Abstract

Inflammatory mechanisms influence tumor development and metastatic progression1. Of interest is the role of such mechanisms in metastatic spread of tumors whose etiology does not involve pre-existing inflammation or infection, such as breast and prostate cancers. We found that prostate cancer metastasis is associated with lymphocyte infiltration into advanced tumors and elevated expression of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family members receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) ligand (RANKL) and lymphotoxin (LT)2. But the source of RANKL and its role in metastasis were not established. RANKL and its receptor RANK control proliferation of mammary lobuloalveolar cells during pregnancy3 through activation of IκB kinase α (IKKα)4, a protein kinase that is required for self-renewal of mammary cancer progenitors5 and prostate cancer metastasis2. We therefore examined whether RANKL, RANK and IKKα are also involved in mammary/breast cancer metastasis. Indeed, RANK signaling in mammary carcinoma cells that overexpress the ErbB2 (c-Neu) proto-oncogene6, which is frequently amplified in metastatic human breast cancers7,8, was important for pulmonary metastasis. Metastatic spread of ErbB2-transformed carcinoma cells was also dependent on CD4+CD25+ T cells, whose major pro-metastatic function appeared to be RANKL production. RANKL-producing T cells were mainly FoxP3+ and found in close proximity to smooth muscle actin (SMA)-positive stromal cells in mouse and human breast cancers. The T cell-dependence of pulmonary metastasis was replaced by administration of exogenous RANKL, a procedure that also stimulated pulmonary metastasis of RANK-positive human breast carcinoma cells. These results are consistent with the adverse prognostic impact of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ or FoxP3+ T cells on human breast cancer9,10 and suggest that targeting of RANKL-RANK signaling can be used in conjunction with other therapies to prevent subsequent metastatic disease.

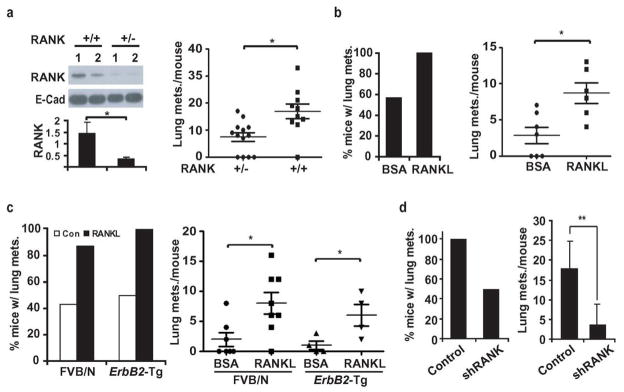

RANK signaling controls osteoclast maturation and bone resorption, and was therefore targeted to prevent bone metastasis in breast and prostate cancers11. A humanized RANKL antibody that reduces vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women and androgen-ablated prostate cancer patients was found to be a more potent inhibitor of bone metastasis than other osteoclast-targeting drugs12,13. To examine whether RANK signaling may control additional aspects of breast cancer metastasis, we used MMTV-ErbB2 transgenic mice of the FVB/N background6, in which mammary carcinomas are induced by a gene that is over-expressed in about 30% of human breast cancer7. Rank−/− mice are osteopetrotic, defective in tooth eruption, and exhibit retarded growth11. We therefore generated MMTV-ErbB2/Rank+/−/Fvb mice that were indistinguishable from MMTV-ErbB2/Rank+/+/Fvb mice in appearance, weight and general health. Although primary tumor development was not affected by reducing Rank gene dosage, mammary carcinomas from MMTV-ErbB2/Rank+/− mice expressed less RANK than MMTV-ErbB2/Rank+/+ tumors and the multiplicity of lung metastases was reduced by 50% (Fig. 1a). The role of RANK-signaling was further examined using an orthotopic tumor model in which primary mammary cancer cells (PCaM) from an MMTV-ErbB2 tumor were injected into the #2 mammary gland of FVB/N mice. Injection of recombinant RANKL, after inoculation, significantly increased the incidence and multiplicity of pulmonary metastases (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. RANK-signaling in mammary carcinoma cells enhances metastasis.

a, MMTV-ErbB2/Rank+/+/Fvb and MMTV-ErbB2/Rank+/−/Fvb mice were sacrificed 8 weeks after tumor onset. RANK expression in primary tumors was analyzed by immunoblotting (each lane a tumor from a different mouse, upper left) and quantitated by densitometry of relative to E-cadherin (bottom left; means +/− s.e.m.; n=6). Lung metastasis multiplicity was analyzed by H&E staining of lungs from MMTV-ErbB2/Rank+/+/Fvb (n=10) and MMTV-ErbB2/Rank+/−/Fvb (n=13) mice. Means +/− s.e.m. and data for individual mice are shown (right panel). b, PCaM cells from MMTV-ErbB2/Fvb mice were isolated and grafted (1×106 cells) into the #2 mammary glands of FVB/N mice subjected to twice weekly intra-tumoral injections of BSA or recombinant RANKL (80 μg/kg), starting one week post-inoculation. At day 35, lungs were isolated, sectioned, H&E stained, and metastatic lesions counted. Shown are means +/− s.e.m. (n=6) as well as values for individual mice. c, MT2 cells (1×106 ) were grafted into #2 mammary glands of FVB/N or MMTV-ErbB2/Fvb mice treated with BSA or RANKL and analyzed for pulmonary metastases as in a. Data are presented as incidence and multiplicity of pulmonary metastases (mean +/− s.e.m.; n=7–8). d, Mice were inoculated with 1×106 shRANK-transduced or control MT2 cells and lung metastases were measured 56 days later. Data are presented as incidence and multiplicity of pulmonary metastases (means +/− s.e.m.; n=6). *: P<0.05; **: P<0.01.

To facilitate mechanistic analysis, we generated an immortalized mammary carcinoma cell line, MT2, from an ErbB2-induced mammary tumor (Supplementary Fig. 1a). MT2 cells double every 24 hrs (Supplementary Fig. 1b), exhibit epithelial morphology in culture, form colonies in soft agar and mammospheres when grown in Petri dishes without serum (Supplementary Fig. 1c). MT2 cells expressed as much RANK as PCaM cells, but RANK expression was very low in non-transformed mammary epithelial cells (MEC) from tumor-free virgins (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Neither PCaM nor MT2 cells expressed Rankl mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 1e). MT2 cells underwent pulmonary metastasis after transplantation into the #2 mammary gland that was further enhanced by RANKL injection (Fig. 1c). To ascertain that the results of these experiments are not affected by a putative immune response elicited by the ErbB2-expressing cells, we transplanted MT2 cells into MMTV-ErbB2/Fvb mice that are tolerized to the ErbB2 oncogene14. The results were identical to those obtained in normal FVB/N mice (Fig. 1c). Silencing of RANK expression (Supplementary Fig. 1f) reduced pulmonary metastasis of MT2 cells (Fig. 1d) and blocked the response to RANKL(Supplementary Fig. 2a). Neither RANKL administration nor RANK silencing had a significant effect on primary tumorigenic growth of transplanted MT2 cells, which was identical in FVB/N and MMTV-ErbB2/Fvb mice (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c). Similar results were obtained by administration of a RANK-Fc fusion protein, which blocks RANK signaling15, into mice bearing MT2 mammary tumors. Whereas RANK-Fc marginally inhibited tumor growth at the primary site, it greatly reduced the incidence and multiplicity of pulmonary metastasis (Supplementary Fig. 3).

RANK signaling in MT2 cells induced nuclear translocation and phosphorylation of IKKα that was not associated with IKKβ and IKKγ/NEMO, the two other IKK complex components (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c), indicating that RANK signaling targets free IKKα or one that is part of a different complex. As in prostate cancer2, RANK-mediated IKKα activation repressed expression of the metastasis inhibitor maspin (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). Expression of ectopic maspin in MT2 cells (Supplementary Fig. 5d) marginally inhibited tumorigenic growth (Supplementary Fig. 5e), while strongly reducing pulmonary metastasis (Supplementary Fig. 5f). Maspin-MT2 tumors expressed nearly 4-fold more maspin than green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-marked MT2 tumors (Supplementary Fig. 5g). Exogenous RANKL treatment, which stimulated EGFP-MT2 metastatic activity and did not influence primary tumor growth by either maspin-MT2 or EGFP-MT2 cells, did not enhance the weak metastatic activity of maspin-MT2 cells (Supplementary Fig. 5h). As expected5, silencing of IKKα in MT2 cells slowed down tumorigenic growth (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b) and completely inhibited pulmonary metastasis, even in mice given exogenous RANKL (Supplementary Fig. 6c), while up-regulating maspin expression (Supplementary Fig. 6d).

RANKL treatment of freshly isolated primary tumor cells or cells with reduced Rank gene dosage did not affect primary mammosphere formation (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). Although RANKL was reported to enhance metastatic activity of diverse cancer cell lines by enhancing their motility16, no significant effect of RANKL on motility or invasiveness of MT2 cells was observed (Supplementary Fig. 7c). In vivo, RANKL treatment decreased the number of apoptotic cells in late-stage tumors (Supplementary Fig. 7d). Conversely, IKKα silencing increased the frequency of apoptotic cells in late-stage tumors by 2.2-fold and this was not reversed by RANKL treatment (Supplementary Fig. 7e, f). RANKL treatment of mice injected with RANKL pre-treated MT2 cells via the tail vein enhanced their extravasation into the lung and this effect was RANK dependent (Supplementary Fig. 7g). Correspondingly, in vitro RANKL strongly inhibited the apoptotic death of suspended MT2 cells (Supplementary Fig. 7h). These results suggest that the pro-metastatic effects of RANKL and IKKα may be due to increased survival of circulating metastasis-initiating cells.

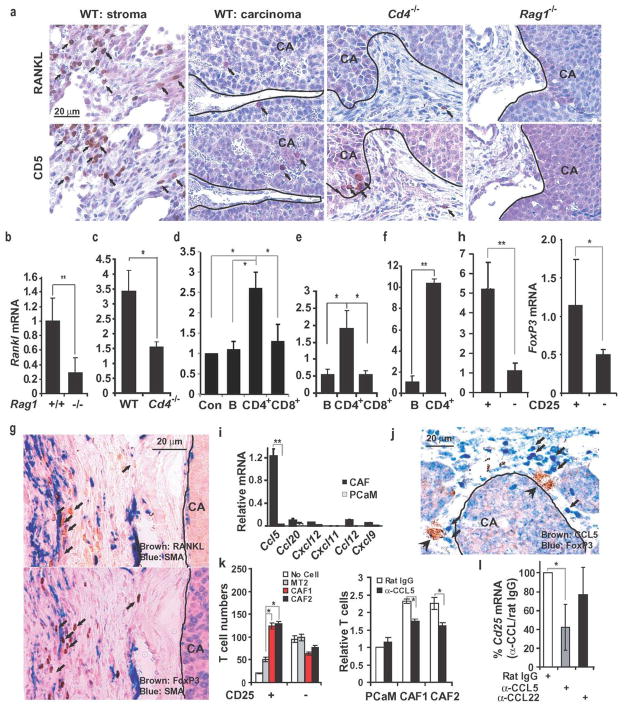

RANKL expression was detected in tumor stroma but not in the carcinoma portion of ErbB2-induced mammary tumors (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 8b) or within metastatic lung nodules, which were surrounded by a few CD5+ lymphocytes (Supplementary Fig. 8a). As activated lymphocytes are a primary source of RANKL during inflammation17 and are present in stroma of breast tumors18, we examined their role in tumor RANKL expression. Staining of parallel tumor sections revealed an almost identical distribution of RANKL+ and CD5+ cells (Fig. 2a), which could be either B1 or T lymphocytes. Correspondingly, tumors grown in Rag1−/− mice, which lack mature T and B cells (Supplementary Fig. 9), contained lower amounts of Rankl mRNA than tumors grown in WT mice (Fig. 2b) and were completely devoid of RANKL+ cells (Fig. 2a). A similar decrease in Rankl mRNA was seen in tumors grown in Cd4−/− mice (Fig. 2c), which lack only CD4+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 9). Tumors raised in Cd4−/− mice were almost completely devoid of RANKL+ cells, although they contained a few adjacent CD5+ cells (Fig. 2a). To further identify the major RANKL-expressing cell type in metastatic mammary tumors, we grew MT2 cells in mammary glands of Rag1−/− mice that were reconstituted with splenic B cells, CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells from WT FVB/N mice. Reconstitution efficiency was confirmed by flow cytometry at the experiment’s end (Supplementary Fig. 10). Only CD4+ T cell reconstitution resulted in a substantial increase in tumor Rankl mRNA above the low basal level in mock-reconstituted Rag1−/− mice (Fig. 2d). We also isolated B cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from spontaneous MMTV-ErbB2 tumors and analyzed them for Rankl mRNA, which was highest in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2e). Likewise, CD4+ T cells from MT2 mammary tumors grown in WT FVB/N mice contained much more Rankl mRNA than B cells from the same tumors (Fig. 2f). Despite their lower contribution to Rankl mRNA expression, CD8+ T cells were more numerous within mammary tumors than CD4+ T cells and both T cell subsets were far more numerous than tumor-infiltrating B cells (Supplementary Fig. 11a). The absence of lymphocytes in Rag1−/− mice did not affect the amount of tumor-associated macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 11b) and no differences in composition of tumor stroma were found between tumors grown in FVB/N or MMTV-ErbB2/Fvb mice (Supplementary Fig. 2d, e). Amongst different types of CD4+ T cells, FoxP3+ Treg cells exhibited the most similar distribution to RANKL+ cells in parallel mammary tumor sections (Fig. 2g). Notably, Treg cells in breast cancer are associated with an invasive phenotype and poor prognosis9,10. The majority of FoxP3+ and RANKL+ cells were in contact with SMA+ cells within the tumor stroma (Fig. 2g). Congruently, CD4+CD25+ tumor T cells, which are FoxP3+ enriched19, expressed 4-fold more Rankl mRNA than CD4+CD25− T cells (Fig. 2h). Co-staining of tumor sections revealed that FoxP3 and RANKL were co-localized (Supplementary Fig. 12a). These results suggest that tumor-infiltrating CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells are the most critical cells for maintaining high RANKL expression within the microenvironment of metastatic mammary tumors.

Figure 2. Expression of RANKL in mammary tumors depends on CD4+ T cells.

a, Mammary glands of indicated mouse strains were inoculated with 1×106 MMTV-ErbB2 PCaM cells. After 56 days, tumors were isolated, fixed, paraffin embedded and sectioned. Parallel sections were stained with RANKL- and CD5-specific antibodies and counterstained with hematoxylin. Panels show the stroma- and carcinoma-containing regions separated by a line, when relevant. Arrows indicate CD5+ and RANKL+ cells. b–f, Rankl mRNA expression in tumors. b, MT2 cells were transplanted into the #2 mammary glands of indicated mice. After 56 days, tumors were excised and Rankl mRNA was quantitated by q-RT-PCR and normalized to cyclophilin mRNA. Results are means +/− s.e.m. (n=3). c, Freshly-isolated MMTV-ErbB2 PCaM cells were transplanted as above into indicated mice. After 56 days, tumors were isolated and Rankl mRNA was quantified. Results are means +/−s.e.m. (n=3). d, MT2 cells were transplanted into mock-, B cell-, CD4+ T cell- or CD8+ T cell-reconstituted Rag1−/− mice, 3 days after reconstitution. Rankl mRNA in tumors was analyzed as above. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=3). e, Spontaneous MMTV-ErbB2 tumors were dissociated into single cell suspensions. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were enriched by positive selection and Rankl mRNA was quantified as above. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=3). f, Tumor-infiltrating B cells and CD4+ T cells were purified from MT2 formed tumors and analyzed for Rankl mRNA. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=3). *: P<0.05; **: P<0.01. g, Parallel sections of tumors raised in WT mice as in a. were stained with FoxP3 (brown)-, RANKL (brown)- and SMA (blue)-specific antibodies without counterstaining. Arrows: FoxP3+ and RANKL+ cells. The stroma and carcinoma regions are separated by a line. h, Tumor-infiltrating CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells were purified and analyzed for Rankl and FoxP3 mRNA expression as above. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=3). *: P<0.05; **: P<0.01. i, Cancer associated fibroblasts (CAF) and PCaM cells were purified from MMTV-ErbB2 tumors. Chemokine mRNAs were quantified by qRT-PCR as above. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=3). **: P<0.01. j, Sectioned MMTV-ErbB2 tumors were stained with CCL5- (brown) and FoxP3-(blue) specific antibodies. k, The indicated cell types were plated onto multiwell plates at 2X105 cells per well with 3 μg/ml rat IgG or CCL5 antibody. Splenocytes from tumor-bearing MMTV-ErbB2 mice were added to the upper compartment of Boyden chambers. After 24 hrs, T cells in the bottom compartment were quantified by flow cytometry. CAF1 and CAF2, two independent preparations. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=3). *, P<0.05. l, Rat IgG, CCL5, or CCL22 antibodies (2 mg/kg) were i.p. injected into FVB/N females bearing MT2 tumors twice weekly. After one week, tumors were excised and Cd25 mRNA was quantified by q-RT-PCR and normalized to cyclophilin mRNA. Results are means +/− s.e.m. (n=4). *, P<0.05. CA, carcinoma region.

The proximity of RANKL+ T cells to SMA+ cells, which expressed fibroblast markers (Supplementary Fig. 13), prompted us to examine whether the latter express T cell-attracting chemokines. CCL5/RANTES, a T cell chemokine involved in breast cancer metastasis20,21 was expressed by, but not PCaM from mammary tumors (Fig. 2i). Expression of CCR1, one of the cognate CCL5 receptors22, was strongly elevated in tumor CD4+ T cells relative to splenic CD4+ T cells of tumor-bearing or naïve mice (Supplementary Fig. 12b, left panel). Notably, CD4+CD25+ tumor T cells expressed more Ccr1 mRNA than CD4+CD25− tumor T cells (Supplementary Fig. 12b, right panel). Furthermore, tumor-infiltrating FoxP3+ T cells were in close proximity to CCL5+ stromal cells (Fig. 2j) and preferentially attracted CD4+CD25+ T cells relative to CD4+CD25− T cells from spleens of tumor-bearing mice, although the latter were 6-times more abundant in unselected splenocytes (Fig. 2k, left panel). This recruitment was partially dependent on CCL5/RANTES (Fig. 2k, right panel). CCL5 neutralization also inhibited recruitment of tumor-associated CD25+ cells in vivo (Fig. 2l).

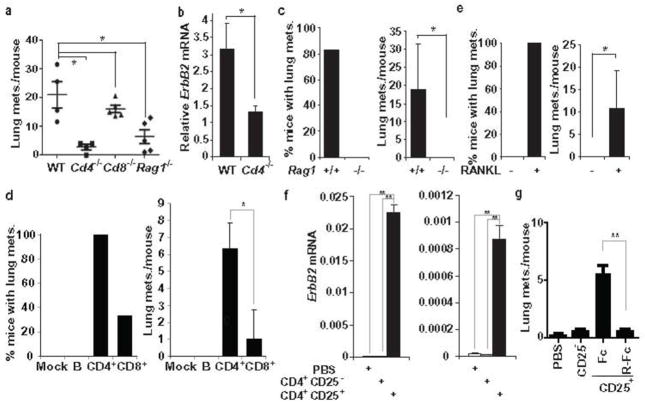

To examine whether CD4+ T cells were required for stimulation of pulmonary metastasis, we transplanted freshly isolated PCaM cells from MMTV-ErbB2-induced tumors into mammary glands of WT, Rag1−/−, Cd4−/− and Cd8−/− mice, all in the FVB/N background. Although primary tumor volume was a bit larger in Cd4−/− and Rag1−/− mice than in WT or Cd8−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. 14a), pulmonary metastasis was greatly diminished in Cd4−/−and Rag1−/− mice, but unaltered in Cd8−/−mice (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 14b). PCR-mediated ErbB2 mRNA quantitation confirmed a 3-fold decrease in pulmonary metastasis in Cd4−/− mice (Fig. 3b). A dramatic decrease in pulmonary metastasis was exhibited by Rag1−/− mice inoculated with MT2 cells (Fig. 3c) but this was restored by transplantation of CD4+ T cells and to a much lesser extent by CD8+ T cells, whereas B cell transplantation had no effect (Fig. 3d). Administration of exogenous RANKL to MT2-inoculated Rag1−/− mice restored pulmonary metastasis in the complete absence of T cells (Fig. 3e). CD4+CD25+ were far more effective in restoring pulmonary metastasis in MT2-inoculated Rag1−/− mice (Fig. 3f) and this effect was almost completely blocked by administration of RANK-Fc (Fig. 3g).

Figure 3. Tumor infiltrating CD4+ T cells stimulate pulmonary metastasis.

a–b, Freshly-isolated MMTV-ErbB2 PCaM cells (1×106) were transplanted into the #2 mammary glands of indicated mice. a, Lung metastasis incidence and multiplicity were determined 56 days later. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=4–6). Each point represents a value from a single mouse. b, Pulmonary metastasis in indicated mice inoculated with PCaM cells was quantified by qRT-PCR analyses of lung RNA with MMTV-ErbB2 specific primers. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=4). c, MT2 cells were transplanted as above. After 56 days, pulmonary metastasis incidence and multiplicity were quantified. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=6). d, MT2 cells were transplanted into Rag1−/− mice reconstituted with indicated cell types, 3 days after reconstitution. After 35 days, lung metastasis incidence and multiplicity were quantified. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=3). e, MT2-inoculated Rag1−/− mice were treated with BSA or RANKL (80 μg/kg) twice weekly, starting one week post-inoculation. After 35 days, lung metastasis incidence and multiplicity were determined. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=6–7). f, MT2 cells were transplanted into Rag1−/− mice reconstituted with indicated cell types as in d. Lung metastases were measured by Q-RT-PCR of ErbB2 mRNA on day 56 post-inoculation. Each plot represents ErbB2 mRNA expression from an independent littermate group. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=3). g, MT2 cells were transplanted into Rag1−/− littermate females reconstituted with PBS, CD4+CD25− or CD4+CD25+ cell, as above. After one week, the CD4+CD25+ reconstituted mice were treated with control Fc or RANK-Fc (2.5 mg/kg) twice weekly. Pulmonary metastasis multiplicity was calculated on day 35 post-inoculation. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=4–5). *: P<0.05; **: P<0.01.

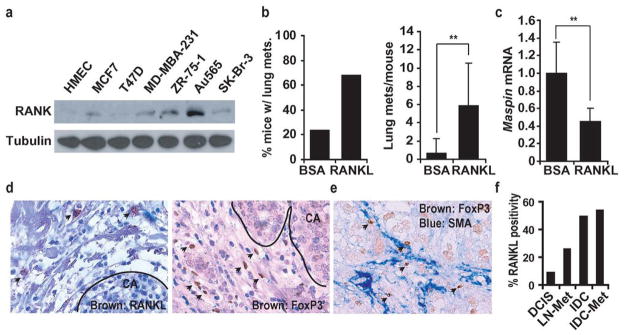

We examined whether RANK signaling stimulates metastasis of human breast carcinoma cells. Of 19 cell lines, Au565, SKBR-3, ZR-75-1 and SUM-1315 were the highest RANK expressors (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. 15a). None of the examined cell lines expressed more RANKL than normal human mammary epithelial cells with progesterone (Supplementary Fig. 15b). ZR-75-1 and Au565 cells were inoculated into the #2 mammary glands of nude mice. Whereas Au565 cells failed to form tumors, ZR-75-1 cells formed slow growing primary tumors (data not shown) that gave rise to pulmonary metastases in 20% of mice with an average multiplicity of less than 1 nodule per lung (Fig. 4b). Human RANKL administration increased metastasis incidence and multiplicity by 3-fold and 10-fold, respectively (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, RANKL administration decreased maspin expression in ZR-75-1 tumors by 2.5-fold (Fig. 4c). RANK-negative T47D cells did not respond to RANKL administration (Supplementary Fig. 16). RANKL+ and FoxP3+ cells were also present in the tumor-associated stroma of human breast cancer (Fig. 4d), in close proximity to SMA+ cells (Fig. 4e). RANKL expression was higher in invasive ductal carcinomas (IDC) than in ductal carcinomas in situ (DCIS) or lymph node-positive tumors (Fig. 4f).

Figure 4. RANKL in human breast cancer.

a, RANK expression in human breast cancer cell lines was analyzed by immunoblotting. b, ZR-75-1 cells were transplanted into the #2 mammary glands of Nude mice. Mice were treated with BSA or RANKL (80 μg/kg) twice weekly, starting one week post-inoculation. After 84 days, lung metastasis incidence and multiplicity were determined. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=6). c, Maspin mRNA in ZR-75-1-transplanted tumors treated with BSA or RANKL was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Means +/− s.e.m. (n=6). **: P<0.01. d, Human breast cancer sections were stained with FoxP3- and RANKL-specific antibodies and counterstained with hematoxylin. Arrows: FoxP3+ and RANKL+ cells. CA, carcinoma region. e, Human breast cancer sections were stained with FoxP3- (brown) and SMA- (blue) specific antibodies without counterstaining. f, Tissue arrays containing 50 samples each of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), invasive ductal carcinoma without metastasis(IDC), IDC with metastasis (IDC-Met), and lymph node macro-metastasis (LN-Met) were analyzed for RANKL-expressing cells. Samples were considered positive when at least two cells/field (200x) were RANKL+.

Our results provide a new mechanistic explanation for the association of CD4+ and Treg markers with a more aggressive behavior in advanced breast cancers9,10,18,23, by demonstrating that tumor-infiltrating CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells are a major source of RANKL production. RANKL expressed by these cells stimulates metastatic progression through RANK, expressed by metastasizing breast/mammary carcinoma cells (Supplementary Fig. 17). These findings and the demonstration that the pro-metastatic function of T cells can be replaced by exogenous RANKL are different from those obtained in the MMTV-PyMT model in which CD4+ Th2 cells stimulate tumor progression through IL-4 which caused the M2 polarization of tumor-associated macrophages18. Our findings in MMTV-ErbB2 mice correlate well with human breast cancer. In both cases, RANKL+ and FoxP3+ Treg cells were concentrated in the tumor stroma and were not in contact with carcinoma cells. Furthermore, in both cases, tumoral FoxP3+ cells correlated with invasion, metastasis and poor prognosis9,10,23,24. Recruitment of CD4+CD25+ T cells to CAFs is partially dependent on CCL5/RANTES, a chemokine associated with human breast cancer grade and metastasis20,21. Our findings, which suggest that CAFs and CCL5/RANTES act through T cells in addition to direct effects on carcinoma cells20, are consistent with the observation that CAF depletion in mammary tumors decreased Treg infiltration and pulmonary metastasis25. We suggest that the potent pro-metastatic effect of tumor-infiltrating Treg cells can be dismantled through the use of RANKL-RANK antagonists, which should leave the potential anti-tumorigenic activity of Th1 cells intact. Therefore, RANK signaling inhibitors may be used in conjunction with surgical resection of primary breast tumors and anti-tumor immunotherapy to prevent recurrence of metastatic disease. It should also be noted that RANKL can mediate the breast cancer promoting activity of progestins, which induce its expression by pre-malignant cells26,27.

METHODS SUMMARY

A detailed Methods section is available in Supplementary Information. C57BL6 Rank+/−mice11 were backcrossed to FVB/N MMTV-ErbB2 mice for at least 6 generations. FVB/N MMTV-ErbB2/Rank+/− mice were intercrossed to generate FVB/N MMTV-ErbB2/Rank+/+ and FVB/N MMTV-ErbB2/Rank+/− mice. Cd4−/−, Cd8−/− and Rag1−/− mice were maintained in the FVB/N background. Single PCaM or MT2 cell suspensions were prepared and injected into the #2 mammary gland. Tumor size was measured weekly with a caliper. At the end of the study, mice were sacrificed and primary tumors and lungs were analyzed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Coussens for discussions and suggestions, V. Temkin and G. He for scientific and technical advice and H. Herschman for critical reading. Work was supported by the National Institutes of Health. W.T. and W.Z. were supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. A.S and S.G were supported by NIH Asthma Research and Cancer Therapeutic training grants and a Research Fellowship Award from Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, respectively. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.K. (karinoffice@ucsd.edu) who is an American Cancer Society Research Professor.

References

- 1.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 140(6):883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo JL, et al. Nuclear cytokine-activated IKKalpha controls prostate cancer metastasis by repressing Maspin. Nature. 2007;446 (7136):690–694. doi: 10.1038/nature05656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fata JE, et al. The osteoclast differentiation factor osteoprotegerin-ligand is essential for mammary gland development. Cell. 2000;103 (1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao Y, et al. IKKalpha provides an essential link between RANK signaling and cyclin D1 expression during mammary gland development. Cell. 2001;107 (6):763–775. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao Y, Luo JL, Karin M. IkappaB kinase alpha kinase activity is required for self-renewal of ErbB2/Her2-transformed mammary tumor-initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104 (40):15852–15857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706728104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guy CT, et al. Expression of the neu protooncogene in the mammary epithelium of transgenic mice induces metastatic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89 (22):10578–10582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slamon DJ, et al. Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989;244 (4905):707–712. doi: 10.1126/science.2470152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiwari RK, Borgen PI, Wong GY, Cordon-Cardo C, Osborne MP. HER-2/neu amplification and overexpression in primary human breast cancer is associated with early metastasis. Anticancer Res. 1992;12 (2):419–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohling SD, Allison KH. Immunosuppressive regulatory T cells are associated with aggressive breast cancer phenotypes: a potential therapeutic target. Mod Pathol. 2008;21 (12):1527–1532. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohara M, et al. Possible involvement of regulatory T cells in tumor onset and progression in primary breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58 (3):441–447. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0570-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dougall WC, et al. RANK is essential for osteoclast and lymph node development. Genes Dev. 1999;13 (18):2412–2424. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.18.2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Body JJ, et al. Effects of Denosumab in Patients with Bone Metastases, with and without Previous Bisphosphonate Exposure. J Bone Miner Res. 2009 doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fizazi K, et al. Randomized phase II trial of denosumab in patients with bone metastases from prostate cancer, breast cancer, or other neoplasms after intravenous bisphosphonates. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 (10):1564–1571. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ercolini AM, et al. Recruitment of latent pools of high-avidity CD8(+) T cells to the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 2005;201 (10):1591–1602. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu H, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor family member RANK mediates osteoclast differentiation and activation induced by osteoprotegerin ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96 (7):3540–3545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones DH, et al. Regulation of cancer cell migration and bone metastasis by RANKL. Nature. 2006;440 (7084):692–696. doi: 10.1038/nature04524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawai T, et al. B and T lymphocytes are the primary sources of RANKL in the bone resorptive lesion of periodontal disease. Am J Pathol. 2006;169 (3):987–998. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeNardo DG, et al. CD4(+) T cells regulate pulmonary metastasis of mammary carcinomas by enhancing protumor properties of macrophages. Cancer Cell. 2009;16 (2):91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4 (4):330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karnoub AE, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007;449 (7162):557–563. doi: 10.1038/nature06188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luboshits G, et al. Elevated expression of the CC chemokine regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) in advanced breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59 (18):4681–4687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao JL, et al. Structure and functional expression of the human macrophage inflammatory protein 1 alpha/RANTES receptor. J Exp Med. 1993;177 (5):1421–1427. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gobert M, et al. Regulatory T cells recruited through CCL22/CCR4 are selectively activated in lymphoid infiltrates surrounding primary breast tumors and lead to an adverse clinical outcome. Cancer Res. 2009;69 (5):2000–2009. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bates GJ, et al. Quantification of regulatory T cells enables the identification of high-risk breast cancer patients and those at risk of late relapse. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24 (34):5373–5380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.9584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao D, Luo Y, Markowitz D, Xiang R, Reisfeld RA. Cancer associated fibroblasts promote tumor growth and metastasis by modulating the tumor immune microenvironment in a 4T1 murine breast cancer model. PLoS One. 2009;4 (11):e7965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez-Suarez E, et al. RANK ligand mediates progestin-induced mammary epithelial proliferation and carcinogenesis. Nature. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nature09495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schramek D, et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor RANKL controls development of progestin-driven mammary cancer. Nature. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nature09387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.