Abstract

Mercuric compounds are persistent global pollutants that accumulate in marine organisms and in humans who consume them. While the chemical cycles and speciation of mercury in the oceans are relatively well described, the cellular mechanisms that govern which forms of mercury accumulate in cells and why they persist are less understood. In this study we examined the role of multidrug efflux transport in the differential accumulation of inorganic (HgCl2) and organic (CH3HgCl) mercury in sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) embryos. We found that inhibition of MRP/ABCC-type transporters increases intracellular accumulation of inorganic mercury but had no effect on accumulation of organic mercury. Similarly, pharmacological inhibition of metal conjugating enzymes by ligands GST/GSH significantly increases this antimitotic potency of inorganic mercury, but had no effect on the potency of organic mercury. Our results point to MRP-mediated elimination of inorganic mercury conjugates as a cellular basis for differences in the accumulation and potency of the two major forms of mercury found in marine environments.

Introduction

The physical properties of chemicals are widely used to predict their potential to enter cells and accumulate in organisms. For example hydrophobicity, measured as an octanol–water partition coefficient (Kow), is often proportional to chemical bioconcentration in tissues relative to the environment (1, 2). A key limitation of these predictions is that they do not account for cellular mechanisms that limit or enhance accumulation. The significance of this problem is underscored by the fact that the accumulation of some persistent global pollutants is not predicted from their hydrophobicity.

Mercuric compounds are a striking example; they are not exceedingly hydrophobic (log Kow < 0.6), yet some of them bioconcentrate in higher trophic level marine organisms at levels similar to those seen for highly hydrophobic compounds such as PCBs (3–6). Furthermore, although organic mercury is the predominant form that accumulates in marine organisms, inorganic mercury is slightly more hydrophobic (HgCl2 log Kow = 0.52) than organic mercury (CH3HgCl log Kow = 0.23). These observations suggest that differences in how these compounds gain entry to cells, react with intracellular ligands, or are subsequently eliminated play a significant role in their observed biological persistence. The primary question posed here is whether different cellular handling of the two forms of marine mercury leads to differences in their accumulation.

In this study we specifically examined the roles of two types of ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) efflux transporters (7–9), the ABCB/p-glycoprotein (P-gp) and the ABCC/multidrug resistance associated protein (MRP) transporters in determining mercury accumulation. These evolutionarily conserved transporters, also known as multidrug transporters, use ATP to pump a wide variety of environmental compounds out of cells, reducing accumulation to levels less than those predicted by their hydrophobicity (10). The ABCB family prevents accumulation of organic compounds and directly effluxes the unmodified chemical from the cell (11–13). The ABCC family can similarly efflux the unmodified chemical from the cell and can also act on compounds following intracellular modification such as conjugation to glutathione (GSH) (9, 14, 15). These transporters have been previously shown to protect a phylogenetically diverse array of organisms, including yeast (16), plants (17), nematodes (18), and fish (19), against environmental metals such as cadmium and arsenic. Relevant to this study, recent studies in mammals indicate that the ABCC/MRP transporters in particular can eliminate mercuric compounds as thiol conjugates (20, 21).

To assess the roles of these multidrug transporters in protection from mercury we used sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) embryos, a tractable marine cell-biological system that has a fully sequenced genome and relatively well-characterized chemical defense genes and activities. The embryos have an expanded repertoire of ABC transporter genes and ABCB and ABCC transport activity (12, 22, 23). S. pupuratus also have 38 glutathione-S-transferase (GST) genes (23), which encode enzymes that catalyze the conjugation of toxicants to glutathione (GSH; (24)). Of the 38 GST genes in the genome, 14 are orthologous to these detoxification-related GSTs and the mRNAs of this subset of genes are expressed in embryos and larvae (24). Finally, the embryos contain large amounts of at least two antioxidants (potential carriers for mercury) glutathione and ovothiol, each at 5 mM concentration in the egg (24, 25).

Using the antimitotic action of mercuric compounds as an indirect assay of intracellular mercury accumulation, we tested the potency of mercury in the presence or absence of conjugation and transporter inhibitors and then validated the results obtained with this assay by direct measurement of intracellular mercury accumulation. Our results indicate that the sea urchin MRP-like transport activity is significantly more effective at limiting accumulation and potency of inorganic mercury than organic mercury. These differences in handling could be an important factor underlying the enhanced accumulation of organic, as compared to inorganic, mercury.

Experimental Section

Reagents

Paraformaldehyde was purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA) and MK571 was from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI). PSC833 was a gift from Norvartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. (Basel, Switzerland). Cyclosporin-A (CS-A) was obtained from BIOMOL Research Laboratories Inc. (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Calcein-acetoxymethylester (C-AM), 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and Alexa Fluor Phalloidin 488 were purchased from Invitrogen Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Mouse monoclonal Anti-β-Tubulin-Cy3 antibody (clone 2.1), inorganic mercury (HgCl2), 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB), ethacrynic acid (EA), potassium chloride (KCl), dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO), and Verapamil were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Organic mercury (CH3HgCl) stock solutions (100 µM) were purchased from Brooks Rand Trace Metals Analysis and Products (Seattle, WA). DMSO was used as a solvent for all stock solutions except inorganic mercury (HgCl2) stock, which was prepared in 1.0 µm filtered seawater (FSW), and organic mercury stock, which was provided in 0.5% acetic acid (HAc) and 0.2% hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution.

Animals

Adult purple sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) were kept at the Hopkins Marine Station (Pacific Grove, CA) in flow-through 13 ± 2 °C seawater tanks and were fed kelp (Macrocytis pyrifera) weekly. Gametes were collected and fertilized as described previously (26). Prior to use in experiments, eggs were washed several times in 1.0 µm FSW. Sperm was stored dry at 4 °C until use. Fertilization success was checked under the microscope and only batches of embryos exhibiting >90% successful fertilization were used for subsequent experiments. All experiments were conducted at 14–15 °C.

Effects of Organic and Inorganic Mercury on Mitosis

Eggs were washed several times using FSW, brought to a concentration of 1000 eggs/mL, and fertilized with diluted sperm. Twenty minutes after fertilization, 3 mL of this embryo culture was transferred into each well of Falcon polystyrene (12-well) multiwell plates (Benton Dickson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Solvent controls, mercury, and/or inhibitors were then added to each well. Since multidrug efflux activity is up-regulated ~25 min post fertilization (PF) in S. purpuratus (12), embryo exposures to HgCl2, CH3HgCl, and/or other reagents were started after activation of efflux at 30 min PF. The final concentrations of HgCl2 were 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, and 2 µM, and of CH3HgCl were 0.01, 0.025, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1, 0.125, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.5 µM. Plates of embryos were incubated at 14 °C with gentle shaking. When >90% of control embryos reached the two-cell stage, (~130 min PF), embryos were fixed using 30–50 µL of 3.2% paraformaldehyde/well. Development to the 2-cell stage was then assessed from 100 embryos/well. The maximum concentration of solvent (DMSO) within any experiments did not exceed 0.5% of final volumes; maximum concentrations of HAc and HCl in organic mercury solutions used did not exceed 0.001%. In all experiments the controls were treated with solvent equivalent to the highest concentration for the respective inhibitor/compound(s).

Susceptibility of Embryos to Mercury in the Presence of Transporter or GSTs Inhibitors

Several batches of embryos were prepared as described above. Embryos were exposed to 0.5 µM HgCl2 or 0.1 µM CH3HgCl in the presence/absence of transporter (MK571, PSC833, Verapamil or CS-A) or GSTs (CDNB and EA) inhibitors. Embryos were then fixed and scored as described above.

Mercury Accumulation in the Presence of the MRP Inhibitor MK571 or Pgp Inhibitor PSC833

Fourteen mL of 30 min old embryos (1000 embryos/mL) were incubated for 90–100 min in preweighed 15 mL polystyrene tubes (BD Falcon, BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) containing either solvent (DMSO) control, 20 µM MK571 inhibitor control, 10 µM PSC833 inhibitor control, mercuric compounds alone (0.5 µM HgCl2 and 0.1 µM CH3HgCl), or mercuric compounds with transporter inhibitors. Tubes were sealed and gently mixed using a Vari-mix (Barnstead/Thermolyne, Dubuque, IA) at 15 °C. After incubation, embryos were pelleted by centrifugation for 5 min at 750 rpm; supernatant seawater was aspirated and the embryo pellet was resuspended in 15 mL of 1 µm-filtered seawater, followed by repeated centrifugation. Three of these “washes” were performed and tubes containing washed, pelleted embryos were reweighed and pellet wet weight was determined prior to freezing of pelleted samples (−20 °C) for mercury analysis.

Total Hg Analysis

Mercury was measured using a Direct Mercury Analyzer 80 (Milestone Inc., Shelton, CT) following EPA method 7473 (27). Briefly, controlled heating in an oxygenated decomposition furnace is used to liberate mercury from samples in the instrument. Decomposition products are carried by oxygen to a catalytic column where oxidation and removal of interfering compounds occurs. Finally, mercury is trapped on an amalgamator followed by rapid heating, releasing mercury vapor, and measurement by atomic absorbance at 253.7 nm. Accuracy, as determined by recoveries of spiked samples and the certified reference materials (NIST 2976, 0.061 µg Hg g−1 dw tissue; NRC Dorm-3, 0.382 µg Hg g−1 dw tissue), averaged 106 ± 21% (n = 4), 117 ± 5% (n = 3), and 100 ± 7% (n = 4) respectively. The method detection limit (MDL), defined as three times the standard deviation of nine determinations of spiked tissue, was 0.012 µg Hg g−1 wet weight tissue. Masses of embryo pellets analyzed were used to calculate intracellular mercury concentrations; the radius and volume of a 1-cell sea urchin embryo are approximately 80 µm and 270 pL, respectively.

Characterization of the Effects of Mercury on the Mitotic Apparatus

Eggs, pooled from 3 females, were fertilized and the embryos were then separated into different beakers and treated with either HgCl2 or CH3HgCl in the presence/absence of 5 µM MK571 or control groups (no mercury, no MK571) and a group treated with 5 µM MK571 alone (5 µM). The effects across the range of concentrations for HgCl2 (0.05–2 µM) and CH3HgCl (0.01–0.3 µM) were examined. When >90% of controls reached the two-cell stage, all embryos were fixed in buffer (100 mM Hepes, 50 mM EGTA, 10 mM MgSO4, 0.75 Md-glucose, 0.2% Triton-X100, titrated to pH 7.3 with KOH), containing 2% paraformaldehyde (28). Following fixation, embryos were washed several times then blocked using Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) and 2% bovine serum albumin. Microtubules were labeled with anti-β-tubulin-Cy3 antibody (Sigma), DNA labeled with DAPI, and microfilaments labeled using 100 nM Alexa Fluor Phalloidin 488 (28). Image of microtubules, microfilaments, and DNA were acquired using a 40× objective on a Zeiss Axiovert S-100 inverted microscope.

Data Analysis and Presentation

The percentage of 2-cell embryos was used as a measure of mercury toxicity. Data from each set of individual mercury experiments were first analyzed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality and then with Bartlett test for homogeneity of variances; all data presented were normally distributed and had homogeneous variance. All data, except the mitotic apparatus fixation experiment, represent the data of 3–12 replicates (i.e., 3–12 individual batches of embryos); mean, standard deviation, and EC50 values of these replicates experiment were calculated and plotted using Sigma Plot software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). The trendlines of mean values were plotted using four-parameter logistic curve nonlinear regression. Changes in EC50 concentrations of mercury, in the presence or absence of inhibitors, were compared by paired t test; p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data are represented as mean ± 1 standard deviation.

Results and Discussion

Mercuric Compounds Interfere with Mitosis in Sea Urchin Embryos

To rapidly assess the sensitization of embryos to mercury by inhibition of efflux transport, we developed a simple assay of mercury toxicity. Previous studies indicated that a major mode of action for mercury toxicity on dividing cells is through its binding and depolymerization of tubulin filaments (29, 30) and possibly through effects on centrosomal proteins (31). Based on these observations we measured the success of the first cell division in the presence of mercuric compounds and detailed the specific effects of mercuric compounds on the mitotic apparatus of the embryos. Both HgCl2 and CH3HgCl impaired mitosis as measured by the progression through telophase and into the 2-cell stage at ~130 min post fertilization. CH3HgCl was 5 times more potent than HgCl2 at interfering with mitosis and the overall average EC50 values for CH3HgCl and HgCl2 were 124 and 610 nM, respectively (Figure S1A–D).While both compounds interfere with the mitotic apparatus causing shortened astral microtubules (Figure 1C and Figure S1) leading to embryos arrested in prophase and metaphase, the HgCl2-treated embryos generally had disordered spindles and shortened astral microtubules relative to controls while CH3HgCl had a more pronounced impact on spindle formation prior to metaphase occasionally leading to anastral (lacking obvious polarity) spindles (Figure S1B–D).

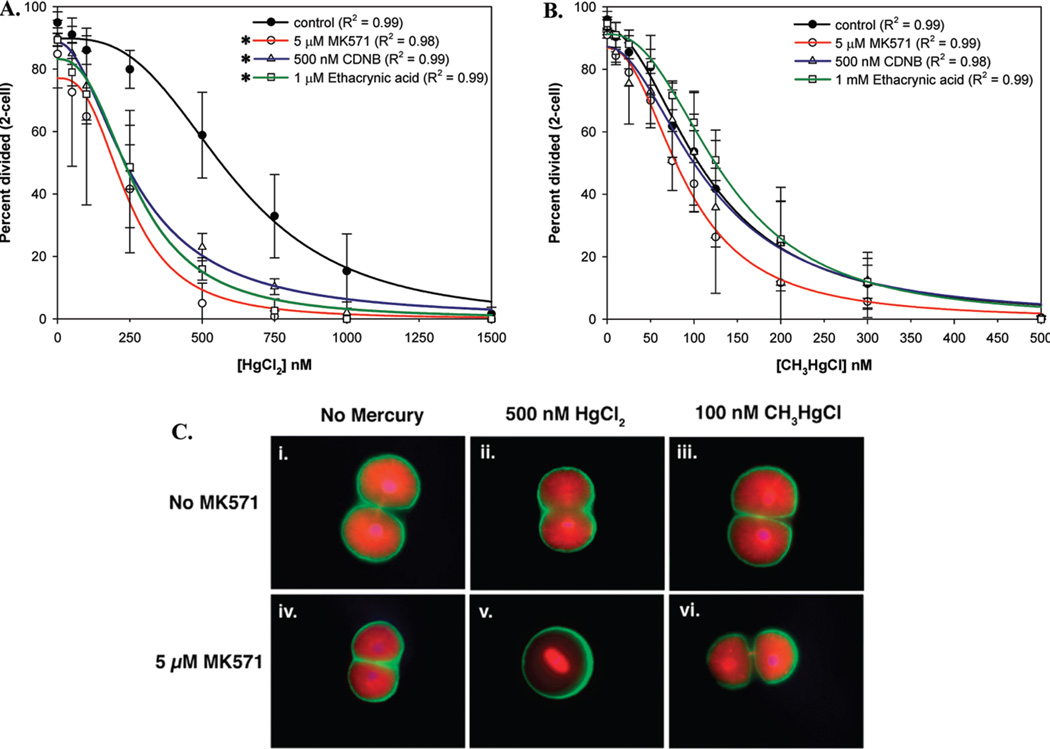

FIGURE 1.

Competitive inhibition of MRP activity using 5 µM MK571, or GST/GSH using CDNB or EA, sensitized the embryos to HgCl2 (A) but not to CH3HgCl (B). The data are expressed as percentage of embryos reaching 2-cell stage 125 min postfertilization and represent the average ± SDs of 3–5 independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences in mean EC50 values in inhibitor treated embryos (p < 0.05). (C) Immunofluoresence micrographs of sea urchin embryos treated with 500 nM HgCl2 or 100 nM CH3HgCl in the absence (II and III) or presence (V and VI) of 5 µM MK571 as compared to the control embryos (I and IV). Microfilaments are green, microtubules are red, and DNA is blue.

Studies on marine diatoms indicate that that the major mode of entry for both inorganic and organic mercury is through passive diffusion of the charge neutral forms (5, 6) and that the abundance of these forms is a function of both pH and pCl−. In seawater, the differences in baseline potency of the two forms may then be due to the predominance of the charged, and less membrane-permeant, form of inorganic mercury (95% HgCl4−, 5% HgCl2). In contrast, most organic mercury is present as a neutral charge complex (CH3HgCl) in seawater (4, 5). Despite these differences we, and the previous study in diatoms, found that the minor fraction of inorganic mercury in the neutral state in seawater is sufficient to drive rapid accumulation of intracellular mercury. In addition, as will be described next, the accumulation of inorganic mercury can be dramatically increased by inhibition of efflux transport, indicating that differential mercury speciation in seawater limited baseline potency of inorganic mercury but was not the primary factor limiting accumulation in our experiments.

Inhibition of MRP Increases Potency of Inorganic Mercury but Has No Effect on Potency of Organic Mercury

To probe the roles of multidrug transporters in differential handling of mercury we exposed the embryos to mercury in the presence or absence of transporter inhibitors and assessed any resultant changes in potency. We examined the effects of Cyclosporin-A, MK571, PSC833, and Verapamil on the sensitivity of dividing embryos to inorganic and organic mercury (12, 32–34). We found that none of the four transporter inhibitors caused any significant increase in sensitivity of the embryos to organic mercury (Figure S2). In contrast, there was a dramatic increase in the antimitotic potency of HgCl2 when efflux activity was inhibited by 5–10 µM MK571 (Figures 1 and S2), suggesting MRP-mediated protection from inorganic mercury. Neither verapamil nor PSC833 had any effect on the potency of 500 nM HgCl2. High levels of cyclosporin (10–20 µM) caused a small, albeit statistically insignificant, reduction in mitosis and this could possibly be due to cyclosporin’s higher relative affinity for MRPs than either verapamil or PSC833 (12, 32–34; Figure S2).

To characterize the extent to which sea urchin embryos are protected from mercury by the MK571-sensitive mechanism, the embryos were exposed to a range of inorganic and organic mercury concentrations along with 5 µM MK571 (Figure 1A, B). This level of MK571, which significantly increased the accumulation of the efflux transporter substrate calcein-AM (Figure S3), also increased the potency of inorganic mercury, shifting the EC50 from 693 to 244 nM (p < 0.05). In contrast there was no significant effect of MK571 on the potency of a wide range of organic mercury concentrations (Figure 1B). Furthermore, inhibition of MRP with MK571 increased the incidence of specific mercury-induced spindle defects in HgCl2-treated embryos but not in CH3HgCl-treated embryos (Figures 1C and S1B–D).

One caveat was that high levels (20 µM) of MK571 induced mitotic delay at 130 min PF even in the absence of mercury and so the mercury effects can not be distinguished from MK571 effects at these levels (Figure S2B). This suggests that an alternative explanation of our results could be that inorganic mercury instead sensitizes the embryos to MK571. To examine this hypothesis we first tested whether moderate levels of inorganic mercury can inhibit canonical multidrug efflux transport (35), thereby increasing permeability to MK571. We found that 500 nM HgCl2 does not cause significant inhibition of calcein-am efflux transport (Figure S3), either in the presence or absence of 5 µM MK571, indicating that this level of inorganic mercury does not increase embryo permeability. Next, as will be elaborated in the subsequent section, we tested whether the inorganic mercury-specific MK571 effects are also seen with inhibitors of GST/GSH, consistent with MRP-mediated selective elimination of inorganic mercury conjugates.

Inhibitors of Glutathione Conjugation Increase Potency of Inorganic Mercury but Have No Effect on Potency of Organic Mercury

Based on our results with MK571, and previous studies suggesting MRP-selective transport of heavy metals as a thiol conjugate, we hypothesized that a primary mechanism for MRP-mediated inorganic mercury elimination in sea urchins would be through efflux of the GSH conjugate (36, 37). We exposed embryos to the two forms of mercury compounds in the presence or absence of CDNB and EA, both of which are substrates for GSTs (38) and ligands for GSH (39). These compounds could then enhance the potency of mercuric compounds by competing for GST and/or depleting free GSH.

Neither CDNB nor EA controls showed impaired cell division, but both compounds caused a significant increase in the potency of inorganic mercury (Figure 1A), resulting in a roughly 2-fold reduction in the EC50 value for HgCl2 to 268 and 273 nM (p < 0.05) for CDNB and EA, respectively. In contrast to inorganic mercury, little change in potency of organic mercury was seen upon cotreatment with CDNB or EA (Figure 1B) and the small differences in CH3HgCl potency in the presence of CDNB or EA were not statistically significant (p value >0.05 for all concentrations). Since P-gp transporters are not thought to transport GSH conjugates (40), the CDNB and EA results are also consistent with the transporter inhibitor results indicating an MRP-like transporter, rather than P-gp, mediates protection from inorganic mercury.

Intracellular Accumulation of Inorganic Mercury, but Not Organic Mercury, Is Increased by Inhibition of Efflux Transport

Based on the observations above, we next hypothesized that inhibition of MRP should result in increased intracellular accumulation of inorganic but not organic mercury. In addition, we predicted that inhibition of P-gp, which has no effect on the potency of either compound, should also have no effect on their intracellular accumulation. To test these predictions, we measured the intracellular concentrations of inorganic and organic mercury in the presence or absence of MK571 or PSC833.

Since we also observed a large difference in the relative potency of the two mercury compounds, we compared the accumulation of the two mercury compounds at similar effective, rather than physical, concentrations of 0.1 and 0.5 µM for organic and inorganic mercury. As these levels of extracellular mercury are near the EC40 levels, the embryos have already accumulated some mercury and are highly sensitive to further increases in extracellular mercury concentration. This sensitivity is reflected in relatively large increases in antimitotic effects such as disordered spindles and shortened astral microtubules, with small increases in extracellular mercury (Figures 1 and S1).

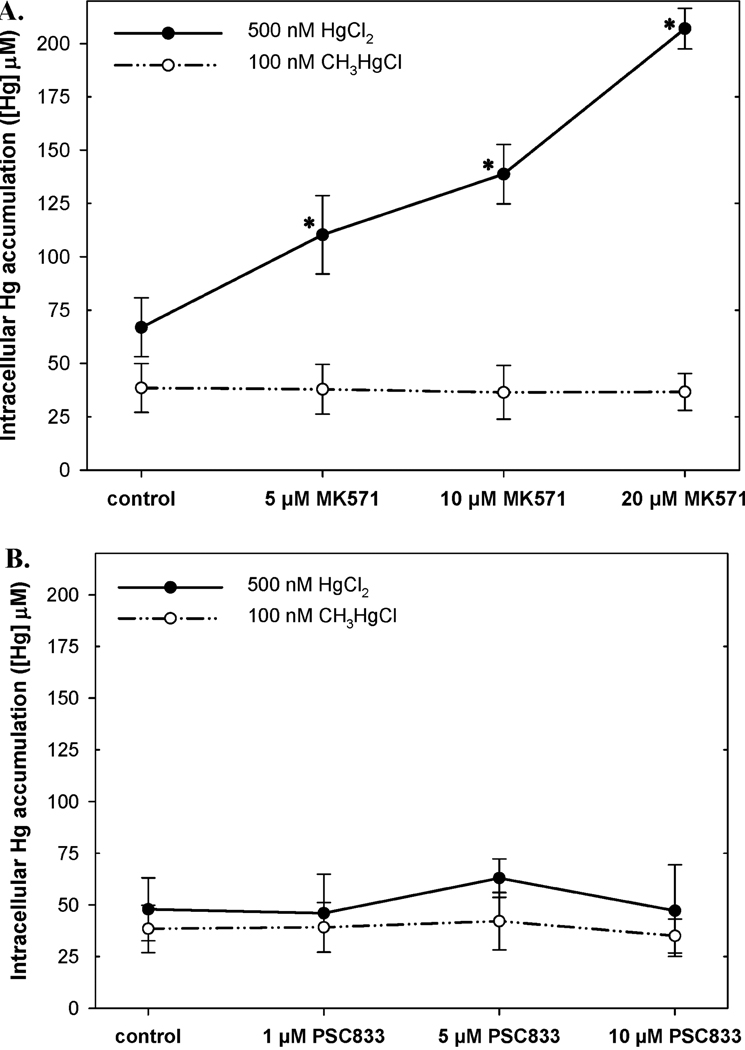

The intracellular concentrations of mercury in the embryos exposed to mercury with no transporter inhibitors present were 56 µM for HgCl2 and 38 µM for CH3HgCl. Relatively low levels (5 µM) of MK571 significantly increased intracellular mercury to 110 µM while 20 µM MK571 caused a nearly 4-fold increase to 207 µM (Figure 2A). Recapitulating what we found with the inorganic-selective effect of transporter and GST/GSH inhibitors on the antimitotic potency of mercury, there was no significant difference in accumulation of mercury in the embryos exposed to organic mercury in the absence or presence of MK571 (Figure 2A). As predicted by the mitotic assay, PSC833 had no effect on accumulation of either mercuric compound (Figure 2B) indicating that an MRP, rather than P-gp, is the major inorganic mercury efflux activity.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of intracellular mercury accumulation (µM) presented in the presence of either MRP (MK571) (A) or P-gp (PSC833) specific inhibitor (B). Each graph compares intracellular mercury accumulation (µM) of both forms of mercury (HgCl2 - solid line; CH3HgCl - dotted line). Mercury accumulation data are represented as the average ± SDs of four separate measurements. Asterisks indicate significantly differences (p < 0.05) compared to the controls lacking inhibitors.

Mercury Accumulation and Elimination: Why Is Organic Mercury Not Removed?

The major question raised by our results is why the efflux transporters are less effective at removal of organic mercury as opposed to inorganic mercury. Since glutathione is an abundant –SH donor in sea urchins we would expect some fraction of intracellular organic mercury to have associated with GSH and then been expelled by MRP. One explanation for these results could be differences in the rate of formation of the organic mercury–GSH complex as opposed to spontaneous binding of organic mercury to sulfhydryl groups on intracellular proteins. We observed that CDNB and EA did not significantly increase the potency of organic mercury, indicating either little catalysis of mercury binding to GSH by GST and/or a reduced spontaneous reaction with GSH, as compared to inorganic mercury. Since metals appear to be transported by MRP as GSH conjugates, reduced conjugation of organic mercury to GSH could underlie its enhanced accumulation. Similarly conjugation differences could underlie differences in potency increasing the availability of “free” organic mercury for binding to cysteine groups on major proteins such as tubulin, which comprises 5% of the soluble protein in the sea urchin egg (41). This would be consistent with our results indicating that the microtubules were apparent targets of mercuric compounds (Figures 1 and S1).

The increase in potency of inorganic mercury in the presence of only MK571 indicates that, although conjugation provides some protection, it is insufficient protection to ameliorate the cell cycle toxicity of mercury. As mentioned above, one possibility is that the fraction of mercury bound to an appropriate carrier for efflux transport is limited by competition with spontaneous binding to intracellular –SH groups (Figure S3; (42)). In this scenario, GST could play a role in rapidly shifting the balance of binding toward GSH, particularly at low environmental concentrations of these compounds. Differences in handing of the two compounds by GST could also underlie the differences we observed in potency and accumulation. Another study has suggested a role for GST in catalyzing inorganic mercury binding to GSH, showing that inorganic mercury can significantly induce GST activity (43). However, those GST effects occurred at higher inorganic mercury concentrations than those used in our study (3–30 µM) and they were not compared to effects of organic mercury on GST, indicating that these could possibly be indirect effects of the mercury exposure.

Additional evidence pointing to different handling of organic and inorganic mercury conjugates by efflux transporters comes from work in mammals (36), where both can bind to GSH, but the organic form nonetheless has a much longer half-life in the body (20, 21, 44). Both organic and inorganic mercury can be excreted more rapidly, presumably by MRP2, if animals are administered large amounts of exogenous sulfhydryl containing compounds (38), such as N-acteylcysteine (NAC), dimercaptopropane sulfonic acid (DMPS), or dimercaptosuccinnic acid (DMSA) (20, 21). These studies generally indicate that organic mercury conjugates are less effectively removed than the inorganic counterparts. For example, 80% of a renal load of inorganic mercury is eliminated from the kidney by MRP2 within 2 days as compared to 45% of an organic mercury dose. In addition, not all of the inorganic conjugates appear to be eliminated by the same transporters; so while 80% of a renal load of inorganic mercury is eliminated by DMPS, only half of this amount appears eliminated by the MRP2-dependent mechanism and the remainder is excreted by some as yet unknown mechanism. This may indicate that several different multidrug transporters are involved in efflux, each with differing affinity for the different conjugates.

Similar differences in the handling of respective endogenous organic and inorganic mercury conjugates, by several different efflux transporters, may play a role in the accumulation and potency differences we observed in sea urchins. Moreover, other transport systems such as OATs (45), or perhaps amino acid transporters (46, 47), could mediate mercury-conjugate uptake into marine animal cells as seen in polarized mammalian cells where mercury moves in a vectorial fashion across multiple cell surfaces. However, as relates to our study, all of the active transporters are presumably on the same surface of the embryo and thus these observed differences in mercury accumulation are most likely to result from differences in net efflux.

In the context of understanding environmental persistence of mercury in marine animals, this study points to the differential handling of mercury by MRP-like transporters as one mechanism for the paradoxical persistence of organic forms. Since “steady-state” efflux rates of mercuric compounds can be slow (48) once they have entered cells and bound to intracellular ligands that are not effluxed (e.g., proteins), the transporters and conjugating mechanisms may be most significant in mediating differences in the initial accumulation and partitioning of the two forms of mercury. In turn, these could lead to differences in trophic transfer of organic and inorganic mercury in marine food webs. For instance, Mason and colleagues (4) observed that organic mercury was assimilated more efficiently by copepods fed diatoms loaded with organic mercury, rather than inorganic mercury, and postulated that this was a consequence of partitioning of inorganic mercury into a cellular fraction of the diatoms that was excreted by copepods. Transport and conjugation could underlie these sorts of differences in mercury assimilation through combined effects on partitioning of mercury in prey and metabolism of mercury by predators. In addition, given the conservation of function for MRP in mercury homeostasis in deuterostomes as divergent as sea urchins and mammals, it also seems tenable that MRP could contribute to differences in assimilation of organic and inorganic mercury at higher trophic levels, including the mercury-contaminated fish species consumed by humans.

Finally, of interest is the question of “real-world” efficacy of efflux transport in preventing inorganic mercury accumulation and whether this is limited by persistent environmental contaminants that interfere with the transporters (7), such as nitromusks or perfluorocarbons. Marine organisms are continuously exposed to low levels of mercury and small alterations in the basal rates of accumulation, caused by transporter inhibitors, could have profound effects on lifetime burdens and net movement of mercury through trophic levels. This study underscores how a working knowledge of the behavior of key cellular defenses, and of their susceptibility to real-world perturbations, would give insight into future levels of mercury in marine organisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mark Hahn and Heather Coleman for critical reading of the manuscript and Dr. Ned Ballatori for his comments on the work. This research was supported by NIH Grants HD47316 and HD050870 to A.H., NSF Grant 044834 to D.E., and Grants from the Ministry of Science, Education and Sports of Republic of Croatia Project 058-0582261-2246 to J.F.C. and 098-0982934-2745 to T.S.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Figure S1: Analysis of mercury effects during the first cell division of sea urchin embryos; Figure S2: Effects of different ABC transporter inhibitors on potency of mercury; Figure S3: Calcein-am accumulation in 2-cell embryos treated with mercury. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

Literature Cited

- 1.Mackay D. Correlation of bioconcentration factors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1982;16:274–278. doi: 10.1021/es00099a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neely WB, Branson DR, Blau GE. Partition coefficient to measure bioconcentration potential of organic chemicals in fish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1974;8:1113–1115. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swackhamer DL, Skoglund RS. Bioaccumulation of PCBs by algae: kinetics versus equilibrium. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1993;12:831–838. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mason RP, Reinfelder JR, Morel FMM. Uptake, Toxicity and Trophic Transfer of Mercury in a Coastal Diatom. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1996;30:1835–1845. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morel FMM, Kraepiel AML, Amyot M. The chemical cycle and bioaccumulation of mercury. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1998;29:543–566. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conaway CH, Squire S, Mason RP, Flegal AR. Mercury speciation in San Francisco Bay estuary. Mar. Chem. 2003;80:199–225. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epel D, Luckenbach T, Stevenson CN, MacManus-Spencer LA, Hamdoun A, Smital T. Efflux Transporters: Newly Appreciated Roles in Protection against Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:3914–3920. doi: 10.1021/es087187v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean M, Rzhetsky A, Allikmets R. The Human ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporter Superfamily. Genome Res. 2001;11:1156–1166. doi: 10.1101/gr.184901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leslie EM, Deeley RG, Cole SPC. Toxicological relevance of the multidrug resistance protein 1, MRP1 (ABCC1) and related transporters. Toxicology. 2001;167:3–23. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00454-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbott NJ, Romero IA. Transporting therapeutics across the blood-brain barrier. Mol. Med. Today. 1996;2:106–113. doi: 10.1016/1357-4310(96)88720-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luckenbach T, Epel D. Nitromusk and polycyclic musk compounds as long-term inhibitors of cellular defense systems mediated by multidrug transporters. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113:17–24. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamdoun AM, Cherr GN, Roepke TA, Epel D. Activation of multidrug efflux transporter activity at fertilization in sea urchin embryos (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) Dev. Biol. 2004;276:452–462. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambdukar SV, Dey S, Hrycyna CA, Ramachandra M, Pastan I, Gottesman MM. Biochemical, Cellular and Pharmacological Aspects of the Multidrug Transporter. Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1999;39:361–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole SPC, Deeley G. Transport of glutathione and glutathione conjugates by MRP1. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2006;27:438–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballatori N, Hammond CL, Cunningham JB, Krance SM, Marchan R. Molecular mechanisms of reduced glutathione transport: role of the MRP/CFTR/ABCC and OATP/SLC21A families of membrane proteins. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005;201:238–255. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li ZS, Szczypka M, Lu YP, Thiele DJ, Rea PA. The Yeast Cadmium Factor Protein (YCF1) Is a Vacuolar Glutathione S-Conjugate Pump. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:6509–6517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein M, Burla B, Martinoia E. The multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP/ABCC) subfamily of ATP-binding cassette transporters in plants. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1112–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broeks A, Gerrard B, Allikmets L, Dean M, Plasterk RHA. Homologues of the human multidrug resistance genes MRP and MDR contribute to heavy metal resistance in the soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 1996;15:6132–6143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller DS, Shaw JR, Stanton CR, Barnaby R, Karlson KH, Hamilton JW, Stanton BA. MRP2 and Acquired Tolerance to Inorganic Arsenic in the Kidney of Killifish (Fundulus heteroclitus) Toxicol. Sci. 2007;97:103–110. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bridges CC, Joshee L, Zalups RK. MRP2 and the DMPS- and DMSA-Mediated Elimination of Mercury in TR- and Control Rats Exposed to Thiol S-Conjugates of Inorganic Mercury. Toxicol. Sci. 2008;105:211–220. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zalpus RK, Bridges CC. MRP2 involvement in renal proximal tubular elimination of methylmercury mediated by DMPS or DMSA. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009;235:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sea Urchin Genome Sequencing Consortium. The Genome of the Sea Urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Science. 2006;314:941–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1133609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstone JV, Hamdoun A, Cole BJ, Howard-Ashby M, Nebert DW, Scally M, Dean M, Epel D, Hahn ME, Stegeman JJ. The chemical defensome: Environmental sensing and response genes in the Strongylocentrotus purpuratus genome. Dev. Biol. 2006;300:366–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner E, Klevit R, Hager LJ, Shapiro BM. Ovothiols, a family of redox-active mercaptohistidine compounds from marine invertebrate eggs. Biochemistry. 1987;26:4028–4036. doi: 10.1021/bi00387a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shapiro BM. The control of oxidant stress at fertilization. Science. 1991;252:533–536. doi: 10.1126/science.1850548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foltz KR, Adams NL, Runft LL. Echinoderm eggs and embryos: procurement and culture. In: Wilson L, Matsudaira P, editors. Methods in Cell Biology. Vol. 74. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. pp. 39–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. www.epa.gov/osw/hazard/testmethods/sw846/pdfs/7473.pdf.

- 28.von Dassow G, Foe V. Simultaneous Fixation and Visualization of the Actin and Microtubule Cytoskeletons. In: Wilson L, Matsudaira P, editors. Methods in Cell Biology. Vol. 74. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. pp. 385–393. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yole M, Wickstrom M, Blakley B. Cell death and cytotoxic effects in YAC-1 lymphoma cells following exposure to various forms of mercury. Toxicology. 2007;231:40–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogel DG, Margolis RL, Mottet NK. The effects of methyl mercury binding to microtubules. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1985;80:473–486. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(85)90392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ochi T. Methylmercury, but not inorganic mercury, causes abnormality of centrosome integrity (multiple foci of γ-tubulin), multipolar spindles and multinucleated cells without microtubule disruption in cultured Chinese hamster V79 cells. Toxicology. 2002;175:111–121. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller DS. Nucleoside phosphonate interactions with multiple organic anion transporters in renal proximal tubule. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001;299:567–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holló Z, Homolya L, Hegedüs T, Sarkadi B. Transport properties of the multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) in human tumour cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;383:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keppler D, Jedlitschky G, Leier I. Transport function and substrate specificity of multidrug resistance protein. Methods Enzymol. 1998;292:607–616. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)92047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Essodaigui M, Broxterman HJ, Garnier-Suillerot A. Kineticanalysis of calcein and calcein-acetoxymethyl ester efflux mediated by the multidrug resistance protein and P-glycoprotein. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2243–2250. doi: 10.1021/bi9718043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ballatori N, Clarkson TW. Biliary Secretion of Glutathione and Glutathione-Metal Complexes. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1985;5:816–831. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(85)90165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishikawa T, Bao J-J, Yamane Y, Akimaru K, Frindrich K, Wright CD, Kuo MT. Coordinated Induction of MRP/GS-X Pump and γ-Glutamylcysteine Synthetase by Heavy Metals in Human Leukemia Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:14981–14988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR. Glutathione transferases. Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005;45:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salinas AE, Wong MG. Glutathione S-Transferases - A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 1999;6:279–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zaman GJR, Lankelma J, van Tellingen O, Beijnen J, Dekker H, Paulusma C, Oude Elferink RPJ, Baas F, Borst P. Role of glutathione in the export of compounds from cells by the multidrug-resistance-associated protein. Med. Sci. 1995;92:7690–7694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfeffer TA, Asnes CF, Wilson L. Properties of Tubulin in Unfertilized Sea Urchin Eggs. Quantitation and Characterization by the Colchicine-Binding Reaction. J. Cell Biol. 1976;69:599–607. doi: 10.1083/jcb.69.3.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim SH, Bark H, Choi CH. Mercury induces multidrug resistance-associated protein gene through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Toxicol. Lett. 2005;155:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aleo MF, Morandini F, Bettoni F, Giuliani R, Rovetta F, Steimberg N, Apostoli P, Parrinello G, Mazzoleni G. Endogenous thiols and MRP transporters contribute to Hg2+ efflux in HgCl2-treated tubular MDCK cells. Toxicology. 2005;206:137–151. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clarkson TW, Magos L, Myers GJ. The Toxicology of Mercury - Current Exposures and Clinical Manifestations. New Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:1731–1737. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aslamkhan AG, Han Y-H, Yang X-P, Zalups RK, Pritchard JB. Human Renal Organic Anion Transporter 1-Dependent Uptake and Toxicity of Mercuric-Thiol Conjugates in Madin-Darby Canine Kidney Cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;63:590–596. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.3.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kerper LE, Ballatori N, Clarkson TW. Methylmercury transport across the blood-brain barrier by an amino acid carrier. Am. J. Physiol. - Reg., Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1992;262:R761–R765. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.5.R761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bridges CC, Zalups RK. Molecular and ionic mimicry and the transport of toxic metals. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005;204:274–308. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fowler SW, Heyraud M, La Rosa J. Factors affecting methyl and inorganic mercury dynamics in mussels and shrimp. Mar. Biol. 1978;46:267–276. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.