Abstract

Background

Hysterectomy is among the more common surgical procedures in gynecology. The aim of this study was to calculate population-wide rates of hysterectomy across Germany and to obtain information on the different modalities of hysterectomy currently performed in German hospitals. This was done on the basis of nationwide DRG statistics (DRG = diagnosis-related groups) covering the years 2005–2006.

Methods

We analyzed the nationwide DRG statistics for 2005 and 2006, in which we found 305 015 hysterectomies. Based on these data we calculated hysterectomy rates for the female population. We determined the indications for each hysterectomy with an algorithm based on the ICD-10 codes, and we categorized the operations on the basis of their OPS codes (OPS = Operationen- und Prozedurenschlüssel [Classification of Operations and Procedures]).

Results

The overall rate of hysterectomy in Germany was 362 per 100 000 person-years. 55% of hysterectomies for benign diseases of the female genital tract were performed transvaginally. Bilateral ovariectomy was performed concomitantly in 23% of all hysterectomies, while 4% of all hysterectomies were subtotal. Hysterectomy rates varied considerably across federal states: the rate for benign disease was lowest in Hamburg (213.8 per 100 000 women per year) and highest in Mecklenburg–West Pomerania (361.9 per 100 000 women per year).

Conclusion

Hysterectomy rates vary markedly from one region to another. Moreover, even though recent studies have shown that bilateral ovariectomy is harmful to women under 50 who undergo hysterectomy for benign disease, it is still performed in 4% of all hysterectomies for benign indications in Germany.

In many countries hysterectomy is among the more common surgical procedures in gynecology. In Germany, for example, around 153 000 hysterectomies were carried out in 2006 (1). The frequency of hysterectomy varies widely from region to region (2– 7) and over the course of time (2, 7– 9). Hysterectomy rates are affected not only by the incidence of relevant diseases but also by a number of other factors. These include:

Availability of gynecologists and of surgical and non-surgical treatments

Number of hospital beds per unit of population

Type of health insurance

Sex of treating gynecologist

Patients’ knowledge of treatment options (12)

Cultural norms regarding fertility-preserving treatment.

Interestingly, the increasing prevalence of obesity also influences rates of hysterectomy, because obese women are at higher risk of bleeding and infections during and after hysterectomy (13, 14). The populationwide hysterectomy rate may serve as an indicator of the healthcare status of women with gynecological diseases in Germany.

Since 2004 the remuneration of German hospitals for treatment of inpatients has been regulated by means of a system of diagnosis-related groups (DRG). With very few exceptions (treatment in a small number of psychiatric and psychotherapeutic units, treatment of soldiers in army hospitals, treatment in prison hospitals), all individual inpatient stays, including the diagnosis and procedure codes, are entered in the nationwide DRG database. The first epidemiological studies based on DRG statistics have recently been published for an international readership (15– 18). Since day-surgery hysterectomy is rare in Germany, the DRG data accurately reflect the rates of hysterectomy in this country (19). Given that hospitals cannot be reimbursed for operations outside the DRG system, it can be assumed that all hysterectomies carried out were also documented.

The goal of this study, based on the nationwide DRG statistics for 2005 and 2006, was to determine the populationwide hysterectomy rates and the frequencies of the different types of hysterectomy performed in hospitals in Germany.

Materials and methods

Invoicing by DRG became legally compulsory for German hospitals in 2004 with the passage of a law regulating reimbursement for inpatient treatment. Hospitals are obliged by law to transmit their data annually to the Institute for the Hospital Remuneration System (InEK). After testing for plausibility, InEK passes the anonymized hospital data to the Federal Statistical Office (FSO). The FSO provides the DRG data from 2005 onward for the purposes of scientific study. We chose to analyze the figures for the treatment years 2005 and 2006 (total 17.4 million inpatient stays by women). At the end of each inpatient stay, ICD-10 codes (e1, e2) for one primary diagnosis and up to 89 subsidiary diagnoses can be assigned. Furthermore, up to 100 procedures can be coded according to the OPS (Operationen- und Prozedurenschlüssel [Classification of Operations and Procedures]) (e3, e4).

We identified hysterectomy operations by the OPS coding:

5–682 (subtotal hysterectomy)

5–683 (total hysterectomy)

5–685 (radical hysterectomy).

A total of 307 230 hysterectomies were carried out. Of these operations, 2215 (0.7%) were excluded from analysis because the patient’s place of residence was outside Germany (1645, 0.5%), unknown (249, 0.1%), or the patient was homeless (321, 0.1%). Thus all final analyses covered 305 015 hysterectomies. A hierarchical diagnostic algorithm often used and described in the international literature (3, 18, 20) was employed to define six groups of indications for hysterectomy based on principal and subsidiary diagnoses:

Group 1: Malignant neoplasms of the female genital organs (ICD-10: C53 malignant neoplasm of the cervix uterini; C54–C55 malignant neoplasms of uterus; C56 malignant neoplasm of ovary; C57 malignant neoplasm of other or unspecified female genital organs; C58 malignant neoplasm of placenta)

Group 2: Endometrial adenomatous hyperplasia (ICD-10: N85.1)

Group 3: Carcinoma in situ of cervix uteri (ICD-10: D06), endometrium (ICD-10: D07.0), or other and unspecified female genital organs (D07.3)

Group 4: Neoplasm of uncertain or unknown behaviour of female genital organs (ICD-10: D39)

Group 5: Malignant primary tumors other than those in group 1 (e.g., hysterectomy because of debulking of colorectal carcinoma or urothelial carcinoma)

Group 6: Benign diseases of the female genital tract (for detail see [18]).

Overall, 99% of the hysterectomy procedures were characterized by a single ICD-10 code. The remaining 2981 operations were manually assigned to one of the types of hysterectomy. The following surgical approaches were distinguished:

Open abdominal hysterectomy

Vaginal hysterectomy

Laparoscopic hysterectomy

Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH)

Vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy with conversion to open abdominal hysterectomy.

Moreover, with the aid of the OPS codes subtotal hysterectomy could be distinguished from total hysterectomy and from hysterectomy with and without bilateral salpingo-ovariectomy (hereinafter referred to as ovariectomy) (for details of OPS codes see [18]).

Statistical methods

We calculated crude, age-specific, and age-standardized hysterectomy rates (number of hysterectomies per 100 000 person-years). The denominator of the rates was the mean annual population. The standard age was derived from the population of the Federal Republic of Germany (women only) on December 31, 2005. Because the rates for 2005 and 2006 were practically identical, we report only findings for the study period as a whole. Weighted coefficients of variation were calculated to describe the variability of hysterectomy rates across the 16 federal states.

The technicity index is the proportion of all hysterectomies comprised by laparoscopic (including LAVH) and vaginal procedures. This index has been used in France, for example, to compare different hospitals (e5). Laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy directly converted to open abdominal hysterectomy in the same session was counted as open abdominal hysterectomy. The software SAS 9.2 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

The hysterectomy rate in Germany in the years 2005 and 2006 was 362 per 100 000 person-years (3.6 per 1000 person-years). The commonest procedures were vaginal hysterectomy and abdominal hysterectomy. The type of procedure depended on the indication. In benign diseases of the female genital organs around 55% of hysterectomies were via the vaginal route. The highest proportion of vaginal hysterectomies was in the operations for carcinoma in situ of the female genital organs (67.4%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Hysterectomy in Germany, 2005–2006: types of operation and indications.

| Indications for hysterectomy (%) | |||||||

| Type of operation | Hyster‧ectomies (n) | Malignant neoplasms of female genital organs | Endometrial adenomatous hyperplasia | Carcinoma in situ of female genital organs | Neoplasias of uncertain or unknown behaviour | Other ‧malignant primary ‧tumors | Benign diseases of female ‧genital ‧organs |

| Abdominal ‧hysterectomy | 120 485 | 88.7 | 39.0 | 22.5 | 75.0 | 86.7 | 31.3 |

| LAVH | 17 090 | 2.3 | 9.1 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 1.0 | 6.0 |

| Laparoscopic ‧hysterectomy | 14 967 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 3.8 | 0.5 | 5.8 |

| Laparoscopic ‧hysterectomy, ‧conversion to abdominal hysterectomy | 1707 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy, conversion to abdominal hysterectomy | 1616 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 144 628 | 5.5 | 47.4 | 67.4 | 11.7 | 3.6 | 54.5 |

| Unclear or missing data | 4522 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 7.7 | 1.3 |

| Total | 305 015 | 12.1 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 81.4 |

Including subtotal and total hysterectomies; LAVH, laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy

The technicity index for benign diseases of the female genital organs was 67.1% for Germany as a whole. In contrast, the technicity index for malignant neoplasms of the female genital organs was only 8.7% nationwide (data not shown).

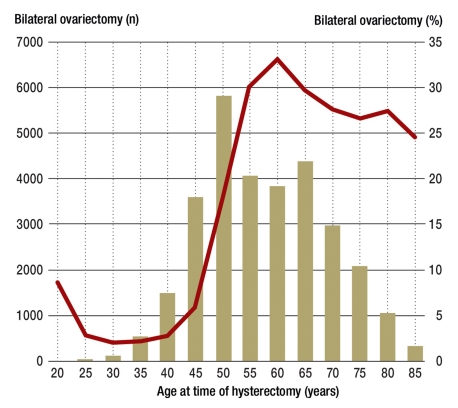

Overall, 23% of hysterectomies were accompanied by concomitant bilateral ovariectomy. The latter was particularly common among operations for carcinoma in situ of the female genital organs and for endometrial adenomatous hyperplasia. In hysterectomy for benign diseases of the female genital organs the rate of bilateral ovariectomy was 12% for all age groups together, but depended strongly on age: In women under 50 the rate was only 4%, compared with 26% in those aged 50 or more (Table 2, Figure).

Table 2. Subtotal and total hysterectomies. and relative frequency of bilateral ovariectomy accompanying hysterectomy in ?Germany, 2005–2006.

| Indication group (ICD-10 codes) | Hyster‧ectomies (n) | Category of hysterectomy (%) | Bilateral ovariectomy (%) | ||||

| Subtotal | Total | No data | No | Yes | No data | ||

| Malignant neoplasms of female ‧genital organs (C53–C58) | 37 037 | 0.65 | 99.33 | 0.02 | 85.37 | 12.86 | 1.77 |

| Endometrial adenomatous hyperplasia (N85.1) | 5063 | 1.15 | 98.85 | 0.00 | 40.04 | 59.29 | 0.67 |

| Carcinoma in situ of female genital organs (D06, D07.0, D07.3) | 6337 | 0.14 | 99.86 | 0.00 | 14.17 | 84.95 | 0.88 |

| Neoplasm of uncertain or unknown behav‧iour of female genital organs (D39) | 5646 | 3.38 | 96.62 | 0.00 | 54.27 | 44.00 | 1.74 |

| Other malignant primary tumors | 2712 | 3.17 | 96.83 | 0.00 | 67.88 | 26.25 | 5.86 |

| Benign diseases of female genital organs | 248 220 | 4.75 | 95.24 | 0.00 | 86.55 | 12.21 | 1.24 |

| Total | 305 015 | 4.06 | 95.93 | 0.01 | 75.79 | 22.87 | 1.34 |

eFigure.

Regional age-standardized hysterectomy rates (per 100 000) in Germany, 2005–2006

Subtotal hysterectomy was carried out in 4.06% of cases. The proportion of subtotal hysterectomy was highest in operations for benign diseases of the female genital organs (4.75%) and lowest for malignant neoplasms of the female genital organs (0.65%). The relative frequency of subtotal hysterectomy depended on the route of access. Some 62.32% of laparoscopic hysterectomies involved subtotal resection. Similar relative frequencies were found among hysterectomies for benign diseases of the female genital organs (Table 3).

Table 3. Subtotal and total hysterectomies by type of operation in Germany, 2005–2006.

| Type of operation | All hysterectomies | Hysterectomies for benign diseases of female genital organs | ||||

| Hysterectomies (n) | Subtotal (%) | Total (%) | Hysterectomies (n) | Subtotal (%) | Total (%) | |

| Abdominal hysterectomy | 120 485 | 2.08 | 97.92 | 77 638 | 2.75 | 97.25 |

| LAVH | 17 090 | 0.87 | 99.13 | 14 975 | 0.97 | 99.03 |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy | 14 967 | 62.32 | 37.68 | 14 271 | 64.10 | 35.90 |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy with conversion | 1707 | 13.59 | 86.41 | 1 498 | 14.95 | 85.05 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy with ‧conversion | 1616 | 1.98 | 98.02 | 1 440 | 2.22 | 97.78 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 144 628 | 0.04 | 99.96 | 135 154 | 0.04 | 99.96 |

| Unclear or missing data | 4 522 | 1.80 | 98.20 | 3 244 | 1.76 | 97.87 |

| Total | 305 015 | 4.06 | 95.93 | 248 220 | 4.75 | 95.24 |

Conversion, conversion to open abdominal hysterectomy; LAVH, laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy

The hysterectomy rates showed distinct regional variations. Hysterectomy for benign diseases of the female genital organs was least frequent in Hamburg (213.8 per 100 000 person-years) and most frequent in Mecklenburg–West Pomerania (361.9 per 100 000 person-years). Hysterectomy for carcinoma in situ of the female genital organs displayed the greatest relative regional variability, with the lowest rate in Hamburg (5.3 per 100 000 person-years) and the highest in the Saarland (11.6 per 100 000 person-years). The least regional variability was shown by hysterectomy for malignant neoplasms of the female genital organs (range 41.8 to 47.7 per 100 000 person-years) (Table 4, eFigure). The technicity index for hysterectomy carried out because of benign diseases of the female genital organs varied regionally from 61.4% (Hamburg) to 79.3% (Berlin) (data not shown).

Table 4. Age-standardized hysterectomy rates (per 100 000) in the federal states of Germany, 2005–2006.

| Indication group (%) | ||||||||

| State | Female ‧population*1(n) | Overall hysterectomy rate (%) | Malignant ‧neoplasms of female genital organs | Endometrial adenomatous hyperplasia | Carcinoma in situ of female genital organs | Neoplasms of uncertain or unknown ‧behaviour | Other malig‧nant primary tumors | Benign diseases of ‧female genital organs |

| SH | 1 447 665 | 350.7 | 41.8 | 4.1 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 2.6 | 288.1 |

| HH | 894 160 | 278.5 | 47.6 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 3.1 | 213.8 |

| NS | 4 075 988 | 374.2 | 42.4 | 5.0 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 3.4 | 309.7 |

| HB | 341 989 | 295.8 | 47.7 | 3.2 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 3.1 | 228.5 |

| NW | 9 260 917 | 369.1 | 41.9 | 6.1 | 7.8 | 6.7 | 3.7 | 302.9 |

| HE | 3 109 204 | 361.8 | 43.6 | 4.8 | 7.3 | 6.0 | 3.1 | 296.9 |

| RP | 2 068 595 | 412.7 | 43.3 | 6.5 | 11.0 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 341.0 |

| BW | 5 464 795 | 328.7 | 44.3 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 6.3 | 2.8 | 263.4 |

| BY | 6 366 071 | 346.9 | 46.5 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 3.3 | 279.7 |

| SL | 539 934 | 394.4 | 42.7 | 3.6 | 11.6 | 6.2 | 4.7 | 325.7 |

| BE | 1 735 546 | 287.9 | 44.8 | 4.3 | 9.6 | 6.7 | 3.0 | 219.5 |

| BB | 1 292 551 | 408.9 | 44.6 | 8.9 | 9.6 | 7.9 | 2.9 | 334.9 |

| MV | 861 049 | 435.5 | 43.9 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 10.0 | 2.0 | 361.9 |

| SN | 2 190 514 | 393.6 | 47.1 | 7.3 | 8.8 | 8.3 | 3.3 | 318.9 |

| ST | 1 263 996 | 382.1 | 44.1 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 7.8 | 3.2 | 309.2 |

| TH | 1 185 060 | 417.8 | 46.1 | 6.7 | 10.6 | 7.0 | 2.9 | 344.5 |

| Range*2 | 157.0 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 2.7 | 148.1 | |

| Minimum | 278.5 | 41.8 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 2.0 | 213.8 | |

| Maximum | 435.5 | 47.7 | 9.2 | 11.6 | 10.0 | 4.7 | 361.9 | |

| wCV%*3 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 5.4 | 5.6 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 2.7 | |

| FRG | 42 098 034 | 362.4 | 44.0 | 6.0 | 7.5 | 6.7 | 3.2 | 294.9 |

Age standard: female population of Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) on December 31, 2005; BB = Brandenburg, BE = Berlin, BW = Baden-Württemberg, BY = Bavaria, HB = Bremen, HE = Hesse, HH = Hamburg, MV = Mecklenburg–West Pomerania, NS = Lower Saxony, NW = North Rhine–Westphalia, RP = Rheinland-Palatinate, SH = Schleswig-Holstein, SL = Saarland, SN = Saxony, ST = Saxony-Anhalt, TH = Thuringia;

*1 female population on December 31, 2005;

*2 range: maximal minus minimal rate per 100 000 person-years;

*3 weighted coefficient of variation with respective population size as weight

Discussion

The rate of hysterectomy for benign diseases of the female genital organs in Germany (3.6 per 1000 person-years) is higher than in Sweden (2.1 per 1000 person-years) (9) and lower than in the USA (4.9 per 1000 person-years) and Australia (5.4 per 1000 person-years) (3, 7). The comparability of hysterectomy rates in various countries is limited, however, by differences among studies with regard to age standardization of rates, study periods, and selection criteria for the study population. Like many other countries (2, 7– 9), Germany shows distinct inter-regional differences in hysterectomy rates. The analyses presented here do not permit conclusions as to the reasons for these differences, because the DRG statistics do not include important parameters such as disease-related circumstances, physician- or hospital-related factors, rates of participation in cancer screening programs, and patient preferences.

In cases of genital prolapse without uterine pathology, one should first explore the options for conservative treatment or uterus-sparing surgery (fixation of uterus or vagina) before considering hysterectomy (S1 guideline on genital prolapse [e6]). Hysterectomy is viewed as the most effective treatment for uterine adenomyosis in women who no longer wish to become pregnant. Those who still want children or prefer to preserve the uterus should initially be treated by means of interventional radiology procedures such as embolization and MRI-guided focused ultrasonographic ablation as part of a study, if at all possible. Alternatives to hysterectomy include gestagens, hormonal contraceptives, and levonorgestrel intrauterine systems (S2 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis [e8]). In women with heavy menstrual bleeding, hysterectomy should be considered only when other treatment options have failed, are contraindicated, or are refused by the patient, or when the patient expressly requests hysterectomy (NICE guideline [e8]). Myomectomy and uterine artery embolization are viewed as safe and effective alternatives to hysterectomy in patients with symptomatic leiomyoma (guideline of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [e9]).

A Cochrane review of 34 randomized studies that compared various endpoints following abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal hysterectomy revealed that vaginal hysterectomy is the surgical procedure of choice for benign diseases of the female genital organs, because it involves the least risk and shows the greatest cost effectiveness (e10). Vaginal hysterectomies formed 55% of the hysterectomies for benign diseases of the female genital organs in Germany in 2005–2006, a far higher proportion than, for example, in the USA in 2003 (22%) (e11).

The proportion of subtotal hysterectomies for benign diseases of the female genital organs in Germany in 2005–2006 was around 5%, much lower than in Denmark in 1998 (22%) (13). Merrill reported that around 6% of the 3.1 million hysterectomies carried out for benign diseases of the female genital organs in the USA in the period 2001–2005 were subtotal abdominal procedures (3). Because they are still at risk of cervical carcinoma (e12), women treated by subtotal hysterectomy should continue to attend regularly for cancer screening (for example, see e13]).

The DRG database does not permit clear medical classification of menopausal status. Using age ≥50 as the definition of (peri)menopausal or postmenopausal status, 26% of women in this category treated by hysterectomy had concomitant bilateral ovariectomy. In women under 50, the proportion was only 4%. Whiteman et al. found that in 2000–2004, 37% of all women in the USA who underwent hysterectomy for benign diseases of the female genital organs also had bilateral ovariectomy (2). The corresponding proportion in Germany is far lower, at 3%.

The results of the largest prospective cohort study to establish the long-term consequences of bilateral ovariectomy in comparison with ovarian conservation in hysterectomy for benign diseases of the female genital organs were published not long ago: In the Nurses’ Health Study (29 380 nurses, duration of follow-up 24 years), Parker et al. found that, particularly in women <50, bilateral ovariectomy carried out concomitantly with hysterectomy lowers both the risk of and mortality from breast cancer and ovarian carcinoma, but is associated with a higher risk of coronary heart disease, cerebral insult, and, surprisingly, bronchial carcinoma. Altogether, this study showed higher overall mortality (particularly from coronary heart disease and bronchial carcinoma) with bilateral ovariectomy than with preservation of the ovaries (21). A recently published Swedish study confirmed the increased risk for coronary heart disease and cerebral insult in women <50 who undergo bilateral ovariectomy (22). The meta-analysis by Atsma et al. also showed an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease after bilateral ovariectomy in younger women (23).

Although the present study probably paints a representative picture of hysterectomy in Germany in 2005 and 2006, it does have some limitations. The analysis was based on the codes assigned to diagnoses and procedures; however, these codes do not always fully reflect the often complex constellations of symptoms and diagnoses that lead to the decision to perform hysterectomy (24). The data do not, for example, permit analysis of the precise clinical reasons for deciding to carry out subtotal hysterectomy, concomitant bilateral ovariectomy, or open abdominal hysterectomy.

Furthermore, the data analyzed are for treatments carried out in 2005 and 2006. More widespread availability of non-surgical treatment options and minimally invasive techniques in the ensuing years may have changed the rates of hysterectomy in Germany.

Moreover, InEK’s quality control of the DRG data supplied to us was not thorough enough to enable us to validate the coding of the diagnoses and procedures. The anonymization of the DRG data rules out any validation by comparing the assigned codes with a representative sample of patients’ case notes. DRG validation studies at particular hospitals would also be of no assistance, for two reasons: first, they would not be representative of the population as a whole, and second, routine documentation in hospitals cannot necessarily be seen as the gold standard for validation. Therefore, the plausibility of our findings has to be critically considered in light of existing clinical and epidemiological knowledge and other data.

Comparison of the relative frequency of organ damage in hysterectomy (1.4% of 149 456 operations) in the BQS report of 2006 (25) with that of the coded complication of perforation (ICD-10: T81.2, unintentional perforation of a blood vessel, nerve, or organ during an intervention) in the DRG data set (1.1%) shows great similarity. Plausibly from the clinical point of view, complications (ICD-10: T81.0–T81.4) were coded much more frequently for conversion from vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy to open abdominal hysterectomy than for hysterectomy that did not require conversion. Another way of assessing the quality of the DRG data would be to compare them with data from other sources. Such a comparison was recently performed for testicular tumors, showing excellent agreement between population-based cancer registries and the DRG data (16).

Conclusion

The overall rate of hysterectomy in Germany in the years 2005 and 2006 was 362 per 100 000 person-years. Different regions of the country differ considerably in their hysterectomy rates. Bilateral ovariectomy, carried out in 4% of hysterectomies for benign diseases of the female genital organs in women under 50, has negative consequences according to recent studies.

FIGURE.

Hysterectomy with bilateral ovariectomy for benign diseases of the female genital organs in Germany, 2005–2006; columns: Absolute number (n) of women treated by hysterectomy with bilateral ovariectomy; curve: proportion (%) of hysterectomies with simultaneous bilateral ovariectomy. Altogether, 30 310 (12.36%) of 245 132 hysterectomies for which the ovariectomy status was clearly coded were accompanied by bilateral ovariectomy

Key Messages.

The rate of hysterectomy (all indications) in Germany in 2005 and 2006 was 362 per 100 000 person-years.

The proportion of vaginal hysterectomies for benign diseases of the female genital organs was 55%.

Concomitant bilateral ovariectomy was performed in 23% of all hysterectomies and in 12% of hysterectomies for benign diseases of the female genital organs.

Subtotal hysterectomies comprised 4% of all hysterectomies.

The rates of hysterectomy for benign diseases of the female genital organs in the individual federal states varied between 213.8 (Hamburg) and 361.9 (Mecklenburg–West Pomerania) per 100 000 person-years.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Footnotes

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Statistisches Bundesamt. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 2009. Fallpauschalenbezogene Krankenhausstatistik (DRG-Statistik): Operationen und Prozeduren der vollstationären Patientinnen und Patienten in Krankenhäusern - Ausführliche Darstellung. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:34–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merrill RM. Hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 1997 through 2005. Med Sci Monit. 2008;14:CR24–CR31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roos NP. Hysterectomy: variations in rates across small areas and across physicians’ practices. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:327–335. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.4.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McPherson K, Wennberg JE, Hovind OB, Clifford P. Small-area variations in the use of common surgical procedures: an international comparison of New England, England, and Norway. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1310–1314. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198211183072104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keskimaki I, Aro S, Teperi J. Regional variation in surgical procedure rates in Finland. Scand J Soc Med. 1994;22:132–138. doi: 10.1177/140349489402200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spilsbury K, Semmens JB, Hammond I, Bolck A. Persistent high rates of hysterectomy in Western Australia: a population-based study of 83 000 procedures over 23 years. BJOG. 2006;113:804–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vuorma S, Teperi J, Hurskainen R, et al. Hysterectomy trends in Finland in 1987-1995—a register based analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1998;77:770–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundholm C, Forsgren C, Johansson AL, et al. Hysterectomy on benign indications in Sweden 1987-2003: a nationwide trend analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:52–58. doi: 10.1080/00016340802596017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domenighetti G, Luraschi P, Marazzi A. Hysterectomy and sex of the gynecologist. N Engl J Med. 1985;313 doi: 10.1056/NEJM198512053132320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domenighetti G, Casabianca A. Rate of hysterectomy is lower among female doctors and lawyers’ wives. BMJ. 1997;314 doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7091.1417a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Domenighetti G, Luraschi P, Casabianca A, et al. Effect of information campaign by the mass media on hysterectomy rates. Lancet. 1988;2:1470–1473. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90943-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gimbel H, Settnes A, Tabor A. Hysterectomy on benign indication in Denmark 1988-1998 A register based trend analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:267–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Settnes A, Jorgensen T, Lange AP. Hysterectomy in Danish women: weight-related factors, psychologic factors, and life-style variables. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00107-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stang A, Stausberg J. Inpatient management of patients with skin cancer in Germany: an analysis of the nationwide DRG-statistic 2005-2006. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(Suppl 3):99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stang A, Katalinic A, Dieckmann KP, et al. A novel approach to estimate the German-wide incidence of testicular cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. 2010;34:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stang A, Weichenthal M. Micrographic surgery of skin cancer in German hospitals 2005-2006. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011:422–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stang A, Merrill RM, Kuss O. Nationwide rates of conversion from laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy to open abdominal hysterectomy in Germany. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26:125–133. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9543-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salfelder A, Lueken RP, Gallinat A, et al. Hysterektomie als Standardeingriff in der Tagesklinik - ein Wagnis? Frauenarzt. 2007;48:954–958. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keshavarz H, Hillis SD, Kieke BA. Hysterectomy surveillance - United States, 1994-1999. MMWR. 2002;51(SS05):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker WH, Broder MS, Chang E, et al. Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy and long-term health outcomes in the nurses’ health study. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1027–1037. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a11c64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingelsson E, Lundholm C, Johansson AL, Altman D. Hysterectomy and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:745–750. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atsma F, Bartelink ML, Grobbee DE, van der Schouw YT. Postmenopausal status and early menopause as independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Menopause. 2006;13:265–279. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000218683.97338.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brett KM, Marsh JV, Madans JH. Epidemiology of hysterectomy in the United States: demographic and reproductive factors in a nationally representative sample. J Womens Health. 1997;6:309–316. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giesen C, Dabisch I BQS Bundesgeschäftsstelle Qualitätssicherung gGmbH. BQS-Qualitätsreport 2006 . Düsseldorf : BQS Bundesgeschäfsstelle Qualitätssicherung gGmbH; 2011. Kapitel 5 Gynäkologische Operationen; pp. 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- E1.ICD-10-GM 2005 Systematisches Verzeichnis Internationale statistische Klassifikation der Krankheiten und verwandter Gesundheitsprobleme, 10. Revision - German Modification. Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag. Köln: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- E2.ICD-10-GM 2006 Systematisches Verzeichnis Internationale statistische Klassifikation der Krankheiten und verwandter Gesundheitsprobleme. 10. Revision - German Modification. Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag. Köln: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- E3.OPS 2005 Systematisches Verzeichnis. Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag. Köln: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- E4.OPS 2006 Systematisches Verzeichnis. Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag. Köln: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- E5.Laberge PY, Singh SS. Surgical approach to hysterectomy: introducing the concept of technicity. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;3:1050–1053. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34350-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG), Arbeitsgemeinschaft, Urogynäkologie und Plastische Beckenbodenrekonstruktion (AGUB), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie (DGU), Arbeitsgemeinschaft Urogynäkologie und rekonstruktive Beckenbodenchirurgie (AUB, Österreich), Österreichische Gesellschaft für Urologie, Arbeitsgemeinschaft Urogynäkologie (AUG, Schweiz) Descensus genitalis der Frau - Diagnostik und Therapie AWMF-Leitlinien-Register Nr. 015/006. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/015-006_S1IDA_Descensus_genitalis_der_ Frau_06-2008_09-2012.pdf. 2011. May 2, Accessed on.

- E7.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG), Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (SGGG), Österreichische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe e.V. (OEGGG), Stiftung Endometriose-Forschung (SEF), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie e.V., Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie e.V., Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologische Endokrinologie und Fortpflanzungsmedizin e.V., Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Gynäkologische Onkologie (AGO) e.V. der DGGG, Endometriose-Vereinigung Deutschland e. V., Österreichische Endometriose Vereinigung e.V. Diagnostik und Therapie der Endometriose AWMF-Leitlinien-Register Nr. 015/045. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/015-045_S1_Diagnostik_ und_Therapie_der_Endometriose_05-2010_05-2015.pdf. 2011. May 2, Accessed on.

- E8.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE clinical guideline 44. Heavy menstrual bleeding. London National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2007. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG44NICEGuideline.pdf. 2011. May 2, Accessed on.

- E9.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. ACOG practice bulletin, no. 96. Washington (DC): 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003677.pub4. CD003677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Wu JM, Wechter ME, Geller EJ, et al. Hysterectomy rates in the United States, 2003. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1091–1095. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000285997.38553.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Storm HH, Clemmensen IH, Manders T, Brinton LA. Supravaginal uterine amputation in Denmark 1978-1988 and risk of cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;45:198–201. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90285-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (DGGG), Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Endoskopie (AGE): Die laparoskopische suprazervikale Hysterektomie (LASH). AWMF-Leitlinien-Register Nr. 015/06. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/ 015-064_S1_Die_laparoskopische_suprazervikale_Hysterektomie__ LASH__03-2008_09-2012.pdf. 2011 May 2; accessed on. [Google Scholar]