Abstract

Here we have characterized the Rickettsia prowazekii RP534 protein, a homologue of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU phospholipase A (PLA) secreted cytotoxin. Our studies showed that purified recombinant RP534 PLA possessed the predicted PLA2 and lyso-PLA2 activities based on what has been published for P. aeruginosa ExoU. RP534 also displayed PLA1 activity under the conditions tested, whereas ExoU did not. In addition, recombinant RP534 displayed a basal PLA activity that could hydrolyze phosphatidylcholine in the absence of any eukaryotic cofactors. Interestingly, the addition of bovine liver superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), a known activator of P. aeruginosa ExoU, resulted in an increased rate of RP534-catalyzed phospholipid hydrolysis, indicating that mechanisms of activation of the ExoU family of PLAs may be evolutionarily conserved. The mechanism of SOD1-dependent stimulation of RP534 was further examined using active site mutants and a fluorogenic phospholipid substrate whose hydrolysis by RP534 over a short time course is measureable only in the presence of SOD1. These studies suggest a mechanism by which SOD1 stimulates RP534 activity once it has bound to the substrate. We also show that antibody raised against RP534 was useful for immunoprecipitating active RP534 from R. prowazekii lysed cell extracts, thus verifying that this protein is expressed and active in rickettsiae isolated from embryonated hen egg yolk sacs.

INTRODUCTION

Rickettsia prowazekii is the etiological agent of epidemic typhus fever in humans and is a select agent. This reemerging pathogen is associated with louse infestations within the human population that occur as the result of social conditions that precipitate a breakdown in hygiene and sanitation (5, 25, 33). R. prowazekii is an obligate intracellular parasitic bacterium that attaches to host cells, actively stimulates its own entry, escapes from the phagosome, grows to large numbers in the cytoplasm, and eventually lyses the host cell (for reviews, see references 4, 20, 45, 47, and 49). It is well established that phospholipase A (PLA) activity plays an integral role in R. prowazekii pathogen/host interactions. Attachment of rickettsiae to host cells immediately activates a rickettsial PLA thought to be involved in pathogen entry (39, 46, 51, 54, 56). Furthermore, R. prowazekii-derived PLA activity is thought to be responsible for the continuous but noncytolytic release of host cell-free fatty acid to the culture medium during infection (51–53). In addition to parasitizing eukaryotic cells, R. prowazekii is able to lyse mammalian red blood cells (RBCs) in a PLA-dependent fashion, although the biological significance of RBC lysis remains unclear (13, 30–32, 40, 48, 50, 55, 57). Despite the prominent role of PLA in R. prowazekii pathogenesis, the biochemical properties of the culprit PLA(s) remain poorly characterized.

The R. prowazekii genome encodes two putative PLA proteins, RP534 and RP602 (6), which are annotated as members of the patatin superfamily of phospholipase/acyl hydrolase proteins. Patatin is a major storage glycoprotein in potatoes and possesses potent PLA/acyl hydrolase activity that becomes activated to serve as a defense mechanism against plant parasites (7, 21, 34, 41). Patatin-like PLAs are most highly homologous to eukaryotic group IV cytosolic PLA2α and group VI calcium-independent PLA2s, which are distinguished by a conserved serine-aspartic acid catalytic dyad within the active site (for reviews, see references 19 and 36). The amino-terminal half of the RP534 protein shows 27% sequence identity and 43% similarity to that of the ExoU PLA cytotoxin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, including perfect conservation of residues within the active site (36). ExoU is one of four major exotoxins of P. aeruginosa secreted by the type three secretion system (17) and has been linked to strains that cause severe respiratory disease (1, 15, 38). A defining characteristic of P. aeruginosa ExoU (PaExoU) is its reported dependence on a eukaryotic cell cytosolic cofactor(s) to elicit PLA activity (14, 27, 28, 36, 37, 44). Sato and coworkers have identified the eukaryotic copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) as a specific activator of ExoU activity in vitro (35). However, it remains unknown whether SOD1 is the only P. aeruginosa ExoU activator. Based on homology to P. aeruginosa ExoU, the goal of the present study was to characterize the R. prowazekii RP534 protein to determine if it is a bona fide PLA and whether it shares the SOD1-dependent activation properties of ExoU.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell growth and chemicals.

Escherichia coli was routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB Lennox) broth (Difco) supplemented with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin for plasmid maintenance (LBAp) at 37°C with aeration (200 rpm). Oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma, molecular biology enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs, fluorogenic phospholipids (PED6 and PED-A1) were purchased from Invitrogen, l-α-1-palmitoyl-2-[1-14C]arachidonyl-phosphatidylcholine, ([14C]PC-AA) (48 mCi/mmol, used at 0.05 μCi μl−1) and [1-14C]oleic acid ([14C]OA, 58.2 mCi/mmol, used at 0.1 μCi μl−1) were purchased from Perkin Elmer, and l-3-phosphatidylcholine, 1-palmitoyl-2-[1-14C]oleoyl ([14C]PC-OA) (56 mCi/mmol, used at 0.025 μCi μl−1) was from GE Healthcare. All other phospholipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids.

Expression plasmid construction and mutagenesis.

Molecular cloning techniques were previously described (18). The R. prowazekii RP534 gene was cloned into the pET16b expression vector (Novagen) to incorporate an amino-terminal decahistidine (N-His10) tag (plasmid designated pET16b-N-His10-RP534). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on pET16b-N-His10-RP534 using Stratagene's QuikChange system to change a serine residue at position 100 to an alanine (S100A). A second, separate mutant was constructed by changing an aspartic acid residue at position 246 to an alanine (D264A). A pET28-exoU plasmid (a kind gift from Partho Ghosh, University of California, San Diego) encoding P. aeruginosa ExoU (PaExoU) was used for subcloning of exoU to generate pET16b-N-His10-PaExoU.

All plasmids used in this study were verified by DNA sequencing using the ABI BigDye Terminator system (v.1), and reactions were resolved by the Iowa State DNA Facility on a fee-for-services basis. Sequence alignments were performed using the CodonCode Aligner software program (CodonCode Corp) or NCBI BLAST (2, 3).

Recombinant protein purification.

The pET16b-N-His10-RP534, pET16b-N-His10-RP534(S100A), pET16b-N-His10-RP534(D264A), and pET16b-N-His10-PaExoU expression vectors were independently introduced into the C41[DE3] expression strain of E. coli (24) by electroporation. Strains were regenerated routinely, since we have previously observed that expression vectors encoding R. prowazekii proteins are not stably maintained in expression-proficient E. coli strains. Transformants were not used for more than 1 week, but liquid cultures that had been induced for protein expression were routinely stored for weeks as cell pellets at −80°C prior to protein purification. Standard bacterial growth and protein purification conditions were as described previously (18), with the following modifications. Cell lysates were loaded onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin using a Bio-Rad Profinia protein purification system and sequentially washed with 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol (βME), pH 8.0, with 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 30 mM imidazole, and 10 mM βME, pH 8.0, and with 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM imidazole, and 10 mM βME, pH 8.0. Purified protein was exchanged into 50 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS), 50 mM NaCl, and 5 mM βME, pH 7.4, and stored at 4°C. Note that for purification of N-His10-PaExoU, βME was omitted from all buffers. Purified protein concentrations were determined by spectrophotometry at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of ∼35,730 M−1 cm−1. The purified RP534 proteins were stable for several weeks under these conditions. Purified proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10% Tris-glycine) and staining, and identities were verified by tandem mass spectroscopy at the USA MCI Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry Laboratory on a fee-for-service basis.

Purified N-His10-RP534 protein was used as an antigen to raise polyclonal rabbit antiserum (Sigma Genosys). Anti-N-His10-RP534 antibody was affinity purified using Pierce's Aminolink Plus immobilization kit as per the manufacturer's directions.

In vitro phospholipase activity assays.

The activities of purified recombinant PLA proteins were assayed using a radiolabeled phospholipid substrate incorporated into large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) as described in reference 37. The stock LUVs were a 2.5 μM equimolar mixture of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylserine (PS) (to give 5 μM total phospholipid) containing either 16.8 μM [14C]PC-OA or 38.2 μM [14C]PC-AA and were diluted 1:20 into the PLA assays. Purified PLA2 from Naja mossambica mossambica (Sigma) was used as a positive control. All samples were extracted using the acid-modified method of Bligh and Dyer (11, 22), resolved by thin-layer chromatography on silica gel G plates using the solvent system described in reference 16, and visualized by phosphorimaging (Cyclone; PerkinElmer). The PLA activity assay conditions are described in the legend to Fig. 1.

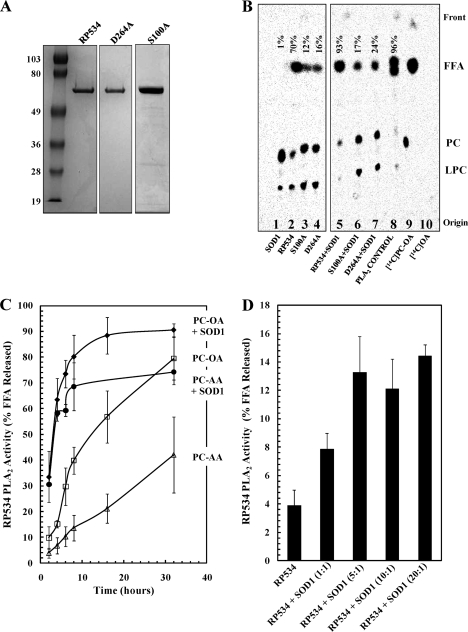

Fig. 1.

In vitro assay of R. prowazekii RP534 PLA activity using radiolabeled phospholipid substrates. (A) Recombinant N-His10-RP534, N-His10-RP534(S100A), and N-His10-RP534(D264A) were purified by immobilized-metal affinity chromatography (IMAC), resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Coomassie stained. The molecular mass markers shown to the left of the gels are in kDa. The expected size of the recombinant proteins is ∼70 kDa. (B) Purified recombinant N-His10-RP534, N-His10-RP534(S100A), and N-His10-RP534(D264A) were assayed for PLA activity using 14C-LUVs as substrates; the products were extracted, resolved by thin-layer chromatography, and visualized by phosphorimaging. Recombinant PLA proteins (0.01 μg μl−1) were incubated with or without bovine liver SOD1 (0.07 μg μl−1) with 0.25 μM PC/PS LUVs ([14C]PC-OA-labeled) in 20 mM MOPS-5 mM βME (pH 7.4) and incubated for 16 h at room temperature. Lane 8 shows a positive-control reaction using purified PLA2 (0.07 mU μl−1) from snake venom (Naja mossambica mossambica). Lanes 9 and 10 show the resolution of radiolabeled phospholipid and free fatty acid standards, respectively. Abbreviations to the right of the image are as follows: FFA, free fatty acid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine. Each lane is labeled at the bottom to denote the proteins added to the assay and labeled at the top to show the amount of FFA released, expressed as a percentage of the total counts in the entire lane by densitometry. (C) The N-His10-RP534 PLA2 activity was measured kinetically by expressing the amount of FFA released as a percentage of the total counts in the entire lane by densitometry. N-His10-RP534 (0.01 μg μl−1) was incubated with 0.25 μM PC/PS LUVs ([14C]PC-OA labeled) (open squares), 0.25 μM PC/PS LUVs ([14C]PC-OA labeled) and bovine liver SOD1 (0.07 μg μl−1) (filled diamonds), 0.25 μM PC/PS LUVs ([14C]PC-AA labeled) (open triangles), or 0.25 μM PC/PS LUVs ([14C]PC-AA labeled) and bovine liver SOD1 (0.07 μg μl−1) (filled circles). Error bars represent standard errors of the average for 2 experiments for [14C]PC-AA-labeled LUVs and 3 experiments for [14C]PC-OA-labeled LUVs. (D) The stoichiometry of bovine liver SOD1-mediated activation of N-His10-RP534 (at 0.01 μg μl−1) was determined using 0.25 μM PC/PS LUVs ([14C]PC-OA labeled) with SOD1 added at 1:1, 5:1, 10:1, and 20:1 molar ratios. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 90 min (during the linear part of the reaction) and extracted, and FFA release was determined as above. Error bars represent standard errors of the averages from 3 experiments.

The activities of the recombinant PLA proteins were also assayed using fluorogenic phospholipid substrates (Invitrogen). The PED6 [N-((6-(2,4-dinitrophenyl)amino)hexanoyl)-2-(4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s- indacene-3-pentanoyl)-1-hexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, triethylammonium salt] substrate has a fluorescent moiety conjugated at the sn-2 position and contains a dinitrophenyl group conjugated to the polar head group to provide intramolecular quenching. Thus, when the activity of a PLA2 hydrolyzes the sn-2 fatty acyl chain, the quenching is released and fluorescent signal is measured. The PED-A1 [(N-((6-(2,4-dinitrophenyl)amino)hexanoyl)-1-(4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-pentanoyl)-2-hexyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine)] substrate differs in that the fluorescent moiety is conjugated at the sn-1 position and the sn-2 fatty acyl group is nonhydrolyzable and is used to measure the activity of PLA1 enzymes. Substrates were dissolved into 50 mM MOPS-50 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, and assay conditions are described in the legends to Fig. 3, 4, and 5. Samples were removed from reactions at appropriate times and assayed for fluorescence on a NanoDrop 3300 Micro-Volume fluorospectrometer (Thermo Scientific) using 470-nm excitation/511 emission. The activity of the purified N-His10-RP534 protein was also tested in the presence of the PLA inhibitors methyl arachidonyl fluorophosphonate (MAFP) (concentrations are given in Fig. 3C) or arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone (AACOCF3) at 10 μM. MAFP was purchased as a methylacetate solution that was evaporated prior to dissolution of the MAFP directly into assay buffer. AACOCF3 was dissolved in ethanol and added directly to the PLA assays. Ethanol alone was included as a vehicle control.

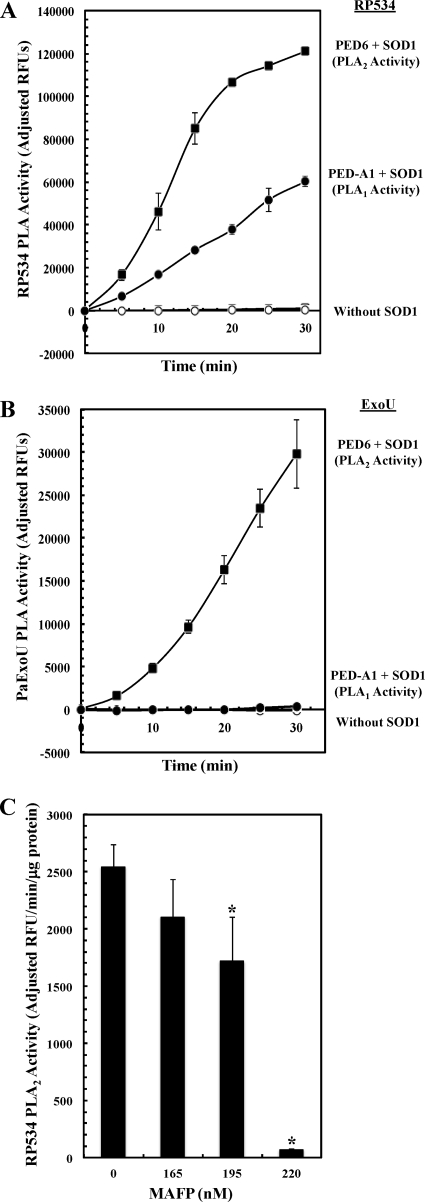

Fig. 3.

In vitro assay of R. prowazekii RP534 and P. aeruginosa ExoU PLA activities using fluorogenic phospholipid substrates. The N-His10-RP534 (A) or N-His10-PaExoU (B) PLA activities were measured using PED-A1 (PLA1 activity) and PED6 (PLA2 activity) as substrates. N-His10-RP534 was used at a concentration of 0.02 μg μl−1, and N-His10-PaExoU was used at a concentration of 0.02 μg μl−1 (these protein amounts are equivalent molar amounts). PLAs were incubated in 50 mM MOPS-50 mM NaCl (pH 7.4) with 29.7 μM PED6 (open squares), 29.7 μM PED6 and bovine liver SOD1 (0.2 μg μl−1) (filled squares), 29.7 μM PED-A1 (open circles), or 29.7 μM PED-A1 and bovine liver SOD1 (0.2 μg μl−1) (filled circles). The N-His10-RP534 reaction mixtures contained 5 mM βME, and the N-His10-PaExoU reaction mixtures contained no βME. Each data point is adjusted for background based on reactions incubated with substrate alone along the corresponding time course. Error bars represent standard errors of the averages from 3 experiments. (C) The effect of titrated amounts of the PLA2 inhibitor MAFP on N-His10-RP534 activity was tested using the PED6 substrate at a final concentration of 29.7 μM. N-His10-RP534 (0.03 μg μl−1) was incubated with MAFP (concentration range given in the figure) in the complete assay buffer with βME described for panel A for 10 min prior to the addition of SOD1 (0.2 μg μl−1) to start the reaction. RP534 activity is expressed as the linear rate determined from a 5-min time course (average for 3 experiments is shown). The asterisk denotes samples in which the inhibition compared to results for the control was statistically significant by a one-tailed t test (P < 0.05).

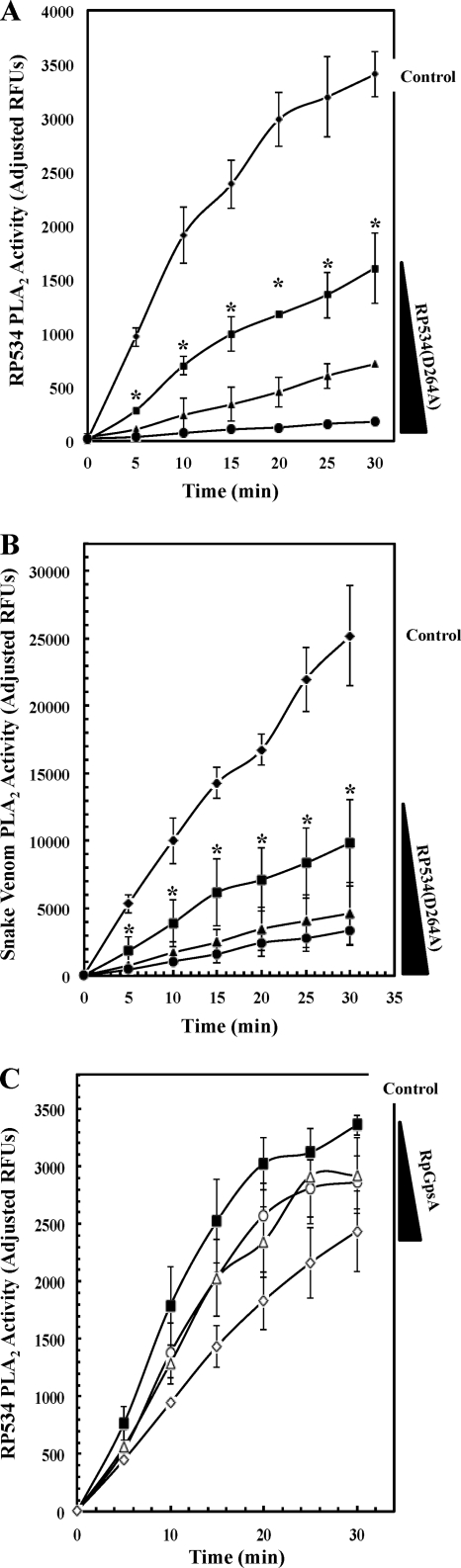

Fig. 4.

(A) The effect of titrated amounts of the N-His10-RP534(D264A) mutant protein as a potential inhibitor of wild-type N-His10-RP534 PLA activity was determined using the PED6 substrate at a final concentration of 2.97 μM. Increasing concentrations of N-His10-RP534(D264A) (0 μg μl−1 [diamonds], 0.01 μg μl−1 [squares], 0.02 μg μl−1 [triangles], and 0.04 μg μl−1 [circles]) were preincubated for 25 min with PED6 prior to the addition of wild-type N-His10-RP534 (at 0.01 μg μl−1) and SOD1 (0.2 μg μl−1) to start the assay. Error bars represent standard errors of the averages from 2 experiments. The asterisk denotes that all samples showed statistically significant inhibition compared to the uninhibited control by a one-tailed t test (P < 0.05). (B) The effect of titrated amounts of the N-His10-RP534(D264A) mutant protein as a potential inhibitor of 0.07 mU μl−1 purified snake venom (Naja mossambica mossambica) PLA2 activity was determined as described for panel A except that SOD1 was omitted from the assay. The asterisk denotes that all samples showed statistically significant inhibition compared to the uninhibited control by a one-tailed t test (P < 0.05). (C) The effect of titrated amounts of the N-His6-GpsA rickettsial protein as a control for nonspecific inhibition of wild-type N-His10-RP534 PLA activity was determined using the PED6 substrate at a final concentration of 2.97 μM. Increasing concentrations of N-His6-GpsA [0 μg μl−1 (filled squares), 0.005 μg μl−1 (open circles), 0.01 μg μl−1 (open triangles), and 0.02 μg μl−1 (open diamonds)] were preincubated for 25 min with PED6 prior to the addition of wild-type N-His10-RP534 (at 0.01 μg μl−1) and SOD1 (0.2 μg μl−1) to start the assay. These N-His6-GpsA protein concentrations were chosen to recapitulate the molar ratios of wild type to mutant RP534 protein used for panel A. Error bars represent standard errors of the averages from 3 experiments. Note that none of the lowest N-His6-GpsA protein concentration data points showed statistically significant inhibition, only 50% of the middle N-His6-GpsA protein concentration data points showed statistically significant inhibition, and all of the highest N-His6-GpsA protein concentration data points showed statistically significant inhibition (P < 0.05 by a one-tailed t test).

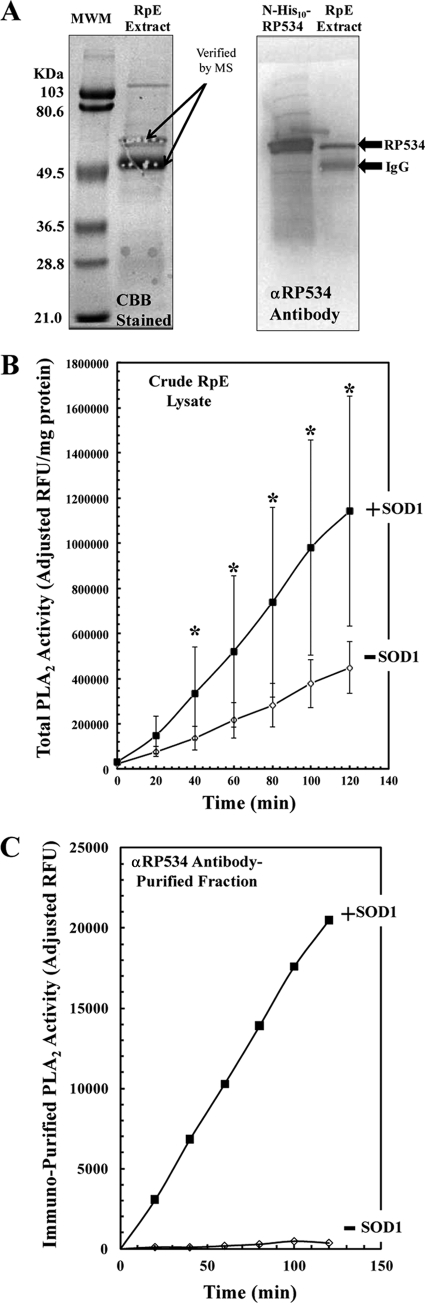

Fig. 5.

Immunoaffinity purification of the wild-type RP534 PLA protein from R. prowazekii lysed cell extracts. (A) Affinity-purified anti-RP534 antibody was used for immunoprecipitation of RP534 from R. prowazekii lysed cell extracts. The elution fraction was resolved by SDS-PAGE, and protein was visualized by Coomassie staining (left panel) and immunoblotting with anti-RP534 antibody (right panel). The identity of RP534 was verified by mass spectrometry. MWM is the molecular size marker in kDa. (B) Total R. prowazekii lysed cell extracts were assayed for SOD1-activated PLA activity (indicative of RP534) using the PED6 substrate and assay buffer described in the legend to Fig. 3A. PLA assays contained 0.02 mg of rickettsial lysate alone (open diamonds) or 0.02 mg of rickettsial lysate with bovine liver SOD1 (0.2 μg μl−1, filled squares). Error bars represent standard errors of the averages from 5 experiments. The asterisks denote samples in which the increase in SOD1-mediated stimulation of PED6 hydrolysis was statistically significant by a one-tailed t test (P < 0.05). (C) The immunoaffinity-purified RP534 protein was assayed for SOD1-activated PLA activity using the PED6 substrate and assay buffer described in the legend to Fig. 3A. Representative results from a single rickettsial preparation are shown using optimal IP conditions. Assays contained 20 μl of the eluted RP534 protein alone (open diamonds) or 20 μl of the eluted RP534 protein with bovine liver SOD1 (0.2 μg μl−1, filled squares).

Immunoprecipitation of active RP534 from lysed cell extracts of purified R. prowazekii.

All experiments described in this article were performed using the Madrid E strain of R. prowazekii (hen egg yolk sac passage 282), purified as previously described (18). For immunoprecipitation (IP) of the RP534 protein from R. prowazekii, purified rickettsiae were washed and suspended in 4 ml of buffer A (135 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 5.4 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM βME, and Roche's EDTA-free complete protease inhibitor cocktail [PIC] [at the manufacturer's suggested concentration], pH 7.4), lysed by ballistic shearing, and cleared of debris (18). R. prowazekii lysed cell extracts (∼5 mg total protein, measured using the Bio-Rad DC protein assay) were incubated with 10 μl protein A Sepharose beads (Pierce) for 10 min at 4°C with agitation followed by incubation with 24 μg of affinity-purified anti-RP534 antibody and 10 μl protein A Sepharose beads for 18 h at 4°C with agitation. The IP samples were washed six times in 0.5 ml of buffer A (no PIC), eluted in 0.2 ml of glycine buffer (0.2 M, pH 2), and neutralized by the addition of 20 μl 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 9.0). Neutralized samples were dried on an Amicon YM-10 ultrafiltration membrane, solubilized in 60 μl Laemmli loading dye (Bio-Rad), and resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% Tris-glycine). Gels were stained with Bio-Rad Biosafe Coomassie, and proteins were excised and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry. Analysis of the RP534 protein by immunoblotting was performed using the protocol described in reference 8. Anti-RP534 rabbit antiserum was used at a 1:500 dilution, peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Sigma) was used at a 1:2,000 dilution, and blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (horseradish peroxidase [HRP] ECL from GE Healthcare), and visualized using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS gel documentation system.

For isolation and assay of RP534 PLA activity from purified R. prowazekii lysed cell extracts (∼2 mg total protein), the IP protocol described above was modified as follows. The protein A preclearing step was performed for 45 min, the affinity-purified anti-RP534 antibody and 10 μl protein A step was performed for 2 h, beads were washed in 0.2 ml of buffer A (no PIC), and protein was eluted in a final volume of 0.25 ml with elution buffer containing 5 mM βME. The IP flowthrough, washes, and eluate were tested for PLA activity using fluorogenic substrates as described above and in the legend to Fig. 5.

RESULTS

In vitro PLA2 activity of purified recombinant RP534 protein.

Considering that the R. prowazekii RP534 open reading frame is a homologue of the P. aeruginosa ExoU PLA2 cytotoxin, we predicted that RP534 would also require the addition of a eukaryotic cofactor(s) to observe PLA activity. Thus, the known activator of P. aeruginosa ExoU, bovine liver SOD1 (35), was specifically tested for activation of RP534 PLA activity in vitro. To this end, a recombinant, N-decahistidine-tagged RP534 protein expressed in E. coli was purified (Fig. 1 A, lane 1) and assayed for PLA activity using LUVs containing [14C]phosphatidylcholine (PC) as a substrate. PC was labeled at the sn-2 position with either [14C]oleic acid (PC-OA) or [14C]arachadonic acid (PC-AA). In these assays, a PLA2 enzyme will produce 14C-labeled free fatty acid, a PLA1 enzyme will produce [14C]lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), and a deacylating enzyme will produce short 14C-labeled fatty acyl chains. RP534 was able to hydrolyze PC-containing LUVs with [14C]sn-2 free fatty acid as the major reaction end product, and unexpectedly, this PLA2 activity was observed in the absence of any eukaryotic cofactors (Fig. 1B, lane 2, and C, open squares and triangles). In the absence of eukaryotic cofactors, RP534 PLA2 activity hydrolyzed ∼80% of the total 14C-labeled free fatty acid over the 30-h time course when PC-OA was presented as a substrate (Fig. 1C, open squares) and ∼35% of the total when PC-AA was the substrate (Fig. 1C, open triangles). We observed a dramatic increase in the reaction rate with both the PC-OA- and PC-AA-containing LUV substrates when RP534 PLA2 activity was assayed in the presence of bovine liver SOD1 (Fig. 1C, compare filled diamonds and circles to open squares and triangles, respectively). Control reactions where the LUV substrates were incubated with SOD1 alone produced negligible amounts of free fatty acid (Fig. 1B, lane 1). Figure 1D shows that SOD1-mediated activation of RP534 PLA2 activity was saturated at an ∼5:1 molar ratio (SOD1/RP534). Intriguingly, we tested SOD1 from other sources, including bacteria, human erythrocyte, and bovine erythrocyte, but none was able to stimulate RP534 activity (data not shown). Our data, along with previous results for P. aeruginosa ExoU (35), suggest that it is not the dismutase enzymatic activity of SOD1 that is affecting RP534 activity in vitro.

We also purified and assayed two other recombinant N-His10-RP534 proteins, each harboring a single alanine substitution at putative active site residue S100 or D264 (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 and 3). These sites were selected based on alignment with P. aeruginosa ExoU and other patatin homologues (36). Figure 1B shows that in either the absence or presence of SOD1, the RP534(S100A) (lanes 3 and 6) and RP534(D264A) (lanes 4 and 7) mutants displayed substantially diminished PLA2 activities.

In vitro PLA1 and lyso-PLA2 activity of purified recombinant RP534 protein.

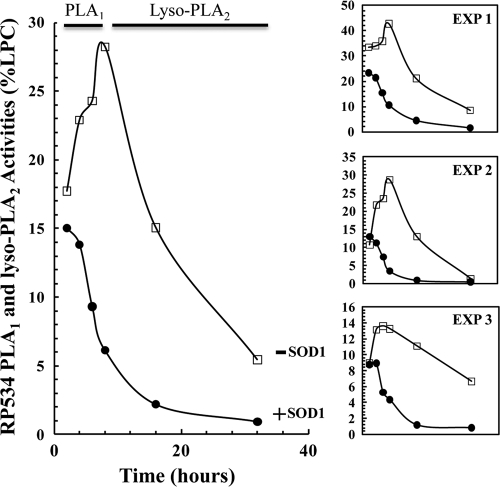

It is known that P. aeruginosa ExoU possesses PLA2 and lyso-PLA activities (42). Our thin-layer chromatographic analysis of the PLA reaction products suggested that RP534 possesses PLA1 and lyso-PLA2 activities in addition to the predominant PLA2 activity. Recall that the [14C]PC substrates are labeled in the sn-2 position, and thus the activity of a PLA1 will produce [14C]LPC and the unlabeled sn-1 free fatty acyl group. Subsequent hydrolysis of the [14C]LPC by a lyso-PLA2 will release [14C]free fatty acid. RP534 PLA reactions run in the absence of SOD1 showed a marked initial increase in the production of [14C]LPC, which is indicative of PLA1 activity. The amount of [14C]LPC then decreased with time, which is indicative of lyso-PLA2 activity (Fig. 2, open squares). Addition of SOD1 to the reaction appeared to ablate the initial increase in [14C]LPC levels, but any existing [14C]LPC was hydrolyzed by the lyso-PLA2 activity (Fig. 2, filled circles). The drop in PLA1 activity may have been due to the rapid depletion of substrate by the SOD1-stimulated PLA2 activity. Alternatively, the addition of SOD1 may downregulate the PLA1 activity. We are currently examining these interesting possibilities. While the overall trends shown in Fig. 2 are strongly suggestive that RP534 possesses PLA1 and lyso-PLA2 activities, we acknowledge that these data did not reach statistical significance when [14C]LPC levels were compared to their starting time point, likely due in part to the observed variability between the three experiments.

Fig. 2.

The N-His10-RP534 PLA1 and lyso-PLA2 activities were measured by expressing the amount of LPC released as a percentage of the total counts in the entire lane by densitometry. N-His10-RP534 (0.01 μg μl−1) was incubated with 0.25 μM PC/PS LUVs ([14C]PC-OA labeled) (open squares) or 0.25 μM PC/PS LUVs ([14C]PC-OA labeled) and bovine liver SOD1 (0.07 μg μl−1) (filled circles). The large panel shows the average, with data for each individual experiment shown to the right.

In vitro PLA1 and PLA2 activities of recombinant RP534 and PaExoU proteins.

Next, we used highly sensitive fluorogenic phospholipid substrates to examine the in vitro PLA1 and PLA2 activities of recombinant RP534 and P. aeruginosa ExoU (PaExoU; also purified as a recombinant protein expressed in E. coli; gel picture not shown). The PED-A1 substrate measures PLA1 activity, and the PED6 substrate has been used previously to measure the PLA2 activity of PaExoU (9, 35). Figure 3 A shows that RP534-mediated hydrolysis of both the PED-A1 and PED6 substrates was dependent on the presence of SOD1 over the time course tested (compare open and filled symbols). These PED-A1 data lend further support to the conclusions drawn from Fig. 2 that RP534 possesses PLA1 activity in vitro. The results presented in Fig. 3B did the following: (i) confirmed that PaExoU-mediated hydrolysis of the PED6 substrate occurred upon the addition of SOD1 (open and filled squares) and (ii) showed that PaExoU was unable to hydrolyze the PED-A1 substrate over the time course tested (open and filled circles). In fact, there was a modest quenching of the PED-A1 fluorescent signal in the presence of PaExoU and SOD1. PaExoU began to show a very modest amount of PED-A1 hydrolysis in the presence of SOD1 after 25 min of incubation, but this observation was not pursued further. As a control, we verified that incubation of either substrate with SOD1 alone showed no PLA activity (data not shown).

As further evidence that RP534 is a bona fide PLA enzyme, we tested its ability to hydrolyze the PED6 substrate in the presence of two known inhibitors of PLA2 activity. Figure 3C shows inhibition of RP534 PLA2 activity by nanomolar amounts of the potent, irreversible inhibitor MAFP (Fig. 3C). The reversible inhibitor AACOCF3 inhibited recombinant RP534 activity at 10 μM (data not shown).

Mechanism of SOD1-stimulated RP534 PLA activity.

The fact that RP534-mediated hydrolysis of the fluorogenic phospholipid substrates was entirely SOD1 dependent over a short time course furnished us with a sensitive assay to examine the mechanism of SOD1-mediated activation. The RP534 interaction with the PED6 substrate was tested using the RP534(D264A) mutant as a potential inhibitor of wild-type RP534 PLA2 activity. We first verified that the RP534(S100A) and RP534(D264A) mutants were unable to hydrolyze the PED6 substrate in the presence or absence of SOD1 (data not shown). For the inhibition experiments, the PED6 substrate was preincubated with increasing amounts of the RP534(D264A) mutant protein for 20 min, followed by the addition of wild-type RP534 and SOD1 to the reaction mixture. Figure 4A shows that the addition of increasing amounts of the RP534(D264A) protein to the reaction mixture resulted in a concomitant reduction in the rate of SOD1-dependent PED6 hydrolysis by wild-type RP534. These data raised the interesting question of whether the RP534(D264A) mutant was sequestering the substrate or specifically forming an inactive complex with the wild-type RP534 protein. Figure 4B shows that preincubation of the PED6 substrate with the RP534(D264A) mutant protein also inhibited the activity of the snake venom PLA2 protein, indicating that the RP534(D264A) mutant protein may be sequestering the PED6 substrate. As a control, we tested a non-PLA rickettsial protein previously characterized by our laboratory (18) to show that the observed RP534(D264A)-mediated inhibition of RP534 PLA2 activity was specific (Fig. 4C). Together these data suggest a mechanism in which RP534 binds to its substrate and the rate of hydrolysis is stimulated upon the addition of SOD1.

The RP534 PLA is assayable in lysed cell extracts of R. prowazekii.

Recombinant N-His10-RP534 protein was used to prepare rabbit polyclonal antiserum to probe whether RP534 is expressed and active in purified R. prowazekii. Figure 5A shows that the RP534 protein was isolated from rickettsial lysed cell extracts by immunoprecipitation, and the identity of the protein was verified by mass spectrometry (MS). These data confirm two previous MS-based proteomic studies that detected RP534 in purified R. prowazekii (12, 43). The crude R. prowazekii lysed cell extracts displayed both SOD1-dependent (Fig. 5B, squares) and SOD1-independent (Fig. 5B, diamonds) PLA2 activities using the PED6 substrate. The observation of SOD1-independent PLA2 activity in R. prowazekii extracts using a fluorescence-based assay was not unexpected in light of a previous report (26). The SOD1-dependent increase in PLA2 activity in the crude extracts (Fig. 5B) was statistically significant compared to results for the unstimulated samples, thus suggesting that the observed increase is due to activation of RP534. The large experimental error observed was likely due to the unavoidable variability inherent in preparations of R. prowazekii isolated from embryonated hen egg yolk sacs.

The RP534 protein was immunoaffinity purified from the R. prowazekii extracts using the anti-RP534 antibody and displayed the expected SOD1-dependent PLA2 activity when assayed using the PED6 substrate (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, shorter incubation times between the anti-RP534 antibody and the R. prowazekii lysed cell extracts yielded protein with higher specific PLA2 activity, whereas overnight incubations resulted in total inactivation of SOD1-stimulated PLA2 activity (data not shown). Together, these data suggest that R. prowazekii synthesizes the RP534 protein and that in lysed cell extracts the protein becomes inactive with time. This observation is extremely interesting considering that purified recombinant N-His10-RP534 purified from E. coli does not lose activity over weeks of storage at 4°C. We are further studying this phenomenon.

DISCUSSION

The present study has shown that purified, recombinant RP534 possesses PLA1, PLA2, and lyso-PLA2 activities and that bovine liver SOD1 can stimulate RP534 activity in vitro. The evidence demonstrating that RP534 is a bona fide PLA protein includes the following: (i) the observation that the recombinant RP534 PLA activities were measurable in the absence of any eukaryotic cofactors (Fig. 1B and C), (ii) the deleterious effect of mutating putative active site residues S100 and D264 on RP534 PLA activity (Fig. 1B), and (iii) the inhibition of RP534 activity by the known PLA2 inhibitors MAFP and AACOCF3 (Fig. 3C and data not shown). The R. prowazekii ExoU homologue also displayed some distinguishing characteristics compared to what has been published for P. aeruginosa ExoU by several independent groups (14, 27, 28, 36, 37, 42, 44). First, our direct comparison of the two enzymes using fluorogenic phospholipid substrates demonstrated that RP534 possessed a distinguishing PLA1 activity. Second, published studies have shown that measurement of PaExoU activity in vitro requires the addition of eukaryotic cofactors. Conversely, we were readily able to measure RP534 PLA activity in the absence of any eukaryotic cofactor(s). Perhaps a recombinant PaExoU protein does not remain stable and active over the extended 30-h time course that was required to observe the near-complete hydrolysis of PC-OA by RP534 in the absence of a eukaryotic cofactor(s). We observed that purified recombinant PaExoU lost activity after storage at 4°C over a shorter period of time than was the case for RP534, although this was not pursued further (data not shown). Interestingly, despite these differences, both PLAs show conservation of their activation by a common eukaryotic cofactor, indicating that mechanisms of activation of the ExoU family of PLAs may be evolutionarily conserved. In addition, the RP534 protein was shown to be expressed in R. prowazekii purified from embryonated hen egg yolk sacs and when purified by immunoprecipitation displayed the expected SOD1-stimulated PLA2 activity when assayed with the sensitive PED6 fluorogenic substrate (Fig. 5). The fact that the RP534 PLA reaction rates were slow compared to those for the snake venom PLA2 controls seems to fit with the obligate intracytoplasmic lifestyle of R. prowazekii, which is typified by slow growth and filling of the host cell cytosol with pathogens prior to lysis and release.

The RP534 PLA demonstrated notable differences in activity depending upon the substrate used in the assay. In the absence of SOD1, the RP534 PLA showed a higher rate of [14C]PC-OA hydrolysis than with [14C]PC-AA when these substrates were presented as PC/PS-mixed LUVs (Fig. 1C). Although the addition of SOD1 to the reaction resulted in similar rates of [14C]PC-OA and [14C]PC-AA hydrolysis, it was apparent that more of the [14C]PC-OA substrate was consumed (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, the PED6 substrate, which is composed of a modified ethanolamine head group and a fluorophore in the sn-2 position, was hydrolyzed by RP534 only in the presence of SOD1 over a short time course (Fig. 3A). Together these data suggest that the fatty acyl group in the sn-2 position and the nature of the polar head group may influence RP534 substrate recognition prior to its activation by SOD1 or any other unknown eukaryotic cofactor(s).

The identification of ExoU homologues in the obligate intracellular pathogenic rickettsiae and the free-living, opportunistic pseudomonad raises interesting questions regarding the ancestral acquisition and evolution of ExoU function in these phylogenetically unrelated organisms. It is postulated that the P. aeruginosa exoU gene was acquired via horizontal transfer, as indicated by its location in the genome and G/C content different from that of the core genome (23). Conversely, the R. prowazekii RP534 gene displays a high A/T content that is a hallmark of the R. prowazekii genome (6), indicating that it was likely acquired by an early ancestor. The homology between the P. aeruginosa ExoU and R. prowazekii RP534 PLAs is limited to the N terminus, which contains the putative PLA catalytic domains. Conversely, their C termini are large domains constituting half of the ∼70-kDa protein sequence but share no identifiable homology. Divergence of their C-terminal domains may have been influenced by the different mechanisms by which these pathogens secrete the protein into the host cell milieu. P. aeruginosa secretes ExoU via the type three secretion system, which is not present in any Rickettsia species genome sequenced to date. The RP534 homologue of Rickettsia typhi has been shown to be released to the host cell cytosol (29), but the underlying mechanism(s) of release remains unknown. Other exciting possibilities inherent in the divergent C-terminal sequences of the RP534 and ExoU PLAs include possible explanations for our observed differences in PLA1 activity and SOD1-mediated activation, possible differences in subcellular targeting/trafficking within the host cell, or differences in their ultimate effect on host cell physiology. Resolution of these questions may provide critical insight into our understanding of rickettsial obligate intracytoplasmic parasitism.

While the pathogenic role of the R. prowazekii ExoU homologue remains unknown, the ExoU homologue of R. typhi (RT0522) has recently been characterized and shown to be present in the host cytosol during infection (29). Similar to P. aeruginosa ExoU, secretion of the rickettsial ExoU PLA homologues would facilitate a perhaps necessary encounter with a eukaryotic activator, such as SOD1, to mediate the desired effects on the host cell. Interestingly, purified recombinant R. typhi RT0522 PLA activity was reported to be dependent upon the presence of eukaryotic cell extracts to stimulate activity in vitro and displayed weaker activity than purified P. aeruginosa ExoU when activity was assayed using a fluorogenic phospholipid substrate (29). In our assay system using fluorogenic substrates, the purified R. prowazekii RP534 PLA had considerably greater PLA activity than purified recombinant P. aeruginosa ExoU (Fig. 3A and B) and that reported for R. typhi RT0522 (29). Considering that the R. prowazekii and R. typhi ExoU homologues share >90% identity, it will be important to resolve these apparent discrepancies by assaying R. typhi ExoU activity using the radiolabeled PC substrates employed in our study. Any similarities and/or differences might reflect differences in the virulence of these two rickettsial pathogens.

Analyses of all sequenced rickettsial genomes reveal an intriguing difference with respect to the status of ExoU homologues. Functional ExoU homologues are present in the typhus group rickettsiae, R. prowazekii (RP534 from this study) and R. typhi (RT0522 from reference 29), and rickettsial ExoU homologues also appear to be intact in the distant relatives Rickettsia massiliae and Rickettsia bellii (84% and 69% identity, respectively, with perfect conservation of putative active site residues, but their biochemical properties are unknown). Intriguingly, rickettsial ExoU homologues in all other sequenced rickettsial genomes, including the spotted fever group (e.g., Rickettsia rickettsii and Rickettsia conorii), are markedly degenerated/fragmented and may no longer be functional. These genomic analyses may shed light on previous studies implicating PLA2 as critical to the interaction of both typhus group and spotted fever group rickettsiae with eukaryotic host cells (39, 46, 51, 54, 56). Homologues of RP602, the other rickettsial patatin-like PLA, have been identified in all sequenced rickettsial genomes to date. Interestingly, Rickettsia felis possesses two additional plasmid-borne gene copies (10). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that RP602 is a major player in rickettsia-host interactions and that the ExoU homologues have been maintained to play either a redundant or an evolved specialized role in the typhus group rickettsiae and possibly in R. massiliae and R. bellii. Alternatively, rickettsial ExoU homologues may be entirely dispensable and will eventually be lost from the core genome. In either case, one must be cautious in making such assertions until the biological role of RP602 homologues is fully established and the existing ExoU gene fragments from the spotted fever group rickettsiae are examined for any remaining activity or function. Our current focus is on investigating the role of RP534 PLA activity in R. prowazekii growth and pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dara Frank and Hiromi Sato for helpful discussions and for assistance in developing the isotopic PLA assay. Thanks go to D. Frank for critical reading of the manuscript. Expert technical assistance was provided by Robin Daugherty, Ting-Jia Fan, and Ching-Yao Yang. Additional thanks go to David O. Wood and John W. Foster for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI-15035, AI-15035-S1, and AI085002 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the NIAID or NIH.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 July 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allewelt M., Coleman F. T., Grout M., Priebe G. P., Pier G. B. 2000. Acquisition of expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU cytotoxin leads to increased bacterial virulence in a murine model of acute pneumonia and systemic spread. Infect. Immun. 68:3998–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Altschul S. F., et al. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson B., Friedman H., Bendinelli M. 1997. Rickettsial infection and immunity. Plenum Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andersson J. O., Andersson S. G. E. 2000. A century of typhus, lice and Rickettsia. Res. Microbiol. 151:143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andersson S. G. E., et al. 1998. The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature 396:133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andrews D. L., Beames B., Summers M. D., Park W. D. 1988. Characterization of the lipid acyl hydrolase activity of the major potato (Solanum tuberosum) tuber protein, patatin, by cloning and abundant expression in a baculovirus vector. Biochem. J. 252:199–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Audia J. P., Foster J. W. 2003. Acid shock accumulation of sigma S in Salmonella enterica involves increased translation, not regulated degradation. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 5:17–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Benson M. A., Schmalzer K. M., Frank D. W. 2010. A sensitive fluorescence-based assay for the detection of ExoU-mediated PLA(2) activity. Clin. Chim. Acta 411:190–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blanc G., Renesto P., Raoult D. 2005. Phylogenic analysis of rickettsial patatin-like protein with conserved phospholipase A2 active sites. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1063:83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37:911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chao C. C., Chelius D., Zhang T., Daggle L., Ching W. M. 2004. Proteome analysis of Madrid E strain of Rickettsia prowazekii. Proteomics 4:1280–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clarke D. H., Fox J. P. 1948. The phenomenon of in vitro hemolysis produced by the rickettsiae of typhus fever, with a note on the mechanism of rickettsial toxicity in mice. J. Exp. Med. 88:25–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Finck-Barbancon V., Frank D. W. 2001. Multiple domains are required for the toxic activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU. J. Bacteriol. 183:4330–4344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Finck-Barbancon V., et al. 1997. ExoU expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa correlates with acute cytotoxicity and epithelial injury. Mol. Microbiol. 25:547–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fine J. B., Sprecher H. 1982. Unidimensional thin-layer chromatography of phospholipids on boric acid-impregnated plates. J. Lipid Res. 23:660–663 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Frank D. W. 1997. The exoenzyme S regulon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 26:621–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Frohlich K. M., Roberts R. A., Housley N. A., Audia J. P. 2010. Rickettsia prowazekii uses an sn-glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and a novel dihydroxyacetone phosphate transport system to supply triose phosphate for phospholipid biosynthesis. J. Bacteriol. 192:4281–4288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghosh M., Tucker D. E., Burchett S. A., Leslie C. C. 2006. Properties of the group IV phospholipase A2 family. Prog. Lipid. Res. 45:487–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hackstadt T. 1996. The biology of Rickettsiae. Infect. Agents Dis. 5:127–143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirschberg H. J., Simons J. W., Dekker N., Egmond M. R. 2001. Cloning, expression, purification and characterization of patatin, a novel phospholipase A. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:5037–5044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kolarovic L., Fournier N. C. 1986. A comparison of extraction methods for the isolation of phospholipids from biological sources. Anal. Biochem. 156:244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kulasekara B. R., et al. 2006. Acquisition and evolution of the exoU locus in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 188:4037–4050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miroux B., Walker J. E. 1996. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J. Mol. Biol. 260:289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Netesov S. V., Conrad J. L. 2001. Emerging infectious diseases in Russia, 1990-1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ojcius D. M., Thibon M., Mounier C., Dautry-Varsat A. 1995. pH and calcium dependence of hemolysis due to Rickettsia prowazekii: comparison with phospholipase activity. Infect. Immun. 63:3069–3072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Phillips R. M., Six D. A., Dennis E. A., Ghosh P. 2003. In vivo phospholipase activity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa cytotoxin ExoU and protection of mammalian cells with phospholipase A2 inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 278:41326–41332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rabin S. D., Hauser A. R. 2003. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU, a toxin transported by the type III secretion system, kills Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Infect. Immun. 71:4144–4150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rahman M. S., Ammerman N. C., Sears K. T., Ceraul S. M., Azad A. F. 2010. Functional characterization of a phospholipase A(2) homolog from Rickettsia typhi. J. Bacteriol. 192:3294–3303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ramm L. E., Winkler H. H. 1976. Identification of cholesterol in the receptor site for rickettsiae on sheep erythrocyte membranes. Infect. Immun. 13:120–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ramm L. E., Winkler H. H. 1973. Rickettsial hemolysis: adsorption of rickettsiae to erythrocytes. Infect. Immun. 7:93–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramm L. E., Winkler H. H. 1973. Rickettsial hemolysis: effect of metabolic inhibitors upon hemolysis and adsorption. Infect. Immun. 7:550–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Raoult D., et al. 1998. Outbreak of epidemic typhus associated with trench fever in Burundi. Lancet 352:353–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rydel T. J., et al. 2003. The crystal structure, mutagenesis, and activity studies reveal that patatin is a lipid acyl hydrolase with a Ser-Asp catalytic dyad. Biochemistry 42:6696–6708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sato H., Feix J. B., Frank D. W. 2006. Identification of superoxide dismutase as a cofactor for the pseudomonas type III toxin, ExoU. Biochemistry 45:10368–10375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sato H., Frank D. W. 2004. ExoU is a potent intracellular phospholipase. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1279–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sato H., et al. 2003. The mechanism of action of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa-encoded type III cytotoxin, ExoU. EMBO J. 22:2959–2969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schulert G. S., et al. 2003. Secretion of the toxin ExoU is a marker for highly virulent Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates obtained from patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 188:1695–1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Silverman D. J., Santucci L. A., Meyers N., Sekeyova Z. 1992. Penetration of host cells by Rickettsia rickettsii appears to be mediated by a phospholipase of rickettsial origin. Infect. Immun. 60:2733–2740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Snyder J. C., Bovarnick M. R., Miller J. C., Chang S.-M. 1954. Observations on the hemolytic properties of typhus rickettsiae. J. Bacteriol. 67:724–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Strickland J. A., Orr G. L., Walsh T. A. 1995. Inhibition of Diabrotica larval growth by patatin, the lipid acyl hydrolase from potato tubers. Plant Physiol. 109:667–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tamura M., et al. 2004. Lysophospholipase A activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III secretory toxin ExoU. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 316:323–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tucker A. M., Pannell L. K., Wood D. O. 2005. Dissecting the Rickettsia prowazekii genome: genetic and proteomic approaches. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1063:35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vallis A. J., Finck-Barbancon V., Yahr T. L., Frank D. W. 1999. Biological effects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III-secreted proteins on CHO cells. Infect. Immun. 67:2040–2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Walker D. H. (ed.) 1988. Biology of rickettsial diseases, vol. II CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 46. Walker D. H., Feng H.-M., Popov V. L. 2001. Rickettsial phospholipase A2 as a pathogenic mechanism in a model of cell injury by typhus and spotted fever group rickettsiae. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65:936–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Weiss E. 1982. The biology of rickettsiae. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 36:345–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Winkler H. H. 1974. Inhibitory and restorative effects of adenine nucleotides on rickettsial adsorption and hemolysis. Infect. Immun. 9:119–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Winkler H. H. 1990. Rickettsia species (as organisms). Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 44:131–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Winkler H. H. 1977. Rickettsial hemolysis: adsorption, desorption, readsorption, and hemagglutination. Infect. Immun. 17:607–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Winkler H. H., Daugherty R. M. 1989. Phospholipase A activity associated with the growth of Rickettsia prowazekii in L929 cells. Infect. Immun. 57:36–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Winkler H. H., Day L. C., Daugherty R. M. 1994. Analysis of the hydrolytic products from choline labeled host cell phospholipids during the growth of Rickettsia prowazekii. Infect. Immun. 62:1457–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Winkler H. H., Day L. C., Daugherty R. M., Turco J. 1993. Effect of gamma interferon on phospholipid hydrolysis and fatty acid incorporation in L929 cells infected with Rickettsia prowazekii. Infect. Immun. 61:3412–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Winkler H. H., Miller E. T. 1981. Immediate cytotoxicity and phospholipase A: the role of phospholipase A in the interaction of R. prowazekii and L-cells, p. 327–333 In Burgdorfer W., Anacker R. (ed.), Rickettsiae and rickettsial diseases. Academic Press, Inc., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 55. Winkler H. H., Miller E. T. 1980. Phospholipase A activity in the hemolysis of sheep and human erythrocytes by Rickettsia prowazeki. Infect. Immun. 29:316–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Winkler H. H., Miller E. T. 1982. Phospholipase A and the interaction of Rickettsia prowazekii and mouse fibroblasts (L-929 cells). Infect. Immun. 38:109–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Winkler H. H., Ramm L. E. 1975. Adsorption of typhus rickettsiae to ghosts of sheep erythrocytes. Infect. Immun. 11:1244–1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]