Abstract

SHIP is an inositol 5′ phosphatase that hydrolyzes the PI3′K product PI(3,4,5)P3. We show that SHIP-deficient mice exhibit dramatic chronic hyperplasia of myeloid cells resulting in splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and myeloid infiltration of vital organs. Neutrophils and bone marrow-derived mast cells from SHIP−/− mice are less susceptible to programmed cell death induced by various apoptotic stimuli or by growth factor withdrawal. Engagement of IL3-R and GM–CSF-R in these cells leads to increased and prolonged PI3′K-dependent PI(3,4,5)P3 accumulation and PKB activation. These data indicate that SHIP is a negative regulator of growth factor-mediated PKB activation and myeloid cell survival.

Keywords: SHIP, inositol phosphatase, PKB/Akt, cell survival, myeloid cells

The SH2-containing inositol 5-phosphatase (SHIP) is widely expressed in hematopoietic cells. It has been identified as a crucial negative regulator of B-cell activation (Ono et al. 1997; Liu et al. 1998a) and IgE-mediated mast cell degranulation (Huber et al. 1998). SHIP contains an SH2 domain, three putative SH3-interacting motifs, and two potential PTB domain binding sites, allowing it to interact with membrane receptors (Ono et al. 1996; Kimura et al. 1997), tyrosine kinases (Crowley et al. 1996), and adapter proteins (Damen et al. 1993; Lioubin et al. 1994). SHIP hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-polyphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3] and inositol-1,3,4,5-polyphosphate (IP4) to generate phosphatidylinositol-3,4-polyphosphate [PI(3,4)P2] and inositol-1,3,4-polyphosphate (Damen et al. 1996; Lioubin et al. 1996). Because phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3′K) phosphorylates the D3 position of the inositol ring of phosphoinositides to generate phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate, PI(3,4)P2, and PI(3,4,5)P3 (Franke et al. 1997), it has been suggested that SHIP exerts its catalytic activity on phosphoinositides downstream of PI3′K activation.

PI3′K and phospholipid-regulated signaling have been implicated in many cellular functions including cell adhesion, cytoskeletal reorganization, proliferation, and cell survival. In particular, PI3′K and phospholipid-dependent activation of the serine/threonine protein kinase B (PKB, also known as Akt) have been shown to rescue cells from apoptosis and therefore may have a role in tumorigenesis (Hemmings 1997). PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 bind with high affinity to the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain of PKB (Klippel et al. 1997), resulting in the recruitment of PKB to the plasma membrane. PKB then undergoes a conformational change and becomes phosphorylated on Ser-473 and Thr-308 via PDK2/ILK (3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 2/integrin-linked kinase) and PDK1, respectively (Alessi et al. 1997; Delcommenne et al. 1998), two PI3′K-dependent serine/threonine kinases. The tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on cromosome 10) was identified as an inositol polyphosphate 3-phosphatase (Maehama and Dixon 1998), and cells from PTEN-deficient mice exhibit constitutive PKB activity and partial resistance to several apoptotic stimuli (Stambolic et al. 1998). These data suggest that the 3′ phospholipid phosphatase activity of PTEN regulates apoptotic susceptibility by down-regulating PKB activity. However, experiments on PTEN−/− cells showed that only basal PKB activity is regulated in this way; PTEN does not appear to regulate PKB activation following growth factor stimulation (Myers et al. 1998). Thus, other inositol phosphatases responsive to the stimulation of growth factor receptors may exist to regulate PKB activation. A candidate for such a role is SHIP.

To investigate the function of SHIP in vivo, we generated SHIP-deficient mice. We show that mice lacking SHIP display dramatic hyperplasia of myeloid cells in the bone marrow and spleen, and myeloid infiltration in various organs. SHIP−/− myeloid cells are less susceptible to death stimuli and growth factor withdrawal, and exhibit increased and prolonged levels of PKB activation following cytokine stimulation. These data show that SHIP has a pivotal role in down-regulating PKB activity and is a crucial regulator of cell survival and homeostasis.

Results and Discussion

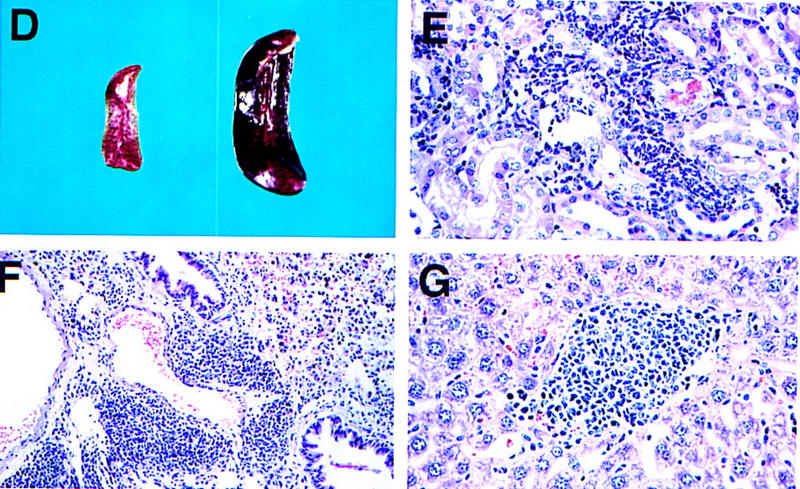

Generation of SHIP-deficient mice

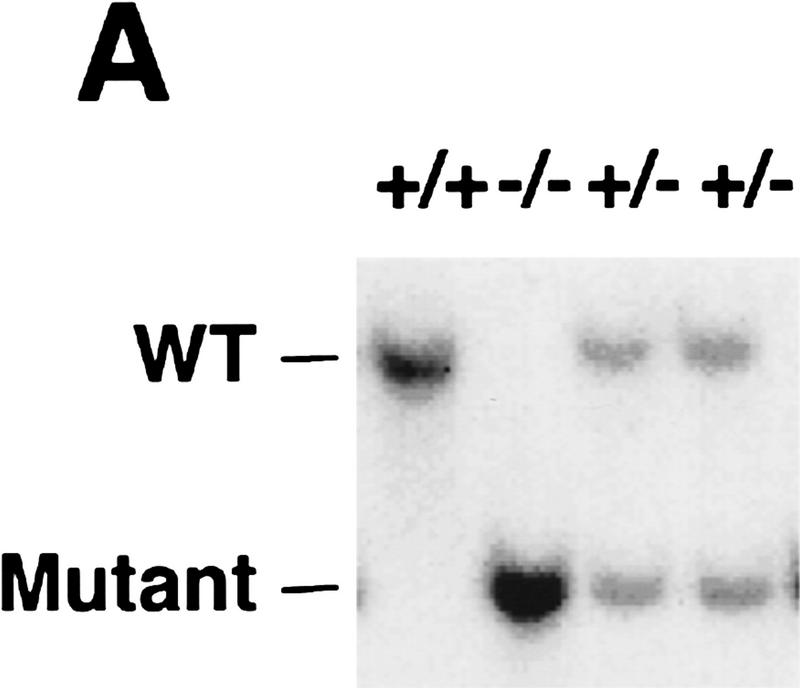

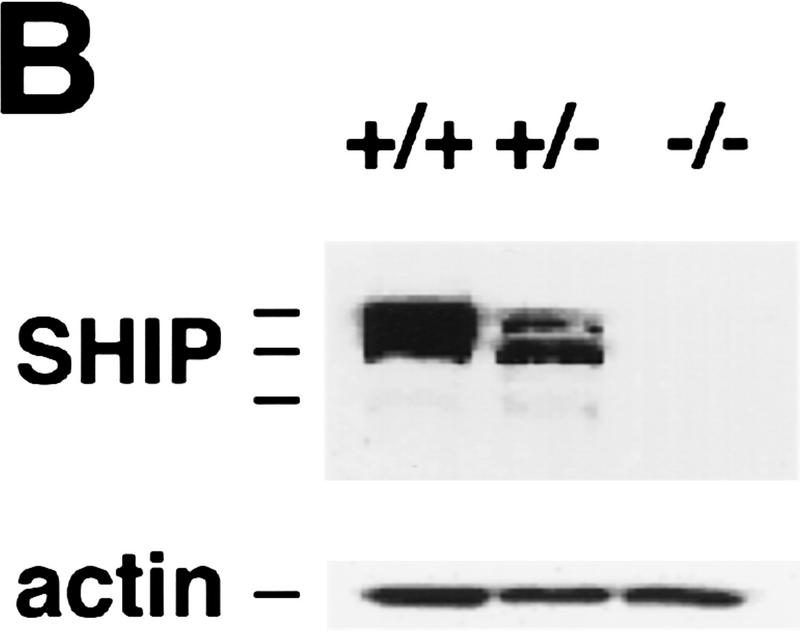

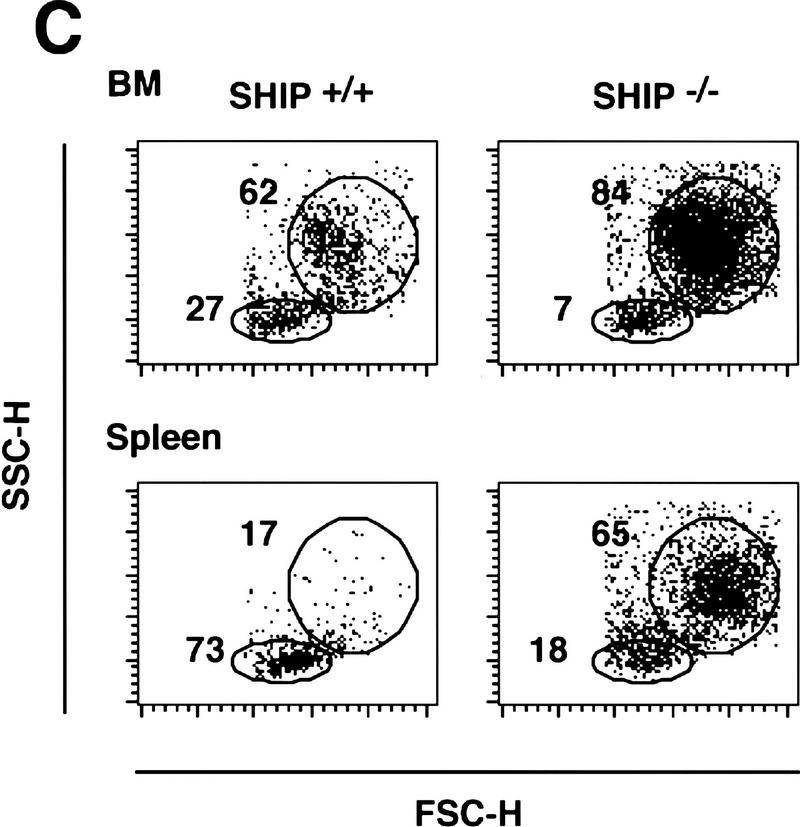

To determine the function of the 5′ lipid phosphatase SHIP in vivo, we generated SHIP-deficient mice via homologous recombination. Southern (Fig. 1A) and Western (Fig. 1B) blot analyses confirmed disruption of the gene and lack of SHIP expression. Homozygous SHIP−/− mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratio. The large majority (>90%) of SHIP−/− mice grew normally and were fertile, albeit with a shortened life span. SHIP−/− mice exhibited enormously enlarged spleens and lymph nodes compared to control littermates (Fig. 1D; data not shown; similar results were reported by Helgason et al. 1998). The size difference of the spleen of SHIP−/− and a control littermate was already apparent at 4 weeks of age. This difference averaged 4-fold at 6–8 weeks, 8-fold at 10 weeks, and >10-fold at 16 weeks after birth. Histological and flow cytometric studies showed that there was a substantial increase in granulocyte–macrophage (GM)/monocyte populations in the bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes of SHIP−/− mice (Fig. 1C; data not shown). SHIP−/− mice exhibited a marked decrease in B220+CD19+sIgM+ B cells in the bone marrow, and reduced numbers of sIgD+sIgM+ mature B cells in secondary lymphatic organs. The ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ T cells appeared normal. Thymus, lymph nodes, liver, kidney, heart, skeletal muscle, connective tissues, exocrine pancreas, and lung of SHIP−/− mice showed infiltration of cells with typical monocyte/macrophage and granulocyte morphologies (Fig. 1E–G; data not shown). Thus, SHIP−/− mice develop progressive myeloid hyperplasia leading to splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and myeloid infiltration of vital organs. These results indicate that SHIP expression is required to maintain homeostasis of myeloid cells in vivo.

Figure 1.

SHIP-deficient mice develop chronic progressive myeloid hyperplasia. (A) Southern blot showing the genotypes of ship+/+, ship+/−, and ship−/− mice. Genomic DNA was digested with EcoRV and hybridized to the 5′ internal probe to visualize a 10.5-kb band for the wild-type allele and a 5.8-kb band for the mutant allele. (B) Western blot of BMMC lysates showing the level of SHIP proteins in wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and homozygous (−/−) SHIP mutant mice. Blots of total protein extracts from 1 × 106 BMMCs were incubated with anti-SHIP antibody. The positions of the multiple forms of SHIP are indicated. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with an anti-actin antibody to control for equal loading. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of total splenocyte and bone marrow populations in 8-week-old SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− littermates. Percentages of large cells (monocyte and granulocyte populations) and small cells (predominantly lymphocytes) as defined by forward-scatter (FSC-H) vs. side-scatter (SSC-H) parameters are indicated. One result is representative of 10 independent experiments. (D) Comparison of the size of spleens from 8-week-old wild-type (left) and SHIP−/− (right) mice. (E–G) Myeloid infiltration into the kidney (E), lung (F), and liver (G) of a SHIP−/− mouse. Every mutant mouse analyzed (>10 mice) showed infiltration of myeloid cells into these organs. The extent of infiltration increased with the age of the mice. The presence of macrophages/monocytes in C and E–G was confirmed using antibodies specific for markers of monocytes/macrophages (CD11b+) and granulocytes (Gr1+). H&E staining. Magnifications, 120× (E,G) and 40× (F).

SHIP−/− myeloid cells exhibit decreased susceptibility to apoptotic death

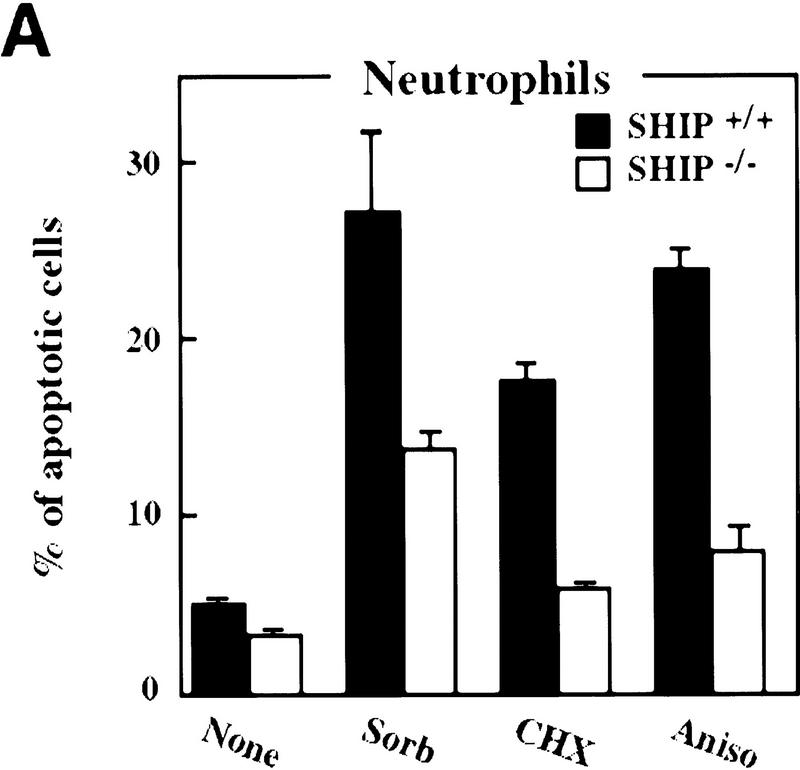

It has been suggested that SHIP can function as a negative regulator of cell growth (Lioubin et al. 1996; Liu et al. 1998a) and/or a positive factor in cellular apoptosis (Liu et al. 1997). Because neutrophils in peripheral lymphoid organs do not proliferate and have very short life spans (Raff 1998), we analyzed the survival of freshly isolated neutrophils in the absence of SHIP. Compared to SHIP-expressing neutrophils, freshly isolated neutrophils from SHIP−/− mice exhibited enhanced resistance to apoptosis induced by osmotic shock (sorbitol), protein synthesis inhibitors (cycloheximide, anisomycin), heat shock, and serum withdrawal (Fig. 2A; not shown).

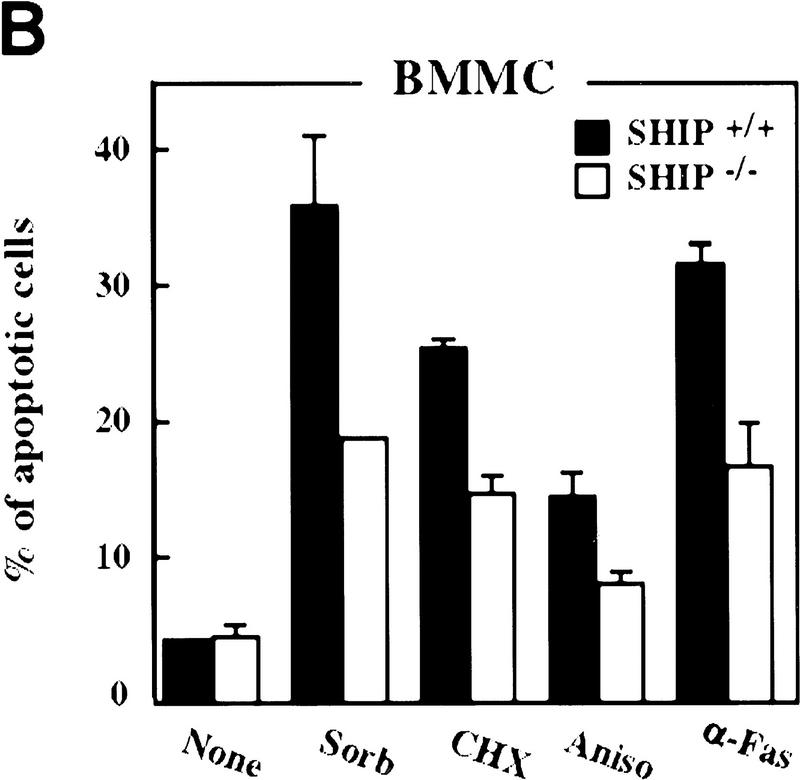

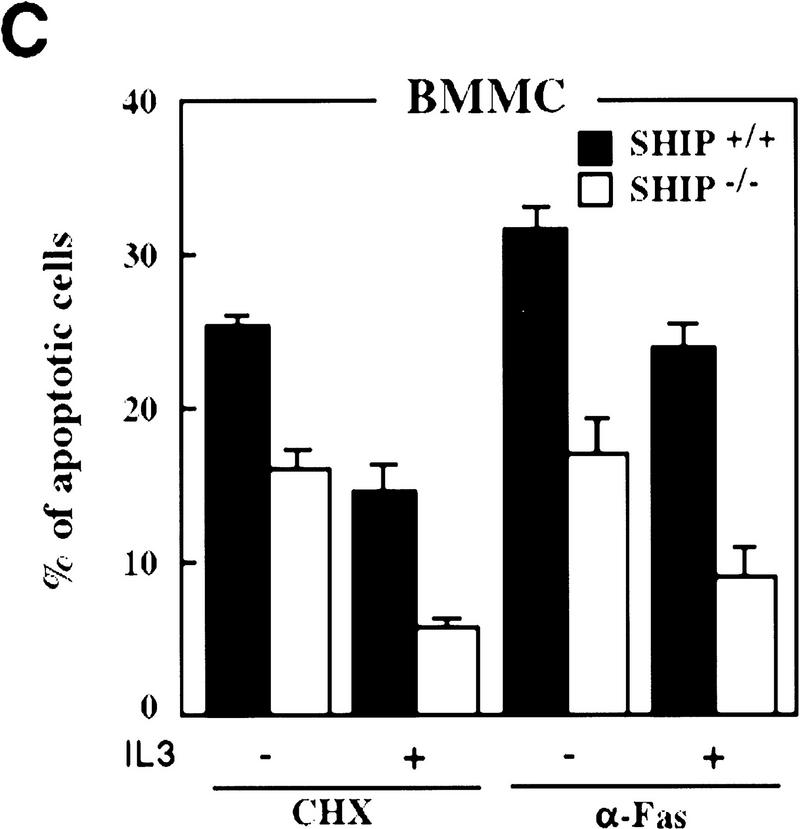

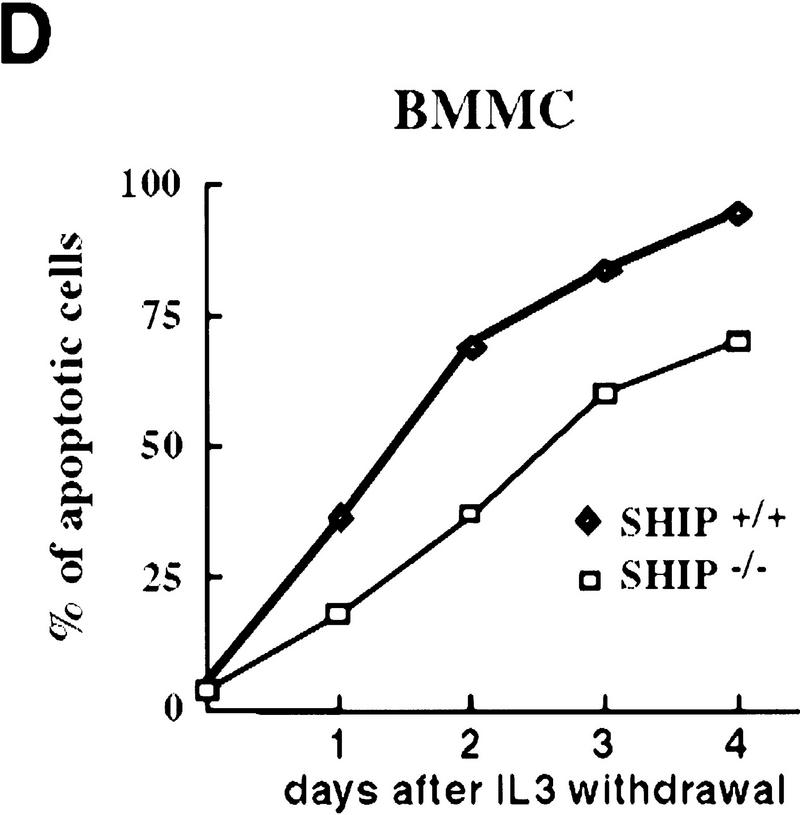

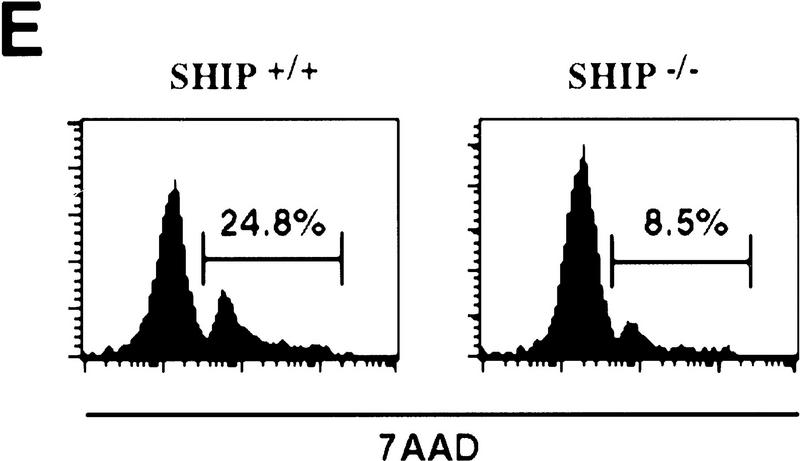

Figure 2.

Decreased sensitivity of SHIP-deficient myeloid cells to apoptotic stimuli. Freshly isolated neutrophils (A)and BMMCs derived from SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− mice (B) were incubated with PBS (none); 400 mm sorbitol (Sorb), 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX), 2 μg/ml anisomycin (Aniso), or 2 μg/ml anti-Fas antibody (α-Fas) as indicated. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined 24 hr after death using 7AAD. (C) IL3 increases the survival of SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− BMMCs. BMMCs were incubated with or without IL3 in the presence of the indicated apoptotic stimuli. Percentages of apoptotic cells were determined 24 hr after induction. Genotypes of cells are indicated. Percentages of apoptotic cells were determined by staining with 7AAD. (A–C) are representative of at least five independent experiments. Percentages of survival and mean values of triplicate cultures ± s.e.m. are shown. (D) IL3-dependent BMMCs from SHIP−/− mice show higher viability following IL3 withdrawal. IL3 was removed and BMMCs were incubated in 2% FBS. The viability of cells was monitored for 4 days using 7AAD staining. One experiment is representative of five independent experiments. (E) Representative flow cytometric analysis showing the percentages of 7AAD-positive apoptotic cells in SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− BMMCs 24 hr after IL3 withdrawal as in D.

To further elucidate the role of SHIP in myeloid cell survival in a defined cell population, we established bone marrow-derived mast cell lines (BMMCs) from SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− mice. IL3-BMMC, driven proliferation and cell surface expression of IL3-R, c-Kit and the death receptor Fas were comparable between SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− BMMCs (not shown). SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− BMMCs produced comparable levels of endogenous interleukin-3 (IL3) as determined by ELISA (not shown). All SHIP−/− mast cell lines tested displayed enhanced resistance to apoptosis induced by sorbitol, cycloheximide, anisomycin, and Fas stimulation (Fig. 2B). SHIP−/− mast cells also displayed enhanced viability following IL3 withdrawal (Fig. 2D,E). Similar to GM–CSF (colony stimulation factor) stimulation of neutrophils, addition of IL3 reduced the susceptibility to apoptotic stimuli of both SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− BMMCs (Fig. 2C). These results show that the absence of SHIP expression renders myeloid cells, that is, BMMCs and freshly isolated neutrophils, partially resistant to apoptosis induced by a variety of apoptotic stimuli, an effect that can be enhanced by the presence of growth factors. Thus, a survival signal exists that is both responsive to growth factor stimulation and negatively regulated by SHIP.

SHIP regulates growth factor receptor-mediated PKB activity

IL3-R, GM-CSF-R, and IL5-R share a common β-chain (βc), which is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues upon ligand stimulation (Miyajima et al. 1993). Phosphorylation of the βc chain triggers activation of the MAPK, Jak2/Stat5, and PI3′K signaling pathways. Activation of the Jak/Stat pathway is required for the induction of DNA synthesis and cell proliferation, whereas PI3′K activation predominantly mediates cell survival (deGroot et al. 1998). It has been shown that PKB acts downstream of PI3′K and overexpression of PKB partially protects cells from apoptosis induced by growth factor withdrawal or PI3′K inhibition (Franke et al. 1997; Downward 1998).

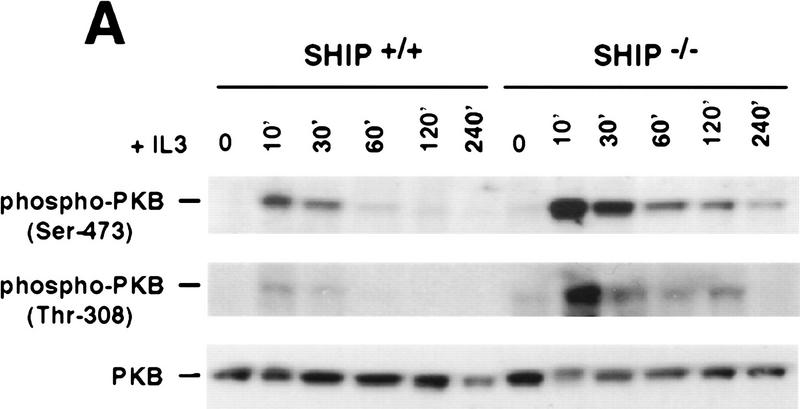

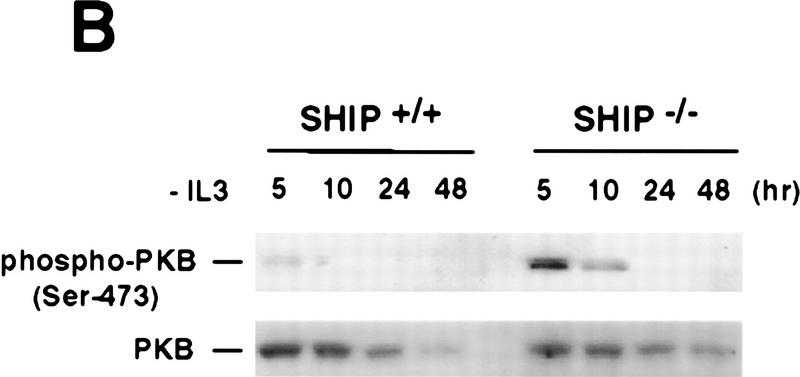

To elucidate the role of SHIP in IL3-R signaling, we analyzed MAPK, Stat5, and PKB activation in SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− BMMC following IL3 stimulation. PKB activation and phosphorylation of PKB on Ser-473 and Thr-308 (Fig. 3A) were dramatically enhanced and prolonged in the absence of SHIP. The extent of MAPK and Stat5 phosphorylation and overall tyrosine phosphorylation in response to various concentrations of IL3 (0.1, 0.5, 2, and 5 ng/ml) were comparable among SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− BMMC (not shown), suggesting that SHIP has a predominant role in PKB activation downstream of the IL3-R. In addition, GSK3, the downstream target of PKB, was hyperphosphorylated in IL3-stimulated SHIP−/− BMMCs (not shown), indicating that enhanced PKB phosphorylation leads to the increased phosphorylation and activation of cellular targets of PKB. Similarly, freshly isolated neutrophils from SHIP−/− mice exhibited enhanced and prolonged PKB phosphorylation in response to GM–CSF (not shown). Whereas IL3 removal from cultures of SHIP+/+ BMMC leads to rapid inactivation of PKB (dephosphorylation of Ser-473), residual PKB phosphorylation was observed in SHIP−/− cells even 10 hr after IL3 withdrawal (Fig. 3B). Enhanced basal levels of PKB phosphorylation were also detected in lysates of freshly isolated SHIP−/− neutrophils, total spleen cells, and bone marrow cells (not shown) suggesting that the PKB signaling pathway is hyperactivated in SHIP−/− mice in vivo.

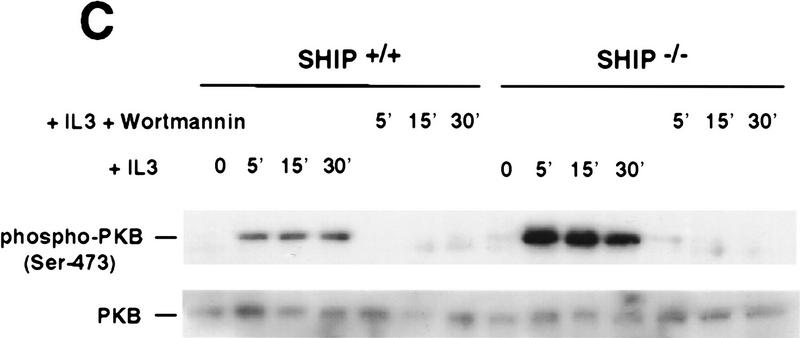

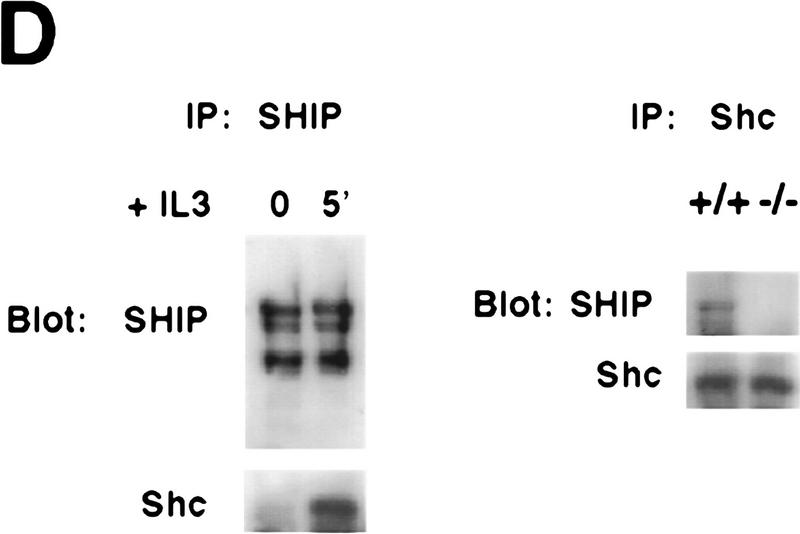

Figure 3.

Negative regulation of PKB phosphorylation by SHIP. (A) Increased PKB phosphorylation in SHIP-deficient BMMCs following stimulation with IL3. Because SHIP−/− BMMCs have elevated baseline levels of activated PKB, cells were starved of IL3 for 24 hr prior to induction. At this time point, no PKB phosphorylation was detectable in SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− cells. Serum-starved BMMCs were stimulated with 5 ng/ml IL3 for the indicated time periods. Total cell lysates were analyzed for activated PKB by Western blot using antibodies specific for Ser-473 (top), or Thr-308 (middle), and total PKB protein (bottom). The middle panel was from a different gel in which the same cell extracts were loaded and equal loading was confirmed by PKB levels (not shown). (B) Prolonged and increased PKB phosphorylation (Ser-473) in SHIP-deficient BMMCs following IL3 withdrawal. Time points after IL3 withdrawal are indicated. Note the enhanced baseline of PKB phosphorylation in SHIP−/− BMMCs at 5 hr after IL3 starvation. This level of phospho-Ser-473 is similar to that in SHIP+/+ BMMCs cultured in IL3 (not shown). (A,B) One result is representative of five experiments. (C) SHIP-regulated PKB activation is PI3′K-dependent. Western blot analysis of cell lysates from serum-starved (A) SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− BMMCs treated with IL3 (5 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of Wortmannin (100 nm) for the indicated time periods. (D) SHIP associates with Shc following IL3 stimulation. Serum-starved SHIP+/+ mast cells were stimulated with IL3 (5 ng/ml) for various time periods. SHIP and Shc were immunoprecipitated independently and interactions between SHIP and Shc visualized by Western blot. (C,D) One result is representative of three independent experiments.

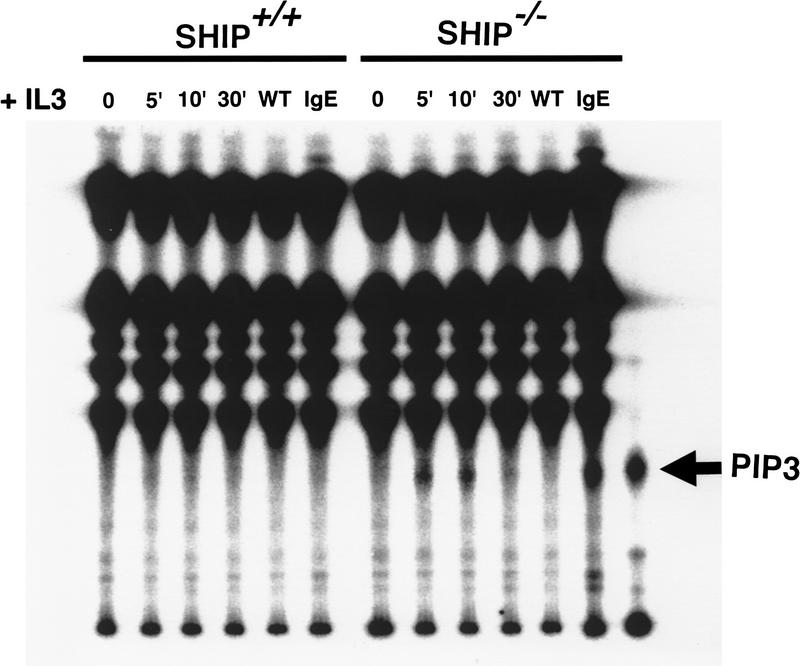

To test whether SHIP-regulated PKB activation depends on PI3′K, serum-starved SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− BMMCs were pretreated with the PI3′K inhibitors wortmannin (Fig. 3C) or LY294002 (not shown). Inhibition of PI3′K activity completely abrogated phosphorylation of PKB in both SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− BMMCs. Moreover, wortmannin-mediated inhibition of PI3′K sensitized SHIP−/− cells to Sorbitol- and cycloheximide-induced apoptosis (not shown). Thus, the enhanced resistance to apoptosis and hyperactivated state of PKB observed in SHIP−/− cells are critically dependent on PI3′K. Because total activity of PI3′K were comparable in SHIP+/+ and SHIP−/− BMMCs (not shown), we investigated whether levels of the PI3′K product PI(3,4,5)P3 were affected. In serum-starved SHIP−/− BMMC, PI(3,4,5)P3 levels were significantly increased by IL3 stimulation (Fig. 4) indicating that PI(3,4,5)P3 is a substrate of SHIP in vivo.

Figure 4.

Increased intracellular levels of PI(3,4,5)P3 in SHIP−/− BMMCs following IL3 stimulation. (WT) 100 nm Wortmannin was added immediately prior to IL3 stimulation, and IL3 stimulation was quenched 10 min later. (IgE) Cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml IgE for 5 min. The position of PI(3,4,5)P3 is indicated as PIP3. One result is representative of three independent experiments is shown.

To determine whether SHIP is recruited to the membrane following IL3 stimulation, BMMCs were stimulated with IL3 for various time periods, and SHIP, Shc, and the βc chain were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates. Although direct interaction between SHIP and the βc chain was not detected, SHIP was found to be tyrosine-phosphorylated and associated with Shc (Src homology and collagen) (Fig. 3D; data not shown), suggesting that, at least in BMMCs, SHIP can be recruited to the membrane upon IL3 stimulation through interaction with Shc. Shc has been identified as an adapter linking growth factor receptor stimulation to activation of the Ras signaling cascade (Rozakis-Adcock et al. 1992). Because MAPK activation appears to be normal in SHIP−/− mast cells, our results imply that the Shc–SHIP association may be relevant to additional functions of Shc in cell survival.

This study shows that SHIP is a crucial negative regulator controlling growth factor receptor-mediated PKB activation and survival of myeloid cells. Engagement of cytokine receptors in myeloid cells not only promotes PI3′K activation, which leads to the production of PI(3,4,5)P3, but also induces the tyrosine phosphorylation of SHIP. Tyrosine-phosphorylated SHIP is then recruited to the membrane, where it dephosphorylates PI(3,4,5)P3 to generate PI(3,4)P2. In the absence of SHIP, PI(3,4,5)P3 levels and PKB activity were significantly elevated. SHIP-regulated PKB activation and the resistance of SHIP-deficient myeloid cells to multiple apoptotic death signals may account for the progressive chronic myeloid hyperplasia seen in SHIP−/− mice in vivo.

Recent experiments have shown that fibroblasts lacking the 3′ inositol phosphatase PTEN exhibit constitutive PKB activity, and mice heterozygous for the PTEN mutation develop T-cell lymphomas associated with the loss of heterozygosity at the PTEN locus (Stambolic et al. 1998). Although PTEN is a negative regulator of basal PKB activity, it does not regulate PKB activation following growth factor stimulation (Myers et al. 1998). Our results implicate the 5′ inositol phosphatase SHIP as the critical negative regulator of growth factor-mediated activation of the cell survival PKB. Activation-dependent and receptor-specific recruitment of SHIP to the site of signaling may ensure the down-regulation of PI(3,4,5)P3-mediated signals, particularly the activation of PKB. Perturbations of the PI3′K/phosphoinositide signaling pathways would then lead to severe consequences, such as the chronic progressive myeloid hyperplasia in SHIP−/− mice and tumorigenesis in PTEN−/− mice. Several other growth factor receptor-regulated 5′ phosphoinositol phosphatases have been described recently (Guilherme et al. 1996; Pesesse et al. 1997). Like PTEN and SHIP, these enzymes may have a role in regulating cellular homeostasis and cell survival, and may represent attractive targets in the search for novel tumor suppressor genes in human populations.

Materials and methods

Generation of SHIP-deficient mice

Embryonic stem (ES) cells heterozygous for a gene-targeted mutation of SHIP (SHIP+/−) were generated as described (Liu et al. 1998a). Two independent SHIP+/− ES lines were injected into blastocysts of C57BL/6 mice. Tail DNA from agouti mice was digested with EcoRV, Southern blotted, and hybridized to a 1.8-kb BamHI fragment of the SHIP genomic clone to follow the transmission of the mutated allele. Homozygous mice were generated by crossing heterozygotes. Genotypes were identified by Southern blotting of genomic DNA. Deletion of SHIP protein was confirmed by Western blotting using an antibody raised against amino acid residues 276–540 of the SHIP molecule (Liu et al. 1998b). Mouse strains derived from both ES cell lines were similar in phenotype. Mice were maintained at the animal facilities of the Ontario Cancer Institute in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Histology

Organs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution, dehydrated in ethanol, and embedded in paraffin for sectioning. Sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using standard protocols.

Isolation of neutrophils and mast cells

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 ml of 9% casein, followed by a second injection 16 hrs later. Neutrophils were isolated by peritoneal lavage 3 hr after the second injection. Lavage was performed by washing the peritoneal cavity twice with 5 ml of PBS. Cells were washed and resuspended in OptiMEM medium in the presence or absence of 10ng/ml mouse GM-CSF (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA) 30 min prior to exposure to apoptotic stimuli. Bone marrow cells were flushed from femurs of SHIP−/− and control littermate mice. Cells were washed twice with PBS and resuspended at 5 × 105/ml in OptiMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 μm β-mercaptoethanol, antibiotics (penicillin plus streptomycin, GIBCO/BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), and 2 ng/ml recombinant mouse IL3 (Genzyme). After 6 weeks incubation, nearly 100% of the cells were c-Kit+FcεR1+Mac1− mast cells (termed BMMCs) as determined by flow cytometry. FITC-conjugated anti-FcεR1, PE-conjugated anti-Mac1, and biotin-conjugated anti-c-Kit mAbs used in flow cytometry analyses were purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Cells were analyzed using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Analysis of cell death

Cells were washed with PBS to remove growth factors (IL3 or GM–CSF) and 3 × 105 cells were plated and treated as indicated. Twenty-four hours after treatment, cells were washed with PBS and the percentage of cell death determined by positive 7-amino-actinomycin D (7AAD) staining (Schmid et al. 1994). Apoptosis was also determined using the Annexin V apoptosis detection kit (PharMingen). For analysis of chromatin condensation, cells were prepared by cytospinning and fixed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were then stained with DAPI (4′,6-diaminino-phenylindole, Sigma, St Louis, MO) in water (1 μg/ml) for 5 min, rinsed with water, mounted, and visualized under a fluorescence microscope.

Western blot and immunoprecipitation

BMMCs (1 × 106 cells/100 μl of PBS) were stimulated with PBS alone or with IL3 (5 ng/ml) at 37°C for various time periods. To terminate stimulation, cells were immediately diluted with 1 ml of ice-cold PBS containing 1 mmsodium vanadate (Na3VO4), pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in 20 μl of ice-cold lysis (PLC) consisting of 1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, 50 mm HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, 100 mm NaF, 1 mmPMSF, and 1 mm Na3VO4. Whole cell lysates were analyzed on SDS–polyacrylamide gels (Novex, San Diego, CA). Proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P transfer membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and immunoblotted with phosphospecific PKB/Akt antibodies (Ser-473; Thr-308; New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) to reveal the presence of activated PKB/Akt. To verify equivalent loading and to confirm the identity of the phosphorylated PKB/Akt, membranes were stripped with 100 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 62.5 mm Tris (pH 6.7) at 55°C for 30 min and blotted with an anti-PKB antibody (New England Biolabs). Immunoblots were visualized with ECL detection reagents (Amersham, Buckinghamshire,UK). For immunoprecipitations, 107 cells were lysed in 1 ml of PLC buffer and soluble cell lysates were incubated with the indicated antibodies and protein G–Sepharose (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) at 4°C for 1 hr following the standard protocol.

Metabolic cell labeling and lipid extraction

Cells (107) were labeled with 0.25 mCi/ml [32P]orthophosphate (NEN/Dupont ) in phosphate-free RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 0.1% BSA (fatty acid-free) and 10 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) for 1 hr at 37°C. Cells were washed twice with medium and stimulated with 5 ng/ml IL3 for the indicated periods of time or with 10 μg/ml anti-dinitrophenyl IgE mAbSPE7 (Sigma) for 5 min. Treatments were quenched by the addition of chloroform/methanol/8% HClO4 (5:10:4). After vigorous vortexing, chloroform/HClO4 (1:1) was added to isolate the organic phase, which was washed four times in chloroform-saturated 1% HClO4 before drying. Dried lipids were resolved in chloroform/methanol (95:5) by thin layer chromatography as described (Sasaki et al. 1996).

Acknowledgments

We thank Vuk Stambolic for helpful discussions, Gordon Duncan, and Carol Murden for assistance, and Mary Saunders for scientific editing.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL Jpenning@amgen.com; FAX (416) 204-2278.

References

- Alessi DR, James SR, Downes CP, Holmes AB, Gaffney PRJ, Reese CB, Cohen P. Characterization of a 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase which phosphorylates and activates protein kinase Bα. Curr Biol. 1997;7:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley MT, Harmer SL, DeFranco AL. Activation-induced association of a 145-kDa tyrosine-phosphorylated protein with Shc and Syk in B lymphocytes and macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1145–1152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damen JE, Liu L, Cutler RL, Krystal G. Erythropoietin stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc and its association with Grb2 and a 145-kd tyrosine phosphorylated protein. Blood. 1993;82:2296–2303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damen JE, Liu L, Rosten P, Humphries RK, Jefferson AB, Majerus PW, Krystal G. The 145-kDa protein induced to associate with Shc by multiple cytokines is an inositol tetraphosphate and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate 5-phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:1689–1693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deGroot RP, Coffer PJ, Koenderman L. Regulation of proliferation, differentiation and survival by the IL-3/IL-5/GM-CSF receptor family. Cell Signal. 1998;10:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(98)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcommenne M, Tan C, Gray V, Rue L, Woodgett J, Dedhar S. Phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase-dependent regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 and protein kinase B/Akt by the integrin-linked kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:11211–11216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downward J. Mechanisms and consequences of activation of protein kinase B/Akt. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:262–267. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke TF, Kaplan DR, Cantley LC. PI3′K: Downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell. 1997;88:435–437. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilherme A, Klarlund JK, Krystal J, Czech MP. Regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate 5′-phosphatase activity by insulin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29533–29536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgason CD, Damen JE, Rosten P, Grewal R, Sorensen P, Chappel M, Borowski SM, Jirik F, Krystal, G. G, Humphries R K. Targeted disruption of SHIP leads to hemopoietic perturbations, lung pathology, and a shortened life span. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1610–1620. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings BA. Signal transduction–Akt signaling: Linking membrane events to life and death decision. Science. 1997;275:628–630. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5300.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber M, Helgason CD, Damen JE, Liu L, Humphries RK, Krystal G. The src homology 2-containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP) is the gatekeeper of mast cell degranulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:11330–11335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Sakamoto H, Appella E, Siraganian RP. The negative signaling molecule SH2 domain-containing inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase (SHIP) binds to the tyrosine-phosphorylated β subunit of the high affinity IgE receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13991–13996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klippel A, Kavanaugh WM, Pot D, Williams LT. A specific product of phosphotidylinositol 3-kinase directly activates the protein kinase Akt through its pleckstrin homology domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:338–344. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioubin MN, Myles GM, Carlberg K, Bowtell D, Rohrschneider LR. SHC, GRB2, SOS1, and a 150-kDa tyrosine-phosphorylated protein form complexes with Fms in hematopoietic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5682–5691. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioubin MN, Algate PA, Tsai S, Carlberg K, Aebersold R, Rohrschneider LR. p150SHIP, a signal transduction molecule with inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase activity. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1084–1095. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Damen JE, Hughes ME, Babic I, Jirik FR, Krystal G. The Src homology (SH2) domain of SH2-containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP) is essential for tyrosine phosphorylation of SHIP, its association with Shc, and its induction of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8983–8988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Oliveira-Dos-Santos AJ, Mariathasan S, Bouchard D, Jones J, Sarao R, Kozieradzki I, Ohashi PS, Penninger JM, Dumont DJ. The inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase SHIP is a crucial negative regulator of BCR signaling. J Exp Med. 1998a;188:1333–1342. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.7.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Shalaby F, Jones J, Bouchard D, Dumont DJ. The SH2-containing inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase, SHIP, is expressed during haematopoiesis and spermatogenesis. Blood. 1998b;91:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehama T, Dixon JE. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC12, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima A, Mui A, Ogorochi T, Sakamaki K. Receptors for granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulation factor, interleukin 3 and interleukin 5. Blood. 1993;82:1960–1974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MP, Pass I, Batty IH, Van der Kaay J, Stolarov JV, Hemmings BA, Wigler MH, Downes CP, Tonks NK. The lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN is critical for its tumor suppressor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:3513–13518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Bolland S, Tempst P, Ravetch JV. Role of the inositol phosphatase SHIP in negative regulation of the immune system by the receptor FcγRIIB. Nature. 1996;383:263–266. doi: 10.1038/383263a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Okada H, Bolland S, Yanagi S, Kurosaki T, Ravetch JV. Deletion of SHIP or SHP-1 reveals two distinct pathways for inhibitory signaling. Cell. 1997;90:293–301. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesesse X, Deleu S, De Smedt F, Drayer L, Erneux C. Identification of a second SH2-domain-containing protein closely related to the phosphatidylinositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase SHIP. Biochem Biophys Res Commu. 1997;239:697–700. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff M. Cell suicide for beginners. Nature. 1998;396:119–122. doi: 10.1038/24055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozakis-Adcock M, McGlade J, Mbamalu G, Pelicci G, Daly R, Li W, Batzer A, Thomas S, Brugge J, Pelicci PG. Association of the Shc and Grb2/Sem5-containing proteins is implicated in activation of the Ras pathway by tyrosine kinases. Nature. 1992;17:689–692. doi: 10.1038/360689a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Hazeki K, Hazeki O, Ui M, Katada T. Focal adhesion kinase (p125FAK) and paxillin are substrates for sphigomyelinase-induced tyrosine phosphorylation in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts. Biochem J. 1996;315:1035–1040. doi: 10.1042/bj3151035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid I, Uittenbogaart CH, Giorgi JV. Sensitive method for measuring apoptosis and cell surface phenotype in human thymocytes by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1994;15:12–20. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990150104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, Brothers GM, Mirtsos C, Sasaki T, Ruland J, Penninger JM, Siderovski DP, Mak TW. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor pTEN. Cell. 1998;95:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]