Abstract

Cannabinoids are promising medicines to slow down disease progression in neurodegenerative disorders including Parkinson's disease (PD) and Huntington's disease (HD), two of the most important disorders affecting the basal ganglia. Two pharmacological profiles have been proposed for cannabinoids being effective in these disorders. On the one hand, cannabinoids like Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol or cannabidiol protect nigral or striatal neurons in experimental models of both disorders, in which oxidative injury is a prominent cytotoxic mechanism. This effect could be exerted, at least in part, through mechanisms independent of CB1 and CB2 receptors and involving the control of endogenous antioxidant defences. On the other hand, the activation of CB2 receptors leads to a slower progression of neurodegeneration in both disorders. This effect would be exerted by limiting the toxicity of microglial cells for neurons and, in particular, by reducing the generation of proinflammatory factors. It is important to mention that CB2 receptors have been identified in the healthy brain, mainly in glial elements and, to a lesser extent, in certain subpopulations of neurons, and that they are dramatically up-regulated in response to damaging stimuli, which supports the idea that the cannabinoid system behaves as an endogenous neuroprotective system. This CB2 receptor up-regulation has been found in many neurodegenerative disorders including HD and PD, which supports the beneficial effects found for CB2 receptor agonists in both disorders. In conclusion, the evidence reported so far supports that those cannabinoids having antioxidant properties and/or capability to activate CB2 receptors may represent promising therapeutic agents in HD and PD, thus deserving a prompt clinical evaluation.

LINKED ARTICLES

This article is part of a themed issue on Cannabinoids in Biology and Medicine. To view the other articles in this issue visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2011.163.issue-7

Keywords: basal ganglia, cannabinoid signalling system, cannabinoids, CB1 receptors, CB2 receptors, Huntington's disease, neurodegeneration, neuroprotection, Parkinson's disease

The cannabinoid signalling system and the pathophysiology of the basal ganglia

Trying to elucidate the mechanisms of action of cannabinoids, the active constituents of the plant Cannabis sativa, Mechoulam and many other colleagues discovered in late 1980s and early 1990s the so-called cannabinoid system, a novel intercellular signalling system particularly active in the central nervous system (CNS) (see Chevaleyre et al., 2006; Kano et al., 2009 for reviews). Most of the elements that constitute this signalling system have been already identified and characterized (see Di Marzo, 2009; Pertwee et al., 2010, for review), and, more importantly, they have been found to be altered in numerous pathologies, either in the CNS or in the periphery (Di Marzo, 2008; Martínez-Orgado et al., 2009), which explains the proposed therapeutic potential of certain cannabinoid compounds in these disorders (Janero and Makriyannis, 2009; Pertwee, 2009). Presently, the cannabinoid signalling system represents an important field of study for the development of novel therapeutic agents with properties for symptom relief or control of disease progression in numerous CNS pathologies including chronic pain, feeding disorders, addictive states, movement disorders, brain tumours and others (Bahr et al., 2006). Novel cannabinoid-based medicines have been recently approved for specific pathologies such as multiple sclerosis (Wright, 2007; Pertwee, 2009), whereas various clinical studies with these preparations are presently underway and should lead to novel indications over the next few years.

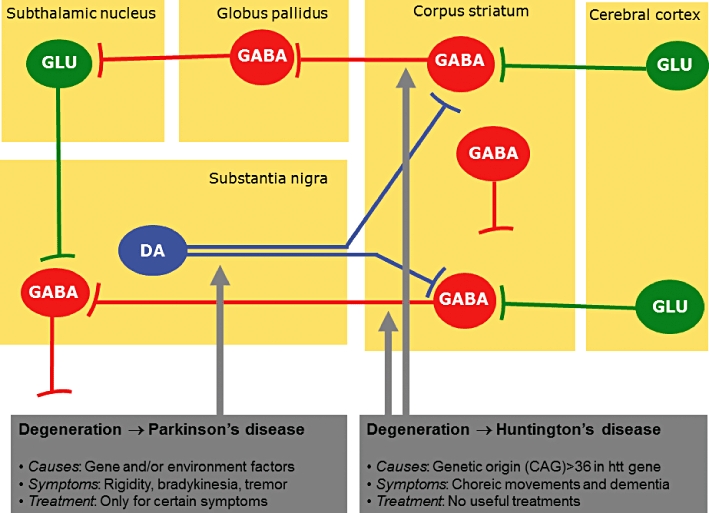

Basal ganglia disorders, mainly Parkinson's disease (PD) and Huntington's disease (HD) (an overview on the basal ganglia circuitry and its main pathologies can be seen in Figure 1), are included in the group of illnesses that may benefit from the use of cannabinoid-based medicines. HD is an inherited neurodegenerative disorder caused by a mutation in the gene encoding the protein huntingtin. The mutation consists of a CAG triplet repeat expansion translated into an abnormal polyglutamine tract in the amino-terminal portion of huntingtin, which due to a gain of function becomes toxic for specific striatal and cortical neuronal subpopulations, although a loss of function in mutant huntingtin has been also related to HD pathogenesis (see Zuccato et al., 2010 for review). Major symptoms include hyperkinesia (chorea) and cognitive deficits (see Roze et al., 2010 for review). PD is also a progressive neurodegenerative disorder whose aetiology has been, however, associated with environmental insults, genetic susceptibility or interactions between both causes (Thomas and Beal, 2007). The major clinical symptoms in PD are tremor, bradykinesia, postural instability and rigidity, symptoms that result from the severe dopaminergic denervation of the striatum caused by the progressive death of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta (Nagatsu and Sawada, 2007).

Figure 1.

Diagram showing the most important neuronal pathways involved in the basal ganglia function. The neuronal subpopulations that are affected in the two pathologies reviewed in this article, Huntington's disease and Parkinson's disease, are indicated by arrows. DA, dopamine; GABA, γ-aminobutiric acid; GLU, glutamate.

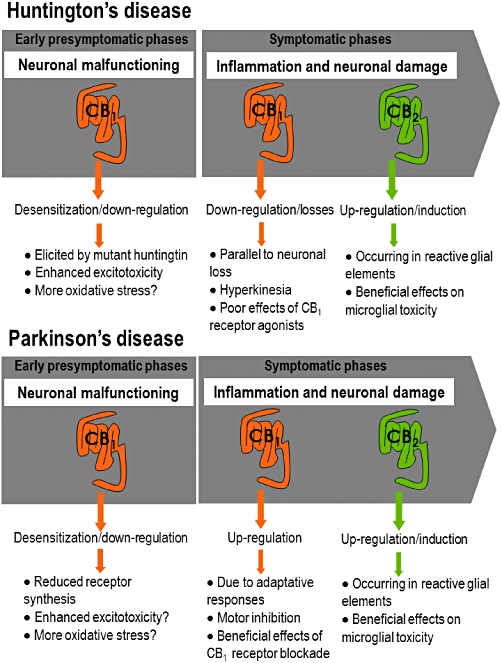

As mentioned above, both disorders could potentially receive significant benefits from the use of novel cannabinoid-based medicines. This is supported by the changes experienced during the progression of PD and HD by cannabinoid receptors, and also by other elements of the cannabinoid signalling system, all of them already identified in basal ganglia structures (reviewed in Fernández-Ruiz and González, 2005; Gerdeman and Fernández-Ruiz, 2008). These changes are summarized in Figure 2, and, in general, are compatible with the following three ideas:

Figure 2.

Comparison of CB1 and CB2 receptor changes during presymptomatic and symptomatic phases in experimental models of Huntington's disease and Parkinson's disease.

Early presymptomatic phases in both disorders characterized by neuronal malfunctioning rather than neuronal death, particularly in HD and also in PD, are associated with down-regulation/desensitization of CB1 receptors (Denovan-Wright and Robertson, 2000; Glass et al., 2000; Lastres-Becker et al., 2002a; Dowie et al., 2009; García-Arencibia et al., 2009a; Ferrer et al., 2010; Blázquez et al., 2011). Given that the activation of CB1 receptors inhibits glutamate release, one may expect that the down-regulation/desensitization of these receptors observed in both disorders is associated with enhanced glutamate levels and excitotoxicity, then playing an instrumental role and contributing to disease progression (Maccarrone et al., 2007; García-Arencibia et al., 2009b). In the case of HD, we recently demonstrated that CB1 receptor down-regulation is consequence of an inhibitory effect of mutant huntingtin on CB1 receptor gene promoter exerted through the repressor element 1 silencing transcription factor (Blázquez et al., 2011). On the other hand, some authors found that the enzyme that metabolizes endocannabinoids (mainly anandamide) called fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), was also defective in the cortices of presymptomatic HD patients (Battista et al., 2007). A reduction of FAAH activity is concordant with increased levels of endocannabinoids. However, the issue is controversial because FAAH mRNA expression was found to be increased in the striata of symptomatic R6/2 and R6/1 mice as well as in caudate-putamen samples from symptomatic HD patients (Blázquez et al., 2011), resulting in enhanced endocannabinoid metabolism and low levels of these endogenous compounds. This fact would be concordant with the reduction in CB1 receptors and would support the idea of a low endocannabinoid activity in HD.

Intermediate and advanced symptomatic phases, when neuronal death is the key event, are characterized by opposite changes in both disorders, with a profound loss of CB1 receptors in HD concomitant with death of CB1 receptor-containing striatal neurons, which is compatible with the hyperkinetic symptoms typical of these patients (reviewed in Pazos et al., 2008) and which has also been demonstrated in patients using in vivo imaging procedures (Van Laere et al., 2010). By contrast, a significant up-regulation of CB1 receptors was found in PD, which is caused by adaptive responses and is also compatible with the akinetic profile of these patients (García-Arencibia et al., 2009b, for review), although a few studies also described reductions (Hurley et al., 2003; Walsh et al., 2010).

Recent studies have also addressed the possible presence of the second cannabinoid receptor type, CB2, in the basal ganglia structures (reviewed in Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2007). This receptor, which is typical of immune tissues, has been found in the basal ganglia in a few neuronal subpopulations (Lanciego et al., 2011) but, in particular, in glial elements that become active during pathologies (Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2007). Thus, the activation of astrocytes and/or microglia, linked to neuronal injury in lesioned structures in HD and PD, has been associated with up-regulatory responses of CB2 receptors that are located in these cells and that would play protective roles by enhancing astrocyte-mediated positive effects and/or by reducing microglia-dependent toxic influences (Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2007, for review).

Therefore, these observations support the idea that both CB1 and CB2 receptors, as well as other elements of the cannabinoid signalling system, represent attractive targets for developing novel pharmacotherapies useful in PD and HD (and also other basal ganglia disorders as has been summarized in Table 1). Benefits that patients may receive from cannabinoid-based medicines would include first to be used as symptom-relieving substances, but also to serve as neuroprotective molecules able to slow down disease progression. The first of these two properties will be addressed only marginally in this review (see Table 1 for a summary of the most relevant effects), as this potential is based on the well-known motor effects of these compounds, for example, cannabinoid agonists inhibit motor activity, then they may be useful for HD, whereas cannabinoid antagonists produced the opposite effects, then they may be useful in PD (reviewed in Fernández-Ruiz and González, 2005; Fernández-Ruiz, 2009). These effects are the normal consequence of the important role exerted by the cannabinoid signalling system in regulating motor activity and the neurotransmitters involved in this function (Fernández-Ruiz and González, 2005; Marsicano and Lutz, 2006). Specific motor effects have been related to activation or blockade of CB1 receptors that are critically located in glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses within the basal ganglia circuitry (Gerdeman and Fernández-Ruiz, 2008). Based on these properties, several studies conducted in animal models addressed, for example, the potential of inhibitors of the endocannabinoid transporter to reduce hyperkinesia in HD (Lastres-Becker et al., 2002b; 2003;). A priori these compounds would act by enhancing the action of endocannabinoids at the CB1 receptor, but we assumed that these benefits would progressively disappear as soon as striatal projection neurons that contain CB1 receptors degenerate. In fact, Müller-Vahl et al. (1999) demonstrated that the CB1 receptor agonist nabilone, rather than improving hyperkinesia, enhanced choreic movements in patients. However, in our studies with animal models, we surprisingly observed that the effect of endocannabinoid transporter inhibitors was maintained even in cases of profound striatal degeneration (Lastres-Becker et al., 2003), and we found that these benefits, rather than derived from the activation of CB1 receptors, are related to the capability of these inhibitors to directly or indirectly (by elevating anandamide levels) activate the vanilloid TRPV1 receptors, which have been recently related to the control of basal ganglia function (see Fernández-Ruiz and González, 2005; Fernández-Ruiz, 2009, for review). In addition to hyperkinesia in HD, Parkinsonian tremor would be also susceptible to be reduced with CB1 receptor agonists given their inhibitory effects on subthalamonigral glutamatergic neurons (Sañudo-Peña and Walker, 1997), whereas bradykinesia may be reduced with CB1 receptor antagonists (Fernández-Espejo et al., 2005; González et al., 2006; Kelsey et al., 2009). However, these effects were not reproduced in most of studies conducted in patients (Consroe, 1998; Sieradzan et al., 2001; Carroll et al., 2004; Mesnage et al., 2004). A particular effect observed with cannabinoids in PD is the reduction of levodopa-induced dyskinesia because it was observed with CB1 receptor agonists but also with antagonists for this receptor, thus stressing the extreme complexity of the basal ganglia for cannabinoid effects (reviewed in Fabbrini et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Summary of effects observed with pharmacological manipulation of the cannabinoid system in basal ganglia disorders

| Neurological disorder | Symptom relieving effects | Effects on disease progression |

|---|---|---|

| Huntington's disease | –TRPV1 agonists reduce hyperkinesia in animal models (Lastres-Becker et al., 2003) | –CB2 agonists reduce inflammatory events and excitotoxicity in animal models (Palazuelos et al., 2009; Sagredo et al., 2009) |

| –CB1 agonists produce only modest effects in animal models (Lastres-Becker et al., 2003), whereas the data in patients are controversial (Müller-Vahl et al., 1999; Curtis and Rickards, 2006; Curtis et al., 2009) | –Cannabidiol and Δ9-THC reduce oxidative stress in animal models (Lastres-Becker et al., 2004; Sagredo et al., 2007) | |

| –CB1 agonists may also reduce excitotoxicity in animal models (Pintor et al., 2006; Blázquez et al., 2011), but they are lost during the progression of the disease | ||

| Parkinson's disease | –CB1 antagonists reduce bradykinesia in animal models (Fernández-Espejo et al., 2005; González et al., 2006; Kelsey et al., 2009) but not in patients (Mesnage et al., 2004) | –Antioxidant cannabinoids are neuroprotective in animal models (Lastres-Becker et al., 2005; García-Arencibia et al., 2007) |

| –CB1 agonists may reduce tremor in animal models (Sañudo-Peña and Walker, 1997) but the issue is not clear in patients (Consroe, 1998; Sieradzan et al., 2001; Carroll et al., 2004) | –CB2 agonists may reduce inflammatory events in animal models (Price et al., 2009; García et al., 2011) | |

| Tourette's syndrome | –Plant-derived cannabinoids and analogues reduce tics in patients (reviewed in Müller-Vahl, 2009) | |

| Dystonia | –Classic and non-classic cannabinoid agonists have antidystonic effects in animals models and patients (reviewed in Fernández-Ruiz and González, 2005) | |

| Dyskinesia | –CB1 agonists or antagonists attenuate levodopa-induced dyskinesia in animal models and patients (reviewed in Fabbrini et al., 2007) |

Δ9-THC, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol.

As mentioned above, the potential of cannabinoids as symptom-relieving agents in basal ganglia disorders is addressed here only marginally, and we will put the major emphasis on the potential of cannabinoids to control disease progression in PD and HD, given the important neuroprotective properties described for agonists of both CB1 and CB2 receptors (Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2005; 2010; and see also Table 1 for a summary of neuroprotective effects described for cannabinoid compounds in basal ganglia disorders). In this respect, it is important to remark that the molecular mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective properties of cannabinoids are quite diverse and include also some events not mediated by cannabinoid receptors, such as the blockade of NMDA receptors or the reduction of oxidative injury exerted by some specific groups of cannabinoids with particular chemical characteristics (Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2005; 2010;). Other neuroprotective actions of cannabinoids are definitively mediated by either CB1 (Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2005; 2010;) or CB2 receptors (Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2007; 2010;), and even through the activation of the endocannabinoid-related receptor TRPV1 (Veldhuis et al., 2003). These receptor-mediated events would be involved in the inhibition of glutamate release, reduction of calcium influx, improvement of blood supply to the injured brain and/or decrease of local inflammatory events exerted by cannabinoids (for review, see Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2005; 2007; 2010;). The present review will focus on these neuroprotective properties, particularly in two that have been demonstrated to be of major interest for basal ganglia disorders: their antioxidant properties and their activity at the CB2 receptors.

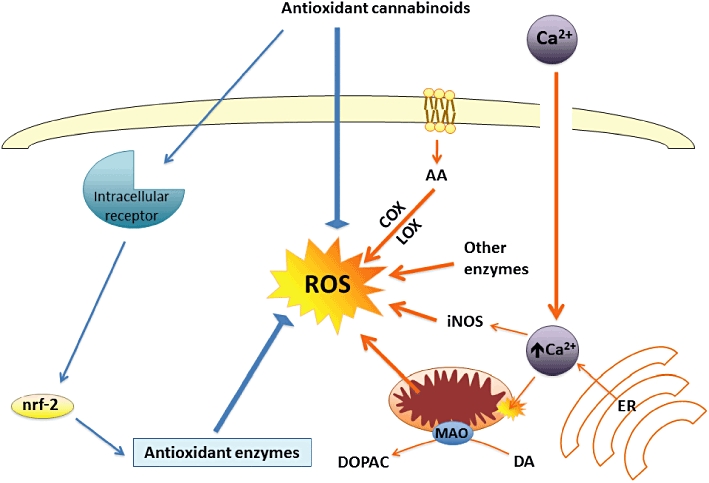

Antioxidant cannabinoids for the treatment of oxidative injury in basal ganglia disorders

The normal balance between oxidative events and antioxidant endogenous mechanisms is frequently disrupted [by an excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), by a deficiency in antioxidant endogenous mechanisms, or by both causes] in neurodegenerative disorders, including PD and HD (reviewed in Wang and Michaelis, 2010). Certain cannabinoids are able to restore this balance, thereby enhancing neuronal survival (Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2010, for review). A priori this capability seems to be inherent to compounds such as the plant-derived cannabinoids cannabidiol (CBD), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC) and cannabinol, or their analogues nabilone, levonantradol and dexanabinol, whose chemical structure with phenolic groups enables them to act as ROS scavengers (see Figure 3 and Marsicano et al., 2002, for details on those compounds that may serve for this function). This would be a cannabinoid receptor-independent effect (Eshhar et al., 1995; Hampson et al., 1998; Chen and Buck, 2000; Marsicano et al., 2002). However, additional mechanisms involving a direct improvement of endogenous antioxidant enzymes through the modulation of the signalling triggered by the transcription factor nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (nrf-2), as found for other classic antioxidants (see below), have been also proposed and are presently under investigation (reviewed in Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2010; see Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of representative cannabinoid compounds having cannabinoid receptor-independent antioxidant properties. The phenolic moiety responsible of this antioxidant effect is indicated with a green square. Δ9-THC, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol; Δ9-THCV, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin.

Figure 4.

Mechanisms proposed for the neuroprotective effects exerted by cannabinoids against oxidative injury that occurs in most neurodegenerative disorders, including HD and PD. These neuroprotective effects involve mainly CB1 and CB2 receptor-independent mechanisms. COX, cyclooxygenase; DA, dopamine; DOPAC, dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; LOX, lipoxygenase; MAO, monoamine oxidase; nrf-2, nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

The antioxidant potential of certain cannabinoids, particularly the case of CBD, a plant-derived cannabinoid with negligible activity at CB1 and CB2 receptors but significant antioxidant properties, has been already evaluated in experimental models of HD. Most of the studies have focused on the model of rats lesioned with 3-nitropropionic acid (reviewed in Pazos et al., 2008), a mitochondrial toxin that replicates the complex II deficiency characteristic of HD patients and that provokes striatal injury by mechanisms that mainly involve the Ca++-regulated protein calpain and generation of ROS (reviewed in Brouillet et al., 2005). Neuroprotective effects in this experimental model have been described for Δ9-THC (Lastres-Becker et al., 2004), CBD (Sagredo et al., 2007) or the Sativex®-like combination of botanical extracts of both phytocannabinoids (Sagredo et al., 2011). By contrast, selective CB1 receptor agonists, such as ACEA, or CB2 receptor agonists, such as HU-308, both devoid of antioxidant properties, failed to provide neuroprotection in this model (Sagredo et al., 2007). The effects of CBD (Sagredo et al., 2007) or the Sativex®-like combination of botanical extracts of Δ9-THC and CBD (Sagredo et al., 2011) in this HD model were not blocked by selective antagonists of either CB1 or CB2 receptors, thus supporting the idea that these effects are caused by the antioxidant and cannabinoid receptor-independent properties of these phytocannabinoids. These properties would be comparable, or even superior in some case, to those reported for other known antioxidant compounds, such as N-acetylcysteine, S-allylcysteine, coenzyme Q10, taurine, the flavonoid kaempferol, ascorbate, α-tocopherol, ginseng components, melatonin or dehydroepiandrosterone, all of which are highly effective at protecting the brain against 3-nitropropionate-induced neurotoxicity or in similar HD models (Fontaine et al., 2000; Nam et al., 2005; Tadros et al., 2005; Túnez et al., 2005; Herrera-Mundo et al., 2006; Lagoa et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009; Kalonia et al., 2010). It is possible, however, that this antioxidant/neuroprotective effect of phytocannabinoids involves the activation of signalling pathways implicated in the control of redox balance (e.g. nrf-2/antioxidant response element 7), as suggested recently for cystamine (Calkins et al., 2010). It is well-known that nrf-2 activation is neuroprotective against a variety of cytotoxic stimuli including 3-nitropropionate (Calkins et al., 2005), and indeed such activation may constitute a common mechanism of action for a range of different antioxidants, including phytocannabinoids. If this was the case, it could be that there was a cannabinoid receptor/target, other than CB1 or CB2 receptors, that might be coupled to the activation of nrf-2 signalling (see Figure 4). We are presently working in this direction.

Antioxidant cannabinoids have been also found highly effective as neuroprotective compounds in experimental models of PD and also by acting through cannabinoid receptor-independent mechanisms (reviewed in García-Arencibia et al., 2009b). This observation is particularly important in the case of PD due to two reasons: (i) PD is a degenerative disorder in which oxidative injury is particularly relevant (Wang and Michaelis, 2010); and (ii) the hypokinetic profile of most of the cannabinoids able to activate CB1 receptors represents a disadvantage for this disease because, in long-term treatments, agonists of this receptor can acutely enhance rather than reduce motor disability, as a few clinical data have already revealed (reviewed in Fernández-Ruiz and González, 2005; Fernández-Ruiz, 2009). Therefore, major efforts are in the direction to find cannabinoid molecules that may provide neuroprotection based on their antioxidant properties and that may also activate CB2 receptors (see below), but that do not activate CB1 receptors, or even, they are able to block them, which may provide additional benefits in the relief of specific symptoms as bradykinesia. An interesting case with this profile is the phytocannabinoid Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin (Δ9-THCV), which is presently under investigation in PD (see below). Most of the studies to determine the antioxidant properties of certain cannabinoids in PD have been conducted in rats with unilateral lesions of the nigrostriatal neurons caused by 6-hydroxydopamine (reviewed in García-Arencibia et al., 2009b). Neuroprotective effects in this experimental model have been described for Δ9-THC (Lastres-Becker et al., 2005), CBD (Lastres-Becker et al., 2005; García-Arencibia et al., 2007), the antioxidant anandamide analogue AM404 (García-Arencibia et al., 2007) and Δ9-THCV (García et al., 2011). Similar effects were found with the synthetic CB1/CB2 receptor agonist CP55,940 in an invertebrate model of PD (Jiménez-Del-Rio et al., 2008). A priori these compounds acted through antioxidant mechanisms that seem to be independent of CB1 or CB2 receptors, although selective activation of CB2 receptors showed efficacy in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-lesioned mice (Price et al., 2009; see below), but not in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats (García-Arencibia et al., 2007). In addition, CB1 receptor-deficient mice display an increased vulnerability to 6-hydroxydopamine lesions (Pérez-Rial et al., 2011). However, selective CB1 receptor agonists, such as ACEA, have been found not to protect against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced damage (García-Arencibia et al., 2007) and they may aggravate major Parkinsonian symptoms, given the hypokinetic effects associated with the activation of CB1 receptors (García-Arencibia et al., 2009b). Therefore, these data support the idea that antioxidant and cannabinoid receptor-independent cannabinoids may serve as potential neuroprotective agents against oxidative injury frequently observed in PD.

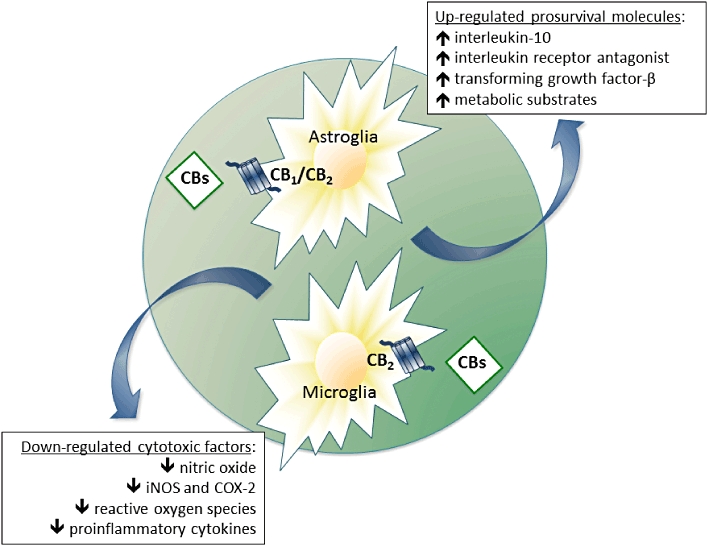

CB2 receptor agonists for the treatment of inflammatory events in basal ganglia disorders

The pathogenesis of PD, HD and other neurodegenerative disorders also includes the development of local inflammatory events that are caused by the recruitment and activation of astrocytes and microglial cells at the lesioned structures (Amor et al., 2010, for review). These responses, in particular in the case of microglial cells, although initially aimed at eliminating dead neurons and repairing the brain parenchyma, may become negative when they are permanently activated as happens in chronic neurodegenerative disorders, then aggravating neuronal damage (Heneka et al., 2010, for review). In the case of reactive microglial cells, this toxicity is due to the generation and release of different factors, such as nitric oxide, proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β) and ROS, all able to deteriorate neuronal homeostasis (Lull and Block, 2010, for review). Numerous studies have demonstrated that various cannabinoid agonists also have important anti-inflammatory properties exerted, for example, by reducing the generation of these cytotoxic factors (reviewed in Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2007; Stella, 2009), an effect preferentially mediated by the activation of CB2 receptors (see Figure 5). By contrast, cannabinoid agonists might also increase the production of prosurvival molecules, such as several trophic factors (e.g. transforming growth factor-β) or anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. interleukin-10, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist) (Smith et al., 2000; Molina-Holgado et al., 2003; Correa et al., 2010), or improve the trophic support exerted by astrocytes on neurons (Guzmán and Sánchez, 1999), an effect possibly mediated by the activation of CB1 receptors, although a role for CB2 receptors can not be excluded (Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2007; see Figure 5). Therefore, CB2 receptors appear to be the key target for these glial-mediated effects of cannabinoids, but the presence of this receptor type in the healthy brain is very weak and restricted to specific subpopulations of astrocytes, microglial cells and, to a lesser extent, neurons (reviewed in Benito et al., 2008). However, numerous studies developed from the pioneering study by Benito et al. (2003) using post-mortem brain samples from Alzheimer's disease patients, have provided solid evidence that CB2 receptors experience a marked up-regulation in glial elements in those structures undergoing neuronal damage in different pathological conditions, including HD and PD. Table 2 contains a summary of major characteristics of all in vivo studies showing up-regulation of CB2 receptors in different disorders or pathological conditions. Importantly, in most of these diseases, the activation of CB2 receptors has been associated with reduced proinflammatory events and enhanced neuronal survival, thereby supporting the importance of this receptor as a potential therapeutic target in neuroinflammatory/neurodegenerative conditions (reviewed in Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2007; 2010;). In addition, it should be remarked that CB2 agonists, in comparison with CB1 agonists, are devoid of undesirable CNS side effects, like sedation and psychotomimetic effects.

Figure 5.

Mechanisms proposed for the neuroprotective effects exerted by cannabinoids against inflammatory events that occur in most neurodegenerative disorders, including Huntington's disease and Parkinson's disease. These neuroprotective effects involve mainly the activation of CB2 receptors located in glial cells (reactive microglia and/or astrocytes). COX-2: cyclooxygenase type-2; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide.

Table 2.

Major characteristics of those studies showing CB2 receptor up-regulation in Huntington's disease, Parkinson's disease and other pathological conditions

| Insult/disease model | CB2-positive cells | Observed effect | Technique | Animal species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huntington's disease | |||||

| Malonate lesion | Astrocytes | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Rat | Sagredo et al., 2009 |

| Microglia | ↑ CB2 mRNA | qRT-PCR | |||

| Mutant huntingtin | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Mouse and human | Palazuelos et al., 2009 |

| ↑ CB2 mRNA | qRT-PCR | ||||

| Parkinson's disease | |||||

| MPTP lesion | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Mouse | Price et al., 2009 |

| LPS lesion | Microglia? | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Mouse | García et al., 2011 |

| Other pathological conditions | |||||

| Chronic constriction injury | Microglia | ↑ CB2 mRNA | ISH | Rat | Zhang et al., 2003 |

| Freund's complete adjuvant injection | |||||

| Spinal nerve ligation | |||||

| Spinal nerve ligation | Neurons | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Rat | Wotherspoon et al., 2005 |

| Spinal cord ligation | N.A. | ↑ CB2 | qRT-PCR | Mouse | Beltramo et al., 2006 |

| Peripheral nerve transection | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Rat | Romero-Sandoval et al., 2008 |

| Perivascular microglia | |||||

| Neuropathic pain | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Mouse | Luongo et al., 2009 |

| Astrocytes | |||||

| Paw incision | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Rat | Alkaitis et al., 2010 |

| Lipopolysaccharide | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | WB | Rat | Mukhopadhyay et al., 2006 |

| Multiple sclerosis | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Human | Benito et al., 2007 |

| Astrocytes | |||||

| Experimental autoimmune enchepalomyelitis | Microglia | ↑ CB2 mRNA | qRT-PCR | Mouse | Maresz et al., 2005 |

| EAE, multiple sclerosis | Myeloid progenitors | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Mouse and Human | Palazuelos et al., 2008 |

| Microglia | ↑ CB2 mRNA | qRT-PCR | |||

| Theiler's virus | N.A. | ↑ CB2 mRNA | qRT-PCR | Mouse | Loría et al., 2008 |

| Multiple sclerosis | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Human | Yiangou et al., 2006 |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | WB | ||||

| Hemicerebellectomy | Neurons | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Rat | Viscomi et al., 2009 |

| ↑ CB2 mRNA | qRT-PCR | ||||

| Middle cerebral artery occlusion | Macrophages/microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IF | Rat | Ashton et al., 2007 |

| Hypoxia-ischaemia | WB | ||||

| Middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion | N.A. | ↑ CB2 mRNA | qRT-PCR | Mouse | Zhang et al., 2008 |

| Alzheimer's disease | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Human | Benito et al., 2003 |

| Alzheimer's disease | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Human | Ramirez et al., 2005 |

| Alzheimer's disease | N.A. | ↑ CB2 mRNA | Gene-chip microarrays | Human | Grünblatt et al., 2007 |

| qRT-PCR | |||||

| β-Amyloid | N.A. | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Rat | Esposito et al., 2007 |

| ↑ CB2 mRNA | qRT-PCR | ||||

| Down's syndrome | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Human | Núñez et al., 2008 |

| Simian immunodeficiency virus | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Macaque | Benito et al., 2005 |

| MDMA neurotoxicity | Microglia | ↑ CB2 protein | IHC | Rat | Torres et al., 2010 |

EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; IF, immunofluorescence; IHC, immunohistochemistry; ISH, in situ hybridization; MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine; N.A., not analysed; WB, Western blotting.

The potential of CB2 receptor agonists has been also studied in basal ganglia disorders, particularly in HD, in which these agonists combined with antioxidant cannabinoids have been proposed as promising neuroprotective agents and might entry in clinical testing very soon (Fernández-Ruiz et al., 2010). An important aspect of HD pathology is that, as mentioned above, the brain of HD patients experiences a progressive decrease of CB1 receptors during the course of this disease that occurs in concert with the death of striatal projection neurons where CB1 receptors are located (reviewed in Pazos et al., 2008). This explains the lack of efficacy of CB1 agonists for the treatment of HD symptoms (e.g. chorea) in experimental models (Lastres-Becker et al., 2002b; 2003;) and the controversial data obtained in patients (Müller-Vahl et al., 1999; Curtis and Rickards, 2006; Curtis et al., 2009), as well as their poor activity as neuroprotective agents in models of HD generated by mitochondrial neurotoxins (Sagredo et al., 2007; 2009;). However, it should be noted that CB1 receptor activation afforded neuroprotection in other models, for example, in an excitotoxic model of HD (rats lesioned with quinolinate; Pintor et al., 2006), in a PC12 cell model expressing exon 1 mutant huntingtin (Scotter et al., 2010), and also in R6/2 mice, a transgenic model of HD (Blázquez et al., 2011). However, in the latter model, the activation of CB1 receptors was effective only when the treatment was initiated before the onset of symptoms and not later, in concordance with the idea that an early reduction of CB1 receptors caused by mutant huntingtin is involved in HD pathogenesis, as we have recently reported (Blázquez et al., 2011). We assume that an early pharmacological correction of this reduced CB1 receptor signalling may be positive in presymptomatic phases of HD, but it does not appear that CB1 receptor agonists work at later symptomatic phases (Blázquez et al., 2011; see also Dowie et al., 2009). This places CB2 receptors, and also antioxidant cannabinoid receptor-independent mechanisms described in the previous section, as the key targets within the cannabinoid system for a long-term cannabinoid-based neuroprotective treatment in HD. As mentioned above, the presence of this receptor type in the healthy striatum is relatively modest, but it is, however, markedly up-regulated in reactive microglial cells, and also in astrocytes, when striatal degeneration progresses, a process observed both in HD patients (Palazuelos et al., 2009) and in rats lesioned with malonate (Sagredo et al., 2009) or in R6/2 mice (Palazuelos et al., 2009). In this context, it is likely that compounds targeting selectively this receptor type may be effective in attenuating striatal degeneration in HD, a notion that has been demonstrated recently in various studies using different animal models in which inflammatory events associated with glial activation are predominant over other cytotoxic events that cooperatively contribute to HD pathogenesis in patients (Borrell-Pages et al., 2006). This is the case of striatal injury in rats generated by unilateral injections of malonate, another complex II inhibitor that, in contrast with 3-nitropropionic acid, produces cell death through the activation of apoptotic pathways and enhancement of proinflammatory factors (Sagredo et al., 2009). We found neuroprotection with selective CB2 receptor agonists in these rats, whereas selective CB1 receptor agonists or antioxidant cannabinoids like CBD were not effective (Sagredo et al., 2009). The effects of CB2 receptor agonists were antagonized by selective CB2 receptor antagonists, and CB2 receptor-deficient mice were more vulnerable to malonate lesions (Sagredo et al., 2009), thus stressing the importance of CB2 receptors in this model. We also demonstrated that the activation of this receptor type located in glial cells, particularly in reactive microglial cells within the striatal parenchyma, reduced the proinflammatory scenario caused by the malonate lesion, with a reduction in the generation of TNF-α and other proinflammatory factors (e.g. cyclooxygenase-2, inducible nitric oxide synthase) (Sagredo et al., 2009). Similar results have been recently found for CB2 receptor agonists in other models of HD such as R6/2 transgenic mice (Palazuelos et al., 2009) or mice lesioned with the excitotoxin quinolinate (Palazuelos et al., 2009), or for the Sativex®-like combination of botanical extracts of Δ9-THC (active at CB1 and CB2 receptors) and CBD in malonate-lesioned mice (Sagredo et al., 2011).

On the other hand, the question of CB2 receptors in PD has remained elusive for a long time. The difficulty in generating an appropriate antibody against this receptor that selectively labels CB2 receptor-containing cells, as well as the scarcity of alternative experimental tools, has delayed the identification of this receptor in lesioned structures, for example, substantia nigra and striatum, in Parkinsonian models. Price et al. (2009) were the first to demonstrate CB2-positive immunostaining in a classic model of PD in rodents, namely MPTP-lesioned mice, in which they identified the receptor in reactive microglial cells (Price et al., 2009). We also explored the issue in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats and mice, but our data did not reveal a significant up-regulatory response of these receptors in lesioned substantia nigra, showing poor response in rats (García et al., 2011) or equivalent immunostaining levels between lesioned and non-lesioned sides in mice (Garcia and Fernández-Ruiz, unpubl. results). This was concordant with the finding, mentioned in the previous section, that the neuroprotective effect of CB2 receptor agonists was very modest in this PD model (García-Arencibia et al., 2007), in which only antioxidant cannabinoids protected nigral neurons (Lastres-Becker et al., 2005; García-Arencibia et al., 2007), and also with the observation that the vulnerability to 6-hydroxydopamine was similar in CB2 receptor-deficient mice and wild-type animals (García et al., 2011). We assumed that this might be related to the poor inflammatory responses frequently found in models of PD generated with 6-hydroxydopamine and therefore went to a more proinflammatory model in which nigral lesions were caused by local application of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Mice-lesioned with LPS showed a profound up-regulation of CB2 receptors in the nigral parenchyma (García et al., 2011) and, in this case, the activation of CB2 receptors with the selective agonist HU-308 or with the phytocannabinoid Δ9-THCV preserved tyrosine hydroxylase-positive neurons in the LPS-lesioned substantia nigra, whereas CB2 receptor-deficient mice were more vulnerable to LPS than wild-type animals (García et al., 2011). Similar findings were obtained by Price et al. (2009) after the activation of CB2 receptors in MPTP-lesioned mice, and also in in vitro studies in which neuronal cells were incubated with conditioned media generated by exposing glial cells to the non-selective cannabinoid agonist HU-210, which showed high rates of survival compared with the poor effects found upon the direct exposure of neuronal cells to HU-210 (Lastres-Becker et al., 2005). All these data support the possibility that CB2 receptors may be a relevant cannabinoid target also in PD, serving to control local inflammatory events and, particularly, the generation of glial-derived cytotoxic factors that play a key role in PD pathogenesis (reviewed in Lee et al., 2009).

Concluding remarks and futures perspectives

Over the last decade, a considerable volume of preclinical work has allowed the accumulation of solid evidence to assume that the endocannabinoid system may serve as a target to develop potential neuroprotective agents for the treatment of basal ganglia diseases and also other neurodegenerative disorders. In this article, we have reviewed all this preclinical work and have discussed the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of cannabinoids, putting emphasis on two aspects: (i) their capability to decrease oxidative injury by acting as scavengers of ROS or by enhancing endogenous antioxidant defences, a property independent of CB1 and CB2 receptors and restricted to specific cannabinoids; and (ii) their anti-inflammatory activity, that is exerted predominantly through the activation of CB2 receptors located on glial elements, in which cannabinoids would enhance neuronal survival by inhibiting microglia-mediated cytotoxic influences and/or by increasing astroglia-mediated positive effects. However, as has been mentioned, most of the studies that have examined the therapeutic potential of cannabinoids in these disorders have been conducted in animal or cellular models, whereas the number of clinical trials is still very limited. Therefore, it should be expected that the number of studies examining this potential increases in next years, as soon as the promising expectations generated for these molecules progress from the present preclinical evidence to a true clinical application. In this respect, given the capability of cannabinoids to serve as neuroprotective agents against oxidative injury, inflammation and also other cytotoxic insults, as well as the current belief that these cytotoxic processes occur in a synergistic manner during the pathogenesis of HD and PD in humans, it would be important that the type of cannabinoid compound(s) that might be subjected to clinical evaluation in HD or PD would be a broad-spectrum, non-selective or hybrid compound, or alternatively a combination of compounds, which act on a range of targets known to mediate a neuroprotective effect.

Acknowledgments

The experimental work carried out by our group and that has been mentioned in this review article, has been supported during the last years by grants from Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red sobre Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CB06/05/0005, CB06/05/0089 and CB06/05/1109), Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (SAF2006-11333, SAF2007-61565, SAF2009-08403, SAF2009-11847 and SAF2010-16706), Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid (S-SAL-0261/2006) and GW Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Miguel Moreno-Martet and Carmen Rodríguez-Cueto are predoctoral students supported by the Ministry of Education (FPU programme) and MICINN (FPI programme), respectively. The authors are indebted to all colleagues who contributed in this experimental work and to Yolanda García-Movellán for administrative support.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CBD

cannabidiol

- CNS

central nervous system

- FAAH

fatty acid amide hydrolase

- HD

Huntington's disease

- Nrf-2

nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Δ9-THC

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol

- Δ9-THCV

Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have not any conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Teaching Materials; Figs 1–5 as PowerPoint slide.

References

- Alkaitis MS, Solorzano C, Landry RP, Piomelli D, DeLeo JA, Romero-Sandoval EA. Evidence for a role of endocannabinoids, astrocytes and p38 phosphorylation in the resolution of postoperative pain. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10891. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amor S, Puentes F, Baker D, van der Valk P. Inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology. 2010;129:154–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton JC, Rahman RM, Nair SM, Sutherland BA, Glass M, Appleton I. Cerebral hypoxia-ischemia and middle cerebral artery occlusion induce expression of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor in the brain. Neurosci Lett. 2007;412:114–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahr BA, Karanian DA, Makanji SS, Makriyannis A. Targeting the endocannabinoid system in treating brain disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15:351–365. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battista N, Bari M, Tarditi A, Mariotti C, Bachoud-Lévi AC, Zuccato C, et al. Severe deficiency of the fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) activity segregates with the Huntington's disease mutation in peripheral lymphocytes. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;27:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltramo M, Bernardini N, Bertorelli R, Campanella M, Nicolussi E, Fredduzzi S, et al. CB2 receptor-mediated antihyperalgesia: possible direct involvement of neural mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:1530–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito C, Nuñez E, Tolon RM, Carrier EJ, Rabano A, Hillard CJ, et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors and fatty acid amide hydrolase are selectively overexpressed in neuritic plaque-associated glia in Alzheimer's disease brains. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11136–11141. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-35-11136.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito C, Kim WK, Chavarría I, Hillard CJ, Mackie K, Tolón RM, et al. A glial endogenous cannabinoid system is upregulated in the brains of macaques with simian immunodeficiency virus-induced encephalitis. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2530–2536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3923-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito C, Romero JP, Tolon RM, Clemente D, Docagne F, Hillard CJ, et al. Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors and fatty acid amide hydrolase are specific markers of plaque cell subtypes in human multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2396–2402. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4814-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito C, Tolón RM, Pazos MR, Núñez E, Castillo AI, Romero J. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors in human brain inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:277–285. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez C, Chiarlone A, Sagredo O, Aguado T, Pazos MR, Resel E, et al. Loss of striatal type 1 cannabinoid receptors is a key pathogenic factor in Huntington's disease. Brain. 2011;134:119–136. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell-Pages M, Zala D, Humbert S, Saudou F. Huntington's disease: from huntingtin function and dysfunction to therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2642–2660. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillet E, Jacquard C, Bizat N, Blum D. 3-Nitropropionic acid: a mitochondrial toxin to uncover physiopathological mechanisms underlying striatal degeneration in Huntington's disease. J Neurochem. 2005;95:1521–1540. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins MJ, Jakel RJ, Johnson DA, Chan K, Kan YW, Johnson JA. Protection from mitochondrial complex II inhibition in vitro and in vivo by Nrf2-mediated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:244–249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408487101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins MJ, Townsend JA, Johnson DA, Johnson JA. Cystamine protects from 3-nitropropionic acid lesioning via induction of nf-e2 related factor 2 mediated transcription. Exp Neurol. 2010;224:307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll CB, Bain PG, Teare L, Liu X, Joint C, Wroath C, et al. Cannabis for dyskinesia in Parkinson disease: a randomized double-blind crossover study. Neurology. 2004;63:1245–1250. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000140288.48796.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Buck J. Cannabinoids protect cells from oxidative cell death: a receptor-independent mechanism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:807–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Takahashi KA, Castillo PE. Endocannabinoid-mediated synaptic plasticity in the CNS. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:37–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.112834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consroe P. Brain cannabinoid systems as targets for the therapy of neurological disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5:534–551. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa F, Hernangómez M, Mestre L, Loría F, Spagnolo A, Docagne F, et al. Anandamide enhances IL-10 production in activated microglia by targeting CB2 receptors: roles of ERK1/2, JNK, and NF-kappaB. Glia. 2010;58:135–147. doi: 10.1002/glia.20907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis A, Rickards H. Nabilone could treat chorea and irritability in Huntington's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;18:553–554. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2006.18.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis A, Mitchell I, Patel S, Ives N, Rickards H. A pilot study using nabilone for symptomatic treatment in Huntington's disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:2254–2259. doi: 10.1002/mds.22809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denovan-Wright EM, Robertson HA. Cannabinoid receptor messenger RNA levels decrease in subset neurons of the lateral striatum, cortex and hippocampus of transgenic Huntington's disease mice. Neuroscience. 2000;98:705–713. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V. Targeting the endocannabinoid system: to enhance or reduce? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:438–455. doi: 10.1038/nrd2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V. The endocannabinoid system: its general strategy of action, tools for its pharmacological manipulation and potential therapeutic exploitation. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowie MJ, Bradshaw HB, Howard ML, Nicholson LF, Faull RL, Hannan AJ, et al. Altered CB1 receptor and endocannabinoid levels precede motor symptom onset in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease. Neuroscience. 2009;163:456–465. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshhar N, Striem S, Kohen R, Tirosh O, Biegon A. Neuroprotective and antioxidant activities of HU-211, a novel NMDA receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;283:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00271-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G, Scuderi C, Savani C, Steardo L, Jr, De Filippis D, Cottone P, et al. Cannabidiol in vivo blunts beta-amyloid induced neuroinflammation by suppressing IL-1beta and iNOS expression. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:1272–1279. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbrini G, Brotchie JM, Grandas F, Nomoto M, Goetz CG. Levodopa-induced dyskinesias. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1379–1389. doi: 10.1002/mds.21475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Espejo E, Caraballo I, Rodríguez de Fonseca F, El Banoua F, Ferrer B, Flores JA, et al. Cannabinoid CB1 antagonists possess antiparkinsonian efficacy only in rats with very severe nigral lesion in experimental parkinsonism. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;18:591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ruiz J. The endocannabinoid system as a target for the treatment of motor dysfunction. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:1029–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ruiz J, González S. Cannabinoid control of motor function at the basal ganglia. In: Pertwee RG, editor. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology – 168 – Cannabinoids. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2005. pp. 479–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ruiz J, González S, Romero J, Ramos JA. Cannabinoids in neurodegeneration and neuroprotection. In: Mechoulam R, editor. Cannabinoids As Therapeutics (MDT. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhaüser Verlag; 2005. pp. 79–109. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ruiz J, Romero J, Velasco G, Tolón RM, Ramos JA, Guzmán M. Cannabinoid CB2 receptor: a new target for controlling neural cell survival? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ruiz J, García C, Sagredo O, Gómez-Ruiz M, de Lago E. The endocannabinoid system as a target for the treatment of neuronal damage. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:387–404. doi: 10.1517/14728221003709792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I, Martinez A, Blanco R, Dalfó E, Carmona M. Neuropathology of sporadic Parkinson's disease before the appearance of parkinsonism: preclinical Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0482-8. (in press). doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine MA, Geddes JW, Banks A, Butterfield DA. Effect of exogenous and endogenous antioxidants on 3-nitropionic acid-induced in vivo oxidative stress and striatal lesions: insights into Huntington's disease. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1709–1715. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García C, Palomo C, García-Arencibia M, Ramos JA, Pertwee RG, Fernández-Ruiz J. Symptom-relieving and neuroprotective effects of the phytocannabinoid Δ9-THCV in animal models of Parkinson's disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1495–1506. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Arencibia M, González S, de Lago E, Ramos JA, Mechoulam R, Fernández-Ruiz J. Evaluation of the neuroprotective effect of cannabinoids in a rat model of Parkinson's disease: importance of antioxidant and cannabinoid receptor-independent properties. Brain Res. 2007;1134:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Arencibia M, García C, Kurz A, Rodríguez-Navarro JA, Gispert-Sáchez S, Mena MA, et al. Cannabinoid CB1 receptors are early downregulated followed by a further upregulation in the basal ganglia of mice with deletion of specific park genes. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2009a;73:269–275. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-92660-4_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Arencibia M, García C, Fernández-Ruiz J. Cannabinoids and Parkinson's disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009b;8:432–439. doi: 10.2174/187152709789824642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdeman GL, Fernández-Ruiz J. The endocannabinoid system in the physiology and pathophysiology of the basal ganglia. In: Kofalvi A, editor. Cannabinoids and the Brain. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2008. pp. 423–483. [Google Scholar]

- Glass M, Dragunow M, Faull RLM. The pattern of neurodegeneration in Huntington's disease: a comparative study of cannabinoid, dopamine, adenosine and GABA-A receptor alterations in the human basal ganglia in Huntington's disease. Neuroscience. 2000;97:505–519. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González S, Scorticati C, García-Arencibia M, de Miguel R, Ramos JA, Fernández-Ruiz J. Effects of rimonabant, a selective cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist, in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Brain Res. 2006;1073-1074:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünblatt E, Zander N, Bartl J, Jie L, Monoranu CM, Arzberger T, et al. Comparison analysis of gene expression patterns between sporadic Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;12:291–311. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-12402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán M, Sánchez C. Effects of cannabinoids on energy metabolism. Life Sci. 1999;65:657–664. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson AJ, Grimaldi M, Axelrod J, Wink D. Cannabidiol and (-)Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol are neuroprotective antioxidants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8268–8273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Rodríguez JJ, Verkhratsky A. Neuroglia in neurodegeneration. Brain Res Rev. 2010;63:189–211. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Mundo MN, Silva-Adaya D, Maldonado PD, Galvan-Arzate S, Andres-Martinez L, Perez-De La Cruz V, et al. S-Allylcysteine prevents the rat from 3-nitropropionic acid-induced hyperactivity, early markers of oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Neurosci Res. 2006;56:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley MJ, Mash DC, Jenner P. Expression of cannabinoid CB1 receptor mRNA in basal ganglia of normal and parkinsonian human brain. J Neural Transm. 2003;110:1279–1288. doi: 10.1007/s00702-003-0033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janero DR, Makriyannis A. Cannabinoid receptor antagonists: pharmacological opportunities, clinical experience, and translational prognosis. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2009;14:43–65. doi: 10.1517/14728210902736568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Del-Rio M, Daza-Restrepo A, Velez-Pardo C. The cannabinoid CP55,940 prolongs survival and improves locomotor activity in Drosophila melanogaster against paraquat: implications in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Res. 2008;61:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalonia H, Kumar P, Kumar A. Targeting oxidative stress attenuates malonic acid induced Huntington like behavioral and mitochondrial alterations in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;634:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano M, Ohno-Shosaku T, Hashimotodani Y, Uchigashima M, Watanabe M. Endocannabinoid-mediated control of synaptic transmission. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:309–380. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey JE, Harris O, Cassin J. The CB1 antagonist rimonabant is adjunctively therapeutic as well as monotherapeutic in an animal model of Parkinson's disease. Behav Brain Res. 2009;203:304–307. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagoa R, López-Sánchez C, Samhan-Arias AK, Gañan CM, Garcia-Martinez V, Gutierrez-Merino C. Kaempferol protects against rat striatal degeneration induced by 3-nitropropionic acid. J Neurochem. 2009;111:473–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanciego JL, Barroso-Chinea P, Rico AJ, Conte-Perales L, Callén L, Roda E, et al. Expression of the mRNA coding the cannabinoid receptor 2 in the pallidal complex of Macaca fascicularis. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:97–104. doi: 10.1177/0269881110367732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastres-Becker I, Berrendero F, Lucas JJ, Martin E, Yamamoto A, Ramos JA, et al. Loss of mRNA levels, binding and activation of GTP-binding proteins for cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the basal ganglia of a transgenic model of Huntington's disease. Brain Res. 2002a;929:236–242. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastres-Becker I, Hansen HH, Berrendero F, de Miguel R, Pérez-Rosado A, Manzanares J, et al. Loss of cannabinoid CB1 receptors and alleviation of motor hyperactivity and neurochemical deficits by endocannabinoid uptake inhibition in a rat model of Huntington's disease. Synapse. 2002b;44:23–35. doi: 10.1002/syn.10054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastres-Becker I, de Miguel R, De Petrocellis L, Makriyannis A, Di Marzo V, Fernández-Ruiz J. Compounds acting at the endocannabinoid and/or endovanilloid systems reduce hyperkinesia in a rat model of Huntington's disease. J Neurochem. 2003;84:1097–1109. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastres-Becker I, Bizat N, Boyer F, Hantraye P, Fernández-Ruiz JJ, Brouillet E. Potential involvement of cannabinoid receptors in 3-nitropropionic acid toxicity in vivo: implication for Huntington's disease. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2375–2379. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200410250-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastres-Becker I, Molina-Holgado F, Ramos JA, Mechoulam R, Fernández-Ruiz J. Cannabinoids provide neuroprotection against 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity in vivo and in vitro: relevance to Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Tran T, Tansey MG. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson's disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009;4:419–429. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9176-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loría F, Petrosino S, Mestre L, Spagnolo A, Correa F, Hernangómez M, et al. Study of the regulation of the endocannabinoid system in a virus model of multiple sclerosis reveals a therapeutic effect of palmitoylethanolamide. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:633–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lull ME, Block ML. Microglial activation and chronic neurodegeneration. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luongo L, Palazzo E, Tambaro S, Giordano C, Gatta L, Scafuro MA, et al. 1-(2′,4′-dichlorophenyl)-6-methyl-N-cyclohexylamine-1,4-dihydroindeno[1,2-c]pyrazole-3-carboxamide, a novel CB2 agonist, alleviates neuropathic pain through functional microglial changes in mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;37:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccarrone M, Battista N, Centonze D. The endocannabinoid pathway in Huntington's disease: a comparison with other neurodegenerative diseases. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;81:349–379. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maresz K, Carrier EJ, Ponomarev ED, Hillard CJ, Dittel BN. Modulation of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor in microglial cells in response to inflammatory stimuli. J Neurochem. 2005;95:437–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsicano G, Lutz B. Neuromodulatory functions of the endocannabinoid system. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006;29:27–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsicano G, Moosmann B, Hermann H, Lutz B, Behl C. Neuroprotective properties of cannabinoids against oxidative stress: role of the cannabinoid receptor CB1. J Neurochem. 2002;80:448–456. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Orgado J, Fernández-Ruiz J, Romero J. The endocannabinoid system in neuropathological states. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21:172–180. doi: 10.1080/09540260902782828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesnage V, Houeto JL, Bonnet AM, Clavier I, Arnulf I, Cattelin F, et al. Neurokinin B, neurotensin, and cannabinoid receptor antagonists and Parkinson disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27:108–110. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Holgado F, Pinteaux E, Moore JD, Molina-Holgado E, Guaza C, Gibson RM, et al. Endogenous interleukin-1 receptor antagonist mediates anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions of cannabinoids in neurons and glia. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6470–6474. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06470.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay S, Das S, Williams EA, Moore D, Jones JD, Zahm DS, et al. Lipopolysaccharide and cyclic AMP regulation of CB2 cannabinoid receptor levels in rat brain and mouse RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;181:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Vahl KR. Tourette's syndrome. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2009;1:397–410. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-88955-7_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-Vahl KR, Schneider U, Emrich HM. Nabilone increases choreatic movements in Huntington's disease. Mov Disord. 1999;14:1038–1040. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199911)14:6<1038::aid-mds1024>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatsu T, Sawada M. Biochemistry of postmortem brains in Parkinson's disease: historical overview and future prospects. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2007;72:113–120. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-73574-9_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam E, Lee SM, Koh SE, Joo WS, Maeng S, Im HI, et al. Melatonin protects against neuronal damage induced by 3-nitropropionic acid in rat striatum. Brain Res. 2005;1046:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núñez E, Benito C, Tolón RM, Hillard CJ, Griffin WS, Romero J. Glial expression of cannabinoid CB2 receptors and fatty acid amide hydrolase are beta amyloid-linked events in Down's syndrome. Neuroscience. 2008;151:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazuelos J, Davoust N, Julien B, Hatterer E, Aguado T, Mechoulam R, et al. The CB2 cannabinoid receptor controls myeloid progenitor trafficking: involvement in the pathogenesis of an animal model of multiple sclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13320–13329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazuelos J, Aguado T, Pazos MR, Julien B, Carrasco C, Resel E, et al. Microglial CB2 cannabinoid receptors are neuroprotective in Huntington's disease excitotoxicity. Brain. 2009;132:3152–3164. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazos MR, Sagredo O, Fernández-Ruiz J. The endocannabinoid system in Huntington's disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:2317–2325. doi: 10.2174/138161208785740108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Rial S, García-Gutiérrez MS, Molina JA, Pérez-Nievas BG, Ledent C, Leiva C, et al. Increased vulnerability to 6-hydroxydopamine lesion and reduced development of dyskinesias in mice lacking CB1 cannabinoid receptors. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:631–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Emerging strategies for exploiting cannabinoid receptor agonists as medicines. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:397–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG, Howlett AC, Abood ME, Alexander SP, Di Marzo V, Elphick MR, et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB1 and CB2. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:588–631. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintor A, Tebano MT, Martire A, Grieco R, Galluzzo M, Scattoni ML, et al. The cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 attenuates the effects induced by quinolinic acid in the rat striatum. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51:1004–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DA, Martinez AA, Seillier A, Koek W, Acosta Y, Fernández E, et al. WIN55,212-2, a cannabinoid receptor agonist, protects against nigrostriatal cell loss in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:2177–2186. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez BG, Blazquez C, Gomez del Pulgar T, Guzman M, de Ceballos ML. Prevention of Alzheimer's disease pathology by cannabinoids: neuroprotection mediated by blockade of microglial activation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1904–1913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4540-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Sandoval A, Nutile-McMenemy N, DeLeo JA. Spinal microglial and perivascular cell cannabinoid receptor type 2 activation reduces behavioral hypersensitivity without tolerance after peripheral nerve injury. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:722–734. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318167af74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roze E, Bonnet C, Betuing S, Caboche J. Huntington's disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;685:45–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagredo O, Ramos JA, Decio A, Mechoulam R, Fernández-Ruiz J. Cannabidiol reduced the striatal atrophy caused 3-nitropropionic acid in vivo by mechanisms independent of the activation of cannabinoid, vanilloid TRPV1 and adenosine A2A receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:843–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagredo O, González S, Aroyo I, Pazos MR, Benito C, Lastres-Becker I, et al. Cannabinoid CB2 receptor agonists protect the striatum against malonate toxicity: relevance for Huntington's disease. Glia. 2009;57:1154–1167. doi: 10.1002/glia.20838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagredo O, Pazos MR, Satta V, Ramos JA, Pertwee RG, Fernández-Ruiz J. Neuroprotective effects of phytocannabinoid-based medicines in experimental models of Huntington's disease. J. Neurosci Res. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jnr.22682. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sañudo-Peña MC, Walker JM. Role of the subthalamic nucleus in cannabinoid actions in the substantia nigra of the rat. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1635–1638. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotter EL, Goodfellow CE, Graham ES, Dragunow M, Glass M. Neuroprotective potential of CB1 receptor agonists in an in vitro model of Huntington's disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:747–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00773.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieradzan KA, Fox SH, Hill M, Dick JP, Crossman AR, Brotchie JM. Cannabinoids reduce levodopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease: a pilot study. Neurology. 2001;57:2108–2111. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.11.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, Terminelli C, Denhardt G. Effects of cannabinoid receptor agonist and antagonist ligands on production of inflammatory cytokines and anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 in endotoxemic mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:136–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella N. Endocannabinoid signaling in microglial cells. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros MG, Khalifa AE, Abdel-Naim AB, Arafa HM. Neuroprotective effect of taurine in 3-nitropropionic acid-induced experimental animal model of Huntington's disease phenotype. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B, Beal MF. Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:R183–R194. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres E, Gutierrez-Lopez MD, Borcel E, Peraile I, Mayado A, O'Shea E, et al. Evidence that MDMA (‘ecstasy’) increases cannabinoid CB2 receptor expression in microglial cells: role in the neuroinflammatory response in rat brain. J Neurochem. 2010;113:67–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Túnez I, Muñoz MC, Montilla P. Treatment with dehydroepiandrosterone prevents oxidative stress induced by 3-nitropropionic acid in synaptosomes. Pharmacology. 2005;74:113–118. doi: 10.1159/000084169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Laere K, Casteels C, Dhollander I, Goffin K, Grachev I, Bormans G, et al. Widespread decrease of type 1 cannabinoid receptor availability in Huntington disease in vivo. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1413–1417. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.077156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis WB, van der Stelt M, Wadman MW, van Zadelhoff G, Maccarrone M, Fezza F, et al. Neuroprotection by the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide and arvanil against in vivo excitotoxicity in the rat: role of vanilloid receptors and lipoxygenases. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4127–4133. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04127.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viscomi MT, Oddi S, Latini L, Pasquariello N, Florenzano F, Bernardi G, et al. Selective CB2 receptor agonism protects central neurons from remote axotomy-induced apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt pathway. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4564–4570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0786-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh S, Mnich K, Mackie K, Gorman AM, Finn DP, Dowd E. Loss of cannabinoid CB1 receptor expression in the 6-hydroxydopamine-induced nigrostriatal terminal lesion model of Parkinson's disease in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 2010;81:543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Michaelis EK. Selective neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress in the brain. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:12. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wotherspoon G, Fox A, McIntyre P, Colley S, Bevan S, Winter J. Peripheral nerve injury induces cannabinoid receptor 2 protein expression in rat sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 2005;135:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. Cannabinoid-based medicines for neurological disorders – clinical evidence. Mol Neurobiol. 2007;36:129–136. doi: 10.1007/s12035-007-0003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Calingasan NY, Wille EJ, Cormier K, Smith K, Ferrante RJ, et al. Combination therapy with coenzyme Q10 and creatine produces additive neuroprotective effects in models of Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1427–1439. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yiangou Y, Facer P, Durrenberger P, Chessell IP, Naylor A, Bountra C, et al. COX-2, CB2 and P2X7-immunoreactivities are increased in activated microglial cells/macrophages of multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord. BMC Neurol. 2006;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Hoffert C, Vu HK, Groblewski T, Ahmad S, O'Donnell D. Induction of CB2 receptor expression in the rat spinal cord of neuropathic but not inflammatory chronic pain models. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2750–2754. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Martin BR, Adler MW, Razdan RK, Ganea D, Tuma RF. Modulation of the balance between cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptor activation during cerebral ischemic/reperfusion injury. Neuroscience. 2008;152:753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato C, Valenza M, Cattaneo E. Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutical targets in Huntington's disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:905–981. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.