Abstract

Objective

To assess the frequency of elective induction of labour and its determinants in selected Latin America countries; quantify success in attaining vaginal delivery, and compare rates of caesarean and adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes after elective induction versus spontaneous labour in low-risk pregnancies.

Methods

Of 37 444 deliveries in women with low-risk pregnancies, 1847 (4.9%) were electively induced. The factors associated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes among cases of spontaneous and induced onset of labour were compared. Odds ratios for factors potentially associated with adverse outcomes were calculated, as were the relative risks of having an adverse maternal or perinatal outcome (both with their 95% confidence intervals). Adjustment using multiple logistic regression models followed these analyses.

Findings

Of 11 077 cases of induced labour, 1847 (16.7%) were elective. Elective inductions occurred in 4.9% of women with low-risk pregnancies (37 444). Oxytocin was the most common method used (83% of cases), either alone or combined with another. Of induced deliveries, 88.2% were vaginal. The most common maternal adverse events were: (i) a higher postpartum need for uterotonic drugs, (ii) a nearly threefold risk of admission to the intensive care unit; (iii) a fivefold risk of postpartum hysterectomy, and (iv) an increased need for anaesthesia/analgesia. Perinatal outcomes were satisfactory except for a 22% higher risk of delayed breastfeeding (i.e. initiation between 1 hour and 7 days postpartum).

Conclusion

Caution is mandatory when indicating elective labour induction because the increased risk of maternal and perinatal adverse outcomes is not outweighed by clear benefits.

ملخص

الغرض قياس تكرار التحريض الاختياري للولادة ومحدداته في بلدان منتقاة في أمريكا اللاتينية؛ وتحديد مقدار النجاح في تحقيق الولادة المهبلية، ومقارنة معدلات الجراحات القيصرية، والنتائج الضائرة للأمهات والفترة المحيطة بالولادة بعد إجراء التحريض الاختياري للولادة مقارنة بالولادة التلقائية في الحمل ذي الاختطار المنخفض.

الطريقة من بين 37444 ولادة لنساء لديهن حمل منخفض الاختطار، أجري تحريض اختياري للولادة في 1847 ولادة (بنسبة 4.9%). وأجريت مقارنة بين العوامل المرتبطة بالنتائج الضائرة للأمهات والفترة المحيطة بالولادة بين الولادات التلقائية والولادات التي جرى التحريض على بدئها. وحسبت نسب الأرجحية للعوامل المتوقعة المرتبطة بالنتائج الضائرة، سواء للاختطارات النسبية لحدوث نتائج ضائرة للأمهات والفترة المحيطة بالولادة (كل منهما بفاصلة ثقة 95%). ثم تلي تلك التحليلات تعديل باستخدام نماذج التحوّف اللوجستي المتعددة.

النتائج من بين 11077 ولادة جرى التحريض عليها، كان ذلك اختيارياً في 1847 ولادة (بنسبة 16.7%). جرى التحريض في 4.9% من النساء اللاتي لديهن حمل منخفض الاختطار (والذي كان عددهن 37444). وكان الأوكسيتوسين هو أكثر الطرق الشائعة استخداماً (بنسبة 83% من الحالات)، سواء كان منفرداً أو ضمن إجراءات أخرى. ومن بين الولادات التي جرى التحريض عليها حدث 88.2% ولادة مهبلية. وكانت أكثر الأحداث الضائرة شيوعاً هي: 1) زيادة الحاجة للأدوية المقوية لتوتر الرحم بعد الولادة؛ 2) زيادة خطر الإدخال إلى وحدة الرعاية المكثفة بمقدار ثلاثة أضعاف؛ 3) زيادة استئصال الرحم بعد الولادة بمقدار خمسة أضعاف؛ 4) زيادة الحاجة إلى التخدير والمسكنات. كانت النتائج في الفترة المحيطة بالولادة مرضية ماعدا زيادة قدرها 22% في خطر التأخر في الإرضاع من الثدي (أي تأخر بدء الإرضاع من الثدي بين ساعة و سبعة أيام بعد الولادة).

الاستنتاج يجب الالتزام بالحذر في قرار إجراء التحريض الاختياري للولادة نظراً لزيادة اختطار حدوث نتائج ضائرة في الفترة المحيطة بالولادة وهذه الأحداث تفوق المزايا المحتملة للتحريض الاختياري للولادة.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer la fréquence du déclenchement du travail sans indication médicale et ses déterminants dans une sélection de pays d’Amérique latine, quantifier la réussite d’un accouchement par voie vaginale et comparer les taux de césariennes et d’issues périnatales et maternelles négatives après le déclenchement du travail sans indication médicale par rapport au travail spontané, dans des grossesses à faible risque.

Méthodes

Sur 37 444 accouchements de femmes présentant des grossesses à faible risque, 1 847 (4,9%) ont été déclenchés sans indication médicale. On a comparé les facteurs associés aux issues périnatales et maternelles négatives dans des cas de début de travail spontané et déclenché. On a calculé les rapports des cotes des facteurs potentiellement associés aux issues négatives, ainsi que les risques relatifs d’issue périnatale ou maternelle négative (tous deux avec un intervalle de confiance de 95%). Suite à ces analyses, un ajustement a été effectué à l’aide de plusieurs modèles de régression logistique.

Résultats

Sur 11 077 cas de travail déclenché, 1 847 (16,7%) l'ont été sans indication médicale. Un déclenchement du travail sans indication médicale a été effectué chez 4,9% des femmes présentant des grossesses à faible risque (37 444). L’ocytocine était la méthode la plus communément utilisée (83% des cas), soit administrée seule, soit combinée avec une autre méthode. Pour les accouchements sans indication médicale, 88,2% ont eu lieu par voie vaginale. Les événements maternels négatifs les plus communs étaient: (i) un besoin supérieur de médicaments utérotoniques postpartum, (ii) un risque presque multiplié par 3 d’admission en unité de soins intensifs; (iii) un risque multiplié par 5 d’hystérectomie postpartum et (iv) une augmentation du besoin d'anesthésie/analgésie. Les issues périnatales étaient satisfaisantes, à l’exception d’une augmentation de 22% du risque d’allaitement retardé (c’est-à-dire une initiation entre 1 heure et 7 jours après l’accouchement).

Conclusion

Il est indispensable de faire preuve de prudence lors de la préconisation d’un accouchement sans indication médicale, car l’augmentation du risque d’issues périnatales et maternelles négatives n’est pas compensée par des avantages clairs.

Resumen

Objetivo

Evaluar la frecuencia de los partos inducidos electivos y sus factores determinantes en determinados países de Latinoamérica; cuantificar el éxito en la consecución de partos vaginales y comparar los porcentajes de cesáreas y de resultados maternos y perinatales adversos tras un parto inducido electivo con respecto a un parto espontáneo en embarazos de bajo riesgo.

Métodos

De 37 444 partos de mujeres con embarazos de bajo riesgo, 1847 (4,9%) fueron partos inducidos electivos. Se compararon los factores asociados a resultados maternos y perinatales adversos en los casos de inicio del parto espontáneo e inducido. Se calcularon los cocientes de posibilidades para los factores posiblemente asociados a resultados adversos, así como los riesgos relacionados con un resultado materno o perinatal adverso (ambos con un intervalo de confianza del 95%). Después de llevar a cabo estos análisis, se realizó un ajuste empleando modelos de regresión logística múltiple.

Resultados

De los 11 077 casos de parto inducido, 1847 (16,7%) fueron electivos. Las inducciones electivas se produjeron en un 4,9% de mujeres con embarazos de bajo riesgo (37 444). El método más utilizado fue la oxitocina (83% de los casos), como fármaco único o en combinación con otros medicamentos. Un 88,2% de los partos inducidos fueron vaginales. Los acontecimientos maternos adversos más comunes fueron: (i) una mayor necesidad de medicamentos uterotónicos tras el parto, (ii) un riesgo casi tres veces mayor de ingreso en la unidad de cuidados intensivos; (iii) un riesgo cinco veces mayor de histerectomía posparto y (iv) una mayor necesidad de anestésicos/analgésicos. Los resultados perinatales fueron satisfactorios excepto por un riesgo un 22% mayor de lactancia materna retardada (es decir, el inicio de la misma entre 1 hora y 7 días después del parto).

Conclusión

La precaución es obligatoria a la hora de recomendar una inducción electiva del parto, ya que el aumento del riesgo de resultados adversos maternos y perinatales no se ve compensado por unos beneficios claros.

Резюме

Цель

Оценить частоту элективной индукции родов и ее детерминанты в некоторых странах Латинской Америки; дать количественную оценку успехов в проведении вагинальных родов и сравнить показатели родов, проведенных методом кесарева сечения, и отрицательных материнских и перинатальных исходов после элективной индукции и после самопроизвольных родов при беременностях с низким риском осложнений.

Методы

Из 37 444 родов у беременных женщин с низким риском осложнений, 1847 (4,9%) были элективно индуцированными. Производилось сравнение факторов, связанных с отрицательными материнскими и перинатальными исходами, между случаями самопроизвольных и индуцированных родов. Проводился расчет отношения рисков для факторов, потенциально связанных с отрицательными исходами, таких как относительный риск отрицательного материнского или перинатального исхода (в обоих случаях – с 95% доверительным интервалом). Этот анализ завершался корректировкой с использованием моделей множественной логистической регрессии.

Результаты

Из 11 077 случаев индуцированных родов, 1847 (16,7%) были элективными. Элективная индукция наблюдалась у 4.9% беременных женщин с низким риском осложнений (37 444). Наиболее распространенным из использованных методов был окситоцин (83% случаев), один или в сочетании с другим методом. Из числа индуцированных родов, 88,2% были вагинальными. Наиболее распространенными отрицательными материнскими событиями были: (i) повышенная потребность в получении после родов лекарственных средств для сокращения матки, (ii) увеличение почти в три раза риска перевода в отделение интенсивной терапии; (iii) повышение почти в пять раз риска послеродовой гистерэктомии, и (iv) повышенная потребность в анестезии/аналгезии. Перинатальные исходы были удовлетворительными, за исключением повышения на 22% риска задержки начала кормления грудью (например, на период от одного часа до семи дней после родов).

Вывод

Необходимо проявлять сдержанность при показаниях к элективной индукции родов, так как повышенный риск материнских и перинатальных отрицательных исходов не компенсируется безусловной пользой.

摘要

目的

旨在评估选定的拉丁美洲国家选择性引产频率及其决定因素;量化阴道分娩的成功率并比较低风险妊娠中选择性引产和顺产之后剖腹产比率以及不良母体和围产结局。

方法

在低风险妊娠妇女的37 444例分娩中,1847(4.9%)是选择性引产。对顺产和引产案例中与不良母体和围产结局相关的因素进行比较。计算了与不良结局潜在相关的因素的相对危险度,同样计算了发生不良母体或围产结局的相对风险(95%可信区间)。该分析之后运用多元逻辑回归模型进行调整。

结果

11 077例引产中,1847例(16.7%)是选择性的。低风险妊娠妇女中(37 444),选择性引产发生率为4.9%。催产素是最常用的方法(83%),无论是单独使用还是与其他方法联合使用。在引产分娩中,88.2%是阴道分娩。最常见的母体不良反应是:(i) 产后较高的子宫收缩药物需求;(ii)近三倍的住进加护病房的风险;(iii)五倍的产后子宫切除风险;(iv)增加的麻醉/止痛需求。除了22%有较高的推迟母乳喂养(即产后1小时到7天)风险之外,围产结局还算令人满意。

结论

当孕产妇表示要进行选择性引产时,医生应予以强制性警告,因为孕产妇和围产期不良结局的风险增加,远远超过明显的好处。

Introduction

Elective labour induction without any medical or obstetric indication has been increasing in recent years. In some countries, 10% of all deliveries are electively induced.1–4 This increase has been attributed to greater demand by mothers and to logistic factors such as distance from the maternal dwelling to the hospital or a history of precipitate delivery.4–6 In addition, elective induction to suit the obstetrician’s schedule has been a contributing factor since the first half of the 20th century.7

In places where caesarean section rates are high, inducing labour in situations in which termination of pregnancy is advisable may help to reduce these rates.8,9 Nevertheless, the same is not necessarily true when labour is induced without any medical indication. Elective induction may in fact alter normal physiology when delivery begins and increase the rate of caesarean section, irrespective of parity, especially among women with an unfavourable cervix (e.g. women with the cervix in a posterior position, firm, poorly effaced and dilated, and with the fetus in a high station).1,10–12 A caesarean section is usually performed after elective induction with an unripe cervix for the following indications: prolonged first stage of labour, fetal distress, failure to progress and intrapartum haemorrhage.13–15

Some adverse maternal outcomes have been associated with elective induction of labour. These include an increase in instrumental vaginal deliveries; greater need for epidural analgesia; postpartum haemorrhage; increased need for blood transfusion; longer hospital stays and higher hospital costs.12,14,16–19 In addition, the neonate requires immediate care and must sometimes be admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit (ICU), particularly when the cervix is unripe at delivery.15,17,19

Elective induction of labour is becoming increasingly common but is seldom directly reported in studies perhaps because of lack of consensus with respect to its definition. In some settings labour induction is reported as elective when it is performed without medical indication; in others, any pre-scheduled induction of labour, with or without medical indication, is considered elective. In the present analysis we use the term elective induction of labour when no medical indication for the procedure exists. Since this intervention may be associated with increased maternal and perinatal risks, knowing how frequently it is performed is important for taking steps towards preventing its associated problems and providing accurate information to both pregnant women and health-care professionals. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the frequency of elective induction of labour in Latin America; the procedure’s rate of success in achieving vaginal delivery; the factors determining its application and any associated unfavourable maternal and perinatal outcomes.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of data on elective labour induction in Latin America, as obtained from the 2004–2005 World Health Organization Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health (WHOGS). The protocol and methods used in the original study have been described in other publications.20,21 Briefly, the WHOGS is a cross-sectional study in which data were collected from medical records in 120 randomly selected health facilities from eight randomly selected countries in Latin America. In each country data were collected on every single woman who gave birth in every selected facility (n = 97 095) during a data collection period lasting two or three months (depending on the number of deliveries in the facility) in 2004–2005. The protocol was approved by WHO’s Scientific and Ethical Review Group and Ethics Review Committee. Informed consent was not individually requested since the data were taken anonymously from medical charts.21

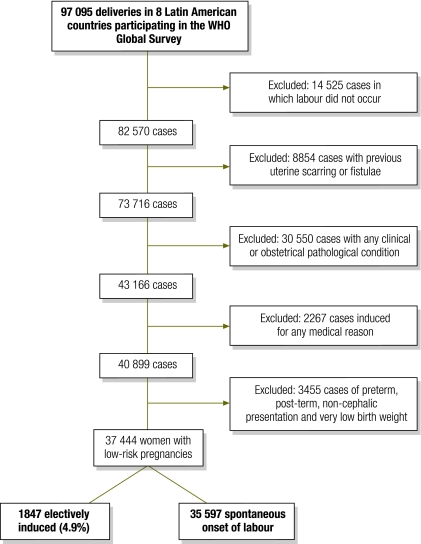

The database for this study included information from all the women in the 2004–2005 WHOGS. Although the original database indicated which inductions had been elective and/or performed at the mother’s request (totalling 3319 cases), we considered it fundamental for this analysis to select a low-risk population by excluding women who had risk factors that could have affected the delivery itself and its maternal and perinatal outcome. We therefore followed the steps in the flowchart shown in Fig. 1 to select a group of women with low-risk pregnancies who had undergone elective labour induction (at their own request or in the absence of any medical indication) as well as a group with spontaneous onset of labour. By using this strategy, we presumably excluded all inductions that were medically indicated and generated a low-risk sample of women undergoing induced labour. In this sample population we identified 1847 women with elective induction and compared them with the women with low-risk pregnancies (35 597) who went into labour spontaneously during the study period.

Fig. 1.

Steps used to identify women with low-risk pregnancies who had electively induced labour, as recorded in the 2004–2005 Global Survey for Latin America of the World Health Organization (WHO)

Statistical analysis

We first quantified successful elective labour inductions – i.e. inductions culminating in a vaginal delivery – as a function of the induction method used (i.e. oxytocin, misoprostol, another prostaglandin, artificial rupture of membranes, membrane sweeping, or a combination of methods). To assess maternal characteristics potentially predictive of elective labour induction (age, marital status, schooling, parity, type of delivery health-care facility, body mass index [BMI, expressed as kg/m2] and gestational age) we compared women whose labour was electively induced with women whose labour was spontaneous and calculated crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using multiple logistic regression models.

We calculated crude relative risks (RR) and adjusted relative risks (RRadj) and their respective 95% CIs for the following maternal outcomes and complications potentially associated with labour induction: mode of delivery, postpartum haemorrhage with blood transfusion; a need for uterotonic agents in the postpartum period; blood transfusion; perineal laceration; hysterectomy; admission to the ICU; duration of postpartum stay in hospital; use of analgesia/anaesthesia, and maternal status at discharge. We then used a logistic regression model that included adjustment for mode of delivery and all other predictors (except BMI because of the large number of cases that were missing this information). We followed exactly the same procedures to assess the following perinatal outcomes: a low 5th minute Apgar score; low birth weight; admission to the neonatal ICU; neonatal deaths taking place in hospital within the first week of life (as a proxy for early neonatal death) and time of initiation of breastfeeding. All the analyses were performed with the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software program, version 9.02 (SAS Institute, Cary, United States of America).

Results

Of the 11 077 inductions registered in the database, 16.7% were elective as per the definition used in this study. These elective inductions occurred in 4.9% of women with low-risk pregnancies (37 444). Table 1 shows that vaginal delivery was attained in 88.2% of all elective inductions, with little variation among the different methods of induction used. Oxytocin administration was the single most frequently used induction method (65.9%), whereas misoprostol was used to induce only 8.9% of the deliveries. Other prostaglandins, membrane sweeping and artificial rupture of membranes were rarely used.

Table 1. Elective inductions of labour culminating in vaginal or Caesarean delivery, by method of induction, in women with low-risk pregnancies in selected Latin American countries, 2005.

| Induction method | Total | Vaginal |

Caesarean |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Oxytocina | 1219 | 1093 | 89.7 | 126 | 10.3 | |

| Combinedb | 409 | 362 | 88.5 | 47 | 11.5 | |

| Misoprostol | 165 | 128 | 77.6 | 36 | 21.8 | |

| Other prostaglandin | 33 | 27 | 81.8 | 6 | 18.2 | |

| Artificial ROM | 19 | 18 | 94.7 | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Membrane sweeping | 2 | 1 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | |

| Total | 1847 | 1629 | 88.2 | 217 | 11.7 | |

ROM, rupture of membranes.

a One case with no information on mode of delivery.

b Of these cases, 329 correspond to oxytocin plus another method.

Table 2 shows that not having a partner was associated with a reduced risk of having an elective induction. On the other hand, nulliparity and giving birth in social security or private health-care institutes increased the risk of having an elective induction. A woman’s age and educational level showed no association with the risk of elective induction. Although a BMI > 30 was also associated with an increased likelihood of having an elective induction, it could not be determined from the logistic regression if obese women have an intrinsic risk of elective induction of labour because a substantial proportion of data were missing. All women were at term, between 37 and 40 weeks of gestational age.

Table 2. Crude odds ratios (OR) and adjusted odds ratios (ORadj) of elective labour induction in women with low-risk pregnancies, by demographic and other characteristics, in selected Latin American countries, 2005.

| Characteristic | Spontaneous onset of labour |

Elective induction |

OR (95% CI) | ORadj (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 10–19 | 369 | 19.99 | 7666 | 21.55 | 0.90 (0.80–1.01) | 0.96 (0.84–1.10) | |

| 20–34 | 1347 | 72.97 | 25 181 | 70.77 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| ≥ 35 | 130 | 7.04 | 2733 | 7.68 | 0.89 (0.74–1.07) | 0.98 (0.77–1.24) | |

| Missing | 1 | – | 17 | – | – | – | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Having a partner | 26 668 | 75.27 | 1513 | 81.96 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| No partner | 8762 | 24.73 | 333 | 18.04 | 0.67 (0.59–0.76) | 0.76 (0.67–0.87) | |

| Missing | 167 | – | 1 | – | – | – | |

| Years of schooling | |||||||

| < 7 | 9649 | 28.72 | 488 | 28.82 | 0.92 (0.77–1.11) | 1.10 (0.91–1.34) | |

| 7–12 | 21 073 | 62.72 | 1047 | 61.85 | 0.90 (0.76–1.07) | 1.06 (0.89–1.26) | |

| > 12 | 2877 | 8.56 | 158 | 9.33 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Missing | 1998 | – | 154 | – | – | – | |

| Parity | |||||||

| Primipara | 15 565 | 43.81 | 828 | 44.83 | 1.05 (0.95–1.17) | 1.13 (1.01–1.27) | |

| 2–3 deliveries | 15 232 | 42.87 | 769 | 41.64 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| > 3 deliveries | 4734 | 13.32 | 250 | 13.54 | 1.05 (0.90–1.21) | 1.07 (0.91–1.26) | |

| Missing | 66 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Health-care facility | |||||||

| Public | 26 734 | 75.10 | 1047 | 56.68 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Social security | 6118 | 17.19 | 666 | 36.06 | 2.78 (2.51–3.08) | 2.90 (2.61–3.22) | |

| Private | 2741 | 7.71 | 134 | 7.26 | 1.25 (1.04–1.50) | 1.85 (1.47–2.32) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| ≤ 30 | 16 334 | 59.22 | 890 | 56.12 | 1.00 | Not usedb | |

| > 30 (obesity) | 11 250 | 40.78 | 696 | 43.88 | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) | – | |

| Missing | 8013 | – | 261 | – | – | – | |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval.

a Simple and multiple logistic regression model (including all variables except BMI).

b BMI was not used in multiple analyses due to the high number of cases in which data were missing.

Caesarean sections were performed in 11.8% of women with low-risk pregnancies who underwent elective labour induction, as opposed to 8.6% of women who went into labour spontaneously. Despite the fact that higher caesarean section rates were observed among women undergoing elective induction of labour (crude RR: 1.36; 95% CI: 1.19–1.55), the intrinsic risk of this procedure was only marginally associated with caesarean section (RRadj: 1.16; 95% CI: 1.00–1.35). The maternal complications most associated with elective induction of labour among women with low-risk pregnancies, confirmed by multiple logistic regression analysis, were: postpartum need for uterotonic drugs (a 1.5-fold greater risk); hysterectomy (a 5.2-fold greater risk, although this figure comes from only 4 cases among women with elective induction); admission to the ICU (a 3-fold greater risk), and a greater need for anaesthetic and analgesic procedures. On the other hand, elective induction was not associated with an increased risk of perineal laceration or postpartum haemorrhage, lengthened hospital stay or a greater need for blood transfusion (Table 3).

Table 3. Crude relative risk (RR) and adjusted relative risk (RRadj) of specific maternal outcomes in women with low-risk pregnancies who underwent elective labour induction in selected Latin American countries, 2005.

| Maternal outcome | Elective induction |

Spontaneous onset of labour |

RR (95% CI) | RRadj (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||||

| Mode of delivery | |||||||

| Vaginal | 1629 | 88.25 | 32 506 | 91.35 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Caesarean | 217 | 11.75 | 3077 | 8.65 | 1.36 (1.19–1.55) | 1.16 (1.00–1.35) | |

| Missing | 1 | – | 14 | – | – | – | |

| Postpartum haemorrhage with blood transfusion | |||||||

| No | 1820 | 99.67 | 34 796 | 99.72 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 6 | 0.33 | 97 | 0.28 | 1.18 (0.52–2.69) | 1.34 (0.58–3.09) | |

| Missing | 21 | – | 704 | – | – | – | |

| Need for uterotonics during postpartum period | |||||||

| No | 1206 | 65.58 | 27 926 | 78.87 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 633 | 34.42 | 7483 | 21.13 | 1.63 (1.52–1.74) | 1.52 (1.39–1.66) | |

| Missing | 8 | – | 188 | – | – | – | |

| Blood transfusion | |||||||

| No | 1823 | 99.08 | 35 224 | 99.47 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 17 | 0.92 | 188 | 0.53 | 1.74 (1.06–2.85) | 1.50 (0.91–2.47) | |

| Missing | 7 | – | 185 | – | – | – | |

| Perineal laceration | |||||||

| No | 1827 | 99.40 | 35 184 | 99.52 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 11 | 0.60 | 171 | 0.48 | 1.24 (0.67–2.27) | 1.46 (0.78–2.70) | |

| Missing | 9 | – | 242 | – | – | – | |

| Hysterectomy | |||||||

| No | 1834 | 99.78 | 35 340 | 99.96 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 4 | 0.22 | 13 | 0.04 | 5.92 (1.93–18.13) | 5.23 (1.62–16.86) | |

| Missing | 9 | – | 244 | – | – | – | |

| Admission to ICU | |||||||

| No | 1838 | 99.67 | 35 491 | 99.83 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 6 | 0.33 | 61 | 0.17 | 1.90 (0.82–4.38) | 2.90 (1.24–6.78) | |

| Missing | 3 | – | 45 | – | – | – | |

| Postpartum stay | |||||||

| < 7 days | 1832 | 99.35 | 35 190 | 98.99 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| ≥ 7 days | 12 | 0.65 | 358 | 1.01 | 0.65 (0.36–1.15) | 0.82 (0.46–1.45) | |

| Missing | 3 | – | 49 | – | – | – | |

| Anaesthesia during labour | |||||||

| No anaesthesia/analgesia | 950 | 52.25 | 27 258 | 76.98 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Epidural | 332 | 18.18 | 3972 | 11.22 | 2.03 (1.48–2.24) | 1.58 (1.40–1.79) | |

| Spinal | 29 | 1.59 | 337 | 0.95 | 2.42 (1.66–3.51) | 1.28 (0.84–1.95) | |

| Parenteral analgesic | 341 | 18.67 | 2280 | 6.44 | 3.41 (3.09–3.77) | 3.01 (2.65–3.41) | |

| Alternative methods | 170 | 9.31 | 1561 | 4.41 | 2.79 (2.41–3.23) | 3.66 (3.12–4.29) | |

| Missing | 21 | – | 189 | – | – | – | |

| Status at discharge | |||||||

| Alive | 1842 | 99.84 | 35 550 | 99.92 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Dead | 0 | – | 1 | – | – | – | |

| Referred to higher level | 3 | 0.16 | 28 | 0.08 | 2.07 (0.63–6.79) | 2.08 (0.62–6.96) | |

| Missing | 2 | – | 18 | 0.10 | – | – | |

CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit.

a Cox regression model with adjustment for mode of delivery and all predictors in Table 2 except body mass index.

Four women who had elective induction of labour had a hysterectomy; two of them were nulliparas and all had been induced with oxytocin. Two of the four women required uterotonics in the postpartum period and received blood transfusions. None had to be admitted to the ICU. Thirteen hysterectomies occurred among women who had spontaneous labour. Of these 13 women, 10 were multiparas, 4 had postpartum haemorrhage, 8 required uterotonics postpartum, 7 required blood transfusions and 4 were admitted to the ICU. Ten of these women had vaginal deliveries. Only one of the women whose labour was spontaneous died. This was a 20-year old primigravida at full term who had received appropriate prenatal care and in whom no risk factors had been identified. She had a vaginal delivery of a full-term, healthy infant with good vital signs (data not shown).

Finally, Table 4 shows that elective induction among women with low-risk pregnancies was not significantly associated with an increased risk of most neonatal complications, including a low 5th minute Apgar score, low birth weight, admission to a neonatal ICU or early neonatal death. Nevertheless, delayed initiation of breastfeeding (i.e. initiation between one hour and seven days postpartum) was more common among women who had an elective induction of labour, with a mean 22% higher risk (RR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.12–1.34). In addition, the mean birth weight of neonates did not significantly vary between groups (elective induction group: 3259.6 g [standard deviation, SD: ± 417.3]; spontaneous onset of labour group: 3254.6 g [SD: ± 430.1]) (P = 0.63, data not shown).

Table 4. Crude relative risk (RR) and adjusted relative risk (RRadj) of adverse perinatal outcomes in women with low-risk pregnancies who underwent elective labour induction in selected Latin American countries, 2005.

| Perinatal outcome | Elective induction |

Spontaneous onset of labour |

RR (95% CI) | RRadj (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||||

| 5th minute Apgar | |||||||

| < 7 | 18 | 0.98 | 366 | 1.03 | 0.95 (0.59–1.51) | 1.06 (0.66–1.71) | |

| ≥ 7 | 1824 | 99.02 | 35 040 | 98.97 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Missing | 5 | – | 191 | – | – | – | |

| Birth weightb (g) | |||||||

| < 2 500 | 54 | 2.93 | 1158 | 3.26 | 0.90 (0.69–1.18) | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) | |

| ≥ 2 500 | 1791 | 97.07 | 34 384 | 96.74 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Missing | 2 | – | 55 | – | – | – | |

| Admission to neonatal ICU | |||||||

| No | 1754 | 95.69 | 33 886 | 95.50 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 79 | 4.31 | 1596 | 4.50 | 0.96 (0.77–1.20) | 1.06 (0.85–1.34) | |

| Missing | 14 | – | 115 | – | – | – | |

| Early neonatal death | |||||||

| Alive | 1845 | 100.0 | 35 463 | 99.92 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Early neonatal death | 0 | – | 30 | 0.08 | – | – | |

| Missing | 2 | – | 104 | – | – | – | |

| Breastfeeding started | |||||||

| Within first hour | 989 | 53.69 | 20 800 | 58.88 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 1–24 hours after birth | 739 | 40.12 | 13 440 | 38.04 | 1.09 (1.03–1.15) | 1.10 (1.02–1.19) | |

| After the first day | 69 | 3.75 | 841 | 2.38 | 1.68 (1.32–2.13) | 1.59 (1.24–2.05) | |

| Not before 7th day | 45 | 2.44 | 246 | 0.70 | 3.72 (2.73–5.08) | 3.14 (2.28–4.34) | |

| Missing | 5 | – | 270 | – | – | – | |

CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit.

a Cox regression model with adjustment for mode of delivery and all predictors in Table 2 except body mass index.

b Low birth weight: < 2500 g.

Discussion

In this study, a substantial proportion of labour inductions were performed without medical indication or at the mother’s request. Women with low-risk pregnancies who underwent elective induction of labour had an increased risk of adverse outcomes. In fact, we were surprised to find that in 30% of all cases of induced labour contained in the database, “elective” and “by request” were the terms used for the indication, even in some cases that were medically justified. Countries varied, however, in the extent to which they used these terms. We then restricted the sample to women with low-risk pregnancies by excluding all inductions that were medically indicated or that were performed in women with a pathological condition during pregnancy or delivery or with a history of uterine scarring, breech presentation or any other obstetric complication. In this way we obtained a smaller sample and the fraction of elective inductions decreased. This approach, also used by other authors,3,22 is considered the only acceptable method for comparing pregnant women whose induction was genuinely elective with other women with low-risk pregnancies delivering spontaneously.

The success of elective induction

The mean caesarean section rate in the elective inductions was 11.7%, well below the caesarean rate of 29.5% for the sum of all inductions in this same population. This rate of caesarean section is low considering current standards, perhaps because elective induction was performed only in the presence of a favourable cervix, as recommended by Bishop;23 however, this aspect was not evaluated in the present study. We believe this may have been the case because oxytocin is generally effective only when the cervix is favourable for induction and in this study oxytocin, alone or in combination with another method, was the agent most commonly used to induce labour. However, we are unable to exclude the possibility that misoprostol was less available or that practitioners felt less confident in using it. Misoprostol, which is most frequently indicated when the cervix needs to be prepared, was used alone in only 8.9% of the pregnant women, and the caesarean section rate among women given misoprostol was 21.8%, twice as high as the rate after induction with oxytocin. These results indirectly corroborate findings from other studies to the effect that elective induction in the presence of an unripe cervix constitutes a risk factor for caesarean section.19,24–26

Predictive factors

In this sample of women with low-risk pregnancies, maternal age was not associated with elective induction, contrary to findings published by other investigators who reported that age below 19 years was a protective factor.3,8,10,27 Not having a partner was a factor associated with a reduced risk of elective induction, and this corroborates the findings of Coonrod et al.8 On the other hand, maternal educational level was not associated with elective induction in our study population, a finding in agreement with the findings of Boulvain et al.10 and Le Ray et al.26 but in disagreement with those of Coonrod et al.,8 who reported a greater risk of elective induction in women with more than 12 years of schooling. However, only 9% of the women in our study fell into this category.

Nulliparity was an independent risk factor for elective labour induction. This finding conflicts with reports from other authors who found a protective effect.3,10,26 Giving birth in a private or social security institution was associated with a double or triple risk of elective induction, a finding also in agreement with reports from other studies.3,26,28

Outcomes

Higher rates of caesarean section were observed among women who underwent elective induction of labour. After adjustment for other risk factors, elective induction of labour remained marginally associated with an intrinsic risk of caesarean section. Uterotonic agents in the postpartum period were more often needed after elective inductions than after spontaneous initiation of labour. This last finding should be interpreted with caution, however, because elective induction was not associated with an increased risk of puerperal haemorrhage requiring blood transfusion. Moreover, the same uterotonic drugs can continue to be used through the third and fourth stages of labour prophylactically, not necessarily to control new haemorrhage.

The most important finding of this study is perhaps the fivefold increase in hysterectomies among women who underwent elective labour induction. Although hysterectomy was infrequent both in absolute and in relative terms, this finding is worrisome because labour induction was theoretically not medically indicated in these cases and culminated in a procedure with high morbidity that puts an end to a woman’s reproductive life. In fact, some authors have reported a higher risk of hysterectomy during labour induced inappropriately with misoprostol and a higher risk of uterine rupture in association with the induction itself.29–32 The four women who underwent elective induction followed by a hysterectomy were all induced with oxytocin. This reinforces some authors’ views that uterotonics have to be used with caution.31,32 This finding should be cautiously interpreted in light of the very small number of hysterectomies (i.e. the finding may be unstable)

Elective induction of labour has also been associated with a greater need for anaesthesia, which interferes with the natural process of delivery even in the absence of maternal complications or other adverse situations, and also carries inherent risks and increased costs.14,17,18

There was no difference between the two groups with respect to the 5th minute Apgar score, even after adjustment for all predictor variables. This finding corroborates reports from various other authors.10,13,24,33 In the current study, elective induction did not show a significant association with low birth weight. Finally, elective induction in this study was associated with late initiation of breastfeeding.

Conclusions

In this study, elective induction was practised at a rate similar to the rates reported in developed countries, around 10%.1,2,4 Although perinatal outcomes were similar among women who underwent elective induction of labour and those whose labour was spontaneous, women who had induced labour had increased rates of caesarean section and, more importantly, of hysterectomy. Therefore, caution should be exercised when inducing labour without any medical indication, since no clear benefits outweigh the associated risk of an adverse maternal outcome.

Acknowledgements

We thank all those people who were involved in the planning, implementation, data collection, analysis and reporting of the 2004–2005 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health in Latin America.

Funding:

The original study was funded by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and WHO’s Department of Reproductive Health and Research. The current analysis was sponsored by the University of Campinas, Brazil.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Yeast JD, Jones A, Poskin M. Induction of labor and the relationship to cesarean delivery: A review of 7001 consecutive inductions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:628–33. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70265-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rayburn WF, Zhang J. Rising rates of labor induction: present concerns and future strategies. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:164–7. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lydon-Rochelle MT, Cárdenas V, Nelson JC, Holt VL, Gardella C, Easterling TR. Induction of labor in the absence of standard medical indications: incidence and correlates. Med Care. 2007;45:505–12. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180330e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rayburn WF. Minimizing the risks from elective induction of labor. J Reprod Med. 2007;52:671–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez-Ramos L. Induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2005;32:181–200, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goffinet F, Dreyfus M, Carbonne B, Magnin G, Cabrol D. Survey of the practice of cervical ripening and labor induction in France. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2003;32:638–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blair EM. Induction of labour by rupture of the membranes. Can Med Assoc J. 1936;34:49–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coonrod DV, Bay RC, Kishi GY. The epidemiology of labor induction: Arizona, 1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1355–62. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salinas PH, Carmona GS, Albornoz VJ, Veloz RP, Terra VR, Marchant GR, et al. ¿Se puede reducir el índice de cesárea? Experiencia del hospital clínico de la Universidad de Chile. Rev Chil Obstet Ginecol. 2004;69:8–15. Spanish. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boulvain M, Marcoux S, Bureau M, Fortier M, Fraser W. Risks of induction of labour in uncomplicated term pregnancies. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:131–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson DP, Davis NR, Brown AJ. Risk of cesarean delivery after induction at term in nulliparous women with an unfavorable cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1565–72. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battista L, Chung JH, Lagrew DC, Wing DA. Complications of labor induction among multiparous women in a community-based hospital system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:241.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macer JA, Macer CL, Chan LS. Elective induction versus spontaneous labor: a retrospective study of complications and outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1690–6, discussion 1696-7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91558-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glantz JC. Elective induction vs. spontaneous labor associations and outcomes. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:235–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan PC, Suguna S, Vallikkannu N, Hassan J. Predictors of newborn admission after labour induction at term: Bishop score, pre-induction ultrasonography and clinical risk factors. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:193–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dublin S, Lydon-Rochelle M, Kaplan RC, Watts DH, Critchlow CW. Maternal and neonatal outcomes after induction of labor without an identified indication. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:986–94. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cammu H, Martens G, Ruyssinck G, Amy JJ. Outcome after elective labor induction in nulliparous women: a matched cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:240–4. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.119643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufman KE, Bailit JL, Grobman W. Elective induction: an analysis of economic and health consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:858–63. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vrouenraets FP, Roumen FJ, Dehing CJ, van den Akker ES, Aarts MJ, Scheve EJ. Bishop score and risk of cesarean delivery after induction of labor in nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:690–7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000152338.76759.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, Zavaleta N, Carroli G, Velazco A, et al. WHO 2005 global survey on maternal and perinatal health research group Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet. 2006;367:1819–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68704-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah A, Faundes A, Machoki M, Bataglia V, Amokrane F, Donner A, et al. Methodological considerations in implementing the WHO Global Survey for Monitoring Maternal and Perinatal Health. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:126–31. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.039842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson BL. Assessing the effects of age, gestation, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity on labor inductions. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:208–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bishop EH. Elective induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1955;5:519–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prysak M, Castronova FC. Elective induction versus spontaneous labor: a case-control analysis of safety and efficacy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:47–52. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(98)00115-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vahratian A, Zhang J, Troendle JF, Sciscione AC, Hoffman MK. Labor progression and risk of cesarean delivery in electively induced nulliparas. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:698–704. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000157436.68847.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Ray C, Carayol M, Bréart G, Goffinet F, PREMODA Study Group Elective induction of labor: failure to follow guidelines and risk of cesarean delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:657–65. doi: 10.1080/00016340701245427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J, Yancey MK, Henderson CEUS. U.S. national trends in labor induction, 1989–1998. J Reprod Med. 2002;47:120–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beebe LA, Rayburn WF, Beaty CM, Eberly KL, Stanley JR, Rayburn LA. Indications for labor induction. Differences between university and community hospitals. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:469–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennett BB. Uterine rupture during induction of labor at term with intravaginal misoprostol. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:832–3. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanchette HA, Nayak S, Erasmus S. Comparison of the safety and efficacy of intravaginal misoprostol (prostaglandin E1) with those of dinoprostone (prostaglandin E2) for cervical ripening and induction of labor in a community hospital. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1551–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kacmar J, Bhimani L, Boyd M, Shah-Hosseini R, Peipert J. Route of delivery as a risk factor for emergent peripartum hysterectomy: a case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:141–5. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(03)00404-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaczmarczyk M, Sparén P, Terry P, Cnattingius S. Risk factors for uterine rupture and neonatal consequences of uterine rupture: a population-based study of successive pregnancies in Sweden. BJOG. 2007;114:1208–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Gemund N, Hardeman A, Scherjon SA, Kanhai HH. Intervention rates after elective induction of labor compared to labor with a spontaneous onset. A matched cohort study. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2003;56:133–8. doi: 10.1159/000073771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]