Abstract

Studies investigating the subcellular localization of periplasmic proteins have been hampered by problems with the export of green fluorescent protein (GFP). Here we show that a superfolding variant of GFP (sfGFP) is fluorescent following Sec-mediated transport and works best when the cotranslational branch of the pathway is employed.

TEXT

Subcellular localization studies of envelope proteins have been hampered by problems with the export of functional green fluorescent protein (GFP) (9). When exported to the periplasm in an unfolded conformation through the Sec system, commonly used variants of GFP fail to fold properly and do not fluoresce (9). To circumvent these issues, we and others have previously used GFP fusions exported in a folded conformation through the Tat system (2, 3, 20, 22). However, artificially routing protein fusions through the Tat system is unlikely to be effective in all cases. Several years ago it was shown that red fluorescent protein (RFP) derivatives do not share the transport difficulties of their GFP cousins; they can be effectively transported to the periplasm through the Sec system (5, 15). Although this has greatly expanded the range of protein localization experiments possible for studies of the cell envelope, colocalization studies involving two envelope proteins still must utilize at least one Tat-transported component.

Use of sfGFP in the periplasm.

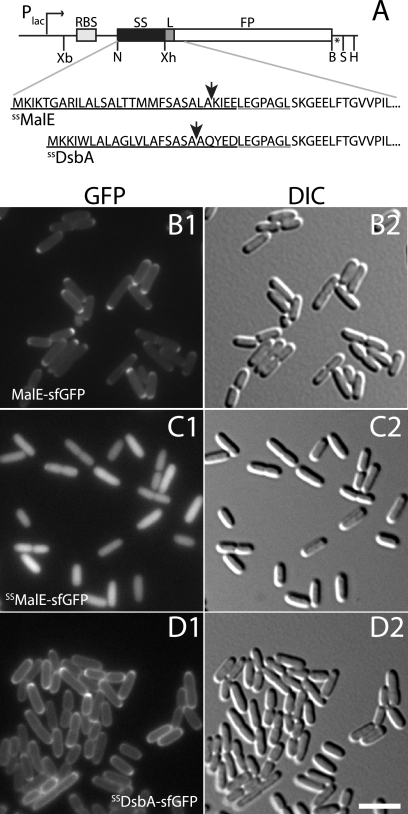

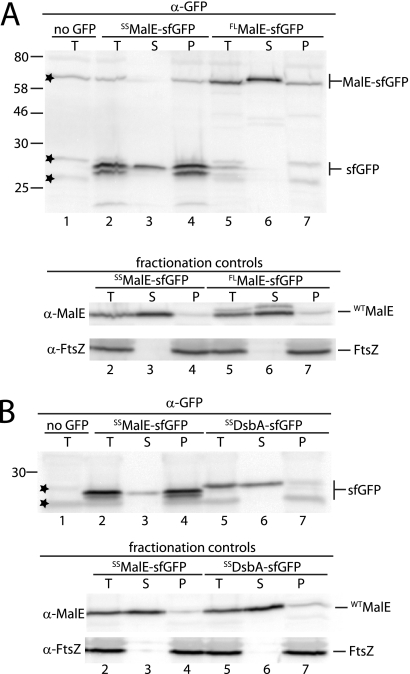

We investigated the potential utility of a superfolding derivative of GFP (sfGFP) (17) for periplasmic protein localization studies using previously described fluorescence microscopy methods (24). The coding sequence for sfGFP (17) was synthesized by Epoch Life sciences and used to make gene fusions. All fusions were placed under the control of the wild-type lac promoter (Plac). With the exception of pal-sfGFP, fusions were cloned in derivatives of CRIM vectors (12) for integration at the phage HK022 att site (attHK022) of TB28 (MG1655 ΔlacIZYA) cells (3) using the helper plasmid pTB102 as described previously (4, 12). We first studied fusions of sfGFP to the well-characterized Sec substrate MalE. Cells producing MalE-sfGFP displayed a polar fluorescent signal with some fluorescence detectable around the periphery of many cells (Fig. 1B). Polar accumulation of the exported fusion protein was expected as this was also frequently observed for Tat-exported GFP (2, 3, 20, 22). Cell fractionation and immunoblotting using goat anti-GFP antibodies (catalog no. 600-101-215; Rockland Immunochemicals), performed as described previously (2), confirmed that the vast majority of MalE-sfGFP was indeed exported (Fig. 2A, lanes 5 to 7). Thus, unlike other commonly used GFP derivatives, sfGFP is folded and fluorescent following Sec export.

Fig. 1.

Visualization of exported sfGFP. (A) Schematic diagram of expression constructs for the production of exported fluorescent proteins (FP). Signal peptides (SS) used for export are underlined in black below the diagram, and the gray underlines highlight the linker (L) sequence. Arrows point to sites of leader peptidase processing. RBS, ribosome-binding site; Xb, XbaI; N, NdeI; Xh, XhoI; B, BamHI; S, SalI; H, HindIII. The asterisk indicates a stop codon. (B to D) Cells of TB28 (wild type) harboring integrated expression constructs attHKTB228 (Plac::malE-sfGFP) (B), attHKTB262 (Plac::SSmalE-sfGFP) (C), or attHKTB263 (Plac::SSdsbA-sfGFP) (D) were grown at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 to 0.7 in M9 maltose supplemented with 250 μM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and visualized with GFP (panel 1) and differential interference contrast (DIC) (panel 2) optics. Bar equals 4 μm.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of sfGFP export by subcellular fractionation and immunoblotting. (A) Cells of TB28 (wild type [WT]) harboring integrated expression constructs attHKTB262 (Plac::SSmalE-sfGFP) (lanes 2 to 4) or attHKTB228 (Plac::malE-sfGFP) (lanes 5 to 7) were grown at 30°C in LB supplemented with 0.2% maltose and 500 μM IPTG. A portion of the resulting cultures was used to prepare a total cell extract (T). The remaining cells were converted to spheroplasts and pelleted by centrifugation. The resulting pellet (P) and supernatant (S) fractions, along with the total cell extract, were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using antisera directed against GFP (Rockland), MalE (NEB), and FtsZ. FtsZ and native MalE served as fractionation controls for the cytoplasm and periplasm, respectively. Extract from TB28 (WT) cells without a fusion protein controlled for the specificity of the GFP antisera (lane 1). The positions of sfGFP fusion proteins and molecular mass standards (in kDa) are indicated on the right and left of the immunoblot, respectively. Stars indicate nonspecific bands. Full-length MalE is abbreviated FLMalE. (B) Same as described for panel A except that the export of sfGFP was compared between TB28 (WT) cells producing fusions from the integrated expression constructs attHKTB262 (Plac::SSmalE-sfGFP) (lanes 2 to 4) and attHKTB263 (Plac::SSdsbA-sfGFP) (lanes 5 to 7).

We next generated a construct encoding just the signal sequence of MalE (SSMalE) fused to sfGFP to serve as a base vector for the production of a variety of different exported fusion proteins (Fig. 1A). To our surprise, cells expressing SSMalE-sfGFP displayed a fluorescent signal consistent with the fusion protein being cytoplasmic (Fig. 1C). Cell fractionation and immunoblotting confirmed that while a small portion of the fusion protein was exported, the majority remained in the spheroplast fraction (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 to 4). Thus, while the export of full-length MalE-sfGFP was relatively efficient, that of SSMalE-sfGFP was largely blocked, presumably because it folds prior to transport. The difference in export efficiencies between the fusions may be due, in part, to the ability of SecB to maintain full-length MalE-sfGFP in a secretion-competent, unfolded conformation prior to export (6, 25). Also, it was shown previously that MalE and many other secretory proteins are transported by both cotranslational and posttranslational secretion pathways (14). We therefore assume that longer fusions are more likely to engage the Sec translocon before translation of the protein is complete and be exported cotranslationally more often than short proteins like SSMalE-sfGFP.

Efficient cotranslational export of sfGFP.

Our results with the MalE fusions suggested that cotranslational export of sfGFP may be required to prevent it from folding in the cytoplasm and blocking export. Beckwith and coworkers have identified a subset of signal sequences that direct secretory proteins primarily through the cotranslational branch of the Sec export pathway (13, 21). The signal peptide of DsbA was one such export signal. To test whether or not SSDsbA could direct efficient export of sfGFP to the periplasm, we constructed an SSDsbA-sfGFP fusion (Fig. 1A) and compared its export to that of SSMalE-sfGFP. Unlike SSMalE-sfGFP, cells expressing the SSDsbA-sfGFP fusion displayed a largely peripheral fluorescent signal with some polar accumulation (Fig. 1D). Subcellular fractionation indicated that the SSDsbA-sfGFP was indeed transported efficiently (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 to 7). We conclude that fluorescent sfGFP can be efficiently transported to the periplasm provided that it is exported though a predominantly cotranslational pathway. Similar attempts to export GFPmut2 (7) using SSDsbA did not result in a fluorescent signal (10) (data not shown). Contrary to our results, Fisher and DeLisa (10) recently reported that an SSDsbA-sfGFP fusion accumulated in the cytoplasm and that the fraction transported to the periplasm was largely inactive (10). This discrepancy likely reflects differences in the levels of protein produced in the two studies. Fisher and DeLisa produced relatively high levels of SSDsbA-sfGFP from a multicopy plasmid using a strong promoter (10), while our fusions were produced from a single locus in the chromosome under the control of Plac.

mCherry can be transported to the periplasm using SSMalE or SSDsbA.

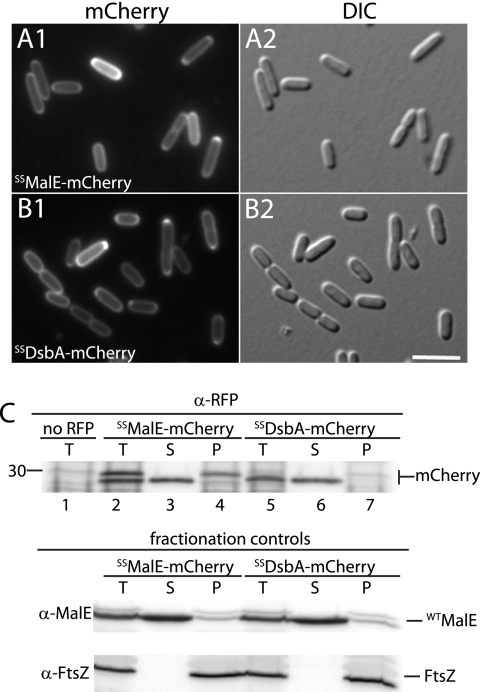

Based on our results with sfGFP, we wondered if the transport of RFP derivatives like mCherry also requires the use of the cotranslational pathway. We therefore constructed both SSMalE-mCherry and SSDsbA-mCherry fusions for a comparison. In contrast to sfGFP fusions, cells expressing both SSMalE-mCherry and SSDsbA-mCherry displayed a peripheral fluorescence signal consistent with proper transport to the periplasm (Fig. 3A and B). This was confirmed by cellular fractionation experiments and mCherry detection with rabbit anti-RFP antisera (catalog no. 600-401-379; Rockland Immunochemicals) (Fig. 3C). When SSMalE was used, two mCherry species present in roughly equal amounts were apparent in the immunoblots, probably corresponding to the slower-migrating precursor and faster-migrating mature form (Fig. 3C, lanes 2 to 4). Consistent with these assignments, the mature form was exclusively located in the periplasmic fraction, whereas the precursor was limited to the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 3C, lanes 2 to 4). Compared to that of SSMalE, the export of mCherry directed by SSDsbA appeared to be much more efficient. Only the mature form of the fusion was observed, and it was exclusively found in the periplasmic fraction (Fig. 3C, lanes 5 to 7). We conclude that mCherry can be effectively transported to the periplasm for protein localization experiments regardless of which branch of the Sec transport pathway is used.

Fig. 3.

mCherry is functional following post- or cotranslational Sec export. (A and B) Cells of TB28 (WT) containing the integrated expression constructs attHKTB317 (Plac::SSmalE-mCherry) or attHKTU136 (Plac::SSdsbA-mCherry) were grown at 30°C to an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.7 in M9 maltose supplemented with 100 or 50 μM IPTG, respectively, and visualized with mCherry (panel 1) and DIC (panel 2) optics. Bar equals 4 μm. (C) The same strains were grown and processed for cell fractionation and immunoblotting as described for Fig. 2A.

Using sfGFP for protein localization studies.

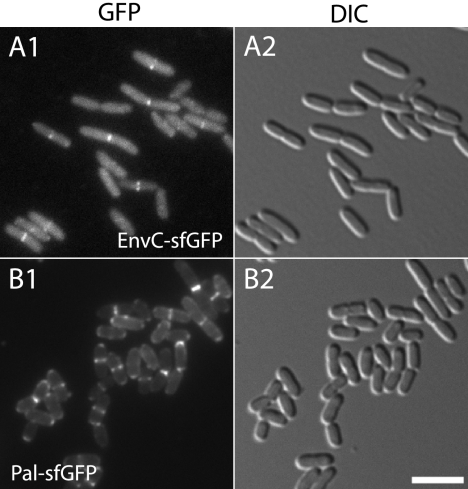

To test the effectiveness of sfGFP for protein localization experiments in the periplasm, we studied the localization of sfGFP fusions to EnvC and Pal, two exported proteins previously shown to be recruited to the division site using a Tat-exported GFPmut2 fusion (EnvC) and/or a monomeric RFP (mRFP) fusion (EnvC and Pal) (3, 11, 24). Both the EnvC-sfGFP and Pal-sfGFP fusions were constructed to use their native export signals for transport to the periplasm. When produced in cells lacking native EnvC, the EnvC-sfGFP fusion corrected the mild chaining defect of the mutant strain (data not shown) and localized to the septum as expected from previous results (Fig. 4A) (3). Similarly, the Pal-sfGFP fusion corrected the Pal− chaining and membrane blebbing phenotypes (data not shown) and displayed the expected septal localization pattern when produced in Pal− cells (Fig. 4B) (11). Thus, C-terminal sfGFP fusion proteins can be used for protein localization experiments in the periplasm even when they are not specifically targeted through the signal recognition particle (SRP)-dependent cotranslational Sec export pathway using SSDsbA. As described above for the MalE-sfGFP fusion, this probably works because many secretory proteins are exported, at least in part, through a cotranslational mechanism (14).

Fig. 4.

Localization of EnvC and Pal shown using sfGFP. (A and B) Cells of TB140(attHKTB226) [ΔenvC(Plac::envC-sfGFP)] (A) or MG5/pTB223 (Δpal/Plac::pal-sfGFP) (B) were grown at 30°C to an OD600 of 0.5 to 0.7 in M9 maltose supplemented with 0 or 10 μM IPTG and were visualized using GFP (panel 1) or DIC (panel 2) optics. Bar equals 4 μm. pTB223 is a multicopy plasmid derived from pMLB1113 (8).

Conclusion.

We have shown that sfGFP can be used to study the subcellular localization of exported proteins. In an accompanying report (18), we use sfGFP to study the localization of the cell separation factor AmiB and perform colocalization experiments in the periplasm using both sfGFP and mCherry fusion proteins. Three recent reports also highlight the effectiveness of sfGFP for protein localization experiments in the periplasm (16, 19, 23).

ADDENDUM

While the manuscript was in preparation, Aronson et al. (1) also reported that fluorescent sfGFP can be exported to the periplasm.

Acknowledgments

The idea to use sfGFP for periplasmic localization studies was based on a suggestion from Gregory Phillips from Iowa State University.

This work was supported by the Massachusetts Life Science Center, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI083365-01A1). T.G.B. holds a Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aronson D. E., Costantini L. M., Snapp E. L. 2011. Superfolder GFP is fluorescent in oxidizing environments when targeted via the Sec translocon. Traffic 12:543–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bernhardt T. G., de Boer P. A. J. 2003. The Escherichia coli amidase AmiC is a periplasmic septal ring component exported via the twin-arginine transport pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1171–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bernhardt T. G., de Boer P. A. J. 2004. Screening for synthetic lethal mutants in Escherichia coli and identification of EnvC (YibP) as a periplasmic septal ring factor with murein hydrolase activity. Mol. Microbiol. 52:1255–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bernhardt T. G., de Boer P. A. J. 2005. SlmA, a nucleoid-associated, FtsZ binding protein required for blocking septal ring assembly over chromosomes in E. coli. Mol. Cell 18:555–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen J. C., Viollier P. H., Shapiro L. 2005. A membrane metalloprotease participates in the sequential degradation of a Caulobacter polarity determinant. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1085–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Collier D. N., Bankaitis V. A., Weiss J. B., Bassford P. J. 1988. The antifolding activity of SecB promotes the export of the E. coli maltose-binding protein. Cell 53:273–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cormack B. P., Valdivia R. H., Falkow S. 1996. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Gene 173:33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Boer P. A., Crossley R. E., Rothfield L. I. 1989. A division inhibitor and a topological specificity factor coded for by the minicell locus determine proper placement of the division septum in E. coli. Cell 56:641–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feilmeier B. J., Iseminger G., Schroeder D., Webber H., Phillips G. J. 2000. Green fluorescent protein functions as a reporter for protein localization in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:4068–4076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fisher A. C., DeLisa M. P. 2008. Laboratory evolution of fast-folding green fluorescent protein using secretory pathway quality control. PLoS One 3:e2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gerding M. A., Ogata Y., Pecora N. D., Niki H., de Boer P. A. J. 2007. The trans-envelope Tol-Pal complex is part of the cell division machinery and required for proper outer-membrane invagination during cell constriction in E. coli. Mol. Microbiol. 63:1008–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haldimann A., Wanner B. L. 2001. Conditional-replication, integration, excision, and retrieval plasmid-host systems for gene structure-function studies of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 183:6384–6393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huber D., et al. 2005. Use of thioredoxin as a reporter to identify a subset of Escherichia coli signal sequences that promote signal recognition particle-dependent translocation. J. Bacteriol. 187:2983–2991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Josefsson L. G., Randall L. L. 1981. Different exported proteins in E. coli show differences in the temporal mode of processing in vivo. Cell 25:151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lewenza S., Vidal-Ingigliardi D., Pugsley A. P. 2006. Direct visualization of red fluorescent lipoproteins indicates conservation of the membrane sorting rules in the family Enterobacteriaceae. J. Bacteriol. 188:3516–3524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paradis-Bleau C., et al. 2010. Lipoprotein cofactors located in the outer membrane activate bacterial cell wall polymerases. Cell 143:1110–1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pédelacq J.-D., Cabantous S., Tran T., Terwilliger T. C., Waldo G. S. 2006. Engineering and characterization of a superfolder green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peters N., Dinh T., Bernhardt T. G. 2011. A fail-safe mechanism in the septal ring assembly pathway generated by the sequential recruitment of cell separation amidases and their activators. J. Bacteriol. 193:4973–4983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Potluri L., et al. 2010. Septal and lateral wall localization of PBP5, the major D,D-carboxypeptidase of Escherichia coli, requires substrate recognition and membrane attachment. Mol. Microbiol. 77:300–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Santini C. L., et al. 2001. Translocation of jellyfish green fluorescent protein via the Tat system of Escherichia coli and change of its periplasmic localization in response to osmotic up-shock. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8159–8164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schierle C. F., et al. 2003. The DsbA signal sequence directs efficient, cotranslational export of passenger proteins to the Escherichia coli periplasm via the signal recognition particle pathway. J. Bacteriol. 185:5706–5713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thomas J. D., Daniel R. A., Errington J., Robinson C. 2001. Export of active green fluorescent protein to the periplasm by the twin-arginine translocase (Tat) pathway in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 39:47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Uehara T., Parzych K. R., Dinh T., Bernhardt T. G. 2010. Daughter cell separation is controlled by cytokinetic ring-activated cell wall hydrolysis. EMBO J. 29:1412–1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Uehara T., Dinh T., Bernhardt T. 2009. LytM-domain factors are required for daughter cell separation and rapid ampicillin-induced lysis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 191:5094–5107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weiss J. B., Ray P. H., Bassford P. J. 1988. Purified SecB protein of Escherichia coli retards folding and promotes membrane translocation of the maltose-binding protein in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:8978–8982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]