Abstract

Objective

To examine the feasibility of using community health workers (CHWs) to implement cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention programmes within faith-based organizations in Accra, Ghana.

Methods

Faith-based organization capacity, human resources, health programme sustainability/barriers and community members’ knowledge were evaluated. Data on these aspects were gathered through a mixed method design consisting of in-depth interviews and focus groups with 25 church leaders and health committee members from five churches, and of a survey of 167 adult congregants from two churches.

Findings

The delivery of a CVD prevention programme in faith-based organizations by CHWs is feasible. Many faith-based organizations already provide health programmes for congregants and involve non-health professionals in their health-care activities, and most congregants have a basic knowledge of CVD. Yet despite the feasibility of the proposed approach to CVD prevention through faith-based organizations, sociocultural and health-care barriers such as poverty, limited human and economic resources and limited access to health care could hinder programme implementation.

Conclusion

The barriers to implementation identified in this study need to be considered when defining CVD prevention programme policy and planning.

ملخص

الغرض

دراسة إمكانية استخدام العاملين في صحة المجتمع في تنفيذ برامج الوقاية من المرض القلبي الوعائي في المنظمات الدينية في أكرا في غانا.

الطريقة

جرى تقييم قدرات المنظمات الدينية، ومواردها البشرية، وضمان استمرار البرنامج الصحي والعقبات التي تواجهه، ومعارف أعضاء المجتمع. وجُمعت المعطيات حول هذه الجوانب عبر طريقة تصميم مختلطة تتكون من مراجعات معمَّقة ومجموعات بؤرية من 25 رئيس كنيسة وأعضاء اللجنة الصحية في خمس كنائس، ومن مسح ضم 167 عضواً في محفل كنيستين.

النتائج

من الممكن تقديم برنامج الوقاية من المرض القلبي الوعائي في المنظمات الدينية عبر العاملين في صحة المجتمع. فكثير من المنظمات الدينية تقدّم بالفعل برامج صحية لأعضاء محفلها، وتُشْرِك المهنيين غير الصحيين في أنشطتها للرعاية الصحية، ولدى غالبية أعضاء المحفل معارف أساسية حول المرض القلبي الوعائي. ولكن مع إمكانية تحقيق الأسلوب المقترح للوقاية من المرض القلبي الوعائي عن طريق المنظمات الدينية، فإن العقبات الاجتماعية والثقافية والرعاية الصحية مثل الفقر، وقلة الموارد البشرية والاقتصادية، وندرة الوصول إلى الرعاية الصحية يمكن أن يعيق تنفيذ البرنامج.

الاستنتاج

إن العقبات أمام التنفيذ التي جرى التعرّف عليها في هذه الدراسة تستدعي مراعاتها عند تحديد سياسات وخطط برنامج الوقاية من المرض القلبي الوعائي.

Resumen

Objetivo

Examinar la viabilidad de utilizar a trabajadores sanitarios de la comunidad (TSC) para implementar diversos programas de prevención de enfermedades cardiovasculares (ECV) en organizaciones religiosas en Accra, Ghana.

Métodos

Se evaluaron la capacidad de la organización religiosa, los recursos humanos, la sostenibilidad y los impedimentos del programa sanitario, así como los conocimientos de los miembros de la comunidad. Los datos sobre estos aspectos se recopilaron a través de un diseño de método combinado compuesto por entrevistas en profundidad y grupos de enfoque con 25 líderes religiosos y miembros del comité sanitario procedentes de cinco iglesias, así como por una encuesta realizada a 167 feligreses adultos de dos iglesias.

Resultados

Consideramos viable la aplicación por parte de los trabajadores sanitarios de la comunidad de un programa de prevención de ECV en organizaciones de carácter religioso. Muchas organizaciones de tipo religioso ya ofrecen programas sanitarios para sus feligreses e implican a profesionales no sanitarios en sus actividades sanitarias. Además, la mayoría de los feligreses tienen conocimientos básicos sobre las ECV. A pesar de la viabilidad del enfoque propuesto para la prevención de las ECV a través de organizaciones de carácter religioso, diversos impedimentos socioculturales y sanitarios como la pobreza, la escasez de recursos humanos y económicos, así como el acceso limitado a la asistencia sanitaria podrían obstaculizar la aplicación del programa.

Conclusión

Los obstáculos para la aplicación identificados en este estudio deberán tenerse en cuenta a la hora de definir la normativa y planificación del programa de prevención de las ECV.

Résumé

Objectif

Examiner la faisabilité de l’utilisation d’agents communautaires de santé (ACS) pour mettre en place des programmes de prévention des maladies cardiovasculaires (MCV) au sein d’organisations religieuses d’Accra, au Ghana.

Méthodes

La capacité des organisations religieuses, les ressources humaines, la durabilité/les barrières des programmes de santé et les connaissances des membres de la communauté ont été évaluées. Les données de ces différents aspects ont été recueillies par le biais d’une conception de méthode mixte, consistant en des entretiens approfondis et des groupes cibles avec 25 responsables d’église et membres du comité de santé de 5 églises, ainsi qu’une étude de 167 fidèles adultes de 2 églises.

Résultats

La mise en place d’un programme de prévention des MCV dans les organisations religieuses par des ACS est faisable. De nombreuses organisations religieuses offrent déjà des programmes de santé aux fidèles et impliquent des personnes qui ne sont pas des professionnels de la santé dans leurs activités de soins. De plus, la plupart des fidèles ont des connaissances de base des MCV. Cependant, malgré la faisabilité de l’approche proposée dans le cadre de la prévention des MCV par les organisations religieuses, des barrières socioculturelles et sanitaires, comme la pauvreté, des ressources économiques et humaines limitées, ainsi qu’un accès restreint aux soins de santé, pourraient entraver la mise en place du programme.

Conclusion

Les barrières à la mise en place identifiées dans cette étude doivent être prises en compte pour définir la politique et la planification des programmes de prévention des MCV.

Резюме

Цель

Изучить применимость использования общинных медико-санитарных работников (ОМСР) для осуществления профилактических программ в отношении кардиоваскулярных заболеваний (КВЗ) в конфессиональных организациях в Аккре, Гана.

Методы

Была проведена оценка потенциала конфессиональных организаций, человеческих ресурсов, устойчивости/барьеров на пути применения программ в области здравоохранения и знания членов общин. По всем этим аспектам были собраны данные с использованием сочетания различных методов, включавших подробное интервьюирование и фокус-группы, охвативших 25 руководителей церквей и членов комитетов здравоохранения из пяти церквей, а также обследование 167 взрослых членов двух церковных общин.

Результаты

Использование программ профилактики КВЗ в конфессиональных организациях с привлечением ОМСР возможно. Многие конфессиональные организации уже применяют программы в области здравоохранения среди своих членов и привлекают к своей деятельности в области охраны здоровья персонал, не имеющий медицинского образования, а многие члены конфессий обладают основами знаний о ВКЗ. Несмотря на применимость предлагаемого подхода к профилактике ВКЗ через конфессиональные организации, социокультурные препятствия и барьеры на пути получения услуг самой системы здравоохранения, такие как бедность, ограниченные человеческие и экономические ресурсы, а также ограниченный доступ к услугам здравоохранения могут затруднять осуществление программы.

Вывод

Барьеры на пути осуществления, указанные в данном исследовании, должны приниматься во внимание при выборе конкретных мер политики профилактики КВЗ и ее планировании.

摘要

目的

本文旨在探讨通过加纳阿克拉的宗教组织,利用社区卫生工作者(CHWs)实施心血管疾病预防方案的可行性。

方法

对宗教组织的能力、人力资源、卫生方案可持续性/阻碍及社区成员所具备的知识进行评估。以上方面的数据通过多种方法设计进行收集,包括与25名教会领袖及5个教会的卫生委员会成员进行深入访谈和小组讨论,以及对两个教会的167名成人教友进行一项调查。

结果

在宗教组织中由社区卫生工作者实施心血管疾病预防方案是可行的。许多宗教组织已经为其成员提供卫生计划,并使得非卫生专业人士参与到他们的卫生保健活动中,而且多数教会成员具备心血管疾病的基本知识。尽管通过宗教组织实施心血管疾病预防方案是可行的,但是,贫困、人力资源及经济资源有限、医疗保健条件有限等社会文化和卫生保健方面的障碍,可能会阻碍方案的实施。

结论

在制定心血管疾病预防政策和规划时,应考虑本项研究所指出的方案执行障碍。

Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa, cardiovascular disease (CVD) has risen dramatically and has become a leading cause of morbidity and mortality.1–3 According to The world health report, in 2001 CVD accounted for 9.2% of all deaths in the African region.4 In Accra, Ghana, CVD was the leading cause of death in 1991 and 2001.5

While communicable diseases continue to drain health resources in sub-Saharan Africa, the rising CVD epidemic poses a new public health challenge. Poverty and health-care worker shortages have seriously hindered the response to this mounting non-communicable disease burden.2,6–8 Cost-effective strategies to prevent, detect and control CVD are urgently needed.

To address the critical shortage of health professionals and increase access to health care, Ghana’s Ministry of Health has begun to utilize community health workers (CHWs). Since 2000, volunteer-based CHW programmes have been included in Ghana’s Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) initiative, a national policy programme that was developed to mobilize resources to support community-based primary care.9The CHPS requires six steps: (i) preliminary planning, (ii) community entry, (iii) creating community health compounds, (iv) posting community health officers to community health compounds to provide health services, (v) procuring essential equipment, and (vi) training CHW volunteers.9,10

Surveillance statistics for the CHPS showed that in 2008 the programme was being more widely implemented in regions with fewer health-care resources than Accra, even though in this city the programme would be more beneficial because the prevalence of CVDs is higher.5 Nyonator et al. attribute this and the lack of training of volunteer CHWs in Accra to concerns about sustainable funding.9,11 Thus, a new way of thinking in connection with the CHW model for CVD prevention in Accra may be needed.

The development of CHW programmes within faith-based organizations may be an alternative approach for Ghana. This is supported by the fact that: (i) faith-based organizations have successfully run programmes for the primary prevention of CVD and cancer in developed countries,12 and for HIV/AIDS prevention, screening and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa;13–17 (ii) a large percentage of Ghanaians attend activities in faith-based organizations;18 and (iii) faith-based organizations consider it their mission to increase their parishioners’ awareness of social issues, including health care. Indeed, the Christian Health Association of Ghana, a nongovernmental organization, provides 42% of the health services in the country.19 However, we know of no reports documenting organized efforts to conduct CVD prevention within Ghanaian faith-based organizations.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of having CHWs implement CVD prevention programmes in faith-based organizations in Accra. Our feasibility assessment considered four dimensions: (i) the context of programme delivery (a faith-based organization); (ii) the people delivering the programme (CHWs); (iii) barriers to implementation and sustainability; and (iv) influential factors related to the target population (e.g. community members’ knowledge about CVD). We studied four specific research questions:

Do faith-based organizations have the capacity to deliver CVD prevention programmes?

Is it feasible to engage CHWs to deliver CVD prevention programmes in faith-based organizations?

What barriers could hinder the implementation and undermine the sustainability of a CVD prevention programme within a faith-based organization?

What do church members know about CVD?

Methods

We used a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods.20 The first included in-depth interviews and focus groups with church leaders and health committee members which served to explore these individuals’ views on CVD and health programmes within faith-based organizations. The second, which consisted of administering a survey questionnaire to church health committee members and congregants, provided individual background information and a standardized assessment of their knowledge of CVD. We then compared the results obtained through the qualitative and quantitative approaches.

Sample

Our sample consisted of church leaders, church health committee members and other congregants in Accra, Ghana. Participants were recruited through both convenience and snowball sampling techniques, with churches selected on the basis of their availability through active recruitment and network referral.21 The only inclusion criterion for participants was that they be at least 18 years of age.

Five Christian churches in Accra (one Pentecostal, one Charismatic, one Baptist and two Presbyterian) whose congregations ranged from 200 to 1500 members participated. Four of the churches had local congregants and were being used as community spaces for a variety of group activities, while one church had congregants not only from Accra but also from other areas through real-time use of the radio and the internet. Three churches had been in their locales for more than five years and two of them for less than three years.

Thirteen church leaders (from five churches), 12 church health committee members (from four churches) and 167 congregants (from two churches) participated in the study. Of the church leaders and health committee members, only two had worked as CHWs; 76% were male and 24% were female and their mean age was 41 years (standard deviation, SD: 9.20). A primary-, secondary- and tertiary-level education had been attained by 9%, 27% and 55%, respectively. Of the congregants, 37% were male and 63% female and their mean age was 39 years (SD: 14.75). A primary-, secondary- and tertiary-level education had been attained by 15%, 36% and 38%, respectively, while 6% had received no education and 5% had attended technical or vocational school.

Data collection

Data were collected through interviews, focus groups and surveys at the participating churches in January of 2010. All five churches were located in the dense, urban area of Accra, Ghana’s capital city. In each of the five churches we interviewed the church leader(s) and held a focus group with church health committee members. We also surveyed health committee members from five churches and congregants from two churches. Each focus group had from 2 to 9 participants; group sizes varied because the churches differed in size and administrative structure. Each interview or focus group lasted from 1 to 1.5 hours and was conducted in English (the official language in Ghana), audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. Each survey took approximately 10 minutes to complete.

During each interview and focus group we asked church leaders and health committee members to share their knowledge and beliefs about CVD, their experiences in managing health-related programmes and their ideas in connection with implementing CVD prevention programmes in faith-based organizations.

A CVD knowledge questionnaire (27 items adapted from Arikan et al.)22 was used to assess congregants’ knowledge of CVD risks, symptoms and management. The questionnaire had adequate internal consistency (a measure of scale reliability) with a Cronbach’s α of 0.77. Health committee members completed the knowledge survey before participating in the focus group; church members completed it after Sunday church services.

Analyses

The first four authors analysed the qualitative data using grounded theory.21,23 This approach uses data triangulation21 from multiple data sources (e.g. church leaders, health committee members, congregant survey) and a “constant comparative method”,23 continually examining the analytic results against the raw data. Codes were derived from the transcription and then grouped into concepts or themes. We used no software. We conducted qualitative data analyses in two stages: (i) within each church, and (ii) across churches, with an examination of variations in the different types of churches. Four coders read through all data independently. We examined the results across churches to identify patterns and common themes. Thematic development involved a search for “core consistencies or meanings” in the four dimensions being investigated.21,23

To optimize study rigour, on the day of each interview we conducted research team debriefings to discuss the interview process and address ethical concerns. We triangulated the data and performed auditing, and we recorded all analytic decisions, as well as discussions surrounding discrepancies among codes and consensus on the final codes and concepts. All interviewers, who were also the study investigators, had received extensive training in qualitative research. In accordance with the principles of qualitative research, we relied on direct quotes as much as possible to ground our findings and interpretations. Quantitative data analyses focused on knowledge in three areas: CVD risks, CVD symptoms and CVD prevention and treatment. We performed analyses by subgroups (e.g. health committee versus church member, male versus female, person with versus without a history of CVD).

Results

In the first stage of data analysis, we inspected codes and theme differences between church leaders and health committees. We found that both groups provided very similar and consistent answers. Therefore, we are only reporting the results of the cross-church analyses (Table 1).

Table 1. Emergent themes and illustrative quotes on cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention programmes within health-based organizations, extracted from interviews and focus groups conducted with church leaders and health committee members, Accra, Ghana, 2010.

| Domain, underlying dimension and theme | Quote |

|---|---|

| I. Capacity of faith-based organizations in health programme delivery | |

| A. Church leaders’ views on the church’s role in health | |

| 1.1. Provide education and increase awareness | a. “… I think the role of the church is to educate church members on the steps that they should take to prevent these diseases.” (Male leader, Church 2) |

| b. “Continuous education and awareness should be done all the time. A specialist should be invited to the church. By getting in touch with 200 people at a time they can increase awareness… We will be aware that if I do this or that, this will happen.” (Male health committee member, Church 5) | |

| 1.2. Provide screening | a. “The church will continue to do screening and education at the same time. These are the two areas that I think we can do and educate the members with disease that may affect them and when they are ready, to help them get out of it.” (Male leader, Church 4) |

| b. “… to raise awareness, because most of these people do not have symptoms, even though they have high blood pressure. They just live with it until something happens. But at that point it’s too late. So we think that the screening allows you to quickly identify them and then to do something about it.” (Male leader, Church 3) | |

| 1.3. Organize activities to help others achieve better health | a. “The church has a role in increasing sensitization, exercise classes, and helping organize health walks, maybe games.” (Female leader, Church 4) |

| b. “and exercises, yes ... after this programme was started they formed a keep-fit exercise ...” (Male health committee member, Church 5) | |

| B. Churches’ experiences and operation in health programme delivery | |

| 1.4. Programme accessibility | a. “…the programme is meant for the church members, but the door is open to anyone.” (Male leader, Church 2) |

| b. “…but it's not just for our members but for the full community (both members and non-members). We reach out to them, medical outreach.” (Male leader, Church 3) | |

| c. “Sometimes we have people from the neighbouring areas…some from Madina. People came from all over. The ones who were doing the screening, we overtaxed them because we did not expect such huge numbers…” (Male leader, Church 4) | |

| 1.5. Partnerships with external organizations and non-members | a. “We have help like the Lion’s…Sometimes the pharmaceutical companies also provided drugs. We call on other professionals to help also…we call them friends of the church.” (Female leader, Church 4) |

| b. “We have doctors. From Korle-Bu. They are not members. I think those who are members of this congregation are just about two.” (Male health committee member, Church 3) | |

| 1.6. Multiple influences on health programme content | a. “Depending on the kind of disease that is popping out. It’s basically what we hear…” (Male leader, Church 5) |

| b. “So the health committees can come up with the proposals on issues or topics that they will be treating this year.” (Male health committee member, Church 5) | |

| c. “…the programme is given to us from The Church of Ghana. They have their health programmes. They give us a topic, based on that we talk a lot about it.” (Female leader, Church 4) | |

| II. Feasibility of having CHWs deliver a CVD prevention programme in a faith-based organization | |

| 2.1. Role of lay person in church health programmes | a. “We train some of the youth to take blood pressure and they are able to do it satisfactorily…most of them are going back to school.” (Male leader, Church 4) |

| b. “their work is more on data entry and trying to organize the people, positioning them in the right place, and getting the right information…so we have people who are not really health professionals, but who are more interested in helping organize people, entering data for us.” (Male health committee member, Church 3) | |

| 2.2. Existence of a semi-CHW model | a. “…we have a special nurse and health personnel on that committee who give guidance to the rest of the membership.” (Male leader, Church 2) |

| b. “The medical outreach team is made up of doctors and nurses…the medical personnel don’t take money from us.” (Male health committee member, Church 3) | |

| c. “We have resource personnel…nurses, doctors and other health personnel…and we have students also in the church…we use them most of the time.” (Female health committee member, Church 4) | |

| d. “We have a three-person health committee…3 nurses…members of the congregation who are volunteers.” (Male leader, Church 1) | |

| III. Potential barriers to implementing or sustaining a CVD health programme in a faith-based organization | |

| 3.1. Limited resources | a. “We provide our own funds – the local churches. So we are local and if we want to do anything we provide the funds ourselves.” (Female leader, Church 4) |

| b. “…because we don’t have the resources and since we fall under the mother church, we talk to the big men over there and they come to assist.” (Male leader, Church 5) | |

| c. “We are always cutting our quota according to our sizes.” (Male leader, Church 2) | |

| d. “I think they need more…more programmes...like the mammograms…” (Male leader, Church 3) | |

| 3.2. Absence of formal monitoring and evaluation | a. “It depends on the response that comes from the church members…Yes at the end of the year we ask the various committees to come out or write their reports. OK…they don't ask the church members but you can see from the attendance … that … they are ok with the programme…” (Male leader, Church 2) |

| b. “if they were told to see a doctor, we make a follow-up phone call after 1 month to see if the recommendation was followed and if the person’s health improved.” (Male leader, Church 1) | |

| c. “…judging from the contributions…we can see that the programme helps. We realize that we don’t get more people complaining about the same sickness.” (Male leader, Church 5) | |

| 3.3. Poverty | a. “Maybe poverty is also part of it because you know the right diet but you cannot afford it. So you still go to the starches of the past…” (Female leader, Church 4) |

| b. “These economic hardships…people get stressed out.” (Male health committee member, Church 3) | |

| 3.4. Limited access to health care | a. “The issue is that they are not getting treatment because for someone who works….or seeks that service, you need … to miss a day … and get to a doctor. You may end up not even seeing a doctor … you get frustrated.” (Male leader, Church 3) |

| IV. Knowledge of CVD | |

| 4.1. CVD is major problem in Ghana. | a. “I think it is a major problem….cardiovascular challenge is a serious issue….We have people as young as 22 to 25 years who are diagnosed with high blood pressure and diabetes… It’s a serious issue…” (Male health committee member, Church 3) |

| b. “Yes it is a problem in Ghana; my church is also in Ghana. I think everybody is at risk.” (Male leader, Church 1) | |

| c. “…when talking about cardiovascular diseases it is more dangerous, anybody can go at any time.” (Male leader, Church 2) | |

| 4.2. Stress is a risk factor for CVD. | a. “People get stressed out because they go all the way to church…like the pastor, who lives so far away. He has to drive in the night, he’s praying for this one, there is not even time for them to rest. So rest is a factor. Rest is a major factor…” (Female leader, Church 4) |

| b. “There is not enough for them to eat. They are always worried whether their next meal will come where they are living so all those things are factors.” (Female health committee member, Church 4) | |

| c. “Marriage today is so stressful, so so so stressful.” (Female health committee member, Church 5) | |

| d. “I consider females (overlap of gender and stress) to be the dominant group because of the way they assume things from their emotions.” (Male health committee member, Church 2) | |

| 4.3. Diet is a risk factor for CVD. | a. “We are going back to eat o broni (“white man”) food. We are eating what has been imported – fish which was canned ten years ago (laughter) and then brought here.” (Female leader, Church 4) |

| b. “I feel also that there is too much chemicals in the planting – the fertilizer for the crops. One time I decided to live on vegetable. ...so one day I buy carrots to use for three weeks. The third day the whole thing got rotten and so I became afraid and stopped…if the chemical is too much what effects will it have on my body?” (Female leader, Church 4) | |

| c. “We are so much eating starchy food, and because of that it is causing so many cardiovascular challenges to the body.” (Male health committee member, Church 3) | |

| d. “Early to work, straight and eat very late…” (Male health committee member, Church 5) | |

| e. “Fasting during the day and eating at night.” | |

| 4.4. Age is a risk factor for CVD. | a. “especially people who are 40. We have people very young, as young as 22 to 25 years, who are diagnosed with hypertension, diabetic, you know.” (Male health committee member, Church 3) |

| b. “Once we took blood pressure for the old people like me, but now at 20, 23, or 25, they have that condition.” (Male leader, Church 1) | |

| 4.5. Lack of physical activity is a risk factor for CVD. | a. “One thing I want to say is… we don’t do a lot of exercises – and that’s one major problem with the Ghanaians. If we adopt that attitude of exercise…” (Male leader, Church 5) |

| b. “People in the city cannot walk 15 to 30 metres…they take the tro tro (public transportation).” (Male health committee member, Church 3) |

CHW, community health worker.

Note: Church 1, Charismatic; Church 2, Presbyterian; Church 3, Baptist; Church 4, Presbyterian; Church 5, Pentecostal.

Capacity

All church leaders and health committee members believed that churches should promote health through health education (theme 1.1), health screening (theme 1.2) and health-related activities (theme 1.3). They were unanimous in their belief that their churches had a duty to address the spiritual and physical needs of their members and could effectively educate their congregations about lifestyle practices for promoting cardiovascular health (theme 1.1). They also saw a vital link between conducting health screening and improving church members’ health. Three of five churches were already providing screening tests for hepatitis B as well as eye examinations and blood pressure monitoring (theme 1.2). In addition to health education and screening, church leaders and health committees felt that the church should conduct activities for promoting healthy lifestyles and reducing stress (i.e. exercise programmes or counselling) (theme 1.3).

Regarding the churches’ experiences in health programme delivery, all churches were already providing certain health-related services, such as education about malaria and hepatitis B, hypertension and breast cancer screening. Although these services were primarily intended for the congregation, they were also accessible to non-church-members (theme 1.4). The churches had been offering them for at least 1 year (range: 1–10; mean: 4.25; SD: 4.03) and with a frequency ranging from one to four times per year through collaborations with health professionals or medical suppliers and external organizations (e.g. Korle Bu Hospital, pharmaceutical companies, eyeglass suppliers) (theme 1.5). The support received from organizations was in the form of in-kind donations. This allowed the churches to leverage services without a large outlay of money.

In selecting what health programmes and activities to organize, the churches were influenced by several factors (theme 1.6), the main one being what their congregations felt they needed and wanted to know more about. They issued health alerts and gave talks on specific illnesses, particularly those covered by the media (e.g. pandemic H1N1). Health committees met to prioritize and plan the health programmes, which they then presented to church leaders for approval.

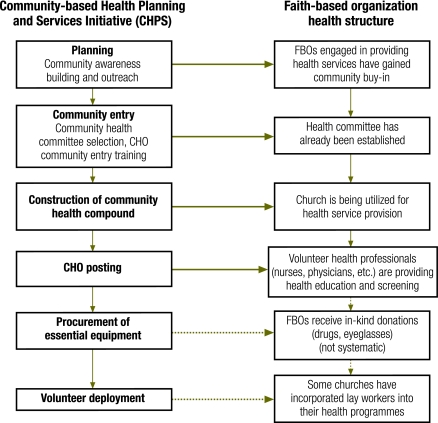

Feasibility

We explored if any church members were CHWs and tried to determine if the CHW model could be applied to the existing church health system. Through the survey we found that the individuals who belonged to the churches’ health committees were primarily non-health professionals from diverse backgrounds (i.e. 17% health professionals, 25% teachers, 25% business/accountants, 33% other professionals). Thus, the CHW model was not entirely new to the churches. Similarly, two supporting themes emerged from the qualitative data. First, although the churches’ health programmes were conducted by health professionals recruited by the churches’ health committee, several lay individuals had been tapped to administer the programmes (theme 2.1). These lay individuals had been trained by the health professionals and were thus able to measure blood pressure, enter data, organize participants and perform other similar tasks. Additionally, faith-based organizations’ existing health service structure had much in common with that of the national CHPS programme (theme 2.2). Four of the six steps involved in implementing the CHPS initiative11 had already been taken (Fig. 1). The role of the health professionals in the churches was similar to that of community health officers and the churches were functioning as community health compounds that provided spaces for health service delivery.

Fig. 1.

Comparison between the Community-based Health Planning and Services model and faith-based organization (FBO) models for cardiovascular disease prevention, Accra, Ghana

CHO, community health officer.

Potential barriers

Four themes emerged in connection with potential challenges to implementing a CHW-run CVD prevention programme in a faith-based organization. One was the shortage of human and financial resources (theme 3.1). All the churches’ health programmes were funded through members’ contributions or national churches. The lack of resources had constrained the recruitment and training of CHWs, the number of people churches could serve and the variety of health services the churches could provide.

Another challenge was the absence of systematic programme monitoring and evaluation (theme 3.2). None of the churches had formally evaluated their programme’s effectiveness, although some informal mechanisms had been established (e.g. member feedback). Although church leaders/health committee members unanimously stated that knowledge was crucial to achieving better health, none had investigated whether the services they provided had, in fact, changed their members’ beliefs, perceptions or health-related behaviours.

While increasing knowledge about health was perceived as essential, poverty was seen as the biggest barrier to applying the knowledge acquired (theme 3.3). Individuals can be aware of what they need to do to stay healthy and yet be unable to afford to make the necessary changes (i.e. eat nutritious meals, have regular health check-ups).

The limited number of adequate health services was also deemed a major challenge (theme 3.4). None of the churches had links to local primary-health-care clinics. Although churches conducted health screenings, they often found it difficult to find suitable referral sources for treatment and continuing care. For many church members, getting to the hospital could generate significant hardship because it often required them to miss a day of work without the certainty that they would get to see a doctor.

Church members’ knowledge

Five themes emerged from the analyses of the qualitative data with respect to knowledge about CVD. Church leaders and health committee members were aware that CVD, specifically diabetes and hypertension, was a major cause of morbidity and mortality in their congregations and in Ghana overall (theme 4.1). They identified stress (theme 4.2), an unhealthy diet (theme 4.3), advanced age (theme 4.4) and lack of physical activity (theme 4.5) as risk factors for developing CVD. Many life stressors (e.g. not having the means to properly nourish oneself, marital conflicts, lack of rest) were seen as major factors contributing to the development of CVD. Diets rich in fats and carbohydrates or both and the “westernization” of the Ghanaian diet were also seen as contributors. While most church leaders and health committee members identified being over 40 as another risk factor for developing CVD, they also expressed concern that an increasing number of people in their early 20s were being diagnosed with hypertension or diabetes. Respondents also felt that easier access to motorized transportation resulted in less physical activity.

Similarly, congregants and health committee members were found to know a lot about CVD. Around 90% of congregants were aware of the risks posed by stress, lack of physical activity and smoking, and of the importance of monitoring blood pressure and diabetes control, yet only slightly more than 50% were aware of the risks of eating fatty foods and red meat, of the importance of taking blood pressure medication and of the need for regular blood pressure monitoring even in the absence of symptoms (Table 2). The patterns were also similar across subgroups (i.e. health committee versus church member, male versus female, people with versus without a history of CVD) (P > 0.05 in all t-tests). Although only two health committee members had worked as CHWs, they scored much better on the knowledge survey (mean score: 83.33; SD: 18.33) than other health committee members.

Table 2. Knowledge about cardiovascular disease (CVD) among congregants and health committee members in churches in Accra, Ghana, 2010.

| Knowledge area | Correct responses (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Congregants (n = 167) | Health committee members (n = 12) | |

| CVD risks | ||

| 1.Heart disease can be prevented | 96 | 91 |

| 2. Cigarette smoking can cause heart disease and stroke | 97 | 100 |

| 3. There is greater risk for heart disease in the elderly | 75 | 73 |

| 4. People with high blood pressure should avoid salt in their diets | 77 | 82 |

| 5. If people quit smoking the risk of heart disease is reduced | 91 | 100 |

| 6. Salty food causes high blood pressure | 77 | 91 |

| 7. High blood pressure is a risk factor for heart disease | 83 | 82 |

| 8. Fatty foods do not increase blood cholesterol levels | 52 | 90 |

| 9. Eating more than 3 meals containing red meat per week is not good for your health | 64 | 27 |

| 10. Eating fruits and vegetables every day is beneficial | 98 | 100 |

| 11. Overweight people are more likely to have heart disease | 77 | 82 |

| 12. Regular exercise reduces the risk of heart disease | 96 | 100 |

| 13. Regular walking can reduce the risk of heart disease | 94 | 100 |

| 14. Stress and sadness increase the risk of heart disease | 88 | 91 |

| 15. Under stressful situations, blood pressure will increase | 91 | 82 |

| 18. Heavy alcohol use does not affect blood pressure | 61 | 82 |

| 19. High cholesterol is a risk factor for heart disease | 86 | 91 |

| 21. Diabetes is a risk factor for heart disease | 67 | 64 |

| 23. Heart disease in your family will increase your risk of heart disease | 50 | 55 |

| CVD symptoms | ||

| 24. Shortness of breath may be a sign of heart disease | 70 | 73 |

| 25. Feeling chest pain or discomfort can be a sign of heart disease | 63 | 55 |

| CVD prevention, control and treatment | ||

| 16. Controlling blood pressure reduces the risk of heart disease | 89 | 100 |

| 17. People with high blood pressure need to use blood pressure medicine for life | 54 | 46 |

| 20. People with high cholesterol despite diet and exercise need to take medication | 60 | 46 |

| 22. People with diabetes need to control their blood sugar | 95 | 91 |

| 26. People should only get their blood pressure checked if they have chest pain or headaches | 50 | 46 |

| 27. If you have high blood pressure taking a medicine for 1 month can cure you | 52 | 55 |

| Knowledge score, mean and SD | 76.09 (13.68) | 77.39 (14.06) |

SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

This study investigated the feasibility of having CHWs implement a CVD prevention programme in faith-based organizations. This is the first study that explored Ghanaian churches’ capacity and experience in conducting health programmes, and our results suggest that the CHW model for CVD prevention can be applied in faith-based organizations. Leaders from all five churches, irrespective of denomination, saw their own institution as playing a significant role in promoting and maintaining the health of Ghanaians. In addition, we found the existing health service structure of faith-based organizations to be consistent with the basic structure of the nationwide CHPS.24

Applying the CHW model to CVD prevention programmes within faith-based organizations in Accra has several advantages:

Service planning. Churches possess the physical space within which health services are currently being provided, making it unnecessary to construct a new health compound. Furthermore, they are already viewed as crucial and beneficial to their communities.

Service accessibility. Churches are accessible and keen to offer their health programmes to non-congregants as well as church members.

Programme acceptability. Having CHWs from faith-based organizations administer CVD prevention programmes has two advantages: (i) these church-affiliated professionals are already accepted and respected within their religious communities; and (ii) when CHWs provide services in the same place where they receive spiritual sustenance, their commitment to the organization is strengthened and their turnover could be reduced.

Cost. Many churches providing health services received assistance through partnerships with outside individuals and organizations. These partnerships could help streamline the procurement process, keeping costs low. In addition, using lay workers contains the cost of services.

The faith-based organization approach to CVD prevention could substantially benefit the greater Accra area, where the CHPS model has penetrated least. There is a wide gap between CHPS planning and service delivery that has been attributed to concerns about funding and operational complexity.11 Partnering with faith-based organizations can provide the innovation necessary to extend the successful CHPS initiative to Accra.

Implementing a CVD prevention programme run by CHWs in a faith-based organizations poses several challenges. Poverty, limited financial and human resources, the absence of systematic programme monitoring and evaluation and the lack of strategic linkages for continuing care are all potential barriers to implementation. Although the churches already engage lay workers for health activities to some extent, further systematization of recruitment, training, supervision and quality control is vital.

A major limitation of this exploratory study is the sample. Although the churches that participated in this study represent the various types of Christian churches existing in Accra, they do not represent the entire range of Christian churches2 in urban and rural Ghana. The 2008 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey report classified the Christian churches in Ghana as Anglican, Catholic, Methodist, Pentecostal/Charismatic, Presbyterian and “other” (e.g. Baptist, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Mormons).25 The study did not cover Moslem or traditional/spiritualist organizations, and the findings may have been different if these other types of faith-based organizations had been included. Finally, self-selection bias is a possibility since the faith-based organizations that agreed to participate in the study were probably already interested in improving the health status of their congregants.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest a direction for developing CHW-run CVD prevention programmes in Ghana. An important next step for policy planning would be to further investigate the nature of the partnerships that could be established between the faith-based organizations, the Ministry of Health, the Christian Health Association of Ghana and the Ghana Pentecostal Council (which links and oversees the work of the Pentecostal and Charismatic Churches) to carry out CVD prevention. In addition, the gaps in CVD knowledge that were identified in the survey should be explored further during future programme development.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank church leaders, church health committee members and congregants in Accra, as well as Fidelia Dake and Marian Bannerman – graduate students at the Regional Institute for Population Studies of the University of Ghana – who provided technical assistance and facilitated their access to churches.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Addo J, Smeeth L, Leon DA. Hypertension in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review. Hypertension. 2007;50:1012–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.093336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.BeLue R, Okoror TA, Iwelunmor J, Taylor KD, Degboe AN, Agyemang C.et alAn overview of cardiovascular risk factor burden in sub-Saharan African countries: a socio-cultural perspective. Global Health 2009510. 10.1186/1744-8603-5-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vedanthan R, Fuster V. Cardiovascular disease in Sub-Saharan Africa: a complex picture demanding a multifaceted response. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:516–7. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The world health report: reducing risks, promoting healthy life Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2002/en/whr02_en.pdf [accessed 10 June 2011].

- 5.de-Graft Aikins A. Ghana’s neglected chronic disease epidemic: a developmental challenge. Ghana Med J. 2007;41:154–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadiri S. Tackling cardiovascular disease in Africa. BMJ. 2005;331:711–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seedat YK. Impact of poverty on hypertension and cardiovascular disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2007;18:316–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10:282–98. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Community-Based Health Planning and Services [Internet]. Accra: CHPS; 2009. Available from: http://ghanachps.org/?page_id=7 [accessed 10 June 2011].

- 10.Nyonator FK, Awoonor-Williams JK, Philips JF, Jones TC, Miller RA. The Ghana Community-Based Health Planning and Services initiative: fostering evidence-based organizational change and development in a resource-constrained setting New York: Population Council; 2003. Available from: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/wp/180.pdf [accessed 10 June 2011]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nyonator FK, Awoonor-Williams JK, Phillips JF, Jones TC, Miller RA. The Ghana community-based health planning and services initiative for scaling up service delivery innovation. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20:25–34. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czi003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, Berry J. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1030–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.6.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chikwendu E. Faith-based organizations in anti-HIV/AIDS work among African youth and women. Dialect Anthropol. 2004;28:307–27. doi: 10.1007/s10624-004-3589-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bopp M, Wilcox S, Laken M, Hooker SP, Parra-Medina D, Saunders R, et al. 8 Steps to Fitness: a faith-based, behavior change physical activity intervention for African Americans. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6:568–77. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.5.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otolok-Tanga E, Atuyambe L, Murphy CK, Ringheim KE, Woldehanna S. Examining the actions of faith-based organizations and their influence on HIV/AIDS-related stigma: a case study of Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2007;7:55–60. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2007.7.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agadjanian V, Sen S. Promises and challenges of faith-based AIDS care and support in Mozambique. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:362–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.085662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gatua EW. Country watch: Kenya. AIDS STD Health Promot Exch. 1995;4:9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salm SJ, Falola T. Culture and customs of Ghana Westpoint: Greenwood Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christian Health Association of Ghana. About CHAG [web page]. Available from http://www.chagghana.org/chag/index.php [accessed 30 March 2010].

- 20.Sobo EJ. Culture and meaning in health services research Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padgett DL. Qualitative methods in social work research London: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arikan I, Metintas S, Kalyoncu C, Yildiz Z. The cardiovascular disease risk factors knowledge level (CARRF-KL) scale: a validity and reliability study. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2009;37:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co.; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyonator FK, Akosa AB, Awoonor-Williams JK, Phillips JF, Jones TC. Chapter 5: Scaling up experimental project success with the Community-based Health Planning and Services initiative in Ghana. In: Simmons R, Fajans P, Ghiron L, editors. Scaling up health service delivery and programmes Accra: World Health Organization & ExpandNet; 2007: pp. 89-111. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2008. Calverton: Ghana Statistical Service, Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, ORC Macro;.2009.