whereas Tcf3 and Tcf4 are expressed predominantly in the primordia of the fore- and midbrain. In E8.5 embryos, expression of Tcf3 can also be detected in the primordia of the hindbrain and in the forming somites. In E9.5 embryos, additional overlapping Lef1 and Tcf1 expression is detected in the forelimbs and branchial arches, consistent with a previous in situ hybridization analysis of sections of embryos (Oosterwegel et al. 1993). Thus, Lef1 and Tcf1, but not the other members of the gene family are expressed in an overlapping pattern in the primitive streak and in limb buds.

Figure 1.

Expression of members of the LEF-1/TCF family of transcription factors in early mouse development. Expression was analyzed at embryonic day 8.5 (E8.5) and E9.5 by whole mount in situ hybridization with cDNA probes for Lef1 (a,c), Tcf1 (b,d), Tcf3 (e,g), and Tcf4 (f,h). In E8.5 embryos, expression of Lef1 and Tcf1 is detected predominantly in the primitive streak (PS) and in E9.5 embryos expression is detected in the primitive streak and unsegmented presomitic mesoderm, the forelimb bud (FL) and the branchial arches. Tcf3 expression is detected in newly formed somites and in the primordia of the fore-, mid-, and hindbrain. Expression of Tcf4 at E9.0 (f) is detected in the midbrain, around the optic placode, in the P2 region of the diencephalon, and the forming hindgut.

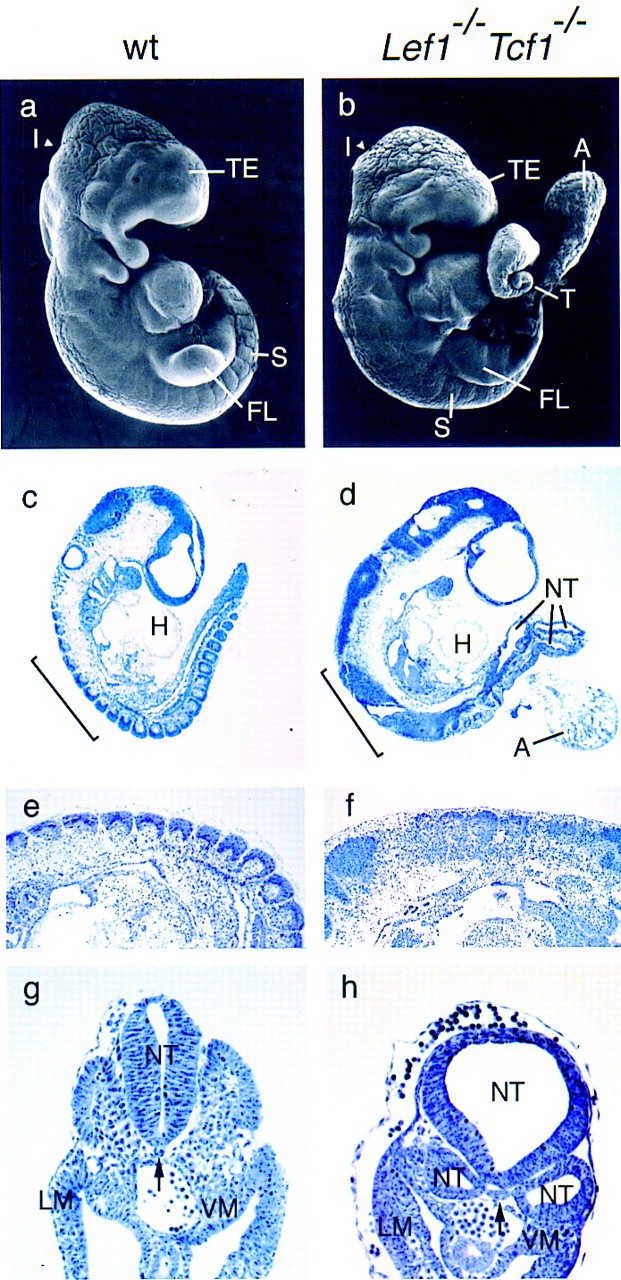

We examined a potential redundancy between LEF-1 and TCF-1 by generating compound homozygous mice carrying null alleles of both genes. Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos were recovered at the expected frequency between E6.5 and 9.5, but their frequency was markedly reduced after E10.5. Scanning electron microscopy of E9.5 embryos revealed caudal and limb bud defects in the compound mutant homozygotes (Fig. 2a,b). In addition, the allantois of the mutant embryos forms an abnormal mass of cells, which may be related to the lack of a placenta in E10.5 mutant animals (data not shown). The telencephalic vesicle of the mutant embryos is also smaller than that of wild-type embryos. Histological analysis of E9.5 Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos confirmed the caudal defects and revealed a severe deficiency in the formation of somites (Fig. 2d). Anterior to the level of the forelimb bud, somites of abnormal morphology were detected (Fig. 2f), whereas no somites were found in the caudal region, which is highly deformed and contains multiple tube-like structures (Fig. 2d). Transverse sections in the caudal region confirmed the lack of somites and revealed multiple (up to five) tubular structures in the mutant embryos (Fig. 2h). This phenotype indicates a deficiency in the formation of presomitic (paraxial) mesoderm. Mesoderm is first formed during gastrulation when cells delaminate from the epiblast into the primitive streak at the posterior region of the embryo. Within the primitive streak, spatially defined precursors generate different mesodermal fates, such as axial, paraxial, intermediate, and lateral mesoderm (Tam and Beddington 1987, 1992). The mutant embryos contain both lateral and visceral mesoderm (Fig. 2h) and have a heart, a dorsolateral mesoderm derivative (Fig. 2d), suggesting that the absence of LEF-1 and TCF-1 affects the differentiation of specific mesodermal cell types.

Figure 2.

Caudal defects in embryos carrying targeted null mutations in both Lef1 and Tcf1 genes. (a,b) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of E9.5 wild-type (a) and Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− (b) littermates. In the mutant embryo, somites can be detected up to the forelimb (FL), but not in the caudal region. The caudal extremity of the tail (T) shows an abnormal morphology, is deformed and comparably smaller than the wild type. The mutant embryo also has a smaller telencephalic vesicle (TE) and a less pronounced isthmus (I) between midbrain and the hindbrain. The mass of cells labeled A corresponds to the remnants of the allantois, which is not fused to the placenta (data not shown). Histology of sagital sections of E9.5 wild-type (wt; c,e) and Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− (d,f) embryos. Somites and a well-developed heart (H) can be seen in the wild-type embryo. In the mutant embryo, no identifiable somites can be detected in the disformed caudal half of the embryo, which contains multiple neural tube-like structures (NT). The mutant embryo has, however, a heart (d). In the region anterior to the forelimb level (bracket in c,d) somites can be detected in both wild-type and mutant embryos (e,f). However, somites in the mutant embryo have incomplete structure and lack clear segmental boundaries. (g,h) Transverse sections of E9.5 wild-type and mutant embryos at a caudal level at which normally the first somites form. In the mutant embryo (h) three neural tubes are detected. Normal lateral mesoderm (LM) and visceral mesoderm (VM) are formed in the mutant embryo. (Arrow) Position of the notochord. (a–f) Rostral is to the left and caudal to the right.

Defects in paraxial mesoderm differentiation in Lef1−/− Tcf1−/− embryos

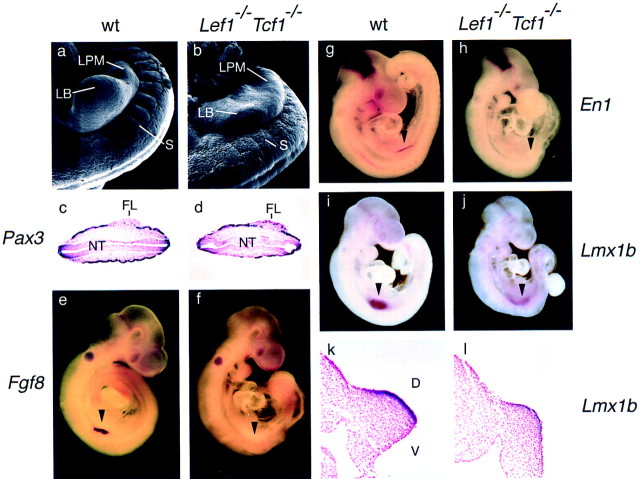

To further define the mesodermal defects in the double mutant embryos, we performed whole-mount in situ hybridization with several probes that identify specific mesodermal cell populations (Fig. 3). Expression of the sclerotome marker, Pax1, was detected in the seven to nine somites anterior of the forelimb buds, albeit at a reduced level (Fig. 3b). No Pax1 expression was found in the region posterior to the forelimb buds, consistent with the lack of caudal somites. Pax3 transcripts, which are normally found in the presomitic paraxial mesoderm, dermamyotome and dorsal neural tube, are detected in the dermamyotomes anterior to the forelimb level and in broad bands in the caudal region (Fig. 3d). Transverse sections showed that the hybridization pattern of Pax3 in the caudal region represents the dorsal half of multiple tubes rather than dermamyotomes (Fig. 3f). Moreover, the mutant embryos failed to express Notch1 in the area of presomitic mesoderm formation (Fig. 3h), although expression was detected in the neural tube (Fig. 3j). We also examined expression of Wnt5a, which is normally expressed in the tail bud region that forms paraxial mesoderm (Tam and Beddington 1987, 1992; Takada et al. 1994). No Wnt5a expression was detected in the tail bud region of Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos (Fig. 3l). To examine the identity of the tubular structures in the caudal region of Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos, we analyzed the expression of Wnt1 as a marker for dorsal CNS (Parr et al. 1993; Takada et al. 1994). In mutant embryos, Wnt1 expression was generally increased in the CNS and was also found in multiple stripes and clusters of cells in the caudal region (Fig. 3n). Moreover, transverse sections in the caudal region of the mutant embryo showed that the dorsal part of each of the tubular structures contains Wnt1-expressing cells (Fig. 3p). Thus, Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos appear to lack paraxial mesoderm posterior to the forelimb level and they form ectopic neural tubes, phenotypes that are virtually identical to those reported for Wnt3a−/− mice (Takada et al. 1994; Yoshikawa et al. 1997).

Figure 3.

Expression of mesoderm and neural markers in wild-type and Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos. Analysis of molecular markers by whole-mount in situ hybridization on E9.5 embryos. The sclerotome marker, Pax1, shows a regular pattern of somitic expression throughout the wild-type embryo, whereas weak expression is detected only in nine somites anterior to the forelimb level (arrowhead) in the mutant embryo (a,b). Pax3, normally expressed in the dorsal neural tube and the dermamyotome is expressed in the mutant embryo in a nonsegmental pattern caudal to the forelimb level (arrowhead; c,d). Transverse sections of the caudal region of these embryos (thin line) are shown in e and f. Pax3 expression is detected in the dermamyotome and in the dorsal neural tube of a wild-type embryo and in three neural tubes of the mutant embryo. Expression of Notch1 in the unsegmented presomitic mesoderm (PM; bracket) is observed in wild-type but not in mutant embryos (g,h). Notch1 expression is also detected in the forelimb bud of the wild-type embryo (arrowhead in g), but it is absent in the forelimb bud of the mutant embryo (arrowhead; h). Expression of Notch1 in the neural tube is detected in transverse sections of both wild-type and mutant embryos (i,j). In the mutant embryo, one of the neural tubes is not closed. Expression of Wnt5a in the presomitic mesoderm is detected in the wild-type embryo (k) but not in the mutant embryo(l). Expression of Wnt5a is also detected in the forelimb bud (arrowhead) of the wild-type, but not mutant embryo. (m–p) Pattern of expression of the dorsal CNS marker, Wnt1, in whole-mount hybridization and in transverse sections of the caudal region at the level indicated by a thin line. Wnt1 is expressed in the brain of wild-type and mutant embryos at a similar level, but expression is increased in the CNS of the mutant embryo. In the region posterior to the forelimb level of the mutant embryo, additional signals can be detected in extra bands and patches of cells (arrowheads; n) that represent an open neural tube and three additional neural tubes (p). The presomitic mesoderm marker, Tbx6, is expressed in the tailbud and presomitic mesoderm of the wild-type, but not mutant embryo (q,r).

The formation of additional neural tubes, however, is also observed in mouse mutant Fgfr1−/− chimeras and in embryos carrying mutations in the Tbx6 gene (Deng et al. 1997; Chapman and Popaioannou 1998). In particular, the targeted mutation of the T-box transcription factor gene, Tbx6, which is related to Brachyury, also causes paraxial mesoderm defects similar to those observed in Wnt3a−/− and Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos (Chapman et al. 1996; Chapman and Papaioannou 1998). Therefore, we examined the expression of Tbx6 and detected no expression in the caudal region of the Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos (Fig. 3r). This absence of detectable Tbx6 expression in the tail bud region of the compound homozygous mutant embryos suggests that either the cells that normally express Tbx6 are missing, and/or alternatively, that LEF-1/TCF-1 and Wnt signaling may act upstream of Tbx6. Because expression of Tbx6 in E9.5 embryos requires Brachyury (Chapman et al. 1996), which we have identified as a direct target for LEF-1/TCF proteins (J. Galceron, S.C. Hsu, and R. Grosschedl, unpubl.), we favor the view that LEF-1/TCF proteins act upstream of Tbx6.

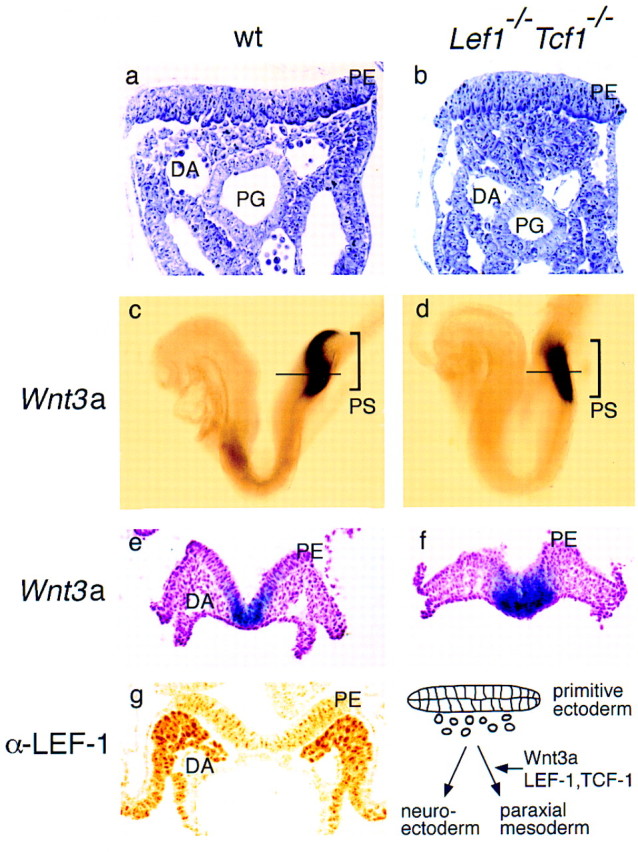

To address the issue of whether the ectopic neural tubes are formed at the expense of paraxial mesoderm, as seen in Wnt3a−/− mice (Yoshikawa et al. 1997), we examined wild-type and Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos at E8.5, a stage at which cells ingress through the primitive streak (Tam and Beddington 1987). In transverse sections of the primitive streak region, mesodermal cells of mesenchymal morphology were detected under the ectoderm layer in wild-type embryos, whereas only densely packed cells of epithelial morphology and tubular arrangement were found in mutant embryos (Fig. 4a,b). We also examined whether proliferation and apoptosis is altered in the caudal region of the Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos by counting the numbers of dividing and apoptotic cells. No significant differences were detected between wild-type and mutant embryos (data not shown). Therefore, the ectopic neural tubes appear to be formed at the expense of paraxial mesoderm. The generation of cells underlying the primitive ectoderm suggests that the Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− mutant mice have no obvious defect in the delamination of epithelial cells, which is impaired in Fgfr1−/− mutant mice (Deng et al. 1997). Thus, the defect in Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos might occur at a subsequent differentiation step.

Figure 4.

Ectopic formation of neural tissue in Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos at the expense of paraxial mesoderm. (a,b) Histological analysis of the primitive streak region in wild-type and mutant E8.5 embryos. The cells underlying the primitive ectoderm (PE) have mesenchymal morphology in the wild-type embryos (a) and compact epithelial morphology in the mutant embryo (b). The positions of the dorsal aorta (DA) and primitive gut (PG) are shown. (c–f). Expression of Wnt3a in the primitive streak (PS) region of E8.0 wild-type (c) and mutant embryos (d). In transverse sections at a level indicated by a horizontal line, Wnt3a expression can be detected in the primitive ectoderm (PE) and in the epithelial cell mass underlying the primitive ectoderm of the mutant embryo (d). (g) Expression of Lef1 in the presomitic mesoderm. Detection of LEF-1 protein by immunohistochemistry with a polyclonal anti-LEF-1 serum in a transverse section of an E8.5 wildtype embryo in the primitive streak region. Schematic diagram of the fate of cells delaminating from the primitive ectoderm in the absence or presence of Wnt3a, and LEF-1 and TCF-1.

The striking similarity of the paraxial mesoderm defect in Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− mice and Wnt3a−/− mice raised the question of whether these genes are connected in a feedback loop. We examined the expression of Wnt3a in E 8.5 embryos and detected similar expression in the posterior region of wild-type and Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos, consistent with a function of LEF-1 and TCF-1 downstream of Wnt3a. In transverse sections, Wnt3a expression was detected only in the primitive ectoderm of wild-type embryos, whereas it was also found in the underlying ectopic neural tissue of the mutant embryo (Fig. 4e,f). Although the area of expression is expanded in the compound mutant embryos as compared with wild-type embryos, we favor the view that the expanded expression is due to the generation of excess neural ectoderm at the expense of mesoderm, rather than a loss of negative regulation, which has been shown to operate in the absence of Wnt signals (Cavallo et al. 1998; Waltzer and Bienz 1998). Finally, we examined which cells in the primitive streak contain LEF-1 protein. By immunohistochemistry of E9.5 embryos with anti LEF-1 antibodies, we detected abundant LEF-1 protein in the presomitic mesoderm and in the somites, but not in the primitive ectoderm (Fig. 4g). This expression pattern is consistent with a model for paraxial mesoderm differentiation in which cells that migrate through the primitive streak upregulate the expression of LEF-1 and become competent for a Wnt3a signal from the ectodermal cells to assume a mesodermal rather than neuroectodermal cell fate.

Arrest of limb development in Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos

Lef1 and Tcf1 are also expressed in an overlapping pattern in the forelimb bud of E9.5 embryos. The early limb bud protrudes from the lateral body wall and is comprised of lateral plate mesoderm and ectoderm. As the limb bud develops, three distinct signaling centers are formed that are required for proper outgrowth and patterning of a limb (Johnson and Tabin 1997; Martin 1998). The apical ectodermal ridge (AER) is a specialized epithelial structure that is located at the distal margin of the bud. In the mouse, the AER expresses at least four Wnt genes (Wnt3, Wnt4, Wnt6, and Wnt7b) and four fibroblast growth factor (Fgf) genes, (Fgf2, Fgf4, Fgf8, Fgf9) (for review, see Martin 1998). In the underlying distal mesoderm, which includes the progress zone and contains precursors of the limb mesenchymal cells, slug, Fgf10, and Msx1 are expressed. Msx1 transcripts are also found along the entire anterior and posterior margins (Ros et al. 1992). The zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) is defined by expression of sonic hedgehog at the posterior margin of the bud (for review, see Johnson and Tabin 1997; Martin 1998). In addition, the dorsal ectoderm of the limb bud is known to produce signals that regulate the dorsal–ventral (D–V) axis and is characterized by the expression of Wnt7a (Parr et al. 1993; Parr and MacMahon 1995). Wnt5a is expressed in both the ventral limb ectoderm and in a graded manner in the limb mesenchyme (Parr et al. 1993). Lef1 expression is found in the mesenchyme of the limb bud but not in the AER, whereas Tcf1 is expressed in both mesenchyme and AER (Oosterwegel et al. 1993).

Morphological analysis of the forelimb buds of E9.5 wild-type and Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− mutant embryos by scanning electron microscopy indicated that the mutant embryos contain nascent limb buds that are significantly smaller than wild-type limb buds (Fig. 5a,b). We analyzed the expression of molecular markers for the AER and the distal mesoderm. Histological sections of E9.5 wild-type and mutant embryos, hybridized with a Pax3 probe, indicated that cells from the dermamyotome containing presumed limb muscle precursors, migrate into the lateral plate mesoderm of both wild-type and mutant embryos (Fig. 5c,d). However, the early AER marker Fgf8 is abundantly expressed in wild-type embryos but not in mutant embryos (Fig. 5e,f). In addition, we examined the expression of Engrailed1 (En1), which is a marker for D–V polarity of the limb bud and is expressed in the ventral ectoderm even prior to the formation of an AER (Parr and McMahon 1995; Loomis et al. 1996). En1 is also expressed at the mid-/hindbrain boundary and is a target of Wnt-1 signaling (Danielian and McMahon 1996). In Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos, En1 is not expressed in the forelimb bud, although abundant expression can be detected at the mid-/hindbrain boundary (Fig. 5g,h). The maintenance of En1 expression in the mid-/hindbrain boundary suggests that Wnt1 signaling in this region of the embryo is mediated by another member of the LEF-1/TCF family of transcription factors, or is independent of these proteins.

Figure 5.

Limb bud defects in Lef1−/− Tcf1−/− embryos. (a,b) Morphology of the forelimb field in wild-type and mutant embryos. SEM pictures of E9.5 embryos showing the cervico-thoracic region at the forelimb level. A well formed limb bud (LB) is seen in the wild-type embryo, whereas the Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryo only shows indications of a protrusion in the lateral plate mesoderm (LPM) in the forelimb bud region. The mutant embryo shows somites rostral, but not caudal to the prospective forelimb bud. The somites (S) of the mutant embryo are covered with ectoderm that resembles that covering the dorsal part of the neural tube. (c,d) Transverse sections of wild-type and mutant embryos at the level of the forelimb bud (FL) that were hybridized with Pax3. Both wild-type and mutant embryos show migration of Pax3 expressing myogenic precursors into the lateral plate mesoderm. (NT) The neural tube. (e–l) Analysis of molecular markers in E9.5 wild-type and mutant embryos by whole mount in situ hybridization. Expression of Fgf8, an early marker of the AER in the developing forelimb bud is detected in a wildtype (e) but not mutant embryo (f). (arrowhead) Position of the forelimb bud in these and the other panels. (g,h) Expression of En1 is detected in the ventral region of the wild-type but not mutant forelimb bud. However, En1 expression is detected at the mid-hindbrain boundary. (i,j) Expression of Lmx1b, a marker of the dorsal mesenchyme of the emerging limb buds (Cygan et al. 1997) is detected in both the wild-type and mutant embryos. However, the region of Lmx1b expression is broadened in the mutant limb bud and the level of Lmx1b expression is lower relative to the wild type limb bud. The expression of Lmx1b at the mid-hindbrain boundary is not affected in the mutant embryo. (k,l) Transverse sections at the level of the limb bud of the embryos shown in (i and j) stained with fast neutral red. Lmx1b expression is restricted to the dorsal mesenchyme of the wild-type limb bud (i) but is extended along the entire limb margin in the mutant embryo (j).

The absence of detectable En1 expression in the limb bud may also reflect a dorsalization of the limb (Cygan et al. 1997; Loomis et al. 1998). Therefore, we examined the expression of Lmx1b, which, like Wnt7a, is involved in dorsal cell fate decisions (Riddle et al. 1995; Vogel et al. 1995; Cygan et al. 1997). Lmx1b expression is detected in the limb buds of compound mutant embryos (Fig. 5j), although the level of expression is lower and the area of expression is broadened relative to the wild-type embryo (Fig. 5i). In transverse sections of the wild-type limb buds, Lmx1b is restricted to the dorsal mesenchyme (Fig. 5k), whereas expression was found in both dorsal and ventral mesenchyme of the Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− limb bud (Fig. 5l). This pattern of Lmx1b expression is reminiscent of an earlier stage limb bud and the lack of a D–V border has been shown to result in a failure to form an AER (Johnson and Tabin 1997). Finally, we examined the expression of the mesoderm marker Msx1 and found that the level of expression is reduced in the mutant limb buds and the domain of expression is broadened (data not shown). This broadened expression domain of Lmx1b and Msx1 may reflect an impairment of regional specification of the limb bud in the Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− embryos. Expression of Wnt5a, which is normally expressed in the ventral limb ectoderm and in the limb mesenchyme (Parr et al. 1993), was not detected in the Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− limb buds (Fig. 3l). Taken together, these data indicate that the transcription factors LEF-1 and TCF-1 also regulate limb development in a redundant manner.

Discussion

Our study shows that null mutations in the transcription factor genes Lef1 and Tcf1 result in a defect in the formation of paraxial mesoderm, which is virtually identical to that seen in Wnt3a-deficient mice. In particular, the Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− mice form excess neural ectoderm at the expense of paraxial mesoderm. This presumed role of Wnt3a signaling through LEF-1/TCF proteins in a cell fate decision is consistent with the recent finding that injection of a dominant-negative Wnt into premigratory neural crest cells of zebra fish promotes neuronal fates at the expense of pigment cells (Dorsky et al. 1998). In addition, signaling by Wnt1 and Wnt3a was shown to regulate the expansion of dorsal neural precursors in mouse embryos (Ikeya et al. 1997). The reduction in size of the telencephalic vesicle may also be related to the deficiency of signaling by Wnt3a, which is expressed together with other Wnt proteins at the medial edge of the telencephalon (Grove et al. 1998). Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− mice also fail to form the placenta, a phenotype seen in a less pronounced form in Wnt2-deficient mice (Monkley et al. 1996). Thus, our analysis shows a redundant role of these transcription factors in signaling by at least one, and most likely multiple Wnt proteins in the mouse.

The defect of limb development in Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− mice suggests a role of Wnt signaling in this developmental process. To date, the only Wnt mutation that has been shown to have a defect in limb development is Wnt7a (Parr and McMahon 1995). However, recent studies in the chick, in which an activated form of β-catenin was expressed in limb buds via retroviral transfer, showed that Wnt-7a functions in limb morphogenesis through a β-catenin independent pathway (Kengaku et al. 1998). In contrast, a dominant-negative form of LEF-1 interfered with the function of Wnt3a in inducing the expression of Bmp2, Fgf4, and Fgf8 in the AER (Kengaku et al. 1998). Moreover, this study showed that Wnt3a upregulates expression of Lef1 in the mesoderm and acts through this transcription factor (Kengaku et al. 1998). In the mouse, Wnt3a, which is distinct from Wnt3, is not expressed at a detectable level, suggesting that LEF-1 and TCF-1 may mediate the effects of another Wnt signal. The limb bud phenotype of Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− mice is reminiscent of that of the limbless mutant in chick, which initiates limb bud morphogenesis, but fails to express En1, Fgf4, Fgf8, and Tcf1, and has a defect preceding the formation of an AER (Grieshammer et al. 1996; Noramly et al. 1996; Ros et al. 1996). The lack of AER expression in the Lef1−/− Tcf1−/− mice can be accounted for by an arrest of limb bud development prior to the formation of an AER. According to this view, development of the limb bud requires Wnt signaling through LEF/TCF proteins in the mesenchyme. Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− limb buds also fail to express Fgf8, consistent with the role of Wnt signaling in inducing Fgf8 in the chick (Kengaku et al. 1998).

The pronounced similarity of the Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− and Wnt3a−/− phenotypes raises the question of the role of these transcription factors in signaling by other Wnt proteins that are expressed in spatially and temporally overlapping patterns in early mouse development. The absence of Wnt5a expression in both Lef1−/−Tcf1−/− and Wnt3a−/− embryos suggests that LEF-1 and TCF proteins could also regulate signaling by multiple Wnt proteins in an indirect manner through feedback loops. However, we cannot rule out that the lack of expression of specific Wnt proteins reflects the absence of specific cell types. In addition, some Wnt proteins, such as Wnt7a in the chick, may not involve a transcriptional response by LEF-1/TCF proteins (Kengaku et al. 1998), and conversely not all transcriptional activities of LEF-1 are dependent on association with β-catenin (Hsu et al. 1998). Therefore, analysis of additional mutant alleles of Lef1 and Tcf1 will be required to further dissect the regulatory network of Wnt signaling.

Materials and methods

Mouse breeding and genotyping

C57BL/6 mice were used as wild-type strain and were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). LEF-1- and TCF-1- deficient mice were generated as described previously (van Genderen et al. 1994; Verbeek et al. 1995). Double mutant embryos were obtained from crosses between compound heterozygotes Lef1−/+, Tcf1−/+ mice. Genotyping of all embryos was performed by PCR analysis of genomic DNA extracted from the yolk sacs using the following primers: Tcf1(VII):a, 5′-GAGCCAAGGTCATTGCTGAGTGC; Tcf1(VII):b, 5′-TAGTTATCCCGCGCGGACCAG; and PGKP2, 5′-GGTTGGCGCTACCGGTGGATGTGG to screen for Tcf1(VII)−/− mice, and D8, 5′-CCGTTTCAGTGGCACGCCCTCTCC, LPP2.2, 5′-TGTCTCTCTTTCCGTGCTAGTTC and NEO, 5′-ATGGCGATGCCTGCTTGCCGAATA to screen for Lef1−/− mice.

Histology and immunohystochemistry

Embryos were dissected out and fixed in Carnoy′s fixative (60% ethanol, 30% chloroform, 10% acetic acid) at the indicated ages, dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 7 μm, and stained with 0.1% cresyl violet for conventional analysis.

Immunohystochemistry was performed on transverse sections of embryos similarly processed with a rabbit polyclonal serum raised against the full-length LEF-1 protein at 1/50 dilution as described in (van Genderen et al. 1994). Immunodetection was performed with the ABC method (ABC Elite Kit, Vector Labs).

Scanning electron microscopy

Embryos were taken from timed pregnancies and fixed at 4°C overnight in 4% PFA in PBS. Embryos were then washed in PBS, dehydrated in ethanol, critically point dried, placed on brass stubs, and coated with 25 nm of gold–palladium. Specimens were viewed and photographed in a JEOL 840 scanning electron microscope.

Whole mount in situ hybridization

Embryos were fixed and processed following published protocols (Henrique et al. 1995) with the following modifications: Endogenous peroxidases were quenched with 6% H2O2 for 2 hr prior to proteinase K digestion and hybridization. Hybridization was performed for 40 hr at 63°C in 5× SSC (pH 4.5), 50% formamide, 5 mm EDTA, 50 μg/ml yeast tRNA, 0.2% Tween 20, 0.5% CHAPS, and 100 μg/ml heparin. Color was developed with NBT/BCIP substrate. Embryos were postfixed and photographed in 50% glycerol in PBS. After color developing, some embryos were washed in PBS, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS, embedded in OCT, cryosectioned at 20 μm and stained with nuclear fast red before mounting in Permount.

Probes

In vitro-transcribed and DIG-labeled antisense RNA probes were obtained from the following genes: Lef-1 from amino acids 1–243 (Travis et al. 1991), Tcf-1 clone M2a (Oosterwegel et al. 1993), Tbx6, Tcf-3, and Tcf-4 IMAGE clones 1636895, 444295, and 764951, respectively (Lennon et al. 1996), Pax-1 (Wailin et al. 1994), Pax-3 (Goulding et al. 1991), Notch-1 transmembrane and cytoplasmic region probe (del Amo et al. 1993), Wnt-1, Wnt-3a, and Wnt5a (Parr et al. 1993), Fgf8 (Martin 1998), Engrailed1 (Loomis et al. 1996), Msx1 (Ros et al. 1992), Lmx1b (Cygan et al. 1997).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Peter Gruss, Rudi Balling, Roel Nusse, Randy Johnson, and Jackie Papkoff for gifts of cDNA probes. We thank Andrew McMahon and John Rubenstein for discussions and Gail Martin, Cliff Tabin, and Didier Stainier for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by funds from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute to R.G.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL rgross@itsa.ucsf.edu; FAX: (415) 476-8201.

References

- Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kühl M, Bruhn L, Weklich D, Grosschedl R, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of β-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996;382:638–642. doi: 10.1038/382638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannon M, Gomperumoy M, Moon RT, Kimelman D. A β-catenin/XTcf-3 complex binds to the siamois promoter to regulate dorsal axis specification in Xenopus. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:2359–2370. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn L, Munnerlyn A, Grosschedl R. ALY, a context-dependent coactivator of LEF-1 and AML-1, is required for TCRα enhancer function. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:640–653. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.5.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner E, Peter O, Schweizer L, Basler K. Pangolin encodes a Lef-1 homologue that acts downstream of Armadillo to transduce the wingless signal in Drosophila. Nature. 1997;385:829–833. doi: 10.1038/385829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, Nusse R. Wnt signaling: A common theme in animal development. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:3286–3305. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo RA, Cox RT, Moline MM, Roose J, Polevoy GA, Clevers H, Peifer M, Bejsovec A. Drosophila Tcf and Groucho interact to repress Wingless signaling activity. Nature. 1998;395:604–608. doi: 10.1038/26982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DL, Papaioannou VE. Three neural tubes in mouse embryos with mutations in the T-Box gene Tbx6. Nature. 1998;391:695–697. doi: 10.1038/35624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DL, Agulnik I, Hancock S, Silver LM, Papaioannou VE. Tbx6, a mouse T-Box gene implicated in paraxial mesoderm formation at gastrulation. Dev Biol. 1996;180:534–542. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cygan JA, Johnson RL, McMahon AP. Novel regulatory interactions revealed by studies of murine limb pattern in Wnt-7a and En-1 mutants. Development. 1997;124:5021–5032. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.24.5021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielian PS, McMahon AP. Engrailed-1 as a target of the Wnt-1 signaling pathway in vertebrate midbrain development. Nature. 1996;383:332–334. doi: 10.1038/383332a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Amo FF, Gendron-Maguire M, Swiatek PJ, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Grindley T. Clining analysis, and chromosomal localization of Notch-1, a mouse homologue of Drosophila Notch. Genomics. 1993;15:259–264. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C, Bedford M, Li C, Xu X, Yang X, Dunmore J, Leder P. Fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 (FGFR-1) is essential fro normal neural tube and limb development. Dev Biol. 1997;185:42–54. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsky RI, Moon RT, Raible DW. Control of neural crest cell fate by the Wnt signaling pathway. Nature. 1998;396:370–373. doi: 10.1038/24620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulding MD, Chalepakis G, Deutsch U, Erselius JR, Gruss P. Pax-3, a novel murine DNA binding protein expressed during early neurogenesis. EMBO J. 1991;10:1135–1147. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshammer U, Minowanda G, Pisenti JM, Abbott UK, Martin GR. The chick limbless mutation causes abnormalities in limb bud dorsal-ventral patterning: Implications for the mechanism of apical ridge formation. Development. 1996;122:3851–3861. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove EA, Tole S, Limon J, Yip L, Ragsdale CW. The hem of the embryonic cerebral cortex is defined by the expression of multiple Wnt genes and is compromised in Gli3-deficient mice. Development. 1998;125:2315–2325. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrique D, Adams J, Myat A, Chitnis A, Lewis J, Ish-Horowicz D. Expression of a Delta homologue in prospective neurons in the chick. Nature. 1995;375:787–790. doi: 10.1038/375787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S-C, Galceran J, Grosschedl R. Modulation of transcriptional regulation by LEF-1 in response to Wnt-1 signaling and association with β-catenin. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4807–4818. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber O, Korn R, McLaughlin J, Ohsugi M, Herrmann BG, Kemler R. Nuclear localization of β-catenin by interaction with transciption factor LEF-1. Mech Dev. 1996;59:3–10. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00597-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya M, Lee SMK, Johnson JE, McMahon AP. Wnt signaling required for expansion of neurol crest and CNS progenitors. Nature. 1997;389:966–970. doi: 10.1038/40146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Tabin CL. Molecular models for vertebrate limb development. Cell. 1997;90:979–990. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kengaku M, Capdevila J, Rodriguez-Esteban C, De La Peña J, Johnson RL, Belmonte JCI, Tabin CJ. Distinct WNT pathways regulating AER formation and dorsoventral polarity in the chick limb bud. Science. 1998a;289:1274–1277. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5367.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korinek V, Barker N, Willert K, Molenaar M, Roose J, Wagenaar G, Markman M, Lamers W, Destree O, Clevers H. Two members of the Tcf family implicated in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling during embryogenesis in the mouse. Mol Cell Biol. 1998a;18:1248–1256. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korinek V, Barker N, Moerer P, van Donselaar E, Huls G, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Depletion of epithelial stem-cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf-4. Nat Genet. 1998b;19:379–383. doi: 10.1038/1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwil K, Fariñas DMI, Galceran J, Grosschedl R. Lef1expression is activated by BMP-4 and regulates inductive tissue interactions in tooth and hair development. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1382–1394. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon G, Auffray C, Polymeropoulos M, Soares MB. The I.M.A.G.E. consortium: An integrated molecular analysis of genomes and their expression. Genomics. 1996;33:151–152. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levanon D, Goldstein R, Bernstein Y, Tang H, Goldenberg D, Stifani S, Paroush Z, Groner Y. Transcriptional repression by AML1 and LEF-1 is mediated by the TLE/Groucho corepressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:11590–11595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis CA, Harris EE, Michaud J, Wurst W, Hanks M, Joyner AL. The mouse Engrailed-1 gene and ventral limb patterning. Nature. 1996;382:360–363. doi: 10.1038/382360a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis CA, Kimmel RA, Tong CX, Michaud J, Joyner AL. Analysis of the genetic pathway leading formation of extopic apical ectodermal ridges in mouse Engrailed-1 mutant limbs. Development. 1998;125:1137–1148. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GR. The roles of FGFs in the early development of vertebrate limbs. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1571–1586. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenaar M, van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Peterson-Maduro J, Gosave S, Korinek V, Roose J, Destree O, Clevers H. Xtcf-3 transciption factor mediates β-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopusembryos. Cell. 1996;86:391–399. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monkley SJ, Delaney SJ, Pennisi DJ, Christiansen JH, Wainwright BJ. Targeted disruption of the Wnt2gene results in placentation defects. Development. 1996;122:3343–3353. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon RT, Brown JD, Torres M. WNTs modulate cell fate and behavior during vertebrate development. Trends Genet. 1997;13:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noramly S, Pisenti J, Abbott U, Morgan B. Gene expression in the limbnessmutant: Polarized gene expression in the abscence of Shh and an AER. Dev Biol. 1996;179:339–346. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterwegel M, van de Wetering M, Timmerman J, Kruisbeek A, Destree O, Meijlink F, Clevers H. Differential expression of the HMG box factors TCF-1 and LEF-1 during murine embryogenesis. Development. 1993;118:439–448. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr BA, McMahon AP. Dorsalizing signal Wnt-7arequired for normal polarity of D-V and A-P axes of mouse limb. Nature. 1995;374:350–353. doi: 10.1038/374350a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr BA, Shea MJ, Vassileva G, McMahon AP. Mouse Wntgenes exhibit discrete domains of expression in the early embryonic CNS and limb buds. Development. 1993;119:247–261. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle RD, Ensini M, Nelson C, Tsuchida T, Jessell TM, Tabin C. Induction of the LIM homeobix gene Lmx1 by WNT7a establishes dorsoventral pattern in the vertebrate limb. Cell. 1995;83:631–640. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roose J, Molenaar M, Peterson J, Hurenkamp J, Brantjes H, Moerer P, van der Wetering M, Destree O, Clevers H. The Xenopus Wnt effector CTcf3 interacts with Groucho-related transcriptional repressors. Nature. 1998;395:608–612. doi: 10.1038/26989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros MA, Lyons G, Kosher RA, Upholt WB, Coelho CND, Fallon JF. Apical ridge dependent and independent mesodermal domains of GHox-7 and GHox-8 expression in chick limb buds. Development. 1992;116:811–818. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.3.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros MA, Lopez-Martinez A, Simandl BK, Rodriguez C, Izpisua-Belmonte J-C, Dahn R, Fallon JF. The limb field mesoderm determines initial limb bud anteroposterior asymmetry and budding independent of sonic hedgehog or apical ectodermal gene expressions. Development. 1996;122:2319–2330. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark K, Vainio S, Vassileva G, McMahon AP. Epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney regulated by Wnt-4. Nature. 1994;372:679–683. doi: 10.1038/372679a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada S, Stark KL, Shea MJ, Vassilevea G, McMahon JA, McMahon AP. Wnt-3αregulates somite and tailbud formation in the mouse embryo. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:174–189. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam PPL, Beddington RSP. The formation of mesodermal tissues in the mouse embryo during gastrulation and early organogenesis. Development. 1987;99:109–126. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam PPL, Beddington RSP. Establisment and organization of germ layers in the gastrulating mouse embryo. Ciba Found Symp. 1992;165:27–41. doi: 10.1002/9780470514221.ch3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis A, Amsterdam A, Belanger C, Grosschedl R. LEF-1, a gene encoding a lymphoid-specific protein with an HMG domain, regulates T cell α enhancer function. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:880–894. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Dooijes D, Clevers H. Identification and cloning of TCF-1, a T lymphocyte-specific transciption factor containing a sequence-specific HMG box. EMBO J. 1991;10:123–132. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wetering M, Cavallo R, Dooijes D, van Beest M, van Es J, Loureiro J, Ypma A, Hursh D, Jones T, Bejsovec A, Peifer M, Mortin M, Clevers H. Armadillo co-activates transcription driven by the product of the Drosophila segment polarity gene dTCF. Cell. 1997;88:789–799. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81925-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Genderen C, Okamura R, Fariñas I, Quo R, Parslow T, Bruhn L, Grosschedl R. Development of several organs that require inductive epithelial mesenchymal interactions is impaired in LEF-1-deficient mice. Gene & Dev. 1994;8:2691–2703. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.22.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek S, Izon D, Hofhuis F, Robanus-Maandag E, te Riele H, van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Wilson A, MacDonald HR, Clevers H. An HMG-box-containing T-cell factor required for thymocyte differentiation. Nature. 1995;374:70–74. doi: 10.1038/374070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel A, Rodriguez C, Warnken W, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Dorsal cell fate specified by chick Lmx1 during vertebrate limb development. Nature. 1995;378:716–720. doi: 10.1038/378716a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltzer L, Bienz M. Drosophila CBP represses the transcription factor TCF to antagonize Wingless signaling. Nature. 1998;395:521–525. doi: 10.1038/26785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman ML, Fischer WH, Jones KA. A thymus-specific member of the HMG protein family regulates the human T cell receptor C α enhancer. Genes & Dev. 1991;5:656–669. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.4.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Y, Fujimori T, McMahon AP, Takada S. Evidence that absence of Wnt-3a signaling promotes neuralization instead of paraxial mesoderm development in the mouse. Dev Biol. 1997;183:234–242. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]