Abstract

Tumor cells are commonly aneuploid, a condition contributing to cancer progression and drug resistance. Understanding how chromatids are linked and separated at the appropriate time will help uncover the basis of aneuploidy and will shed light on the behavior of tumor cells. Cohesion of sister chromatids is maintained by the multi-protein complex cohesin, consisting of Smc1, Smc3, Scc1 and Scc3. Sororin associates with the cohesin complex and regulates the segregation of sister chromatids. Sororin is phosphorylated in mitosis; however, the role of this modification is unclear. Here we show that mutation of potential cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) phosphorylation sites leaves sororin stranded on chromosomes and bound to cohesin throughout mitosis. Sororin can be precipitated from cell lysates with DNA–cellulose, and only the hypophosphorylated form of sororin shows this association. These results suggest that phosphorylation of sororin causes its release from chromatin in mitosis. Also, the hypophosphorylated form of sororin increases cohesion between sister chromatids, suggesting that phosphorylation of sororin by Cdk1 influences sister chromatid cohesion. Finally, phosphorylation-deficient sororin can alleviate the mitotic block that occurs upon knockdown of endogenous sororin. This mitotic block is abolished by ZM447439, an Aurora kinase inhibitor, suggesting that prematurely separated sister chromatids activate the spindle assembly checkpoint through an Aurora kinase-dependent pathway.

Key words: Cell cycle, Cohesion, Sister chromatids, Spindle assembly checkpoint, Aneuploid

Introduction

Cell cycle control mechanisms are altered in cancer cells, often leading to chromosomal instability and alterations in chromosome number. Several processes normally ensure that chromosomes are segregated with high fidelity. For example, the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), allows anaphase entry only after all chromosomes acquire a bipolar attachment to the spindle (Maresca and Salmon, 2010). Equal chromosome segregation to daughter cells also strictly depends upon cohesion between sister chromatids, allowing them to travel together and migrate to the cell equator upon bipolar attachment to the spindle. The timing of dissolution of cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition is essential to ensure that chromosome segregation is temporally coupled to mitotic exit and spatially coupled to cytokinesis (Michaelis et al., 1997).

Cohesion of the sister chromatids is maintained in part by a four-subunit complex, which consists of structural maintenance of chromosomes 1 and 3 (Smc1, Smc3), the kleisin family protein sister chromatid cohesin (Scc1) and the accessory subunit Scc3 (Haering et al., 2002; Michaelis et al., 1997). Pds5 and Wap1 are weakly associated with the cohesin complex and regulate the interaction of cohesin with chromatin (Panizza et al., 2000; Shintomi and Hirano, 2009). Smc1 and Smc3 have ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-like ATPases at one end of an extended coiled coil. At the other end are the hinge domains that interact to create V-shaped Smc1–Smc3 heterodimers (Haering et al., 2002). Scc1 binds to the Smc3 and Smc1 ATPase heads, creating a tripartite ring that is 45 nm in diameter (Onn et al., 2008). Cohesin is thought to associate with chromosomes by trapping DNA within a monomeric ring (Haering et al., 2008). In vertebrates, cohesin binds to DNA in telophase and continues to bind until anaphase (Guacci et al., 1997; Sumara et al., 2000). Cohesin-bound chromatin is found in two states: noncohesive and cohesive. Because cohesin associates with chromatin before DNA replication, cohesin first binds to chromatin in a noncohesive state.

During prophase and prometaphase, the majority of cohesin dissociates from the chromosome arms in a process referred to as the prophase pathway (Waizenegger et al., 2000). Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) phosphorylates an isoform of Scc3 (SA1 or SA2), causing release of cohesion from the arms (Hauf et al., 2005; Sumara et al., 2002). Interestingly, some cohesin along the arms is protected by shugoshin 1 (Sgo1) and is cleaved by separase (Nakajima et al., 2007; Shintomi and Hirano, 2009). The Sgo1–protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) complex protects centromeric cohesin by counteracting Plk1 until the kinetochores are captured by the spindle microtubules (Kitajima et al., 2006). At the metaphase–anaphase transition, the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) causes the degradation of securin, releasing separase. Plk1 phosphorylates Scc1 to facilitate its cleavage by separase, which leads to the dissolution of cohesion (Onn et al., 2008; Sumara et al., 2002).

Sororin was originally identified using a small pool expression screen for proteins degraded by the APC/C in Xenopus laevis extracts (Rankin et al., 2005). Suppression of sororin with small interfering RNAs causes loss of sister chromatid cohesin, implicating sororin in the maintenance of cohesion (Diaz-Martinez et al., 2007; Rankin et al., 2005; Schmitz et al., 2007). In fact, sororin is recruited to the cohesin complex during S phase as a result of concurrent acetylation of SMC protein by Eco2 (Lafont et al., 2010; Nishiyama et al., 2010). Once at the cohesin complex, sororin displaces Wapl from Pds5 (Nishiyama et al., 2010). Because Wapl is a cohesion destabilizer, the recruitment of sororin to DNA during S phase helps to solidify sister chromatid cohesion until mitosis. It is not clear how this stabilizing effect is overcome during prophase to allow removal of cohesin from chromosome arms. Here we demonstrate that sororin is phosphorylated in response to cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) in vitro and in vivo. Interestingly, mutation of potential Cdk1 phosphorylation sites in sororin creates a protein that is unable to dissociate from chromosomes in mitosis. Furthermore, overexpression of phosphorylation-deficient sororin increases cohesion yet is still able to rescue a mitotic arrest triggered by knockdown of the endogenous protein. These observations suggest that phosphorylation of sororin by Cdk1 inhibits the ability of sororin to stabilize cohesion upon entry into mitosis.

Results

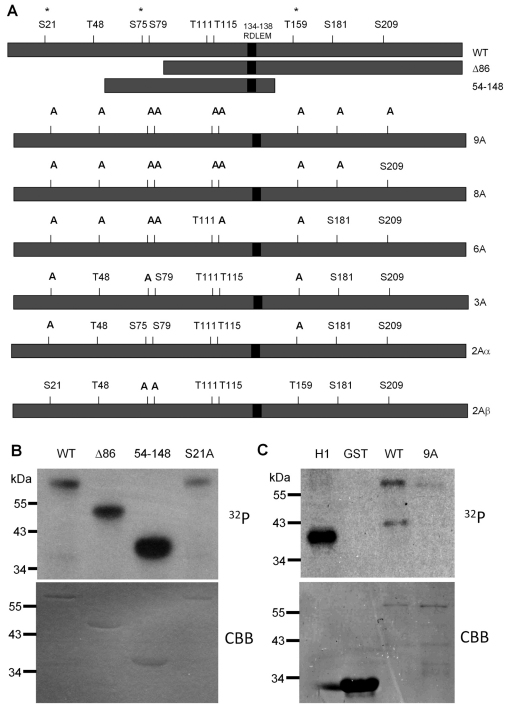

Cdk1 phosphorylates sororin

Sororin extracted during mitosis exhibits a slower electrophoretic mobility as a result of phosphorylation (Rankin et al., 2005). We investigated the role of Cdk1, a kinase that is highly active in mitosis, in this phosphorylation event. Two truncated forms of sororin were fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) and used for in vitro kinase reactions. We identified a potential cyclin interaction motif (CIM) in the sororin sequence and retained it in our truncated forms of the protein. In other Cdk substrates, cyclin binds to the CIM and recruits Cdk allowing more efficient phosphorylation. Full-length, as well as both truncated forms of sororin were phosphorylated by recombinant Cdk–cyclin B1 in vitro (Fig. 1A,B). The full consensus for Cdk1 phosphorylation is [S/T]Px[K/R], although some substrates simply contain a serine or threonine followed by proline (Ubersax et al., 2003). Sororin contains three sites that conform to the full consensus and six others that are serines or threonines followed by prolines (Fig. 1A). Mutation of one of the full-consensus sites (S21) to alanine had no effect on phosphorylation. Phosphoproteomic mapping data indicate that all nine of the potential Cdk1 sites could be phosphorylated in vivo (Beausoleil et al., 2006; Cantin et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2009; Dephoure et al., 2008; Gnad et al., 2007; Olsen et al., 2006; Van Hoof et al., 2009). Therefore, we mutated all nine serines/threonines followed by prolines to alanines to further investigate the role of phosphorylation in sororin function. (Throughout this paper, superscripts are used to indicate which form of sororin is used, for example sororinWT for wild-type sororin and sororin9A for the mutant in which all nine serines or threonines followed by proline were mutated to alanine.) As expected, GST–sororin9A was poorly phosphorylated by Cdk1–cyclin B1 in vitro (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Cdk1 phosphorylates sororin. (A) Diagram of wild-type and mutant forms of sororin used in this study. Nine potential sites of phosphorylation by Cdk1 are indicated above the wild-type sororin. Each one of these sites appears to be phosphorylated in vivo, as determined by proteomic analysis of phosphopeptides isolated from cells (information obtained from phosida and phosphosite websites) (Beausoleil et al., 2006; Cantin et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2009; Dephoure et al., 2008; Gnad et al., 2007; Olsen et al., 2006; Van Hoof et al., 2009). Each of these nine sites has a serine or threonine followed by proline (minimal Cdk consensus), whereas sites marked with an asterisk conform to the full Cdk consensus ([S/T]Px[K/R]). RDLEM is the potential CIM. Below the wild-type sororin are the various truncation and multi-site mutants of sororin that were generated. In addition, a single mutant at each of the nine sites was generated (not shown). (B) Phosphorylation of sororin by Cdk1 in vitro. Recombinant Cdk1–cyclin B1 was mixed with GST–sororin and a phosphorylation reaction was carried out in vitro with [32P]ATP. Reactions were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography. (C) Effect of serine to alanine mutations on sororin phosphorylation. Recombinant sororinWT or sororin9A with an N-terminal GST tag was phosphorylated in an in vitro reaction with Cdk1–cyclin B1 and [32P]ATP. Reactions were analyzed by autoradiography with histone H1 serving as a positive control. CBB, Coomassie-Brilliant-Blue-stained gels.

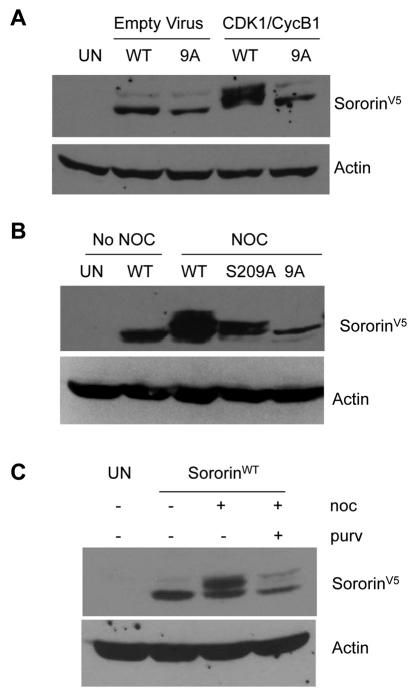

To analyze sororin phosphorylation in vivo, we added a V5 tag to the C-terminus of the sororin mutants shown in Fig. 1A and used recombinant adenoviruses to overexpress a nuclear targeted cyclin B1 (NB1) and a constitutively active mutant Cdk1-AF (Cdk1 T14A Y15F) (Jin et al., 1998). HeLa M cells were blocked in S phase with hydroxyurea and then infected with adenovirus to express NB1 and Cdk1-AF. Western blotting showed that overexpression of Cdk1–cyclin B1 reduced the mobility of sororinWT–V5 but not sororin9A–V5 (Fig. 2A). This result suggests that sororin is phosphorylated in response to Cdk1–cyclin B1. Next, we tested the effect of mutating potential phosphorylation sites on the mobility of sororin during mitosis. HeLa M cells were transfected with sororin cDNAs and treated with nocodazole to block the cells in mitosis. SororinWT–V5 migrated as a doublet, whereas sororin9A–V5 failed to exhibit a mobility shift (Fig. 2B). We also mutated each of the nine Cdk1 sites to alanine, individually as well as in various combinations (Fig. 1A). Every single and multiple mutant (excluding sororin9A–V5) showed a mobility shift (supplementary material Fig. S1A,B). Thus, phosphorylation of a number of sites appears to be responsible for reducing the electrophoretic mobility of sororin from cells in mitosis.

Fig. 2.

Electrophoretic mobility of sororin. HeLa M cells were transiently transfected with sororinWT–V5 or mutant forms of sororin and analyzed by western blot to detect a mobility shift. (A) Overexpression of Cdk1–cyclin induces a sororin mobility shift. HeLa M cells were blocked in S phase with hydroxyurea and infected with recombinant adenovirus that expressed Cdk1 T14A Y15F (Cdk1-AF) and cyclin B1 fused to the nuclear targeting signal of SV40 T antigen (NB1). Cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting with an antibody to the V5 tag on sororin. (B) Effect of mutations on the electrophoretic migration of sororin. HeLa M cells were transiently transfected with sororin–V5 constructs expressing the indicated proteins. Transfected cells were either left untreated or treated with nocodazole (noc) for 20 hours to block them in mitosis. Cell lysates were separated on a 12.6% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by western blotting with an antibody to the V5 tag. (C) Effect of purvalanol A (purv) on the phosphorylation of sororin. Purvalanol A inhibits phosphorylation of sororin. HeLa M cells were transiently transfected with sororinWT-V5, treated with nocodazole with and without purvalanol A for 16 hours, and analyzed by western blotting.

To further investigate the notion that Cdk1 is the kinase that phosphorylates sororin, inhibitor studies were performed. HeLa M cells were transfected with sororinWT–V5 and treated with nocodazole in the presence or absence of purvalanol A to inhibit Cdk1. Extracts from cells treated with nocodazole exhibited a mobility shift compared with untreated cells (Fig. 2C). Cells treated with both nocodazole and purvalanol A contained less of the slower migrating species (Fig. 2C). These results produce further evidence that Cdk1–cyclin B1 is responsible for the phosphorylation of sororin in vivo.

Phosphorylation-deficient sororin fails to be released from chromatin during mitosis

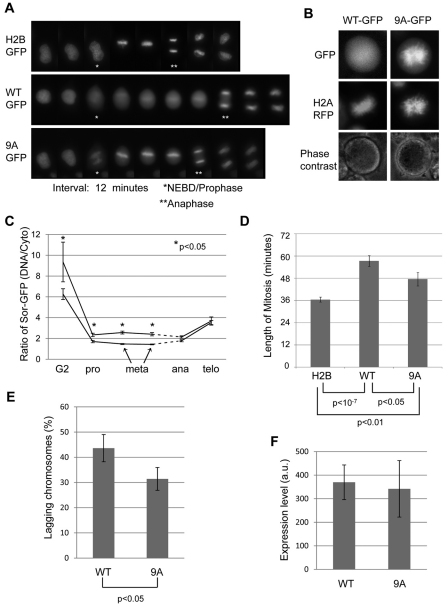

To better understand the importance of phosphorylation, we fused a GFP tag to the C-terminus of wild-type and mutant sororin. GFP-tagged sororinWT and sororin9A were first compared by transfecting the constructs into HeLa M cells and performing live-cell imaging. As previously observed, sororinWT–GFP was displaced from the chromatin and localized to the cytoplasm in prometaphase but relocalized to the chromatin in anaphase (Rankin et al., 2005). By contrast, sororin9A–GFP remained localized to the chromatin throughout mitosis (Fig. 3A). Continued imaging revealed that the intensity of both wild-type and 9A sororin–GFP was rapidly reduced after telophase, consistent with recognition by the APC/C (supplementary material Fig. S2) (Rankin et al., 2005). In order to confirm that sororin9A–GFP colocalizes with chromatin in mitosis, we co-transfected HeLa M cells with sororin–GFP and histone H2A–RFP. Sororin9A–GFP, but not sororinWT–GFP, colocalized with H2A–RFP in prometaphase, suggesting that mitotic phosphorylation of sororin is necessary to remove the protein from the chromatin (Fig. 3B). To quantify staining patterns, we determined the ratio of sororinGFP on the chromatin to that in the cytoplasm. Sororin9A–GFP was significantly more enriched on chromatin than sororinWT–GFP from G2 through metaphase, whereas at anaphase similar staining was observed for both sororinWT–GFP and sororin9A–GFP (Fig. 3C). For both forms of sororin, we observed a large drop in chromatin enrichment as cells entered prophase, consistent with the release of sororin into the cytoplasm at nuclear envelope breakdown (Fig. 3C). This observation also indicates that a proportion of sororin9A–GFP is released from chromatin at the onset of mitosis.

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylation of sororin releases it from chromatin during mitosis. (A) Localization of sororin–GFP during mitosis. H2B–GFP, sororinWT–GFP and sororin9A–GFP were transiently transfected into HeLa M cells. Time-lapse images of cells progressing through mitosis as seen by fluorescence microscopy (image interval: 12 minutes). Entry into mitosis was indicated by release of sororin–GFP from the nucleus (nuclear envelope breakdown; NEBD). The end of mitosis was indicated by anaphase separation of chromatids. As a control, cells were transiently transfected with H2B–GFP to visualize DNA. In this case, entry into mitosis was taken as the first frame in which DNA condensation was visible. (B) Sororin9A–GFP localizes to DNA in mitosis. Histone H2A–RFP and sororin9A–GFP were transiently transfected into HeLa M cells. An example of a cell showing colocalization of sororin9A–GFP and H2A–RFP is shown. (C) Enrichment of sororinGFP on chromatin. Frames from time-lapse microscopy were used to quantify mean pixel intensities in a defined region of the chromatin and compared with cytoplasmic intensity of the same-sized region. Because cells spent different amounts of time in metaphase, only the first two metaphase frames were quantified. Also, the onset of anaphase occurred at a different time for each cell; this effect is indicated by the dashed line. Averages of at least eight cells with standard errors are shown. (D) SororinWT–V5 and sororin9A–V5 increase the length of mitosis. HeLa M cells were transiently transfected with either sororinWT–GFP or sororin9A–GFP. Frames from time-lapse microscopy were used to quantify the length of mitosis for each cell. (E) Quantification of lagging chromosomes. HeLa M cells were transfected with either sororinWT–V5 or sororin9A–V5, fixed and analyzed by immunofluorescence with antibodies to the V5 tag and to H2A phosphorylated at T121 to indicate centromeres. V5-positive cells in metaphase were assessed for the presence of chromosomes that had not aligned at the metaphase plate. Values are average percentages of cells with lagging chromosomes; bars indicate ± s.e.m. (F) Average expression level of either sororinWT–GFP or sororin9A–GFP in live cells. HeLa M cells were transfected with GFP-tagged sororin and visualized by time-lapse fluorescence microscopy as in A. Single frames of GFP-positive cells in metaphase were used to measure average pixel intensities within the whole cell (a.u., arbitrary units). Values are average from at least 28 cells for each condition; bars indicate ± s.e.m.

Overexpression of sororinWT–GFP in HeLa M cells increased the duration of mitosis when compared with cells transfected with H2B–GFP alone (Fig. 3D). Sororin9A–GFP also increased the duration of mitosis, but not quite as efficiently as sororinWT–GFP. In addition we observed a subtle but significant increase in the percentage of cells with lagging chromosomes after overexpression of sororinWT compared with sororin9A (Fig. 3E, supplementary material Fig. S3A). The average pixel intensities of sororinWT–GFP and sororin9A–GFP in the live-cell image series were similar (Fig. 3F). Therefore, the increase in lagging chromosomes, and not expression level, could be responsible for the increased mitotic duration in cells overexpressing sororinWT. We considered the possibility that overexpression of sororin might alter the ratio of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated endogenous sororin, thereby altering chromosome dynamics and lengthening mitosis. After transfecting HeLa M cells with sororin and treating cells with nocodazole, immunoblotting was performed. There was no apparent difference in the ratio of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated sororin when it was overexpressed (supplementary material Fig. S1C).

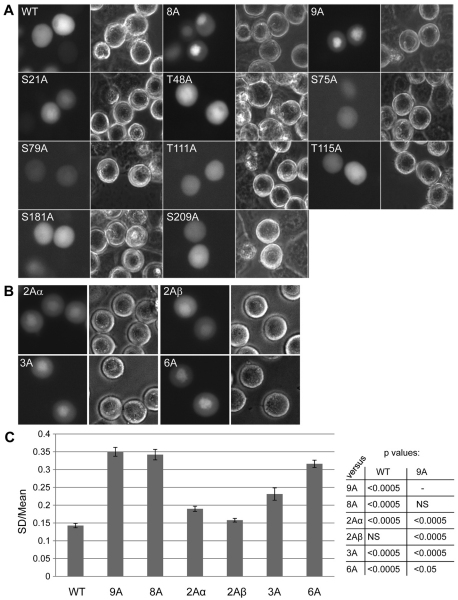

Multiple sites of phosphorylation contribute to chromatin release of sororin

In order to identify the phosphorylation sites required for the removal of sororin from chromosomes, HeLa M cells were transiently transfected with a number of single and multiple point mutants. Cells were then treated with nocodazole and the localization of the sororin–GFP fusions was determined in live cells. Sororin8A–GFP and sororin9A–GFP both localized to the chromatin (Fig. 4A; sororin8A is identical to sororin9A except that S209 is wild type). Similar results were obtained when we created N-terminal GFP constructs of sororinWT and sororin9A, suggesting that this effect is not due to the C-terminal tag (Dreier and Taylor, unpublished data). Fixed cells expressing V5- or GFP-tagged sororin9A showed only minimal colocalization of sororin with chromatin. Therefore, analysis of subcellular localization was carried out using C-terminal GFP tags in live cells. All the single point mutants localized to the cytoplasm in mitotic cells (Fig. 4A). Cells transfected with additional multi-site mutants of sororin showed intermediate patterns of localization between sororinWT–GFP and sororin9A–GFP (Fig. 4B). In order to quantify these patterns we captured digital images of live GFP-transfected cells and measured the standard deviation of pixel intensities within the bounds of a cell [cells with uniform sororin staining have lower standard deviations (Huang et al., 2009)]. The standard deviations was then corrected by mean pixel intensity of the same cell and the corrected standard deviation derived from many cells was presented as an average value (Fig. 4C). One of the sororin mutants with two Cdk1 sites mutated (2Aα) showed a slightly higher corrected standard deviations compared with wild-type sororin. Sororin3A–GFP and sororin6A–GFP showed intermediate corrected standard deviations between sororinWT–GFP and sororin9A–GFP (Fig. 4C). We also measured the fold enrichment as described for Fig. 3C, which indicated similar trends of staining with the multiple mutants. Overall, these results suggest that multiple sites of phosphorylation, possibly acting in an additive manner, are required to remove sororin from the chromosomes.

Fig. 4.

Multiple sites of phosphorylation contribute to the release of sororin from chromatin during prometaphase. SororinWT–GFP and mutant forms of sororin were transiently transfected into HeLa M cells. Transfected cells were exposed to nocodazole to block them in prometaphase. (A) Localization of single point mutants of sororin. Representative cells transfected with the indicated single point mutants of sororin are shown. SororinT159A–GFP showed undetectable levels of fluorescence. (B) Localization of sororin–GFP with multiple S/T to A mutations in HeLa M cells. Specific mutations in each of the constructs are shown in Fig. 1. (C) Staining uniformity of various forms of sororin. To measure the uniformity of staining, digital images were captured of live transfected cells. The standard deviation (SD) of pixel intensities was then determined for each cell. This value was then corrected for the average pixel intensity of each corresponding cell. This corrected standard deviation was averaged over many cells and is shown with standard errors indicated by bars. The various mutants were compared with either sororinWT or sororin9A using a Student's t-test. P-values are indicated in the table.

Phosphorylation-deficient sororin shows increased association with the cohesin complex

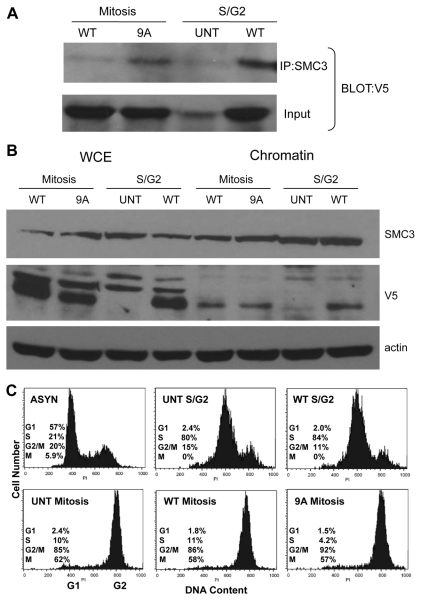

To further investigate the mechanism by which phosphorylation controls the release of sororin from chromosomes, we investigated the interaction between sororin and the cohesin complex. We compared cells progressing through S to G2 phases to those blocked in prometaphase with nocodazole (Fig. 5C). Using coimmunoprecipitation, we observed that in prometaphase, more sororin9A–V5 than sororinWT–V5 was immunoprecipitated with SMC3 (Fig. 5A). In S–G2, more sororinWT–V5 was associated with SMC3 than in prometaphase (Fig. 5A). Sororin did not detectably change SMC3 levels in chromatin (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that sororinWT–V5 is associated with the cohesin complex throughout S phase, but dissociates in prometaphase. The fact that more sororin9A–V5 than sororinWT–V5 is associated with SMC3 in prometaphase suggests that dissociation from the cohesin complex might be triggered by Cdk1-mediated phosphorylation of sororin.

Fig. 5.

Phosphorylation of sororin reduces its association with the cohesin complex. SororinWT or sororin9A, which contained C-terminal V5 epitope tags, were transiently transfected into HeLa M cells. Some samples were untransfected (UNT). The cells were then synchronized in S phase with 2 mM thymidine for 24 hours. Thymidine was removed and nocodazole was added for 14 hours to synchronize the cells in mitosis. To prepare an S–G2 population, cells were released from the thymidine block for 6 hours. Chromatin was prepared as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Sororin9A associates with chromatin in mitosis. Cohesin was immunoprecipitated with an antibody to SMC3. Immune complexes were loaded onto 12.6% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by western blotting with an anti-V5 antibody. (B) Sororin does not alter the levels of SMC3. Samples were prepared as in A and loaded onto 12.6% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by western blotting with SMC3 and anti-V5 antibodies. (C) Verification of the cell cycle stage for each of the cell populations. Flow cytometry was performed using propidium iodide-stained cells. Numbers of cells in G1, S or G2–M were determined from flow cytometry. M, the mitotic index of parallel cultures prepared by the chromosome dropping method; AYSN, asynchronous; UNT, untransfected.

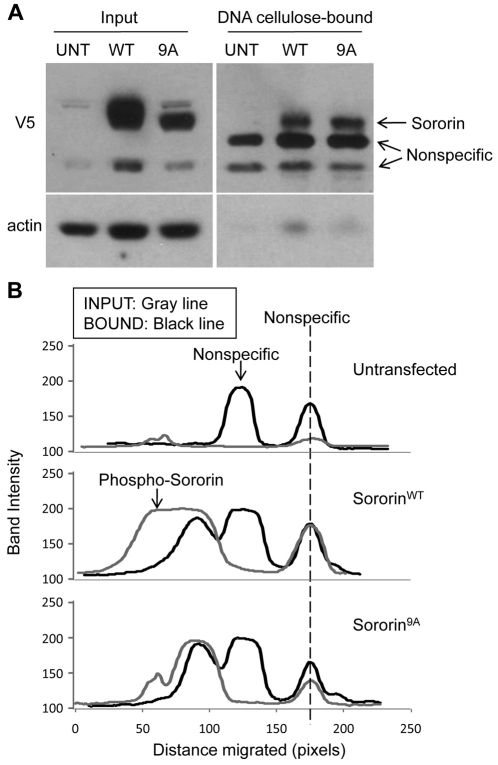

In order to obtain more insight into the association of sororin with chromatin, we tested whether the protein could be precipitated from cell lysates with DNA–cellulose. For those experiments, HeLa M cells were transfected with wild-type or 9A forms of sororin bearing C-terminal V5 tags. Cell lysates were incubated with DNA–cellulose and the bound fractions were analyzed by western blotting. Both sororinWT–V5 and sororin9A–V5 associated with DNA–cellulose (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, only the fast migrating form of sororinWT–V5 was found in the bound fraction, suggesting that phosphorylation reduces the association of sororin with DNA–cellulose (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

The nonphosphorylated form of sororin binds to DNA–cellulose. (A) Association of sororin with DNA–cellulose. HeLa M cells were transiently transfected with either sororinWT–V5 or sororin9A–V5. UNT, untransfected. Cells were blocked in mitosis by exposure to nocodazole for 16 hours. Cell lysates were incubated with DNA–cellulose for 16 hours and the bound fraction was washed extensively. Proteins remaining associated with the DNA–cellulose were analyzed by western blotting. An aliquot of the lysate used for the binding reaction (Input) was also analyzed for comparison. (B) Desitometric scans of the lanes. The fastest migrating nonspecific band was used to register the scans.

Effect of phosphorylation-deficient sororin on sister chromatid cohesion

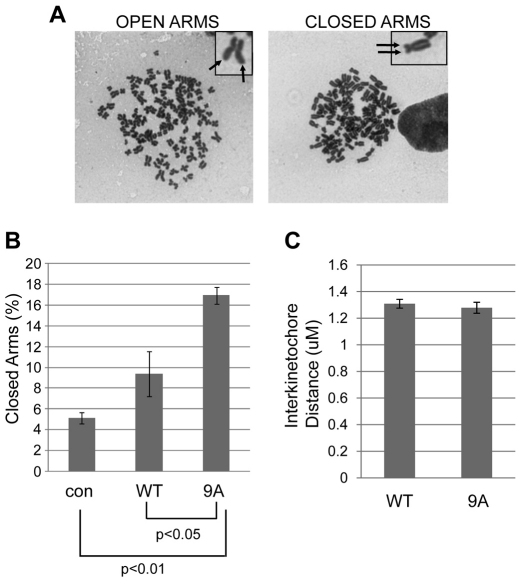

We hypothesized that constitutive binding of sororin9A to chromosomes increases sister chromatid cohesion. To examine sister chromatid cohesion in prometaphase, HeLa M cells were transfected with V5-tagged sororin. Transiently transfected cells were blocked in mitosis with nocodazole, and examined using chromosome spreads. Cells transfected with sororin9A, but not sororinWT showed a significant increase in the number of cells with closed arms (Fig. 7A,B). Chromosome spreads were prepared after hypotonic swelling followed by fixation and drying of chromosomes on glass slides before staining. To test whether cohesion is affected by sororin9A–V5 in intact fixed cells, we measured interkinetochore distances using immunofluorescence (for example see supplementary material Fig. S3B). We observed no significant difference in interkinetochore distances in cells overexpressing sororin9A–V5 compared with sororinWT–V5 (Fig. 7C). Overall, these observations suggest that overexpression of sororin9A–V5 increases sister chromatid cohesion. The fact that sororin9A–V5 did not alter interkinetochore distances might mean that sororin9A–V5 stabilizes the complex during chromosome preparation, but does not directly block the removal of cohesion. Alternatively, sororin might be more important in regulating arm cohesion than pericentromeric cohesion.

Fig. 7.

Sororin9A alters sister chromatid cohesion. (A) Examples of chromosome spreads with closed or open arms. SororinWT–V5 and sororin9A–V5 were transfected into HeLa M cells. The cells were then treated for 24 hours with 2 mM thymidine, after which the thymidine was washed off and 100 ng/ml of nocodazole was added for 24 hours. Then chromosome drops were performed. Images of Giemsa-stained cells are shown. Arrows indicate sister chromatids. (B) Quantification of closed sister chromatids in prometaphase. Cells were prepared as in A, and the percentage of spreads where sister chromatids were closed was assessed. Values are averages ± s.e.m. (C) Measurement of interkinetochore distance. HeLa M cells were transfected with sororinWT–V5 or sororin9A–V5 and analyzed by immunofluorescence using antibodies to Hec1 and H2A phosphorylated at T121 [H2A T121(P)]. Antibodies to the V5 tag were also used to identify cells expressing the transfected sororin proteins. H2A T121(P) staining indicates which Hec1-positive dots belong to sister chromatids (see supplementary material Fig. S3B). At least 10 Hec1 pairs per cell were analyzed and at least 14 cells were measured for each condition. Values are averages ± s.e.m.

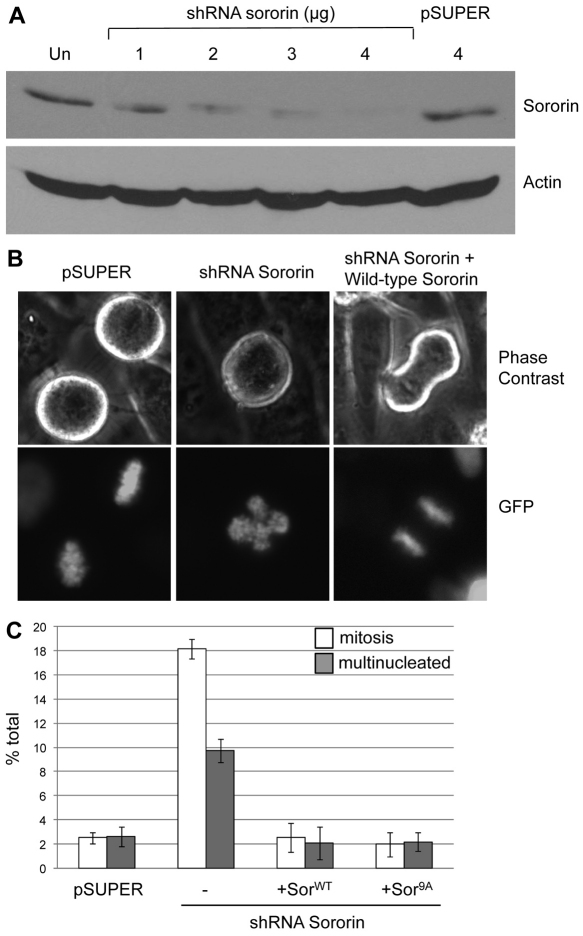

Phosphorylation-deficient sororin rescues mitotic arrest induced by sororin knockdown

To investigate the effect of phosphorylation on the function of sororin, we generated a short hairpin (sh) RNA to the 3′UTR of sororin, allowing us to reconstitute cells with either sororinWT–V5 or sororin9A–V5. Transiently transfecting HeLa M cells with sororin shRNA caused sororin knockdown (Fig. 8A) and resulted in a prometaphase arrest (Fig. 8B,C). Cells blocked in mitosis as a result of sororin knockdown were characterized by misaligned chromosomes that did not form a metaphase plate (Fig. 8B), similar to previous reports (Diaz-Martinez et al., 2007; Schmitz et al., 2007). Reconstituting with either sororinWT–V5 or sororin9A–V5 reduced the percentage of cells in mitosis (Fig. 8C). Also, knocking down sororin increased the percentage of cells with more than one nucleus, presumably as a result of progress through a defective mitosis. SororinWT–V5 and sororin9A–V5 were similarly able to suppress the formation of multinucleated cells when combined with the shRNA against sororin (Fig. 8C). These results suggest that phosphorylation-deficient sororin retains those activities of wild-type sororin required for cells to progress through mitosis.

Fig. 8.

SororinWT–V5 and sororin9A–V5 alleviate a mitotic arrest induced by sororin knockdown. (A) Efficiency of shRNA knockdown of sororin. HeLa M cells were transiently transfected with either a plasmid that produced an shRNA targeting the 3′UTR of sororin (shRNA sororin) or empty pSUPER. Cell lysates were separated on 12.6% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and analyzed by western blotting with an antibody to endogenous sororin. Actin served as a loading control. (B) Defective metaphase plates after sororin knockdown. pSUPER, shRNA sororin or shRNA sororin with sororinWT–V5 were transiently transfected into HeLa M cells. Sororin cDNA clones used in this study lacked a 3′UTR and are not targeted by the shRNA construct. H2B–GFP was also transfected to visualize DNA. Examples of live mitotic cells are shown. (C) Rescue of mitotic arrest by reconstituted sororin. HeLa M cells were transfected simultaneously with a mixture of three plasmids: (1) shRNA against sororin in pSUPER; (2) either sororinWT–V5 or sororin9A–V5 in a mammalian expression construct; and (3) H2B–GFP to visualize the DNA and to mark transfected cells. Positively transfected cells were then quantified 3 days later to determine whether they were in mitosis or interphase. Multinucleate cells were also counted. Living cells were quantified to avoid loss of mitotic cells during fixation.

The role of the spindle assembly checkpoint in mitotic arrest after sororin knockdown

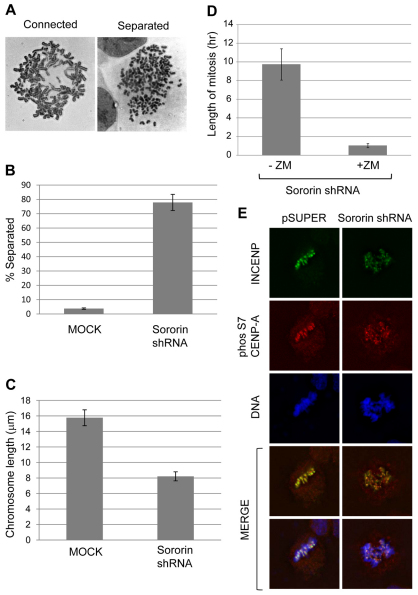

The mitotic block that occurs upon sororin knockdown is most probably triggered by sister chromatids that separate prematurely because of a lack of proper cohesion (Diaz-Martinez et al., 2007; Rankin et al., 2005; Schmitz et al., 2007). Consistent with this idea, transfecting HeLa M cells with sororin shRNA increased the number of cells with separated sister chromatids (Fig. 9A,B). In addition, chromosomes were approximately half as long after sororin knockdown compared with control chromosomes (Fig. 9C). This shortening of chromosomes upon sororin knockdown was previously attributed to hypercondensation during a prolonged mitosis (Rankin et al., 2005). In order to test the role of the SAC in the arrest that occurs upon sororin knockdown, we determined the effect of the Aurora kinase inhibitor, ZM447439, on the mitotic block. Cells transfected with sororin shRNA spent ~10 hours in mitosis, with many cells dying before being able to exit the block (Fig. 9D). When sororin-shRNA-transfected cells were exposed to ZM447439, the length of mitosis was reduced to ~1 hour (Fig. 9D). These results suggest that single sister chromatids activate an Aurora-kinase-dependent mitotic block. Consistent with these findings, we were able to detect punctate staining of histone H3-like centromeric protein (CENP-A), phosphorylated at Ser7, in sororin-shRNA-transfected mitotic cells (Fig. 9E). These areas of staining were closely associated with inner centromere protein (INCENP), a marker for the inner centromere. In the absence of the primary antibody there was some modest cytoplasmic staining using the secondary antibody for CENP-A detection (M.E.B., M.R.D. and W.R.T., unpublished data). Phosphorylation of CENP-A at Ser7 is catalyzed by Aurora kinase, suggesting that chromatids that have prematurely separated are able to recruit this kinase to activate the SAC.

Fig. 9.

Knockdown of sororin causes activation of the spindle assembly checkpoint. (A) Giemsa-staining of chromosomes to show connected and separated chromosomes. The ‘connected’ spread was from mock-transfected HeLa M cells, and the ‘separated’ spread was from HeLa M cells transfected with sororin shRNA. (B) Chromatid separation after sororin knockdown. HeLa M cells transfected with pBABEpuro (mock) or sororin shRNA were analyzed by chromosome dropping 72 hours post-transfection. (C) Sororin shRNA decreases chromosome length. Cells were transfected as in B and chromosome spreads were analyzed using Slidebook software to measure chromosome lengths. (D) Effect of ZM447439 on mitotic arrest induced by sororin knockdown. HeLa M cells were co-transfected with H2B–GFP, used to mark transfected cells, and with sororin shRNA. 72 hours later, the length of mitosis of GFP-positive cells were determined by time-lapse microscopy. In the +ZM sample, 2.5 μM ZM447439 was added 72 hours post-transfection and filming began at the time of drug addition. Values are averages ± s.e.m. (E) Phosphorylated CENP-A in sororin knockdown cells. HeLa M cells were transfected with sororin shRNA, and 72 hours later analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Cells were stained with antibodies to INCENP and CENP-A phosphorylated at Ser7. Examples of mitotic cells are shown.

Discussion

Sister chromatid cohesion is essential for faithful chromosome segregation, keeping sister chromatids together until the exact time at the metaphase–anaphase transition when the duplicated genome is equally segregated to daughter cells. Chromosomes that fail to disjoin contribute to aneuploidy, a condition commonly found in tumor cells. The exact role of aneuploidy in tumor progression is under debate (Schvartzman et al., 2010). It is clear that without sister chromatid cohesion, segregation of complex genomes would be impossible. Sister chromatid cohesion in animal cells is mediated by mechanisms that include chromatin catenation as well as the proteinaceous ring cohesin (Skibbens, 2009; Uhlmann, 2004; Wang et al., 2010). Sororin is a substrate of the APC/C with a key role in sister chromatid cohesion (Rankin et al., 2005). High levels of sororin added to Xenopus laevis extracts cause an increase in cohesin association with metaphase chromosomes, which leads to failed segregation of the sister chromatids (Rankin et al., 2005). In human cells, sororin is essential for cohesion at G2 (Schmitz et al., 2007). Depletion of sororin causes mitotic arrest and failed sister chromatid cohesion, which is comparable to the phenotypes observed upon depletion of shugoshin (Diaz-Martinez et al., 2007).

Sororin is phosphorylated during mitosis, resulting in a reduced electrophoretic mobility. Here we have investigated the role of Cdk1 in sororin phosphorylation and have uncovered a function of this modification in regulating the subcellular localization of the protein. We expressed a GFP-tagged version of sororin and found that it localizes to the nucleus of HeLa M cells, and as previously observed, in mitosis disperses from the chromatin and localizes throughout the cytoplasm. Sororin contains nine residues that match the minimal Cdk consensus, and one potential CIM. GST–sororin is phosphorylated by Cdk1, and mutating the nine serines/threonines followed by proline to alanines severely reduces this phosphorylation. When expressed in HeLa M cells, all of the sororin mutants tested exhibited a reduced electrophoretic mobility after nocodazole treatment, except for sororin9A–V5. This suggests that many phosphorylation sites contribute to the reduced electrophoretic mobility of sororin. Interestingly, sororin9A–GFP remained associated with the chromosomes and the cohesin complex throughout prometaphase, whereas sororoinWT–GFP was dispersed from chromosomes during mitosis. Also, we found that hypophosphorylated sororin precipitates with DNA–cellulose. These results suggest that Cdk1 phosphorylation of sororin releases sororin from the chromosomes by weakening its interaction with the cohesin complex. The precipitation of sororin with DNA–cellulose might indicate an ability to bind to DNA. Alternatively, because these experiments were carried out with cell lysates, sororin might indirectly bind to DNA through the cohesin complex. In either case, phosphorylation appears to influence this association. Sororin is targeted for destruction by the APC/C. Consistent with this, we observed a loss of sororin–GFP intensity after anaphase. The behavior of sororin9A–GFP suggests that loss of phosphorylation at the nine sites does not alter the kinetics of degradation.

In order to narrow down the phosphorylation sites that are needed to remove sororin from the chromatin, we analyzed a number of multi-site mutants of sororin fused to GFP and analyzed their subcellular localization. Interestingly, sororin3A–GFP and sororin6A–GFP showed intermediate phenotypes between sororinWT–GFP and sororin9A–GFP. By increasing the number of sites that were blocked from phosphorylation, we observed a graded increase in the association of sororin with chromosomes. This observation suggests that each site of phosphorylation contributes, in an additive manner, to the release of sororin from chromosomes. Despite the ability of Cdk1 to induce sororin phosphorylation, mutations that are expected to disrupt the putative CIM (R134A; L134A) had little effect on the sororin protein. SororinR134A;L134A was released from chromatin in mitosis, still rescued the mitotic arrest induced by sororin knockdown and also exhibited an electrophoretic mobility shift (R. Coffman, M.R.D. and W.R.T., unpublished data). These observations suggest that Cdk1 phosphorylates sororin in a CIM-independent manner.

Because sororin is involved in sister chromatid cohesion, high levels of a non-phosphorylatable protein might cause defects in cell division, such as impairing the segregation of chromosomes. However, we observed that although overexpressing sororin9A–V5 increased the duration of mitosis, sororinWT–V5 increased the duration of mitosis even more. This difference might be related to the fact that a higher frequency of sororinWT-transfected cells contain lagging chromosomes than sororin9A-expressing cells. It is not known how sororin overexpression increases the frequency of lagging chromosomes. One possibility is that high levels of phosphorylated sororin bind to a cytoplasmic target to interfere with chromosome alignment. Sororin9A might also induce this effect by displacing a population of endogenous sororin from chromosomes. In either case it appears that phosphorylation-competent sororin is linked to the persistence of lagging chromosomes in our studies. The lagging chromosomes we observed were mainly only one or two chromosomes that had not yet aligned to the metaphase plate. This phenotype could be a result of delayed attachments or failure to resolve inappropriate attachments of chromosomes to the spindle.

Sororin appears to antagonize the cohesin destabilizer Wapl (Nishiyama et al., 2010). Phosphorylation of sororin by Cdk1 during prometaphase might be required to neutralize sororin, allowing Wapl to coordinate prophase removal of cohesin from chromosome arms. Consistent with this idea, overexpression of sororin9A increased sister chromatid cohesion, as assessed in chromosome spreads. We also expected that the sororin9A mutant might increase the frequency of chromosome nondisjunction at anaphase; however, this defect was very rare and did not appear to be exacerbated by overexpression of sororin9A (M.R.D. and W.R.T., unpublished data). The fact that cells are able to progress through anaphase in the presence of sororin9A might be taken as evidence that prophase removal of cohesin is not essential for cells to separate chromosomes at anaphase. In support of this idea is the observation that most cells in which Wapl levels are reduced with RNAi still progress from prometaphase to anaphase with normal kinetics, and show no major defects in chromosome separation (Gandhi et al., 2006). This raises the question of the physiological significance of the prophase pathway. Importantly, cells transfected with Wapl RNAi, show a significant increase in the percentage of multi-lobed nuclei, suggesting that mitosis is defective in some cells. This suggests that cleavage of Scc1 by separase is a dominant activity, allowing chromosome segregation even under conditions of suboptimal prophase chromosome resolution. Prophase removal therefore, could be most important in supporting high fidelity chromosome segregation needed to avoid aneuploidy.

Phosphorylation by Cdk1 does not appear to be required to activate sororin to carry out its role in establishing cohesion. This latter point is supported by our observation that sororin9A–V5 can rescue the mitotic block that occurs upon sororin knockdown. This is also consistent with the fact that sororin establishes cohesin during interphase, when Cdk1 activity is low. The mitotic block induced by sororin knockdown is probably triggered by an accumulation of single sister chromatids (Diaz-Martinez et al., 2007; Schmitz et al., 2007). These single chromatids presumably trigger the SAC. Along these lines, we have observed that inhibiting aurora kinases with ZM447439 abolishes the mitotic block induced by sororin knockdown. Aurora B plays an essential role in sensing tension defects at the inner centromere and in triggering the SAC (Nezi and Musacchio, 2009). Aurora B might be acting at the prematurely separated sister chromatids to invoke the SAC-dependent arrest. Along these lines, INCENP still localizes to a region near the centromere after suppressing Scc1 with RNAi, although the localization pattern is altered compared with control cells (Sonoda et al., 2001). This localization of the chromosomal passenger complex to separated sister centromeres might allow Aurora B to constitutively phosphorylate kinetochore targets to destabilize monotelic attachments and activate the SAC. Consistent with this, CENP-A was still phosphorylated at Ser7 in sororin knockdown cells. The fact that sororin9A–V5 can relieve the mitotic block induced by sororin knockdown would be consistent with an ability to establish sister chromatid cohesion. Altogether, our experiments uncover an important role for Cdk1 phosphorylation of sororin in inhibiting its association with the cohesin complex and inactivating its stabilization of cohesion during prometaphase.

Materials and Methods

Cell line and culture conditions

HeLa M cells, a subline of HeLa (Tiwari et al., 1987), were incubated in a humidified atmosphere containing 10% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Mediatech, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals). All chemicals were from Sigma unless otherwise noted. We used 100 ng/ml nocodazole, 2 mM thymidine and 2.5 μM ZM447439 (AstraZeneca). Transfections were carried out using Expressfect (Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ), Fugene (Roche) or polyethyleneimine (Polysciences). A typical experiment in a six-well plate would include 2–5 μg DNA, which was mixed with 50–100 μl of DMEM and 6–15 μl polyethyleneimine (1 mg/ml) followed by a 15 minute incubation before adding to cells. This was scaled up accordingly.

Cloning of sororin

mRNA was isolated from HeLa M cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was carried out using enzymes from Promega. The primers are listed in supplementary material Table S1.

To construct a C-terminal V5-tagged sororin protein, the PCR products were cloned into the pcDNA 3.2 expression vector using TOPO cloning (Invitrogen). All plasmids were confirmed by sequencing.

Coimmunoprecipitation and flow cytometry

Sororin was coimmunoprecipitated with cohesin from chromatin essentially as described previously (Schmitz et al., 2007). SororinWT–V5 and sororin9A–V5 were transiently transfected into HeLa M cells that were then treated with 2 mM thymidine for 24 hours, arresting the cells in S phase. After thymidine was washed off, cells were left either for 6 hours so that they could progress through S phase or blocked in mitosis with nocodazole for 14 hours. Then, the cells were harvested and lysed on ice for 20 minutes in IP buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.7, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol) containing 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM NaF, and protease inhibitors (1 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A). To pellet the chromatin, samples were spun for 10 minutes at 16,000 g (4°C). Pellets were solubilized by sonication and spun at 16,000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was digested with 0.6 IU/μl DNase (Fisher BioReagents) for 20 minutes at 37°C (Schmitz et al., 2007). The immunoprecipitation was performed with an antibody to SMC3 (Millipore) coupled to protein A beads and immunoblotted with an antibody to V5 directly conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX). In order to confirm the position in the cell cycle, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for DNA content, and by chromosome dropping (described below) to quantify mitotic cells. For flow cytometry, cells were collected by trypsinization and fixed in 70% ethanol. Cells were resuspended in PBS and stained with a mixture of propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) and RNase A (5 μg/ml).

Immunoblotting

HeLa M cells were scraped into PBS and then centrifuged (16,000 g, 4°C) for 5 minutes and stored at −80°C. Pellets were lysed by adding RIPA buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% DOC, 0.1% SDS (supplemented with 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM sodium fluoride and 1 mM sodium vanadate) for 20 minutes on ice and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C (Dreier et al., 2009). To ensure equal loading, the protein concentration of each lysate was determined using the BSA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce). Proteins were then separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and the gels were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). The membranes were then blocked for 1.5 hours with blocking buffer, which consisted of 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk dissolved in PBST [PBS containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20], and then incubated with primary antibody for 16 hours (Rabbit-V5 or SMC3; Millipore). The membranes were then washed three times for 10 minutes in PBST. Goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Biorad) were used at a dilution of 1:10,000 in blocking buffer for 1 hour. Membranes were washed again three times for 10 minutes in PBST. Antibody binding was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce).

Analysis of truncated forms of sororin

We identified three exact matches to the Cdk consensus phosphorylation site and one potential cyclin interaction motif (CIM) in the sororin sequence. Sororin contains another six serines/threonines followed by proline that might be Cdk sites. We engineered three different GST fusion proteins, each containing the CIM but lacking a different group of potential phosphorylation sites. PCR, using primers shown in supplementary material Table S1, was used to engineer the GST fusions and the fragments were cloned into pGEX-3X that was digested with EcoRI and BamHI. All plasmids were confirmed by sequencing. In vitro kinase assays were conducted with each GST fusion protein purified from E. coli using glutathione beads. GST fusions were incubated with [32P]ATP and purified Cdk1–cyclin B1 (Cell Signaling). The beads were washed and loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel, which was dried and exposed to film.

Generation of sororin point mutants

QuikChange multi site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) was carried out with the primers shown in supplementary material Table S1 to create point mutations in sororin that we had previously inserted into pcDNA3.2. Gateway cloning (Invitrogen) was used to make GFP constructs with all the point mutants. For this purpose, the mutants were first transferred into the donor vector pDONR 221 from pcDNA3.2. Then, mutants were transferred into destination vector pcDNA-DEST47 to create C-terminal GFP fusions. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing. In some experiments sororin was knocked down using shRNA. For this purpose, a previously defined target sequence, GCCTAGGTGTCCTTGAGCT, was cloned into pSUPER (Oligoengine) (Schmitz et al., 2007).

Chromosome drops

HeLa M cells were blocked in mitosis with nocodazole, exposed to 0.075 M KCl to swell the cells, and fixed with methanol:acetic acid (3:1 v/v) (Taylor et al., 1999). The cells were dropped onto slides, briefly exposed to steam, and stained with Giemsa. Chromosome morphology was determined by a person with no knowledge of the sample origin, and included data from at least two independent experiments performed in triplicate. To distinguish spreads with no sister separation (‘single’) from those with centromere separation, two methods were used. If a spread contained some chromosomes with sister chromatids still attached and others that had completely separated, it was scored as ‘centromere separated’. However, if a spread only contained single chromosome figures, chromosomes were counted to distinguish full cohesion (~92 chromosomes for the tetraploid HeLa genome) or full centromere separation (~184 chromosomes).

DNA binding assay

DNA–cellulose binding assays were performed essentially as described previously (Klein et al., 2006). HeLa M cells were transfected with sororinWT–V5, sororin9A–V5 or pBABEpuro as a negative control using Expressfect (Denville). At 1 day post-transfection, the cells were treated with nocodazole (100 ng/ml) for 16 hours. Cells were lysed (lysis buffer: PBS, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40) and protein concentrations determined using a Bradford assay (Pierce). DNA–cellulose (12 mg) was suspended in 400 μl of protein binding buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% (w/v) Triton X-100], spun, and washed twice. The DNA–cellulose was resuspended in 150 μl of protein binding buffer and distributed into three 50 μl aliquots. Equilibrated lysate was added to each tube of DNA–cellulose and the mixture incubated for 16 hours on a rocker at 4°C. Then, samples were spun at 1500 g for 2 minutes, supernatant was aspirated, and the pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml of protein binding buffer. This wash was repeated three times. Bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blotting with an antibody to the V5 tag (Millipore).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence techniques were carried out as we have described previously (Kaur et al., 2010). Briefly, cells on coverslips were given a brief wash with PBS, fixed with 2% formaldehyde for 15 minutes, followed by permeabilization [150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.7), 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% BSA] for 9 minutes, and blocked with PBS containing 0.1% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature. Lagging chromosomes were quantified in cells transfected with V5-tagged sororinWT or sororin9A. H2A phosphorylated at T121 [H2A T121(P); AssaybioTech] was immunofluorescently stained, and lagging chromosomes were identified by H2A T121(P)-positive centromeres associated with Hoechst 33342-stained chromatin. Only V5-positive cells were included in the analysis. Interkinetochore distances were obtained for cells transfected with V5-tagged sororin. Cells were simultaneously stained with antibodies to Hec1 (Abcam) to mark the kinetochore, H2A T121(P), to mark the inner centromere, and V5 to identify sororin. Hec1-positive dots on either side of a H2A T121(P)-positive dot identified sister kinetochores (supplementary material Fig. S3B). Phosphorylated S7 CENP-A was detected with a polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling). Magnification of images were kept the same within each figure panel.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R15GM084410-01 and R15GM073758-01 to W.R.T. and Sullivan Fellowship and Undergraduate Research and Creative Activity Program Fellowship to M.R.D. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Footnotes

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.085431/-/DC1

References

- Beausoleil S. A., Villen J., Gerber S. A., Rush J., Gygi S. P. (2006). A probability-based approach for high-throughput protein phosphorylation analysis and site localization. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 1285-1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantin G. T., Yi W., Lu B., Park S. K., Xu T., Lee J. D., Yates J. R., 3rd (2008). Combining protein-based IMAC, peptide-based IMAC, and MudPIT for efficient phosphoproteomic analysis. J. Proteome Res. 7, 1346-1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. Q., Yang Q. K., Lu B. W., Yi W., Cantin G., Chen Y. L., Fearns C., Yates J. R., 3rd, Lee J. D. (2009). CDC25B mediates rapamycin-induced oncogenic responses in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 69, 2663-2668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dephoure N., Zhou C., Villen J., Beausoleil S. A., Bakalarski C. E., Elledge S. J., Gygi S. P. (2008). A quantitative atlas of mitotic phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 10762-10767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Martinez L. A., Gimenez-Abian J. F., Clarke D. J. (2007). Regulation of centromeric cohesion by sororin independently of the APC/C. Cell Cycle 6, 714-724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreier M. R., Grabovich A. Z., Katusin J. D., Taylor W. R. (2009). Short and long-term tumor cell responses to Aurora kinase inhibitors. Exp. Cell Res. 315, 1085-1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi R., Gillespie P. J., Hirano T. (2006). Human Wapl is a cohesin-binding protein that promotes sister-chromatid resolution in mitotic prophase. Curr. Biol. 16, 2406-2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnad F., Ren S., Cox J., Olsen J. V., Macek B., Oroshi M., Mann M. (2007). PHOSIDA (phosphorylation site database): management, structural and evolutionary investigation, and prediction of phosphosites. Genome Biol. 8, R250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guacci V., Koshland D., Strunnikov A. (1997). A direct link between sister chromatid cohesion and chromosome condensation revealed through the analysis of MCD1 in S. cerevisiae. Cell 91, 47-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haering C. H., Lowe J., Hochwagen A., Nasmyth K. (2002). Molecular architecture of SMC proteins and the yeast cohesin complex. Mol. Cell 9, 773-788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haering C. H., Farcas A. M., Arumugam P., Metson J., Nasmyth K. (2008). The cohesin ring concatenates sister DNA molecules. Nature 454, 297-301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauf S., Roitinger E., Koch B., Dittrich C. M., Mechtler K., Peters J. M. (2005). Dissociation of cohesin from chromosome arms and loss of arm cohesion during early mitosis depends on phosphorylation of SA2. PLoS Biol. 3, e69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. C., Shi J., Orth J. D., Mitchison T. J. (2009). Evidence that mitotic exit is a better cancer therapeutic target than spindle assembly. Cancer Cell 16, 347-358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P., Hardy S., Morgan D. O. (1998). Nuclear localization of cyclin B1 controls mitotic entry after DNA damage. J. Cell Biol. 141, 875-885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H., Bekier M. E., Taylor W. R. (2010). Regulation of Borealin by phosphorylation at serine 219. J. Cell. Biochem. 111, 1291-1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima T. S., Sakuno T., Ishiguro K., Iemura S., Natsume T., Kawashima S. A., Watanabe Y. (2006). Shugoshin collaborates with protein phosphatase 2A to protect cohesin. Nature 441, 46-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein U. R., Nigg E. A., Gruneberg U. (2006). Centromere targeting of the chromosomal passenger complex requires a ternary subcomplex of Borealin, Survivin, and the N-terminal domain of INCENP. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 2547-2558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafont A. L., Song J., Rankin S. (2010). Sororin cooperates with the acetyltransferase Eco2 to ensure DNA replication-dependent sister chromatid cohesion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 20364-20369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maresca T. J., Salmon E. D. (2010). Welcome to a new kind of tension: translating kinetochore mechanics into a wait-anaphase signal. J. Cell Sci. 123, 825-835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis C., Ciosk R., Nasmyth K. (1997). Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell 91, 35-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M., Kumada K., Hatakeyama K., Noda T., Peters J. M., Hirota T. (2007). The complete removal of cohesin from chromosome arms depends on separase. J. Cell Sci. 120, 4188-4196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezi L., Musacchio A. (2009). Sister chromatid tension and the spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 785-795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama T., Ladurner R., Schmitz J., Kreidl E., Schleiffer A., Bhaskara V., Bando M., Shirahige K., Hyman A. A., Mechtler K., et al. (2010). Sororin mediates sister chromatid cohesion by antagonizing wapl. Cell 143, 737-749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J. V., Blagoev B., Gnad F., Macek B., Kumar C., Mortensen P., Mann M. (2006). Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell 127, 635-648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onn I., Heidinger-Pauli J. M., Guacci V., Unal E., Koshland D. E. (2008). Sister chromatid cohesion: a simple concept with a complex reality. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 24, 105-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizza S., Tanaka T., Hochwagen A., Eisenhaber F., Nasmyth K. (2000). Pds5 cooperates with cohesin in maintaining sister chromatid cohesion. Curr. Biol. 10, 1557-1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin S., Ayad N. G., Kirschner M. W. (2005). Sororin, a substrate of the anaphase-promoting complex, is required for sister chromatid cohesion in vertebrates. Mol. Cell 18, 185-200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J., Watrin E., Lenart P., Mechtler K., Peters J. M. (2007). Sororin is required for stable binding of cohesin to chromatin and for sister chromatid cohesion in interphase. Curr. Biol. 17, 630-636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schvartzman J. M., Sotillo R., Benezra R. (2010). Mitotic chromosomal instability and cancer: mouse modelling of the human disease. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 102-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintomi K., Hirano T. (2009). Releasing cohesin from chromosome arms in early mitosis: opposing actions of Wapl-Pds5 and Sgo1. Genes Dev. 23, 2224-2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skibbens R. V. (2009). Establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Curr. Biol. 19, R1126-R1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda E., Matsusaka T., Morrison C., Vagnarelli P., Hoshi O., Ushiki T., Nojima K., Fukagawa T., Waizenegger I. C., Peters J. M., et al. (2001). Scc1/Rad21/Mcd1 is required for sister chromatid cohesion and kinetochore function in vertebrate cells. Dev. Cell 1, 759-770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumara I., Vorlaufer E., Gieffers C., Peters B. H., Peters J. M. (2000). Characterization of vertebrate cohesin complexes and their regulation in prophase. J. Cell Biol. 151, 749-762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumara I., Vorlaufer E., Stukenberg P. T., Kelm O., Redemann N., Nigg E. A., Peters J. M. (2002). The dissociation of cohesin from chromosomes in prophase is regulated by Polo-like kinase. Mol. Cell 9, 515-525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor W. R., DePrimo S. E., Agarwal A., Agarwal M. L., Schonthal A. H., Katula K. S., Stark G. R. (1999). Mechanisms of G2 arrest in response to overexpression of p53. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 3607-3622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari R. K., Kusari J., Sen G. C. (1987). Functional equivalents of interferon-mediated signals needed for induction of an mRNA can be generated by double-stranded RNA and growth factors. EMBO J. 6, 3373-3378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubersax J. A., Woodbury E. L., Quang P. N., Paraz M., Blethrow J. D., Shah K., Shokat K. M., Morgan D. O. (2003). Targets of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdk1. Nature 425, 859-864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann F. (2004). The mechanism of sister chromatid cohesion. Exp. Cell Res. 296, 80-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoof D., Munoz J., Braam S. R., Pinkse M. W., Linding R., Heck A. J., Mummery C. L., Krijgsveld J. (2009). Phosphorylation dynamics during early differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 5, 214-226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waizenegger I. C., Hauf S., Meinke A., Peters J. M. (2000). Two distinct pathways remove mammalian cohesin from chromosome arms in prophase and from centromeres in anaphase. Cell 103, 399-410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. H., Mayer B., Stemmann O., Nigg E. A. (2010). Centromere DNA decatenation depends on cohesin removal and is required for mammalian cell division. J. Cell Sci. 123, 806-813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]