Abstract

During induction of the Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodite vulva, a signal from the anchor cell activates the LET-23 epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)/LET-60 Ras/MPK-1 MAP kinase signaling pathway in the vulval precursor cells. We have characterized two mechanisms that limit the extent of vulval induction. First, we found that gap-1 may directly inhibit the LET-60 Ras signaling pathway. We identified the gap-1 gene in a genetic screen for inhibitors of vulval induction. gap-1 is predicted to encode a protein similar to GTPase-activating proteins that likely functions to inhibit the signaling activity of LET-60 Ras. A loss-of-function mutation in gap-1 suppresses the vulvaless phenotype of mutations in the let-60 ras signaling pathway, but a gap-1 single mutant does not exhibit excess vulval induction. Second, we found that let-23 EGFR prevents vulval induction in a cell-nonautonomous manner, in addition to its cell-autonomous role in activating the let-60 ras/mpk-1 signaling pathway. Using genetic mosaic analysis, we show that let-23 activity in the vulval precursor cell closest to the anchor cell (P6.p) prevents induction of vulval precursor cells further away from the anchor cell (P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p). This result suggests that LET-23 in proximal vulval precursor cells might bind and sequester the inductive signal LIN-3 EGF, thereby preventing diffusion of the inductive signal to distal vulval precursor cells.

Keywords: C. elegans, vulval induction, GTPase-activating protein, gap-1, receptor tyrosine kinase, let-23, Ras, let-60

Growth factor signals that are received by receptor tyrosine kinases play a central role in cellular proliferation and differentiation. To prevent excessive cell growth or premature cell differentiation, it is important to down-regulate these signaling pathways. We have used a genetic screen in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans to identify genes that antagonize the activity of the receptor tyrosine kinase/Ras/MAP kinase signaling pathway.

Activation of a receptor tyrosine kinase/Ras/MAP kinase signaling pathway induces the vulva of the C. elegans hermaphrodite. Six epithelial vulval precursor cells in the ventral midline (P3.p through P8.p) have equivalent developmental potentials and may adopt one of three possible cell fates (Sternberg and Horvitz 1986; Kornfeld 1997). A signal from the anchor cell in the somatic gonad induces the vulval precursor cell closest to the anchor cell (P6.p) to generate eight descendants that form the center of the developing vulva, a lineage designated the primary (1°) cell fate (Kimble 1981; Sternberg and Horvitz 1986). On induction, P6.p sends a lateral signal that induces the adjacent vulval precursor cells (P5.p and P7.p) to generate seven descendants that form the outer part of the developing vulva, a lineage designated the secondary (2°) cell fate (Sternberg 1988; Koga and Ohshima 1995; Simske and Kim 1995). The three remaining vulval precursor cells that are not induced by the anchor cell or lateral signal (P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p) divide once and then fuse with the surrounding syncytium formed by hyp7, a lineage designated the tertiary (3°) cell fate (Sulston and Horvitz 1977). Some experiments have suggested that the anchor cell signal can induce expression of the 2° cell fate by P5.p and P7.p in the absence of a lateral signal (Sternberg and Horvitz 1986; Thomas et al. 1990; Katz et al. 1995).

Reception of the anchor cell signal by P6.p activates an evolutionarily conserved receptor tyrosine kinase/Ras/MAP kinase signaling pathway (for review, see Kornfeld 1997). lin-3 encodes a protein similar to epidermal growth factor (EGF) that is likely to be the anchor cell signal (Hill and Sternberg 1992). let-23 encodes the putative receptor for the anchor cell signal and is similar to vertebrate receptor tyrosine kinases such as EGF receptors (EGFRs) (Aroian et al. 1990). sem-5 encodes a protein with two SH3 domains and one SH2 domain similar to vertebrate GRB2 (Clark et al. 1992). GRB2 is an adaptor protein that binds to activated EGFR and to a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GNEF), thereby recruiting GNEF to the plasma membrane, where it can activate Ras (Lowenstein et al. 1992; Olivier et al. 1993; Simon et al. 1993). let-60 encodes a Ras protein that transduces the inductive signal downstream of let-23 (Beitel et al. 1990; Han et al. 1990). lin-45, mek-2, and mpk-1/sur-1 encode proteins similar to Raf, MEK, and MAP kinase, respectively (Han et al. 1993; Lackner et al. 1994; Wu and Han 1994; Kornfeld et al. 1995; Wu et al. 1995). These three serine/threonine kinases act in a sequential cascade downstream of LET-60 Ras. Loss-of-function mutations in the genes described above cause the vulval precursor cells to express the uninduced 3° cell fate instead of the 1° or 2° vulval cell fates, resulting in a vulvaless (Vul) phenotype.

In addition to genes that activate vulval induction, several genes have been identified that repress vulval induction. These genes include the synthetic multivulva genes, which constitute two functionally redundant pathways (termed A and B) that are believed to generate an inhibitory signal in the hypodermal tissue (hyp7) surrounding the vulval precursor cells and transduce it in the vulval precursor cells themselves (Ferguson and Horvitz 1989; Herman and Hedgecock 1990). In double mutant animals containing loss-of-function mutations in both a class A and a class B synthetic multivulva gene, all vulval precursor cells express induced 1° or 2° cell fates, resulting in a multivulva (Muv) phenotype. Single mutant animals containing only a class A or a class B mutation exhibit wild-type patterns of vulval induction (Ferguson and Horvitz 1989). Other genes that function to inhibit vulval induction include sli-1, which encodes a protein similar to the mammalian c-cbl oncogene (Yoon et al. 1995) and unc-101, which encodes a protein similar to vertebrate clathrin-associated proteins (Lee et al. 1994).

To identify additional genes that repress the activity of the anchor cell signaling pathway, we have carried out a genetic screen for mutations that suppress the Vul phenotype of lin-2 or lin-10 mutants (Horvitz and Sulston 1980; Ferguson and Horvitz 1985). lin-2 and lin-10 function along with lin-7 to localize LET-23 EGFR to the basolateral membrane domain of the vulval precursor cells (Simske et al. 1996; C. Whitfield, unpubl.). In lin-2, lin-7, or lin-10 mutants, LET-23 EGFR is predominantly mislocalized to the apical membrane compartment of the vulval precursor cells where it cannot receive the inductive signal. Thus, mislocalization of LET-23 causes a Vul phenotype (Hoskins et al. 1996; Simske et al. 1996; C. Whitfield, pers. comm.). lin-2 encodes a membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) (Hoskins et al. 1996), and lin-7 encodes a protein with a single PDZ (PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1) motif (Simske et al. 1996).

In this report, we describe the isolation, molecular cloning, and genetic analysis of gap-1, an inhibitor of vulval induction. gap-1 encodes a protein similar to Ras GTPase-activating proteins (RasGAPs) from Drosophila and vertebrates (Gaul et al. 1992; Maekawa et al. 1994; Baba et al. 1995). RasGAPs decrease the signaling activity of Ras by stimulating its intrinsic GTPase activity, thereby lowering the levels of GTP-bound, active Ras (Bollag and McCormick 1991; Boguski and McCormick 1993). The genetic and molecular data indicate that GAP-1 most likely functions to repress vulval induction by stimulating the GTPase activity of LET-60 Ras, but GAP-1 does not function as an effector to transduce the anchor cell signal.

Furthermore, we observed that a reduction of let-23 EGFR activity causes excess vulval induction in a gap-1 null mutant, suggesting that let-23 may have an inhibitory function during vulval cell fate specification in addition to its inductive role. Aroian and Sternberg have previously proposed such an inhibitory activity of let-23 based on the Muv phenotype caused by a let-23 reduction-of-function allele (Aroian and Sternberg 1991). However, the mechanism for this antagonistic activity is poorly understood. Our genetic analysis indicates that lin-2, lin-7, and lin-10 are also required for the let-23 antagonistic function. Furthermore, using genetic mosaic analysis, we show that let-23 prevents vulval induction in a cell-nonautonomous fashion. On the basis of this analysis, we propose that LET-23 EGFR in the vulval precursor cell closest to the anchor cell (P6.p) may prevent induction of vulval precursor cells further away from the anchor cell (P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p) by binding and sequestering the anchor cell signal LIN-3 EGF.

Results

Isolation of gap-1 mutations

To identify new genes that function to inhibit vulval induction, we performed genetic screens for mutations that suppress the Vul phenotype of lin-2 and lin-10 mutants. We chose lin-2 and lin-10 because mutations in these genes reduce, but do not eliminate, the activity of the let-23 EGFR/let-60 ras signaling pathway (Ferguson and Horvitz 1985). We reasoned that mutations in inhibitory genes might compensate for the weak signaling defects in lin-2 or lin-10 mutants, but they might not restore signaling if the signaling pathway is completely blocked, for example, as in animals containing null mutations in let-23 or let-60. The screen for lin-2 and lin-10 suppressors is efficient because >99% of lin-2(n1610) and lin-10(n1390) mutant animals are egg-laying defective due to the absence or incomplete formation of the vulva, and one suppressed animal can lay many eggs that are easily isolated from a large population of Vul animals.

A first suppressor mutation, n1329, was isolated from a mutator strain in a screen for suppressors of the lin-10(n1299) Vul phenotype (Kim and Horvitz 1990). Subsequently, we used lin-10(n1390) or lin-2(n1610) hermaphrodites in our genetic screens because these mutations cause a more penetrant Vul phenotype than lin-10(n1299). From the F2 progeny of mutagenized lin-2(n1610) or lin-10(n1390) animals, we isolated >60 mutations with a recessive suppressor phenotype. Eleven mutations failed to complement n1329 for suppression of the lin-10 Vul phenotype, and we refer to this gene as gap-1 because it encodes a protein similar to GTPase-activating proteins (see below).

Molecular cloning of gap-1

We have cloned gap-1 to understand how it functions at the molecular level. Using three-factor crosses, we mapped gap-1 to the left arm of LGX between unc-1 and unc-2, within ∼0.1 map units of dpy-3 (Fig. 1A). Next, we determined that gap-1 was to the right of one restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP; gaP21) and within 0.15 map units of another polymorphism (pkP670) (see Materials and Methods). Because there are ∼100 Mb of DNA and 300 cM in the C. elegans genome (Wood 1988), gap-1 is likely located within ∼50 kb of the pkP670 RFLP.

Figure 1.

Molecular cloning of gap-1. (A) Genetic and physical maps of the gap-1 region on the X chromosome. The positions of the RFLPs (gaP21,pkP670) and a set of cosmid and yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) clones that cover the gap-1 region are shown. (B) Intron–exon structure of gap-1. Solid boxes indicate exons. The positions of the Tc1 insertion in n1329, the 334-bp deletion in ga133 and the point mutations in n1691, ga14, ga12, and n1683 are indicated. (C) Transformation rescue experiments. The structures and activities of the gap-1 DNA fragments used for germ-line transformation of gap-1(ga133) lin-2(n397) animals are shown. (% Vul) The fraction of transformants that exhibited a Vul phenotype; (n) the number of stable transformants examined.

We were able to identify the gap-1 locus by finding DNA rearrangements in two gap-1 mutants. We analyzed genomic DNA of eight gap-1 mutants on Southern blots using cosmids or cosmid fragments from the region around pkP670 as probes. A 4.6-kb fragment amplified from the cosmid T24C12 (see Materials and Methods) detected a 1.6-kb insertion associated with gap-1(n1329) and a 0.3-kb deletion associated with gap-1(ga133) (Fig. 1B). The C. elegans genome sequencing project has determined the sequence of the region corresponding to the 4.6-kb probe. Analysis of the DNA sequence in this region with the genefinder program (Favello et al. 1995) predicts that this region contains a single gene (Fig. 1B). The predicted mRNA splicing pattern of this gene was verified by sequence analysis of cDNAs isolated in RT–PCR experiments (see Materials and Methods). These experiments detected a single splice form of a mRNA containing one long open reading frame predicted to encode a protein of 629 amino acids with a molecular weight of 71.2 kD. The predicted initiation codon is preceded by an in-frame stop codon at position −8, and the termination codon is followed by a polyadenylation signal (Fig. 2; data not shown).

Figure 2.

Sequence of gap-1 cDNA and mutations in gap-1 alleles. Nucleotide and predicted protein sequence of gap-1. The position of the Tc1 insertion in n1329, the breakpoints of the deletion in ga133 and the nucleotide changes in n1691, ga12, ga14, and n1683 are indicated. The region between amino acids 115 and 358 that corresponds to the catalytic domain of GAP-1 is underlined.

Two lines of evidence indicate that the cDNA sequence shown in Figure 2 is encoded by the gap-1 gene. First, we have identified an insertion, a deletion, and four point mutations in this gene. Sequence analysis of DNA amplified from gap-1(n1329) animals revealed an insertion of a Tc1 transposon in exon 2 after amino acid 130 (Fig. 2). DNA from gap-1(ga133) mutants contains a deletion of 334 bp removing part of exon 3 and all of exon 4 (Fig. 1B). This deletion is predicted to disrupt the normal splicing pattern and shift the translational reading frame of the mRNA, resulting in a truncation of GAP-1 after amino acid 161 (Fig. 2). Next, we showed that the alleles n1691, ga14, ga12, and n1683 contain stop mutations that are predicted to truncate the GAP-1 protein after amino acids 149, 172, 181, and 427, respectively (Figs. 1B and 2).

Second, we have rescued the gap-1(ga133) mutant phenotype in germ-line transformation experiments. As described below, gap-1(ga133) strongly suppresses the Vul phenotype of lin-2(n397). We used PCR to amplify a 9.7-kb DNA fragment that contains the entire gap-1 gene from genomic DNA of wild-type animals. This DNA fragment partially rescued the suppressed phenotype of gap-1(ga133) lin-2(n397) double mutants in germ-line transformation experiments (Fig. 1C). As a negative control, we showed that a 9.4-kb DNA fragment isolated from genomic DNA of gap-1(ga133) mutant animals did not exhibit any significant rescuing activity when compared with uninjected animals (Fig. 1C).

gap-1 encodes a protein similar to RasGTPase-activating proteins

Comparison of the GAP-1 protein sequence to the sequences of proteins in the GenBank and EMBL databases by use of the BLAST algorithm (Altschul et al. 1990) revealed a strong similarity between GAP-1 and Ras GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) from yeast, Drosophila and vertebrates. C. elegans GAP-1 is most similar to Drosophila Gap-1 (34% identity and 57% similarity) (Gaul et al. 1992) and vertebrate Gap-1m (36% identity and 58% similarity) (Maekawa et al. 1994; Baba et al. 1995). Other GAPs, such as p120 RasGAP or the human neurofibromatosis type-1 (NF-1) protein are less similar but still related to C. elegans GAP-1 (Boguski and McCormick 1993). The most highly conserved region is the catalytic domain located between amino acids 115 and 358 (Fig. 3). Outside the region encoding the catalytic domain, GAP-1 does not display any significant sequence similarity to other known proteins. In particular, GAP-1 does not contain the SH2 or SH3 domains that are found in p120 RasGAP.

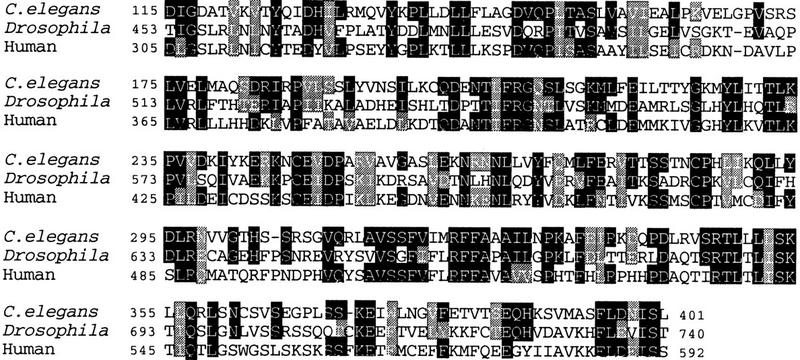

Figure 3.

Sequence similarity between C. elegans GAP-1 and other GAPs. Alignment of the catalytic domains of C. elegans GAP-1, Drosophila Gap-1 (Gaul et al. 1992) and human Gap-1m (Baba et al. 1995) GAP proteins with the ClustalW program (Higgins and Sharp 1988). (Solid boxes) identical residues; (shaded boxes) conservative substitutions. Apart from the catalytic domain, no other significant similarity exists between C. elegans GAP-1 and other proteins in the databases.

Ras proteins cycle between GTP- and GDP-bound states (for review, see Boguski and McCormick 1993). GTP-bound Ras adopts an active conformation that can bind and activate Raf kinases and possibly other effector molecules. GDP-bound Ras is in an inactive conformation and cannot bind or activate its effector molecules. RasGAPs inhibit the signaling activity of Ras by stimulating its GTPase activity, thereby decreasing the fraction of Ras that is in the GTP-bound, active state (Boguski and McCormick 1993). The activity of RasGAPs is opposed by the activity of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GNEFs) that activate Ras by promoting the exchange of GDP for GTP. Activation of receptor tyrosine kinases stimulates GNEF activity and results in higher levels of GTP-bound, active Ras. In analogy to other RasGAPs, C. elegans GAP-1 might decrease the signaling activity of LET-60 Ras by stimulating its GTPase activity.

Our molecular analysis suggests that the ga133 deletion and the ga12, ga14, and n1691 stop mutations may severely reduce or completely eliminate gap-1 activity, because these mutations are predicted to truncate GAP-1 before the region required for the interaction with Ras (amino acids 179–358) (Scheffzek et al. 1996). Therefore, we used the gap-1(ga133) deletion allele in all subsequent genetic experiments.

gap-1 inhibits vulval induction

To study how gap-1 functions during vulval induction, we examined how gap-1(ga133) affects the specification of vulval cell fates. First, we showed that gap-1(ga133) mutants do not exhibit any obvious developmental defects. Specifically, in gap-1(ga133) animals, vulval induction appears normal (Table 1, Fig. 4), and the vulval precursor cells adopt a normal pattern of cell fates (Table 2A,B). Furthermore, we did not observe any sterility or lethality in gap-1(ga133) animals.

Table 1.

Genetic interactions between gap-1 and genes that control vulval induction

| Row

|

Genotypea

|

Percent

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulb

|

wild type

|

Muvb

|

No.

|

||

| 1 | N2 | 0 | 100 | 0 | many |

| 2 | gap-1 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 280 |

| 3 | lin-3 | 88 ± 5 | 12 ± 5 | 0 | 189 |

| 4 | lin-3; gap-1 | 42 ± 6 | 58 ± 6 | 0 | 238 |

| 5 | lin-2 | 93 ± 4 | 7 ± 4 | 0 | 185 |

| 6 | gap-1 lin-2 | 4 ± 3 | 22 ± 6 | 74 ± 6 | 197 |

| 7 | gap-1 lin-2; gaEx50[let-23] | 0 | 99 ± 2 | 1 ± 2 | 149 |

| 8 | lin-7 | 85 ± 4 | 13 ± 4 | 1 ± 1 | 357 |

| 9 | lin-7; gap-1 | 2 ± 2 | 17 ± 5 | 81 ± 5 | 228 |

| 10 | lin-7; gap-1; gaEx50[let-23] | 0 | 97 ± 3 | 3 ± 3 | 143 |

| 11 | lin-10 | 94 ± 3 | 6 ± 3 | 0 | 203 |

| 12 | lin-10; gap-1 | 6 ± 3 | 31 ± 7 | 63 ± 7 | 177 |

| 13 | lin-10; gap-1; gaEx50[let-23] | 0 | 100 | 0 | 96 |

| 14 | let-23(sy1) | 80 ± 4 | 20 ± 4 | 0 | 427 |

| 15 | let-23(sy1); gap-1 | 3 ± 2 | 24 ± 5 | 73 ± 6 | 238 |

| 16 | let-23(sy10) | 89 ± 10 | 11 ± 10 | 0 | 36 |

| 17 | let-23(sy10); gap-1 | 0 | 2 ± 6 | 98 ± 6 | 35 |

| 18 | sem-5 | 91 ± 3 | 9 ± 3 | 0 | 292 |

| 29 | gap-1 sem-5 | 41 ± 6 | 59 ± 6 | 0 | 306 |

| 20 | let-60c | 100d | 0 | 0 | >200d |

| 21 | let-60; gap-1c | 14 ± 14 | 86 ± 14 | 0 | 22 |

| 22 | lin-45e | 76 ± 6 | 24 ± 6 | 0 | 186 |

| 23 | lin-45; gap-1e | 72 ± 5 | 28 ± 5 | 0 | 341 |

| 24 | lin-15e | 0 | 98 ± 2 | 2 ± 2 | 172 |

| 25 | lin-15; gap-1e | 0 | 33 ± 6 | 67 ± 6 | 208 |

Alleles used: gap-1(ga133); lin-3(e1417); lin-2(n397), lin-7(e1449); lin-10(n1390); sem-5(n2019); let-60(n1876); lin-45(n2018ts); and lin-15(n765ts). Strains containing lin-3(e1417) and let-23(sy10) also contained the cis-acting mutations unc-5(e53) and unc-4(e120), respectively.

Vulval induction in the different strains was scored by inspecting the phenotype of the animals under a dissecting microscope. Vulvaless (Vul) animals accumulate eggs in their gonads and die when their progeny hatches within the animals, producing “bags” of worms. Multivulva (Muv) animals are characterized by two or more ventral protrusions next to the position of the normal vulva. The percentage of animals with each given phenotype is shown (±95% confidence interval). (No.) The number of animals scored.

For these strains, we scored the progeny that was segregated from let-60(n1876)/dpy-20(e1302) unc-22(e66) parents.

Data from Beitel et al. (1990).

Strains containing the cold-sensitive lin-45(n2018) and the heat-sensitive lin-15(n765) mutations were scored at 14°C.

Figure 4.

Vulval phenotypes of gap-1 and let-23 single and double mutants. Nomarski photomicrographs of lateral views of animals at the L4 larval stage. Vulval tissue generated from 1° and 2° cells (arrows) and hypodermal tissue generated from 3° cells (bars) are indicated. Anterior is to the left, and ventral is below. Scale bar, 10 μm. Alleles used: let-23(sy1) and gap-1(ga133).

Table 2.

Vulval lineages in let-23 and gap-1 single and double mutants

| Genotype

|

P3.p

|

P4.p

|

P5.p

|

P6.p

|

P7.p

|

P8.p

|

No.

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The cleavage planes of the third round of vulval cell division are indicated as follows: (T) Transverse division; (O) for oblique division; (L) longitudinal division; (N) cell that did not divide; (S) cell that fused with the hypodermis after the first round of cell division. Underlined letters indicate cells that adhered to the ventral hypodermis. Thick boxes indicate 1° or 1°-like cell fates with O instead of T divisions, thin boxes indicate 2° or a 2°-like cell fate where P5.ppa underwent an O instead of a T division, and shaded boxes indicate hybrid cell fates. (No.) Number of animals observed. Alleles used: let-23(sy1) and gap-1(ga133).

Second, we showed that loss of gap-1 function suppresses the Vul phenotype caused by mutations in lin-2, lin-7, and lin-10 (Table 1). These three genes may function together to localize LET-23 EGFR to the basolateral membrane domain of the vulval precursor cells (Simske et al. 1996).

Third, we showed that gap-1(ga133) suppresses the Vul phenotype caused by many other genes that act in the let-23 EGFR/let-60 ras signaling pathway. We generated double mutant strains between gap-1(ga133) and mutations in each of the following genes: lin-3 EGF, let-23 EGFR, sem-5 GRB2, let-60 ras, and lin-45 raf. gap-1(ga133) strongly suppresses the Vul phenotype of let-23(sy1 or sy10) and let-60(n1876), weakly suppresses the Vul phenotype of lin-3(e1417) and sem-5(n2019) and does not suppress the Vul phenotype of lin-45(n2018ts), although this mutation causes a weaker Vul phenotype than any of the other mutations that were tested (Table 1).

Fourth, we asked if gap-1(ga133) might cause a synthetic Muv phenotype with the lin-8(n111) class A or the lin-9(n112) class B synthetic multivulva mutations (Ferguson and Horvitz 1989). We found that both lin-8(n111); gap-1(ga133) and lin-9(n112); gap-1(ga133) double mutants are non-Muv (data not shown). Because animals containing both a class A and a class B synthetic multivulva mutation exhibit a Muv phenotype, these results indicate that gap-1 does not belong to either class of synthetic multivulva genes. gap-1(ga133), however, enhances the phenotype of a weak synthetic multivulva mutant. lin-15 encodes two proteins, LIN-15A and LIN-15B, that provide class A and class B activity, respectively (Clark et al. 1994; Huang et al. 1994). lin-15(n765ts) is a temperature-sensitive mutation that affects both class A and class B activity. Few lin-15(n765ts) single mutants, but most gap-1(ga133) lin-15(n765ts) double mutants, exhibit a Muv phenotype at 14°C (Table 1).

In summary, our genetic analyses indicate that gap-1(+) inhibits vulval induction because loss of gap-1 function suppresses the Vul phenotype caused by mutations in several genes that act in the let-23 EGFR/let-60 ras pathway, enhances the Muv phenotype of a weak lin-15 mutation, but does not cause excess vulval induction in a single mutant.

Reduction of let-23 EGFR activity causes a Muv phenotype in gap-1(ga133) animals

Double mutants between gap-1(ga133) and lin-2(n397), lin-7(e1449), lin-10(n1390), or let-23(sy1 or sy10) exhibit a Muv phenotype (Table 1). We followed the entire pattern of vulval precursor cell divisions in let-23(sy1); gap-1(ga133) animals and observed that P3.p, P4.p, or P8.p frequently expressed induced (1° or 2°) vulval cell fates (Table 2D and Fig. 4). These results are surprising because these lin-2, lin-7, lin-10, and let-23 mutations cause a Vul phenotype in single mutants (Table 1, Table 2C, and Fig. 4), yet they cause excess vulval induction in double mutants with gap-1(ga133).

A common feature of the mutations that cause a Muv phenotype in double mutants with gap-1(ga133) is that they each reduce the activity of let-23 EGFR. let-23(sy10) is a missense mutation in the cysteine-rich region of the extracellular domain that might reduce the affinity of LET-23 EGFR for its putative ligand LIN-3 EGF or prevent ligand-induced activation (Aroian et al. 1993). let-23(sy1) is a stop mutation that deletes the last six amino acids of LET-23 EGFR, which include the LIN-7-binding site (Aroian et al. 1993; Simske et al. 1996; S. Kaech, pers. comm.). let-23(sy1), lin-2(n397), lin-7(e1449), and lin-10(n1390) may affect signaling in a similar manner because LET-23 EGFR is apically mislocalized and its signaling activity is reduced to a similar extent in mutants containing each of these four alleles (Kim and Horvitz 1990; Aroian et al. 1993; Hoskins et al. 1996; Simske et al. 1996). We also showed that overexpression of let-23(+) from an extrachromosomal array (gaEx50) suppresses the Muv phenotype of gap-1(ga133) lin-2(n397), lin-7(e1449); gap-1(ga133) or lin-10(n1390); gap-1(ga133) animals (Table 1). This result indicates that the Muv phenotype of these animals is caused by a decrease in let-23 activity. In contrast to mutations that reduce the signaling activity of LET-23, mutations in genes that act upstream (lin-3) or downstream of let-23 (sem-5, let-60, and lin-45) do not display a Muv phenotype in double mutants with gap-1(ga133) (Table 1).

Finally, we showed that vulval induction in let-23(sy1); gap-1(ga133) double mutants depends on activation of LET-23 EGFR by the anchor cell signal. We used a laser microbeam to ablate the entire somatic gonad at the first larval stage, which includes the cells that normally give rise to the anchor cell during the second larval stage (see Materials and Methods). In each of the 10 let-23(sy1); gap-1(ga133) gonad-ablated animals, all six vulval precursor cells adopted the 3° uninduced cell fate resulting in a Vul phenotype (Table 2E).

In summary, our data indicate that a secondary function of let-23 EGFR is to prevent excess vulval induction, because let-23 reduction-of-function mutations cause an increase in vulval induction when combined with a mutation in gap-1. Furthermore, this secondary function requires the activities of lin-2, lin-7, and lin-10. Our results confirm and extend previous work, which showed that let-23(n1045) (Aroian and Sternberg 1991) as well as certain alleles of lin-2, lin-7, and lin-10 (Horvitz and Sulston 1980; Ferguson and Horvitz 1985; R. Hoskins, pers. comm.) could preferentially affect the secondary inhibitory function of LET-23 EGFR and result in a weak Muv phenotype (Ferguson and Horvitz 1985).

let-23 EGFR antagonizes vulval induction in a cell-nonautonomous fashion

One possible explanation for the inhibitory function of let-23 is that it could activate a cell-autonomous inhibitory pathway in parallel to activating the let-60 ras pathway. Alternatively, let-23 could prevent the expression of vulval cell fates in a cell-nonautonomous fashion; for example, LET-23 EGFR in P6.p might bind and sequester the anchor cell signal LIN-3, thereby preventing the signal from reaching vulval precursor cells farther away from the anchor cell.

To distinguish between these two possibilities, we performed a let-23 mosaic analysis in let-23(sy1); gap-1(ga133) double mutant animals. In nonmosaic let-23(sy1); gap-1(ga133) animals, P3.p, P4.p, or P8.p often express induced (1° or 2°) vulval cell fates instead of the uninduced (3°) cell fate, resulting in a Muv phenotype (Table 2D). We identified mosaic animals in which some cells (including P3.p, P4.p, or P8.p) lacked let-23(+) whereas other cells expressed let-23(+) and determined whether the cell fates adopted by P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p were affected by the presence of let-23(+) activity in neighboring vulval precursor cells (P5.p, P6.p, or P7.p). If the let-23 inhibitory function is cell autonomous, then P3.p, P4.p, or P8.p will express induced (1° or 2°) vulval cell fates if they lack let-23(+) and gap-1(+) activity regardless of the genotype of neighboring cells. On the other hand, if let-23 inhibits the expression of vulval cell fates in a cell-nonautonomous fashion, then P3.p, P4.p, or P8.p may not express induced vulval cell fates because of an inhibitory let-23(+) activity in neighboring vulval precursor cells (P5.p, P6.p, or P7.p).

To perform this mosaic analysis, we constructed a strain in which let-23(+) and the cell-autonomous lineage marker ncl-1(+) were expressed from an extrachromosomal array and the chromosomal copies of let-23, ncl-1, and gap-1 were mutant. The ncl-1 mutation causes many cells, including the vulval precursor cells, to exhibit an enlarged nucleolus (Hedgecock and Herman 1995; Miller et al. 1996). Spontaneous loss of the ncl-1(+) let-23(+) extrachromosomal array during development generates a clone of mutant cells. The point in the lineage at which the extrachromosomal array has been lost can be inferred by scoring of the Ncl phenotype of individual cells and with knowledge of the C. elegans cell lineage.

We found three mosaic animals that lacked let-23(+) in all six vulval precursor cells because of a loss of the extrachromosomal array in AB or AB.p (see Materials and Methods). These three animals displayed a Muv phenotype, suggesting that the inhibitory activity of let-23 has a site of action within the vulval precursor cells (data not shown).

To distinguish between cell-autonomous and cell-nonautonomous inhibition by let-23(+), we identified cases in which some vulval precursor cells expressed let-23(+), and others lacked it. Three of the six vulval precursor cells are derived from AB.pl and three are derived from AB.pr. We identified 16 mosaic animals in which the let-23(+) ncl-1(+) extrachromosomal array had been lost in either AB.pl or AB.pr (or later in the AB.pr/l lineages) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mosaic analysis of let-23 in let-23(syl); gap-1(ga133) mutants

| Row

|

Loss ata

|

P3.p

|

P4.p

|

P5.p

|

P6.p

|

P7.p

|

P8.p

|

Vulva

|

No.b

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | no loss | 3° | 3° | 2° | 1° | 2° | 3° | normal | manyc |

|

|

|||||||||

| 2 | AB.pl, AB.pr | 3° | 3° | 2° | 1° | 2° | 3° | normal | 5 |

|

|

|||||||||

| 3 | AB.pl, ⩾ AB.pr | 3° | 3° | 2° | 1° | 2° | 3° | normal | 3 |

|

|

|||||||||

| 4 | >AB.pl | 3° | 3° | 2° | 1° | 2° | 3° | normal | 1 |

| 5 | AB.pl | 3° | 3° | 2° | 1° | 2° | 3° | normal | 1 |

| 6 | AB.pl, > AB.pr | 3° | 2° | 1° | 2° | 3° | 3° | normal | 4 |

| 7 | AB.pr | 3° | 2° | 1° | 2° | 3° | 3° | normal | 2 |

Pattern of cell fates expressed in mosaic animals. Cell fates were assigned as described in Table 2 and in Materials and Methods. Bold numbers indicate cells that were non-Ncl and thus expressed let-23(+); plain numbers indicate cells that were Ncl and thus lacked let-23(+). The cells that generated vulval tissue are underlined.

The extrachromosomal array (gaEx37) was lost at the indicated cell division or, as indicated by >, at a later division. ⩾AB.pr (row 3) refers to one animal in which the loss had occurred in AB.pr or at a later division.

Number of mosaic animals identified.

Data from Sulston and Horvitz (1977).

First, in the five animals shown in row 2 of Table 3, P4.p, P5.p, and P8.p lacked let-23(+), whereas P6.p and P7.p expressed let-23(+). In these mosaic animals, P4.p and P8.p adopted the 3° cell fate instead of induced (1° or 2°) vulval cell fates. The most likely explanation is that let-23(+) activity in the vulval precursor cells near the anchor cell (P6.p and P7.p in these examples) inhibited the expression of vulval cell fates by P4.p and P8.p. Second, the results from the four mosaic animals shown in rows 3 and 4 of Table 3 suggest that expression of let-23(+) in P6.p is sufficient to inhibit P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p from adopting induced (1° or 2°) vulval cell fates. These animals expressed let-23(+) in P6.p but lacked let-23(+) in P5.p or P7.p. In these animals, P3.p or P4.p lacked let-23(+) and adopted the 3° uninduced cell fate, likely the result of inhibition by let-23(+) in P6.p. Finally, in the seven animals shown in rows 5–7 of Table 3, P6.p lacked let-23(+), whereas P5.p expressed let-23(+). In six of these seven cases, P5.p adopted the 1° cell fate, and adjacent cells (P4.p and P6.p) adopted the 2° cell fate (probably as the result of the lateral signal from P5.p). In these animals, P3.p or P7.p lacked let-23(+) activity and expressed the 3° cell fate. This result suggests that let-23(+) in P5.p may have prevented induction of vulval cell fates in P3.p and P7.p.

In summary, all 16 mosaic animals exhibited a non-Muv phenotype. Among these animals, there were 25 examples in which either P3.p, P4.p, or P8.p lacked let-23(+) and gap-1(+) activity, and these cells expressed the uninduced 3° cell fate in all cases. In contrast, in non-mosaic let-23(sy1); gap-1(ga133) animals, P3.p, P4.p, or P8.p expressed an induced (1° or 2°) vulval cell fate in 7 of 15 cases, and 73% of these double mutants exhibit a Muv phenotype (Tables 1 and 2D). These findings suggest that let-23 prevents vulval induction in a cell-nonautonomous fashion. Expression of let-23(+) in the vulval precursor cell closest to the inducing anchor cell (P6.p) may prevent induction of the vulval precursor cells further away from the anchor cell (P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p).

gap-1 inhibits let-60 ras signaling in multiple tissues

The let-60 ras pathway is required for multiple aspects of C. elegans development, including vulval induction (Beitel et al. 1990; Han and Sternberg 1990). Therefore, we examined if gap-1 inhibits the activity of the let-60 ras pathway in other cell types beside the vulval precursor cells. In addition to defects in vulval induction, loss-of-function mutations in the let-60 ras pathway result in rod-like lethality at the first larval stage, sterility caused by defects in oocyte maturation, defects in the specification of the P12.p cell fate in the posterior ectoderm of the hermaphrodite, and defective spicules in the male tail.

Similar to our approach for vulval induction, we examined whether gap-1(ga133) suppresses defects caused by mutations that partially decrease the activity of the let-60 ras signaling pathway in these tissues. We were unable to use let-60(n1876) in these experiments because this allele exhibits maternal effect lethality. In homozygous mutants segregated from heterozygous parents, maternal let-60(+) activity rescues all of the let-60 phenotypes except for vulval defects, and in homozygous mutant animals segregated from homozygous parents, lethality prevents observation of all other phenotypes occurring later in development. Instead of using a let-60 ras allele, we examined partial reduction-of-function mutations in let-23 and mpk-1. These genes likely act in the same pathway as let-60 ras as they exhibit many mutant phenotypes similar to let-60 ras mutants and certain reduction-of-function mutations in these genes are partially viable, allowing us to score defects in all tissues that require the let-23/let-60/mpk-1 signaling pathway (Aroian and Sternberg 1991; M. Lackner, pers. comm.). We found that gap-1(ga133) suppresses larval lethality, defects in the posterior ectoderm of the hermaphrodite (P12.p) and spicule defects in the male tail caused by let-23(sy10) as well as sterility in mpk-1(ga111) mutants (M. Lackner, unpubl.) (Table 4). In summary, these results suggest that gap-1 may interact with let-60 ras in all tissues known to respond to the let-60 ras signaling pathway.

Table 4.

gap-1 activity in different tissues

|

|

let-23

|

let-23; gap-1

|

|---|---|---|

| Vulval induction | 11 ± 10 (36) | 100 (35) |

| Viabilitya | 10 ± 5 (134) | 51 ± 8 (140) |

| P12.pb | 74 ± 14 (35) | 91 ± 7 (23) |

| Male tail | 5 ± 9 (21) | 70 ± 19 (23) |

| Fertilityc | 0 (36) | 0 (35) |

| mpk-1d | mpk-1; gap-1d | |

| Fertilityc | 0 (>30) | 100 (30) |

The percentage of animals (±95% confidence interval) that exhibited wild-type development of the respective tissues are indicated; numbers in brackets refer to the number of animals analyzed. Alleles used: let-23(sy10), gap-1(ga133) and mpk-1(ga111). mpk-1(ga111) is a partial reduction-of-function mutation that exhibits a 100% sterile phenotype at 25°C (M. Lackner, unpubl.).

Viability was measured by counting the number of the entire Unc non-Dpy (Dumpy) and non-Unc non-Dpy progeny segregated from single unc-4(e120) let-23(sy10)/mnC1[dpy-10(e128) unc-52(e444)] and unc-4(e120) let-23(sy10)/mnC1[dpy-10(e128) unc-52(e444)]; gap-1(ga133) hermaphrodites. We calculated the percent viability (v) as v = 200* (no. Unc non-Dpy/no. non-Unc non-Dpy).

Differentiation of P12.p and male tail development were scored at the L4 stage and in young adults, respectively, as described (Aroian and Sternberg 1991).

let-23 appears to be required for a different aspect of oocyte maturation from let-60, as let-23 mutations block the maturation of oocytes at a step after the pachytene arrest observed in let-60 ras mutants (J. McCarter and T. Schedl, pers. comm.). We found that gap-1(ga133) does not suppress the oocyte maturation defect caused by let-23(sy10) (Table 4). Thus, an increase in let-60 activity caused by gap-1(ga133) might not compensate for the sterility caused by mutations in let-23. This result further confirms that let-23 EGFR might activate a signaling pathway in the gonad that does not require let-60 ras function.

Discussion

We have investigated two distinct mechanisms of inhibition of vulval induction. One mechanism is mediated by GAP-1 and another one is mediated by the receptor tyrosine kinase LET-23.

Inhibition by GAP-1

We have identified gap-1 in a genetic screen for inhibitors of vulval induction. Loss-of-function mutations in gap-1 suppress the Vul phenotype caused by reduction-of-function mutations in several genes that act in the anchor cell signaling pathway, including lin-3 EGF, let-23 EGFR, sem-5 GRB2, and let-60 ras.

gap-1 may inhibit let-60 ras in most, if not all, tissues that normally respond to let-60 ras signaling. In addition to the vulval precursor cells, let-60 acts during early larval development, in the posterior ectoderm of the hermaphrodite (P12.p), during oocyte maturation and male tail development (Beitel et al. 1990; Han and Sternberg 1990; Aroian and Sternberg 1991). We found that gap-1(ga133) can suppress defects in each of these tissues caused by partial reduction-of-function mutations in let-23 EGFR or mpk-1, two genes that act in the let-60 ras pathway (Aroian and Sternberg 1991; Lackner et al. 1994).

gap-1 encodes a protein similar to Drosophila Gap-1 and mammalian Gap-1m (Gaul et al. 1992; Maekawa et al. 1994; Baba et al. 1995). Biochemical analysis has indicated that human Gap-1m can stimulate the GTPase activity of Ras proteins (Maekawa et al. 1994), suggesting that C. elegans GAP-1 most likely functions to inhibit vulval induction by stimulating the GTPase activity of LET-60 Ras (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Models for inhibition by GAP-1 and LET-23. (A) GAP-1 inhibits signaling through LET-60 Ras by stimulating the GTPase activity of LET-60 Ras. GNEF refers to a hypothetical guanine nucleotide exchange factor that stimulates the release of GDP from LET-60 Ras in response to a signal from LET-23 EGFR. (B) LET-23 in P6.p sequesters the anchor cell signal LIN-3 EGF, thereby preventing induction of P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p. In let-23(sy1) mutants, LIN-3 EGF may not be sequestered by P6.p, and unbound LIN-3 EGF might diffuse further away from the anchor cell. The gap-1(ga133) mutation allows vulval precursor cells to respond to lower levels of LIN-3 EGF than wild-type cells. In let-23(sy1); gap-1(ga133) double mutants, P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p are exposed to low levels of LIN-3 and can express vulval cell fates. (○) LIN-3 EGF molecules; (Y) LET-23 EGFR; (I) 1°, 2° or hybrid 1°/2° cell fates.

Genetic analysis in Drosophila, yeast, and mammals has suggested that RasGAPs function as inhibitors of the Ras pathway (Boguski and McCormick 1993; Henkemeyer et al. 1995). During eye development in Drosophila, a signal from the R8 cell induces R7 to differentiate into a neuronal photoreceptor cell by activating the sevenless receptor tyrosine kinase/ras/rolled MAP kinase pathway. Loss-of-function mutations in Drosophila Gap-1 bypass the requirement for a signal from sevenless and result in the generation of excess R7 cells, similar to the phenotype caused by constitutive activation of Ras (Gaul et al. 1992). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Ira1 and Ira2 encode GAPs that function as negative regulators of RAS1 and RAS2 in the cyclic AMP pathway. In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Sar1/gap-1 encodes a GAP that inhibits Ras1 in the pheromone response pathway. Mutations in Ira1, Ira2, or Sar1/gap-1 result in constitutive activation of the corresponding Ras pathways (for review, see Boguski and McCormick 1993). Vascularization in mammals is likely controlled by a Ras signaling pathway acting downstream of the VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase. A loss-of-function mutation in the gene encoding mouse p120 RasGAP results in embryonic lethality as a result of defective vascularization. One possibility is that Ras might be hyperactivated in these mutants, although another possibility is that lethality might be caused by defects in a p120 effector function (Henkemeyer et al. 1995).

It has also been proposed that some RasGAPs (p100 and p120 RasGAP) may act as effector molecules downstream of Ras (Medema et al. 1992; Duchesne et al. 1993). It is unlikely, however, that C. elegans GAP-1 acts as an effector downstream of LET-60 Ras because GAP-1 lacks SH2 and SH3 domains, and these domains are required for the effector function of p100 and p120 RasGAPs. Also, none of our genetic experiments suggests such an effector function for gap-1. In particular, mutations in downstream effectors of let-60 ras (such as lin-45 raf, mek-2, or mpk-1) can suppress the Muv phenotype caused by constitutive activation of let-60 ras (Han et al. 1993; Lackner et al. 1994; Wu and Han 1994; Kornfeld et al. 1995; Wu et al. 1995). Mutations in gap-1, however, do not exhibit this suppressor phenotype (Eisenmann and Kim 1997 and data not shown).

In contrast to yeast, Drosophila, and mice, null mutations in C. elegans gap-1 do not result in constitutive activation of the Ras signaling pathway because gap-1 mutants do not exhibit a Muv phenotype. One possible explanation for this difference is that in C. elegans, gap-1 function might be redundant with another RasGAP gene. The C. elegans genome project has recently sequenced a gene that is predicted to encode another GAP (similar to vertebrate p120 RasGAP). Loss-of-function mutations in both GAP genes might eliminate all GAP activity and result in a Muv phenotype. Another possibility is that other types of inhibitory genes such as the synthetic multivulva genes (Ferguson and Horvitz 1989), sli-1 (Yoon et al. 1995) or any of the other genes identified in the lin-10 suppressor screen might act in parallel to gap-1 to repress vulval induction.

In summary, these results extend previous results showing that the central molecular components of the Ras signaling pathway are conserved in metazoans. Genetic analysis in C. elegans has now identified nine conserved signaling genes in this pathway (lin-3, let-23, sem-5, let-60, gap-1, lin-45, mek-2, mpk-1, and ksr-1; for review, see Kornfeld 1997). Here, we have shown that C. elegans gap-1 has a function similar to RasGAPs from other organisms and inhibits Ras signaling pathways in multiple tissues.

Antagonistic function of LET-23 EGFR

LET-23 EGFR performs at least two functions during vulval induction. One function is to induce vulval cell fates by activating the LET-60 Ras pathway, and another function is to prevent excess vulval induction. Certain mutations in lin-2, lin-7, lin-10, or let-23 do not eliminate the activating function of let-23 (so that vulval precursor cells can still respond to the anchor cell signal), but these mutations strongly reduce the inhibitory function of let-23 and cause excess vulval induction (Ferguson and Horvitz 1985; Aroian and Sternberg 1991; R. Hoskins, pers. comm.).

Using mosaic analysis, we have found that let-23 prevents vulval induction in a cell-nonautonomous fashion. Specifically, our data indicate that wild-type LET-23 EGFR in the vulval precursor cell closest to the anchor cell (P6.p) may prevent induction of vulval precursor cells that are further away from the anchor cell (P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p). Our results, however, do not exclude the possibility that let-23 might also inhibit vulval induction in a cell-autonomous fashion and that excess vulval induction may only be observed if let-23 inhibitory activity is absent in both the distal Pn.p cells (P3.p, P4.p, or P8.p) as well as in the inhibitory cell (P6.p).

How might LET-23 EGFR mediate this cell-nonautonomous inhibitory function? One possible mechanism that is most consistent with our data is that LET-23 EGFR in P6.p might bind and sequester the inductive signal LIN-3 EGF so that P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p may not be exposed to significant amounts of the inductive signal (Fig. 5B). Activation of LET-23 EGFR by the anchor cell signal leads to an increase in LET-23 expression in P6.p (Simske et al. 1996 and pers. comm.), which might serve to enhance ligand sequestering by P6.p. Mutations that partially reduce the activity of LET-23 EGFR (such as mutations in lin-2, lin-7, lin-10, or let-23) might decrease the amount of LIN-3 EGF that is bound by P5.p, P6.p, and P7.p, and unbound LIN-3 EGF might be free to diffuse further away from the anchor cell to induce all six vulval precursor cells. Free LIN-3 EGF might cause a strong Muv phenotype in gap-1 mutants because loss of gap-1 function allows the vulval precursor cells to adopt vulval cell fates in response to low levels of the inductive signal.

According to the ligand sequestering model, the range over which LIN-3 can act should be limited by expression of LET-23 on the proximal vulval precursor cells (such as P6.p). If so, then overexpression of LIN-3 might increase the levels of LIN-3 over those of LET-23, so that enough LIN-3 might remain unbound to freely diffuse to distal vulval precursor cells (P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p). In support of this idea, overexpression of LIN-3 from a multicopy array causes a Muv phenotype (Hill and Sternberg 1992).

Another prediction of the ligand-sequestering model is that the inhibitory activity of LET-23 should require the extracellular domain that binds to LIN-3, but might not require the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain. We tested this prediction by analyzing the effects of mutations in the ligand-binding site and in the tyrosine kinase domain on the inhibitory activity of let-23 in transformation rescue experiments. We observed that expression of a transgene with the mn23 mutation (encoding a LET-23 protein with a defective ligand-binding domain (Aroian et al. 1993) did not exhibit any inhibitory activity when injected into let-23(sy1); gap-1(ga133) animals in transformation rescue experiments (data not shown). This result indicates that the putative LIN-3-binding domain is essential for inhibitory activity. In contrast, a transgene with the sy5 mutation (encoding a LET-23 protein containing a defective tyrosine kinase domain (Aroian et al. 1993) had partial inhibitory activity when injected into let-23(sy1); gap-1(ga133) animals (data not shown). High levels of expression of let-23(sy5) appear to be toxic (A. Hajnal, unpubl.), so that surviving transgenic let-23(sy5) animals may show only partial inhibition because of low levels of let-23(sy5) expression. Alternatively, this result might indicate that the tyrosine kinase domain is partially required for the inhibitory function.

Sequestering extracellular signaling molecules by transmembrane receptors might be a common mechanism that is used to restrict the action of secreted signals to a small field of cells and to prevent induction of cells located distally. For example, the C. elegans LIN-12 receptor is activated in the presumptive ventral uterine cell by the LAG-2 ligand from the anchor cell. Expression of LAG-2 by the anchor cell can potentially induce nearby gametes to undergo mitotic divisions, but LIN-12 on the ventral uterine cells prevents this abnormal induction by binding and sequestering it (Seydoux et al. 1990). In Drosophila, the Trunk extracellular ligand activates the Torso receptor to specify the posterior and anterior poles of the embryo. If Torso is absent from the end poles, more central regions of the embryo respond to the Trunk signal, suggesting that Torso at the poles of the embryo might sequester Trunk (Casanova and Struhl 1993). Similar mechanisms may occur during dorsoventral patterning of the Drosophila embryo in which the Toll receptor appears to prevent diffusion of its ligand Spaetzle into the perivitelline fluid (Stein et al. 1991), and during patterning of the wing discs in which the Patched receptor may limit the range of the Hedgehog signal by binding and sequestering it (Chen and Struhl 1996).

Materials and methods

General methods and strains

C. elegans strains were cultured as described (Brenner 1974) and were grown at 20°C unless noted otherwise. Wild-type refers to C. elegans variety Bristol, strain N2. For the RFLP studies, we used C. elegans variety Bergerac (B0) and C. elegans variety CB4000. Unless noted otherwise, the mutations used in this study have been described in Wood (1988) and are listed below. LGI: lin-10(n1299, n1390) (Kim and Horvitz 1990), unc-29(e1072); LGII: unc-4(e120), let-23(mn23, sy1, sy10) (Aroian et al. 1993), lin-7(e1449) (Simske et al. 1996), the balancer mnC1[dpy-10(e128) unc-52(e444)]; LGIII: ncl-1(e1942), unc-32(e189), lin-36(n766); LGIV: unc-5(e53), lin-45(n2018) (Han et al. 1993), lin-3(e1417), let-60(n1876) (Beitel et al. 1990), dpy-20(e1302), unc-22(e66), unc-30(e191); LGV: him-5(e1490); LGX: unc-1(e1598n1201), gap-1(n1329) (Kim and Horvitz 1990), gap-1(n1667, n1672, n1683, n1683, n1691, n1701, ga4, ga12, ga14, ga33, and ga133) (this study), dpy-3(e27), unc-2(e55), lon-2(e678), sem-5(n2019) (Clark et al. 1992), lin-2(n1610, n397) (Hoskins et al. 1996), unc-9(e101), lin-15(n765).

Genetic screens

lin-10(n1390) or lin-2(n1610) animals were mutagenized at the L4 larval stage with either ethyl methanesulfonate or psoralen as described (Edgar and Hirsh 1985; Wood 1988). Mutagenized parents were individually placed onto 10 cm NGM-plates, or 10–15 F1 animals were placed onto 6 cm plates. We either isolated rare F2 animals that were non-Vul, or we picked eggs laid by F2 animals from plates that contained many eggs. Animals that continued to segregate >90% non-Vul progeny were back crossed at least three times before they were analyzed further. After screening 150,000 EMS-mutagenized haploid genomes of lin-10(n1390) or lin-2(n1610) animals and 30,000 psoralen-mutagenized haploid genomes of lin-10(n1390) animals, we isolated over 60 independent suppressor mutations. The mutation gap-1(n1329) had been identified previously as an extragenic suppressor of lin-10(n1299) (Kim and Horvitz 1990), and gap-1 was previously known as suv-1 (suppressor of vulvaless). For each suppressor mutation, complementation tests were done by mating of lin-10(n1390) males containing the suppressor mutation with lin-10(n1390); unc-1(e1598n1201) gap-1(n1329) lon-2(e678) hermaphrodites. Non-Unc, non-Lon cross progeny were examined to determine whether they were suppressed for the lin-10(n1390) Vul phenotype. n1667, n1672, n1683, n1691, n1701, ga4, ga12, ga14, ga33, ga34, and ga133 failed to complement the suppressor phenotype of gap-1(n1329).

RFLP mapping

Three-factor crosses between gap-1 and unc-1, unc-2, or dpy-3 were performed as described (Wood 1988) to establish the relative map position of gap-1 shown in Figure 1A. The RFLP gaP21 was identified by Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA of the wild-type strains N2 and B0 cut with HindIII, with the cosmid R02C5 as probe. The RFLP pkP670 is caused by a Tc1 transposon insertion in the strain CB4000 into a region covered by the cosmid F48B9 (R. Korswagen, pers. comm.) and can be detected by a PCR assay with the oligonucleotide primers pkP670 and RIIL (Table 5). We constructed lin-10(n1390); unc-1 gap-1(n1329) lon-2(e678)/BO or CB4000 heterozygotes and lin-10(n1390); gap-1(n1329) unc-2(e55)/BO or CB4000 heterozygotes and mapped the gaP21 and pkP670 physical markers located on the Bergerac or CB4000 chromosome relative to the unc-1, gap-1, and unc-2 genetic markers located on the Bristol chromosome. These experiments indicated the following genetic map order (brackets indicate the number of recombinants between two markers): unc-1 [18] gaP21 [4] gap-1 [0] pkP670 [26] unc-2.

Table 5.

Sequences of oligonucleotide primers

| Name

|

Sequence (5′ → 3′)

|

|---|---|

| pk670 | CCGTTACATCACTTCAATCT |

| RIIL | GATTTTGTGAACACTGTGGTGAAG |

| S1A | CTGATAAGTTTGTTTTCTCCGC |

| S1B | CCCTTCTGATAGTGAGTACG |

| S1C | CTGTTATCCCCTATTTTAGTGG |

| S1D | CTCTTGCTGGATCCACTTCAC |

| S1E | CTGTAGTGGATAAGGTAAGTCG |

| S1F | ACCTTCGATGATAATGGTCC |

| S1G | GTCTAACTGTAGTGTCAGTG |

| S1H | CAGTCAGTTGCTTCTACACC |

| S1I | GCTGCAATTTGAAGCTCCCG |

| S1K | CATTCCGCCGGAGCTTCTTC |

| S1L | AAGGCAAAAGTGGCTCGTCCTGTG |

| S1M | TTGAGGGGGTATGGCATAAGTCTGG |

| S1O | CCATTCAATCATTGTCTCGCGCGG |

| S1P | GTGAAGTGGATCCAGCAAGAG |

| T24C12+ | CCATCCAGCCGAGTTGATTGTCAC |

| T24C12− | AATAACCGACCCGTCGGATGTCAC |

Identification of gap-1 polymorphisms

To map the DNA rearrangements in gap-1(n1329) and gap-1(ga133) animals, we used the oligonucleotide primers T24C12.2+ and T24C12.2− to amplify a 4.6-kb genomic DNA fragment from mutants (Table 5), subcloned BglII-digested fragments containing the rearrangements into pCRII (Invitrogen) and determined their sequence. Comparison to the wild-type sequence determined by the C. elegans genome sequencing project showed that gap-1(n1329) contains an insertion of a Tc1 transposon at nucleotide position 389 and that gap-1(ga133) contains a deletion between nucleotide positions 485 and 717 (Fig. 2).

To search for point mutations in mutants carrying the gap-1 alleles n1683, n1691, n1701, ga4, ga12, and ga14, we amplified the entire coding region from wild-type and mutant genomic DNA in small overlapping fragments using PCR. We used the oligonucleotides S1A and S1B to amplify a 562-bp fragment spanning exons 1 and 2, S1C and S1D to amplify a 490-bp fragment spanning exons 3 and 4, S1E and S1F to amplify a 513-bp fragment spanning exon 5 and most of exon 6, S1G and S1H to amplify a 516-bp fragment spanning the remainder of exon 6, exon 7, and most of exon 8, and S1I and S1K to amplify a 561-bp fragment spanning the rest of exon 8, exons 9 and 10 (Table 5). Mutations in the PCR products were detected by single-stranded conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis as described (Hoskins et al. 1996) for four alleles (n1683, n1691, ga12, ga14). DNA fragments displaying polymorphisms were directly sequenced on both strands, and the mutant sequences were compared with the sequence of the wild-type gap-1 locus. The remaining two alleles, ga4 and n1701, may contain point mutations that were not detected by the SSCP analysis.

RT–PCR amplification of gap-1 cDNA

RNA was prepared from mixed stage wild-type animals, and ∼1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with Moloney murine leukemia virus (Mo-MuLV) reverse transcriptase and the gap-1 primer S1K (Table 5). cDNA was amplified by use of PCR with the oligonucleotide primers S1A and S1D to yield a single 796-bp product spanning exons 1–5 and with the oligonucleotide primers S1O and S1P to yield a single 899-bp product spanning exons 6–10, suggesting the existence of a single splice form of gap-1 mRNA (Table 5). The PCR products were sequenced to confirm the splicing pattern shown in Figure 1B.

Germ-line transformation

Germ-line transformation experiments were performed by microinjection of DNA into the gonads of unc-29(e1072); gap-1(ga133) lin-2(n397) animals with unc-29(+) as a cotransformation marker (cosmid F35D3) by standard methods (Mello et al. 1991). We used PCR amplification with the oligonucleotide primers S1L and S1M (Table 5) to obtain a 9.7-kb genomic fragment containing the wild-type gap-1 gene; this fragment includes 5 kb of 5′-flanking sequences upstream of the start codon, 3.7 kb between the start and stop codons and 1 kb of 3′-flanking sequences downstream of the stop codon. The same oligonucleotide primers were used to amplify a 9.4-kb genomic fragment from gap-1(ga133) genomic DNA under identical conditions. gap-1 DNA was injected at a concentration of 100 μg/ml together with 50 μg/ml unc-29(+) cosmid DNA. In the strains transformed with wild-type gap-1 DNA, between 30% and 72% of the non-Unc transformants exhibited a Vul non-Muv phenotype similar to lin-2(n397) single mutants (three lines). In strains transformed with mutant gap-1(ga133) DNA, <8% of the transformants were Vul non-Muv (three lines).

Genetic analysis

To construct double and triple mutant strains between gap-1 and other genes that control vulval induction, we used the null mutation ga133 because it can be detected by amplification of genomic DNA from single animals with the oligonucleotide primers S1C and S1D (Table 5). DNA amplified from gap-1(ga133) animals yields a 156-bp product, DNA amplified from gap-1(+) animals yields a 490-bp product, and DNA amplified from gap-1(ga133)/+ animals yields both products. A strain was judged to be homozygous for gap-1(ga133) if at least 20 randomly picked animals were homozygous as determined by the PCR assay described above.

Lineage analysis and anchor cell ablations

Pn.p cell lineages were determined by use of Nomarski optics, as described previously (Sternberg and Horvitz 1986). Differentiation of P12.p and of the male tail were scored at the L4 larval stage and in young adults, respectively, as described previously (Aroian and Sternberg 1991).

The anchor cell was removed by ablation of the precursors of the somatic gonad, Z1 and Z4, during the L1 larval stage with a laser microbeam, as described (Kimble 1981).

Mosaic analysis

The extrachromosomal array gaEx37 carries unc-29(+), let-23(+), ncl-1(+), and unc-30(+) (Simske and Kim 1995), and >95% of unc-29(e1072); let-23(sy1); ncl-1(e1942); unc-30(e191); gap-1(ga133); gaEx37 animals exhibit a non-Unc non-Ncl non-Muv phenotype. Mosaic animals were identified and scored as described previously (Hoskins et al. 1996; Miller et al. 1996). For 13 of 16 mosaic animals presented in Table 3, we inferred the vulval lineage of each Pn.p cell without directly observing the pattern of cell division because the animals had the correct number, position, and morphology of vulval cell nuclei when viewed at the L4 larval stage, subsequently developed a functional vulva, and were non-Muv as adults. We directly observed the Pn.p cell lineages for the three remaining animals (two in Table 3, row 2, and one in row 7).

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne Villeneuve for help with the initial three-factor crosses to map gap-1, Rik Korswagen for providing sequence information about the polymorphism pkP670, Diane Parry and Suzanne Driscoll for providing gap-1 alleles, Al Candia, Dave Eisenmann, Sue Kaech, Mark Lackner and Patrick Tan for critical reading of the manuscript and all members of the laboratory for stimulating discussions. This work was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Swiss National Foundation to A.H. and by a grant to S.K.K. from the National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL kim@cmgm.stanford.edu; FAX (415) 725-7739.

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian RV, Sternberg PW. Multiple functions of let-23, a Caenorhabditis elegans receptor tyrosine kinase gene required for vulval induction. Genetics. 1991;128:251–267. doi: 10.1093/genetics/128.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian RV, Koga M, Mendel JE, Ohshima Y, Sternberg PW. The let-23 gene necessary for Caenorhabditis elegans vulval induction encodes a tyrosine kinase of the EGF receptor subfamily. Nature. 1990;348:693–699. doi: 10.1038/348693a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroian RV, Lesa GM, Sternberg PW. Mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans let-23 EGFR-like gene define elements important for cell-type specificity and function. EMBO J. 1993;12:360–366. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba H, Fuss B, Urano J, Poullet P, Watson JB, Tamanoi F, Macklin WB. GapIII, a new brain-enriched member of the GTPase-activating protein family. J Neurosci Res. 1995;41:846–858. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490410615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitel GJ, Clark SG, Horvitz HR. Caenorhabditis elegans ras gene let-60 acts as a switch in the pathway of vulval induction. Nature. 1990;348:503–509. doi: 10.1038/348503a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boguski MS, McCormick F. Proteins regulating Ras and its relatives. Nature. 1993;366:643–654. doi: 10.1038/366643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag G, McCormick F. Regulators and effectors of Ras proteins. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1991;7:601–632. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.003125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova J, Struhl G. The torso receptor localizes as well as transduces the spatial signal specifying terminal body pattern in Drosophila. Nature. 1993;362:152–155. doi: 10.1038/362152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Struhl G. Dual roles for patched in sequestering and transducing hedgehog. Cell. 1996;87:553–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SG, Stern MJ, Horvitz HR. C. elegans cell-signalling gene sem-5 encodes a protein with SH2 and SH3 domains. Nature. 1992;356:340–344. doi: 10.1038/356340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SG, Lu X, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans locus lin-15, a negative regulator of a tyrosine kinase signaling pathway, encodes two different proteins. Genetics. 1994;137:987–997. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.4.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne M, Schweighoffer F, Parker F, Clerc F, Frobert Y, Thang MN, Tocque B. Identification of the SH3 domain of GAP as an essential sequence for Ras-GAP-mediated signaling. Science. 1993;259:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.7678707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar LG, Hirsh D. Use of a psoralen-induced phenocopy to study genes controlling spermatogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1985;111:108–118. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, D. and S. Kim. 1997. Mechanism of activation of the C. elegans ras homolog let-60 by a novel, temperature-sensitive, gain-of-function mutation. Genetics (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Favello A, Hillier L, Wilson RK. Genomic DNA sequencing methods. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;48:551–569. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61403-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson EL, Horvitz HR. Identification and characterization of 22 genes that affect the vulval cell lineages of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1985;110:17–72. doi: 10.1093/genetics/110.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— The multivulva phenotype of certain Caenorhabditis elegans mutants results from defects in two functionally redundant pathways. Genetics. 1989;123:109–121. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaul U, Mardon G, Rubin GM. A putative Ras GTPase activating protein acts as a negative regulator of signaling by the Sevenless receptor tyrosine kinase. Cell. 1992;68:1007–1019. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90073-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Sternberg PW. let-60, a gene that specifies cell fates during C. elegans vulval induction, encodes a ras protein. Cell. 1990;63:921–931. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90495-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Aroian RV, Sternberg PW. The let-60 locus controls the switch between vulval and nonvulval cell fates in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1990;126:899–913. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.4.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Golden A, Han Y, Sternberg PW. C. elegans lin-45 raf gene participates in let-60 ras-stimulated vulval differentiation. Nature. 1993;363:133–140. doi: 10.1038/363133a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock EM, Herman RK. The ncl-1 gene and genetic mosaics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;141:989–1006. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.3.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkemeyer M, Rossi DJ, Holmyard DP, Puri MC, Mbamalu G, Harpal K, Shih TS, Jacks T, Pawson T. Vascular system defects and neuronal apoptosis in mice lacking ras GTPase-activating protein. Nature. 1995;377:695–701. doi: 10.1038/377695a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman RK, Hedgecock EM. Limitation of the size of the vulval primordium of Caenorhabditis elegans by lin-15 expression in surrounding hypodermis. Nature. 1990;348:169–171. doi: 10.1038/348169a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DG, Sharp PM. CLUSTAL: A package for performing multiple sequence alignments on a microcomputer. Gene. 1988;73:237–244. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RJ, Sternberg PW. The gene lin-3 encodes an inductive signal for vulval development in C. elegans. Nature. 1992;358:470–476. doi: 10.1038/358470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz HR, Sulston JE. Isolation and genetic characterization of cell-lineage mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1980;96:435–454. doi: 10.1093/genetics/96.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins R, Hajnal AF, Harp SA, Kim SK. The C. elegans vulval induction gene lin-2 encodes a member of the MAGUK family of cell junction proteins. Development. 1996;122:97–111. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LS, Tzou P, Sternberg PW. The lin-15 locus encodes two negative regulators of Caenorhabditis elegans vulval development. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:395–411. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.4.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz WS, Hill RJ, Clandinin TR, Sternberg PW. Different levels of the C. elegans growth factor LIN-3 promote distinct vulval precursor fates. Cell. 1995;82:297–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene lin-10 is broadly expressed while required specifically for the determination of vulval cell fates. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:357–371. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble J. Alterations in cell lineage following laser ablation of cells in the somatic gonad of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1981;87:286–300. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga M, Ohshima Y. Mosaic analysis of the let-23 gene function in vulval induction of Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1995;121:2655–2666. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld K. Vulval development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Genet. 1997;13:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld K, Guan KL, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene mek-2 is required for vulval induction and encodes a protein similar to the protein kinase MEK. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:756–768. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner MR, Kornfeld K, Miller LM, Horvitz HR, Kim SK. A MAP kinase homolog, mpk-1, is involved in ras-mediated induction of vulval cell fates in C. elegans. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:160–173. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Jongeward GD, Sternberg PW. unc-101, a gene required for many aspects of Caenorhabditis elegans development and behavior, encodes a clathrin-associated protein. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:60–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein EJ, Daly RJ, Batzer AG, Li W, Margolis B, Lammers R, Ullrich A, Skolnik EY, Bar SD, Schlessinger J. The SH2 and SH3 domain-containing protein GRB2 links receptor tyrosine kinases to ras signaling. Cell. 1992;70:431–442. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90167-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa M, Li S, Iwamatsu A, Morishita T, Yokota K, Imai Y, Kohsaka S, Nakamura S, Hattori S. A novel mammalian Ras GTPase-activating protein which has phospholipid-binding and Btk homology regions. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6879–6885. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medema RH, de Laat LW, Martin GA, McCormick F, Bos JL. GTPase-activating protein SH2-SH3 domains induce gene expression in a Ras-dependent fashion. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3425–3430. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC, Kramer JM, Stinchcomb D, Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C.elegans: Extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:3959–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LM, Waring DA, Kim SK. Mosaic analysis using a ncl-1(+) extrachromosomal array reveals that lin-31 acts in the Pn.p cells during Caenorhabditis elegans vulval development. Genetics. 1996;143:1181–1191. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.3.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier JP, Raabe T, Henkemeyer M, Dickson B, Mbamalu G, Margolis B, Schlessinger J, Hafen E, Pawson T. A Drosophila SH2–SH3 adaptor protein implicated in coupling the sevenless tyrosine kinase to an activator of Ras guanine nucleotide exchange, Sos. Cell. 1993;73:179–191. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90170-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffzek K, Lautwein A, Kabsch W, Reza Ahmadian M, Wittinghofer A. Crystal structure of the GTPase-activating domain of human p120GAP and implications for the interaction with Ras. Nature. 1996;384:591–596. doi: 10.1038/384591a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydoux G, Schedl T, Greenwald I. Cell-cell interactions prevent a potential inductive interaction between soma and germline in C. elegans. Cell. 1990;61:939–951. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90060-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MA, Dodson GS, Rubin GM. An SH3-SH2-SH3 protein is required for p21Ras1 activation and binds to sevenless and Sos proteins in vitro. Cell. 1993;73:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90169-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simske JS, Kim SK. Sequential signalling during Caenorhabditis elegans vulval induction. Nature. 1995;375:142–146. doi: 10.1038/375142a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simske JS, Kaech SM, Harp SA, Kim SK. LET-23 receptor localization by the cell junction protein LIN-7 during C. elegans vulval induction. Cell. 1996;85:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D, Roth S, Vogelsang E, Nüsslein-Volhard C. The polarity of the dorsoventral axis in the Drosophila embryo is defined by an extracellular signal. Cell. 1991;65:725–735. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg PW. Control of cell fates within equivalence groups in C. elegans. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:259–264. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg PW, Horvitz HR. Pattern formation during vulval development in C. elegans. Cell. 1986;44:761–772. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90842-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977;56:110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JH, Stern MJ, Horvitz HR. Cell interactions coordinate the development of the C. elegans egg-laying system. Cell. 1990;62:1041–1052. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90382-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood WB. The nematode caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Han M. Suppression of activated let-60 ras protein defines a role of Caenorhabditis elegans Sur-1 MAP kinase in vulval differentiation. Genes & Dev. 1994;8:147–159. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Han M, Guan KL. MEK-2, a Caenorhabditis elegans MAP kinase kinase, functions in Ras-mediated vulval induction and other developmental events. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:742–755. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon CH, Lee J, Jongeward GD, Sternberg PW. Similarity of sli-1, a regulator of vulval development in C. elegans, to the mammalian proto-oncogene c-cbl. Science. 1995;269:1102–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.7652556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]