Abstract

Prolactin (PRL) is critical for alveolar proliferation and differentiation in normal mammary development and is also implicated in breast cancer. PRL influences cell proliferation and growth by altering the expression of cyclin D1. Cyclin D1 expression is directly regulated by PRL through the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)/signal transducer and activator of transcription 5-mediated transcriptional activation of the cyclin D1 promoter. A p21-activated serine-threonine kinase (PAK)1 has also been implicated in the regulation of cyclin D1 gene expression. We have previously demonstrated that JAK2 directly phosphorylates PAK1 and extend these data here to demonstrate that PAK1 activates the cyclin D1 promoter in response to PRL. We show that mutation of PAK1 Tyr 153, 201, and 285 (sites of JAK2 phosphorylation; PAK1 Y3F) decreases both PAK1 nuclear translocation in response to PRL and PRL-induced cyclin D1 promoter activity by 55%. Mutation of the PAK1 nuclear localization signals decreases PRL-induced cyclin D1 promoter activity by 46%. A PAK1 Y3F mutant lacking functional nuclear localization signals decreases PRL-induced cyclin D1 activity by 68%, suggesting that there is another PAK1-dependent mechanism to activate the cyclin D1 promoter. We have found that adapter protein Nck sequesters PAK1 in the cytoplasm and that coexpression of both PAK1 and Nck inhibits the amplifying effect of PRL-induced PAK1 on cyclin D1 promoter activity (95% inhibition). This inhibition is partially abolished by disruption of PAK1-Nck binding. We propose two PAK1-dependent mechanisms to activate cyclin D1 promoter activity in response to PRL: via nuclear translocation of tyrosyl-phosphorylated PAK1 and via formation of a Nck-PAK1 complex that sequesters PAK1 in the cytoplasm.

Prolactin (PRL), a hormone used at both the endocrine and autocrine levels, regulates the differentiation of secretory glands, including the mammary gland, ovary, prostate, submaxillary and lacrimal glands, pancreas, and liver (for review, please see Ref. 1). PRL also regulates the proliferation of different cell types, including mammary epithelium, pancreatic β-cells, astrocytes, anterior pituitary cells, adipocytes, and T lymphocytes (2–7). Increasing evidence supports the involvement of PRL in breast cancer. The PRL receptor (PRLR) is detected in 80% of human breast cancers (8) and is overexpressed in tumor cells (9). PRL has a mitogenic action in breast cells (10). Exogenous administration of PRL increased the proliferation of breast cancer cells (11–13). Similarly, proliferation of breast cancer cells that were induced to produce endogenous PRL was increased 1.5 times compared with noninduced cells; this effect was magnified by the addition of estradiol (14). Additionally, there is a high breast cancer rate in transgenic mice overexpressing lactogenic hormones (15). The addition of PRL antibodies inhibited cell proliferation and halted cell cycle progression in breast cancer cells (16–18) and in mouse studies (19).

Initiation of PRL signaling involves PRL binding to PRLR and activation of the tyrosin (Tyr) kinase Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), which, in turn, phosphorylates the PRLR. Phosphorylated Tyr within the receptor and JAK2 recruit an array of effector and/or signaling proteins. The best identified target of JAK2 is a family of transcription factors termed signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT). STAT exist within the cytoplasm in a latent or inactive state; they are recruited by cytokine receptor complexes through an interaction involving a phosphotyrosine (on the cytokine receptor and/or the associated JAK) and the Sarc homology (SH)2 domain of the STAT protein (20–22). Three members of the STAT family participate in PRL signaling: STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 (both A and B isoforms) (23–25). STAT5 was originally identified as mammary gland factor (26) and is the major STAT activated by PRL. JAK2 phopshorylation of STAT leads to their dimerization and translocation into the nucleus, where they bind to specific response elements [γ-interferon activation sequence (GAS) sequence] in the promoter of target genes. The human cyclin D1 promoter contains two consensus GAS sites at −457 and −224. PRL induces STAT5 binding to the more distal GAS site (GAS1) to enhance cyclin D1 promoter activity (27). PRL also induces cyclin D1 promoter activity by removing a ubiquitous transcriptional factor Oct-1 from the GAS2 site in the cyclin D1 promoter (28).

Cyclins regulate progression through the cell cycle, and dysregulated expression of cyclins and/or cyclin-dependent kinases can lead to aberrant cellular growth, proliferation, and tumorigenesis. Among regulators of the cell cycle, cyclin D1 is a strong candidate target of PRL signaling, because females deficient in cyclin D1 exhibit impaired mammary gland development similar to STAT5 knockout mice (29, 30). PRL is thought to influence cell proliferation and growth by altering the expression of cyclins D1 and B1 (11, 27, 28). The cyclin D1 gene is amplified or overexpressed in up to 50% of human breast cancers (31, 32), and overexpression of cyclin D1 in transgenic mice leads to mammary tumor formation (33). PRL-induced increase of cyclin D1 expression is associated with hyperphosphorylation of the Rb protein at Ser 780, indicating increased cyclin-dependent kinase 4 activity (11). Using mammary cells from JAK2 knockout mice, JAK2 has been shown to control expression of the cyclin D1 mRNA and regulate the accumulation of cyclin D1 protein in the nucleus by inhibiting signal transducers that mediate the phosphorylation and nuclear export of cyclin D1 (34). In addition to cyclins D1 and B1, a significant increase in cyclins A and E expression has been also detected in many breast cancers (35, 36).

We have recently linked PRL signaling to the p21-activated serine-threonine kinase (PAK)1 and shown that JAK2 directly phosphorylates PAK1 (37). PAK1 is a member of a conserved family of PAK and is important for a variety of cellular functions, including cell morphogenesis, motility, survival, mitosis, and malignant transformation (for review, please see Refs. 38–40). The emerging roles of PAK1 in the regulation of multiple fundamental cellular processes have directed significant attention toward understanding how PAK1 activity is controlled. Autoinhibition of the PAK1 C-terminal catalytic domain by the N-terminal domain is a key mechanism of PAK1 regulation. Several layers of inhibition, involving dimerization and occupation of the catalytic cleft by contact between the N- and C-terminal domains, keep PAK1 kinase activity in check (41). Autoinhibition of PAK1 occurs in trans, meaning that the inhibitory domain of one PAK1 molecule interacts with the kinase domain of another PAK1 molecule (42). Association of GTP-bound forms of cell division cycle 42 (Cdc42) and Rac1 with the PAK1 p21-binding domain/Cdc42/Rac interactive binding domain induces conformational changes in the N-terminal domain that no longer support its autoinhibitory function. In addition to Cdc42 and Rac1, PAK1 is activated by the binding of small GTPases, Rac2 and Rac3, as well as TC10, CHP, and Wrich-1 proteins (43–48). PAK1 is a predominantly cytoplasmic protein but is activated upon recruitment to the cell membrane. PAK1 membrane localization occurs through interaction with adaptor proteins Nck, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2, and PAK-interactive exchange factor, all of which are activated by ligation of growth-factor receptors (49–52). Membrane recruitment of PAK1 via adapter proteins and subsequent PAK1 activation may involve phosphorylation at Thr 423 (a site that is also autophosphorylated when PAK1 is activated by Rac1 and Cdc42) by PDK1 (53) or interaction with lipids, such as sphingosine, that can activate PAK1 in a GTPase-independent manner (54). In addition to PDK, several other protein kinases regulate PAK1. Thus, Akt1 phosphorylates PAK1 at Ser 21, decreasing Nck binding to the PAK1 N terminus and stimulating PAK1 activity (55, 56). The p35-bound form of cyclin-dependent kinase 5, a neuron-specific protein kinase, associates with and phosphorylates PAK1 at Thr 212 and inhibits PAK1 kinase activity (57, 58). The cyclin B-bound form of Cdc2 also phosphorylates PAK1 at Thr 212 (59, 60), affecting PAK1 protein-protein interaction but not PAK1 activation (59).

Accumulating evidence suggests that some PAK1 functions can be kinase independent. Thus, PAK1 can regulate the actin cytoskeleton in both kinase-dependent and kinase-independent ways (61, 62). It has been shown that the kinase inhibitory domain (KID) of PAK1 induces cell cycle arrest independently of PAK1 kinase activity (63). We have previously proposed that tyrosyl phosphorylation of PAK1 by JAK2 creates high-affinity docking sites for binding to SH2-domain-containing proteins and alters the ability of PAK1 to find, bind, and/or phosphorylate intracellular targets, thereby amplifying the effect of PAK1 on cell functions (37).

PAK1 is involved in breast cancer progression (for review, please see Refs. 64, 65). PAK1 is overexpressed (66) or up-regulated (67–69) in some breast cancers. Overexpression of PAK1 was observed in 34 of 60 breast tumor specimens (69), and expression of PAK1 in human breast tumors correlates with tumor grade, with higher expression observed in less differentiated ductal breast carcinomas (grade III) than in grade I and II tumors (68). Highly proliferating human breast cancer cell lines and tumor tissues express hyperactive PAK1 and its upstream regulator Rac3 (45). Activated PAK1-increased cell invasion of breast cancer cells and expression of a kinase-dead PAK1 mutant in the highly invasive breast cancer cell lines led to a reduction in invasiveness (70). Conversely, hyperactivation of the PAK1 pathway in the noninvasive breast cancer cell line MCF-7 promotes cell migration and anchorage-independent growth (67). Recently PAK1 has been shown to phosphorylate dynein light chain 1 that plays a critical role in tumorigenic phenotypes of dynein light chain 1 in breast cancer cells (71). Thus, PAK1 has become one of the focal points in the investigation into the mechanism and onset of human breast cancer.

PAK1 has also been implicated in regulation of cyclin D1 gene expression. Overexpression of catalytically active PAK1 T423E in MCF7 cells leads to cyclin D1 expression, whereas overexpression of PAK1 lacking the nuclear localization signals (NLS) does not (69, 72, 73). Reducing PAK1 expression by PAK1-small interfering RNA is accompanied by a significant reduction of cyclins D1 and B1 expression (69). PAK1 has a well-established role in the nucleus, where it associates with chromatin and phosphorylates histone H3 and several transcription factors and transcriptional coregulators (74–76; for review, please see Ref. 77).

Understanding the mechanism by which PRL stimulates mitogenesis and how it interacts with other factors important in breast cancer may lead to improved diagnostic assays and therapeutic approaches. In this study, we have linked PRL and PAK1 as the JAK2 substrate to the stimulation of cyclin D1 promoter activity. We have proposed two mechanisms by which PRL regulates cyclin D1 promoter activity. The first is a positive effect that depends on the PRL-dependent phosphorylation of three Tyr on PAK1 and the presence of PAK1 NLS. The second is a counterregulatory mechanism that involves the interaction between PAK1 and adapter protein Nck, which keeps the Nck-PAK1 complex in the cytoplasm.

Results

PRL-activated tyrosyl-phosphorylated PAK1 stimulates cyclin D1 promoter activity

Both PAK1 and PRL have previously been implicated in the regulation of cyclin D1 promoter activity (27, 69). Because we have recently shown that PRL causes tyrosyl phosphorylation of PAK1 by JAK2 kinase (37), we decided to investigate whether tyrosyl phosphorylation of PAK1 is important for cyclin D1 regulation in response to PRL. First, we measured the induction of cyclin D1 promoter activity in T47D cells treated with or without PRL. As shown in Fig. 1A, T47D cells transfected with a human cyclin D1 promoter-luciferase construct increased luciferase expression in response to PRL as expected. Second, cotransfection of T47D cells with luciferase construct and PAK1 wild type (WT) results in a 4.6-fold increase in luciferase expression in the absence of PRL that corresponds to previously published data (Fig. 1B, white bars) (69). Interestingly, treatment of the PAK1 WT-expressing cells with PRL causes a 14-fold increase in luciferase expression as compared with the cells not expressing PAK1 WT and treated with PRL (Fig. 1B, black bars). Overexpression of PAK1 lacking the three phosphorylated Tyr (PAK1 Y3F), which are sites of JAK2 phosphorylation, reduced PAK1's effect on cyclin D1 promoter activity by 55%, compared with PAK1 WT in the presence of PRL. These data suggest that Tyr 153, 201, and 285 of PAK1 are required for maximal cyclin D1 promoter activity in response to PRL.

Fig. 1.

PRL stimulates cyclin D1 promoter activity through Tyr 153, 201, and 285 of PAK1. T47D cells were transfected with cyclin D1-luciferase reporter (A) or cotransfected with cyclin D1-luciferase reporter with vector, PAK1 WT, or PAK1 Y3F (B). The cells were serum deprived for 24 h, treated with (black bars) or without (white bars) 500 ng/ml of PRL for an additional 24 h, lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Luciferase activity was normalized with β-galactosidase activity. Bars represent mean ± se; *, P < 0.05, n = 3.

PAK1 shuttles between the cytoplasm and nucleus and PRL promotes PAK1 nuclear accumulation

Data from the literature suggest that PAK1 translocates into the nucleus in response to epidermal growth factor (EGF) (74), and we wished to investigate the potential significance of PAK1 nuclear localization for cyclin D1 regulation. We first studied whether PRL can stimulate nuclear translocation of PAK1. Figure 2A indicates that treatment of T47D cells with PRL for 24 h caused nuclear accumulation of endogenous PAK1. Interestingly, extended incubation of T47D cells with PRL up to 48 h led to redistribution of PAK1 back to the cytoplasm. These immunofluorescence data were confirmed by fractionation assay demonstrating the presence of PAK1 in both cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions before PRL treatment, elevated levels of PAK1 in the nuclear fraction 24 h after PRL addition, and a decrease in nuclear PAK1 after 48 h (Fig. 2, B and C).

Fig. 2.

PRL causes translocation of endogenous PAK1 into nucleus. A, T47D cells were deprived of serum for 24 h and treated with or without 500 ng/ml PRL for 0, 24, or 48 h. Endogenous PAK1 was subjected to confocal immunofluorescence with αPAK1 antibody. Scale bar, 50 μm. B, Analysis of subcellular fractions of T47D cells treated as in A. Total cell lysates, cytosolic, and nuclear fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with αPAK1, αpaxillin as a cytosolic marker, and αRARα as a nuclear marker. The PAK doublet detected represents PAK1 (upper band) and PAK2 (lower band). C, The graph represents densitometric analysis of the bands obtained for PAK1 in nuclear fractions. Bars represent mean ± se; *, P < 0.05 compared with cells treated with PRL for 48 h, n = 4.

To investigate the role of the three sites of JAK2-dependent tyrosyl phosphorylation of the PAK1 molecule in nuclear translocation, we overexpressed either PAK1 WT or PAK1 Y3F in T47D cells, treated them with or without PRL to activate JAK2, and defined the amount of cells with nuclear PAK1 (Fig. 3, A and B). There were significantly more cells with intranuclear PAK1 WT after PRL treatment than without PRL, whereas there was no PRL-dependent difference in localization of PAK1 Y3F mutant, suggesting that these three Tyr may play a role in PAK1 nuclear translocation. We have also seen significant PAK1 translocation into the nucleus when we overexpressed PAK1 WT with JAK2 in COS-7 and MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4, left two bars in each plot).

Fig. 3.

Tyrosyl phosphorylation of PAK1 is required for translocation of PAK1 into nucleus in response to PRL. A, T47D cells were transfected with either PAK1 WT or PAK1 Y3F. The cells were serum deprived for 24 h, treated with or without 500 ng/ml of PRL for an additional 24 h, and PAK1 was immunolocalized with αPAK1 antibody. Scale bar, 25 μm. B, The percentage of cells with PAK1 nuclear localization was counted and plotted; 100 PAK1-expressing cells were assessed for PAK1 or PAK1 Y3F immunolocalization in each experiment for each type of treatment. Bars represent mean ± se; *, P < 0.05, n = 3.

Fig. 4.

PAK1 shuttles between cytoplasm and nucleus. PAK1 alone (T47D cells) or PAK1 and JAK2 (COS-7 and MCF-7 cells) were overexpressed in the indicated cells. The cells were incubated with LMB for 8 h and processed for immunolocalization of PAK1 with αPAK1 antibody. T47D cells were treated with 500 ng/ml of PRL for 48 h before LMB was added. The percentage of cells with PAK1 nuclear localization was counted and plotted; 100 PAK1-positive (for T47D cells), and both PAK1- and JAK2-positive (for COS-7 and MCF-7 cells) cells were assessed for PAK1 immunolocalization in each experiment for each type of treatment. Scale bar, 25 μm. Bars represent mean ± se; *, P < 0.05, n = 3.

Because the maximal amount of nuclear endogenous PAK1 was observed 24 h, but not 48 h, after PRL treatment, we hypothesize that PAK1 may shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. To test this hypothesis, we treated T47D cells with Leptomycin B (LMB), a specific inhibitor of Crm1-dependent nuclear export. Indeed, LMB treatment lead to nuclear accumulation of overexpressed PAK1 WT in T47D, MCF-7, and COS-7 cells, indicating that nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of PAK1 was happening and that this occurred in a cell type-independent manner (Fig. 4).

Effect of NLS and tyrosyl phosphorylation of PAK1 on cyclin D1 promoter activity

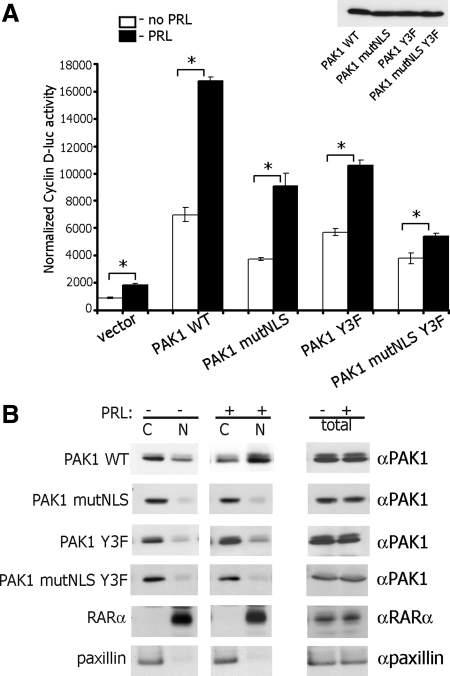

To further implicate a regulatory role of PAK1 tyrosyl phosphorylation in nuclear localization and the regulation of cyclin D1 transcription, we used a previously described PAK1 mutant, in which three NLS have been mutated by replacing the three basic lysine residues with alanines (amino acids 48–51 for NLS1, 243–245 for NLS2, and 267–269 for NLS3) (74). Because overexpression of this PAK1 mutant lacking the three functional NLS (PAK1 mutNLS) decreased but did not eliminate augmentation of cyclin D1 promoter activity compared with PAK1 WT (72), we hypothesize that mutation of Tyr 153, 201, and 285 in PAK1 mutNLS will further reduce PRL-induced activation of cyclin D1 promoter. To test this, we transiently expressed PAK1 mutNLS or PAK1 mutNLS Y3F mutants in T47D cells, treated the cells with or without PRL, and performed experiments as described above. As shown in Fig. 5A, expression of PAK1 mutNLS decreased both PRL-dependent and PRL-independent cyclin D1 transcription activity by 46%, i.e. to a similar level caused by expression of PAK1 Y3F mutant (47% inhibition in this experiment). Expression of PAK1 mutNLS Y3F significantly decreased the effect of PRL on cyclin D1 promoter activity by 68%, suggesting that both nuclear localization and tyrosyl phosphorylation of PAK1 are required for the maximal effect of PRL on cyclin D1 promoter activity. Figure 5B indicates that treatment of T47D cells with PRL caused nuclear accumulation of overexpressed PAK1 WT but not PAK1 mutNLS, PAK1 Y3F, or PAK1 mutNLS Y3F mutants.

Fig. 5.

Effect of PAK1 NLS and tyrosyl phosphorylation on cyclin D1 promoter activity. T47D cells were cotransfected with cyclin D1-luciferase reporter with either vector, PAK1 WT, PAK1 mutNLS (three NLS mutated), PAK1 Y3F, or PAK1 mutNLS Y3F. The cells were serum deprived for 24 h, treated with (black bars) or without (white bars) 500 ng/ml of PRL for an additional 24 h, lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Luciferase activity was normalized with β-galactosidase activity. Bars represent mean ± se; *, P < 0.05, n = 3. The expression levels of PAK1 WT and PAK1 mutants are indicated (A). Total cell lysates, cytosolic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions of T47D cells transfected with PAK1 WT or PAK1 mutants and treated with or without PRL were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with αPAK1, αpaxillin as a cytosolic marker, and αRARα as a nuclear marker (B).

Nck regulates PAK1 nuclear localization and inhibits PAK1-stimulated cyclin D1 promoter activity

In our search for additional PAK1-dependent mechanisms of cyclin D1 promoter activation, we investigated a role for the adapter protein Nck, because Nck is a known binding partner of PAK1 (49, 78), which is known to shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus (79). We first investigated the effect of Nck expression on PAK1 nuclear relocation in response to PRL by overexpressing PAK1 WT alone, Nck alone, or PAK1 with Nck together and treating T47D cells with or without PRL. The number of the cells with nuclear PAK1 and the number of cells with nuclear Nck were counted and plotted (Fig. 6, B and C). As illustrated in Fig. 6, A–C, Nck retained PAK1 in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6B, two left white bars) and inhibited PAK1 nuclear translocation in response to PRL (Fig. 6B, two left black bars). This effect was partially inhibited by expressing PAK1 Y3F instead of PAK1 WT but only for PRL-untreated cells (PAK1 WT + Nck vs. PAK1 Y3F + Nck without PRL) (Fig. 6B, white bars). We did not see a significant difference between the cells expressing the same constructs but treated with PRL (PAK1 WT + Nck vs. PAK1 Y3F-Nck with PRL) (Fig. 6B, black bars). These data suggest that the three Tyr on PAK1 may play a role in localization of the PAK1-Nck complex, but this effect is not affected by PRL-dependent tyrosyl phosphorylation. Interestingly, the percentage of cells in which Nck localized to both the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments was decreased by up to 45% when it was coexpressed with PAK1 (Fig. 6, A and C). This effect was independent of PRL treatment (Fig. 6, A and C). These data suggest that Nck sequesters PAK1 in the cytoplasm and that it stays in the cytoplasm itself when complexed with PAK1. Tyrosyl phosphorylation of PAK1 on the three Tyr assessed does not play a role in this process (Fig. 6, A and C, last two bars).

Fig. 6.

Nck retains PAK1 in the cytoplasm. T47D cells were either transfected with PAK1 WT or Nck or cotransfected with Nck and either PAK1 WT or PAK1 Y3F, serum deprived for 24 h, and treated with or without 500 ng/ml of PRL for an additional 24 h. PAK1 and Nck were immunolocalized with αPAK1 or αNck, correspondingly. Scale bar, 25 μm. A, The percentage of cells with PAK1 (B) or Nck (C) nuclear localization was counted and plotted; 100 PAK1-expressing or both PAK1- and Nck-expressing cells were assessed for PAK1 or Nck immunolocalization in each experiment for each type of treatment. Bars represent mean ± se; *, P < 0.05, n = 3.

Data from the experiments with the luciferase-cyclin D1 promoter construct demonstrated that coexpression of Nck with PAK1 WT strongly inhibited (by 95%) the impact of PAK1 on cyclin D1 promoter activity both in the presence and absence of PRL (Fig. 7A). This inhibition was much stronger than that caused by expression of PAK1 Y3F (by 60%).

Fig. 7.

Nck blocks the amplifying effect of PAK1 on cyclin D1 promoter activity. A, T47D cells were cotransfected with cyclin D1-luciferase reporter and either PAK1 WT, PAK1 and Nck, PAK1 Y3F, or PAK1 Y3F and Nck. The cells were serum deprived for 24 h, treated with (black bars) or without (white bars) 500 ng/ml of PRL for an additional 24 h, lysed, and luciferase activity was measured. Luciferase activity was normalized with β-galactosidase activity. Bars represent mean ± se; *, P < 0.05 compared with cells expressing PAK1 WT and untreated with PRL, n = 3. B, Whole-cell lysates of T47D cells transfected with PAK1 WT, PAK1 Y3F, and Nck were subjected to αPAK1 and αNck Western blotting. The expression levels of PAK1 WT, PAK1 Y3F, and Nck are indicated.

To study further whether the inhibitory effect of Nck on PAK1-induced cyclin D1 promoter activity was relieved by disruption of Nck-PAK1 binding, we used two mutants: Nck W143R mutant has a mutation in the second SH3 domain and fails to bind to PAK (80), and PAK1 P13A mutant, a mutant that is unable to interact with Nck (49, 78). Our coimmunoprecipitation experiments confirmed that only PAK1 WT and Nck WT bound to each other in vivo, whereas PAK1 P13A and Nck W143R did not (Fig. 8B). Data in Fig. 8A demonstrate that PAK1 P13A and PAK1 WT augment cyclin D1 promoter activity. Mutation of tryptophan 143 to arginine in Nck had no effect on cyclin D1 promoter activity as compared with Nck WT. Expression of both PAK WT and Nck WT strongly inhibited cyclin D1 promoter activity as described before. However, disruption of Nck-PAK1 binding by expression of mutated PAK1 and Nck partially but significantly relieved the repression of PRL-dependent stimulation, induced by Nck WT (Fig. 8A). These data confirm that a functional Nck-PAK1 complex is required for optimal regulation of cyclin D1 promoter activity.

Fig. 8.

PAK1-Nck binding is required for the effect of Nck on cyclin D1 promoter activity. A, T47D cells were cotransfected with cyclin D1-luciferase reporter and cDNA encoding the indicated proteins and treated as in Fig. 7A. Luciferase activity was normalized with β-galactosidase activity. Bars represent mean ± se; *, P < 0.05 compared with cells expressing PAK1 WT and untreated with PRL, n = 3. B, Nck WT is coimmunoprecipitated with PAK1 WT (lane 5) but not with PAK1 P13A (lane 6). Nck W148R is coimmunoprecipitated neither with PAK1 WT (lane 7) nor with PAK1 P13A (lane 8). HA-tagged Nck was immunoprecipitated with αHA from T47D cells overexpressing the indicated proteins and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. The light bands in lanes 1 and 3 in the αNck blot represent endogenous Nck.

Discussion

The effect of PRL on regulation of the cell cycle progression increases our understanding of the mechanism by which PRL may stimulate growth during mammary development. Furthermore, in an abnormal genetic or environmental context, this action may contribute to mammary carcinogenesis and may point toward potential targets for pharmacological intervention in this process. Here, we introduce the serine-threonine kinase PAK1 as a possible target in the PRL-dependent signaling pathway leading to cyclin D1 activation.

PAK1 has been suggested to serve as the key effector for Rac1 activation of cyclin D1 (81). Later, PAK1 was shown to activate cyclin D1 in vivo and in vitro (69). Overexpression of both WT and catalytically active PAK1 T423E in different cell lines led to increased cyclin D1 promoter activity, and the overexpression of PAK1 T423E in MCF-7 cells also elevated levels of cyclin D1 mRNA, protein, and nuclear accumulation of cyclin D1. Reducing PAK1 expression by PAK1-small interfering RNA or overexpression of dominant negative PAK1 were accompanied by a significant reduction of cyclin D1 expression (69). The same authors demonstrated that hyperplastic mammary glands from PAK1 T423E transgenic mice exhibited increased expression of cyclin D1 as compared with the WT mice. The authors proposed a model where PAK1 regulation of cyclin D1 expression involves an nuclear factor κB-dependent pathway (69). Merlin, the NF2 tumor suppressor gene product, has been proposed as a negative regulator of PAK1-stimulated cyclin D1 promoter activity by inhibition of PAK1 activity (82). Nheu et al. (83) demonstrated that PAK activity is essential for rennin-angiotensin system-induced up-regulation of cyclin D1. All of the aforementioned studies explained the effect of PAK1 on cyclin D1 activity by the serine-threonine kinase activity of PAK1.

However, many of the effects of PAK1 seem to be independent of its kinase activity but dependent on protein-protein interaction. Thus, the KID of PAK1 induced a cell cycle arrest and inhibition of cyclin D1 and D2 expression. More importantly, this arrest could not be rescued by the expression of activated PAK1 T423E, demonstrating that KID-induced cell cycle arrest occurs independently of PAK1 kinase activity (63).

Here, we linked upstream PRL-triggered signaling via JAK2 Tyr kinase to downstream PAK1, which is a JAK2 target. We have previously demonstrated that PAK1 is a novel binding partner and a substrate of JAK2 in response to PRL activation and identified three Tyr (Tyr 153, 201, and 285) of PAK1 that are phosphorylated by JAK2 (37). Here, we have shown that PAK1, in response to PRL, causes an increase of cyclin D1 promoter activity, and mutation of three Tyr (Tyr 153, 201, and 285) inhibits this amplifying effect by 55%. In an attempt to find a mechanism of this phosphorylated on tyrosines (pTyr)-PAK1 action, we noticed that PRL causes translocation of PAK1 into the nuclei. Nuclear translocation of PAK1 in response to EGF has been previously described (74; for review, please see Ref. 77). Thus, endogenous PAK1 localizes in the nucleus in 18–24% of the interphase MCF-7 cells and directly phosphorylates histone H3 (75). PAK1 associates with the promoter of PFK-M gene and stimulates PFK-M expression and also with a portion of the NFAT1 gene and represses expression of this gene (74). In addition, increased levels of nuclear PAK1 were linked to intrinsic tamoxifen resistance of breast cancer cells (72, 75). We extended these findings and demonstrated that PAK1 shuttles between the cytoplasm and the nucleus in different cell lines, including T47D, COS-7, and MCF-7. Furthermore, we have shown that PRL-dependent PAK1 nuclear translocation depends on Tyr 153, 201, and 285, because the PAK1 Y3F mutant does not translocate into the nucleus in response to PRL. Three NLS have been mapped on PAK1, and PAK1 lacking these three functional NLS (PAK1 mutNLS) fails to translocate into the nucleus in response to EGF (74). We have shown here that PAK1 mutNLS exhibited 46% less impact on cyclin D promoter activity as compared with PAK1 WT. We hypothesized that by eliminating both PAK1 Tyr phosphorylation and functional NLS, we would completely inhibit PRL-dependent amplification of cyclin D1 promoter activity. However, PAK1 mutNLS Y3F exhibited only 68% inhibition, suggesting that both the three NLS and three Tyr, which are phosporylated by JAK2 in response to PRL, contribute to, but are not exclusively required for, the PRL-dependent induction of cyclin D1 promoter activity. Why do PAK1 mutNLS and PAK1 mutNLS Y3F, which both retain in the cytoplasm, still have an amplifying effect on cyclin D1 activity? PAK1 may activate cyclin D1 promoter activity in response to PRL via multiple mechanisms. For example, PAK1 phosphorylates specific cytoplasmic proteins that can directly or indirectly regulate cyclin D1 promoter activity. In this context, it is interesting to note that, although PRL signals via STAT5 to the distal GAS1 binding sites in the cyclin D1 promoter, coexpression of dominant negative STAT5A and PAK1 WT showed no effect on cyclin D1 promoter activity (27, 28, 69). We are currently investigating which regulatory elements of cyclin D1 promoter are affected by PRL-dependent PAK1 tyrosyl phosphorylation.

In attempt to find another mechanism that can regulate the action of PRL on the cyclin D1, we focused on Nck for several reasons. First, adapter protein Nck is a binding partner of PAK1 (49, 78). Nck W143R mutant with a mutation in the second SH3 domain fails to bind to PAK (80), and the PAK1 P13A mutant is unable to interact with Nck (49, 78). Second, Nck is present in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (84). Nck rapidly accumulates in the nucleus after the introduction of DNA damage (79). In agreement with Lawe et al. (84), who showed that nuclear localization of Nck does not depend on growth factor stimulation, we have shown here that PRL also does not cause Nck nuclear translocation and that around 65% of cells contain nuclear Nck regardless of PRL treatment. However, when we coexpressed both Nck and PAK1, both molecules were mostly retained in the cytoplasm. This effect was especially dramatic for PAK1, because 3-fold fewer cells had nuclear PAK1 as compared with cells without Nck coexpression. More importantly, Nck abolished the ability of PRL to induce PAK1 nuclear translocation. These data suggest that Nck can sequester PAK1 in the cytoplasm. This sequestering has a physiological role, because coexpression of both PAK1 and Nck inhibits the amplifying effect of PRL-induced PAK1 on cyclin D1 promoter activity (95% inhibition). This inhibition was partially abolished by disruption of the PAK1-Nck binding by using either PAK1 P13A mutant, Nck W143R mutant, or both. This partial inhibition implies the presence of Nck-PAK1-interaction-independent mechanisms that affect cyclin D1 promoter activity. Nck is a common target for a variety of growth factor receptors and becomes phosphorylated on Ser, Thr, and Tyr residues after growth factor stimulation (85–87). Nck is implicated in the regulation of different signal transduction pathways, including c-Jun N-terminal kinase and mixed lineage kinase 2 pathways (88–93). Furthermore, nuclear Nck is essential for activation of p53 in response to UV-induced DNA damage (79). Transcriptional regulation of the cyclin D1 gene as a complex and many different transcription factors have been identified that regulate the cyclin D1 promoter (reviewed in Ref. 94). The regulation of cyclin D1 by integrin signaling is well documented (reviewed in Ref. 95), and Nck is an important member of focal adhesions and integrin-dependent pathway (reviewed in Ref. 96).

It is possible that there are mechanisms other than retention of Nck-pTyr-PAK1 complex in the cytoplasm to regulate the cyclin D1 promoter activity. Nck is a binding partner of PTP-PEST (a cytosolic) (56). PTP-PEST has been shown to dephosphorylate PRL-activated JAK2 in vitro (97). We can speculate that Nck brings PTP-PEST to the PRL-induced JAK2-PAK1 complex that may lead to dephosphorylation and inactivation of JAK2. Inactive JAK2 cannot tyrosyl phosphorylate PAK1, which leads to inability of PAK1 to enhance cyclin D1 activation. Another possible common target that binds to both Nck and JAK2 is the ubiquitin ligase c-Cbl, which is a negative regulator of various signaling pathways. C-Cbl becomes tyrosyl phosphorylated after stimulation of a wide variety of receptors, including the PRLR (98). The negative regulation of PRL signaling by c-Cbl is confirmed by observations that c-Cbl repression leads to enhanced JAK2/STAT activation, whereas c-Cbl overexpression results in increased ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation of STAT5 (99, 100). Because c-Cbl binds to Nck (101, 102), we can speculate that Nck may bring c-Cbl to the PRL-induced JAK2-PAK1 complex, thus leading to proteosomal degradation of JAK2 followed by attenuation of pTyr-PAK1's effect on cyclin D1 promoter activity. Nck also binds to suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-3 and recruits Nck to the plasma membrane (103). SOCS-3 negatively regulates PRL signaling by interacting with phosphorylated PRLR, leading to JAK2 suppression and, probably, by directly interacting with JAK2, which has been shown for the erythropoietin receptor (104–106). It would be attractive to speculate that Nck-SOCS-3 complex is recruited to the plasma membrane to bind to the PRLR leading to inactivation of JAK2 and decreased pTyr-PAK1's activity toward cyclin D1 promoter. We should, however, note that we have not seen relocation of Nck to the plasma membrane in response to PRL. It is possible that the redistribution of Nck to the plasma membrane occurs shortly after ligand treatment (for example, in 30 min, as it was described for platelet-derived growth factor treatment) (103), whereas long-term treatment of PRL (24 h in the current research) has no effect on the predominantly intranuclear localization of Nck (Fig. 6).

To summarize, Fig. 9 shows an overall view of mechanisms of cyclin D1 promoter activity regulation by tyrosyl-phosphorylated PAK1 in response to PRL. First, PRL binds to the PRLR and activates JAK2, which tyrosyl phosphorylates PAK1 on three Tyr. Tyrosyl-phosphorylated PAK1 translocates into the nucleus, where it stimulates cyclin D1 promoter activity. Both tyrosyl phosphorylation of PAK1 and the three intact NLS are required for this maximal effect of PRL on cyclin D1, because PAK1 mutNLS Y3F mutant has 68% reduced ability to activate the cyclin D1 promoter. However, the more critical mechanism for PAK1-dependent regulation of cyclin D1 activation is the formation of the PAK1-Nck complex in the cytoplasm. This complex retains PAK1 in the cytoplasm, which leads to the inhibition of the amplifying effect of PAK1 on cyclin D1 promoter activity in response to PRL. Which protein(s) can regulate the formation of the Nck-PAK1 complex and what kind of role the phosphorylated Tyr on PAK1 play are currently under our investigation.

Fig. 9.

PAK1 regulates PRL-dependent cyclin D1 promoter activity by two distinct mechanisms. In response to cytokines, such as PRL, PAK1 is tyrosyl phosphorylated by JAK2 and translocates into the nucleus, where it stimulates cyclin D1 promoter activity. The NLS and the three Tyr of PAK1 are sufficient but not required for this PAK1 function, because deletion of these three phosphorylated Tyr (PAK1 Y3F) and mutation of the three NLS (PAK1 mutNLS) decreased PAK1 WT activity on cyclin D1 promoter activity by 55 and 46%, respectively. The double mutant of PAK1 (mutNLS Y3F) decreased PAK1 WT activity on cyclin D1 promoter activity by 68%. Another mechanism regulating the PAK1 function is Nck-PAK1 binding, because coexpression of PAK1 and Nck inhibited PAK1-dependent stimulation of cyclin D1 promoter activity by 95%. We propose that the Nck-PAK1 complex sequesters both molecules in the cytoplasm, thereby abolishing the amplifying effect of PAK1 on the PRL-induced activation of cyclin D1.

It is of note that both PRL and PAK1 are oncogenic. Considering that cyclin D1 promoter activity is positively regulated by tyrosyl-phosphorylated PAK1 in a PRL-dependent manner, we may speculate that the PRL-activated JAK2/PAK1 axis plays a role in breast cancer promotion. Whether JAK2-dependent phosphorylation of PAK1 plays a role in normal cells and in other types of cancer requires future investigation.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids, antibodies, and cells

cDNA encoding myc-tagged PAK1 and PAK1 Y3F were described previously (37). cDNA encoding a human cyclin D1 promoter-luciferase, Nck, and PAK1 mutNLS were described previously (27, 74, 79). A human cyclin D1-promoter-luciferase construct, D1Δ-944, contains 944 bp of proximal cyclin D1 promoter sequence upstream of a luciferase reporter (107). This complex promoter contains putative AP-1, E2F, E-box, GAS1, Oct, GAS2, Egr-1, SP-1, and CRE regulatory elements (27). The double mutant PAK1 mutNLS Y3F was created by using PAK1 mutNLS as a template, and individual Tyr were mutated to phenylalanines using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Nck W143R and PAK1 P13A mutants were created also by using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Mutations were confirmed by sequencing at the University of Michigan DNA Sequencing Core (Ann Arbor, MI). Human PRL was purchased from the National Hormone and Peptide Program (Parlow, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD). Polyclonal αPAK1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), monoclonal αNck (BD Transduction Laboratories, San Diego, CA), monoclonal αJAK2 (no. AHO1352, clone 691R5; Biosource, Camarillo, CA), mouse αhemagglutinin (HA) (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and goat αHA (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX), monoclonal αpaxillin (BD Transduction Laboratories), and polyclonal retinoic acid receptor α isoform (RARα) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) were used for immunocytochemistry and immunoblotting. Ascites containing αmouse Myc monoclonal antibody, produced by the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center Hybridoma Core (Ann Arbor, MI), was used for immunoblotting. T47D cells were provided by Ethier (Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI); MCF-7 and COS-7 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

Luciferase assay

T47D cells were cotransfected with cyclin D1-luciferase reporter with indicated plasmids and pCH110 plasmid containing a functional lacZ gene. The cells were serum deprived for 24 h, treated with or without 500 ng/ml of PRL for an additional 24 h, lysed, and luciferase activity was measured according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega, Madison, WI). Luciferase values were corrected for transfection efficiency by determining the ratio of luciferase activity to β-galactosidase activity and expressed as “normalized cyclin D1-luciferase activity.” Each transfection was performed in triplicate wells. Each experiment was performed at least three times with similar results.

Immunocytochemistry

For localization studies, T47D cells were transfected with cDNA encoding myc-tagged versions of PAK1 and HA-tagged Nck if indicated using FuGENE reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocol. T47D cells were serum deprived for 24 h and treated with or without 500 ng/ml PRL for 24 or 48 h. For LMB treatment, the cells were incubated with 5 ng/ml LMB for 8 h before fixation. The cells were processed for immunocytochemistry. The coverslips were fixed (108), blocked with 2% human serum, and incubated with αmyc followed by goat-αmouse-Alexa Fluor 594 or goat-αmouse-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) to localize myc-PAK1. For localization of both myc-PAK1 and HA-Nck, the coverslips were incubated with mouse αHA followed by goat-αmouse-Alexa Fluor 488 and rabbit αPAK1 followed by goat-αrabbit-Alexa Fluor 594. For immunolocalization of myc-PAK1, HA-Nck, and JAK2 simultaneously in COS-7 and MCF-7 cells, the cells were fixed and blocked as above and incubated with goat-αHA followed by donkey-αgoat-Alexa Fluor 350. Next, the coverslips were washed and blocked with 2% goat serum and incubated with mouse αJAK2 followed by goat-αmouse-Alexa Fluor 488 and rabbit αPAK1 followed by goat-αrabbit-Alexa Fluor 594. Staining by secondary antibody reagent alone was negligible (data not shown). Confocal imaging was performed with an Olympus 1X70 laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Coimmunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Myc-tagged versions of PAK1 and HA-tagged versions of Nck were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates using mouse αMyc or goat αHA, respectively, and protein A-agarose as described previously (109). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation

Nuclear extracts were prepared essentially as described previously (110). T47D cells were serum deprived for 24 h and treated with 500 ng/ml PRL for 0, 24, or 48 h. T47D cells were washed with PBS and scraped in 1 ml of PBS supplemented with 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin. The cells were centrifuged at 2500 rpm at 4 C for 3 min. Cell pellets were dissolved in 1 ml of hypotonic buffer [20 mm HEPES (pH7.9), 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, and 0.2% Triton X-100] supplemented with 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin. The cells were incubated on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm at 4 C for 30 sec to get the nuclear pellet. The cytoplasmic fraction was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube. The nuclear pellet was then dissolved in 150 μl of Mink lysis buffer [50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, 6 mm EGTA, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Nonidet P-40] supplemented with 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm at 4 C for 10 min. Equal amount of proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies.

Whole-cell lysates were prepared by lysing cells in 1 ml of PBS [10 mm Na2HPO4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.2% sodium azide, 0.004% sodium fluoride, 1 μg/ml approtinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mm sodium orthovanadate (pH 7.25)] and cellular debris removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g at 4 C for 10 min (84).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kumar (The George Washington University, Washington, D.C.), Dr. Schuler (University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI), and Dr. Macara (University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA) for sending cDNA encoding PAK1 mutNLS, a human cyclin D1 promoter-luciferase, and Nck, respectively; Dr. Shemshedini (University of Toledo) for providing the pCH110 plasmid containing the lacZ gene and Dr. Ethier (Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI) for providing T47D cells; the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center Hybridoma Core for the production of the ascites containing αmouse Myc monoclonal antibody; and Dr. Leaman and Dr. Shemshedini for very helpful discussion.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK88127 and R15 CA135378 (to M.D.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- Cdc42

- Cell division cycle 42

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- GAS

- γ-interferon activation sequence

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- JAK2

- Janus kinase 2

- KID

- kinase inhibitory domain

- LMB

- Leptomycin B

- NLS

- nuclear localization signal

- PAK

- p21-activated serine-threonine kinase

- PAK1 mutNLS

- PAK1 mutant lacking the three functional NLS

- PMSF

- phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride

- PRL

- prolactin

- PRLR

- PRL receptor

- pTyr

- phosphorylated on tyrosines

- RARα

- retinoic acid receptor α isoform

- SH

- Sarc homology

- SOCS

- suppressor of cytokine signaling

- STAT

- signal transducer and activator of transcription

- Tyr

- tyrosin

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Goffin V, Bernichtein S, Touraine P, Kelly PA. 2005. Development and potential clinical uses of human prolactin receptor antagonists. Endocr Rev 26:400–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yu-Lee LY. 1990. Prolactin stimulates transcription of growth-related genes in Nb2 T lymphoma cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 68:21–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yu-Lee LY, Stevens AM, Hrachovy JA, Schwarz LA. 1990. Prolactin-mediated regulation of gene transcription in lymphocytes. Ann NY Acad Sci 594:146–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. DeVito WJ, Okulicz WC, Stone S, Avakian C. 1992. Prolactin-stimulated mitogenesis of cultured astrocytes. Endocrinology 130:2549–2556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clevenger CV, Torigoe T, Reed JC. 1994. Prolactin induces rapid phosphorylation and activation of prolactin receptor-associated RAF-1 kinase in a T-cell line. J Biol Chem 269:5559–5565 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clevenger CV, Medaglia MV. 1994. The protein tyrosine kinase P59fyn is associated with prolactin (PRL) receptor and is activated by PRL stimulation of T-lymphocytes. Mol Endocrinol 8:674–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nanbu-Wakao R, Fujitani Y, Masuho Y, Muramatu M, Wakao H. 2000. Prolactin enhances CCAAT enhancer-binding protein-β (C/EBPβ) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) messenger RNA expression and stimulates adipogenic conversion of NIH-3T3 cells. Mol Endocrinol 14:307–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bonneterre J, Peyrat JP, Beuscart R, Lefebvre J, Demaille A. 1987. Prognostic significance of prolactin receptors in human breast cancer. Cancer Res 47:4724–4728 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Touraine P, Martini JF, Zafrani B, Durand JC, Labaille F, Malet C, Nicolas A, Trivin C, Postel-Vinay MC, Kuttenn F, Kelly PA. 1998. Increased expression of prolactin receptor gene assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction in human breast tumors versus normal breast tissues. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:667–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clevenger CV, Furth PA, Hankinson SE, Schuler LA. 2003. The role of prolactin in mammary carcinoma. Endocr Rev 24:1–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schroeder MD, Symowicz J, Schuler LA. 2002. PRL modulates cell cycle regulators in mammary tumor epithelial cells. Mol Endocrinol 16:45–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liby K, Neltner B, Mohamet L, Menchen L, Ben-Jonathan N. 2003. Prolactin overexpression by MDA-MB-435 human breast cancer cells accelerates tumor growth. Breast Cancer Res Treat 79:241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chakravarti P, Henry MK, Quelle FW. 2005. Prolactin and heregulin override DNA damage-induced growth arrest and promote phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase-dependent proliferation in breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol 26:509–514 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gutzman JH, Rugowski DE, Schroeder MD, Watters JJ, Schuler LA. 2004. Multiple kinase cascades mediate prolactin signals to activating protein-1 in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol 18:3064–3075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cecim M, Fadden C, Kerr J, Steger RW, Bartke A. 1995. Infertility in transgenic mice overexpressing the bovine growth hormone gene: disruption of the neuroendocrine control of prolactin secretion during pregnancy. Biol Reprod 52:1187–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ginsburg E, Vonderhaar BK. 1995. Prolactin synthesis and secretion by human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 55:2591–2595 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen WY, Ramamoorthy P, Chen N, Sticca R, Wagner TE. 1999. A human prolactin antagonist, hPRL-G129R, inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation through induction of apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res 5:3583–3593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Llovera M, Pichard C, Bernichtein S, Jeay S, Touraine P, Kelly PA, Goffin V. 2000. Human prolactin (hPRL) antagonists inhibit hPRL-activated signaling pathways involved in breast cancer cell proliferation. Oncogene 19:4695–4705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen NY, Holle L, Li W, Peirce SK, Beck MT, Chen WY. 2002. In vivo studies of the anti-tumor effects of a human prolactin antagonist, hPRL-G129R. Int J Oncol 20:813–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reich NC. 2007. STAT dynamics. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 18:511–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schindler C, Levy DE, Decker T. 2007. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J Biol Chem 282:20059–20063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lim CP, Cao X. 2006. Structure, function, and regulation of STAT proteins. Mol Biosyst 2:536–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ball RK, Friis RR, Schoenenberger CA, Doppler W, Groner B. 1988. Prolactin regulation of β-casein gene expression and of a cytosolic 120-kd protein in a cloned mouse mammary epithelial cell line. EMBO J 7:2089–2095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DaSilva L, Rui H, Erwin RA, Howard OM, Kirken RA, Malabarba MG, Hackett RH, Larner AC, Farrar WL. 1996. Prolactin recruits STAT1, STAT3 and STAT5 independent of conserved receptor tyrosines TYR402, TYR479, TYR515 and TYR580. Mol Cell Endocrinol 117:131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schaber JD, Fang H, Xu J, Grimley PM, Rui H. 1998. Prolactin activates Stat1 but does not antagonize Stat1 activation and growth inhibition by type I interferons in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 58:1914–1919 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wakao H, Gouilleux F, Groner B. 1994. Mammary gland factor (MGF) is a novel member of the cytokine regulated transcription factor gene family and confers the prolactin response. EMBO J 13:2182–2191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brockman JL, Schroeder MD, Schuler LA. 2002. PRL activates the cyclin D1 promoter via the Jak2/Stat pathway. Mol Endocrinol 16:774–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brockman JL, Schuler LA. 2005. Prolactin signals via Stat5 and Oct-1 to the proximal cyclin D1 promoter. Mol Cell Endocrinol 239:45–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fantl V, Stamp G, Andrews A, Rosewell I, Dickson C. 1995. Mice lacking cyclin D1 are small and show defects in eye and mammary gland development. Genes Dev 9:2364–2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sicinski P, Donaher JL, Parker SB, Li T, Fazeli A, Gardner H, Haslam SZ, Bronson RT, Elledge SJ, Weinberg RA. 1995. Cyclin D1 provides a link between development and oncogenesis in the retina and breast. Cell 82:621–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dickson C, Fantl V, Gillett C, Brookes S, Bartek J, Smith R, Fisher C, Barnes D, Peters G. 1995. Amplification of chromosome band 11q13 and a role for cyclin D1 in human breast cancer. Cancer Lett 90:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McIntosh GG, Anderson JJ, Milton I, Steward M, Parr AH, Thomas MD, Henry JA, Angus B, Lennard TW, Horne CH. 1995. Determination of the prognostic value of cyclin D1 overexpression in breast cancer. Oncogene 11:885–891 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang TC, Cardiff RD, Zukerberg L, Lees E, Arnold A, Schmidt EV. 1994. Mammary hyperplasia and carcinoma in MMTV-cyclin D1 transgenic mice. Nature 369:669–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sakamoto K, Creamer BA, Triplett AA, Wagner KU. 2007. The Janus kinase 2 is required for expression and nuclear accumulation of cyclin D1 in proliferating mammary epithelial cells. Mol Endocrinol 21:1877–1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Keyomarsi K, Pardee AB. 1993. Redundant cyclin overexpression and gene amplification in breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:1112–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Megha T, Lazzi S, Ferrari F, Vatti R, Howard CM, Cevenini G, Leoncini L, Luzi P, Giordano A, Tosi P. 1999. Expression of the G2-M checkpoint regulators cyclin B1 and P34CDC2 in breast cancer: a correlation with cellular kinetics. Anticancer Res 19:163–169 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rider L, Shatrova A, Feener EP, Webb L, Diakonova M. 2007. JAK2 tyrosine kinase phosphorylates PAK1 and regulates PAK1 activity and functions. J Biol Chem 282:30985–30996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bokoch GM. 2003. Biology of the p21-activated kinases. Annu Rev Biochem 72:743–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhao ZS, Manser E. 2005. PAK and other Rho-associated kinases-effectors with surprisingly diverse mechanisms of regulation. Biochem J 386:201–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kumar R, Gururaj AE, Barnes CJ. 2006. p21-activated kinases in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 6:459–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lei M, Lu W, Meng W, Parrini MC, Eck MJ, Mayer BJ, Harrison SC. 2000. Structure of PAK1 in an autoinhibited conformation reveals a multistage activation switch. Cell 102:387–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Parrini MC, Lei M, Harrison SC, Mayer BJ. 2002. Pak1 kinase homodimers are autoinhibited in trans and dissociated upon activation by Cdc42 and Rac1. Mol Cell 9:73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Manser E, Leung T, Salihuddin H, Zhao ZS, Lim L. 1994. A brain serine/threonine protein kinase activated by Cdc42 and Rac1. Nature 367:40–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Knaus UG, Bokoch GM. 1998. The p21Rac/Cdc42-activated kinases (PAKs). Int J Biochem Cell Biol 30:857–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mira JP, Benard V, Groffen J, Sanders LC, Knaus UG. 2000. Endogenous, hyperactive Rac3 controls proliferation of breast cancer cells by a p21-activated kinase-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:185–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Neudauer CL, Joberty G, Tatsis N, Macara IG. 1998. Distinct cellular effects and interactions of the Rho-family GTPase TC10. Curr Biol 8:1151–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Aronheim A, Broder YC, Cohen A, Fritsch A, Belisle B, Abo A. 1998. Chp, a homologue of the GTPase Cdc42Hs, activates the JNK pathway and is implicated in reorganizing the actin cytoskeleton. Curr Biol 8:1125–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tao W, Pennica D, Xu L, Kalejta RF, Levine AJ. 2001. Wrch-1, a novel member of the Rho gene family that is regulated by Wnt-1. Genes Dev 15:1796–1807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bokoch GM, Wang Y, Bohl BP, Sells MA, Quilliam LA, Knaus UG. 1996. Interaction of the Nck adapter protein with p21-activated kinase (PAK1). J Biol Chem 271:25746–25749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lu W, Katz S, Gupta R, Mayer BJ. 1997. Activation of Pak by membrane localization mediated by an SH3 domain from the adaptor protein Nck. Curr Biol 7:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Daniels RH, Hall PS, Bokoch GM. 1998. Membrane targeting of p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) induces neurite outgrowth from PC12 cells. EMBO J 17:754–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhao ZS, Manser E, Loo TH, Lim L. 2000. Coupling of PAK-interacting exchange factor PIX to GIT1 promotes focal complex disassembly. Mol Cell Biol 20:6354–6363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. King CC, Gardiner EM, Zenke FT, Bohl BP, Newton AC, Hemmings BA, Bokoch GM. 2000. p21-activated kinase (PAK1) is phosphorylated and activated by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1). J Biol Chem 275:41201–41209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bokoch GM, Reilly AM, Daniels RH, King CC, Olivera A, Spiegel S, Knaus UG. 1998. A GTPase-independent mechanism of p21-activated kinase activation. Regulation by sphingosine and other biologically active lipids. J Biol Chem 273:8137–8144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tang Y, Zhou H, Chen A, Pittman RN, Field J. 2000. The Akt proto-oncogene links Ras to Pak and cell survival signals. J Biol Chem 275:9106–9109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhao ZS, Manser E, Lim L. 2000. Interaction between PAK and nck: a template for Nck targets and role of PAK autophosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol 20:3906–3917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nikolic M, Chou MM, Lu W, Mayer BJ, Tsai LH. 1998. The p35/Cdk5 kinase is a neuron-specific Rac effector that inhibits Pak1 activity. Nature 395:194–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rashid T, Banerjee M, Nikolic M. 2001. Phosphorylation of Pak1 by the p35/Cdk5 kinase affects neuronal morphology. J Biol Chem 276:49043–49052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thiel DA, Reeder MK, Pfaff A, Coleman TR, Sells MA, Chernoff J. 2002. Cell cycle-regulated phosphorylation of p21-activated kinase 1. Curr Biol 12:1227–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Banerjee M, Worth D, Prowse DM, Nikolic M. 2002. Pak1 phosphorylation on t212 affects microtubules in cells undergoing mitosis. Curr Biol 12:1233–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Manser E, Huang HY, Loo TH, Chen XQ, Dong JM, Leung T, Lim L. 1997. Expression of constitutively active α-PAK reveals effects of the kinase on actin and focal complexes. Mol Cell Biol 17:1129–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vadlamudi RK, Li F, Adam L, Nguyen D, Ohta Y, Stossel TP, Kumar R. 2002. Filamin is essential in actin cytoskeletal assembly mediated by p21-activated kinase 1. Nat Cell Biol 4:681–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thullberg M, Gad A, Beeser A, Chernoff J, Strömblad S. 2007. The kinase-inhibitory domain of p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) inhibits cell cycle progression independent of PAK1 kinase activity. Oncogene 26:1820–1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kumar R, Vadlamudi RK. 2002. Emerging functions of p21-activated kinases in human cancer cells. J Cell Physiol 193:133–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gururaj AE, Rayala SK, Kumar R. 2005. p21-activated kinase signaling in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 7:5–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bekri S, Adélaïde J, Merscher S, Grosgeorge J, Caroli-Bosc F, Perucca-Lostanlen D, Kelley PM, Pébusque MJ, Theillet C, Birnbaum D, Gaudray P. 1997. Detailed map of a region commonly amplified at 11q13->q14 in human breast carcinoma. Cytogenet Cell Genet 79:125–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vadlamudi RK, Adam L, Wang RA, Mandal M, Nguyen D, Sahin A, Chernoff J, Hung MC, Kumar R. 2000. Regulatable expression of p21-activated kinase-1 promotes anchorage-independent growth and abnormal organization of mitotic spindles in human epithelial breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 275:36238–36244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Salh B, Marotta A, Wagey R, Sayed M, Pelech S. 2002. Dysregulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and downstream effectors in human breast cancer. Int J Cancer 98:148–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Balasenthil S, Sahin AA, Barnes CJ, Wang RA, Pestell RG, Vadlamudi RK, Kumar R. 2004. p21-activated kinase-1 signaling mediates cyclin D1 expression in mammary epithelial and cancer cells. J Biol Chem 279:1422–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Adam L, Vadlamudi R, Mandal M, Chernoff J, Kumar R. 2000. Regulation of microfilament reorganization and invasiveness of breast cancer cells by kinase dead p21-activated kinase-1. J Biol Chem 275:12041–12050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Vadlamudi RK, Bagheri-Yarmand R, Yang Z, Balasenthil S, Nguyen D, Sahin AA, den Hollander P, Kumar R. 2004. Dynein light chain 1, a p21-activated kinase 1-interacting substrate, promotes cancerous phenotypes. Cancer Cell 5:575–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Holm C, Rayala S, Jirström K, Stål O, Kumar R, Landberg G. 2006. Association between Pak1 expression and subcellular localization and tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:671–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rayala SK, Talukder AH, Balasenthil S, Tharakan R, Barnes CJ, Wang RA, Aldaz CM, Khan S, Kumar R. 2006. P21-activated kinase 1 regulation of estrogen receptor-α activation involves serine 305 activation linked with serine 118 phosphorylation. Cancer Res 66:1694–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Singh RR, Song C, Yang Z, Kumar R. 2005. Nuclear localization and chromatin targets of p21-activated kinase 1. J Biol Chem 280:18130–18137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Li F, Adam L, Vadlamudi RK, Zhou H, Sen S, Chernoff J, Mandal M, Kumar R. 2002. p21-activated kinase 1 interacts with and phosphorylates histone H3 in breast cancer cells. EMBO Rep 3:767–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Park JB, Kim EJ, Yang EJ, Seo SR, Chung KC. 2007. JNK- and Rac1-dependent induction of immediate early gene pip92 suppresses neuronal differentiation. J Neurochem 100:555–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Rayala SK, Kumar R. 2007. Sliding p21-activated kinase 1 to nucleus impacts tamoxifen sensitivity. Biomed Pharmacother 61:408–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Galisteo ML, Chernoff J, Su YC, Skolnik EY, Schlessinger J. 1996. The adaptor protein Nck links receptor tyrosine kinases with the serine-threonine kinase Pak1. J Biol Chem 271:20997–21000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kremer BE, Adang LA, Macara IG. 2007. Septins regulate actin organization and cell-cycle arrest through nuclear accumulation of NCK mediated by SOCS7. Cell 130:837–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zhu J, Attias O, Aoudjit L, Jiang R, Kawachi H, Takano T. 2010. p21-activated kinases regulate actin remodeling in glomerular podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298:F951–F961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Westwick JK, Lambert QT, Clark GJ, Symons M, Van Aelst L, Pestell RG, Der CJ. 1997. Rac regulation of transformation, gene expression, and actin organization by multiple, PAK-independent pathways. Mol Cell Biol 17:1324–1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Xiao GH, Gallagher R, Shetler J, Skele K, Altomare DA, Pestell RG, Jhanwar S, Testa JR. 2005. The NF2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, inhibits cell proliferation and cell cycle progression by repressing cyclin D1 expression. Mol Cell Biol 25:2384–2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nheu T, He H, Hirokawa Y, Walker F, Wood J, Maruta H. 2004. PAK is essential for RAS-induced upregulation of cyclin D1 during the G1 to S transition. Cell Cycle 3:71–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lawe DC, Hahn C, Wong AJ. 1997. The Nck SH2/SH3 adaptor protein is present in the nucleus and associates with the nuclear protein SAM68. Oncogene 14:223–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Chou MM, Fajardo JE, Hanafusa H. 1992. The SH2- and SH3-containing Nck protein transforms mammalian fibroblasts in the absence of elevated phosphotyrosine levels. Mol Cell Biol 12:5834–5842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Li W, Hu P, Skolnik EY, Ullrich A, Schlessinger J. 1992. The SH2 and SH3 domain-containing Nck protein is oncogenic and a common target for phosphorylation by different surface receptors. Mol Cell Biol 12:5824–5833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Park D, Rhee SG. 1992. Phosphorylation of Nck in response to a variety of receptors, phorbol myristate acetate, and cyclic AMP. Mol Cell Biol 12:5816–5823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Poitras L, Jean S, Islam N, Moss T. 2003. PAK interacts with NCK and MLK2 to regulate the activation of jun N-terminal kinase. FEBS Lett 543:129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Murakami H, Yamamura Y, Shimono Y, Kawai K, Kurokawa K, Takahashi M. 2002. Role of Dok1 in cell signaling mediated by RET tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem 277:32781–32790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Miyamoto Y, Yamauchi J, Mizuno N, Itoh H. 2004. The adaptor protein Nck1 mediates endothelin A receptor-regulated cell migration through the Cdc42-dependent c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 279:34336–34342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Becker E, Huynh-Do U, Holland S, Pawson T, Daniel TO, Skolnik EY. 2000. Nck-interacting Ste20 kinase couples Eph receptors to c-Jun N-terminal kinase and integrin activation. Mol Cell Biol 20:1537–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Stein E, Huynh-Do U, Lane AA, Cerretti DP, Daniel TO. 1998. Nck recruitment to Eph receptor, EphB1/ELK, couples ligand activation to c-Jun kinase. J Biol Chem 273:1303–1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Su YC, Han J, Xu S, Cobb M, Skolnik EY. 1997. NIK is a new Ste20-related kinase that binds NCK and MEKK1 and activates the SAPK/JNK cascade via a conserved regulatory domain. EMBO J 16:1279–1290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Wang C, Li Z, Fu M, Bouras T, Pestell RG. 2004. Signal transduction mediated by cyclin D1: from mitogens to cell proliferation: a molecular target with therapeutic potential. Cancer Treat Res 119:217–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Musgrove EA. 2006. Cyclins: roles in mitogenic signaling and oncogenic transformation. Growth Factors 24:13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Buday L, Wunderlich L, Tamás P. 2002. The Nck family of adapter proteins: regulators of actin cytoskeleton. Cell Signal 14:723–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Horsch K, Schaller MD, Hynes NE. 2001. The protein tyrosine phosphatase-PEST is implicated in the negative regulation of epidermal growth factor on PRL signaling in mammary epithelial cells. Mol Endocrinol 15:2182–2196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hunter S, Koch BL, Anderson SM. 1997. Phosphorylation of cbl after stimulation of Nb2 cells with prolactin and its association with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Mol Endocrinol 11:1213–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Goh EL, Zhu T, Leong WY, Lobie PE. 2002. c-Cbl is a negative regulator of GH-stimulated STAT5-mediated transcription. Endocrinology 143:3590–3603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wang L, Rudert WA, Loutaev I, Roginskaya V, Corey SJ. 2002. Repression of c-Cbl leads to enhanced G-CSF Jak-STAT signaling without increased cell proliferation. Oncogene 21:5346–5355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Rivero-Lezcano OM, Sameshima JH, Marcilla A, Robbins KC. 1994. Physical association between Src homology 3 elements and the protein product of the c-cbl proto-oncogene. J Biol Chem 269:17363–17366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Wunderlich L, Gohér A, Faragó A, Downward J, Buday L. 1999. Requirement of multiple SH3 domains of Nck for ligand binding. Cell Signal 11:253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Sitko JC, Guevara CI, Cacalano NA. 2004. Tyrosine-phosphorylated SOCS3 interacts with the Nck and Crk-L adapter proteins and regulates Nck activation. J Biol Chem 279:37662–37669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Tomic S, Chughtai N, Ali S. 1999. SOCS-1, -2, -3: selective targets and functions downstream of the prolactin receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol 158:45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Dif F, Saunier E, Demeneix B, Kelly PA, Edery M. 2001. Cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein suppresses PRL signaling by binding the PRL receptor. Endocrinology 142:5286–5293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Sasaki A, Yasukawa H, Shouda T, Kitamura T, Dikic I, Yoshimura A. 2000. CIS3/SOCS-3 suppresses erythropoietin (EPO) signaling by binding the EPO receptor and JAK2. J Biol Chem 275:29338–29347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Herber B, Truss M, Beato M, Müller R. 1994. Inducible regulatory elements in the human cyclin D1 promoter. Oncogene 9:2105–2107 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Diakonova M, Gunter DR, Herrington J, Carter-Su C. 2002. SH2-Bβ is a Rac-binding protein that regulates cell motility. J Biol Chem 277:10669–10677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. O'Brien KB, Argetsinger LS, Diakonova M, Carter-Su C. 2003. YXXL motifs in SH2-Bβ are phosphorylated by JAK2, JAK1, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor and are required for membrane ruffling. J Biol Chem 278:11970–11978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Meyer DJ, Campbell GS, Cochran BH, Argetsinger LS, Larner AC, Finbloom DS, Carter-Su C, Schwartz J. 1994. Growth hormone induces a DNA binding factor related to the interferon-stimulated 91-kDa transcription factor. J Biol Chem 269:4701–4704 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]